Thu., Sept. 27, 2012

click here to

download these notes in a more printer friendly format

A couple of songs from Playing for Change. The first was Don't Worry

and was followed by the best version of Stand By Me

you'll ever hear (that's my opinion anyway).

The Experiment #1 reports have all been graded and were returned

in class today. You now have two weeks to revise your report if

you want to (you don't have to). You only need to change sections

were you want to earn additional credit. Please return the

original report with your revised report. The revised reports are

due on or before Thu. Oct. 11.

A second Optional

Assignment on Upper Level Charts is now available. If you

make an honest effort to answer all the questions and have the

assignment done before coming to class you can earn extra credit.

If you answer at least 85% of the questions correctly you'll earn extra

credit and a "Green Card." The

assignment is due next Thursday, Oct. 4.

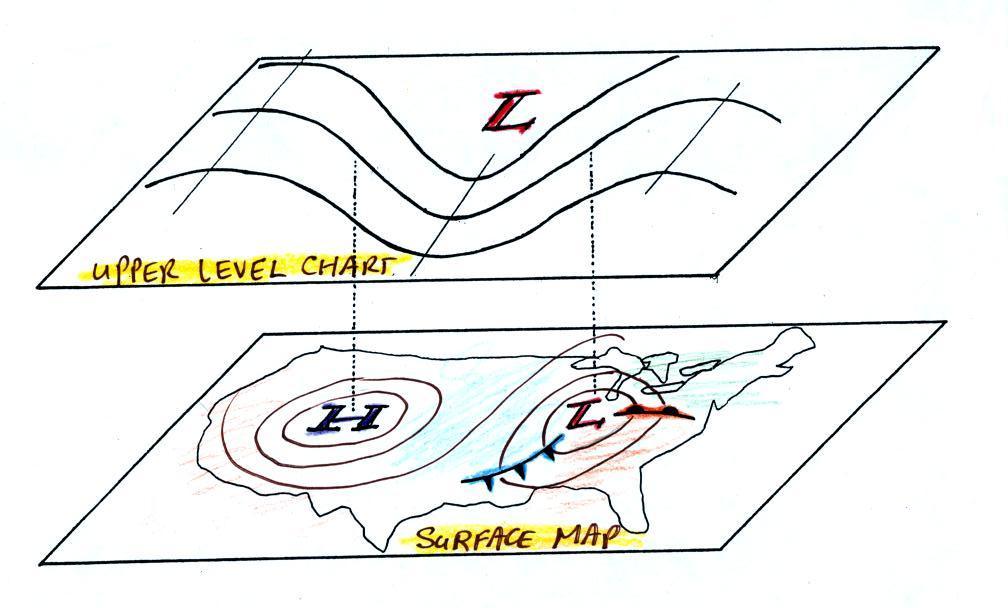

Up to this point we've been learning about surface weather

maps. Maps

showing conditions at various altitudes above the ground are also

drawn.

Upper level conditions can affect the development and movement of

surface

features (and vice versa). We covered some of the basic concepts

at the start of the period today. Some additional

supplementary information is available online.

This

supplementary

reading

provides

all

the

background

information

you'll need to be able to

answers the questions on the new optional assignment mentioned above.l

Here we'll mostly

just learn 3 basic facts about upper level

charts.

First the overall appearance is somewhat different from a surface

weather

map. The pattern on a surface map can be complex and you

generally find circular (more or less)

centers

of high and low pressure (see the bottom portion of the figure

below). You can also find closed high and low

pressure

centers at upper levels, but mostly you find a relatively simple wavy

pattern like is shown on the upper portion of the figure below (sort of

a 3-dimensional view). You'll find this basic picture on p. 41 in

the ClassNotes.

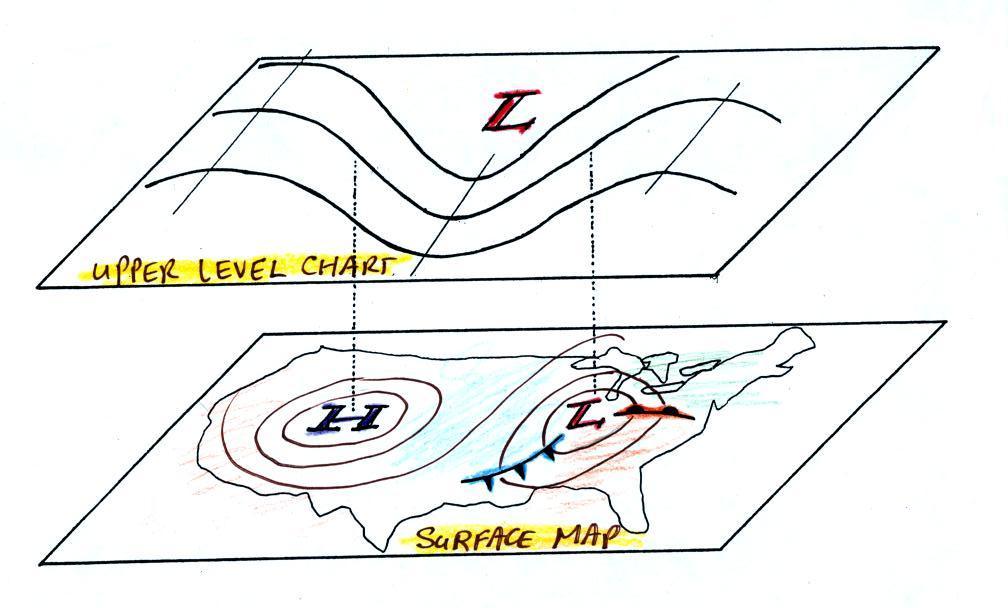

A simple upper level

chart pattern is sketched below (a map view). There are two basic

features:

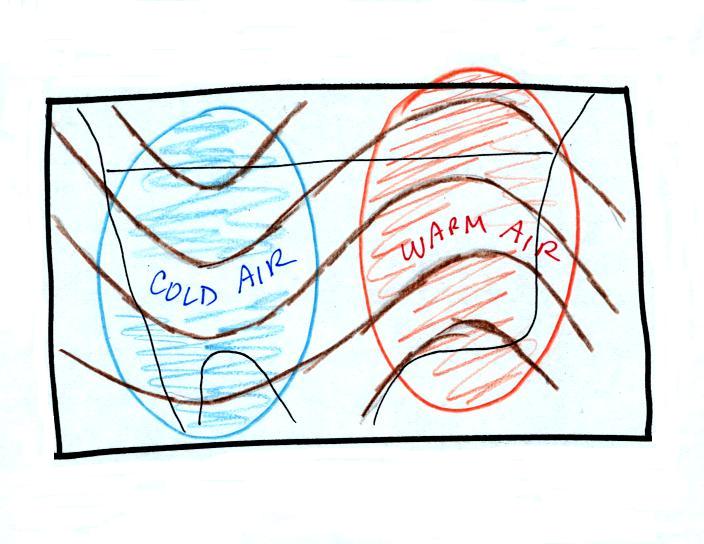

wavy lines that dip southward and have a "u-shape" and lines that bend

northward and have an "n-shape".

