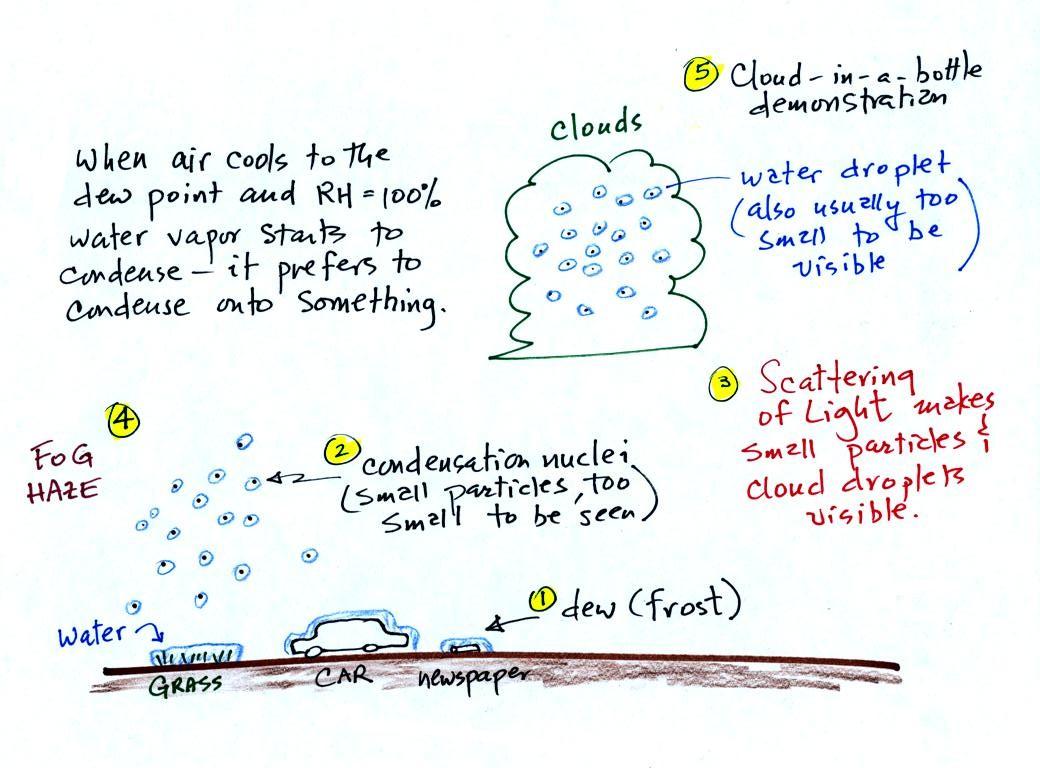

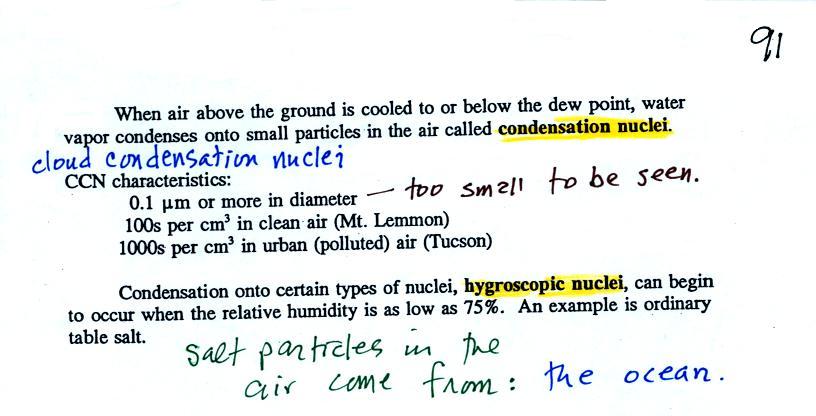

When the

relative humidity in air above the ground (and away from objects on the

ground) reaches 100%, water vapor will condense onto small particles

called condensation nuclei. It would be much harder for the water

vapor to just condense and form small droplets of pure water (you can

learn why that is so by reading the

top

of

p. 92 in the

photocopied class notes). There are always lots of CCN (cloud

condensation nuclei in the air) so this isn't an impediment to cloud

formation.

