We weren't done

yet. We had a little time to get started on a new topic, the

ideal gas

law. This is a first step in really

understanding why warm air rises and cold air sinks.

Hot air balloons rise (they also

sink), so does the relatively

warm air in a thunderstorm updraft (it's warmer than the air around

it). Conversely cold air sinks. The surface winds

caused by a thunderstorm downdraft (as shown above) can reach speeds of

100 MPH (stronger than many tornadoes) and are a serious weather hazard.

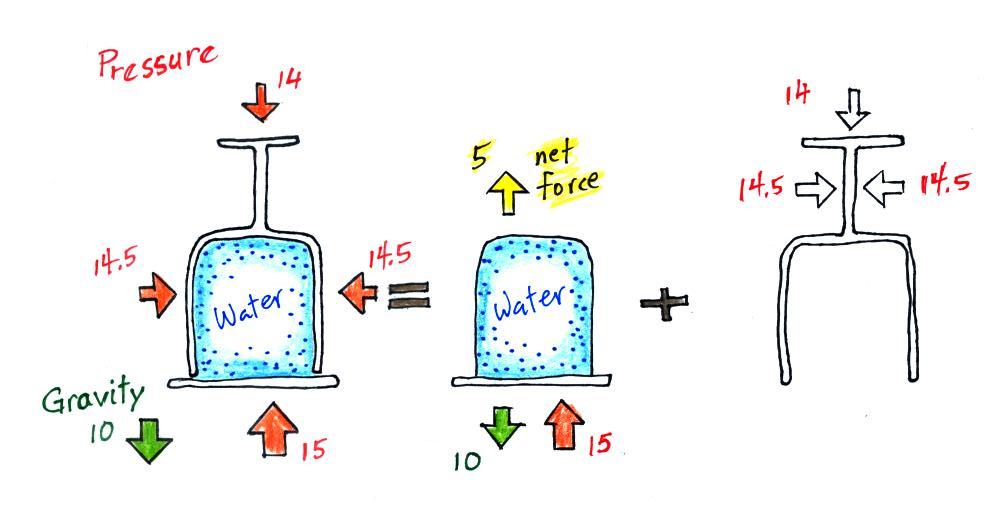

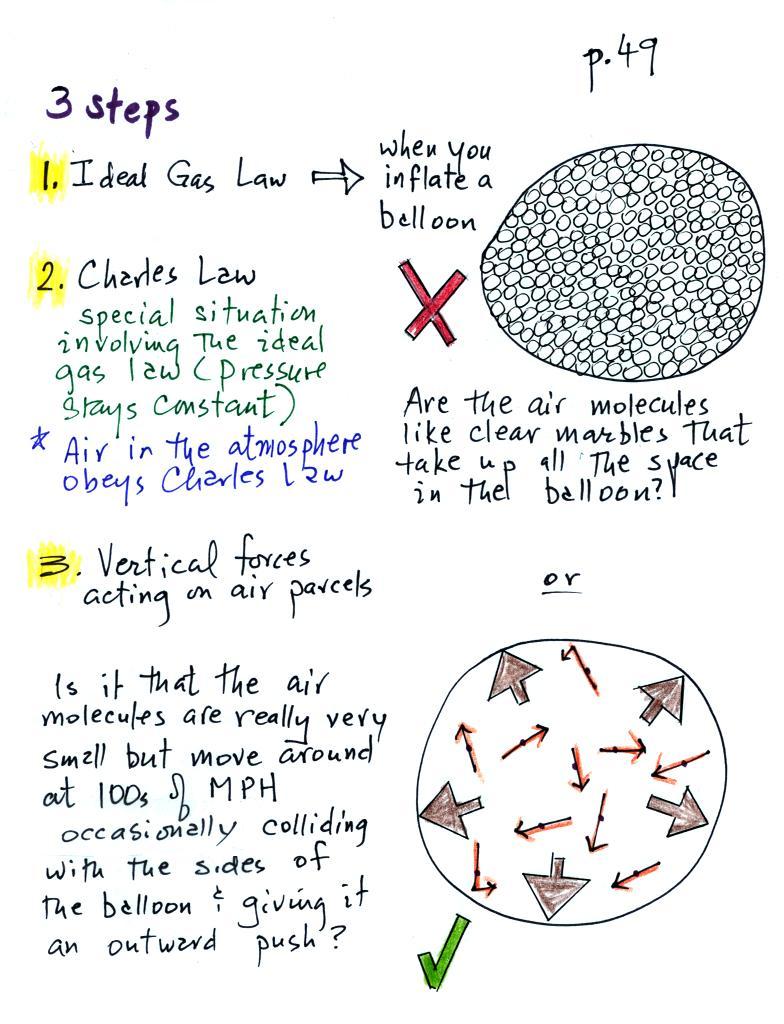

A full understanding of these rising and sinking

motions is

a

3-step process (the following is

from the bottom part of p. 49 in the photocopied ClassNotes). We

only had time to look at the first step today.

