Tuesday Dec. 7, 2010

A couple of songs from the Royal Crown Revue

("Hey Pachuco" and "The Walkin' Blues"). Seemed like just the

right kind of stuff to end the semester with.

Everything in my possesion as of last Friday has been graded and

was returned in class today together with grade summaries.

The Final Exam for this class is Thursday, Dec. 16 from 8-10 am in ILC

140. You can take the final with the other section this coming

Friday, 2-4 pm in CESL 103. Please let me know ahead of time if

you plan to do that.

Today's

pictures of the day. Clockwise from upper left:

Fox, Rajah, stray cat #1, stray cat #2.

We

will

spend the last day of class on Hurricanes.

This will be the final

topic

that we cover this semester. This won't be on this week's quiz

but will most likely be on the Final Exam.

A good place to begin is to compare hurricanes (tropical cyclones)

with

middle latitude storms (extratropical cyclones). The middle

column below list some similarities, the outer columns list

differences. These are not details that you need to worry about

for the Final Exam.

|

Middle latitude storms

|

Similarities

|

Hurricanes

|

1

|

form at middle latitudes

(30 to 60 degrees latitude)

|

both types of storms have

low pressure centers

(cyclone refers to winds blowing around low pressure)

|

from in the subtropics

(5 to 20 degrees latitude)

|

2

|

can form over land or water

|

upper level divergence is

what causes

both types of storms to intensify

|

only form over warm ocean

water

|

3

|

bigger (might cover half

the US)

|

|

not as big (might fill the

Gulf of Mexico)

|

4

|

fronts separate warm and

cold air masses

|

|

just warm moist air

|

5

|

at middle latitude the

prevailing westerly winds move these storms from west to east

|

|

the trade winds move

hurricanes from east to west

|

6

|

strongest in the winter

into early spring

|

|

strongest in late summer

into fall (when the ocean is warmest)

|

7

|

produce rain, snow, sleet,

graupel |

|

mostly just rain (lots of

rain) |

8

|

usually no name

|

|

get names

|

Hurricanes receive names (when they reach tropical storm

strength). The names now alternate male and female. The

names of particularly strong or deadly hurricanes (such as Katrina) are

retired, otherwise the names repeat every 6 years.

