Thursday Nov. 9, 2006

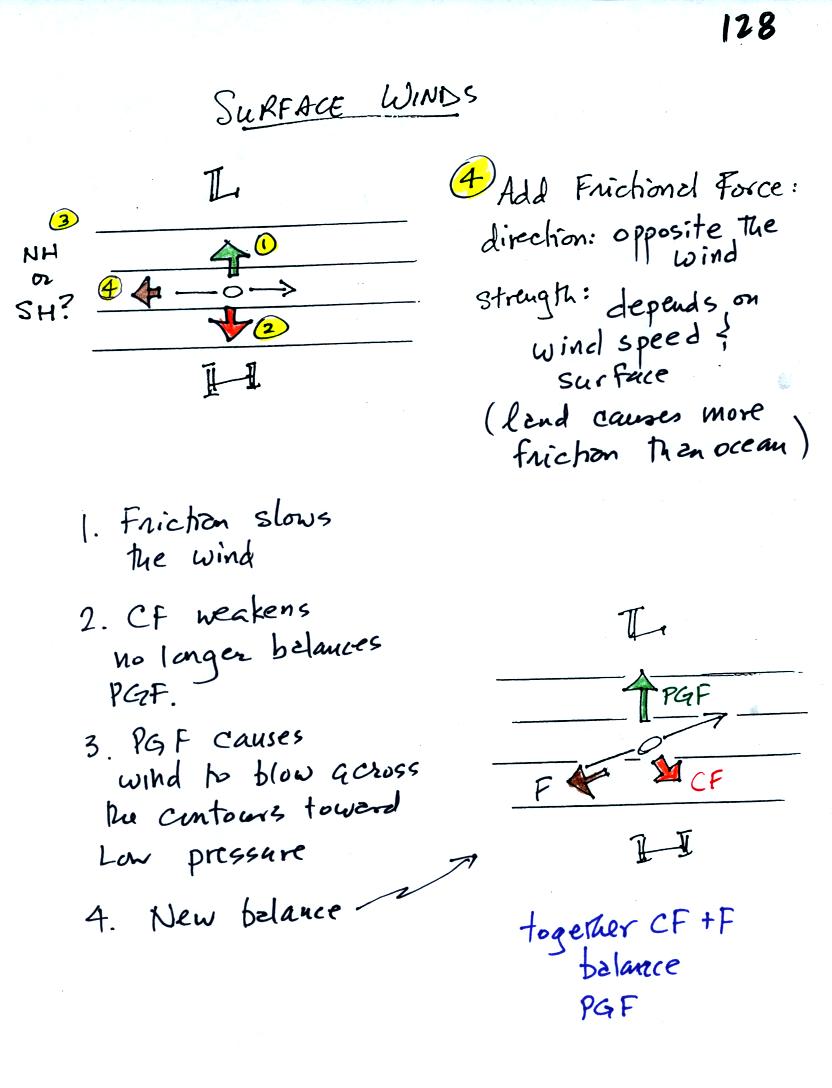

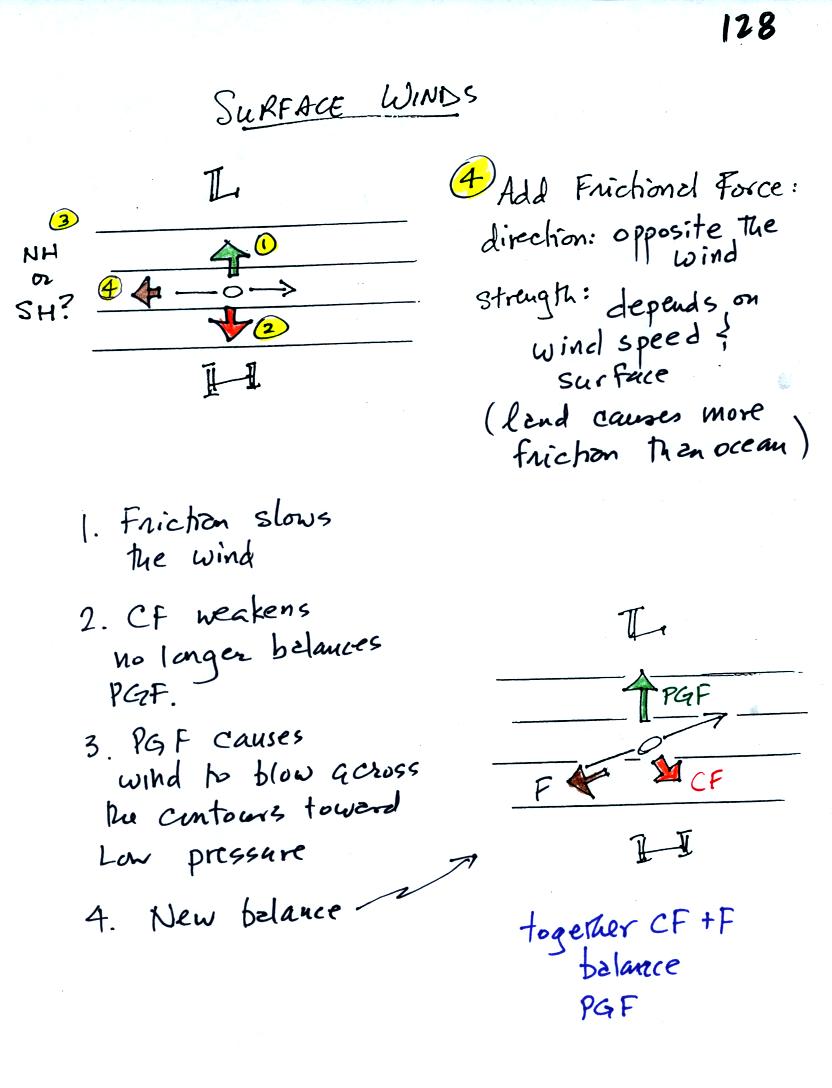

Now we'll look briefly at surface winds. We must now include the

frictional force.

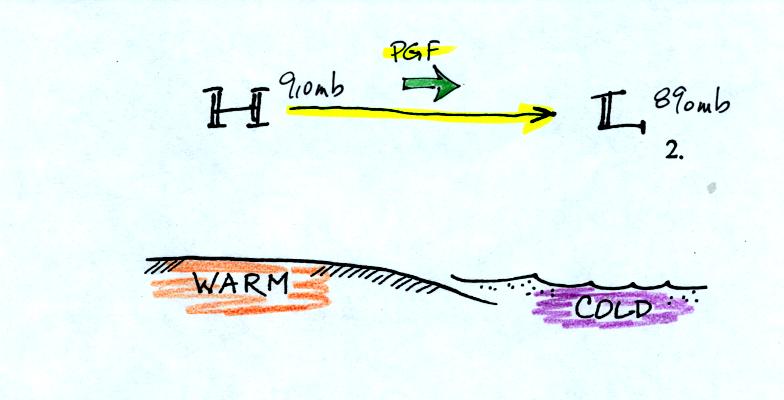

In the figure at top left, we start at Point 1 by drawing in the

pressure gradient force (perpendicular to the contour lines and

pointing toward low pressure). Then we can draw in an equal and

oppositely directed CF so that the net force will be zero. Since

the CF is the right of the wind we can say this is a NH chart.

The frictional force will always point in a direction opposite the

wind. Friction always try to slow moving objects (it doesn't

cause you to speed up on your bicycle or to veer suddenly to the right

or left). The strength of the frictional force depends on wind

speed (stronger when the winds are fast and zero when the wind isn't

blowing at all). Friction also depends on the type of surface the

wind is blowing over.

The friction will slow the wind. That in turn weakens the CF

(remember the strength of the CF depends on wind speed. The CF no

longer balances the PGF, and the wind turns slightly and blows across

the contours toward low pressure. On a chart like this with

straight contours you end up with a new balance among the forces.

Together the CF + F = PGF. The wind will blow in a straight line

at constant speed across the contours toward low pressure.