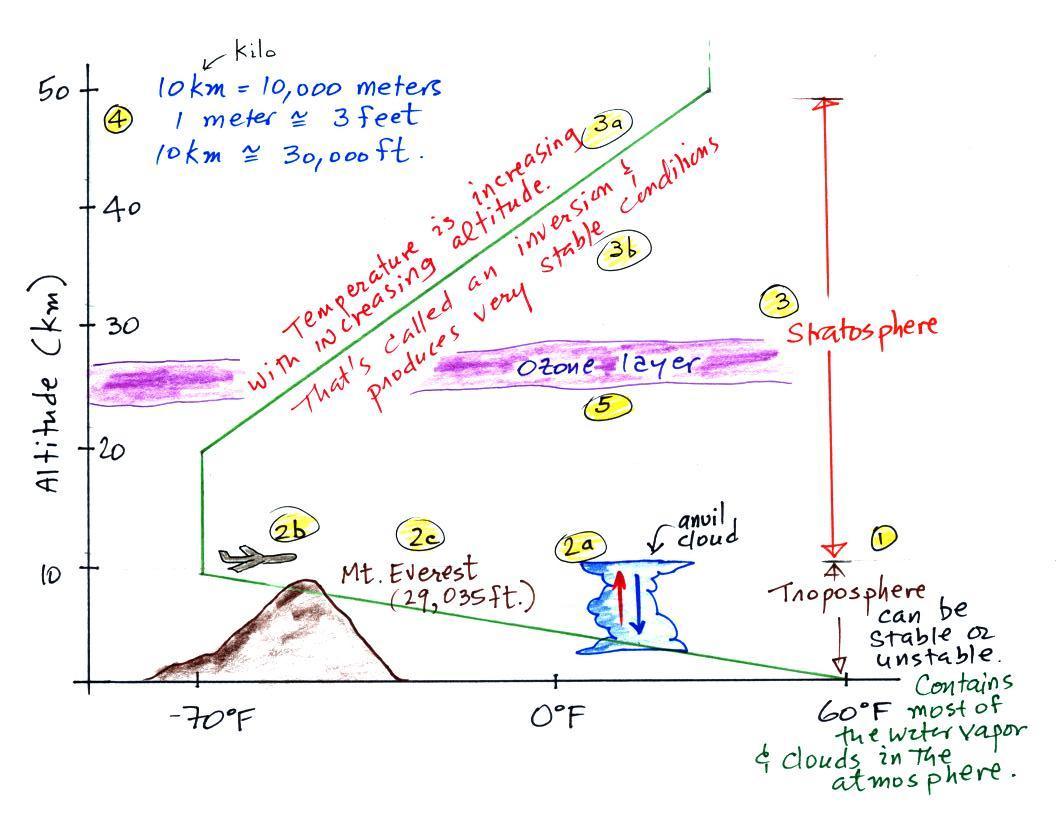

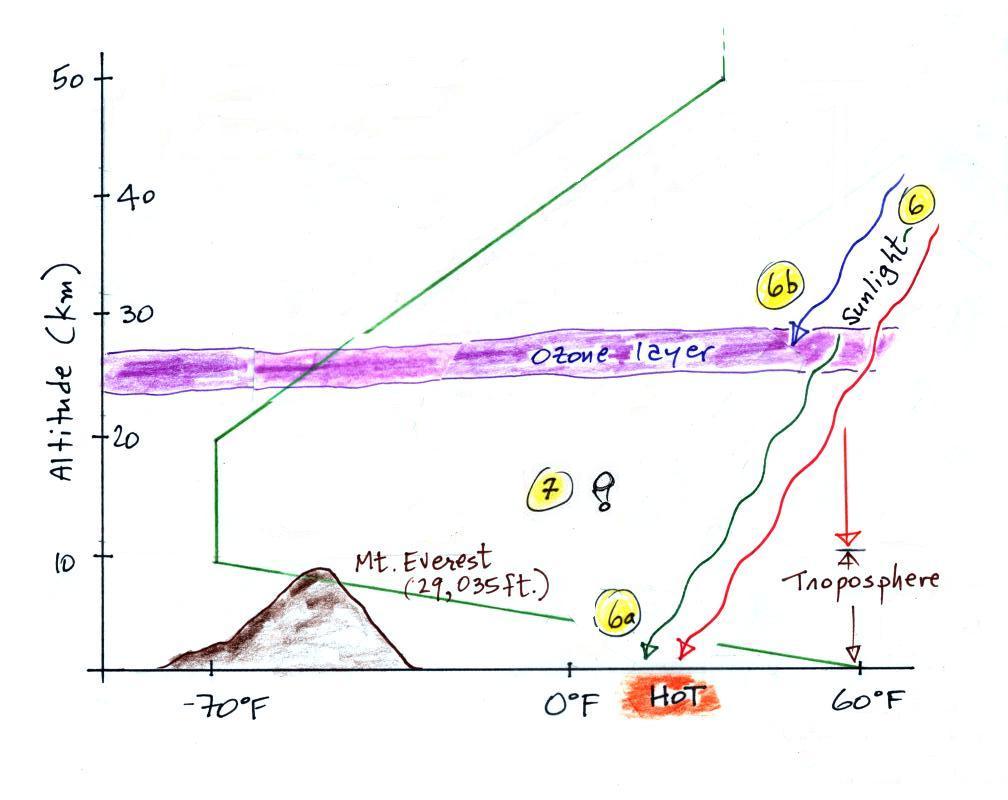

We will first learn about the ideal

gas law. That is an equation that tells you which properties of

the air

inside a

balloon work to determine the air's pressure. Then we will look

at Charles' Law, a special situation involving the ideal gas law (air

temperature and density change together in a way that keeps the

pressure

inside a balloon constant).

