Tuesday Sept. 19, 2006

Quiz #1 this coming Thursday. About 40% of the question on

the quiz will come from the Practice

Quiz Study Guide & 60% from the Quiz

#1 Study Guide.

Reviews Tuesday afternoon (Harvill 318 4-5 pm) &

Wednesday

afternoon

(Harvill 302 4-5 pm)

The Optional Assignments have been graded (no mark on your paper means

you received full credit). Answers

Where is my graded 1S1P report?

Review

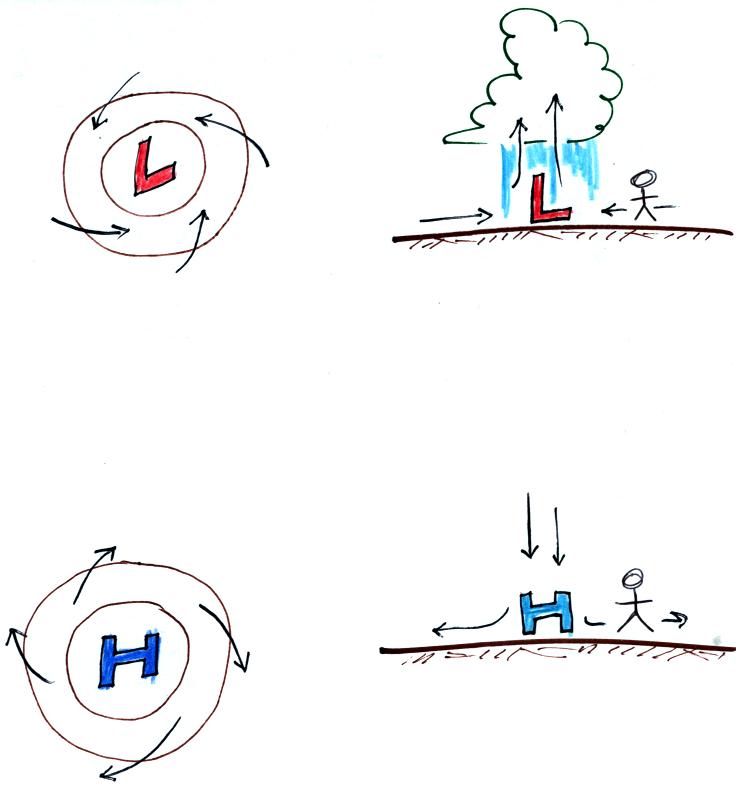

- What do high and low pressure centers on a surface weather map tell

you about the weather in their vicinity?

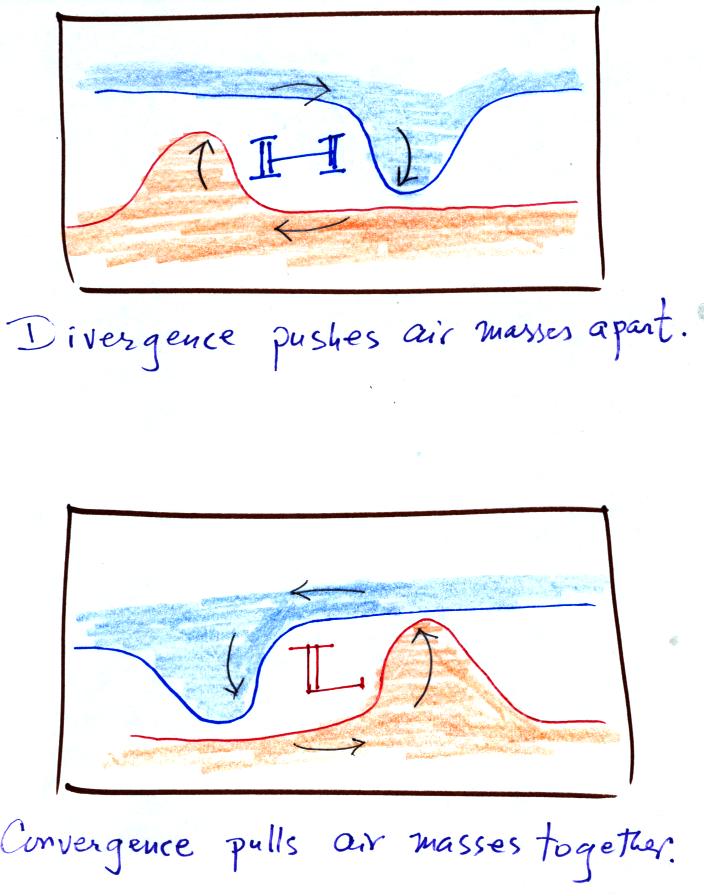

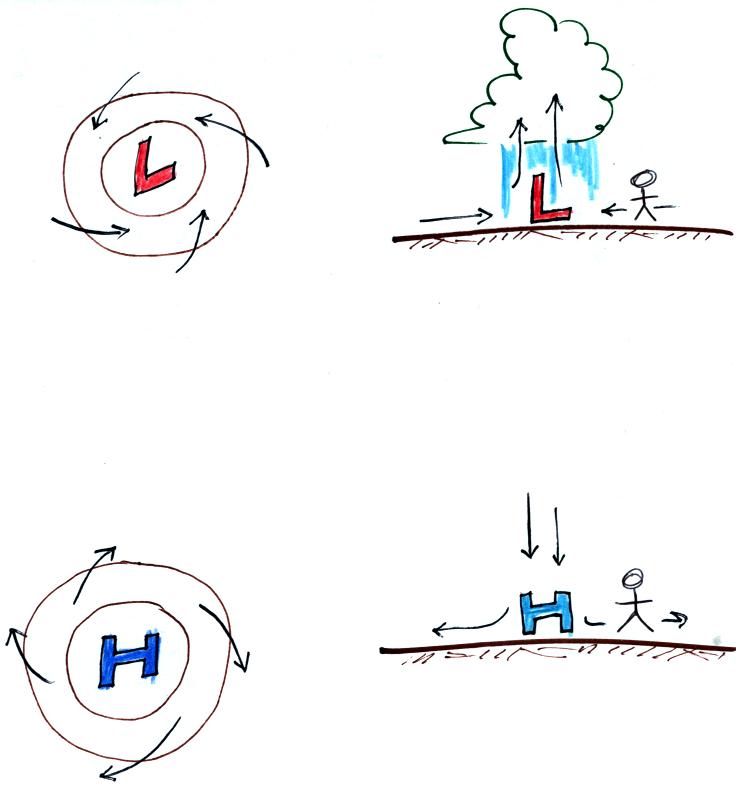

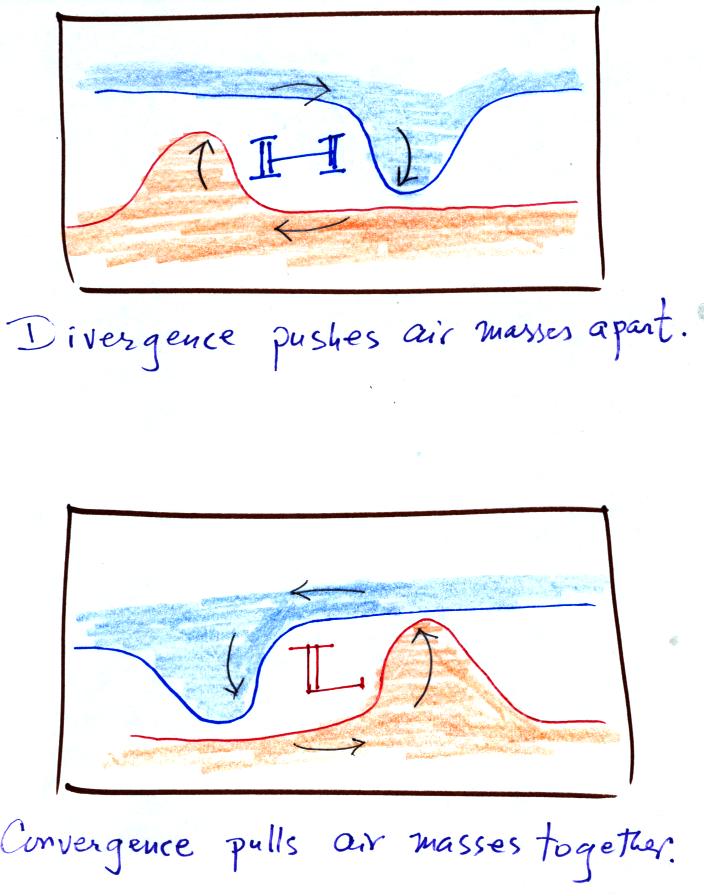

You find counterclockwise winds blowing around low

pressure. The

winds also spiral inward toward the center of the LOW (air will always

try to blow from high to low pressure, other forces may prevent it from

doing so however). The inward motion is called convergence.

Because

of the convergence air rises in the center of low pressure. The

rising air expands and cools. The cooling can cause clouds to

form. Convergence is one of

4 ways of causing air to rise in the atmosphere.

With high pressure winds spin clockwise and spiral outward

(divergence). Air

sinks in the middle of the high. The sinking air is compressed

(as it moves to lower levels in the atmosphere) and warms. The

warming keeps clouds from forming so you generally find clear skies in

the vicinity of surface high pressure.