Water vapor will condense onto

certain kinds of condensation

nuclei

even when the relative humidity is below 100% (again you will find some

explanation of this on the bottom of p. 92).

These

are

called

hygroscopic

nuclei. Salt is an example; small particles of salt

mostly come from evaporating drops of ocean water.

A short homemade video (my first

actually) that showed how water

vapor would,

over time,

preferentially

condense onto small grains of salt rather than small spheres of

glass. The

figure

below

wasn't

shown

in

class.

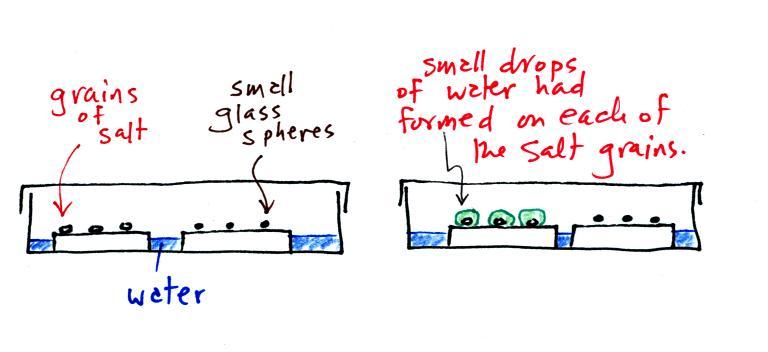

The start of the video at left

showed the small grains

of

salt were

placed on a platform in a petri dish

containing water. Some small spheres of glass were placed in the

same

dish. After about 1 hour small drops of water had formed around

each

of the grains of salt but not the glass grains (shown above at

right).

In

humid parts of the US, water will condense onto the grains of

salt

in a salt shaker causing them to stick together. Grains of rice

apparently absorb moisture which keeps this from happening and also

break up lumps of salt once they start to form. Grains of rice

might also be used because they won't fall out of the holes in the salt

shaker together with the salt. You'll find this discussed in an interesting Wikipedia

article about salt.