Then we'll learn about the

vertical forces that act on air (an upward

and a downward force).

Students working on Experiment #1 will need to understand the

ideal gas law to be able to fully explain why/how their experiment

works.

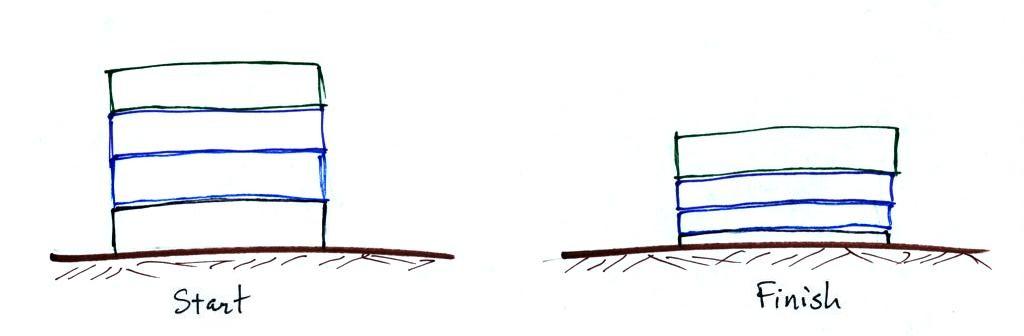

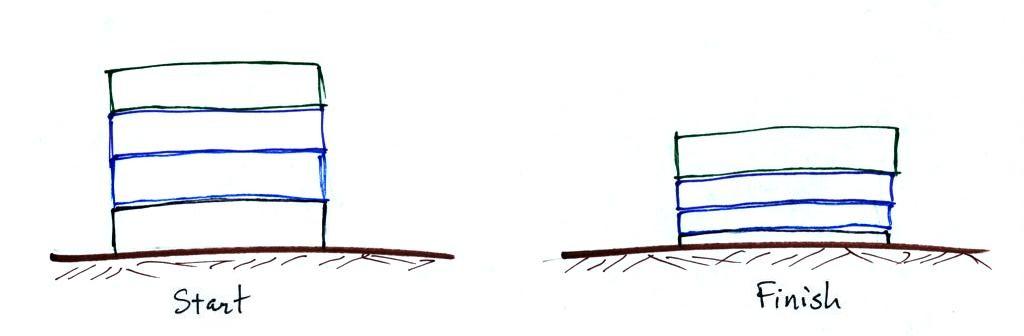

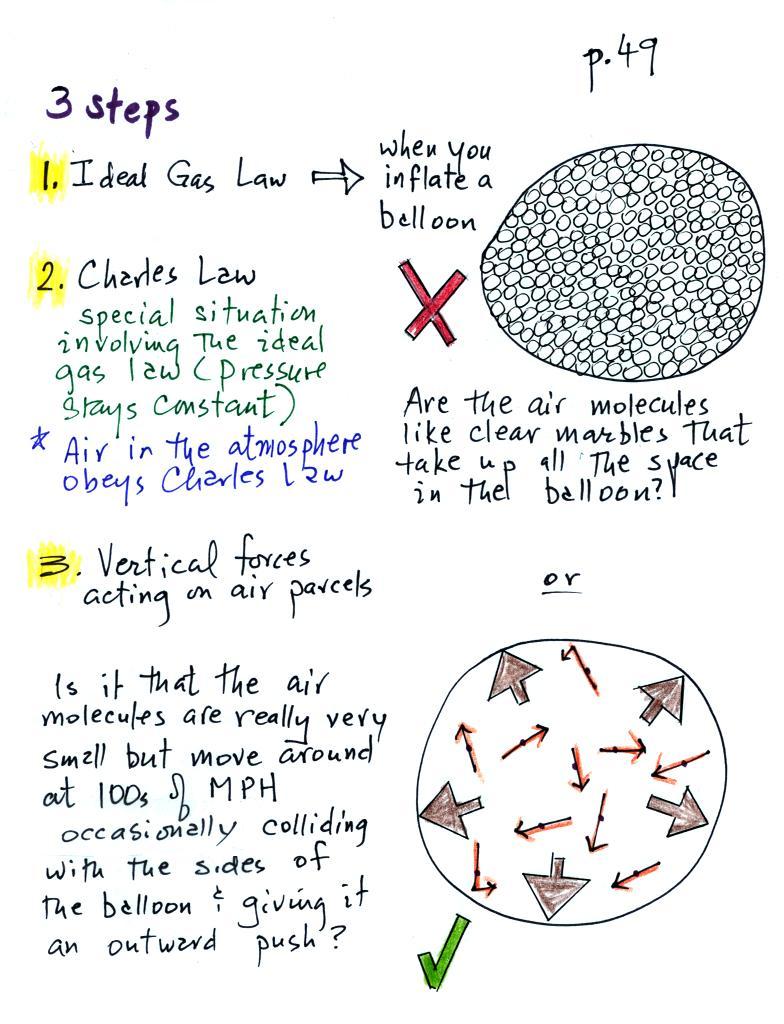

The figure above makes an important point: the air molecules in a

balloon "filled with air" really take up very little space. A

balloon filled with air is mostly empty space. It is the

collisions of air molecules traveling at 100s of miles per hour with

the inside walls of the balloon

that keep it inflated.

