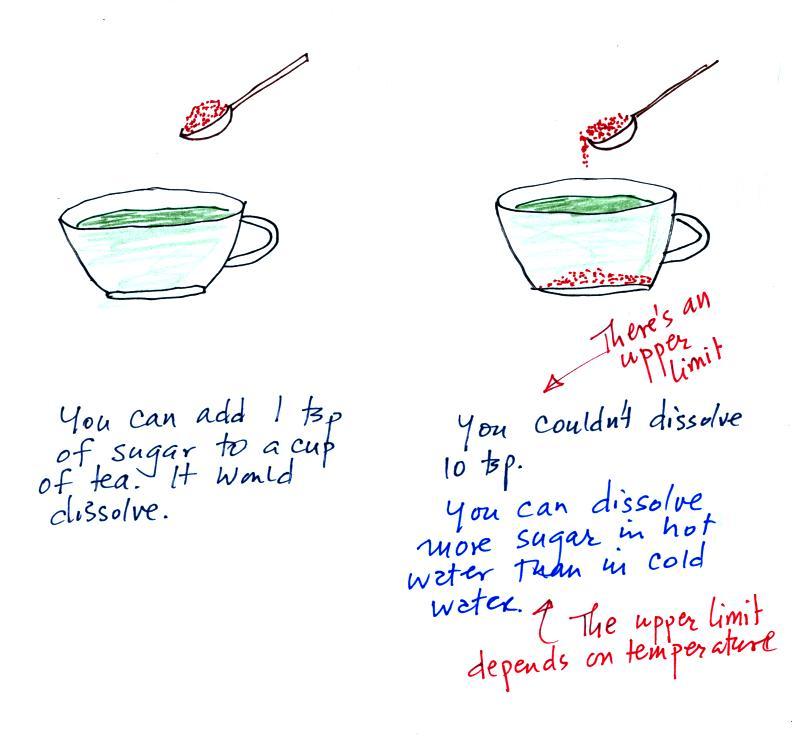

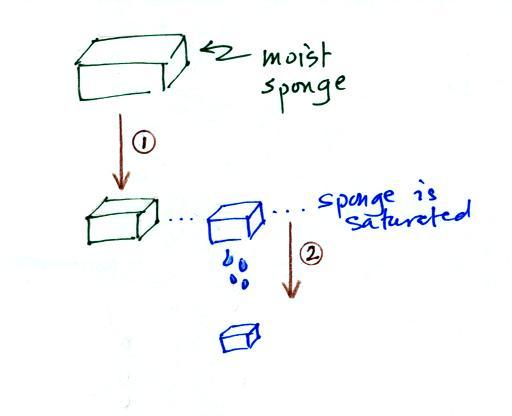

The sugar

dissolved in tea analogy is still helpful. Just as is the case

with water vapor in air, there's a limit to

how much sugar can be dissolved in a cup of hot

water. You could dissolve 1 tsp but I don't think you'd be able

to dissolve 10 tsp. You can dissolve more sugar in hot water

than in cold

water.