The u-shaped

portion of the pattern is called a trough. The n-shaped portion

is called

a ridge.

Troughs

are

produced

by

large

volumes

of

cool

or

cold

air

(the

cold

air

is

found

between

the

ground

and

the

upper

level

that

the

map

depicts).

The

western

half

of the country in the map above would

probably

be experiencing colder than average temperatures. Large volumes

of warm

or hot air produce ridges. You can find out why this is true by

reading "Upper

level

charts

pt.

2".

The

winds on upper level charts blow parallel to the contour lines

generally from west to east. This is a little different from

surface winds which blow across the isobars toward low pressure.

An example of surface winds is shown below.

That's it for this first

section. Really all you need to be able to do is

1. identify troughs and ridges,

2. remember that troughs are associated with cold air & ridges with

warm air, and

3. remember that upper level winds blow parallel to the contour lines

from west to east.

Here's the earlier picture again overlaying surface and

upper-level maps.

On

the surface map above you see centers of HIGH and LOW pressure.

The

surface low

pressure center, together with the cold and warm fronts, is a middle

latitude

storm.

Note how the counterclockwise winds spinning around the LOW move warm

air

northward (behind the warm front on the eastern side of the LOW) and

cold air

southward (behind the cold front on the western side of the LOW).

Clockwise winds spinning around the HIGH also move warm and cold

air. The

surface winds are shown with thin brown arrows on the surface map.

Note the ridge and trough features on the upper level chart. We

learned

that warm air is found below an upper level ridge. Now you can

begin to

see where this warm air comes from. Warm air is found west of the

HIGH

and to the east of the LOW. This is where the two ridges on

the

upper level chart are also found. You expect to find cold air

below an

upper level trough. This cold air is being moved into the middle

of the

US by the northerly winds that are found between the HIGH and the

LOW.

Note the yellow X marked on the upper level chart directly above the

surface

LOW. This is a good location for a surface LOW to form, develop,

and

strengthen (strengthening means the pressure in the surface low will

get even

lower than it is now. This is also called "deepening"). The

reason for this is that the yellow X

is a

location where there is often upper level divergence. Similary

the pink X

is where you often find upper level convergence. This could cause

the

pressure in the center of the surface high pressure to get even

higher. You can read more about this in Upper

level

charts

pt.

3.

The upper level winds could also cause the surface storm to weaken

(the low pressure would get higher).

.

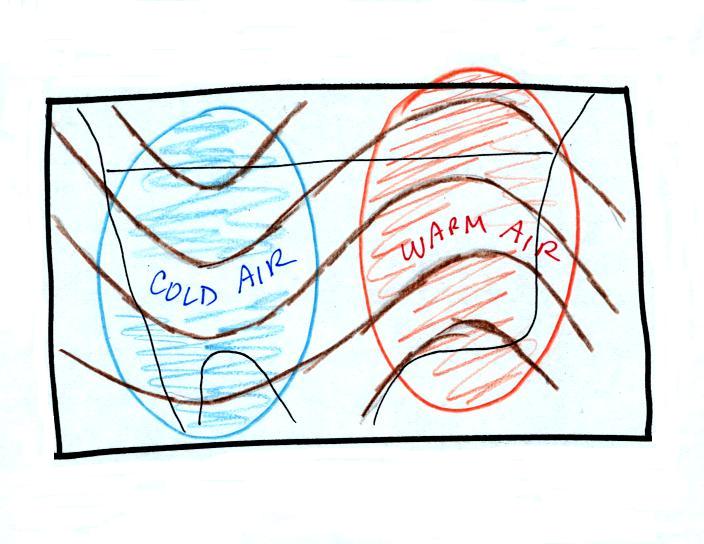

The following

picture wasn't shown in class on Thursday.

One of the things we have learned about surface LOW

pressure is that

the

converging surface winds create rising air motions. The figure

above

gives you an idea of what can happen to this rising air (it has to go

somewhere). Note the two

arrows of

air coming into the point "DIV" and three arrows of air leaving (more

air going out than coming in), this is upper level divergence).

The

rising

air can, in effect, supply the extra arrow's worth of air.

Three arrows of air come into the point marked "CONV" on the upper

level chart and two leave (more air coming in than going out = upper

level convergence).

What

happens to the extra arrow? It sinks, it is the source of the

sinking air

found above surface high pressure.

OK we're done with weather maps for the time being. Though

if interesting weather appears imminent I'll try to mention it in class

(earlier in the week it looked like the remnants of Hurricane

Miriam might bring some rainy weather to Tucson this weekend, but that

no longer seems to be the case).

The plot above at left shows the forecasted path of Hurricane

Miriam on Monday. At the time it looked like the storm was headed

toward southern Arizona. Miriam was a Category 3 hurricane (on a

scale that runs from 1 to 5) and had winds of 120 MPH. The figure

at right shows the forecasted path this morning. Miriam is now a

tropical storm with sustained winds of 40 MPH.

If we were using a textbook in this class we'd be moving into

Chapter 2! During the next couple of weeks we

will be concerned

with energy,

temperature, heat, energy transport, and

energy

balance between the earth, atmosphere, and space.

It is easy to

lose sight of the main concepts because there are so many

details. Most of the following figures are found on pps 43&44

in the photocopied

ClassNotes.

Types

of

energy

We will learn the names of several

different types or forms of

energy.

Kinetic energy is energy of motion. Some examples (both large

and microscopic scale) are mentioned

and sketched above. This is a relatively easy to visualize and

understand form of energy.