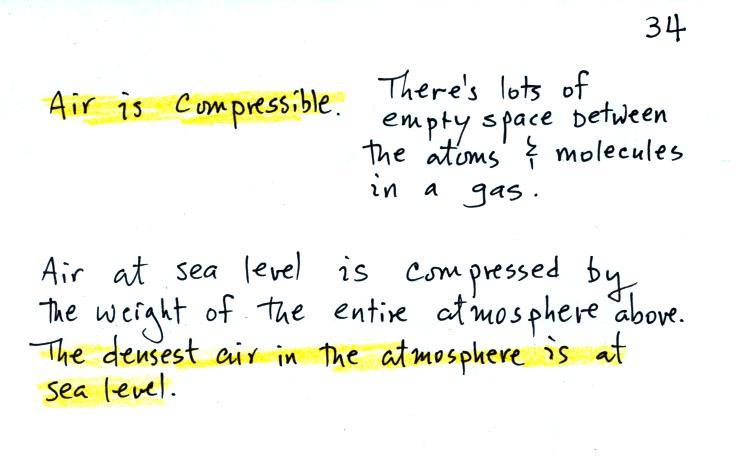

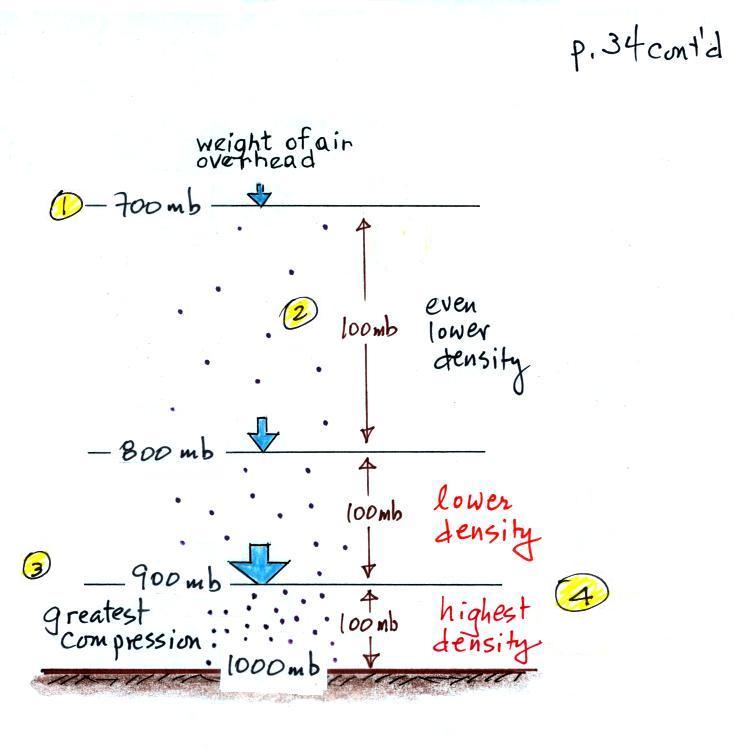

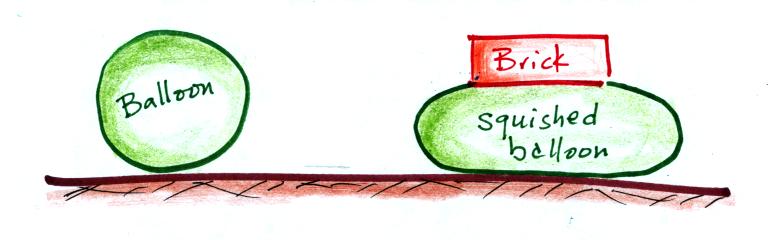

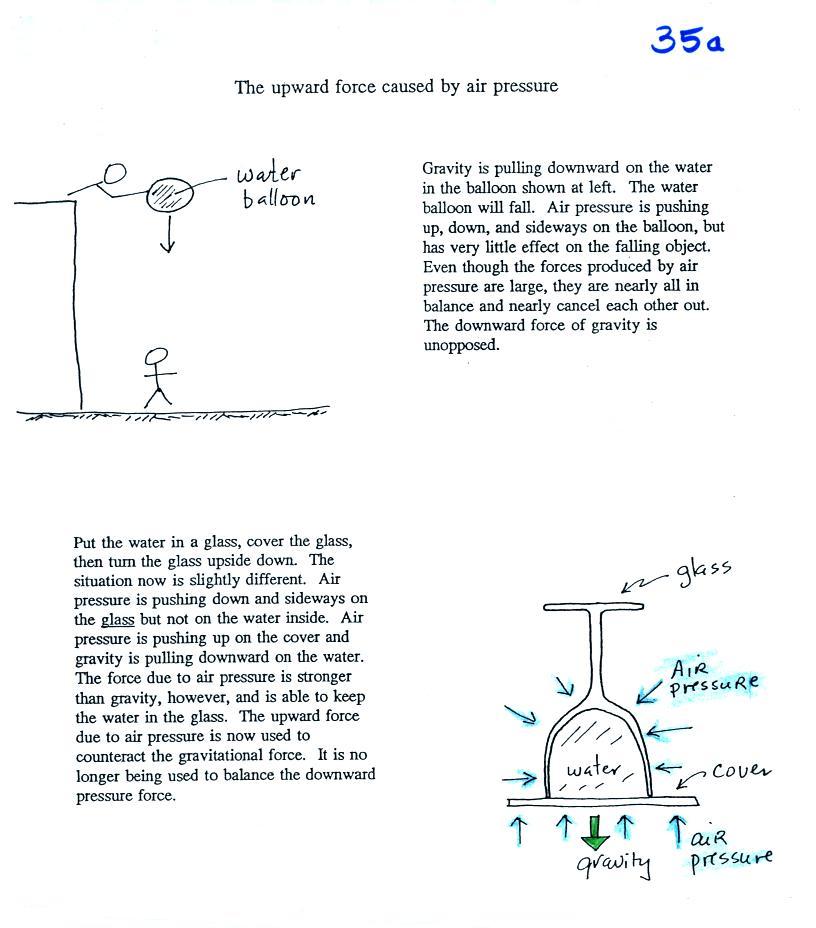

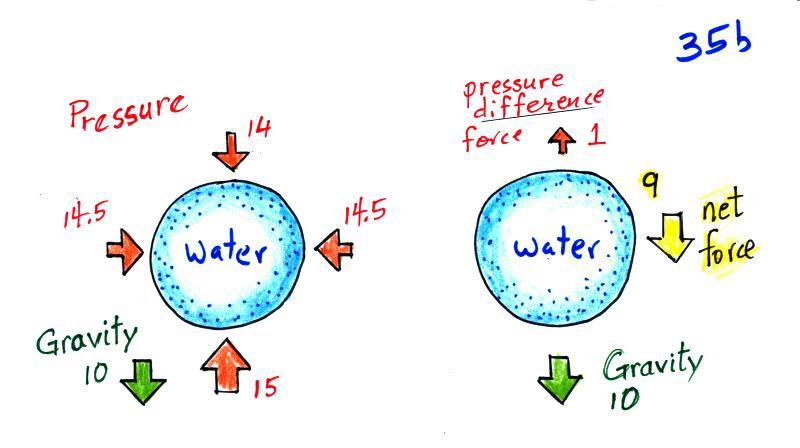

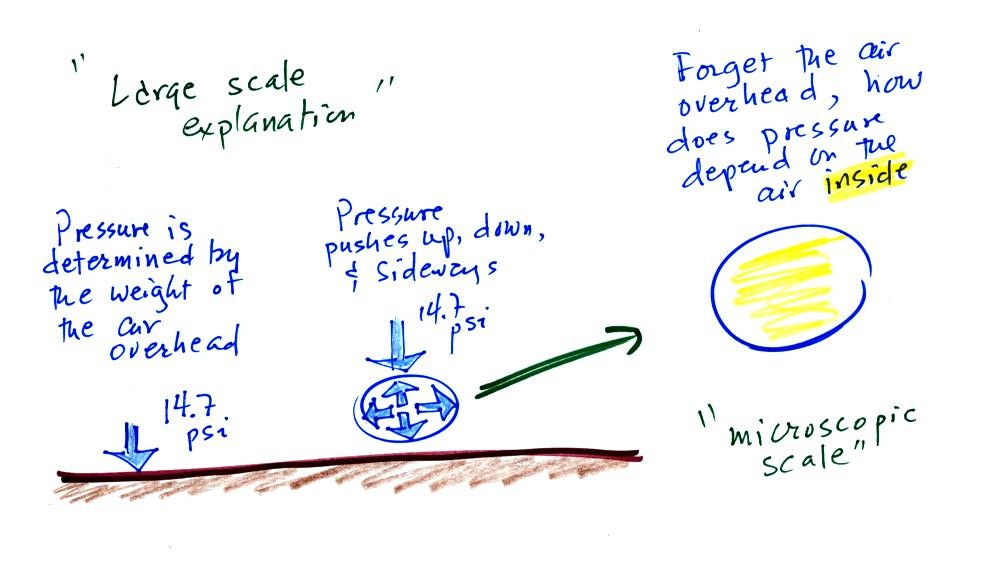

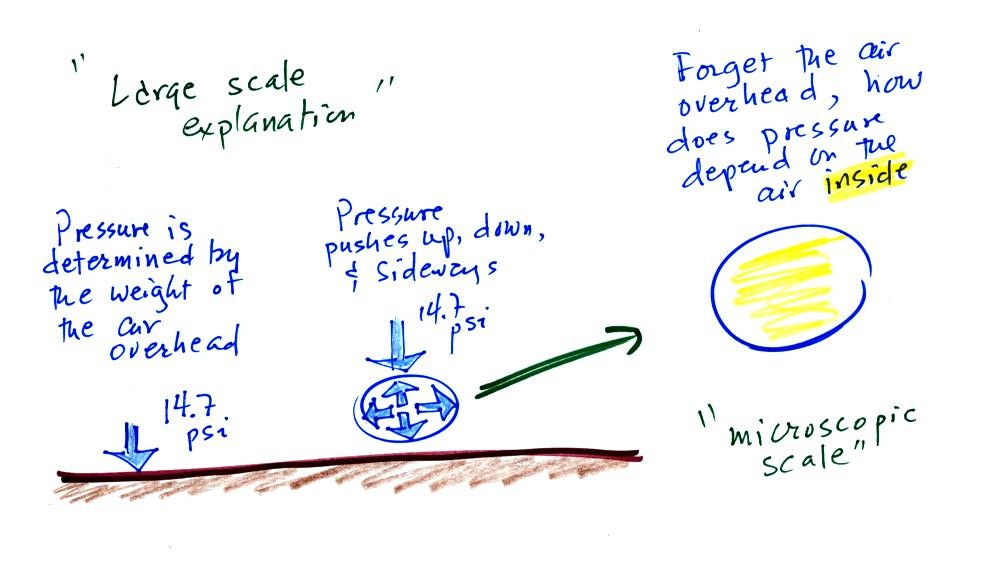

Up to this

point in the semester we

have been thinking of pressure as

being determined

by the weight of the air overhead. Air pressure pushes down

against the ground at sea level with 14.7 pounds of force per square

inch. If you imagine the weight of the atmosphere pushing down on

a balloon sitting on the ground you realize that the air in the balloon

pushes back with the same force. Air everywhere in the atmosphere

pushes upwards, downwards, and sideways.

The ideal gas law

equation is another way of thinking about air pressure, sort of a

microscopic scale version. We ignore

the atmosphere and concentrate on just the air inside the

balloon. We'll end up with an equation. Pressure (P)

will be on the left hand side of the equation. Relevant

properties of the air

inside the

balloon will be found on the right hand side.