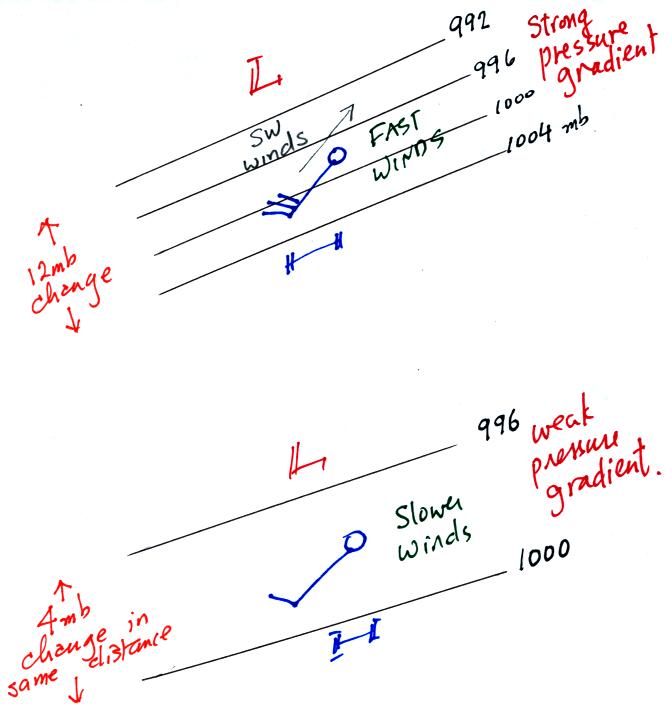

Once

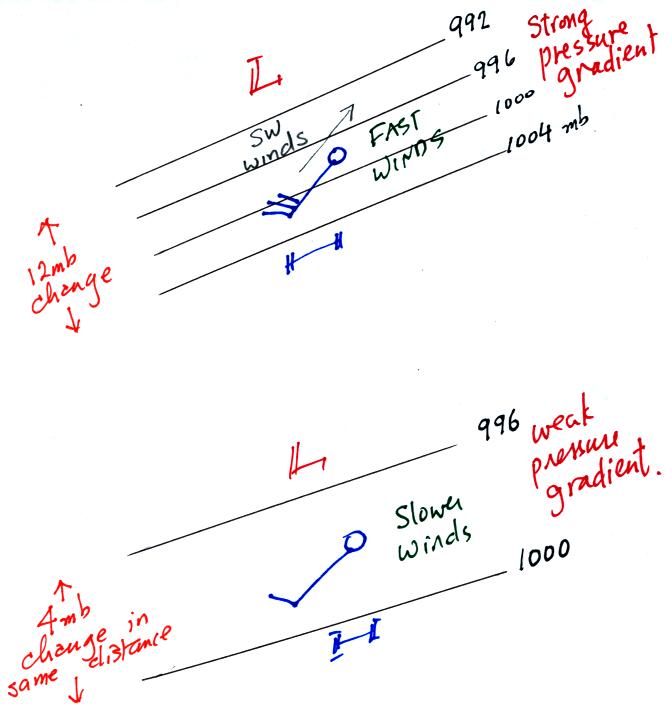

you have the pressure pattern mapped out you can look for regions where

the pressure gradient is strong or weak. The pressure gradient is

largely responsible for determining whether the winds will be fast or

slow.

In the top figure above the isobars are closely spaced. This is a

strong pressure gradient (a large or rapid change of pressure with

distance). The wind speed is 30 knots.

In the lower figure above the pressure change is smaller in about the

same horizontal distance. This is a weaker pressure gradient and

produces slower (10 knot) winds.

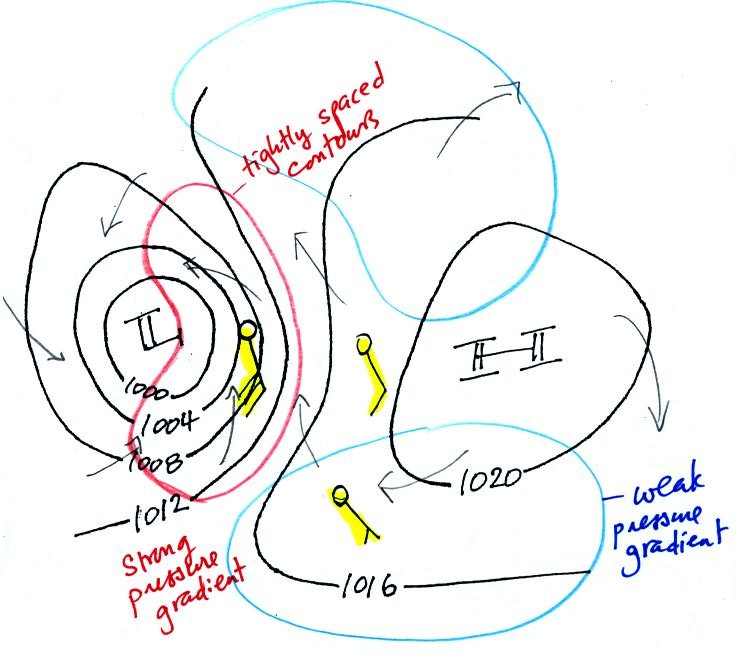

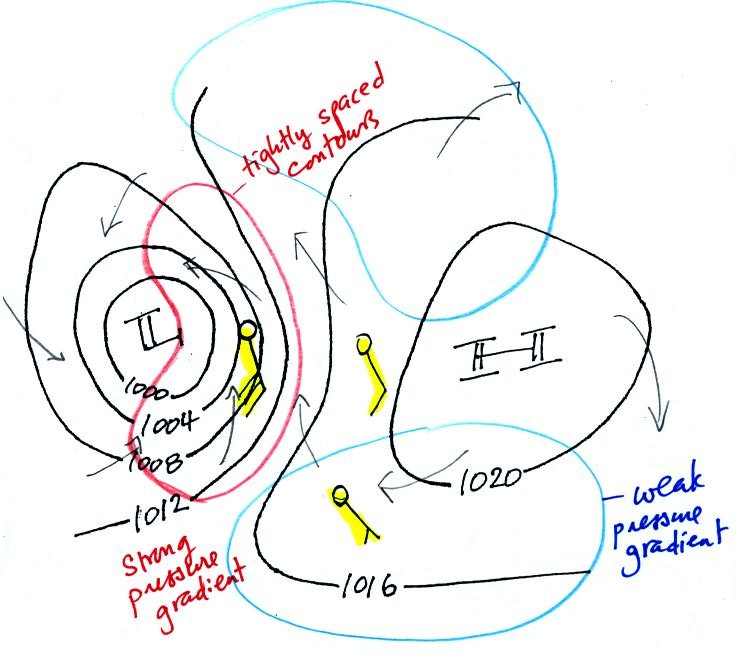

Here's a more complex but more realistic

weather map

example (found at the bottom of p. 40c in the photocopied class

notes). The arrows

indicate the directions of the winds (clockwise and outward around the

high, counterclockwise and inward around the low). Fast 30 knot

winds are found in the strong pressure gradient region shaded

red. Slower 10 knot and 5 knot winds are shown in the blue shaded

weak

pressure gradient region.