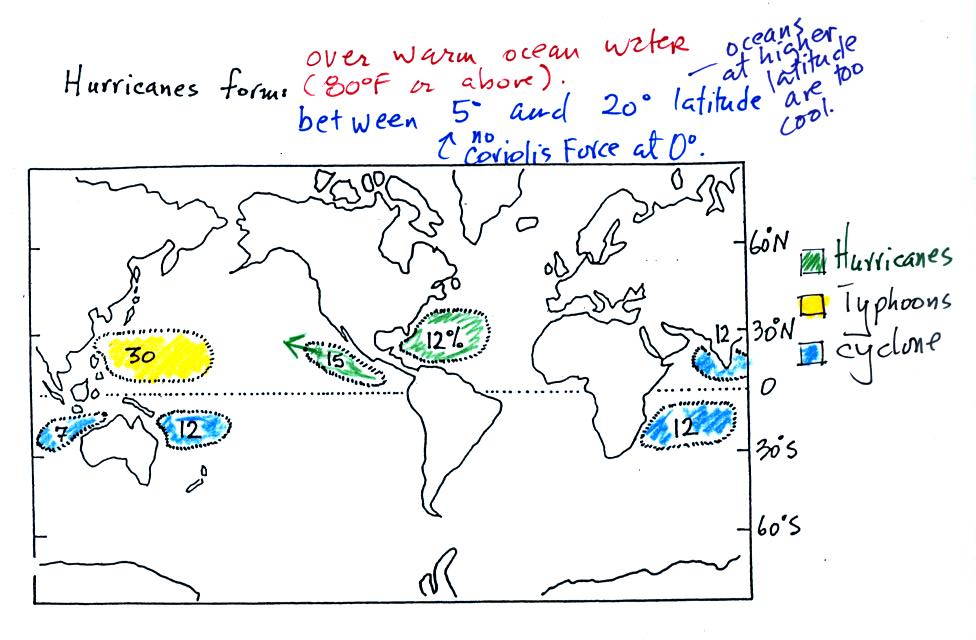

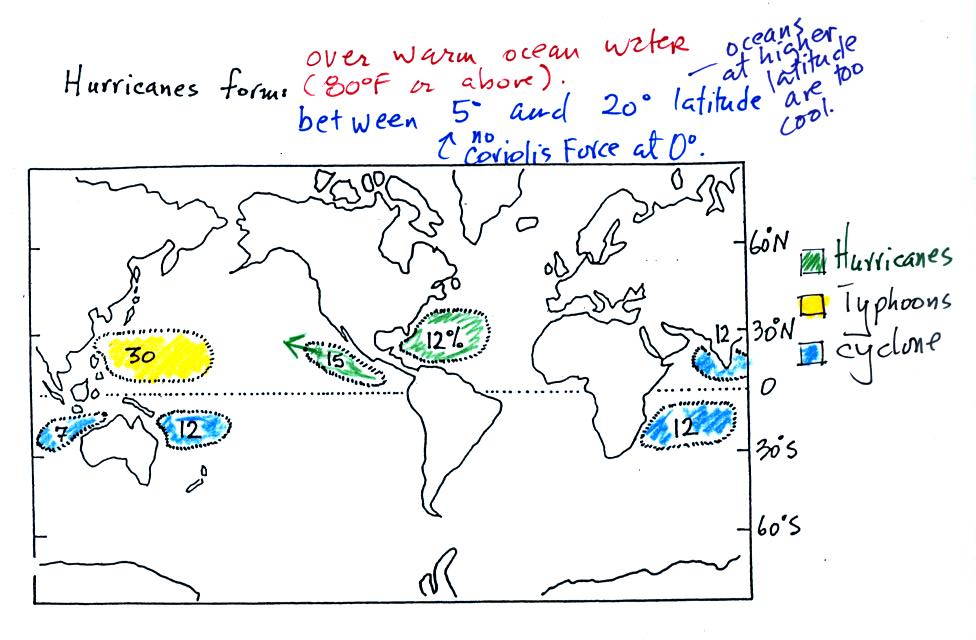

Hurricanes form between 5 and 20 degrees latitude,

over warm ocean

water, north and south of the equator. The warm

layer of water

must be fairly deep to contain enough energy to fuel a hurricane and so

that turbulence and mixing don't bring cold water up to the ocean

surface. The atmosphere must be unstable so that thunderstorms

can develop. Hurricanes will only form when there is very little

or no vertical wind shear (changing wind direction or speed with

altitude). Hurricanes don't form at the equator because there is

no Coriolis force there (the Coriolis force is what gives hurricanes

their spin and it causes hurricanes to spin in opposite directions in

the northern and southern hemispheres).

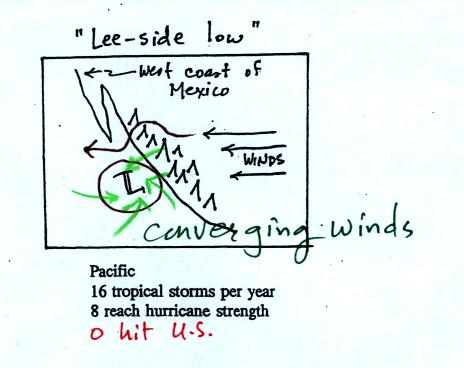

Note that more tropical

cyclones form off the

west coast of the US than

off the east coast. The west coast hurricanes don't generally get

much attention, because they move away from the coast and usually

don't

present a threat to the US (except occasionally to the state of

Hawaii). The moisture from these storms will

sometimes be pulled up into the southwestern US where it can lead to

heavy rain and flooding.