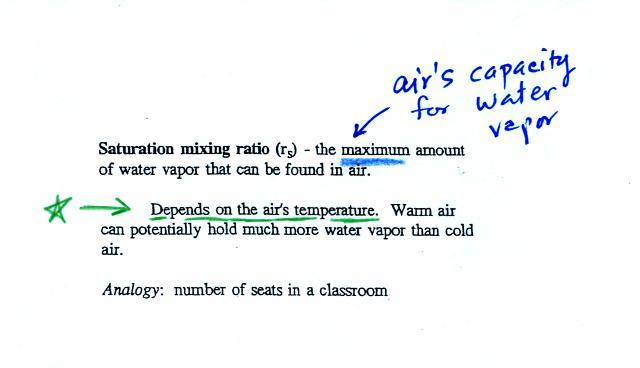

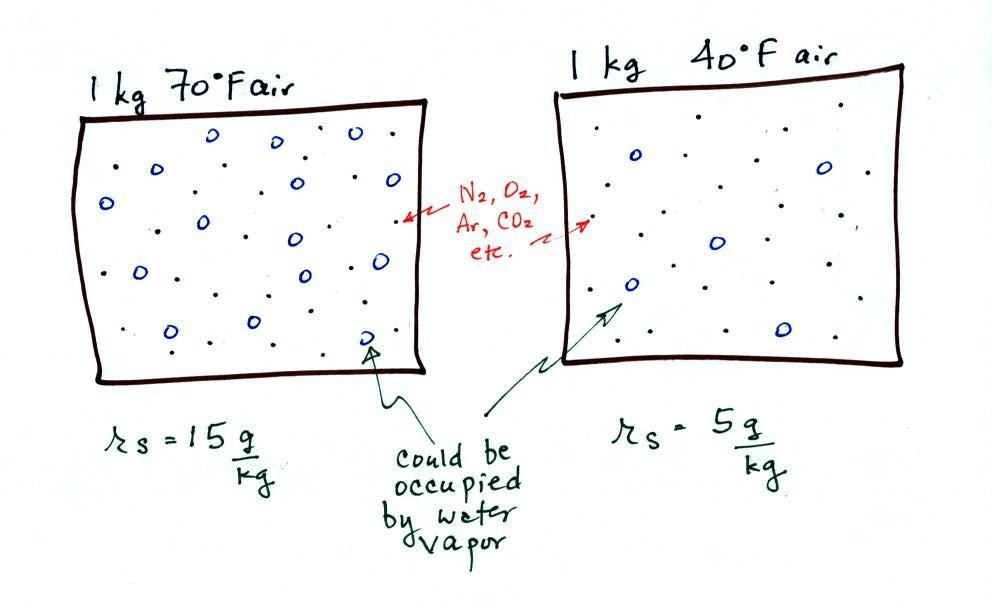

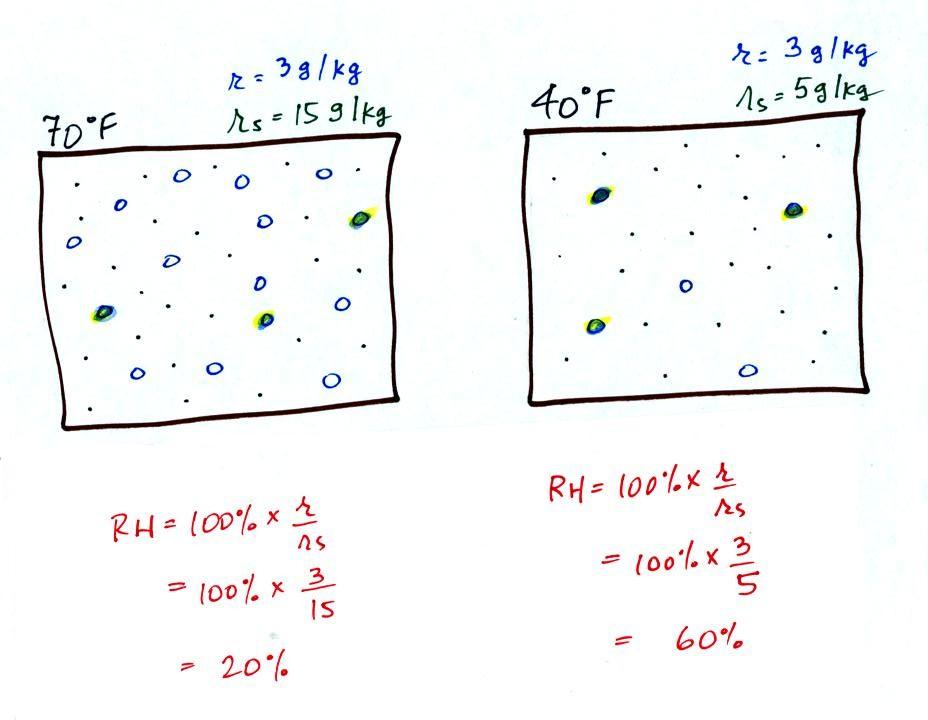