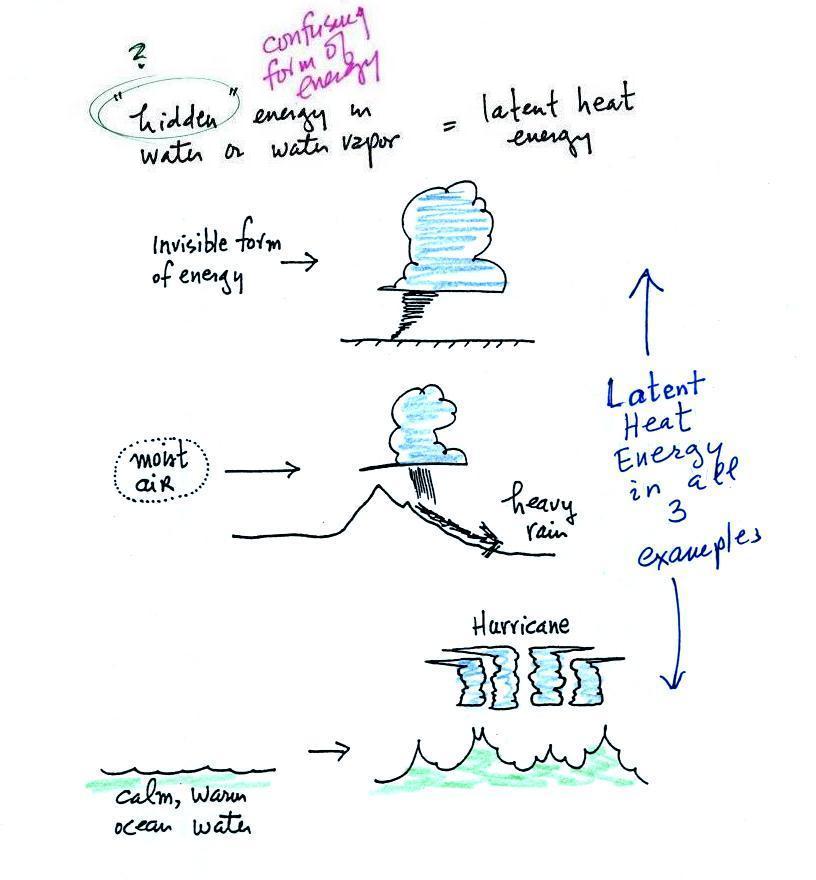

Latent heat energy is an underappreciated and

rather confusing type of energy. The word latent refers to energy that

is

hidden in water and water vapor. The hidden energy emerges when

water vapor condenses or water freezes (the energy had been added

earlier when ice was melted or water was evaporated). The fact

that the energy is hidden is part of what makes it confusing.

Radiant energy is a very important form of energy that was for

some

reason left off the original list in the ClassNotes. Sunlight is

an example of

radiant energy that we can see and feel (you feel warm when you stand

in sunlight). There are many types of radiant energy

that are invisible (such as the infrared light that people emit - something I didn't

mention in class).

Electromagnetic radiation is another name for

radiant energy.

Energy

transport

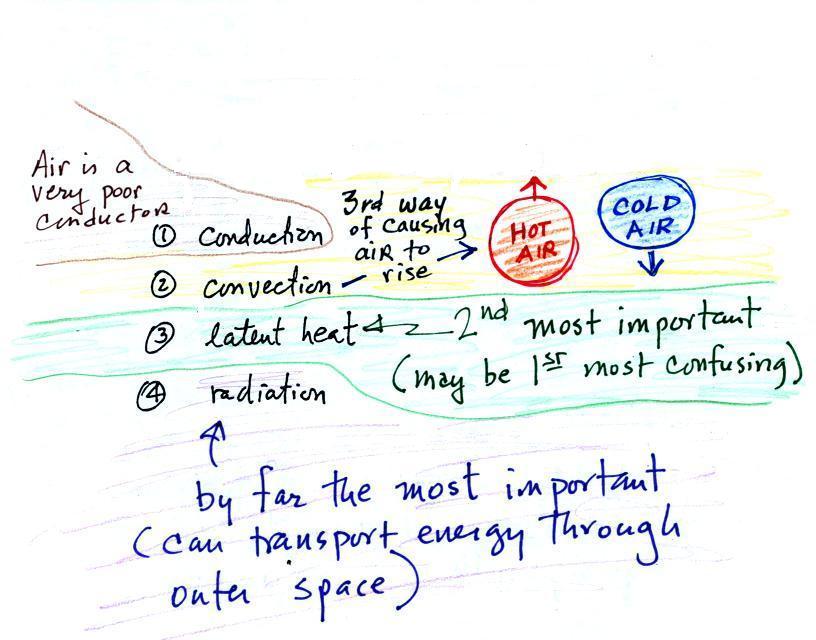

Four energy transport

processes are listed below.

By far the

most important process is at the bottom of the list above. Energy

transport in the form of

electromagnetic radiation (sunlight is a common

form of electromagnetic radiation) is the

only process that can transport energy through empty space.

Electromagnetic radiation travels both to the earth (from the sun) and

away from the earth back into space. Electromagnetic radiation is

also

responsible for about 80% of the

energy transported between the ground and atmosphere.

You might be

surprised to learn that latent heat is the second most important

transport process.

Rising parcels of warm air and sinking parcels of cold air are

examples of free convection. Because of convection you feel

colder or

a cold windy day than on a cold calm day (the wind chill effect).

Ocean currents are also an example of convection.

Ocean currents

transport energy from the warm tropics to colder polar regions.

Convection is a 3rd way of causing rising air

motions in the atmosphere (convergence

into centers of low pressure and fronts are other 2 ways we've

encountered so far)

Conduction is the least important energy transport at least in the

atmosphere. Air is such a poor conductor of energy that it is

generally considered to be an insulator.

