Upper Level Charts Pt. 2

There is an Optional

Assignment that accompanies this 3-part reading material on

Upper Level Charts.

Here's a little more in depth look at upper-level charts.

You'll find most of the figures below on pps. 115-119 in the

photocopied ClassNotes.

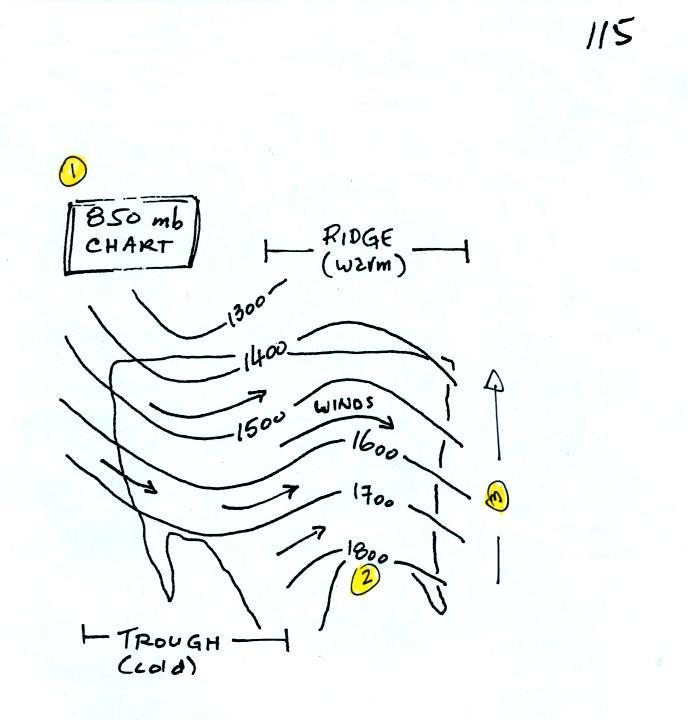

Hopefully you still remember the trought (u-shape)

and ridge (n-shape) features introduced in

Pt. 1, the fact that cold air is found under an upper level trough

and warm air below a ridge, and that the upper level winds blow

parallel to the contour lines and from west to east.

1. After you've finished reading this

section you should better understand what the title "850 mb Chart"

on the upper level map above refers to.

2. You should also understand what the

numbers on the contour lines represent and what their units

are. On a surface map contours of pressure, isobars, are

normally drawn. That is usually not the case on upper level

charts. You'll have a better idea of where the names trough

and ridge come from.

3. Note that the values on the contours

decrease as you move from the equator toward higher

latitude. You should understand why that happens

(temperature also decreases as you move toward higher latitude,

maybe that is the explanation). You should understand why

troughs and ridges are associated with cold and warm air,

respectively.