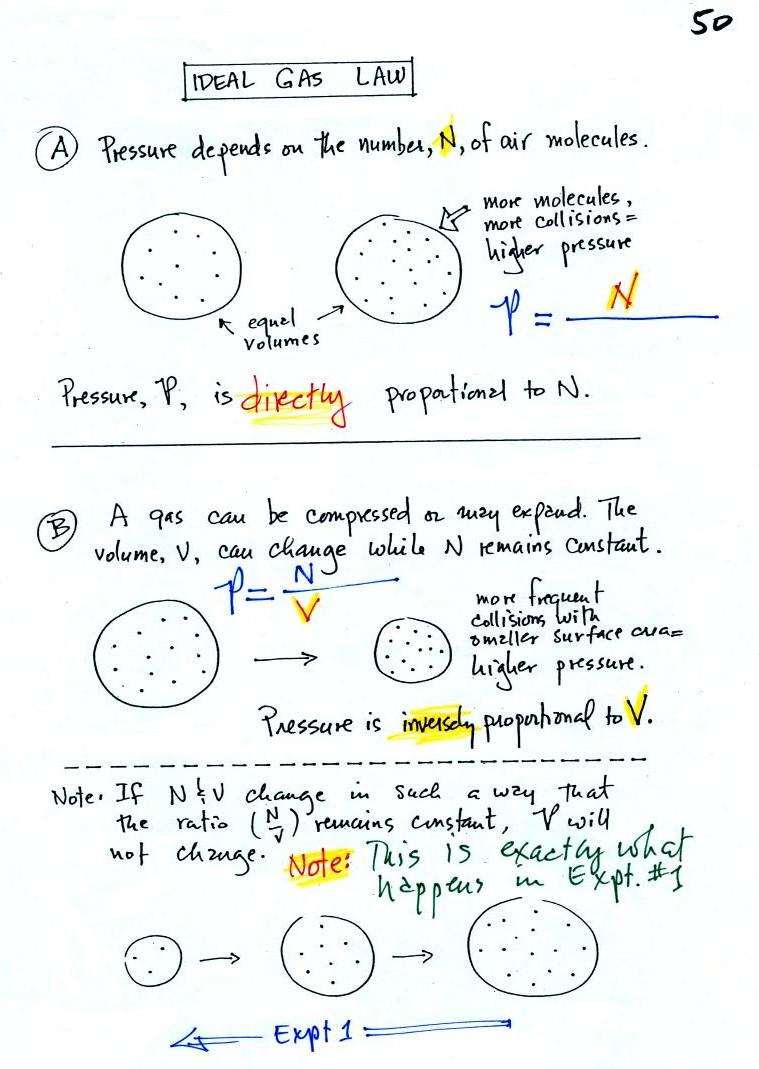

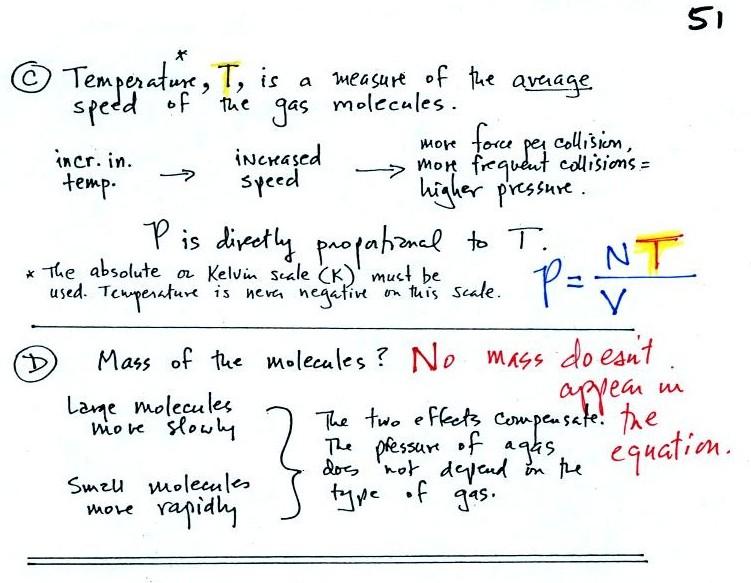

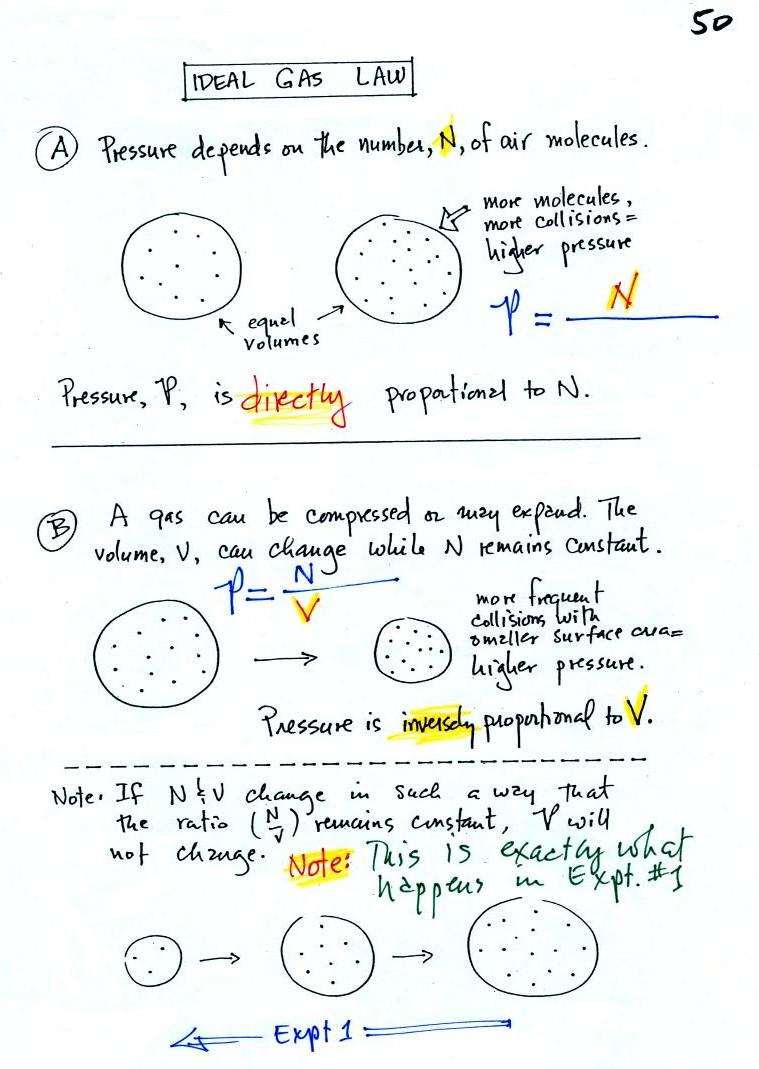

In A

the pressure produced by

the air

molecules inside a balloon will

first depend on how many air molecules are there, N. If there

weren't any air molecules at all there wouldn't be any

pressure. As you add more and more add to something like a

bicycle tire, the

pressure increases. Pressure is directly proportional to N; an

increase in N causes an increase in P. If N doubles, P also

doubles (as long as the other variables in the equation don't change).

In B

air pressure inside a balloon

also

depends on the size of the

balloon. Pressure is inversely proportional to volume, V