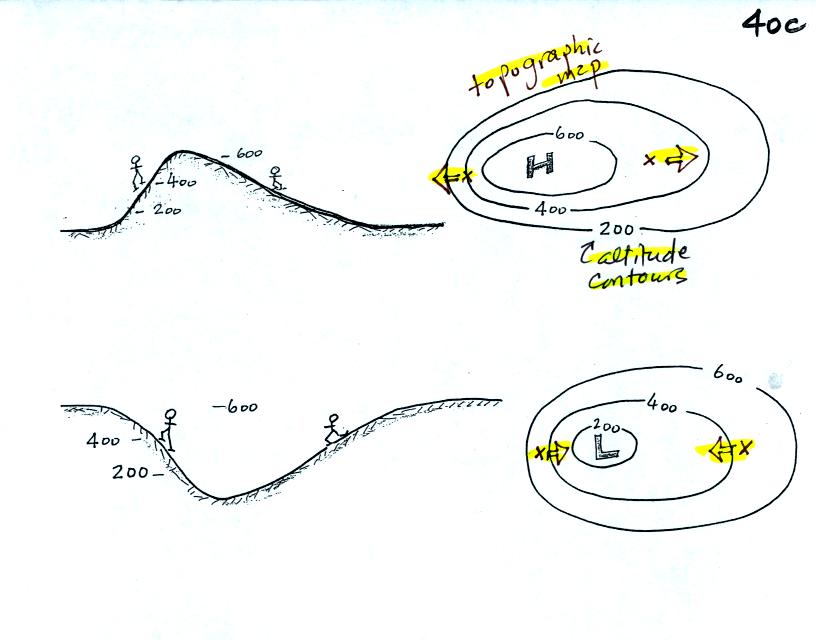

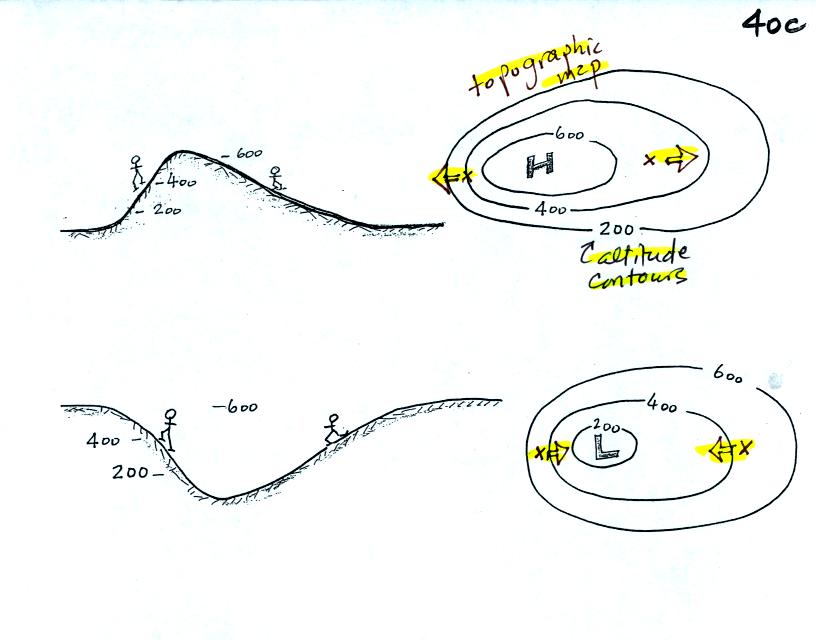

In some respects weather maps are like topographic

maps. The map

above at top right represents the hill at top left. Closely

spaced

contours on the topographic map correspond to a steep slope on the

hill. Widely spaced contours depict the gradual slope on the

right side of the hill. If you were to trip and roll downhill,

you would roll faster on the steep slope than on the gradual

slope.

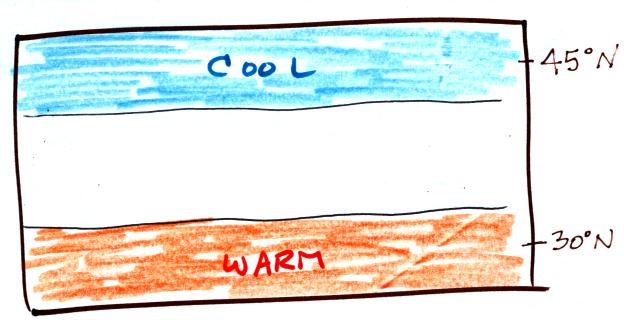

The

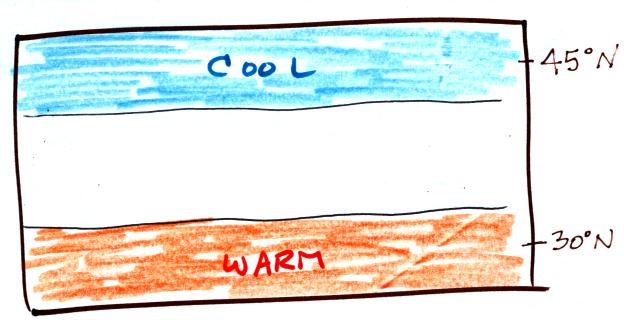

pressure pattern on a surface weather map determines the winds.

Once the winds begin to blow they can affect the temperature

pattern. The figure below shows the temperature pattern you would

expect to see if the wind wasn't blowing at all or if the wind was

blowing straight from west to east. The bands of different

temperature air are aligned parallel to the lines of constant latitude.

This isn't a very interesting

picture. It

gets a little

more interesting if you put centers of high or low pressure in the

middle.

The clockwise spinning winds move warm air to the north of the

western

side of the HIGH. Cold air moves toward the south on the eastern

side of the high.

Counterclockwise winds move cold air toward the south on the west side

of the LOW. Warm air advances toward the north on the eastern

side of the low.

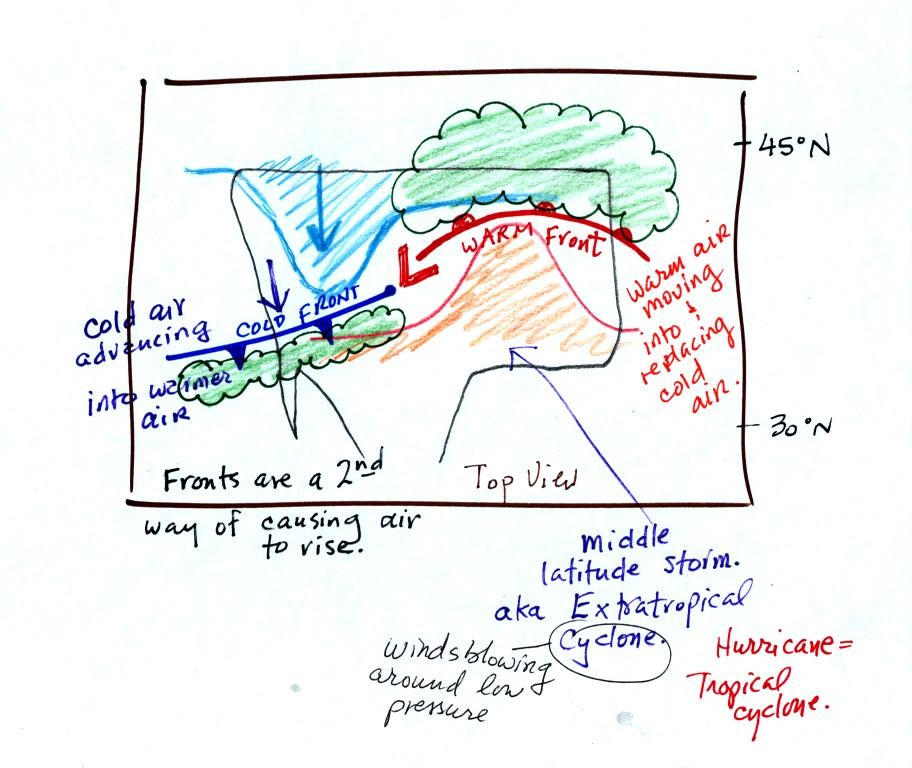

The converging winds in the case of low pressure will move the air

masses of different temperature in toward the center of low pressure

and cause them to collide with each other. The boundaries between

these colliding air masses are called fronts.

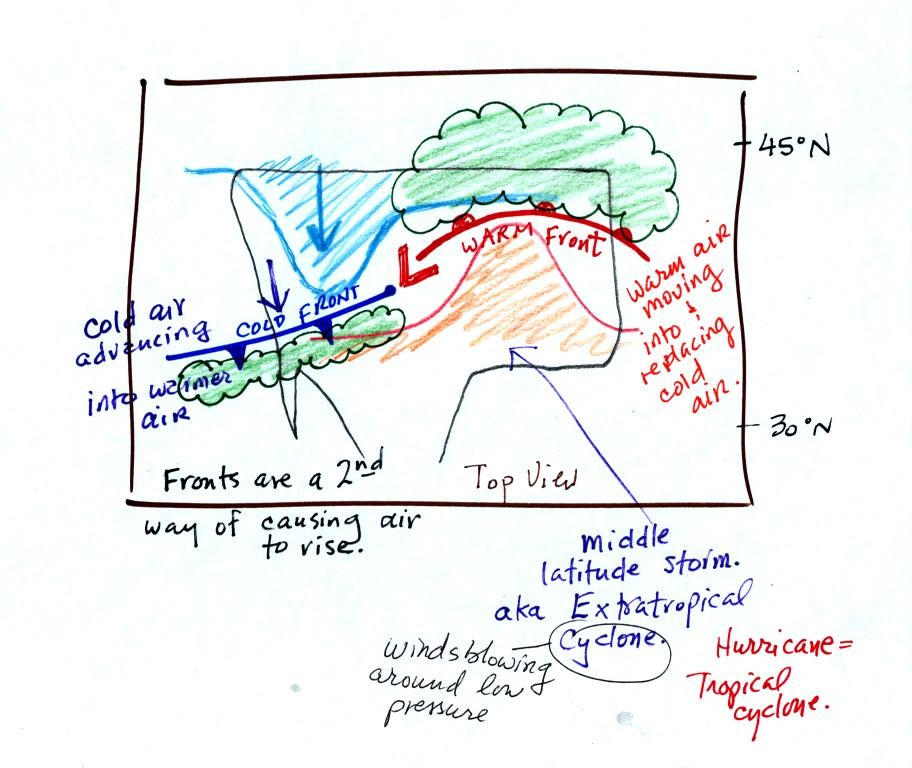

Cold air is moving from north toward the south on the

western side of

the low. The leading edge of the advancing cold air mass is a

cold front. Cold fronts are drawn in blue on weather maps.

The small triangular symbols on the side of the front identify it as a

cold front and show what direction it is moving. The fronts are

like spokes on a wheel. The "spokes" will spin counterclockwise

around the low pressure center.

A warm front (drawn in red with half circle symbols) is shown on the

right hand side of the map at the advancing edge of warm air.

Clouds can form along fronts (often in a fairly narrow band along a

cold front and over a larger area ahead of a warm front). We need

to look at the crossectional structure of warm and cold fronts to

understand better why this is the case.