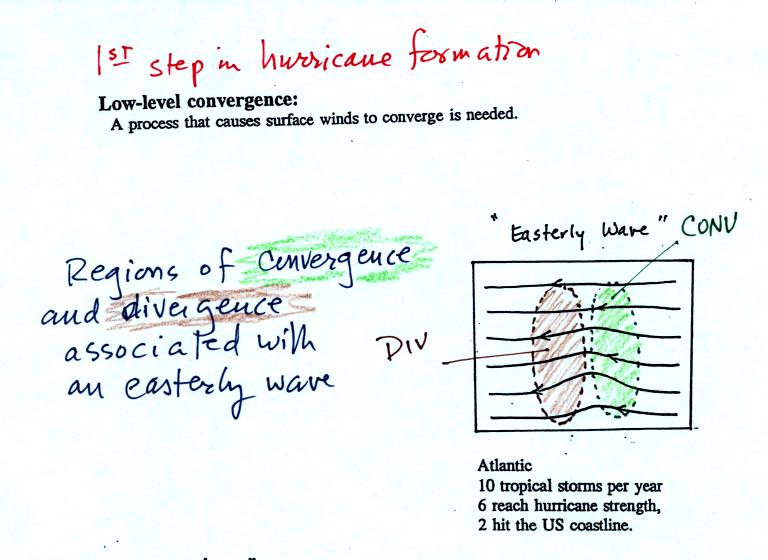

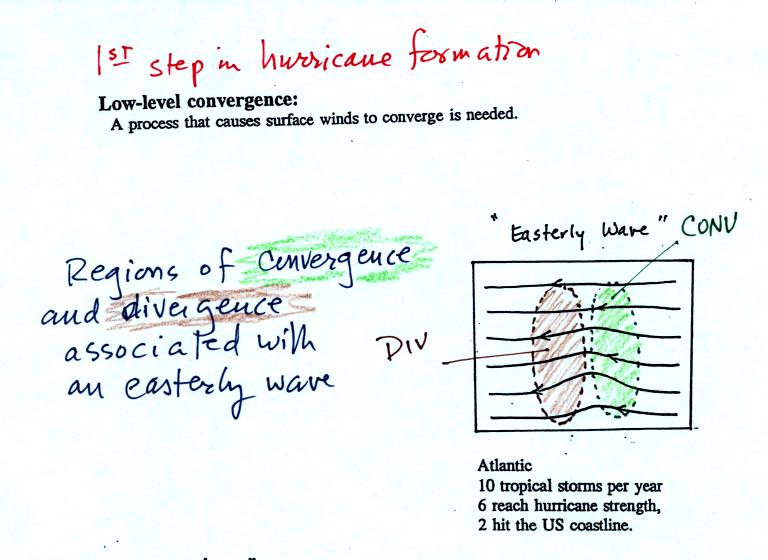

Some kind

of meteorological process that produces low

level

convergence

is needed to initiate a hurricane. One possibility, and the one

that fuels most of the strong N. Atlantic hurricanes, is an "easterly

wave." This is just a "wiggle" in the wind flow pattern.

Easterly waves often form over Africa or just off the African coast and

then travel toward the west across the N. Atlantic. Winds

converge as they approach the wave and then diverge once

they are

past it . The convergence will cause air to rise and

thunderstorms

to begin to develop.

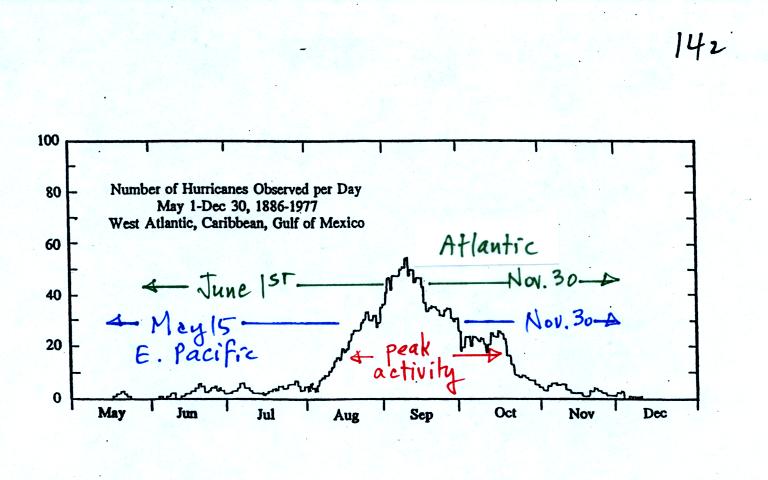

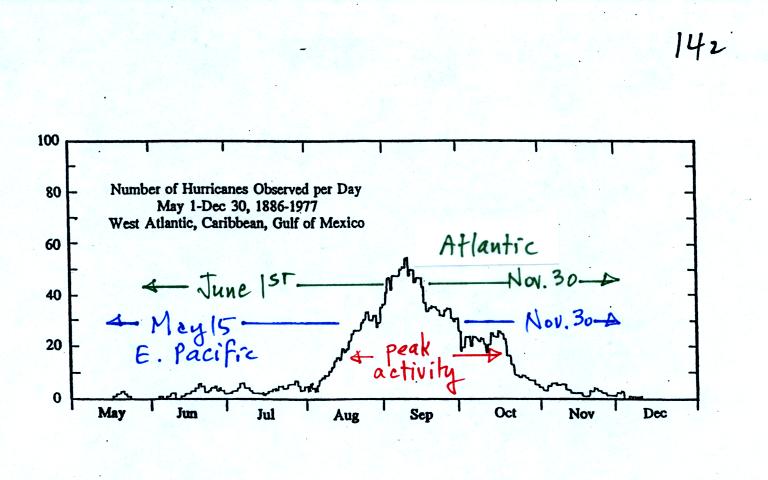

In an average year, in the N.