Energy

balance

and the

atmospheric greenhouse effect

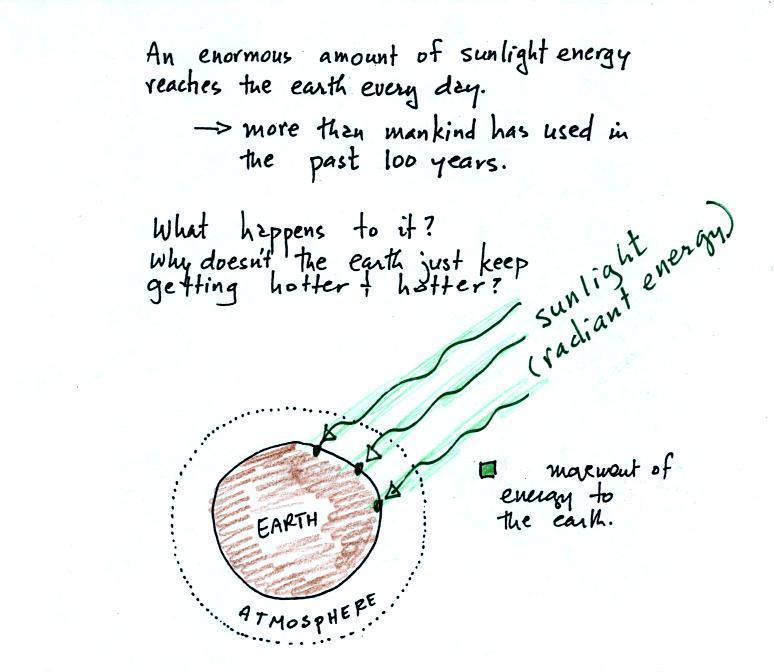

The next picture

(the figure in the ClassNotes has been split into three

parts for improved clarity) shows energy being transported from the sun

to

the earth in the form of electromagnetic radiation.

We are aware of this energy because

we can see it (sunlight

also contains invisible forms of light) and feel it. With all of

this energy arriving at and

being

absorbed by the earth, what keeps the earth from getting hotter and

hotter? If you park your car in the sun it will heat up.

But there is a limit to how hot it will get. Why is that?

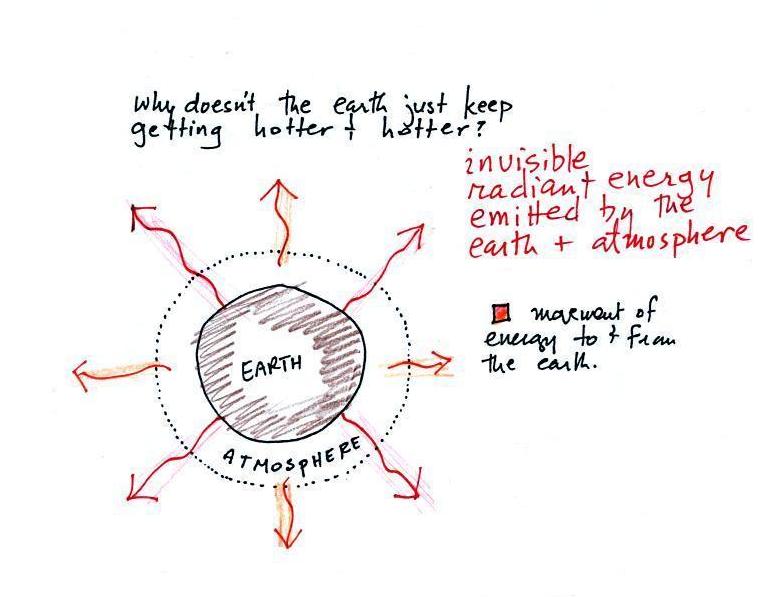

It might be helpful when talking about energy balance to think of a

bank account. If you periodically deposit money into your account

why doesn't the balance just grow without limit. The answer is

that you also take money out of the account and spend it. The

same is true of energy and the earth. The earth absorbs incoming

sunlight energy but also emits energy back into

space (the orange and pink arrows in the figure below). Energy is

being emitted by both the surface of the earth and the atmosphere.

Energy is emitted in the form of

infrared light is an

invisible form of energy (it is weak enough that we

don't usually feel it either). A balance

between incoming and outgoing energy is achieved and the earth's annual

average temperature remains constant.

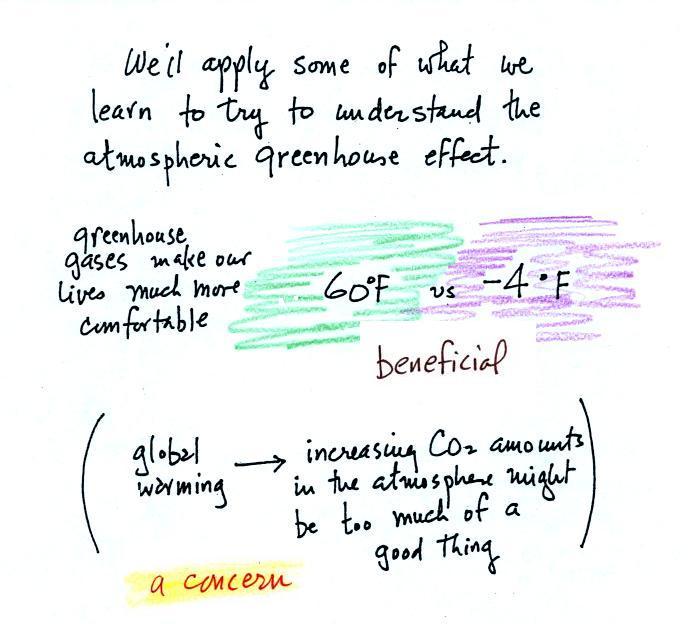

We will also look closely at energy transport between the earth's

surface and the atmosphere (see the figure below). This is where latent

heat energy transport,

convection and conduction operate (they can't transport energy beyond

the atmosphere and into outer space).

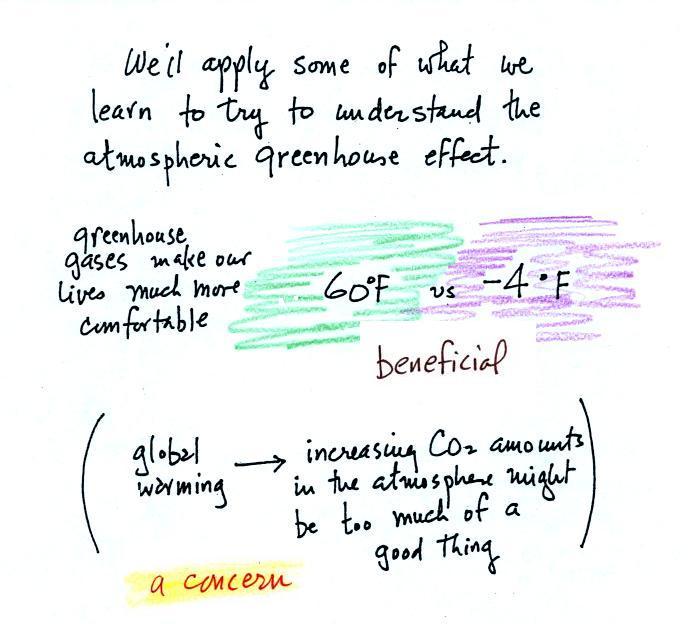

That

is

also

where

the

atmospheric

greenhouse

functions.