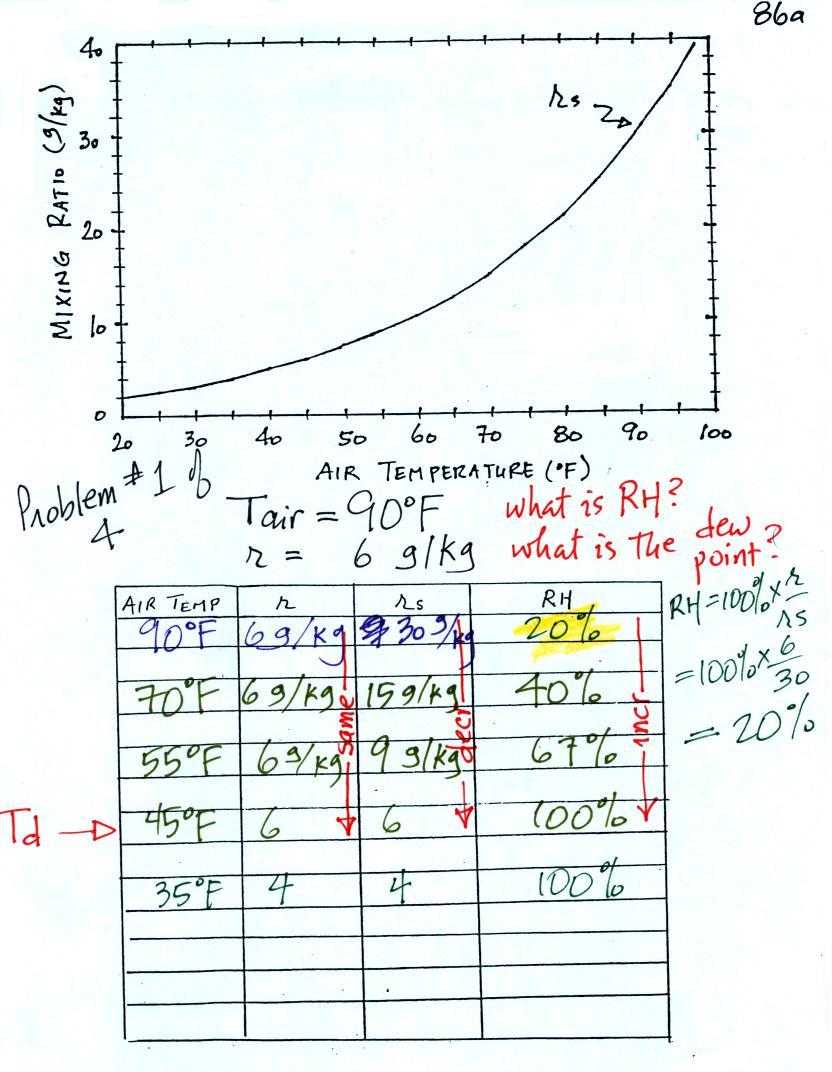

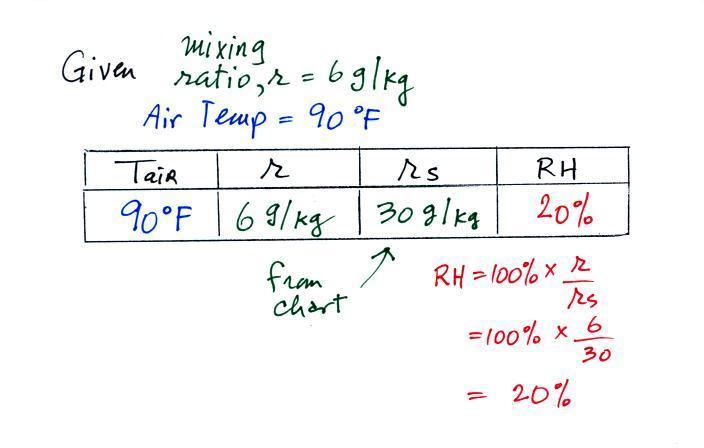

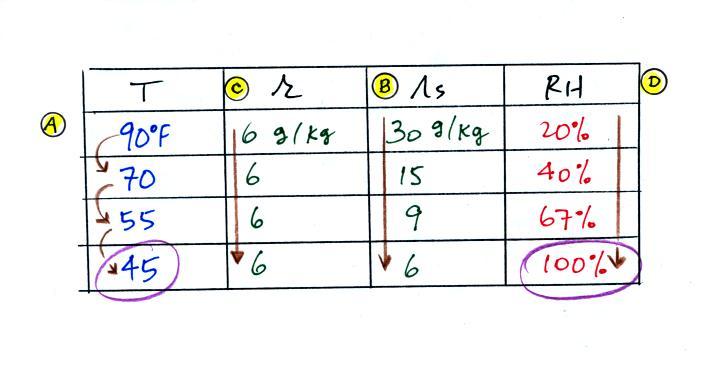

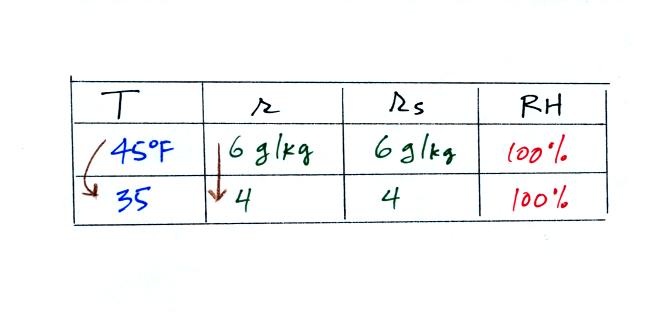