Atlantic, there will be 10 named

storms

(tropical storms or hurricanes) that develop during hurricane

season. 2005 was, if you remember, a very unusual

year. There

were 28 named storms in the N. Atlantic in 2005. That beat the

previous record of 21 names storms that had been set in 1933. Of

the 28 named storms, 15 developed into hurricanes.

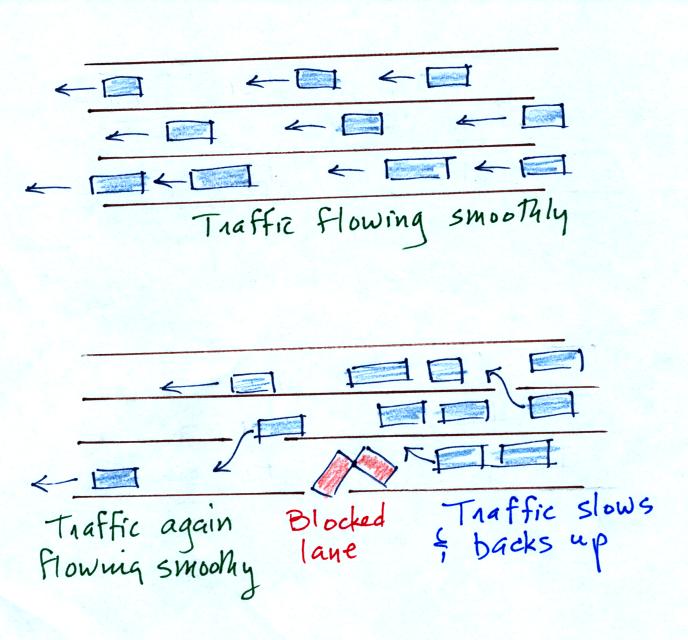

In some ways winds blowing through an easterly wave resembles

traffic

on a multi-lane highway. Traffic will back up as it approaches a

section of the highway with a closed lane. Once through the

"bottleneck" traffic will begin to flow more freely.

Another process that causes surface

winds to converge is a "lee side low."