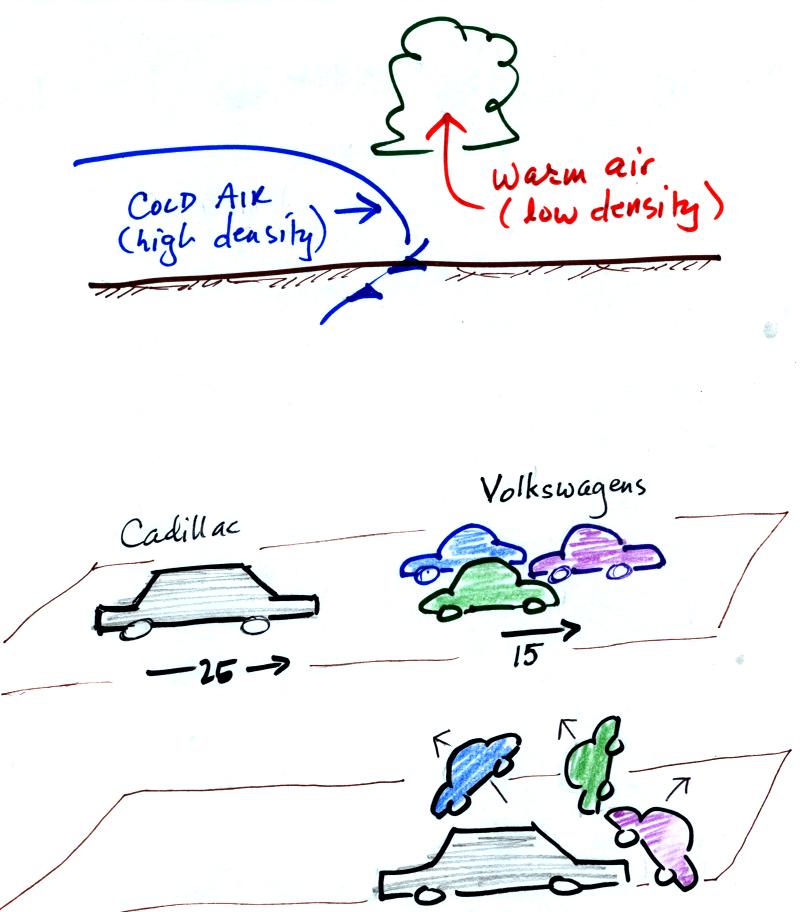

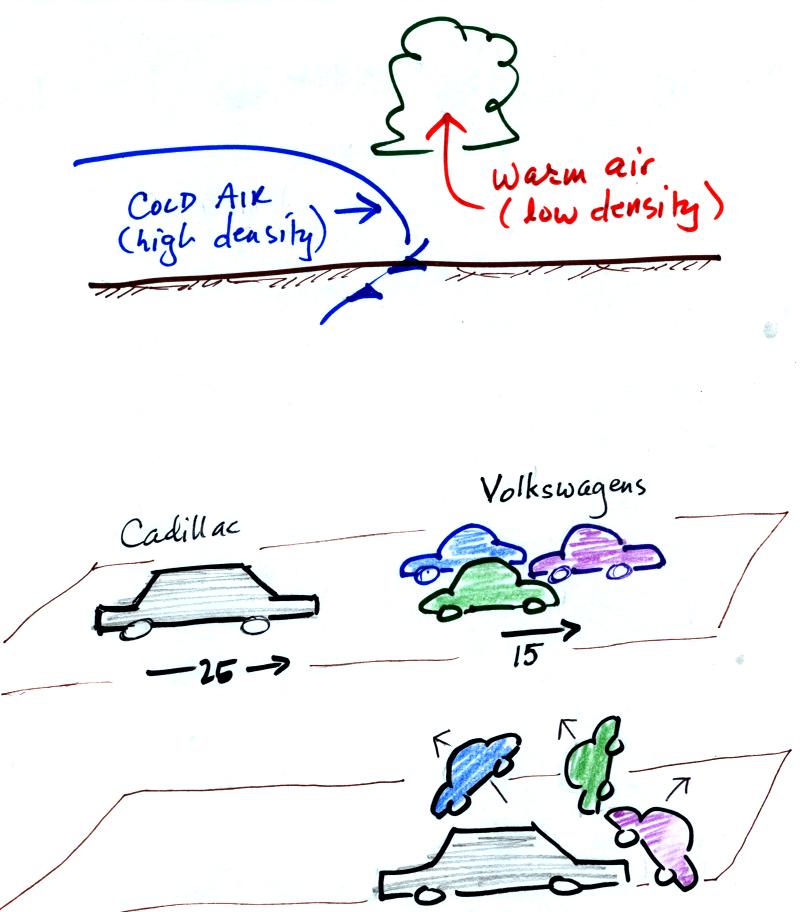

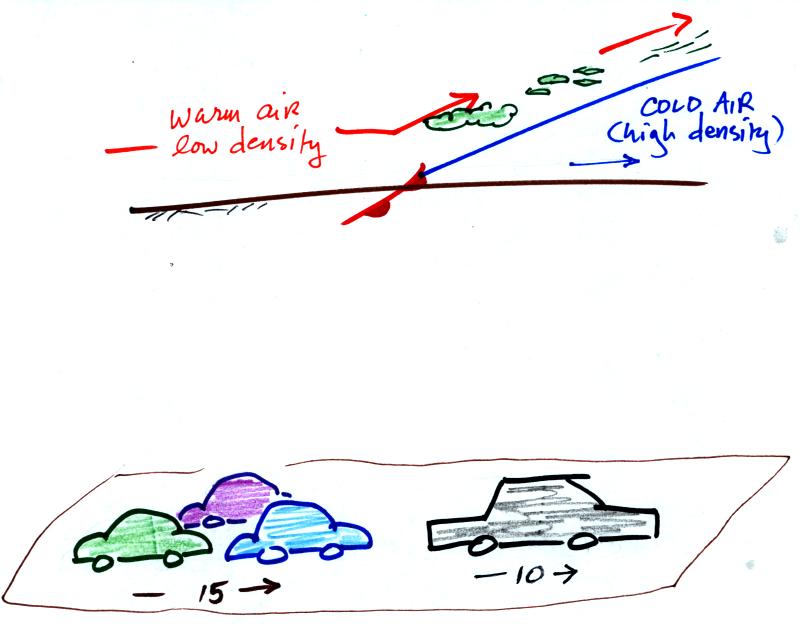

Crossectional

view of a cold front

At the top of the figure, cold dense air on the left is advancing

into

warmer lower density air

on the right. We are looking at the front edge of the cold air

mass. The warm low density air is lifted out of the way

by the cold air.

The lower figure shows a big heavy Cadillac plowing into a bunch of

Volkswagens. The VWs are through up into the air by the Cadillac.

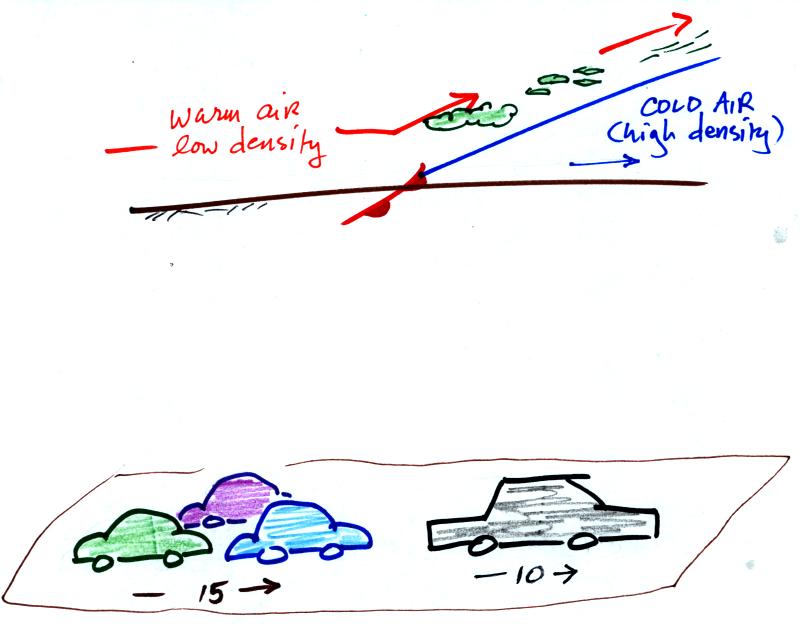

Crossectional

view of a warm front

In the case of a warm front we are looking

at the

back,

trailing edge of cold air (moving to the right). Note the ramp

like shape of the cold air mass. Warm air overtakes the cold

air. The warm air is still less dense than the cold air, it can't

wedge its way underneath the cold air. Rather the warm air

overruns the cold air. The warm air rises again (more gradually)

and clouds form. The clouds generally are spread out over a

larger area than with cold fronts.

In the lower figure the VWs are

catching a Cadillac. What happens

when they overtake the Cadillac?

The Volkswagens aren't heavy enough to lift the

Cadillac.

They run up and over the Cadillac.

Fronts (warm and cold) are a 2nd

way of causing rising air

motions in the atmosphere. Rising air cools and if the

warm air

is moist, clouds and precipitation can form.

Now we will go back to our surface weather map from last Friday's class.

We were trying to figure out what might have been causing the cloudy

weather in the NE and along the Gulf Coast. Part of the

reason for the clouds (and rain and drizzle) in the NE might have been

the converging winds around a center of Low pressure. This would

cause air to rise and could form clouds and precipitation. The

low wouldn't explain the rain shower along the Gulf Coast, however.

Now we have added cold and warm fronts to the map (you'll learn more

about how this is done later in the semester). The warm front may

be a large part of what is causing the cloudy weather in the NE.