. If V were to double, P would drop to 1/2 its original value.

Note

it

is possible to keep pressure constant by changing N and V

together in just the right kind of way. This is what happens in

Experiment #1 that some students are working on. Here's a little

more detailed look at that experiment.

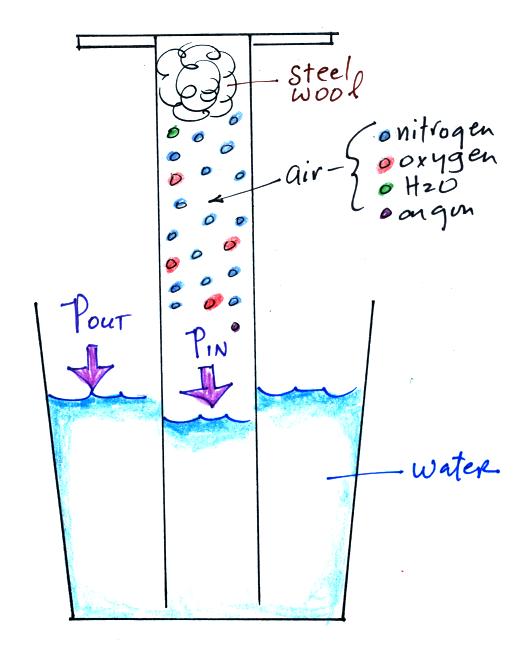

An air sample is trapped together with some steel wool inside a

graduated cylinder. The cylinder is turned upside down and the

open end is stuck into a glass of water. This is shown at left

above. Water will move into or out of the cylinder to keep Pout

equal to Pin. We assume

that neither

of

these pressures changes during the experiment. In this

experiment pressure is constant.