This

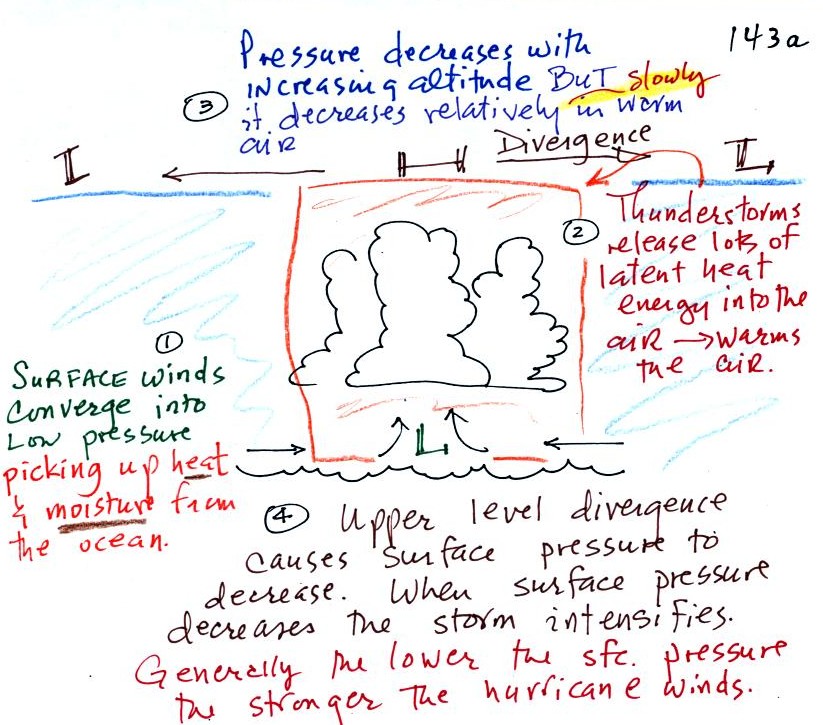

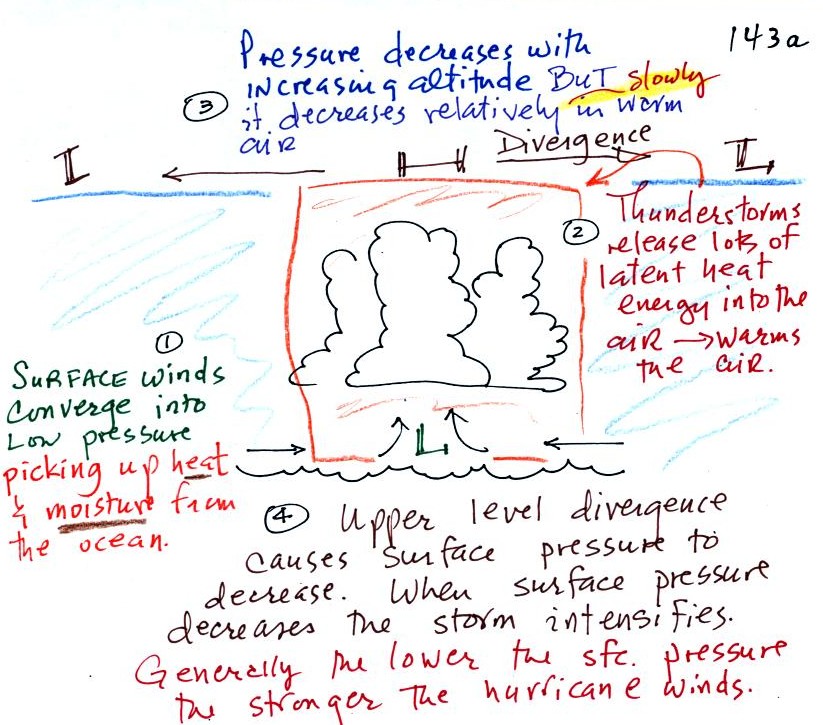

figure tries to explain how a

cluster of thunderstorms can organize and intensify into a hurricane.

1. Converging surface winds pick

up heat and moisture from the ocean. These are the two mains

sources of energy for the hurricane.

2. Rising air expands, cools, and thunderstorm clouds

form. The

release of latent heat during condensation warms the atmosphere.

The core of a hurricane is warmer than the air around it.

3. Pressure decreases more slowly with increasing altitude

in the warm core of the hurricane. The result is that pressure at

the top center of the hurricane is higher than the pressure at the top

edges of the hurricane (pressure at the top center is still lower than

the

pressure at the bottom center of the hurricane). Upper levels

winds diverge and spiral outward

from the top center of the hurricane (you can sometimes see this on

satellite photographs of hurricanes).

4. The upper level divergence will cause the surface

pressure at the center of the hurricane to decrease. The speed of

the converging surface winds increases

and the storm intensifies. The converging winds pick up

additional heat and moisture which warms the core of the hurricane even

more. The upper level high pressure and the upper level

divergence increase. The increased divergence lowers the surface

pressure even more.

Here's another view of hurricane development and intensification

(not shown in

class)