The rain showers along the Gulf Coast are almost certainly being caused

by the approaching cold front.

Remember you won't be tested on

the following material on Quiz #1.

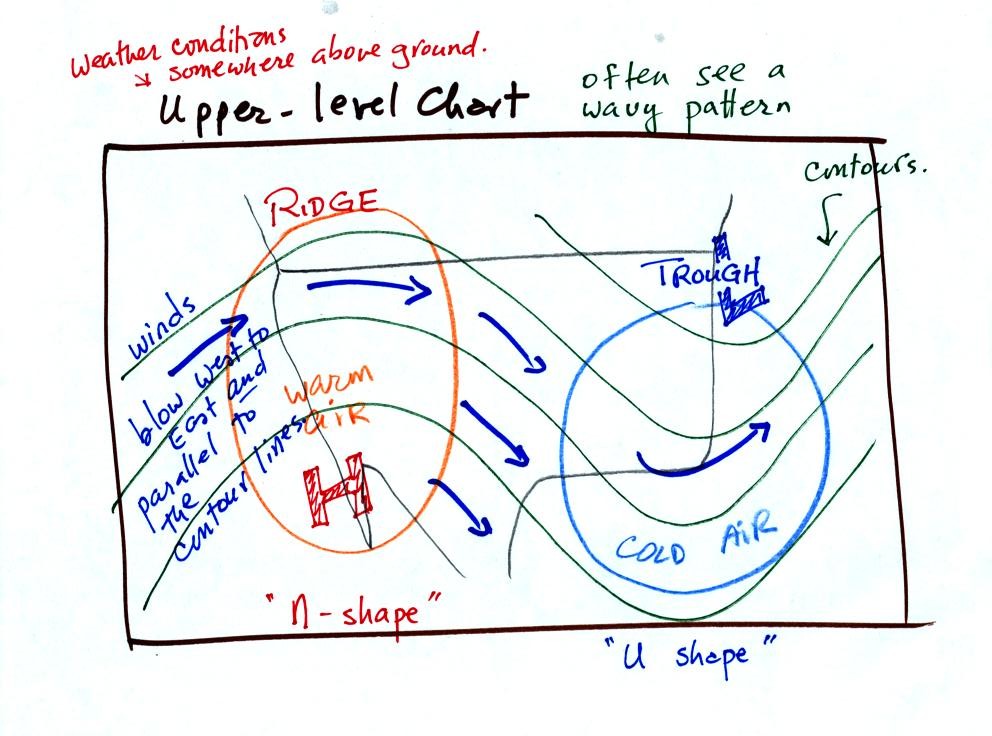

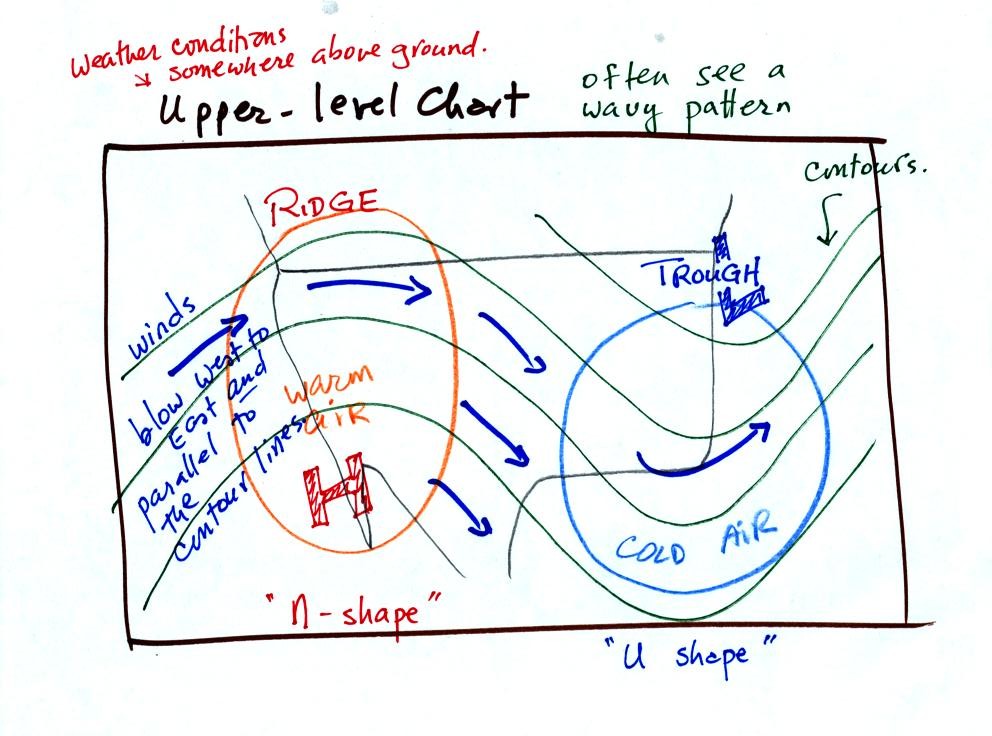

Next we'll

look briefly at some of the features found on upper level weather

charts. We'll also see how upper level and surface features

interact.

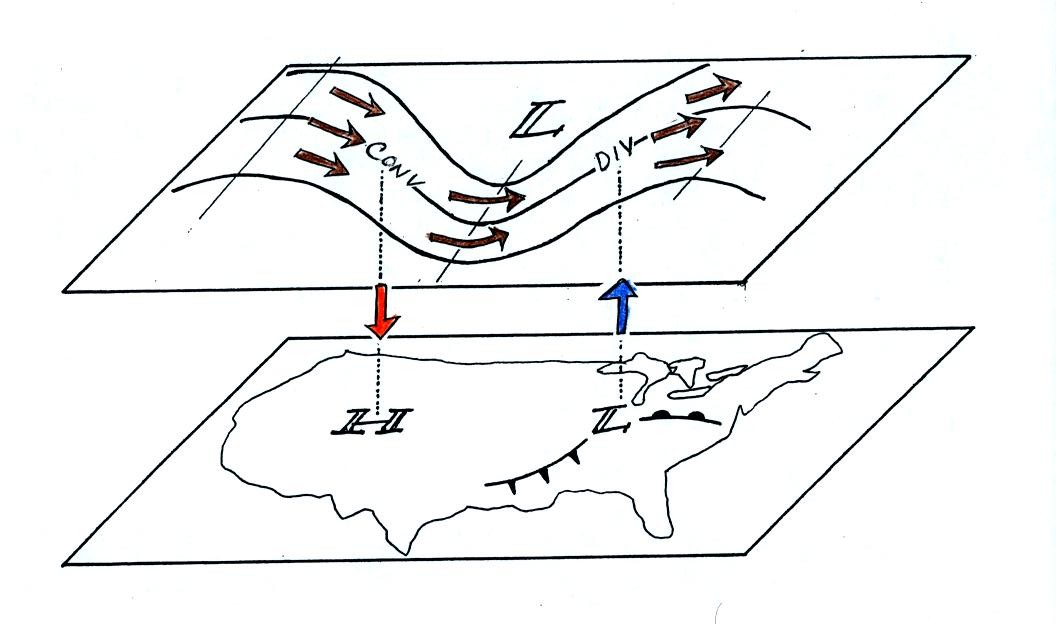

Upper level just refers to some level above the

ground.

Upper level weather maps are often drawn for several levels at

different altitudes above the ground. The upper level pattern

generally has a wavy appearance like shown above. The contours

lines dip toward the south in troughs and bulge up toward the north in

ridges. You generally find cold air below an upper level trough

(cold air between the ground the level the map is drawn for) and warm

air under an upper level ridge. The winds blow from west to east

parallel to the contour lines (winds blow across the contour lines

slightly, toward low pressure, on surface weather maps).