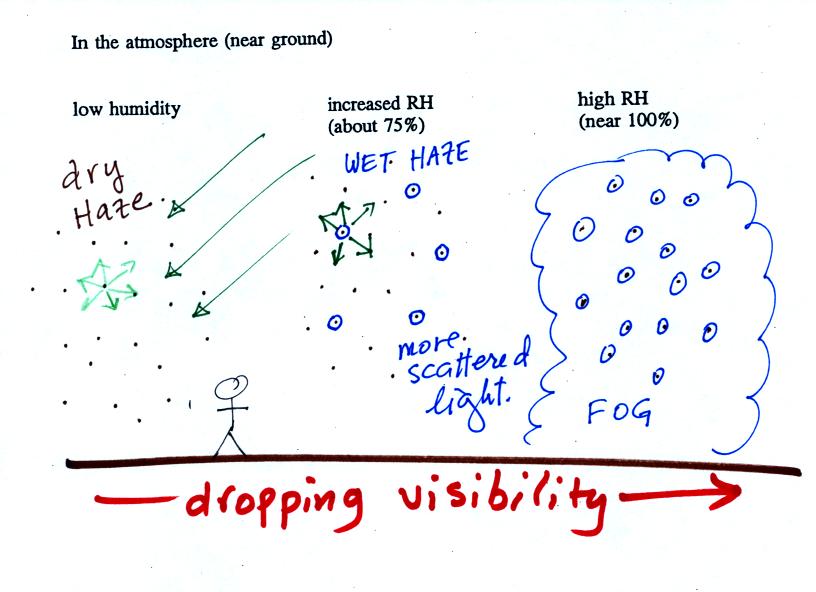

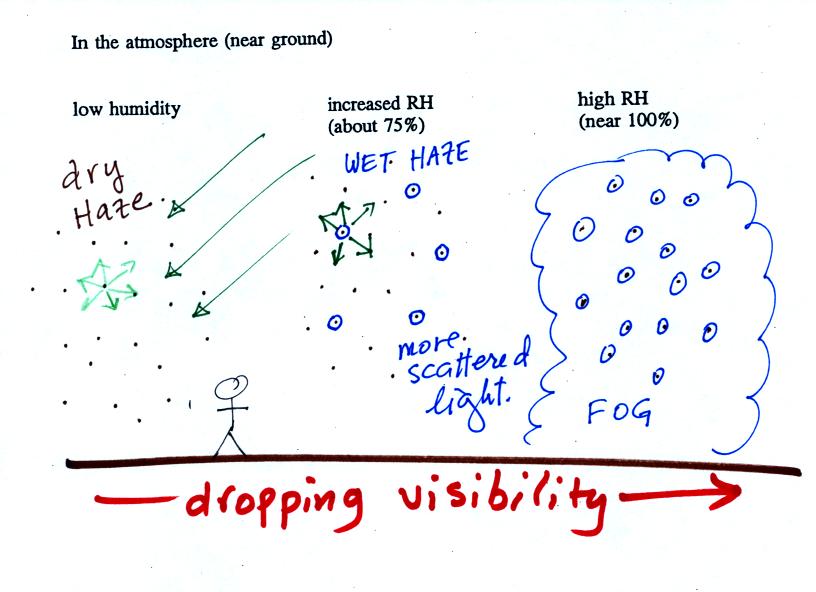

The

following figure is at the bottom of p. 91 in the ClassNotes.

This figure shows

how

cloud

condensation nuclei and increasing relative humidity can affect the

appearance of the sky and the visibility.

The air in the left most figure is relatively dry. Even

though

the condensation nuclei particles are too small to be seen with the

human eye you can tell they are there because they scatter

sunlight. When you look at the sky you see the deep blue color

caused by scattering of sunlight by air molecules mixed together with

some white

sunlight scattered by the condensation nuclei. This changes

the color of the sky from a deep blue to a bluish white

color. The more particles there are the whiter the sky

becomes. This is called "dry haze." Visibility under these

conditions might be a few tens of miles.

The middle picture shows what happens when you drive from the dry

southwestern part of the US into the humid

southeastern US or the Gulf Coast. One of the first things you

would notice is the

hazier

appearance of the air and a decrease in visibility. Because the

relative humidity is high,

water vapor begins to condense onto some of the condensation nuclei

particles (the hygroscopic nuclei) in the air and forms small water

droplets. The water droplets scatter more sunlight than just

small particles alone. The increase in the amount of scattered

light is what gives the air its hazier appearance. This is called "wet

haze." Visibility now might now only be a few miles.