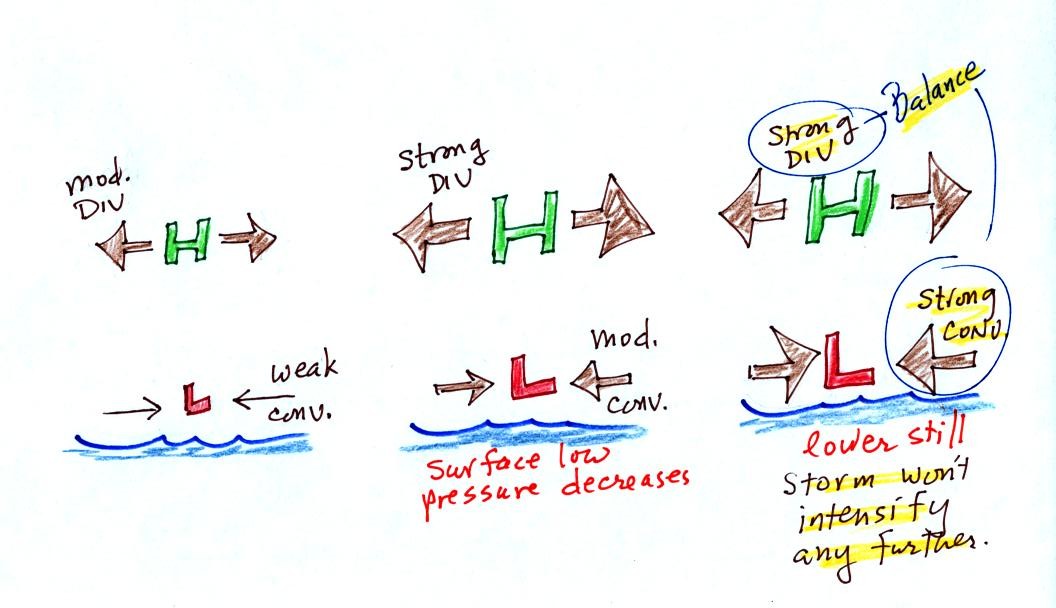

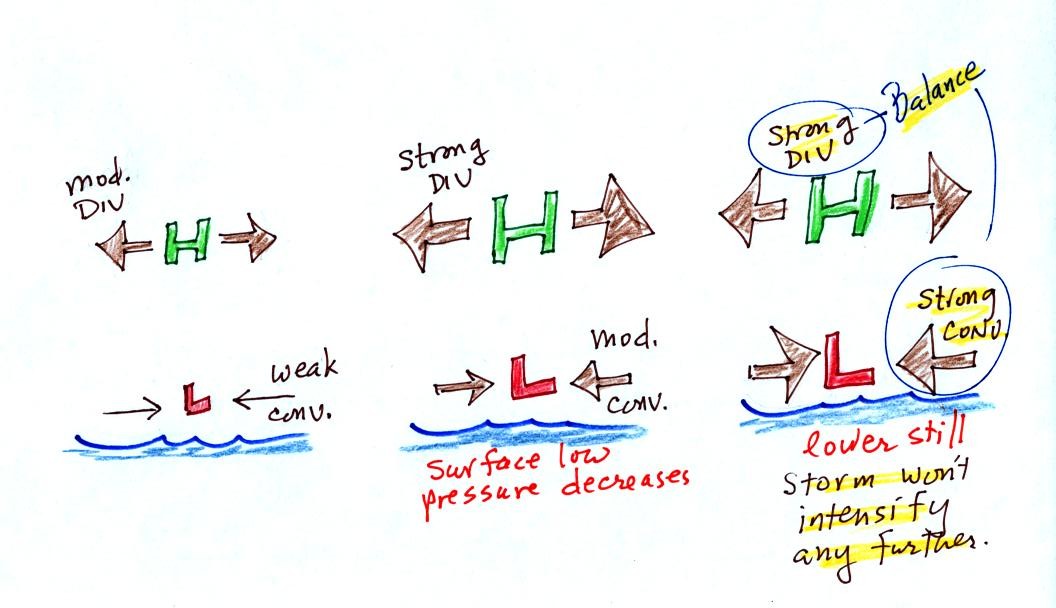

In the figure at left the upper level

divergence is stronger than the

surface convergence. Divergence is removing more air than is

being added by surface convergence. The surface low pressure will

decrease. The decrease in surface pressure will cause the

converging surface winds to blow faster.

In the middle picture, the surface low pressure is lower, the surface

convergence is stronger. The upper level divergence has also been

strengthened a little bit. The upper level divergence is still

stronger than the surface convergence so the surface so the surface low

pressure will

decrease even more.

In the right figure the surface low pressure has decreased enough that

the surface convergence now balances the upper level divergence.

The storm won't strengthen any more.

Generally speaking the lower the surface pressure at the center of a

hurricane the stronger the storm and the faster the surface winds will

blow. The following figure (not shown in class)

shows

this

This figure tries to show the relationship between surface

pressure and surface wind speed. The world record low

sea level pressure reading, 870 mb, was set

by Typooon Tip off the SE Asia coast in 1979. Sustained winds in

that storm were 190

MPH. Three 2005 Atlantic hurricanes: Wilma, Rita, and Katrina had

pressures in the 880 mb to 900 mb range and winds ranging from 170 to

190 MPH.

The stages

of storm development that lead up to a hurricane are shown

at the bottom of p. 143a in the photocopied ClassNotes.

A tropical disturbance is just a localized cluster of

thunderstorms

that a meterologist might see on a satellite photograph. But this

would merit observation because of the potential for further

development. Signs of rotation would be evidence of organization

and the developing storm would be called a tropical depression.

In order to be called a tropical storm the storm must

organize a little

more, and winds must

increase to 35 knots. The storm receives a name at this

point. Finally when winds exceed 75 MPH (easier to remember than

65 knots or 74 MPH) the storm becomes a hurricane.

