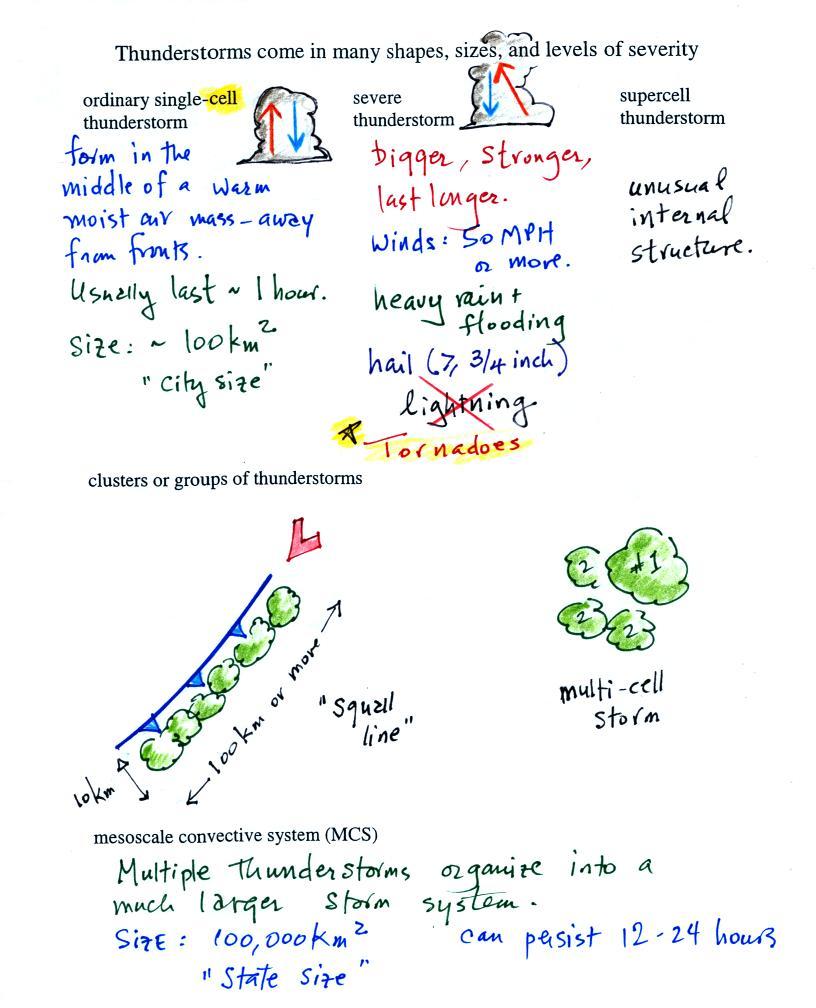

Thunderstorms come in different

sizes and levels of

severity. We will mostly be concerned with ordinary

single-cell thunderstorms

(also referred to as air mass thunderstorms). They form in the

middle of warm moist air, away from front. Most summer

thunderstorms in Tucson are this type. An air mass

thunderstorm has a vertical updraft. A cell is just a

thunderstorm "unit."

Tilted updrafts are found in severe and supercell

thunderstorms. As we shall see this allows those storms to get

bigger, stronger, and

last longer. The tilted updraft will sometimes begin

to rotate. We'll see this

produces an interesting cloud feature called a wall cloud and tornadoes.

Supercell

thunderstorms

have

a complex internal

structure; we'll watch a short

video at some point that shows a computer simulation of the complex air

motions inside a supercell thunderstorm.

We won't spend anytime discussing mesoscale convective systems

except to say that they are a much larger storm system. They can

cover a large portion of a state. They move slowly and often

thunderstorm activity can persist for much of a day. Occasionally

in the summer in Tucson we'll have activity that lasts throughout the

night. This is often caused by an MCS.

The

following somewhat tedious material was intended to

prepare you to better appreciate a time lapse video movie

of a thunderstorm developing over the Catalina mountains. I don't

expect you to remember all of the details given below. The

figures below are more carefully drawn versions of what was done in

class.