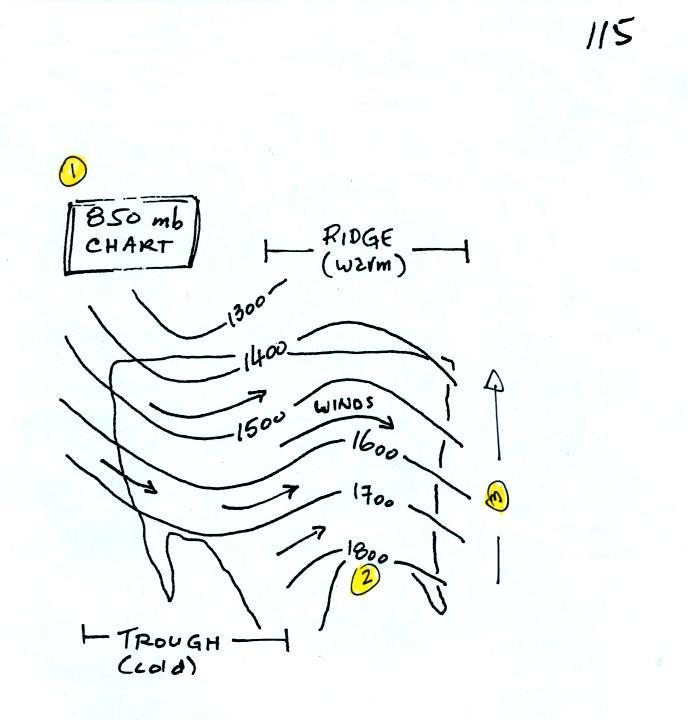

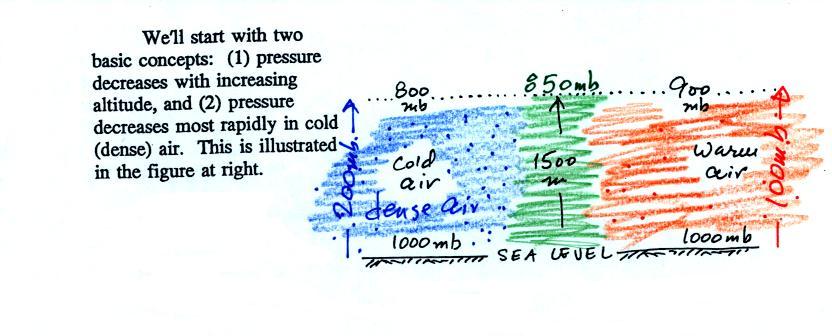

You really only need to remember two things from earlier in the

semester (you'll find the figure above at the bottom of p. 115 in

the photocopied Classnotes): (1) pressure decreases with

increasing altitude, and (2) pressure decreases more rapidly

in cold high-density air than it does in warm low density

air.

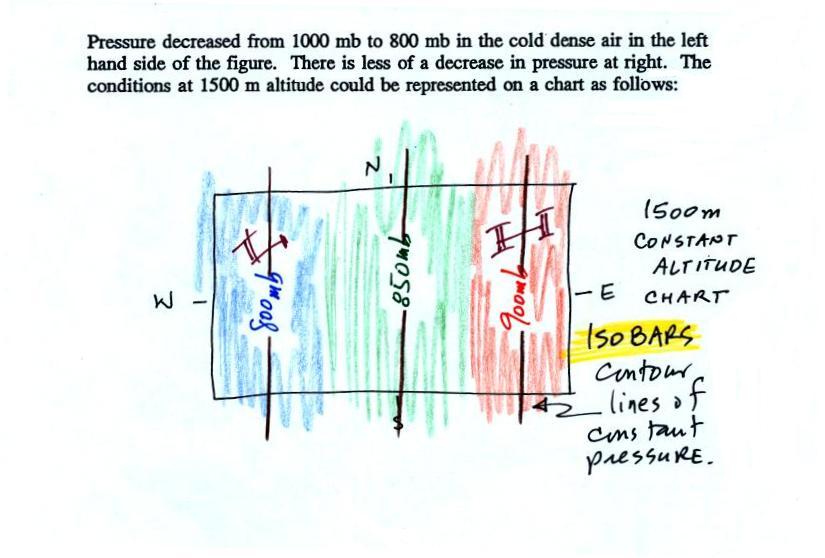

Pressure drops from 1000 mb to 800 mb, a 200 mb change, when

moving upward 1500 meters in the cold air. It decreases from

1000 mb to 900 mb, only 100 mb, in the same distance in the

warm low density air.