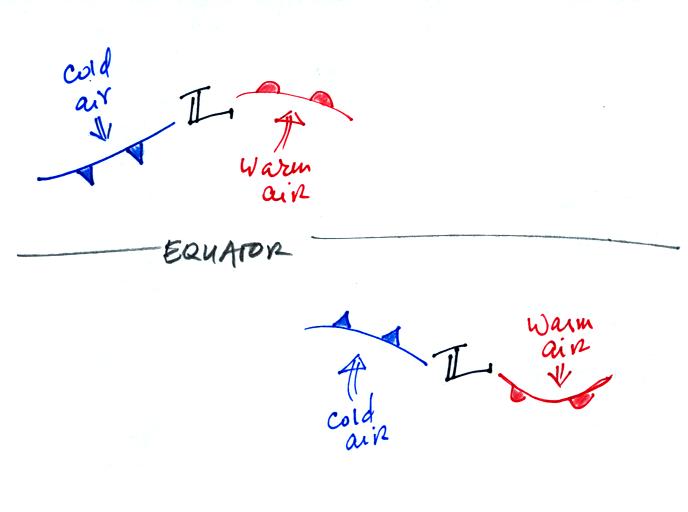

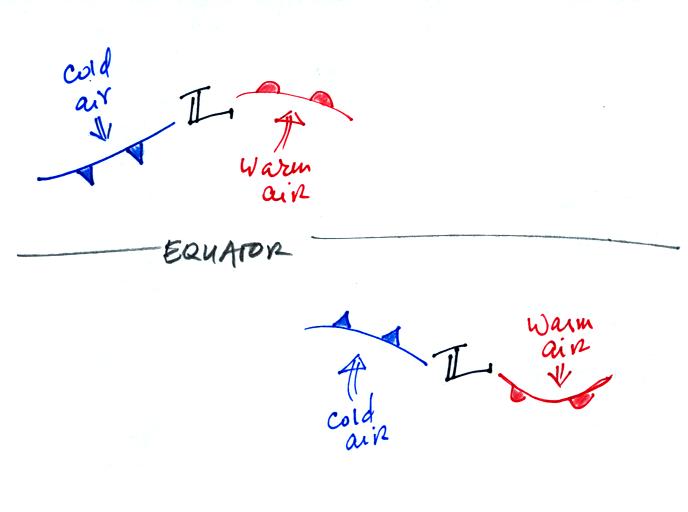

This figure compares middle latitude storms in the NH and SH. In

the NH cold air moves southward from higher latitudes on the west side

of the low, warm air moves northward on the east side. The fronts

spin counterclockwise around the low pressure center.

In the SH cold air moves northward, the cold air is found in the south,

again on the west side of the low. Warm air moves southward on

the east side of the low. The fronts rotate clockwise around the

low.

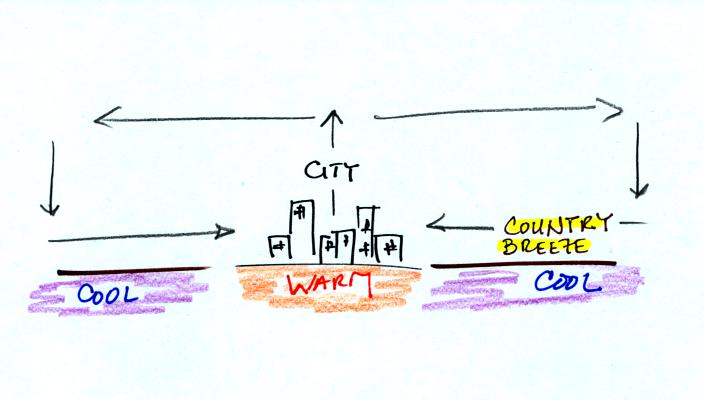

Differences in temperature such

as might develop between a coast and

the ocean or between a city and the surrounding country side can create

horizontal pressure differences. The horizontal pressure gradient can

then produce a wind flow pattern known as a thermal circulation.

These are generally relatively small scale circulations and the

pressure gradient is so much stronger than the Coriolis force that the

Coriolis force can be ignored. We will learn how thermal

circulations develop and then apply to concept to the earth as a

whole

in order to understand large global scale pressure and wind

patterns. What follows is a

slightly different version of what you will find on p. 131 in the

photocopied class notes.

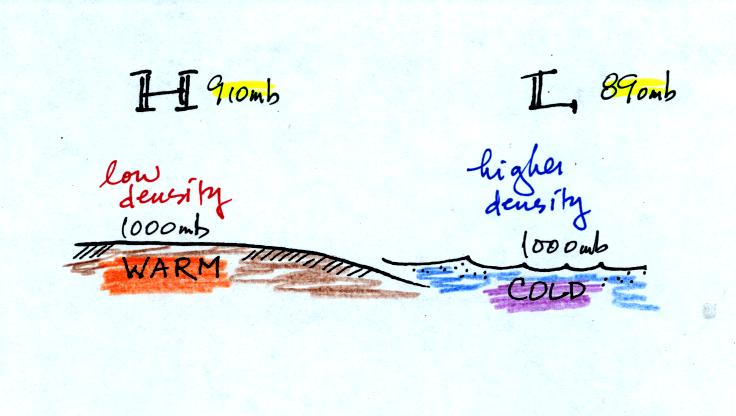

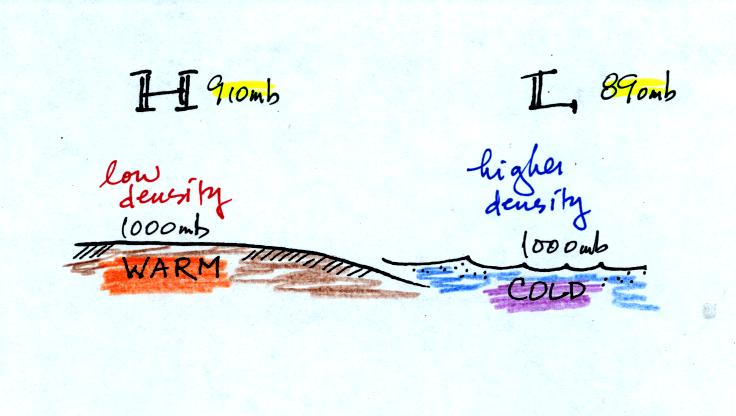

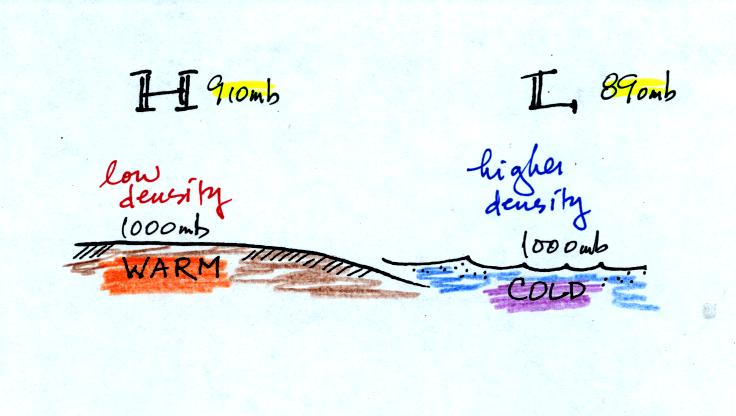

A beach will often become much warmer than the nearby

ocean during

the day (the sand gets hot enough that it is painful to walk across in

barefeet). Pressure will decrease more slowly with increasing

altitude in the warm low density

air than in the cold higher density

air above the ocean. Even when the sea level pressures are the

same over the land and water (1000 mb above) an upper level pressure

gradient can be created.

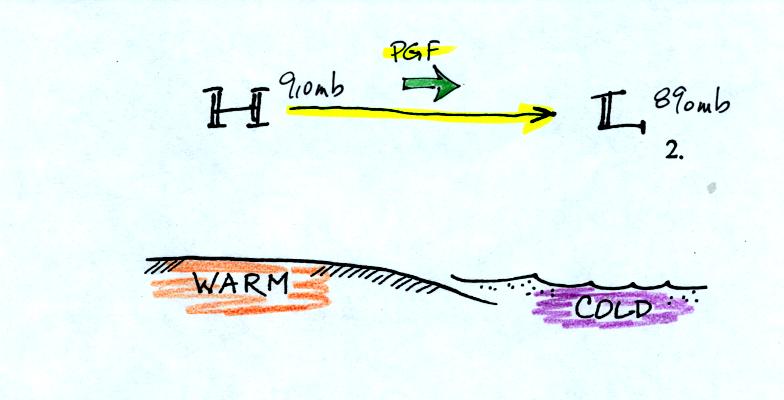

The upper level pressure gradient force will

cause upper level winds to

blow from H (910 mb) toward L (890 mb).

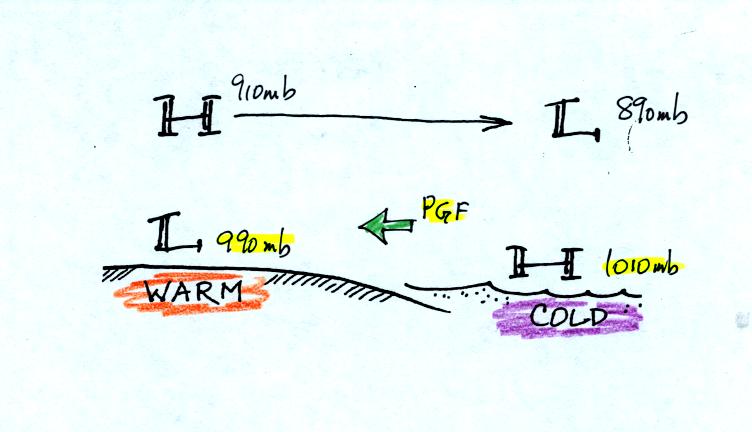

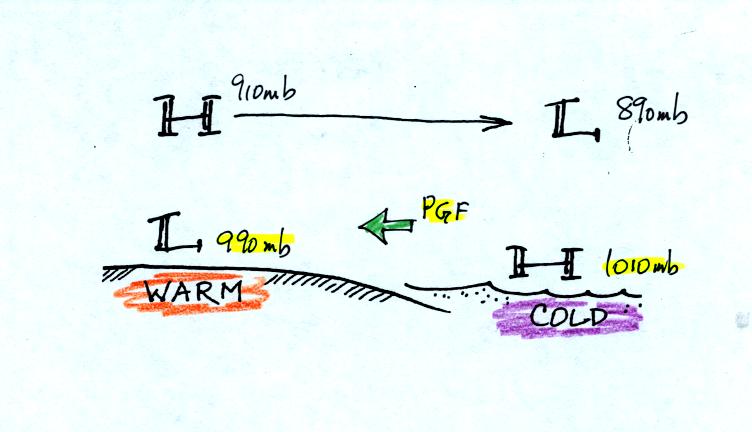

The movement of air above the ground can affect the surface

pressures. As air above the ground begins to move from left to

right, the surface pressure at left will decrease (from 1000 mb to 990

mb

in the picture above). Adding air at right will increase the

surface pressure there (from 1000 to 1010 mb). This creates a

surface

pressure gradient and surface winds begin to blow from right to left

(the opposite of what is going on above the ground).

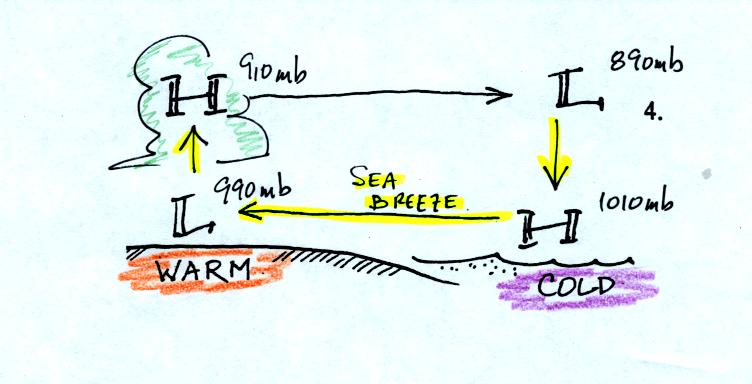

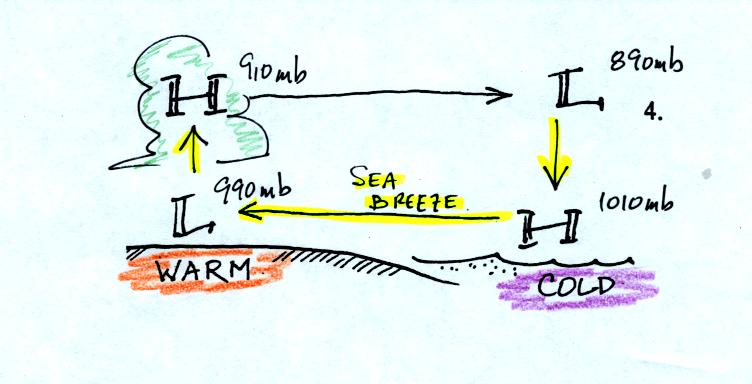

You can complete the picture by adding rising air above the

surface low

and sinking air above the surface high. Because the surface winds

come from the ocean they are referred

to as a sea breeze. These

winds would probably be pretty moist so clouds would be likely over

land above the surface low.

At some point during the night, the ocean often ends up warmer than the

land. The thermal circulation reverses direction. The

surface winds are then called a land breeze and clouds and rain form

out over the ocean.

Here are

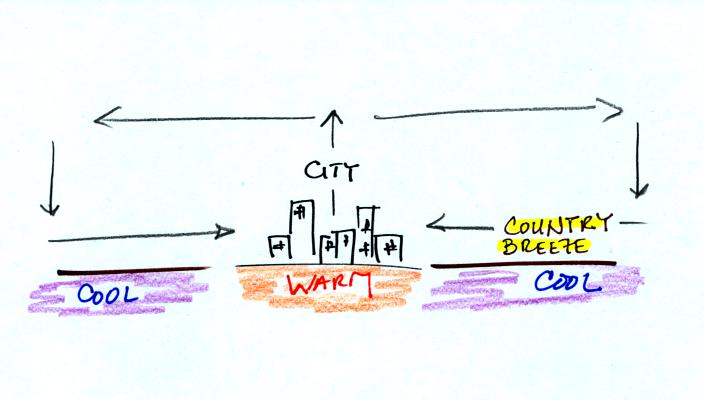

some thermal circulation like examples

Cities will sometimes become warmer than the surrounding

countryside,

especially at night. This difference in temperature can create a

"country breeze."

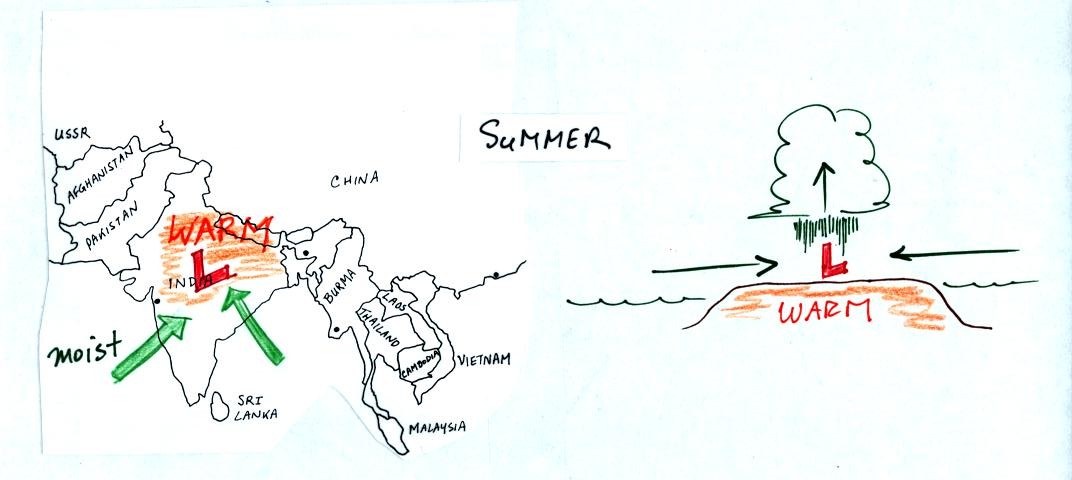

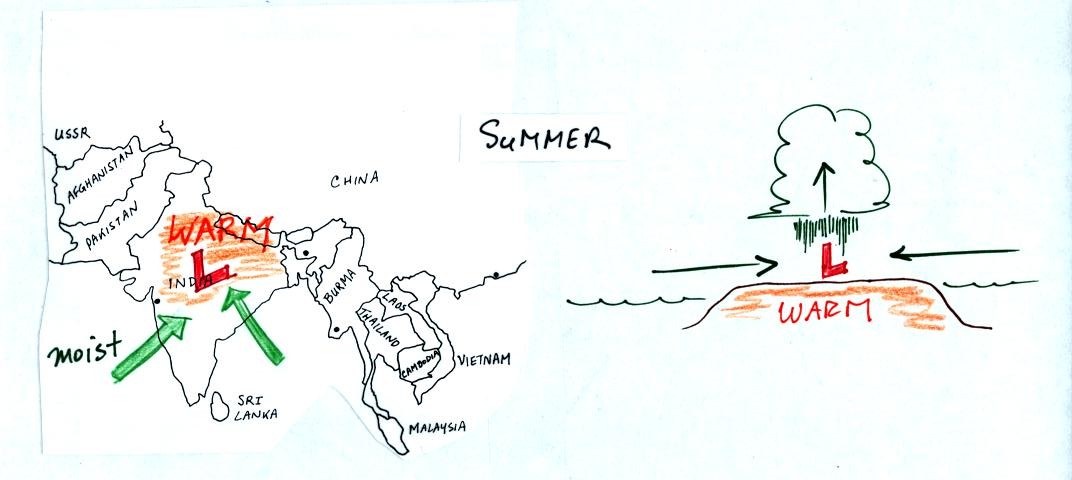

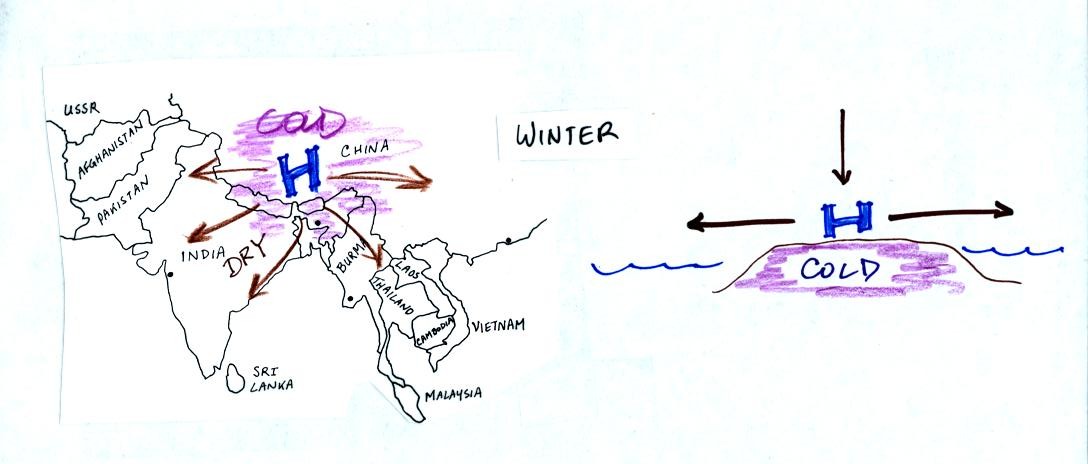

In the summer India and SE Asia become warmer than the

oceans

nearby. Surface low pressure forms over the land, moist winds

blow from the ocean onshore, and very large amounts of rain can

follow.

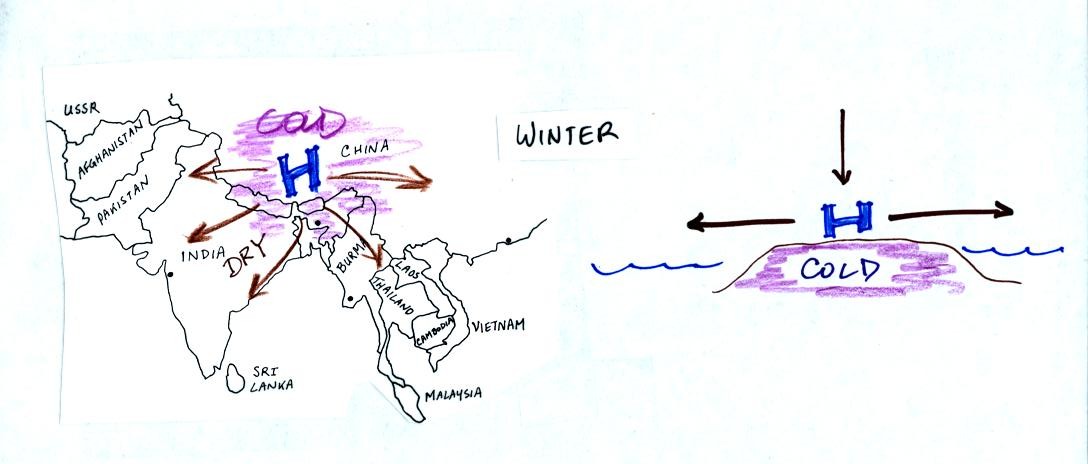

In the winter, high pressure forms over the land, and dry

winds blow

from land out over the ocean.

This is an example of a monsoon wind system, a situation where the

prevailing winds change directions with the seasons.