That

will

be

a important goal -

to

better understand how the atmospheric greenhouse effect works.

The detrimental side is that atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations

are increasing (no real debate about that). This might enhance or

strengthen the greenhouse

effect and

cause the earth to warm (some debate here particularly about how

much warmer there might be). While that doesn't necessarily

sound bad

it could have many unpleasant side effects (lots of debate and

uncertainty about this also). That's a subject

we'll explore briefly later in the semester.

We kind of rushed through the remaining material - I apologize for

that. Here's a picture of me back in my office banging my head

against a wall which is what I do in cases like that.

I was in a hurry because I wanted to have time for an

experiment at the end of class. And then after I've hit my head a

few time I try to make amends and explain the material more clearly on

the online notes.

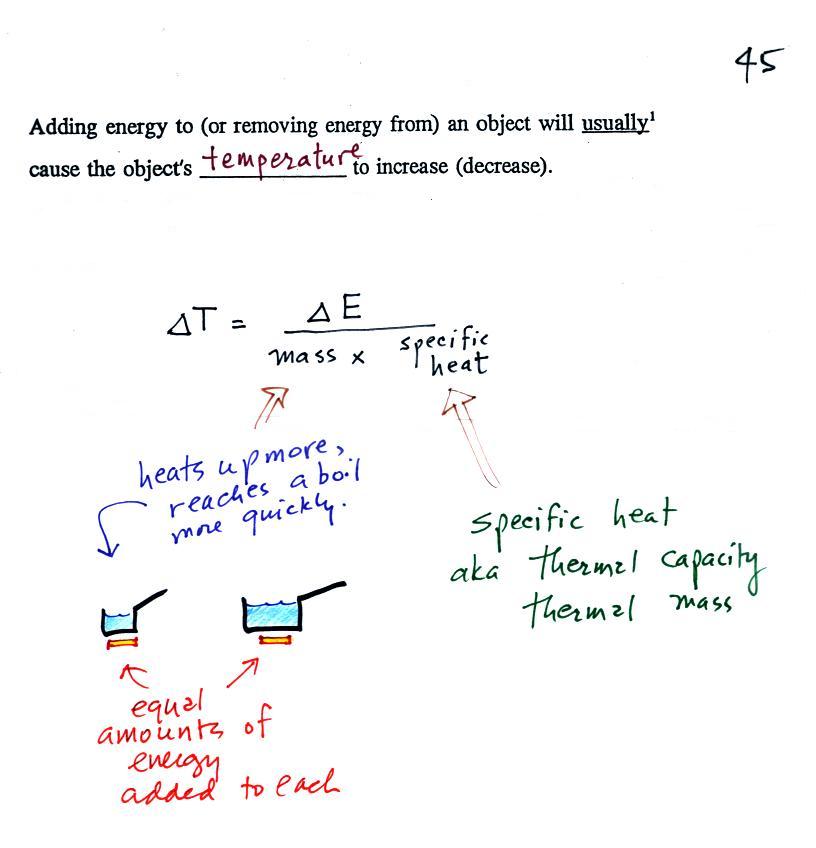

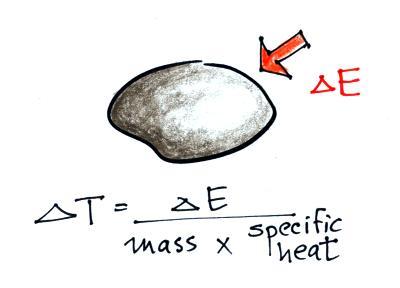

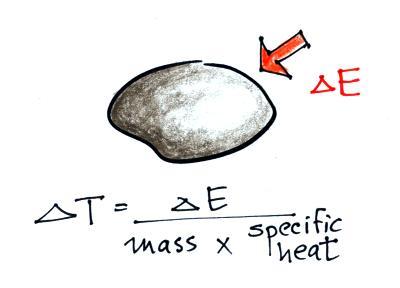

When you

add energy to an object, the object will usually

warm

up (or if you take energy from an object the object will

cool). It is relatively easy to come up with an equation that

allows

you to figure out what the temperature change will be (this is another

equation I'll write on the board before the next quiz if you

ask me to - try

to understand it, you don't have to memorize it).

The temperature change, ΔT, will

first depend on

how much energy was added, ΔE. This is a

direct proportionality, so ΔE is in the

numerator of the

equation (ΔE and ΔT are

both positive when energy is added,

negative when energy is removed)

When you add equal amounts of energy to large and small pans

of water, the small pan will heat up more

quickly. The temperature change, ΔT, will

depend on the

amount of water, the mass. A small mass will mean a large ΔT,

so

mass

should

go

in

the

denominator

of

the

equation.

Specific heat is what we use to account for the fact that

different

materials

react differently when energy is added to them. A material with a

large specific heat will warm more slowly than a material with a small

specific heat. Specific heat has the same kind of effect on ΔT

as

mass. Specific heat is sometimes called "thermal mass" or

"thermal capacity." You can think of specific heat as

being thermal inertia - a substance with high specific heat, lots of

thermal inertia, will be reluctant to change temperature.

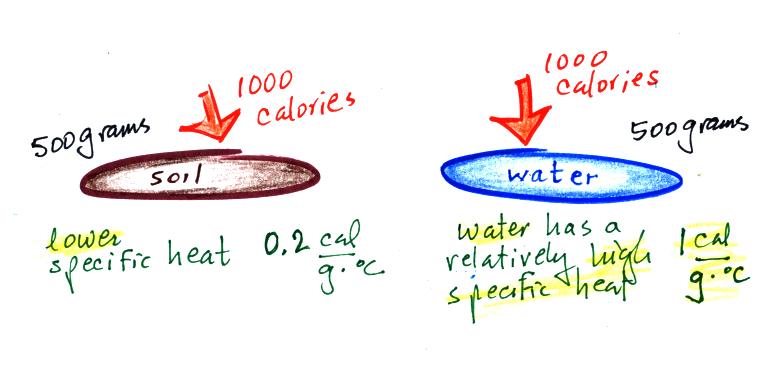

Here's an important example that will show the effect of specific

heat (middle of p. 45).

Equal

amounts of energy (1000 calories, note that calories are units of

energy) are added to

equal masses (500 grams) of water and soil. We use water and soil

in the

example because most of the earth's surface is either ocean or land.