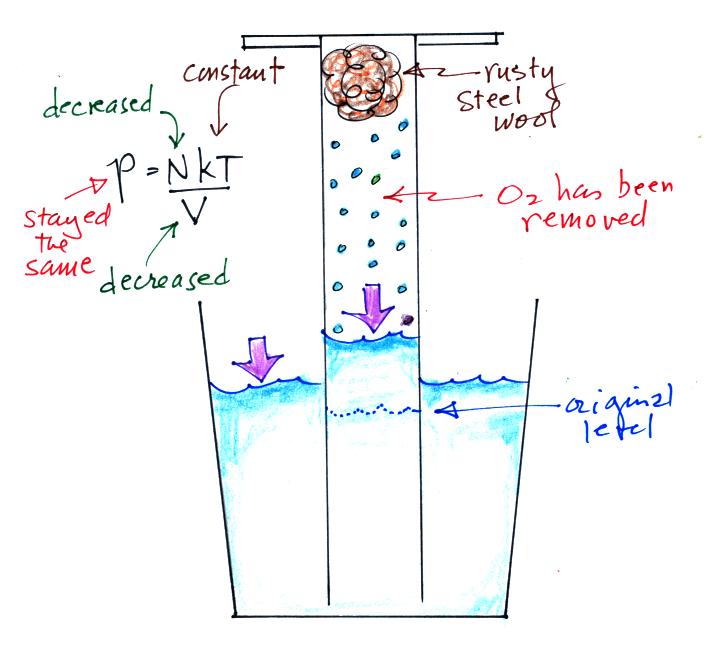

Oxygen in the cylinder reacts with steel wool to form rust.

Oxygen is

removed from the air sample which causes N (the total number of air

molecules) to decrease. Removal of oxygen would ordinarily cause

a drop in Pin.

But,

as

oxygen

is

removed,

water

rises

up

into

the

cylinder decreasing the air sample

volume. N and V both decrease in the same relative amounts and

the air sample pressure remains constant.

If you were to remove 20% of the air molecules, V would decrease

to 20% of its original value and pressure would stay constant. It

is the change in V that you can measure and use to determine the oxygen

percentage concentration in air.

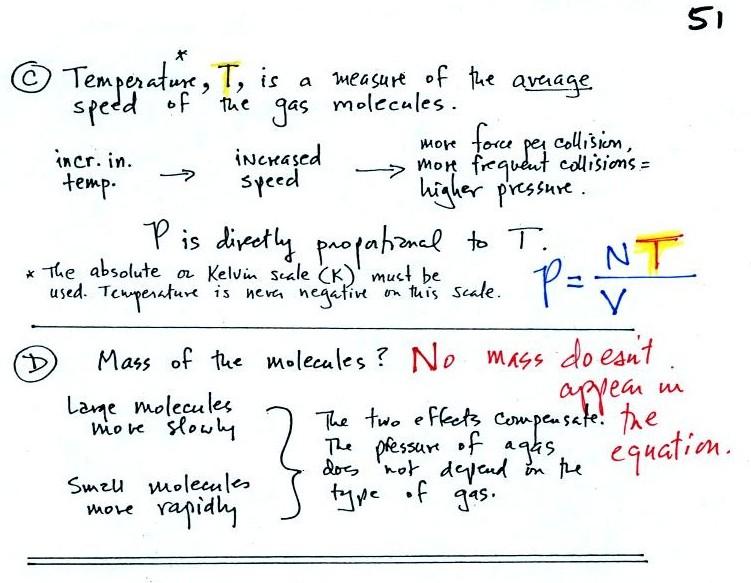

Part C: Increasing

the temperature of the gas in a balloon will cause the gas molecules to

move more quickly. They'll collide with the walls of the balloon

more frequently and rebound with greater force. Both will

increase the pressure. You shouldn't throw a can of spray paint

into a fire because the temperature will cause the pressure inside the

can to increase and the can could explode.

Surprisingly, as explained in Part

D,

the pressure

does

not depend on the mass of the

molecules. Pressure doesn't depend on the composition of the

gas. Gas molecules with a lot of mass will move slowly, the less

massive molecules will move more quickly. They both will collide

with the walls of the container with the same force.

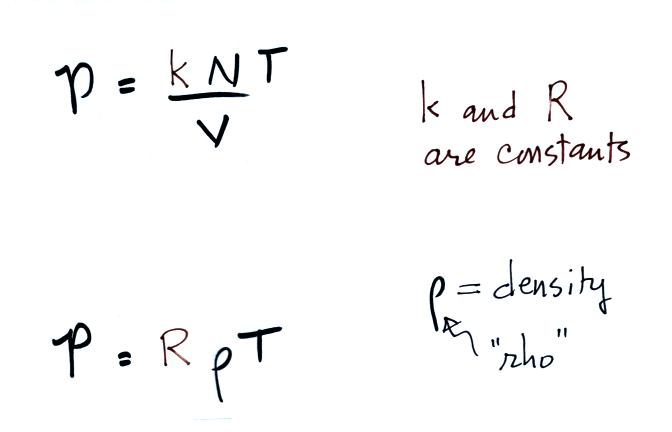

The figure below (which replaces the bottom of p. 51 in the

photocopied

ClassNotes) shows two forms of the ideal gas law. The top

equation is the one we just derived and the bottom is a second slightly

different version. You can

ignore the

constants k and R if you are just trying to understand how a change in

one of the variables would affect the pressure. You only need the

constants when you are doing a calculation involving numbers (which we

won't be doing).

We'll come back to this topic and

make use of these equation in class on Thursday. I also mentioned

that if someone reminds me, I'll put both equations on the board for

you to use during the next quiz.