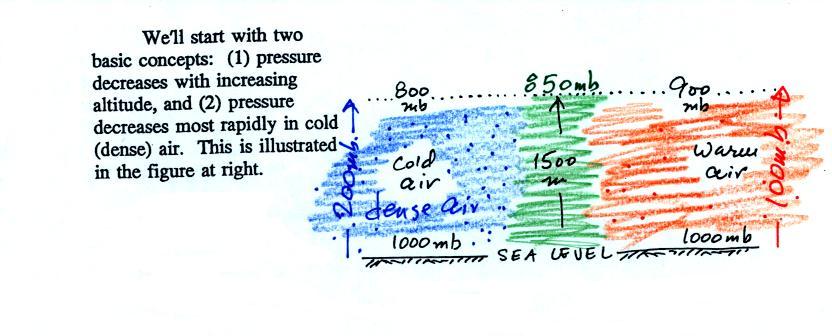

Isobars on constant altitude upper level charts

One way of depicting upper level conditions would be to

measure pressure values at some fixed altitude above the

ground. This approach is shown above. Pressures range

from 800 mb to 900 mb at 1500 meters altitude. The pressure

pattern could then be plotted on a constant altitude chart using

isobars (figure below). Note the lowest pressures are found

in the cold air, higher pressures would be found in the warm air.

That would seem to be a logical way of mapping upper level

atmospheric conditions. Unfortunately that isn't how things

are done.

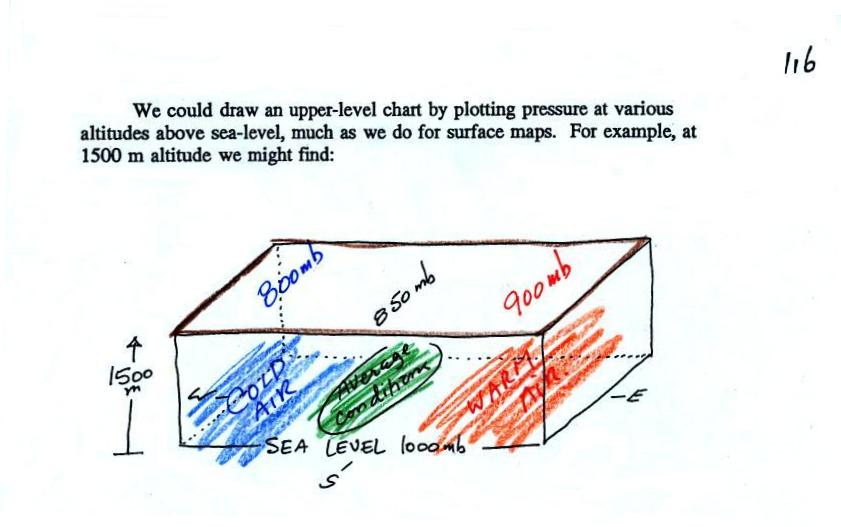

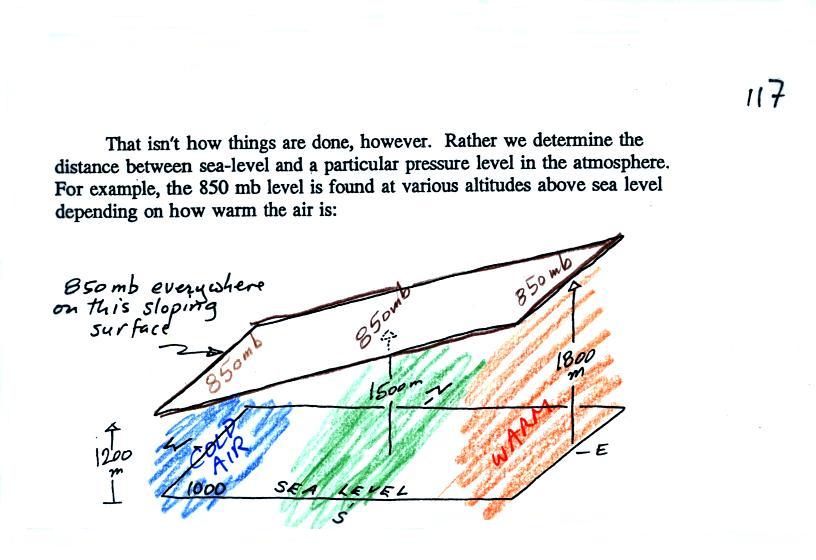

Height contours on constant pressure (isobaric) upper

level charts

Just to make life difficult for NATS 101 students,

meterologists do things differently. Rather than

plotting conditions at a constant altitude above the ground,

meterologists measure and plot conditions at a particular

reference pressure level above the ground.