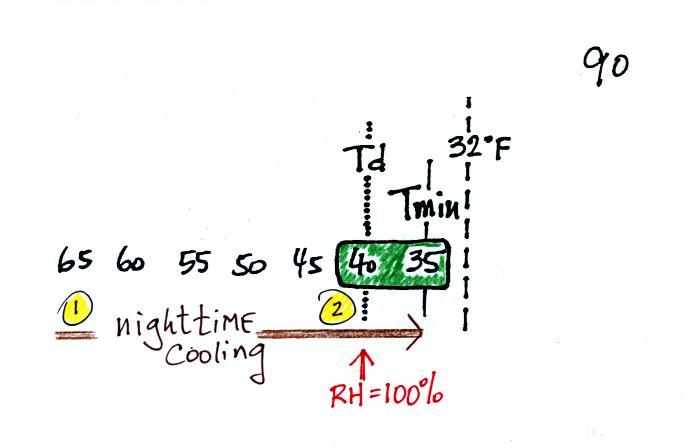

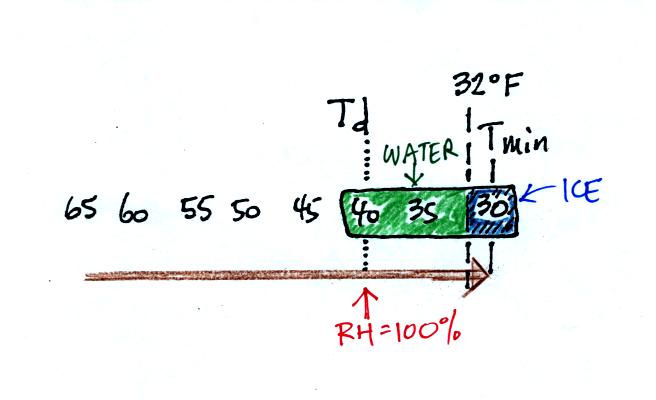

Finally when the relative humidity increases to 100% fog

forms.

Fog can cause a severe drop in the visibility. The thickest fog

forms in dirty air that contains lots of condensation nuclei.

That is part of the reason the Great London Smog of 1952 was so

impressive. Visibility was at times just a few feet! We

could see this effect in the cloud-in-a-bottle demonstration that was

performed next.

Cooling air, changing relative humidity, condensation

nuclei, and scattering of

light are all involved in this demonstration.