Before we do the calculation, try to guess which material will warm up

the most. Everything is the same except for the specific

heats. Will water with its 5 times larger specific heat warm up

more or less than the soil?

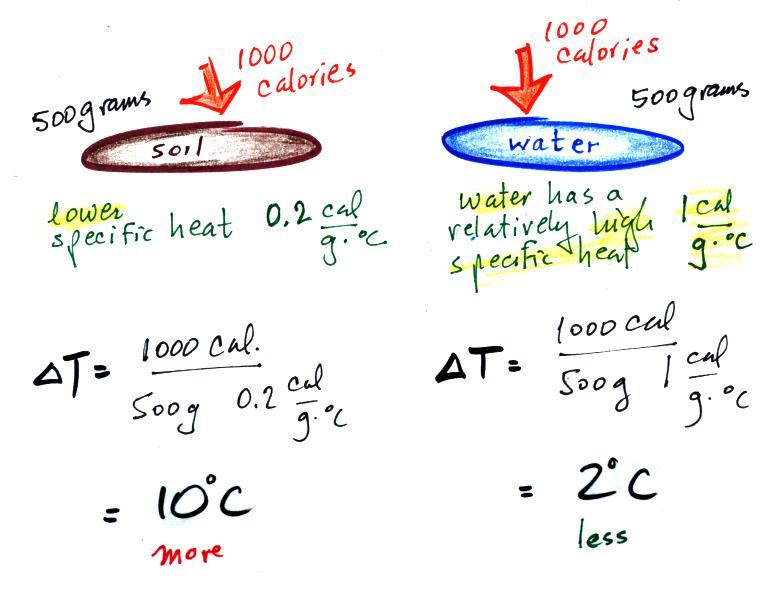

Here are the details of the calculation.

With its higher specific heat, the water doesn't heat up nearly as

much as the soil. If we had been removing energy the wouldn't

cool off as much as the soil would.

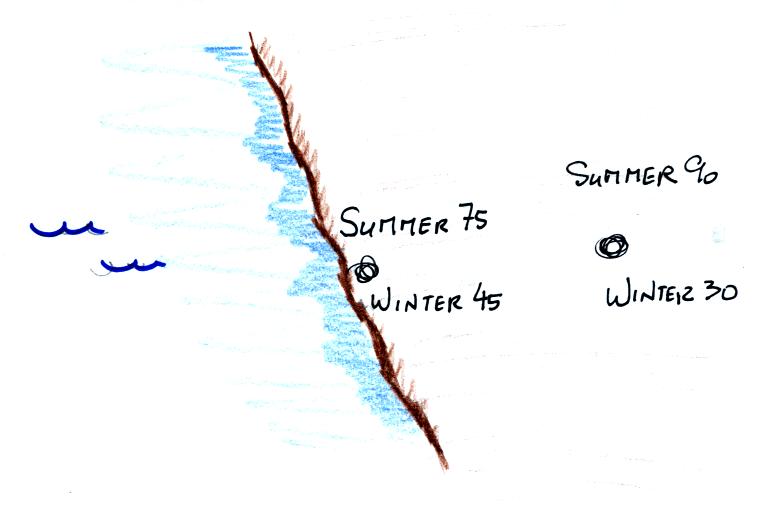

These different rates of warming of water and soil have

important effects on regional climate.

Oceans moderate the climate.

Cities near a large body

of water won't warm as much in the summer and won't cool as much during

the winter compared to a city that is surrounded by land. Water's

ΔT is smaller than land's because water has higher specific

heat.

The yearly high and low monthly average temperatures are shown at

two locations above. The city on the

coast has a 30o F annual range of temperature (range is the

difference between the summer and winter temperatures). The

city further

inland (assumed to be at the same latitude and altitude) has an annual

range of 60o F. Note that both cities have the same 60o

F annual

average temperature. We'll see a much more dramatic example of

the moderating effect of water on climate in a couple of weeks.

Here's another situation where you

can take advantage of water's

high specific heat to moderate "micro climate." We didn't have time

to discuss this in class.

I usually plant tomatoes in my

vegetable garden in February so that they can start to make tomatoes

before it starts to get too hot in May. In February it

can still get cold enough to kill tomatoes (the brocolli

and lettuce in the background can handle a

light frost) so you have to protect them.

Here's one way of doing that.

You

can

surround

each

plant

with

a

"wall

o

water"

-

a

teepee

like

arrangement

that

surrounds

each plant. The cylinders are

filled with water and they take advantage of

the high specific

heat of water and won't cool as much as the air or soil would during a

cold

night. The walls of water produce a warm moist microclimate that

the tomato seedlings love. The plastic is transparent so plenty

of sunlight can get through.

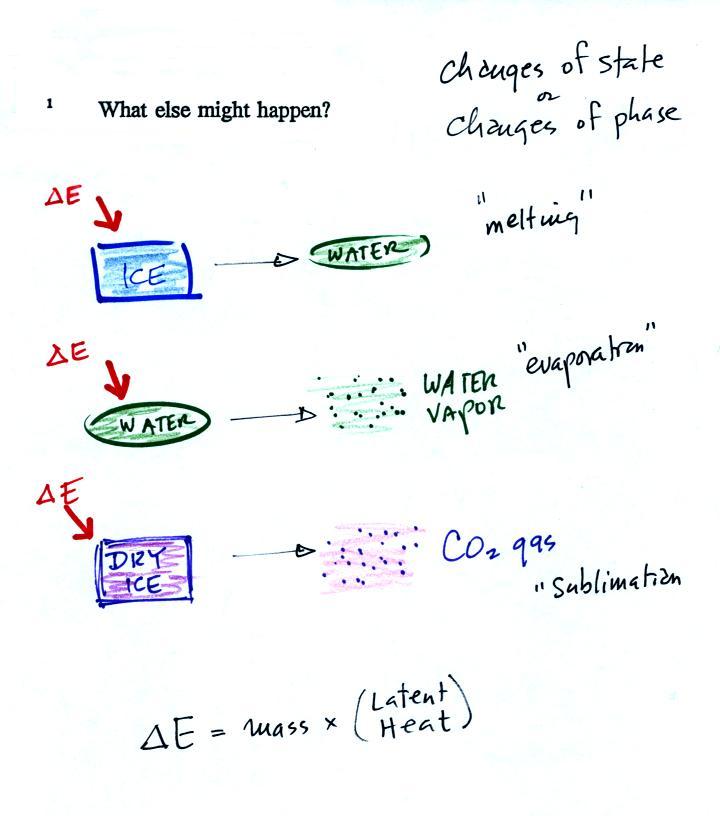

Adding

energy to an object will usually cause it to warm. But there

is another possibility (bottom p. 45), the object could change

phase (change

from solid to liquid or

gas). Adding energy to ice might cause

the

ice to melt. Adding energy to water could cause it to

evaporate. We hurried through

this a little bit in class.