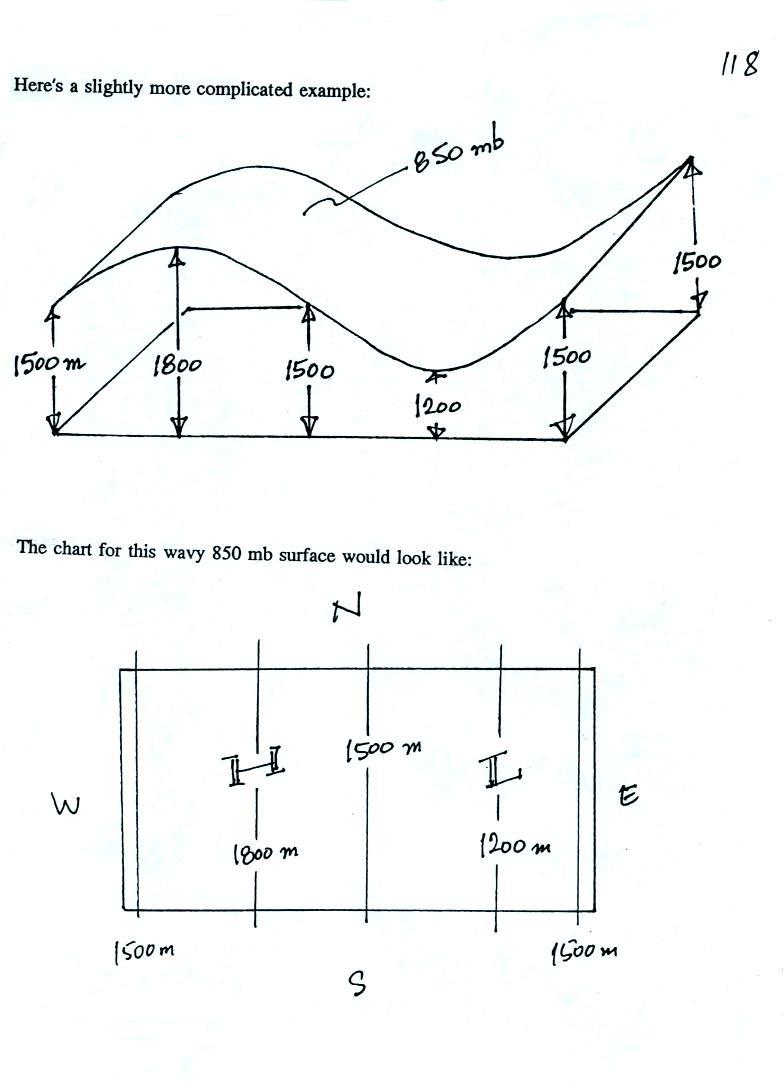

In the picture above you start at the ground (where the pressure

is 1000 mb) and travel upward until you reach 850 mb

pressure. You make a note of the altitude at which that

occurs. In the cold dense air at the left pressure decreases

rapidly so you wouldn't need to go very high, only 1200

meters. In the warm air at right pressure decreases more

slowly, you would have to going higher, to 1800 m.

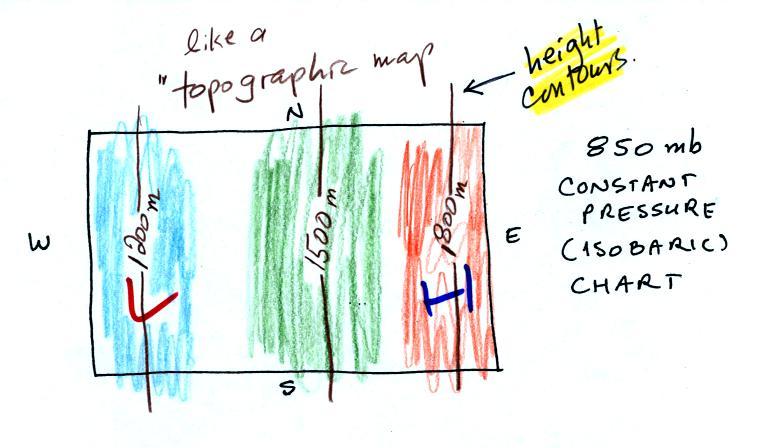

Every point on the sloping surface above has the same pressure,

850 mb. The altitude above the ground is what is

changing. You could draw a topographic map of the sloping

constant pressure surface by drawing contour lines of altitude or

height.