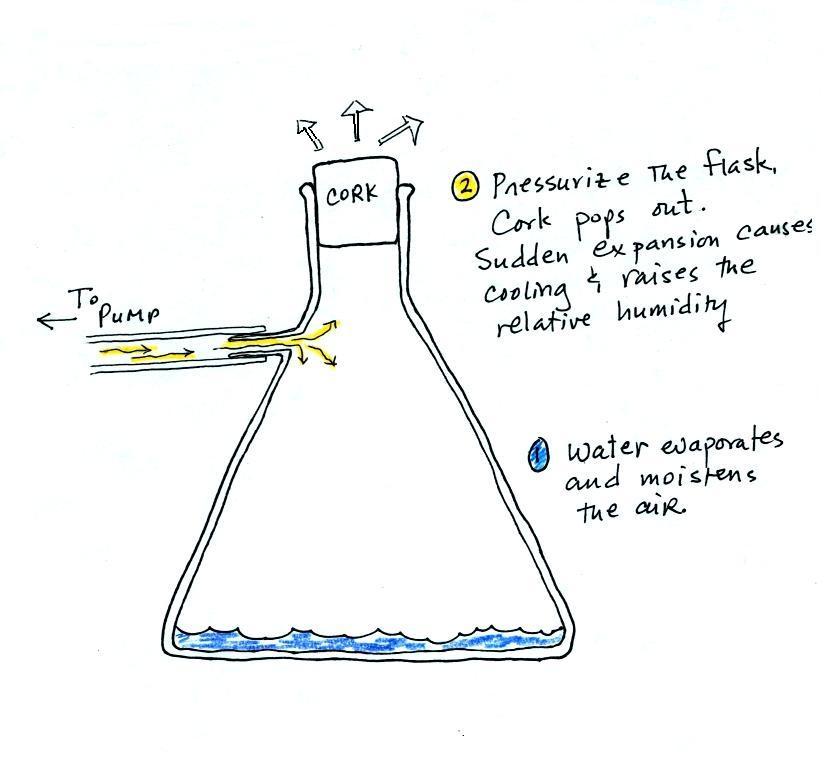

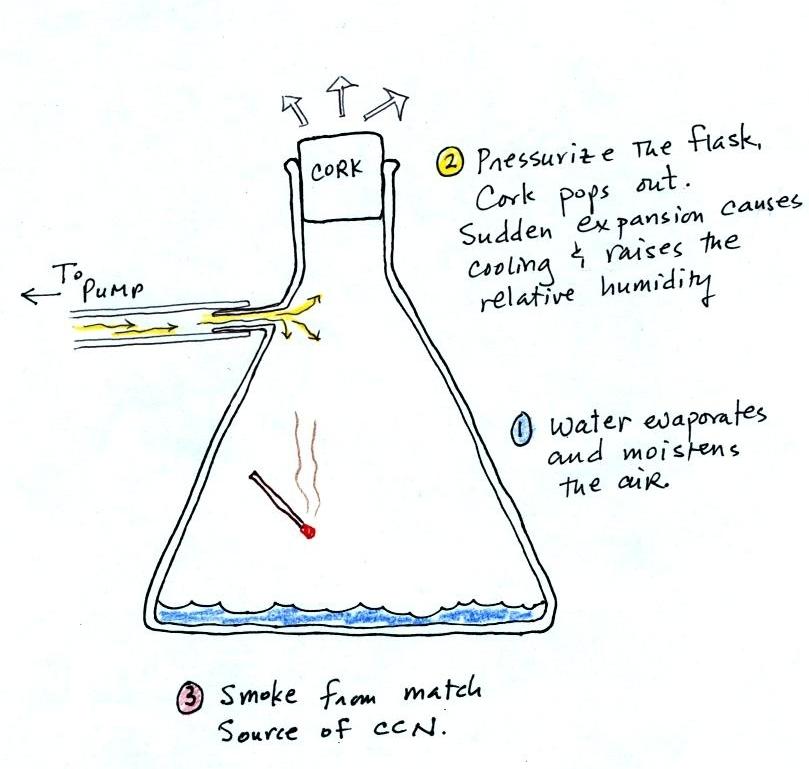

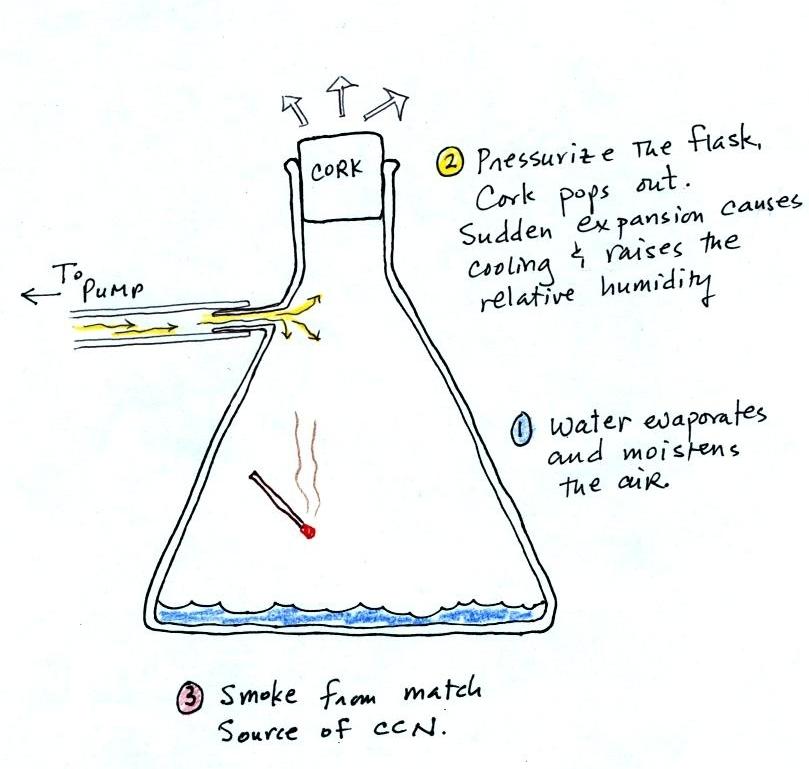

We used my backup flask in class. Normally I use use a

strong, thick-walled, 4 liter vacuum flask (designed to not implode

when all of the air is pumped out

of them, they aren't designed to not explode when pressurized).

There

was a little

water in the bottom of the flask to moisten the air in the flask.

Next we pressurized the air in the flask with a bicycle pump. At

some point the

pressure blows the cork out of the top of the flask.