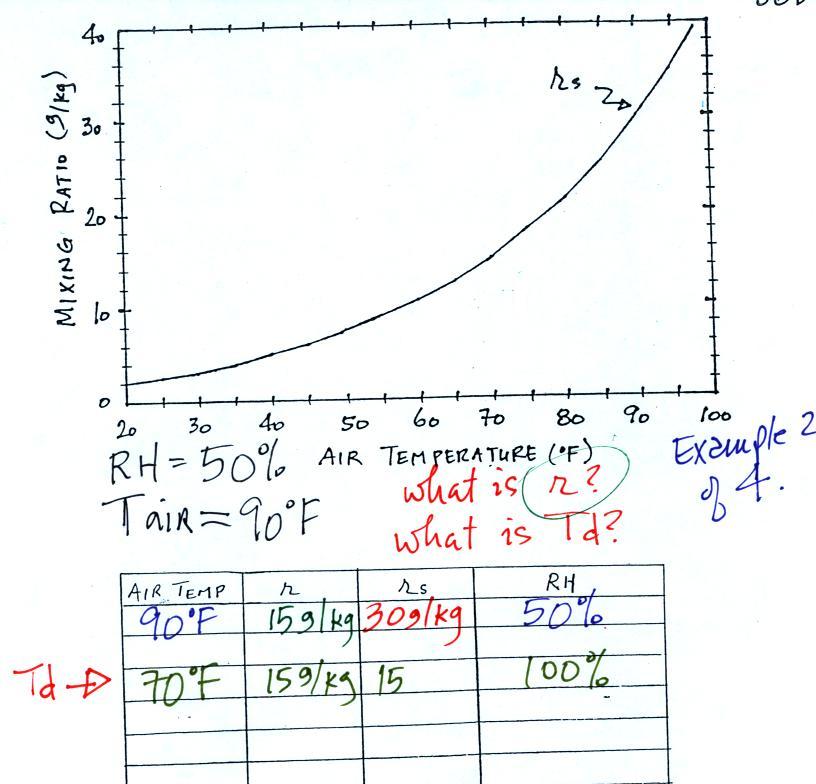

The dependence of saturation mixing ratio on air temperature is

illustrated below: