| Year |

Deaths |

Total

Damage

($billions) |

| 2001 |

24 |

5.1

|

| 2002 |

51 |

1.4 |

| 2003 |

14 |

1.9 |

| 2004 |

34 |

19.6 |

| 2005 |

1016 |

95.1 |

| 2006 |

0 |

<

1 |

| 2007 |

1 |

<

1 |

| 2008 |

12 |

8.0 |

| 2009 |

2 |

<

1 |

| 2010 |

0 |

<

1 |

| 2011 |

9 |

< 1 |

| 2012 |

4 |

< 1 |

| 2013 |

1 |

< 1 |

|

|

|

|

| Similarities |

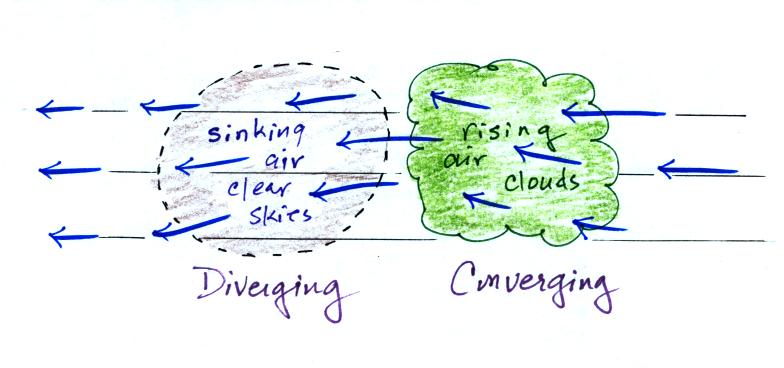

| 1. both types of storms have low pressure centers (the term cyclone refers to winds blowing around low pressure) |