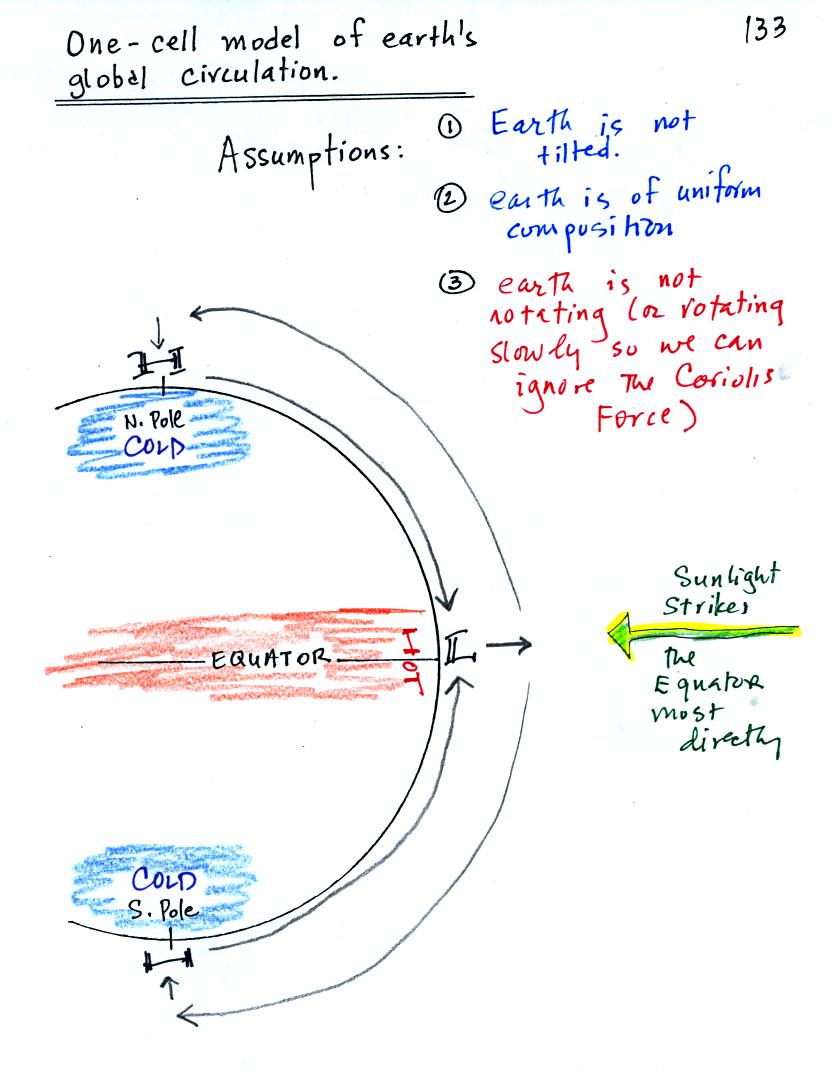

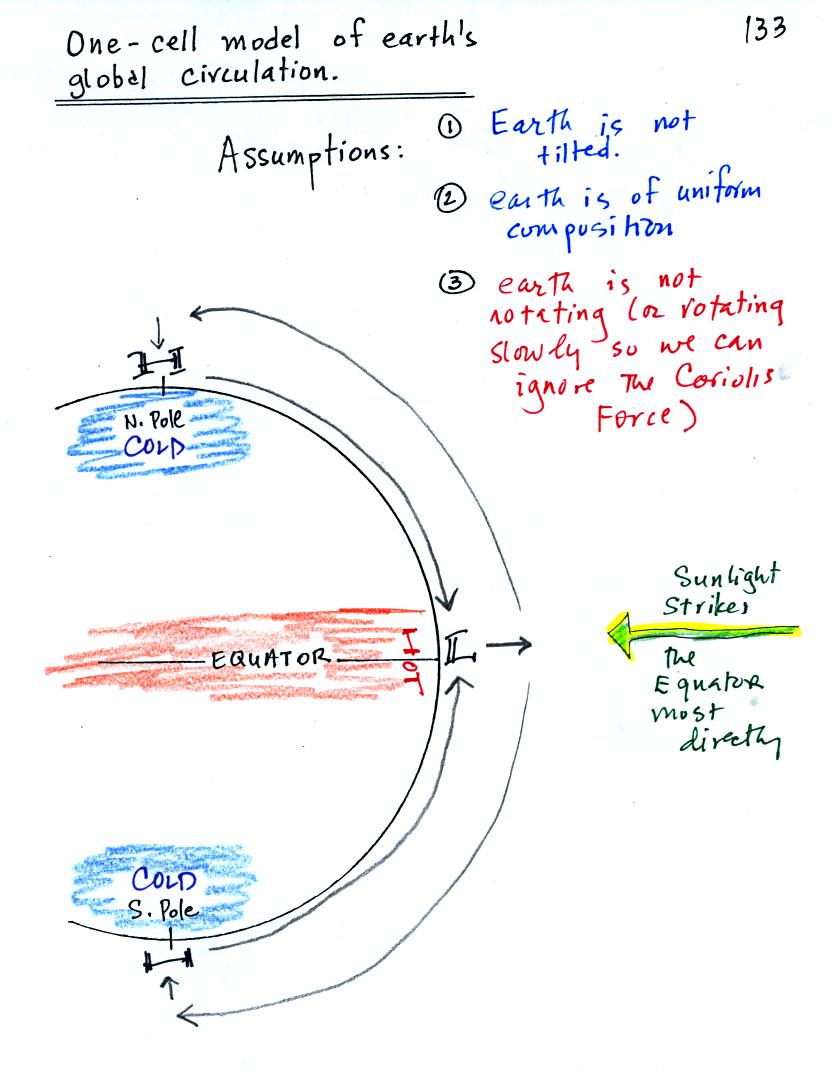

Now we'll

apply the thermal circulation concept to the earth as a whole and learn

about the "one-cell model" of the earth's global pressure and wind

circulation pattern. You'll learn what the "one-cell" refers to

shortly. A model is

just a simplified depiction or representation of the earth's global

scale circulation.

The incoming sunlight shines on the earth most directly at

the

equator. The equator will become hotter than the poles. By

allowing the earth to rotate slowly we spread this warmth out along the

entire length of the equator rather than concentrating it in a spot on

the side of the earth facing the sun.

You can see the wind

circulation pattern that would develop (really

just the same situation as the second sample problem studied

earlier). The term one cell just means there is one complete loop

in the northern hemisphere and another in the southern hemisphere.

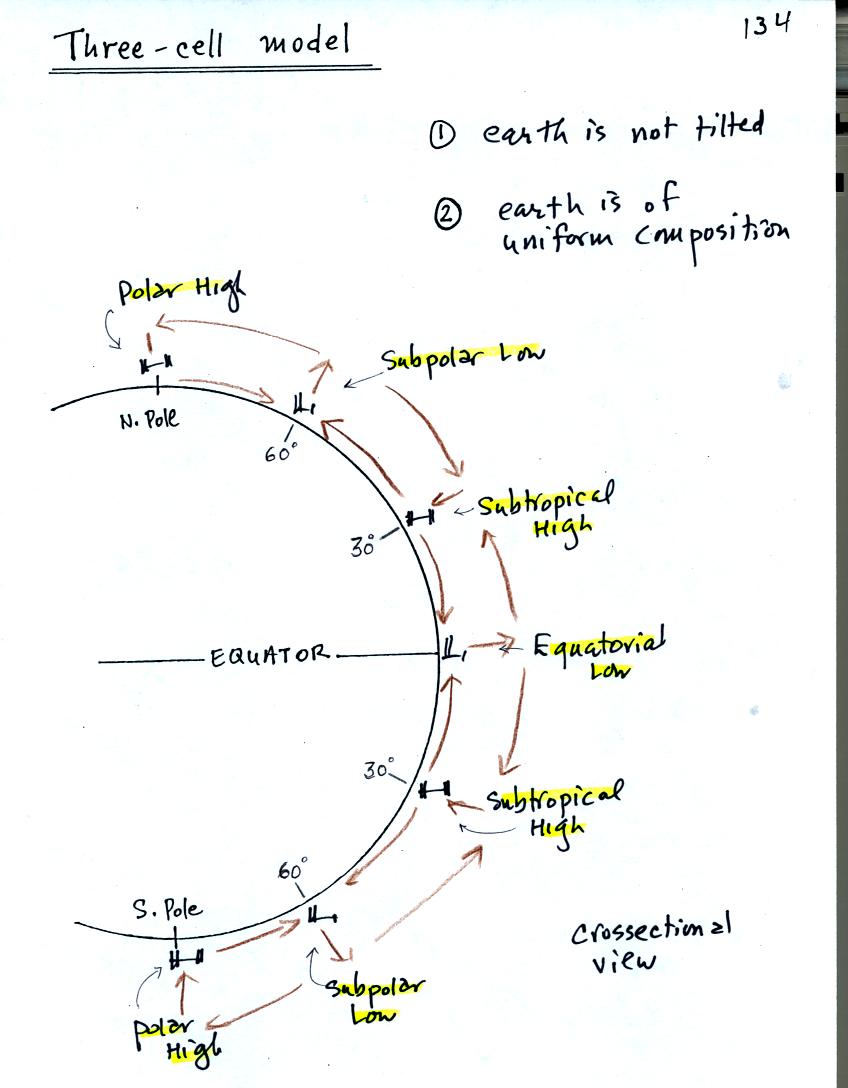

Next we will remove the assumption concerning the rotation of the

earth. We won't be able to ignore the Coriolis force now.

Here's what a computer would predict you would now see on

the earth. Things are pretty much the same at the equator in the

three cell and one cell models: low pressure and rising air. At

upper levels the winds begin to blow from the equator toward the

poles. Once headed toward the poles the upper

level winds are deflected by the Coriolis force.