The equation at the bottom of the

figure above allows you to

calculate how much energy is required to melt ice or evaporate water or

sublimate dry ice. You multiply the mass by the latent heat, a

variable that depends on the particular material that is changing

phase. The latent heat of vaporization (evaporation) is the

energy required to evaporate 1 gram of a material.

If you add energy to or remove

energy from an object, the

object

will usually change temperature. You can calculate the

temperature change if you know the object's mass and its specific

heat. That's the equation we used in the example calculation

above. It's shown again below.

We conducted an experiment in the

last part of the class and we needed to be able to measure ΔE.

We'll stick a thermometer into the object and measure any

changes in

temperature that occur.

And on to the in-class experiment. A couple of

groups of students from

the class were nice enough to volunteer

to

perform the experiment. They'll be able to

write a report about the experiment

and use the data you collected to satisfy the Experiment Report part of

the Writing Requirements. I.e. they won't have to worry about

checking out materials and doing Expt. #1, #2, or #3. A couple of

the students had done Expt. #1. I got to thinking after class

that they deserved something for their effort and I think I'll give

them each a Green Card.

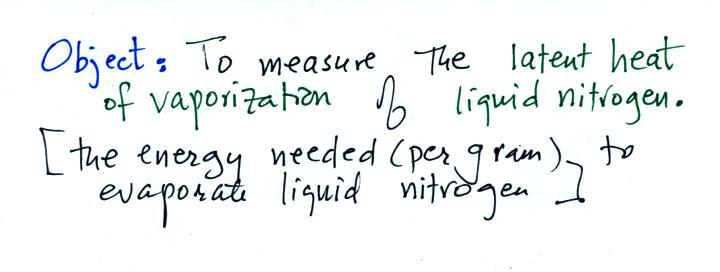

Here's the object of the experiment:

The students that are doing Experiment #2 are doing something

similar, they are measuring the latent heat

of fusion of ice, the energy needed to melt one gram of ice.

