| Differences |

Similarities |

Differences |

| Found at middle latitudes (30 to

60 latitude) Can form over land or water |

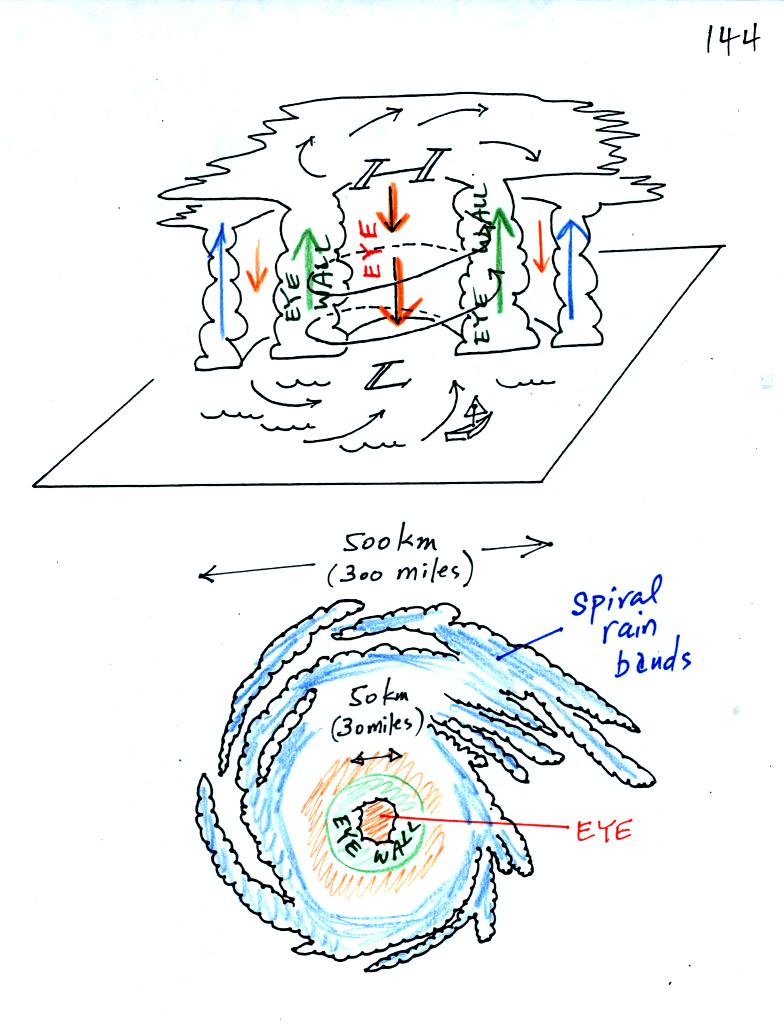

The term cyclone refers to winds

spinning around low pressure, both storms have low pressure centers (the low pressure becomes high pressure at the top of a hurricane) |

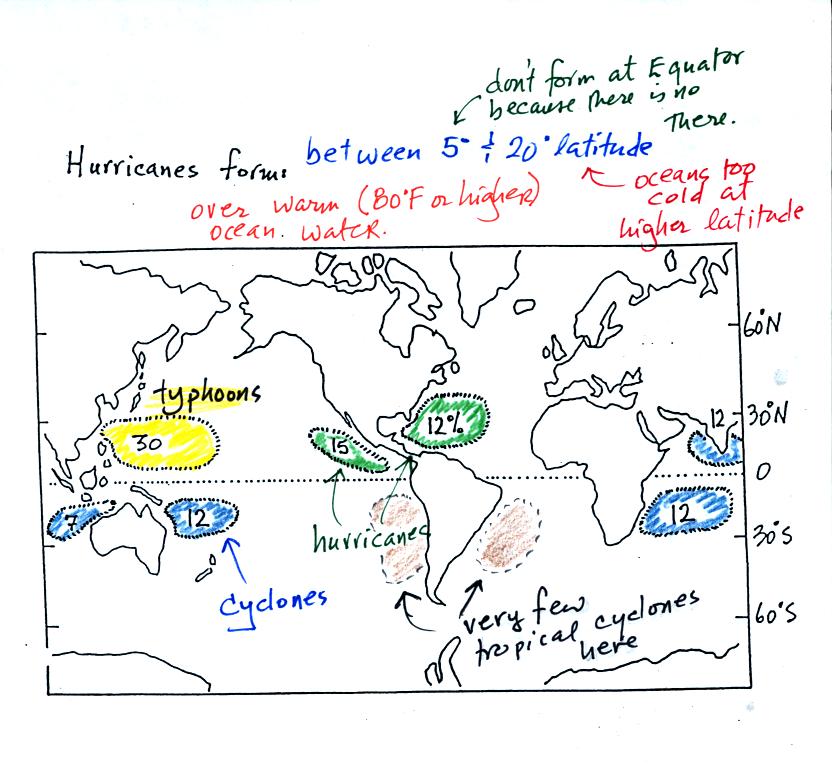

Found in the tropics (5 to 20

latitude) Only form over warm ocean water |

| Movement is from west to east | Upper level divergence cause

lower the surface pressure and cause both types of storms to intensity |

Movement is from east to west |

| Warm and cold air masses brought together by converging winds | Warm moist air mass only | |

| Storm winds intensify with

altitude |

Storm winds weaken with altitude |

|

| Strongest storms usually occur

in the winter |

Strongest storms in the last summer to early fall |