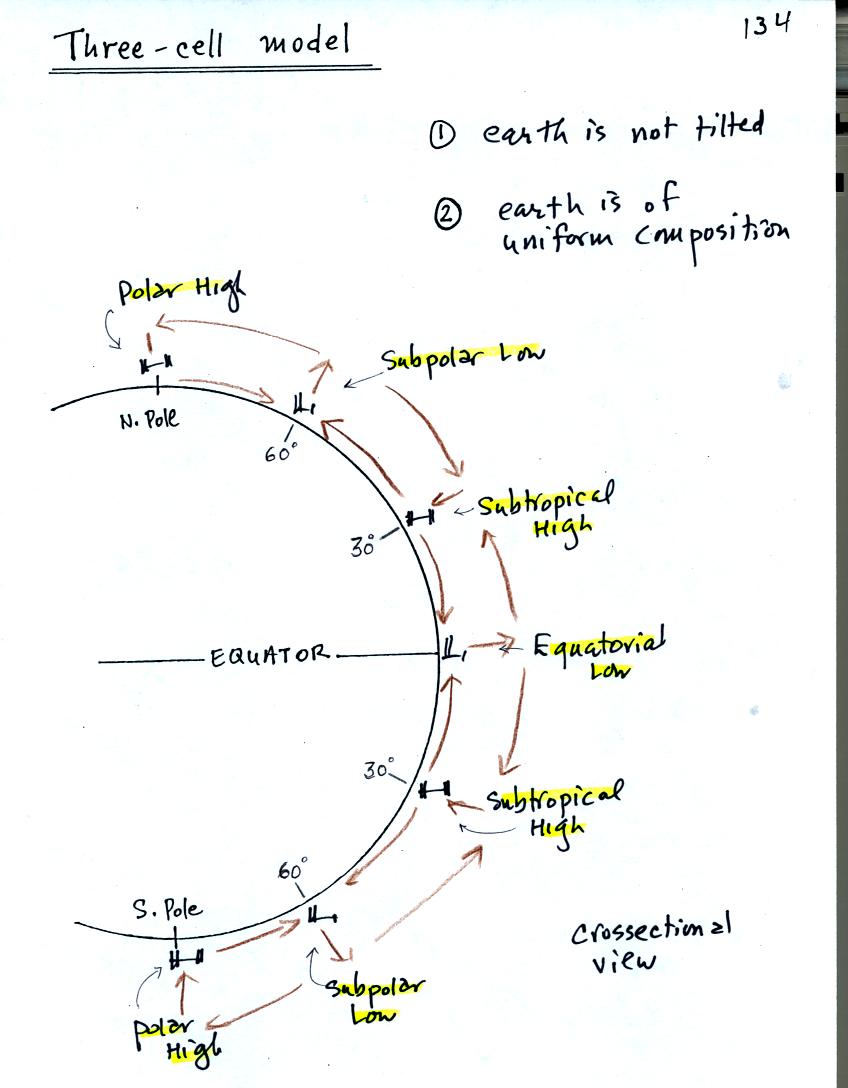

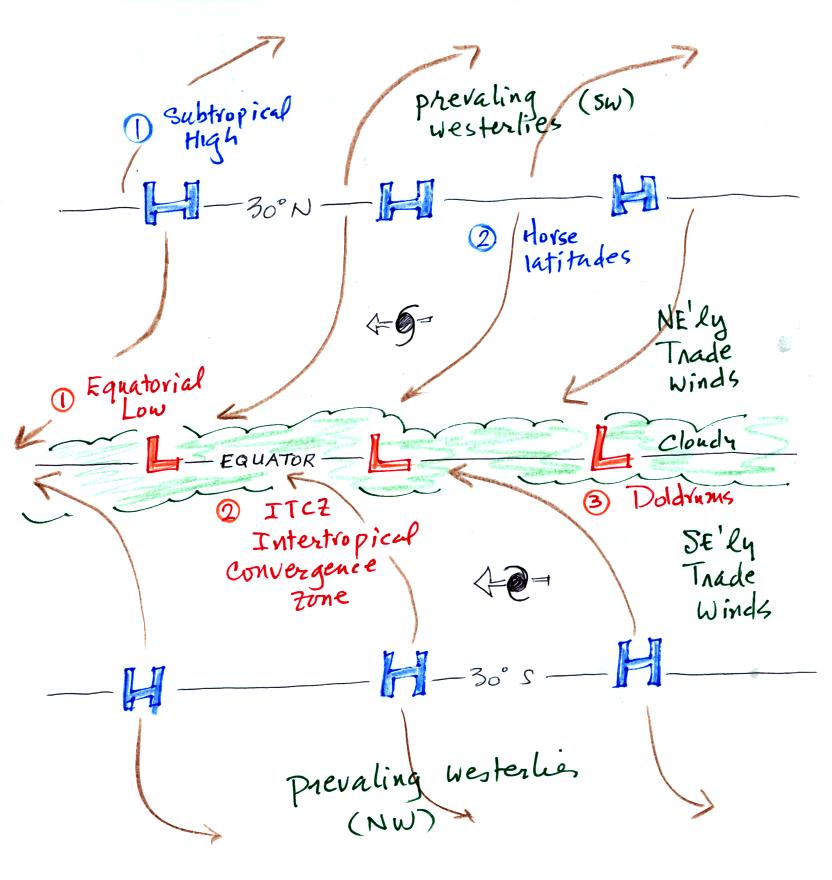

There end up being three closed loops in the northern and in the

southern hemispheres. There are belts of low pressure

at the equator (equatorial low)

and at 60 degrees latitude (subpolar

low). There are belts of high pressure (subtropical high) at 30

latitude and high pressure centers at the two poles (polar highs).

We will look at the surface features in a little more detail because

some of what is predicted, even with the unrealistic assumptions, is

actually found on the earth.

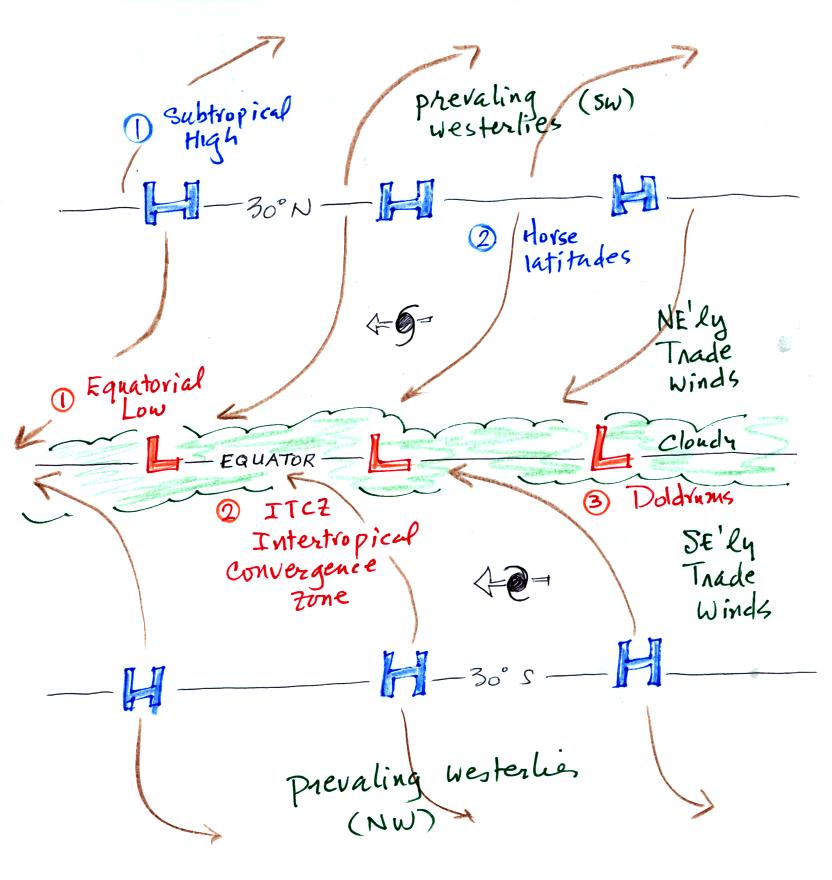

We'll first look at surface pressures and winds on the earth from 30 S

to 30 N.

Then we'll look at the region from 30 N to 60 N, where most of the

US is located.

This is the first map. Let's start at 30 S.

Winds will begin to

blow from High pressure at 30 S toward Low pressure at the

equator. Once the winds start to blow they will turn to the left

because of the Coriolis force. Winds blow from 30 N toward the

equator and turn to the right in the northern hemisphere (you need to

turn the page upside down and look in the direction the winds are

blowing). These are the Trade

Winds. They converge at the

equator and the air there rises (refer back to the crossectional view

of the 3-cell model). This is the cause of the band of clouds that you

can often see at or near the equator on a satellite photograph.

The Intertropical Convergence Zone or ITCZ is another name for the

equatorial low pressure belt. This region is

also referred to as the doldrums because it is a region where surface

winds are often weak. Sailing ships would sometimes get stranded

there hundreds of miles from land. Fortunately it is a

cloudy and

rainy region so the sailors wouldn't run out of drinking water.