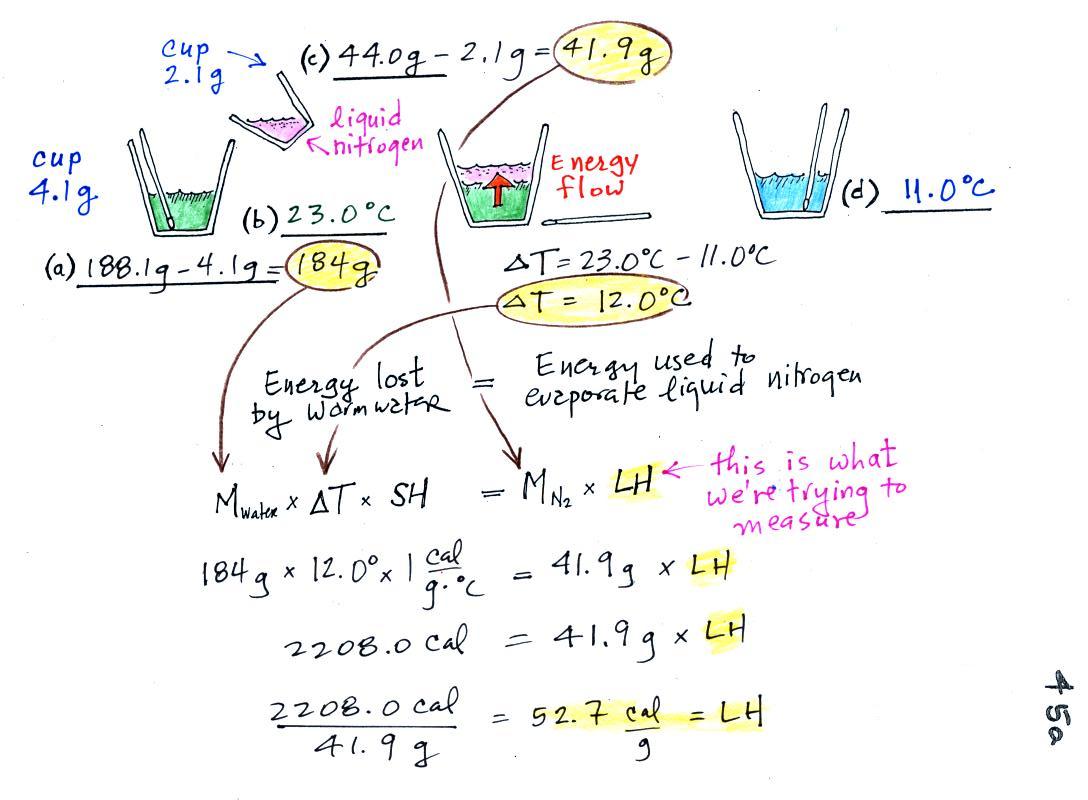

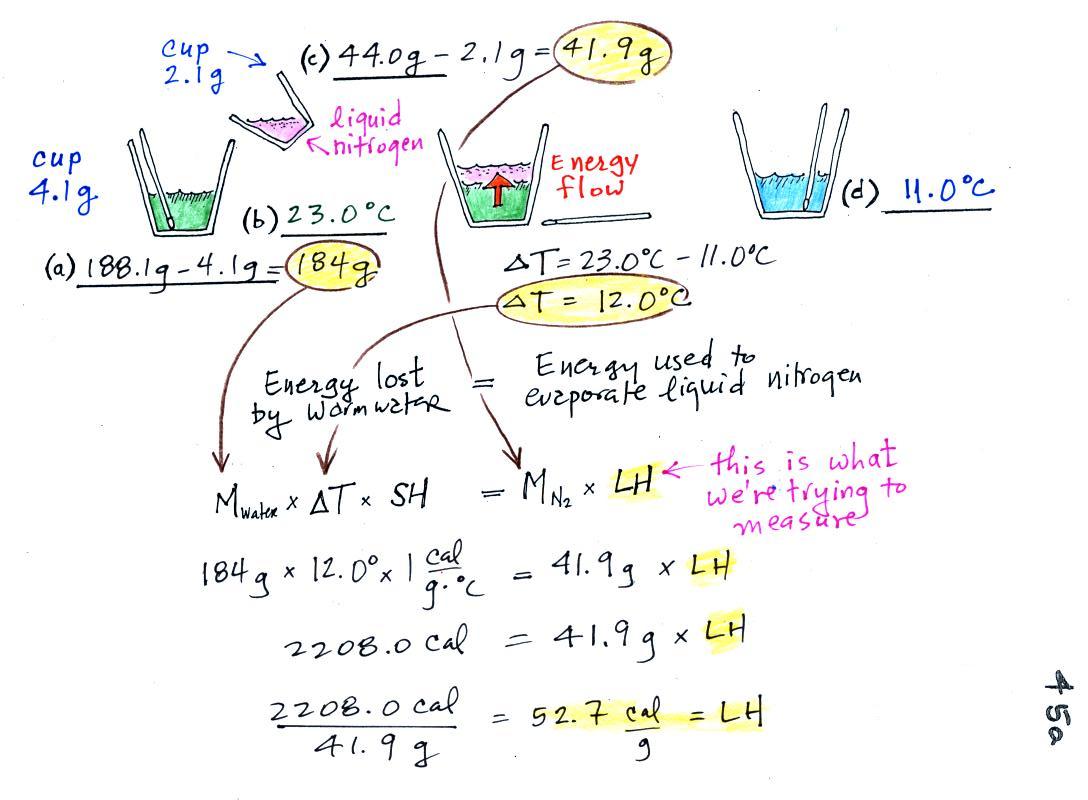

Here's the data that one of the groups collected in class.

This will be hard to figure out even after having cleaned things up a

bit after class.

So here's a step by step

explanation of what the students did:

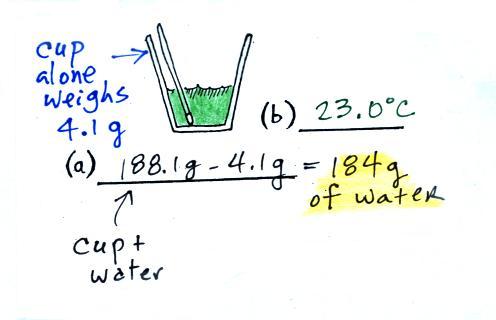

(a)

Some room temperature water poured into a styrofoam cup weighed

188.1 g. The cup itself weighed 4.1 g, so they had 184.0 g of

water. The water's temperature was measured with the

thermometer and was

23.0 C (room temperature).

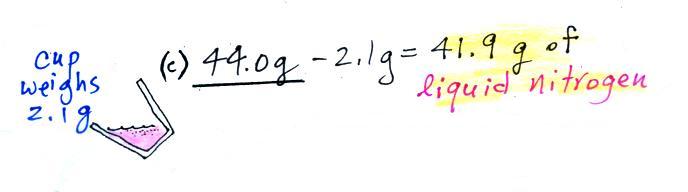

(b)

Some liquid nitrogen was poured into a second smaller styrofoam

cup. That weighed 44.0 g. Subtracting the 2.1 g weight of

the cup means we had 49.1 g of liquid nitrogen.

We don't need to measure the temperature of the liquid nitrogen

(doing so would probably destroy the thermometer). It had already

warmed up as much as it ccould ( to -320 F or something like

that). Any

additional energy added to the liquid nitrogen will cause it to

evaporate.

(c)

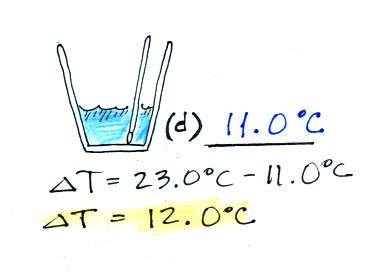

After the liquid nitrogen had evaporated the water's

temperature was remeasured. It had dropped to 11.0 C.

We started out with water that was 23.0 C, so that is a temperature

drop of 12.0 C.

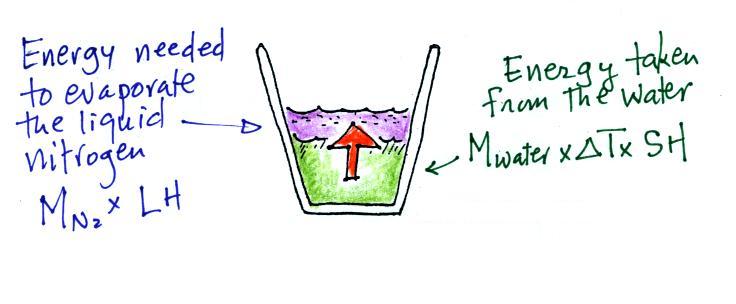

It takes energy to turn liquid nitrogen into nitrogen gas.

The energy needed will be taken from the water (the red arrow below,

energy naturally flows from hot to cold).

Because the experiment was performed in an insulated sytrofoam cup we

will assume all of the energy taken from the water is used to evaporate

nitrogen. Minimal energy flows into the room air or anything like

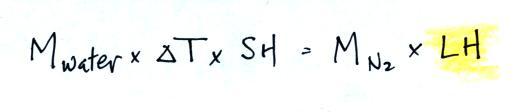

that. We will set the two equations above equal to each

other. This is an energy balance equation.

We know the mass of the nitrogen that we started with and that was

eventually evaporated (41.9 g) and the mass of the water (184.0

g). We measured the ΔT (12.0 C) and we

know the specific heat of water (1 cal/g C). We substitute them

into the equation above and solve for LH, the latent heat of

vaporization of liquid nitrogen. Here are the details of the

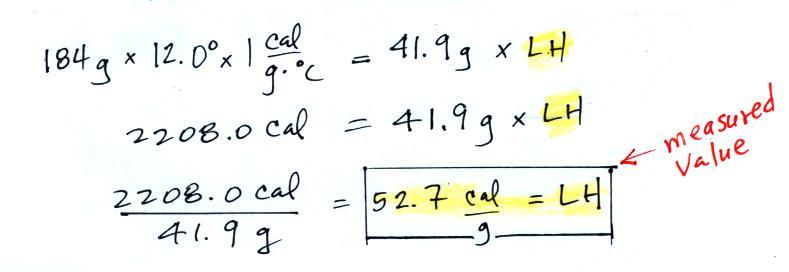

calculation:

A

responsible & trustworthy student in

the class (though not a Buddhist monk it turns out) informed us that

the known value is 48 cal/g, so this measured value is pretty close to

the known value.