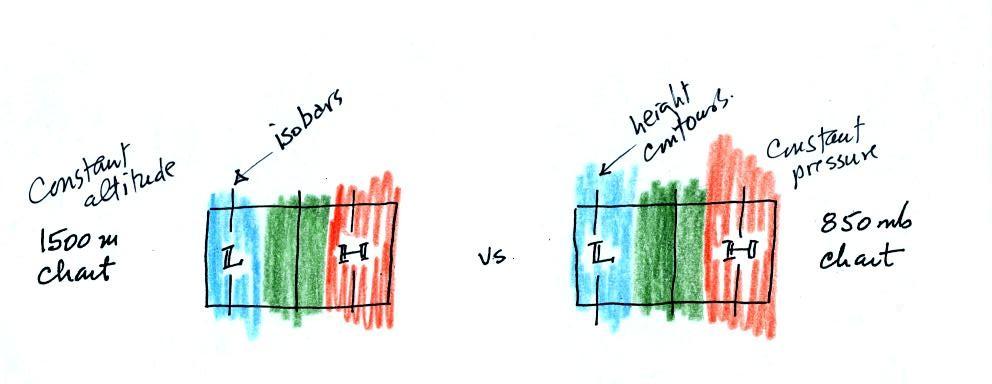

The two kinds of charts (constant altitude or constant pressure)

are redrawn below.

The numbers on the contour lines have been left off in order to

clearly see that both types of maps have the same overall pattern

(they should because they're both depicting the same upper level

atmospheric conditions).

In the example above temperature changed smoothly from cold to

warm as you move from left to right (west to east).

See if you can figure out what temperature pattern is producing

the wavy 850 mb constant pressure surface below.

It shouldn't be too hard if you remember that the 850 mb level

will be found at relatively high altitude in the warm air where

pressure decreases slowly with increasing altitude. The 850

mb level will be found closer to the ground in cold air where

pressure decreases rapidly with increasing altitude. Click here when you think you have it

figured out.

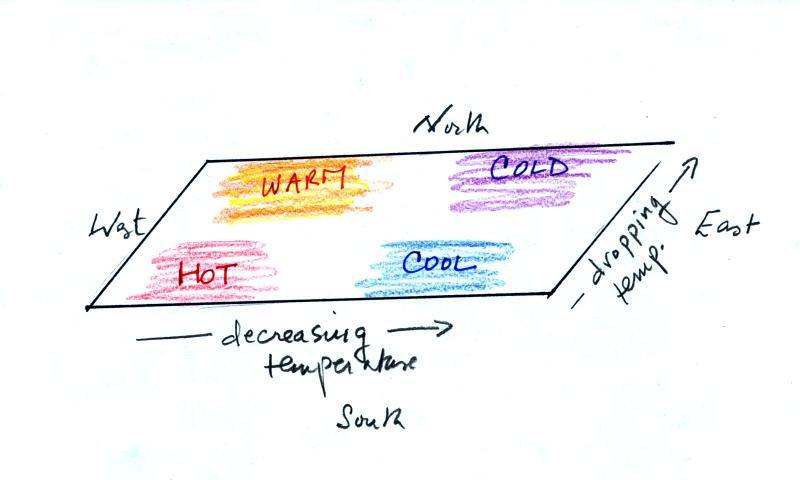

In the next figure we are going to add south to north temperature

changes in addition to the west to east temperature gradient.