The air in

the flask expands outward and cools. This sudden cooling

increases the

relative humidity of the moist air in the flask to 100% ( probably more

than 100% momentarily ) and water vapor condenses onto cloud

condensation nuclei in

the air. A very faint cloud became visible at this point.

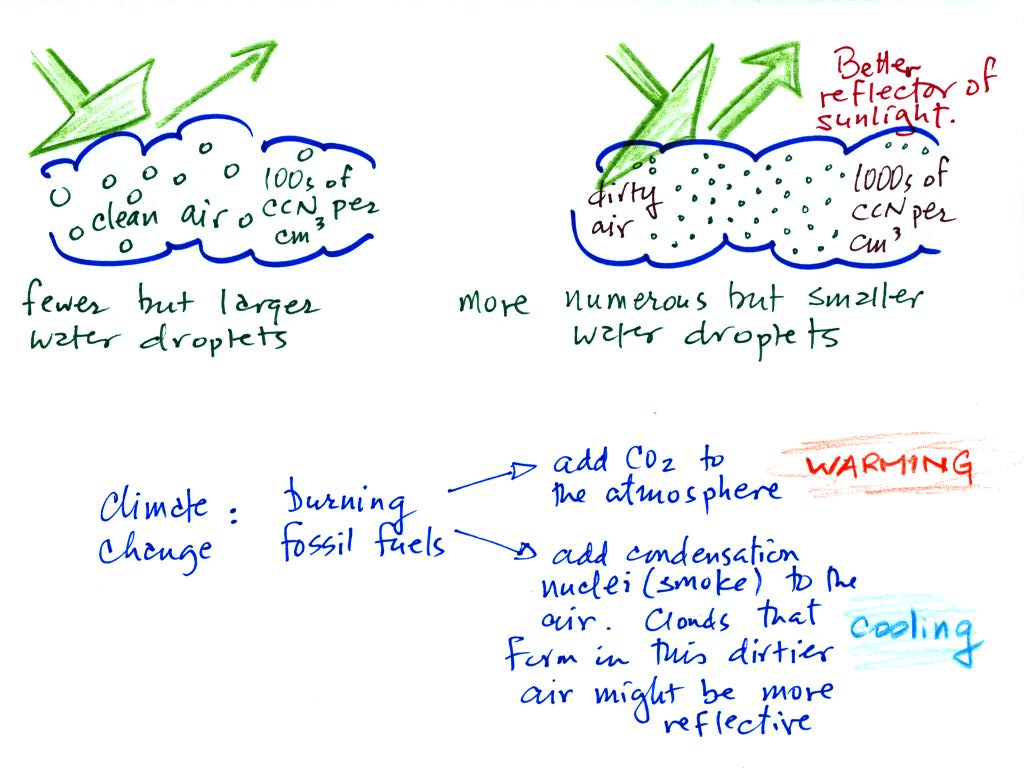

This effect has some implications for climate change.

A cloud that forms in dirty air is composed of a large

number of small droplets (right figure above). This cloud is more

reflective

than a cloud that forms in clean air, that is composed of a smaller

number of larger

droplets (left figure).

Combustion of fossil fuels adds carbon dioxide to the atmosphere.

There is concern that increasing carbon dioxide concentrations (and

other greenhouse gases) will

enhance the greenhouse effect and cause global warming.

Combustion also adds condensation nuclei to the atmosphere (just like

the burning match added smoke to the air in the flask). More

condensation nuclei might make it easier for clouds to form, might make

the clouds more reflective, and might cause cooling. There is

still quite a bit of uncertainty about how clouds might change and how

this

might affect climate. Remember that clouds are good absorbers of

IR radiation and also emit IR radiation.