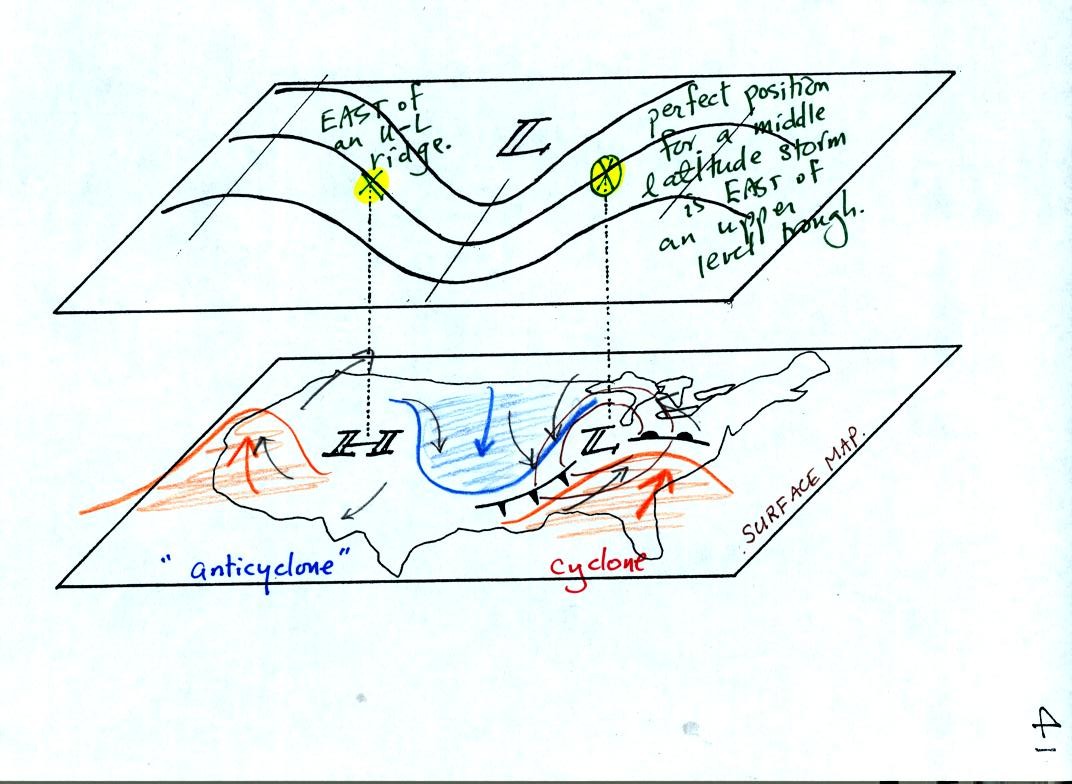

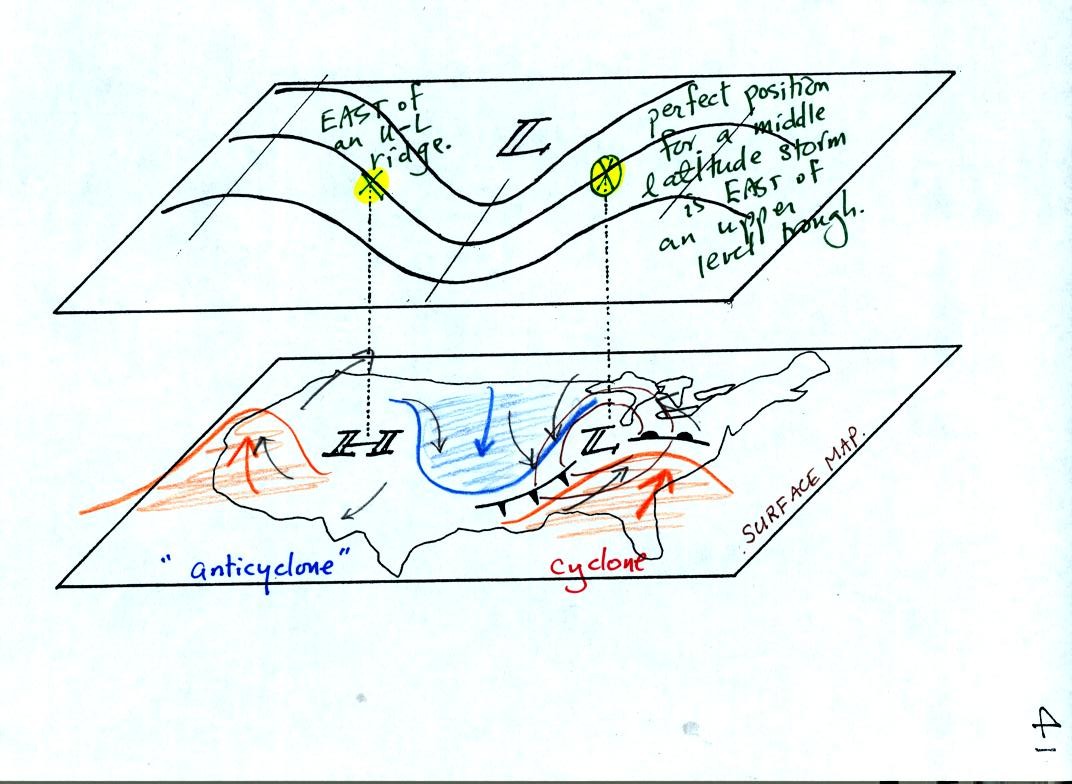

Now we will put the two kinds of maps together. On the

surface map you see centers of HIGH and LOW pressure.

The low pressure center, together with the cold and warm fronts, is a

middle latitude storm or extratropical cyclone. A surface center

of HIGH pressure is also called an anticyclone.

Note how the counterclockwise winds spinning around the LOW move cold

air (this was shaded blue after class) southward (behind the cold front

on the western side of the LOW). Clockwise winds spinning around

the HIGH also move cold air into the region between the HIGH and the

LOW. This bunch of cold air lies directly below the upper level

trough. Remember how the previous figure explained that you would

find cold air below and upper level trough. Now you can begin to

understand where that cold air comes from.

Similarly the winds move warm air northward on the west side of the

HIGH and the east side of the LOW (south of the warm front).

These warm air regions lie below ridges on the eastern and western

edges of the upper level chart. The orange shaded warm air

regions were added after class.

Note the X marked on the upper level chart directly above the

surface LOW. This is a good location for a surface LOW to develop

and strengthen. The reason why is that this is a location where

upper level divergence

can be found. (The point east of an upper level ridge is a

location where upper level convergence can be found, this can cause the

surface high pressure to get even higher)

We'll see in the next figure how upper level

divergence can cause the pressure at the center of a surface low to get

even lower. Upper level divergence can cause a surface storm to

intensify.