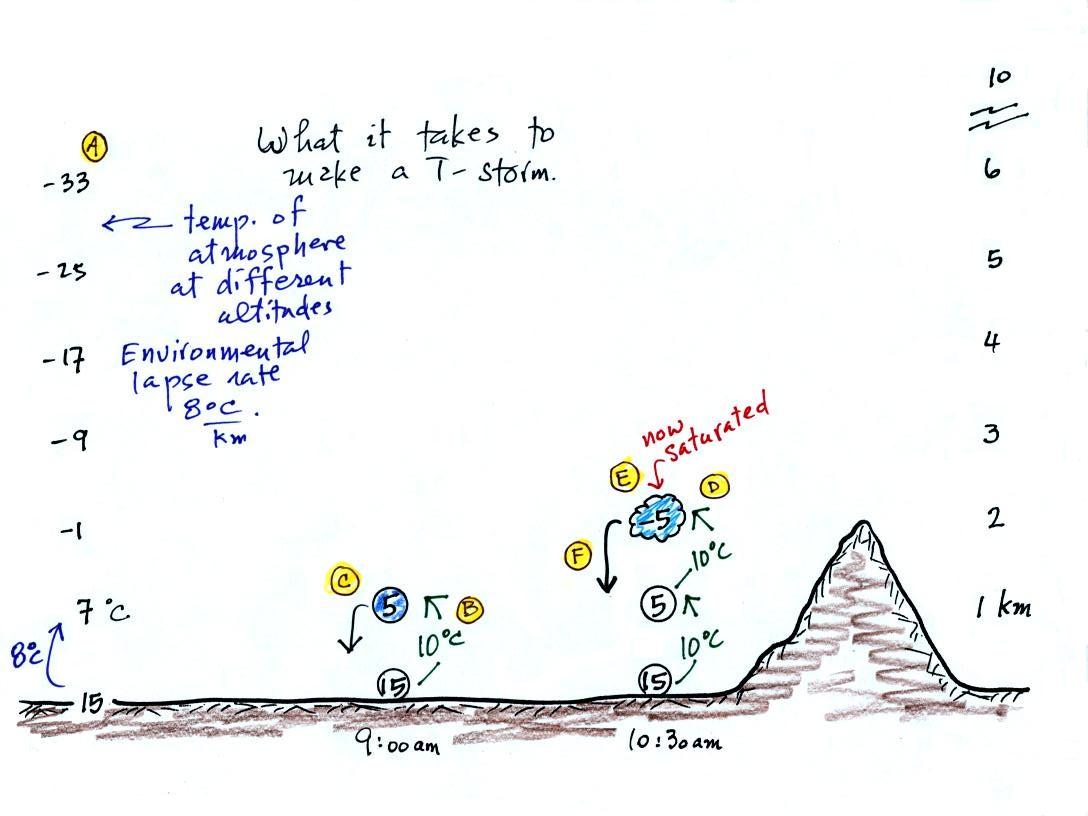

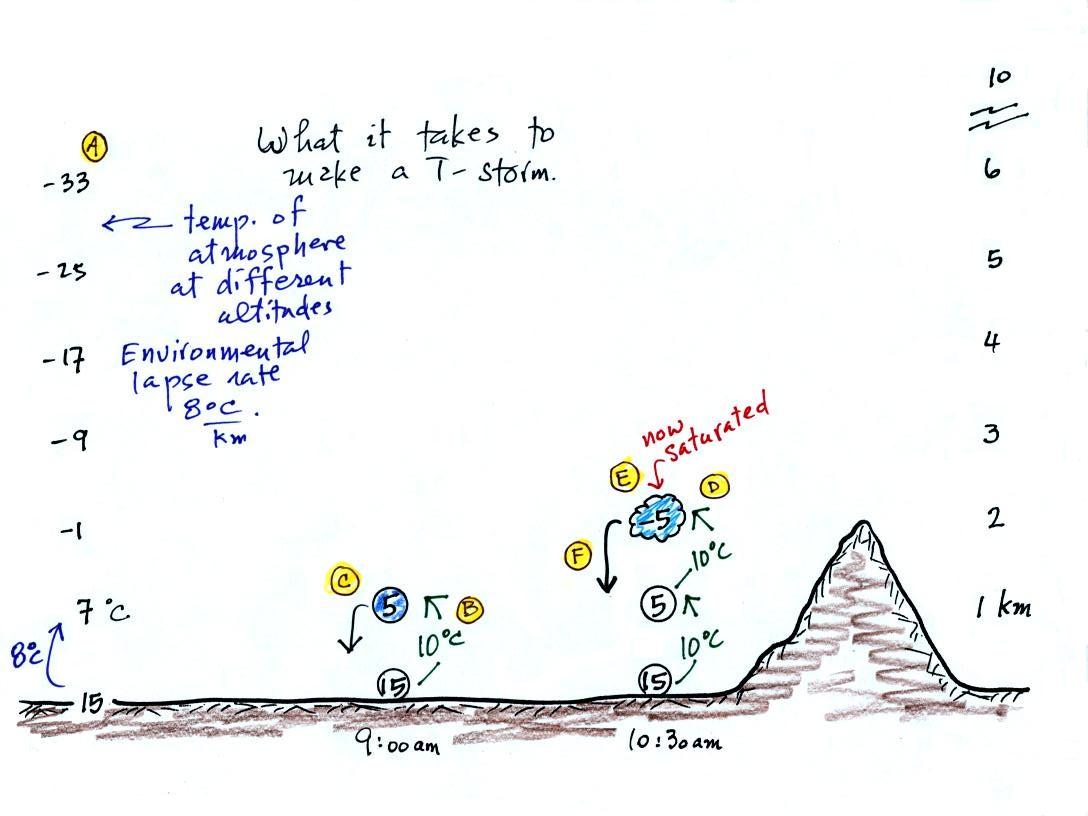

Refer back and forth between the lettered points in

the

figure

above and the commentary below.