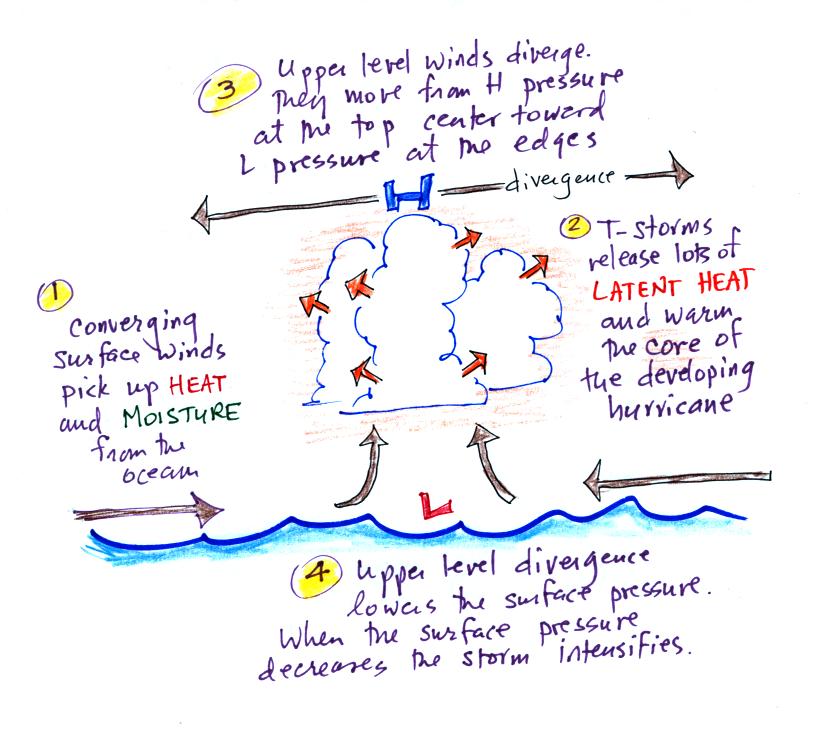

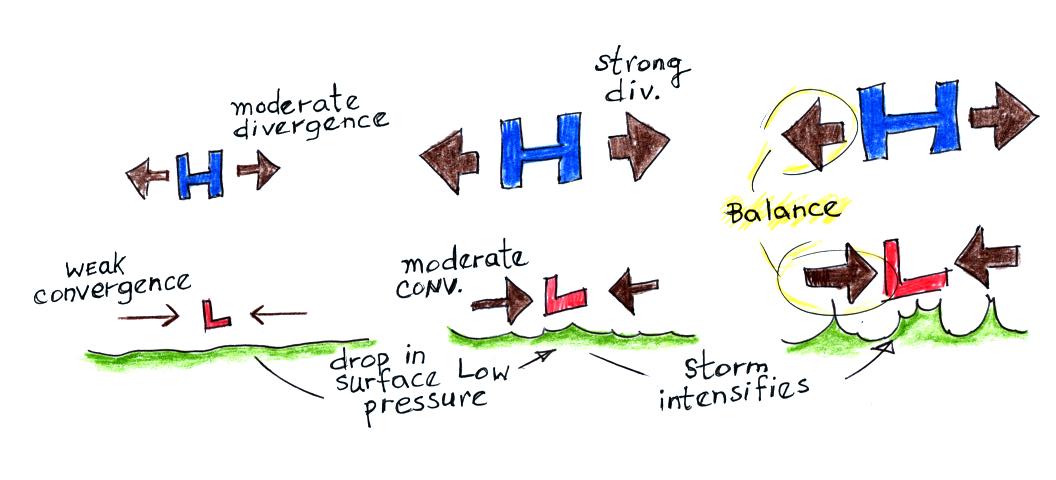

| 2. upper level

divergence is what causes both types of storms to

intensify (intensification means the surface low

pressure gets even lower) |

| Differences

(the order may differ from that given in class) |

|

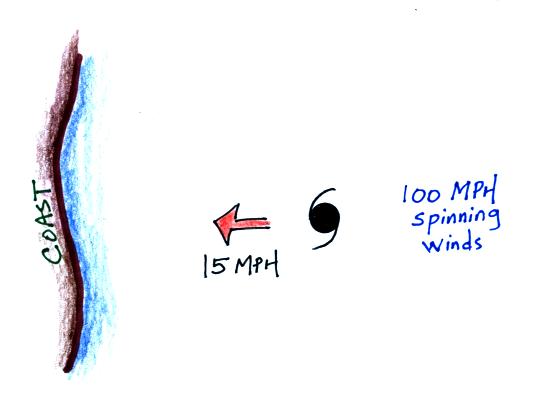

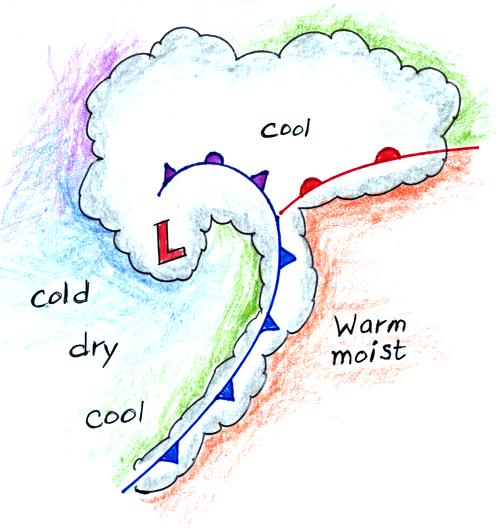

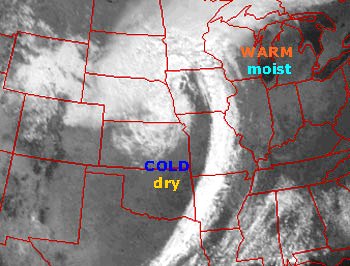

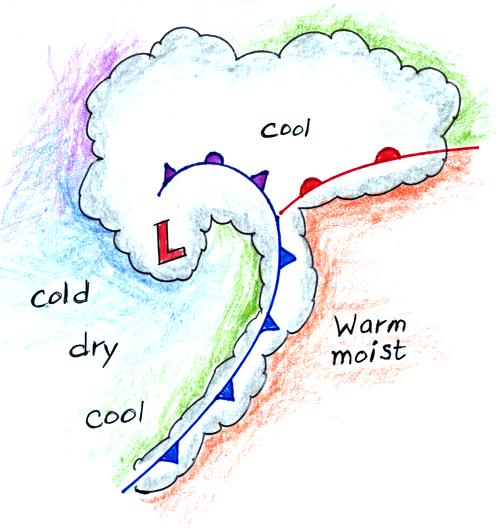

| 1. Middle latitude

storms are bigger, 1000 or 2000 km in diameter (half the US) |

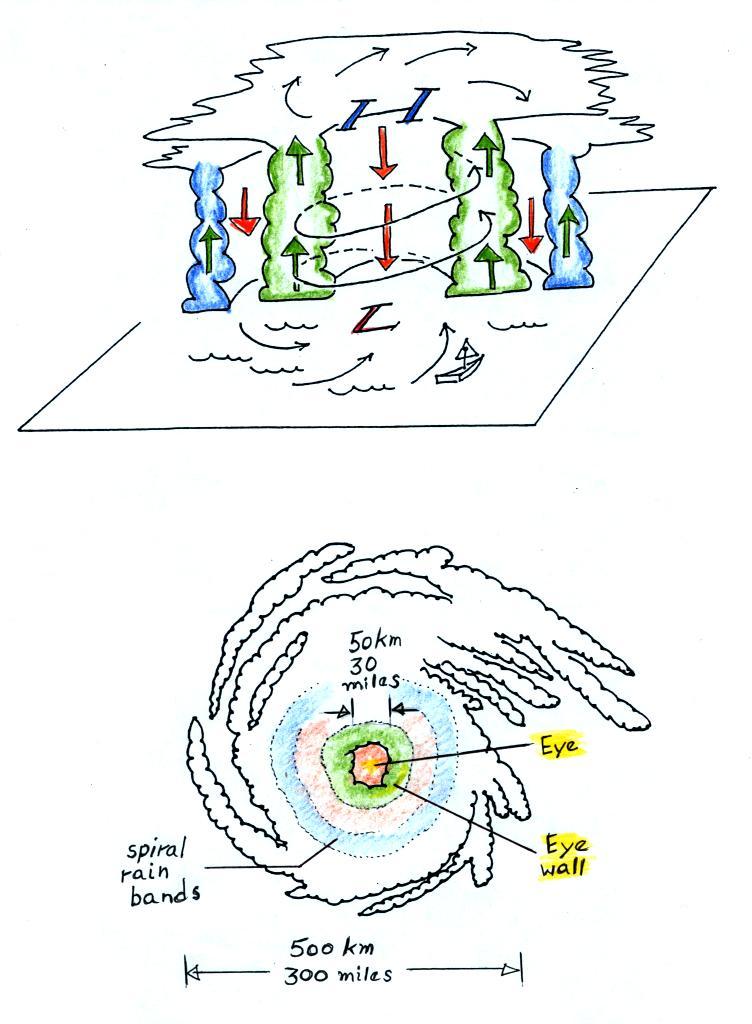

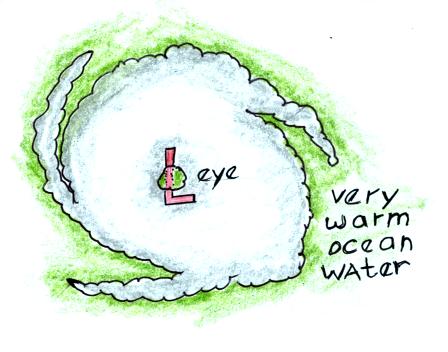

1. Hurricanes are

smaller, a few 100s of km in diameter (fill the Gulf of Mexico) |

| 2. Formation can occur

over land or water |