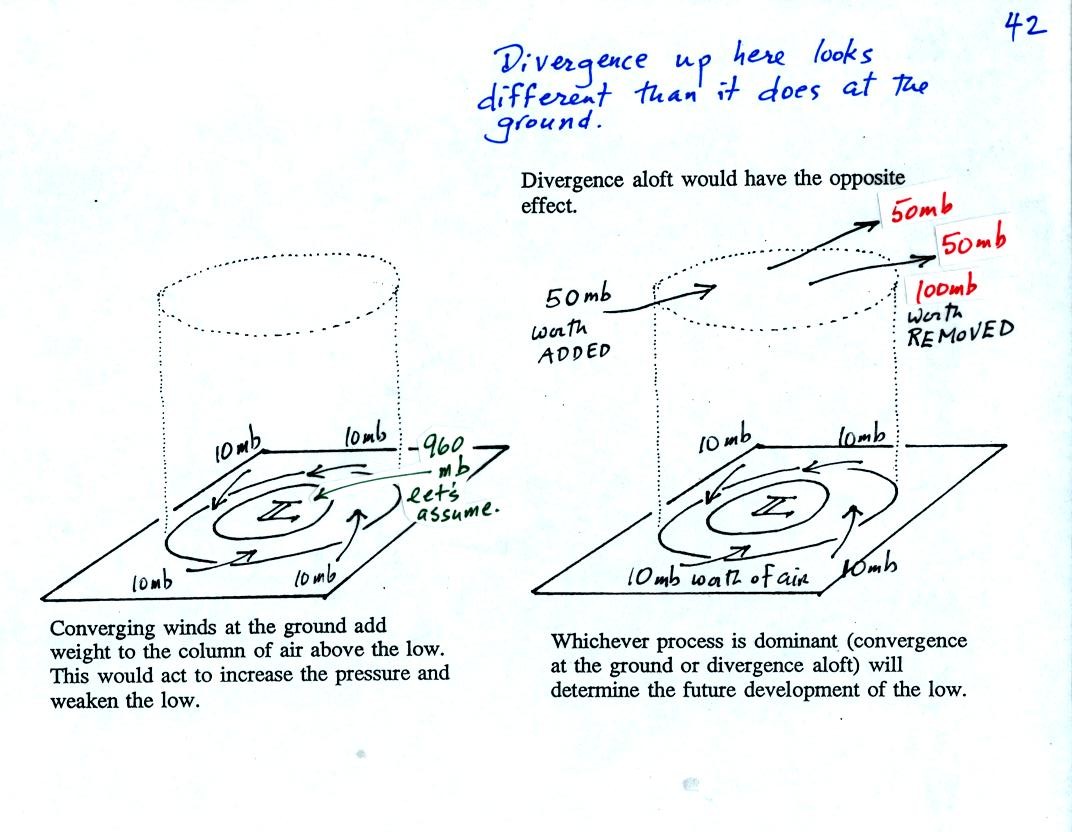

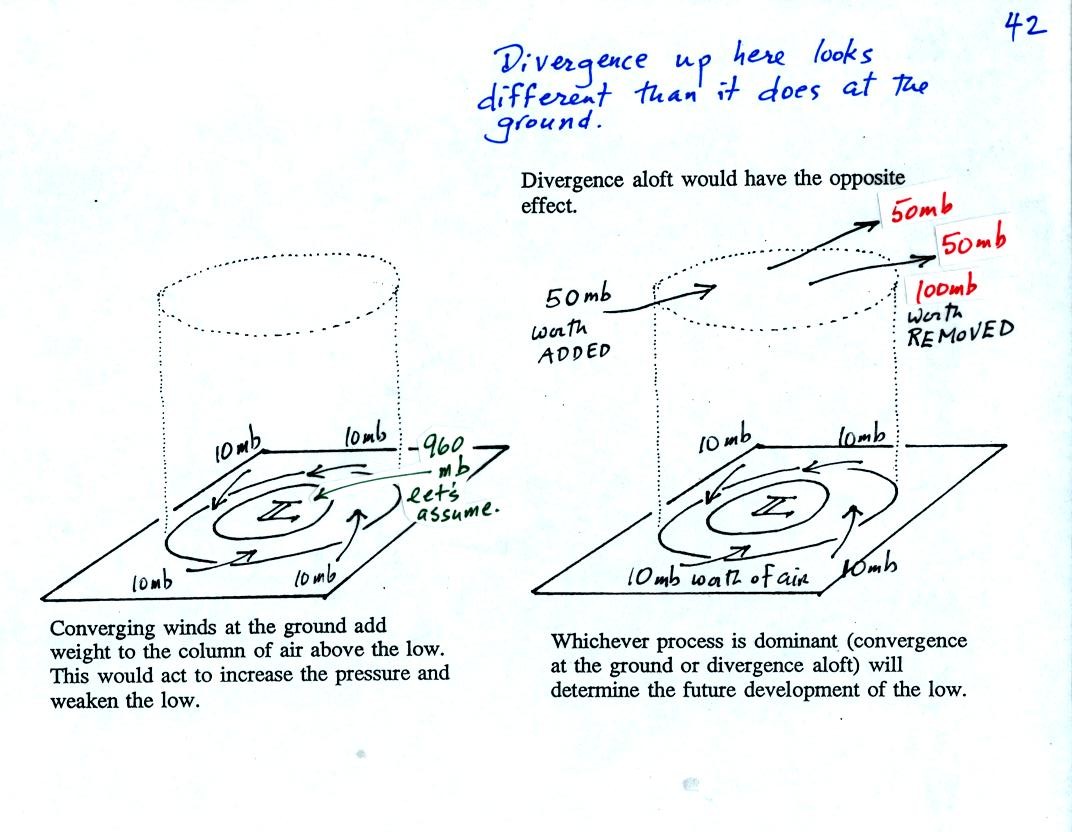

We'll start with the figure at left (modified somewhat after class).

We see a surface LOW (we'll pretend the pressure is 960

mb). Winds are spinning counterclockwise and spiraling in

toward (converging) the center of the low. These surface winds

are moving air into the column of air and (as explained on the figure)

should cause the pressure in the center of the LOW to increase.

Imagine that each arrow brings in enough air to increase the pressure

at the center of the LOW by 10 mb. You would expect the pressure

at the center of the LOW to increase from 960 mb to 1000 mb. What

if the central pressure actually decreased? How would you explain

that?

This is just like a bank account. You have $960 in the bank and

make four $10 dollar deposits. You would expect your bank account

balance to increase from $960 to $1000. What if your account

balanced dropped? How would you explain that?

The right hand figure shows what is going on. We haven't included

the effects of addition and removal of air at upper levels.

Imagine that 50 mb worth of air are added to the column and 50+50=100

mb worth of air are removed. That's a net removal (net

divergence) of 50 mb.

So now we have 40 mb worth of air being added at the ground (surface

convergence) and 50 mb worth being removed at upper levels (upper level

divergence). The grand total is 10 mb of removal. The

surface pressure will decrease slightly (from 960 mb to 950 mb).

You can apply the numbers in the right hand picture to the bank account

problem. You have $960 in the bank and make four $10

deposits.

However you also deposit $50 dollars and make two $50 withdrawals (the

top of the picture). That's a total of $90 being deposited and

$100 being withdrawn. Your bank account goes down $10.

In a case like

this where upper

level divergence > surface convergence, the surface LOW

pressure will get even lower (the low will "deepen") and the storm will

strengthen. Click here if

you dare and if you would like to see what could happen next.

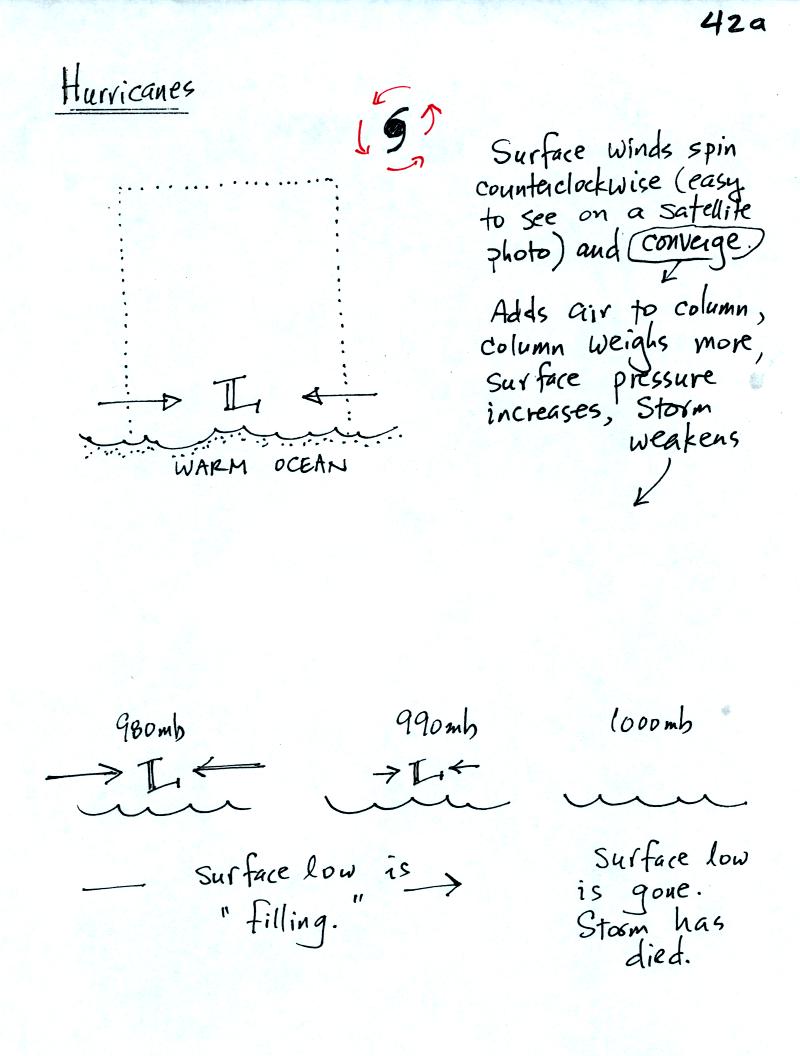

The other possibility is that the upper level divergence <

surface convergence. In this case the LOW pressure will

increase (the low will "fill") and the storm will weaken.

Click here for some additional

examples. By working through some additional examples you might

increase your understanding of this material and build up your

confidence (of course there's always a chance that more examples will

just make this topic more confusing - the choice is yours)

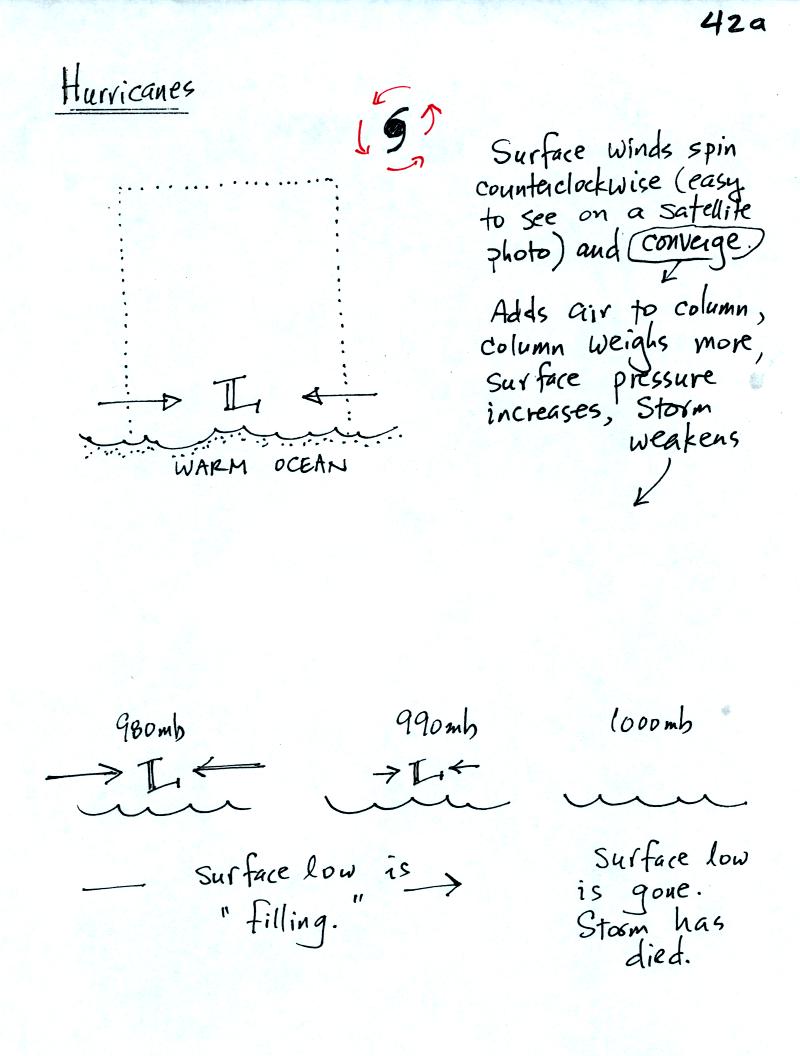

We

finished by applying these concepts to hurricanes.

You find surface low pressure in the center of a hurricane (a

general name for a hurricane is tropical cyclone- the word cyclone

refers to the winds that spin around low pressure).

Record-setting low sea level pressure values have all been observed in

hurricanes.

In this first picture we consider the converging surface winds

only. These winds will add air to the cylinder of atmosphere that

is the hurricane. This will increase the surface pressure and the

storm will fill (surface pressure will increase) and the storm will

weaken. The storm would eventually dissipate.

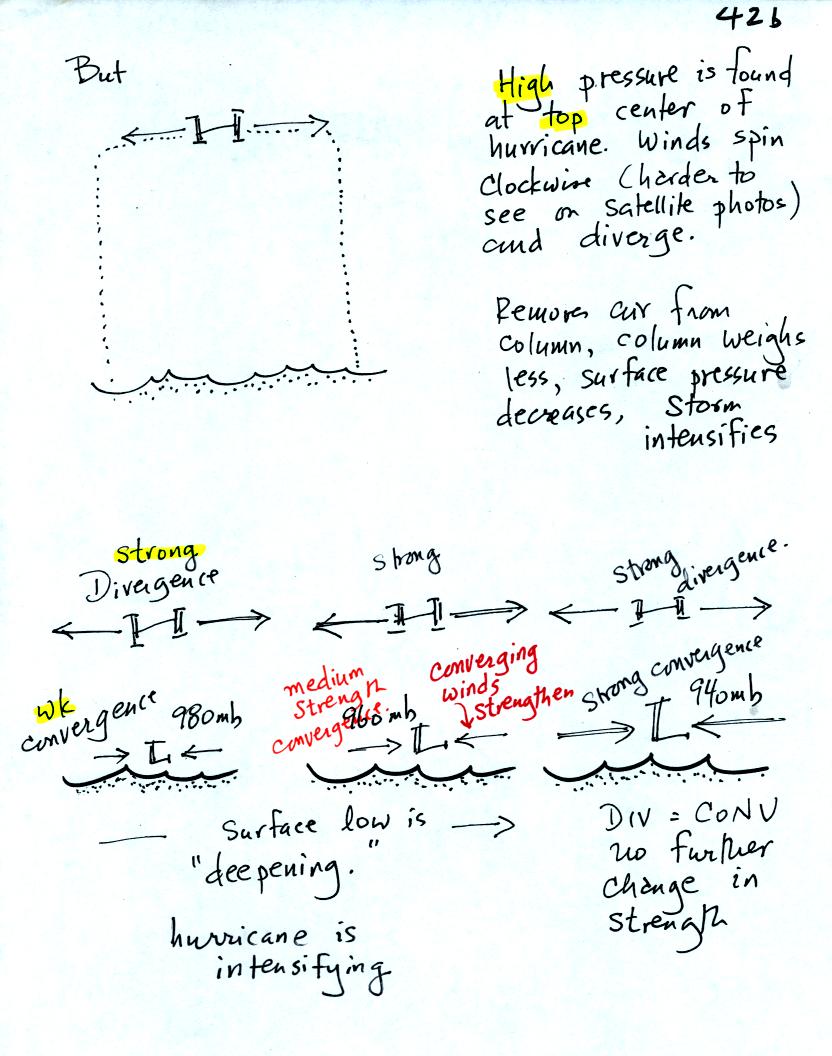

Now we know that sometimes hurricanes strengthen despite the converging

winds that blow at the surface.

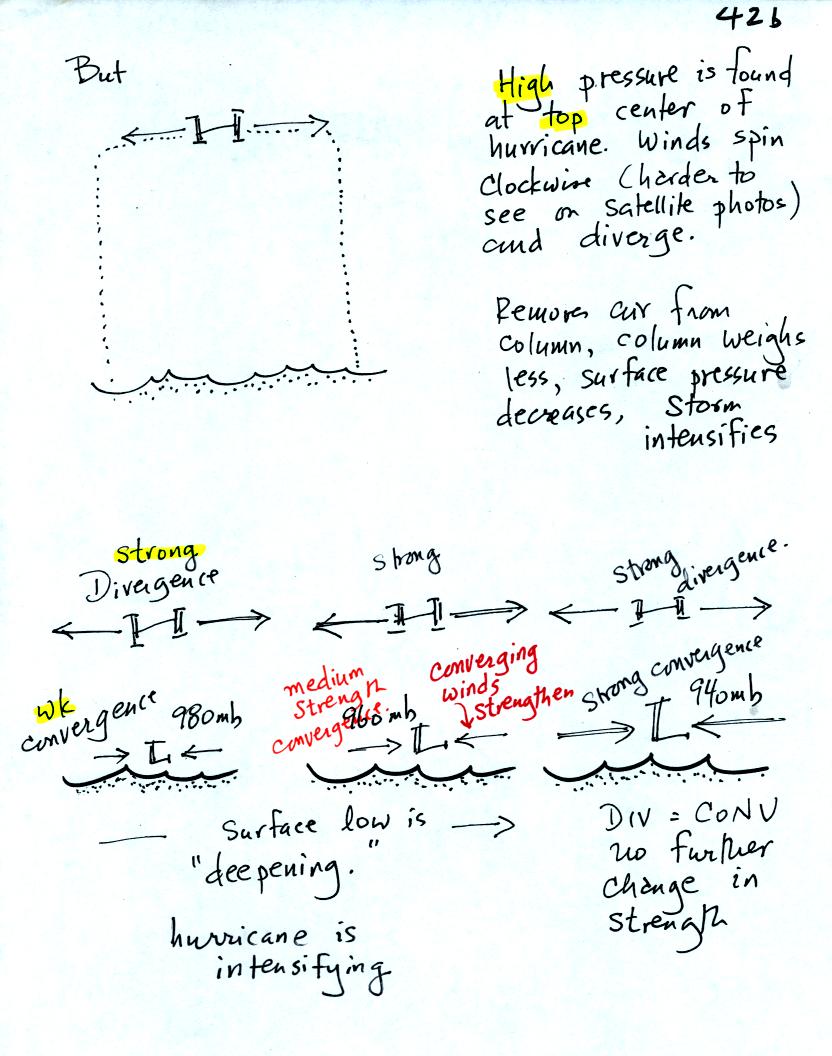

We will find, later in the semester, that high pressure is found at the

tops of hurricanes. This means the upper level winds will

diverge. If the upper level divergence exceeds the surface

convergence, air will be removed from the colume, the surface pressure

will get lower, and the hurricane will strengthen. This is

illustrated at the bottom of the figure above.

This

figure wasn't shown or discussed in class.

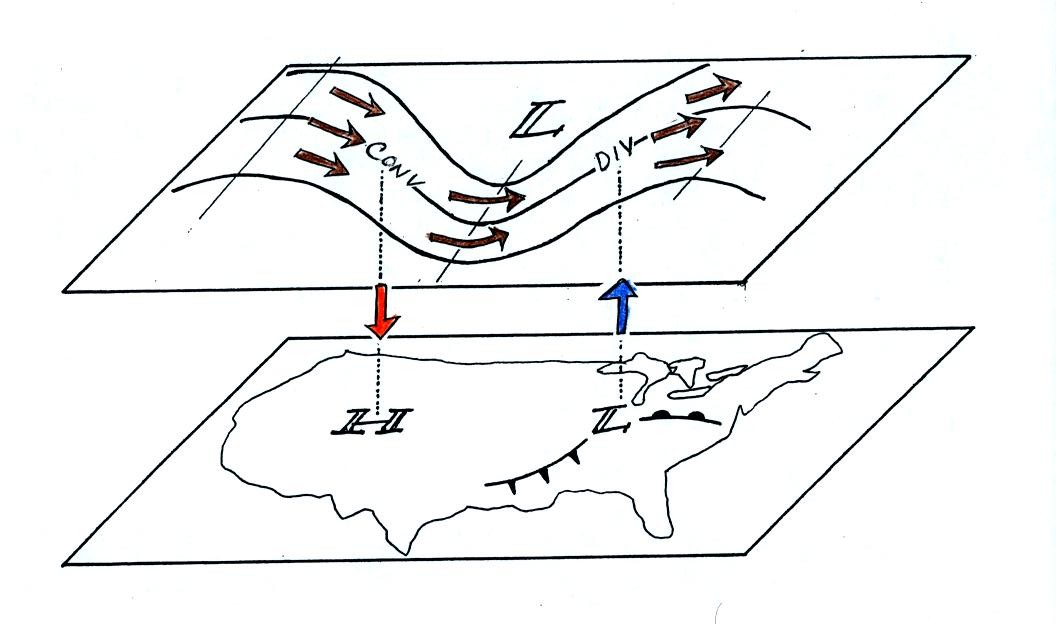

Now that you have some idea of what upper level divergence looks like

you are in a position to understand another one of the relationships

between the surface and upper level winds.

One of the things we have learned about surface LOW pressure is that

the converging surface winds create rising air motions. The

figure above gives you an idea of what can happen to this rising air

(it has to go somewhere). Note the upper level divergence in the

figure: two arrows of air coming into the point "DIV" and three arrows

of air leaving (more air going out than coming in is what makes this

divergence). The rising air can, in effect, supply the extra

arrow's worth of air.

Three arrows of air come into the point marked "CONV" on the upper

level chart and two leave (more air coming in than going out).

What happens to

the extra arrow? It sinks, it is the source of the sinking air

found above surface high pressure.