Hurricanes form over warm ocean water in the subtropics between the

equator and 30

latitude. Winds at these latitudes have a strong easterly

component and hurricanes, at least early in their development, move

from east to west. Middle latitude storms found between 30 and 60

latitude, where the prevailing westerly

wind belt is found, move from

west to east.

You find sinking air, clear skies, and weak surface winds associated

with the subtropical high pressure belt. This is also known as

the horse latitudes. Sailing ships could become stranded there

also. Horses were apparently either thrown overboard (to conserve

drinking water) or eaten if food supplies were running low. Note

that sinking air is associated with the subtropical high pressure belt

so this is a region on the earth where skies are clear (Tucson is

located at 32 N latitude, so we are affected by the subtropical high

pressure belt).

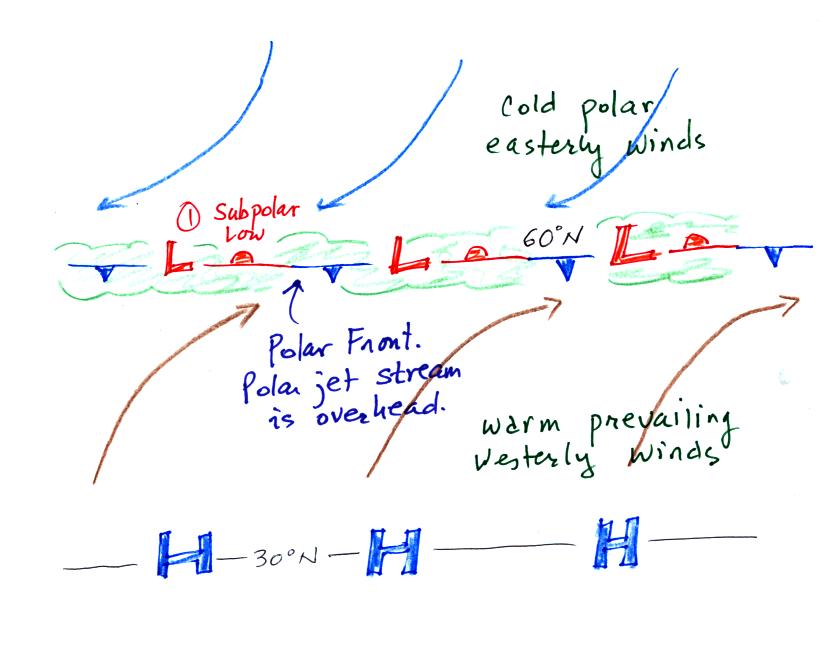

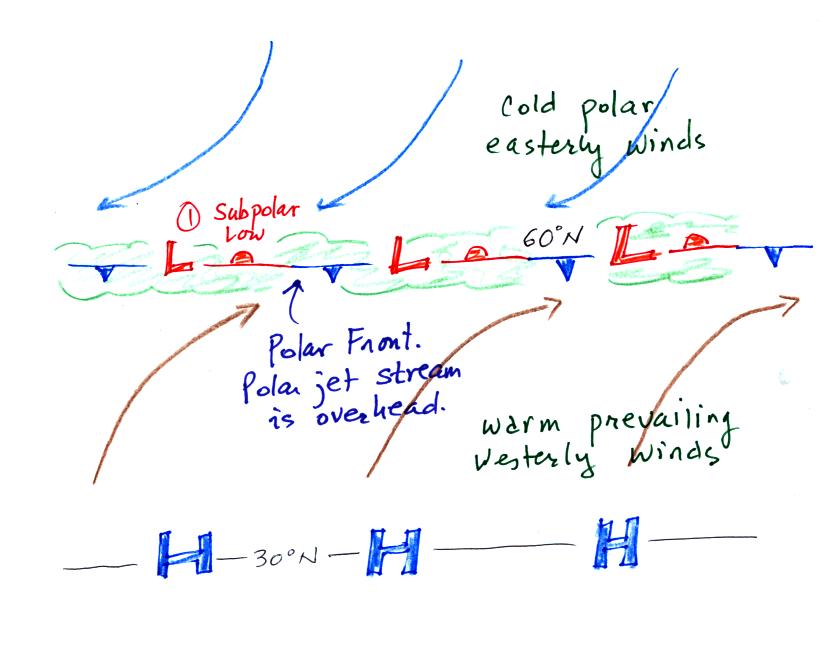

Here's the other map, it's a little simpler. Winds

blowing north from H

pressure at 30 N toward Low pressure at 60 N turn to the right and blow

from the SW. These are called the "prevailing westerlies."

In the southern hemisphere the prevailing westerlies blow from

the northwest. The 30 S to 60 S latitude belt in the southern

hemisphere is mostly ocean. The prevailing westerlies there can

get strong, especially in the winter. They are sometimes referred

to as the "roaring 40s" or the "ferocious 50s."

The subpolar low pressure belt is found at 60

latitude. Note this

is also a convergence zone where the cold polar easterly winds and the

warmer prevailing westerly winds meet. The boundary between these

two different kinds of air is called the polar front and is often drawn

as a stationary front on weather maps. A strong current of winds

called the polar jet stream is found overhead. Middle

latitude storms will often form along the polar front.