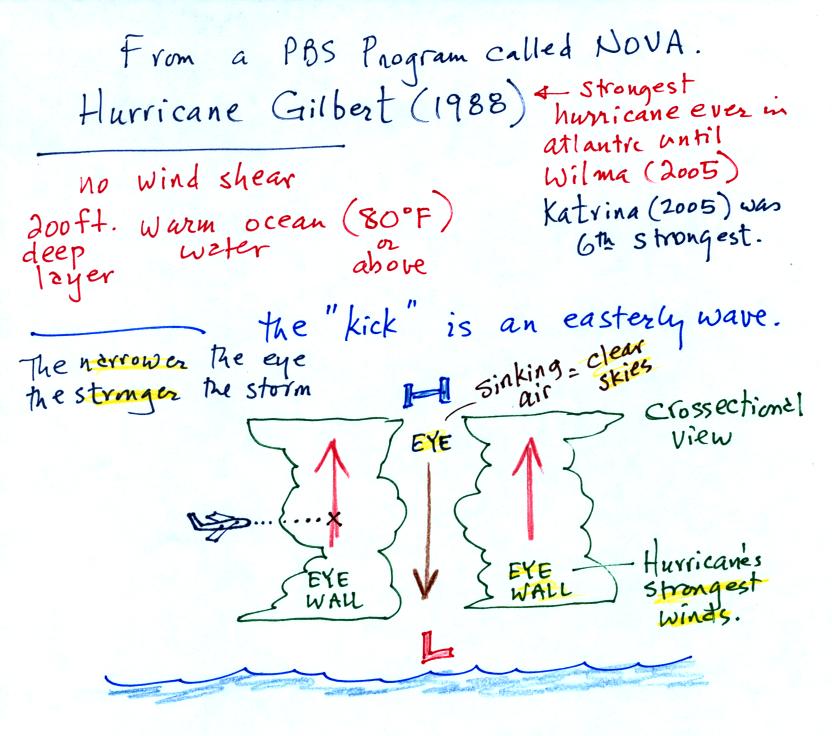

A crossectional view of a mature

hurricane (top) and a

picture

like you might

see on a satellite photograph (below).

Sinking air in the very center of a hurricane produces the clear

skies

of the eye, a hurricane's most distinctive feature. The eye is

typically a few 10s of miles across, though it may only be a few miles

across in the strongest hurricanes. Generally speaking the

smaller the eye, the stronger the storm.

A ring of strong thunderstorms, the eye wall, surrounds the

eye.

This is where the hurricane's strongest winds are found.

Additional concentric rings of thunderstorms are found as you move

outward from the center of the hurricane. These are called rain

bands. These usually aren't visible until you get to the outer

edge of the hurricane because they are covered by high altitude layer

clouds.

That was all the new material we had time to cover in class

because a

20

minute segment from a NOVA program (PBS network) on hurricanes was

shown. A film crew was on board a NOAA

reconnaissance plane as it flew into the narrow eye of hurricane

GILBERT. Gilbert set the record low sea level pressure reading

for the Atlantic ocean (888 mb). That record stood until the 2005

hurricane season when WILMA set a new record of 882 mb. The world

record low sea level pressure, 870 mb, was set in a SE Asian typhoon in

1979.

Here are some comments shown during the video. We

will review the Saffir Simpson scale in class on Monday.