The numbers in Column A

show the temperature of the air in the atmosphere at various altitudes

above the ground (note the altitude scale on the right edge of the

figure). On this particular day the air temperature was

decreasing at a rate of 8 C per kilometer. This rate of decrease

is referred to as the environmental lapse rate (lapse rate just means

rate of decrease with altitude). Temperature could

decrease more quickly than shown here or less rapidly.

Temperature in the atmosphere can even increase with increasing

altitude

(a temperature inversion).

At Point B, some of

the surface air is put into an imaginary container, a parcel.

Then a meterological process of some kind lifts the air to 1 km

altitude (in Arizona in the summer, sunlight heats the ground and air

in contact with the ground, the warm air becomes bouyant - that's

called free convection). The

rising air will expand and cool as it is

rising. Unsaturated (RH is less than 100%) air cools at a rate of

10 C per

kilometer. So the 15 C surface air will have a temperature of 5 C

once it arrives at 1 km altitude.

Early in the morning "Mother Nature" is only able to lift the parcel to

1 km and "then lets go." At Point C note that

the air inside the parcel is slightly colder than the air outside (5 C

inside versus 7 C outside). The air inside the parcel will be

denser than the air outside and the parcel will sink back

to the

ground.

By 10:30 am the parcel is being lifted to 2 km as shown at Point D. It is still

cooling 10 C for every kilometer of altitude gain. At 2 km, at Point E the

air

has

cooled

to

its

dew

point

temperature

and

a

cloud

has

formed. Notice at Point

F, the air in the parcel or in the cloud (-5 C) is still colder

and denser than the surrounding air (-1 C), so the air will sink back

to the ground and the cloud will disappear. Still no thunderstorm

at this point.

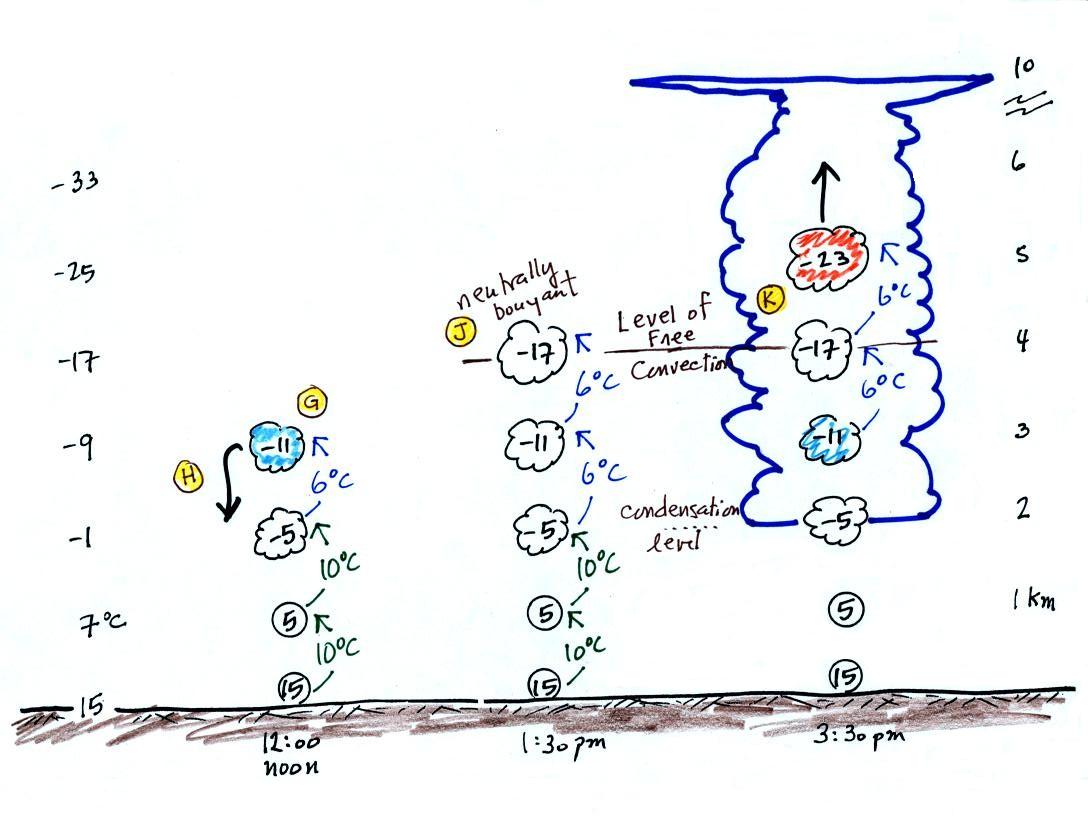

At noon, the air is lifted to 3

km. Because the

air

became saturated at 2 km, it will cool at a different rate

between 2 and

3 km altitude. It cools at a rate of 6 C/km instead of 10

C/km. The saturated air cools more slowly because release of

latent heat

during condensation offsets some of the cooling due to

expansion. The air that arrives at 3km, Point H, is again still

colder than the

surrounding air and will sink back down to the surface.

By 1:30 pm the air is getting high enough that it has become

neutrally

bouyant, it has the same temperature and density as the air around it

(-17 C inside and -17 C outside). This is called the level of

free convection, Point J in the figure.

If you can, somehow or another, lift air above the level of

free

convection it will find itself warmer and less dense than the

surrounding air as shown at Point K and will float upward to the top of

the troposphere on its own. This is really the

beginning of a thunderstorm. The thunderstorm will grow

upward

until it reaches very stable air at the bottom of the stratosphere.

This was

followed by a time lapse video tape of

actual thunderstorm formation and growth. I don't have a digital

version of that tape, so here is a

substitute time lapse of a day's worth of thunderstorm develop

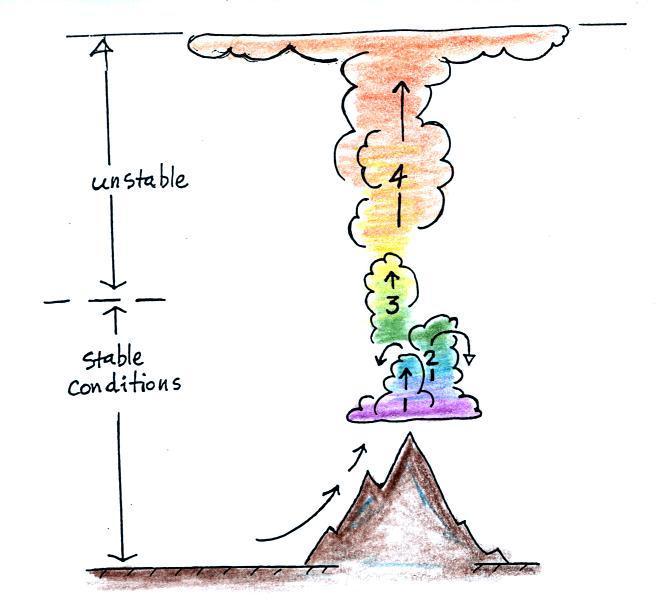

The events leading up to the initiation of a summer air mass

thunderstorm is

summarized in

the figure below. It takes

some

effort and often a good

part of the

day before a thunderstorm forms. The air must be lifted to just

above the

level of free convection (the dotted line at middle left in the

picture). Once air is lifted above the level of

free

convection it finds itself warmer and less dense that the air around it

and

floats upward on its own. I've tried to show

this with colors below. Cool colors below the level of free

convection because the air in the lifted parcel is colder and denser

than its surroundings. Warm colors above the dotted line indicate

parcel air that is

warmer and less dense than the surroudings. Once the parcel is

lifted above the level of free

convection it becomes bouyant; this is the

moment at

which the air mass thunderstorm begins.

Once a

thunderstorm develops it then goes through 3 stages.

In the

first stage you would only find updrafts inside the cloud (that's all

you need to know about this stage, you don't even need to remember its

name).

Once precipitation has formed and grown to a certain size, it will

begin to

fall and drag air downward with it. This is the beginning of the

mature

stage where you find both an updraft and a downdraft inside the

cloud.

The falling precipitation will also pull in dry air from outside the

thunderstorm (this is called entrainment). Precipitation will mix

with

this drier air and evaporate. The evaporation will strengthen the

downdraft

(the evaporation cools the air and makes it more

dense).

The thunderstorm is strongest in the mature stage. This is when

the

heaviest rain, strongest winds, and most of the lightning occur.

Eventually the downdraft spreads

horizontally throughout the inside of

the

cloud and begins to interfere with the updraft. This marks the

beginning of the end for this thunderstorm.

The

downdraft eventually fills the interior of the cloud. In this

dissipating stage you would only find weak downdrafts

throughout the cloud.

Note how the winds from one

thunderstorm can cause a region of

convergence on

one side of the original storm and can lead to the development of new

storms. Preexisting winds refers to winds that were blowing

before the

thunderstorm formed. Convergence between the prexisting and the

thunderstorm downdraft winds creates rising air that can initiate a new

thunderstorm.