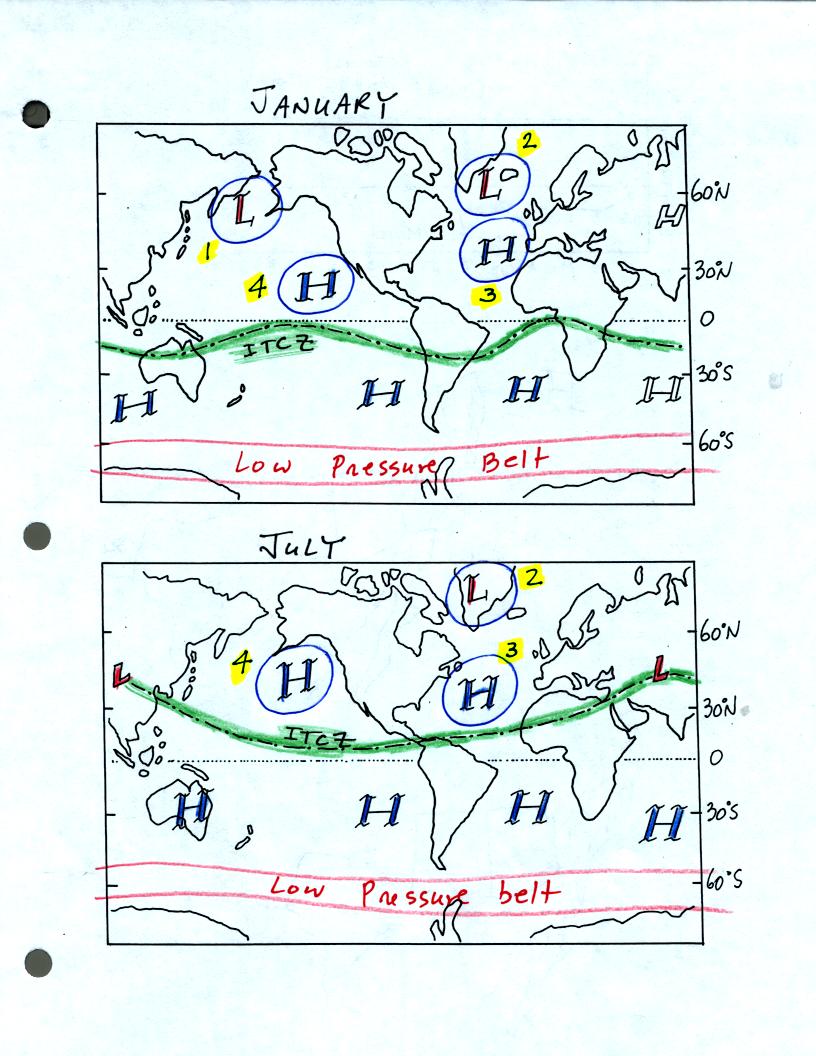

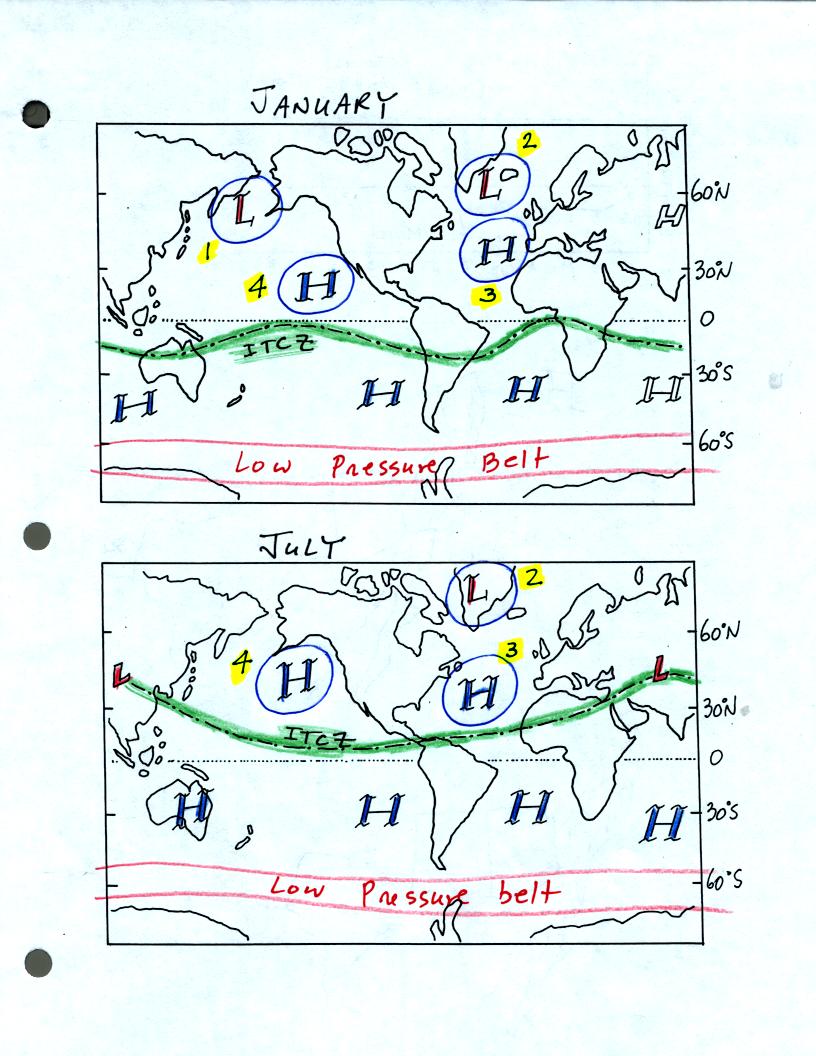

Despite

the simplifying assumptions in the 3-cell model, some of the features

that it predicts (particularly at the surface) are found in the real

world. This is illustrated in the

next figure.

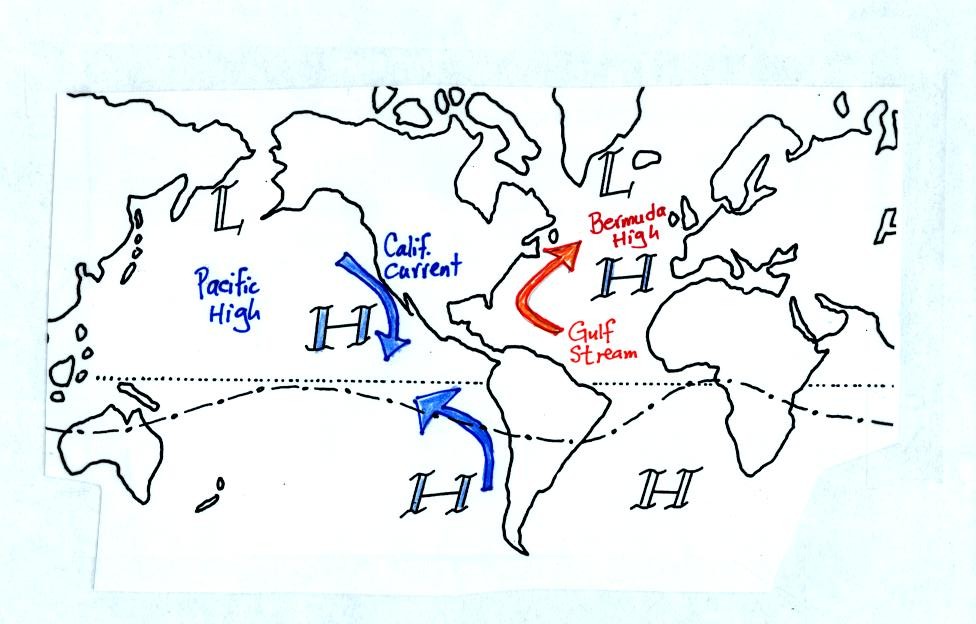

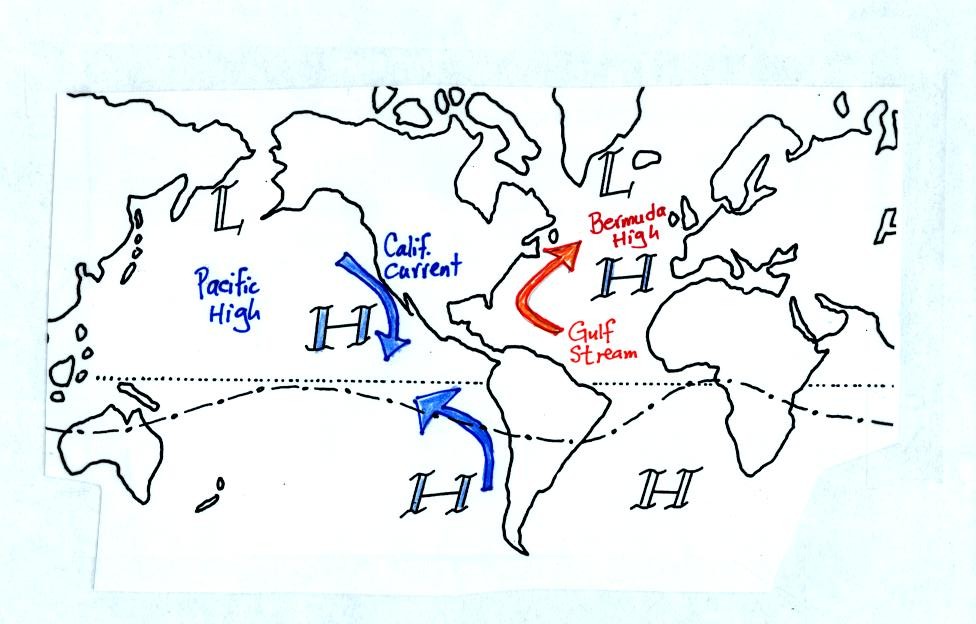

The 3-cell model predicts subtropical belts of high

pressure near

30

latitude. What we really find are large circular centers of high

pressure. In the northern hemisphere the Bermuda high is found

off the east coast of the US (feature 3 in the figure), the Pacific

high (feature 4) is positioned

off the

west coast. Circular low pressure centers, the Icelandic (feature

2) and

Aleutian low (feature 1), are found near 60 N. In the southern

hemisphere you

mostly just find ocean near 60 S latitude. In this part of the

globe the assumption of the earth being of uniform composition is

satisfied and a true subpolar low

pressure belt as predicted by the 3-cell model is found near 60 S

latitude.

The equatorial low or IRCZ is shown in green. Notice how it moves

north and south of the equator at different times of the year.

The winds that blow around these large scale high and low pressure

centers create the major ocean currents of the world. If you

remember that high pressure is positioned off the east and west coast

of the US, and that winds blow clockwise around high in the northern

hemisphere, you can determine the directions of the ocean currents

flowing off the east and west coasts of the US. The Gulf Stream

is a warm current that flows from south to north along the east coast,

the California current flows from north to south along the west coast

and is a cold current. A cold current is also found along the

west coast of South America (a disruption of this current often signals

the beginning of an El Nino event); winds blow counterclockwise around

high in

the southern hemisphere. These currents are shown in the enlargement

below.