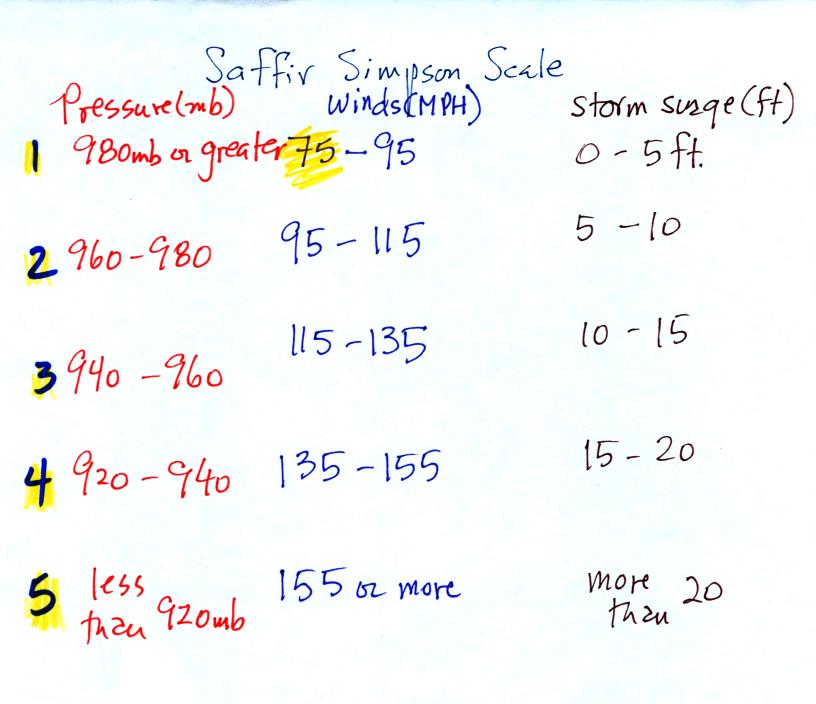

Here's a simplified version of the

Saffir-Simpson scale used to rate hurricane strength or intensity.

You should remember that the scale

runs from 1 to 5 and that winds need

to be 75 MPH or greater in order for a tropical storm to become a

hurricane.

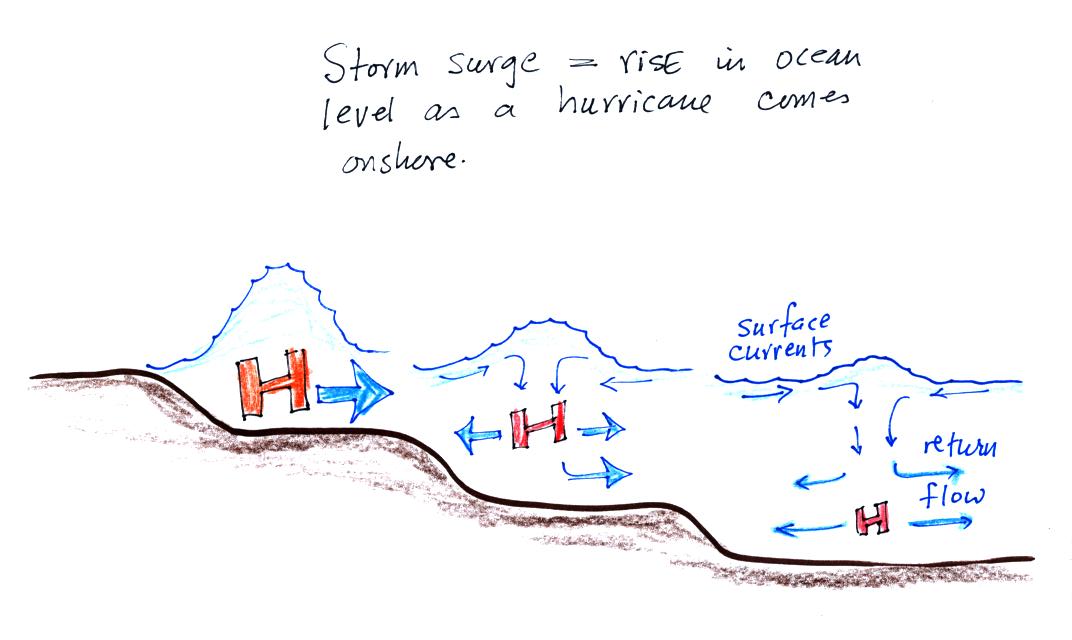

A hurricane storm surge is a rise in ocean level caused when

a hurricane moves onshore. It causes most of the destruction

along a coastline. The

following figure shows how a storm surge develops.

Out at sea,

the converging surface

winds

create

surface

currents

in the

ocean that transport water toward the center of the hurricane.

The rise in ocean level is probably only a few feet, though the waves

are much larger. A return flow develops underwater that carries

the water back to where it came from.

As the hurricane approaches shore, the

ocean becomes

shallower.

The return flow must pass through a more restricted space. A rise

in ocean level will increase the underwater pressure and the return

flow will speed up. More pressure and an even faster return flow

is needed as the hurricane gets near the coast. The rise in ocean

level can be more than 20 feet for a category 5 hurricane.

Here is a link to the storm surge website

(from the Hurricane Research Division of the Atlantic Oceanographic and

Meteorological Labororatory). It has an interesting animation

showing output from the SLOSH model used to predict hurricane storm

surges and the flooding they can cause.

And with that we came to

THE END

of what we will be able to cover in

NATS 101 this semester. In class on Wednesday we will begin

the review for next week's Final Exam.