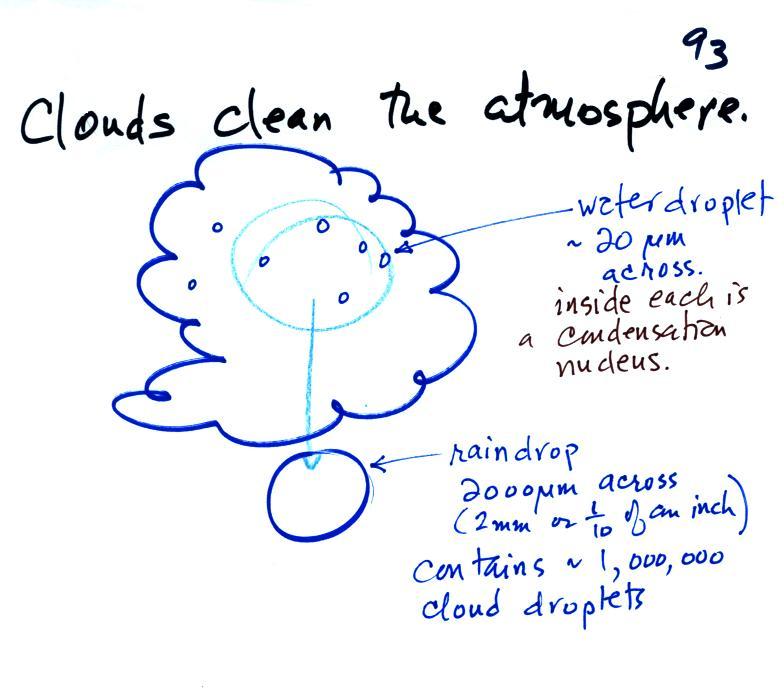

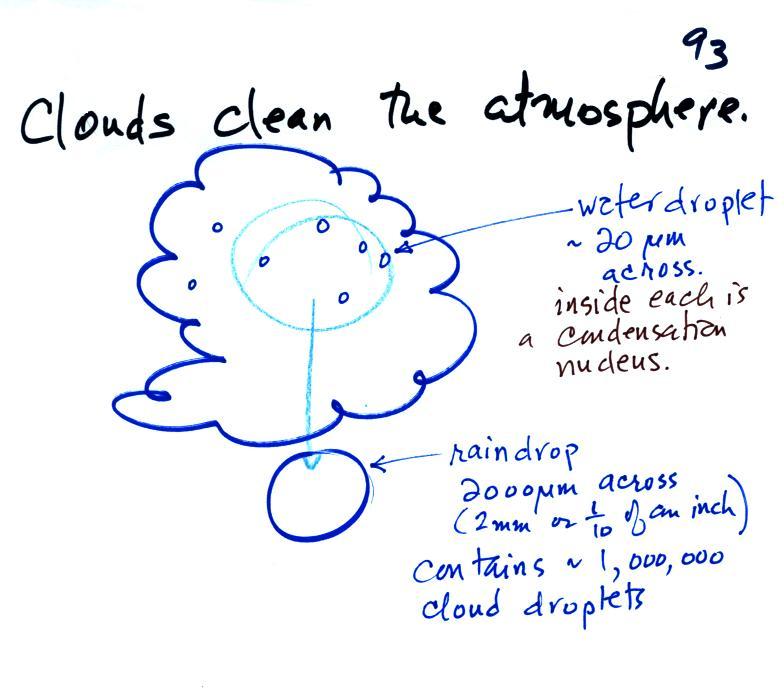

Clouds are

one of

the best ways of cleaning the atmosphere

A cloud is composed of small water

droplets (diameters of 10 or 20

micrometers) that form on particles ( diameters of perhaps 0.1 or 0.2

micrometers). The droplets "clump"

together to form a

raindrop (diameters of 1000 or 2000 micrometers which is 1 or 2

millimeters), and the raindrop carries the particles to the

ground.

A typical raindrop can contain 1 million cloud droplets so a single

raindrop

can remove a lot of particles from the air. You may have noticed

how clear the air seems the day after a rainstorm; distant mountains

are crystal clear and the sky has a deep blue color. Gaseous

pollutants can dissolve in the water droplets and be carried to

the ground by rainfall also. We'll be looking at the formation of

precipitation later this week.