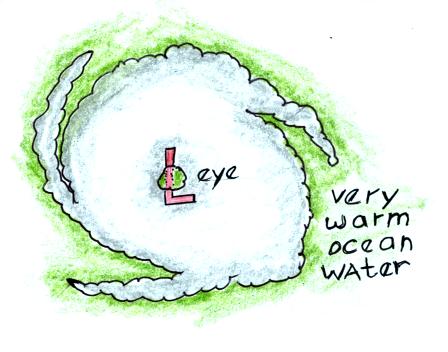

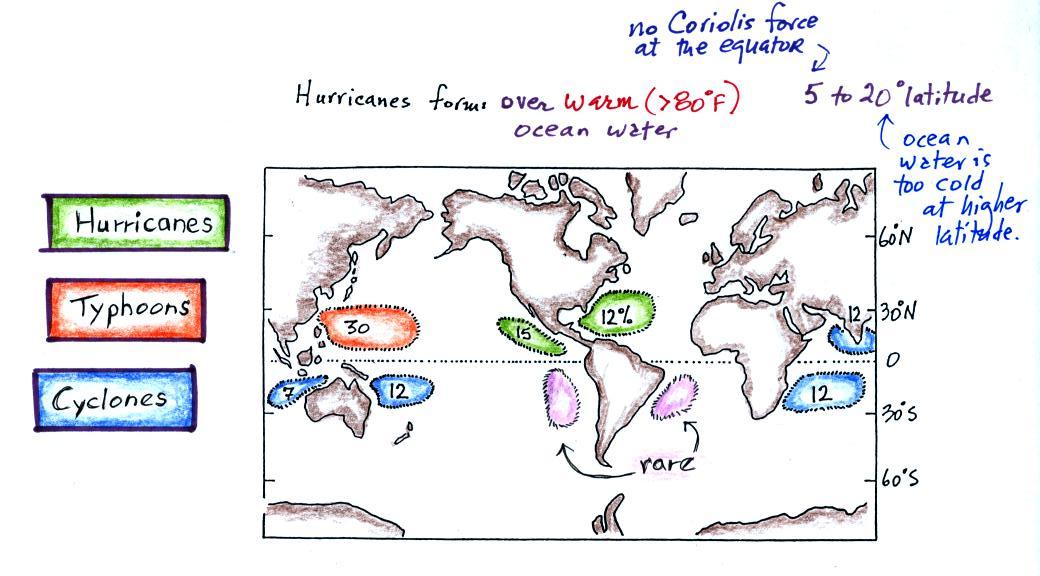

2. Can only form over

warm ocean water & weaken rapidly when they move over land or cold water |

| 3. Form at middle (30o

to 60o) latitudes |

3. Form in the sub

tropics, 5o to 20o latitude |

| 4. Winds at middle

latitudes (the prevailing westerlies) move these storms

from west to east |

4. Easterly winds in the

tropics (the trade winds) move hurricanes from east to west |

| 5. Storm season: late

fall and winter (strong thunderstorms and

tornadoes in early spring) |

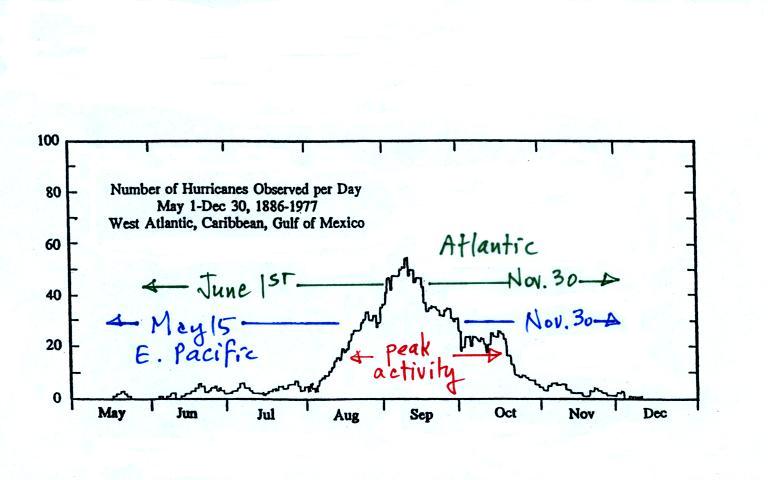

5. Storm season: late

summer to fall (when ocean water is warmest) |

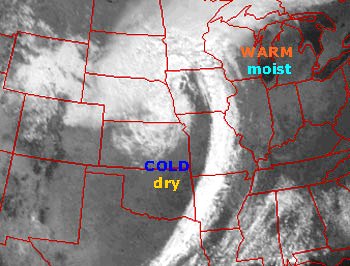

| 6. Warm and cold air

masses collide along fronts |

6. just warm moist air |

| 7. All types of

precipitation: rain, snow, sleet, freezing rain |

7. Mostly just lots of rain (often a foot or more) |

| 8. Only an occasional

storm gets a name ("The Perfect Storm", "Storm of the Century", "Superstorm Sandy" etc.) |

8. Tropical storms &

hurricanes all get names (determined by an

international committee of some kind) |

| Normal Pacific hurricane

activity |

Normal Atlantic hurricane activity |

| 16

tropical storms per year 8 reach hurricane strength 0 hit the US coastline |

10

tropical storms per year 6 reach hurricane strength 2 hit the US coastline |

| this

year 20 tropical storms (4th most active) 14 hurricanes (9 major) Hurricane Iselle struck the big island of Hawaii |

this

year

8 tropical storms 6 hurricanes (2 major) 1 made landfall in the US |