Here's what the temperature pattern will look like.

Temperature drops as you move from west to east (as it did in the

previous pictures) and now it drops as you move from south to

north. What will the wavy 850 mb constant pressure surface

look like now? Click here

when you think you know (or if you just want to see the answer and

would rather not think about it).

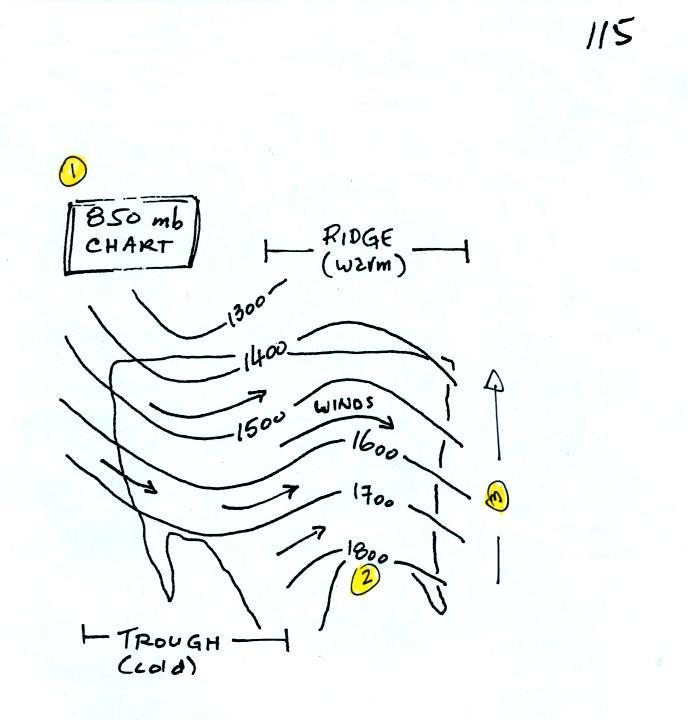

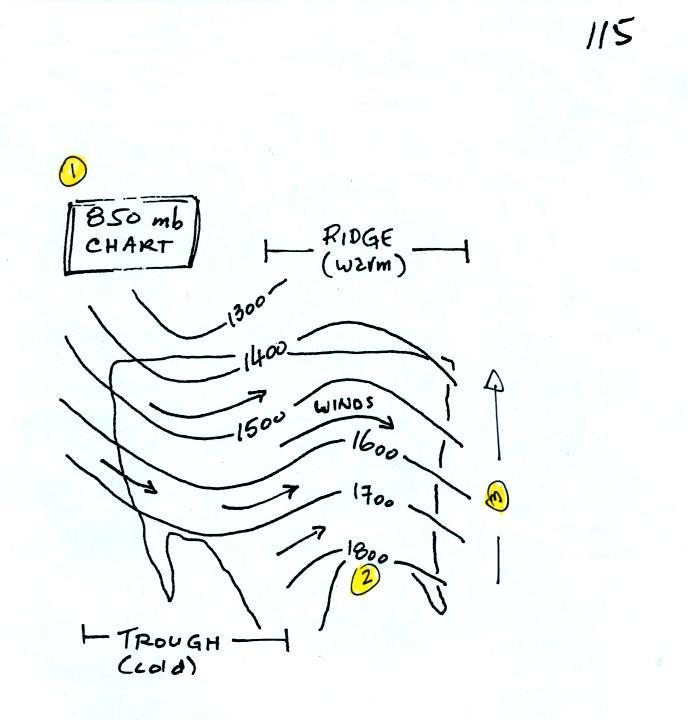

Now let's go back to the figure at the top of p. 115 in the

photocopied Classnotes.

1. The title tells you this is a map depicting the 850 mb

constant pressure level in the atmosphere.

2. Height contours are drawn on the chart. They show

the altitude, in meters, of the 850 mb pressure level at different

points on the map.

3. The numbers get smaller as you head north because the air

up north is colder. The 850 mb level is closer to the

ground.

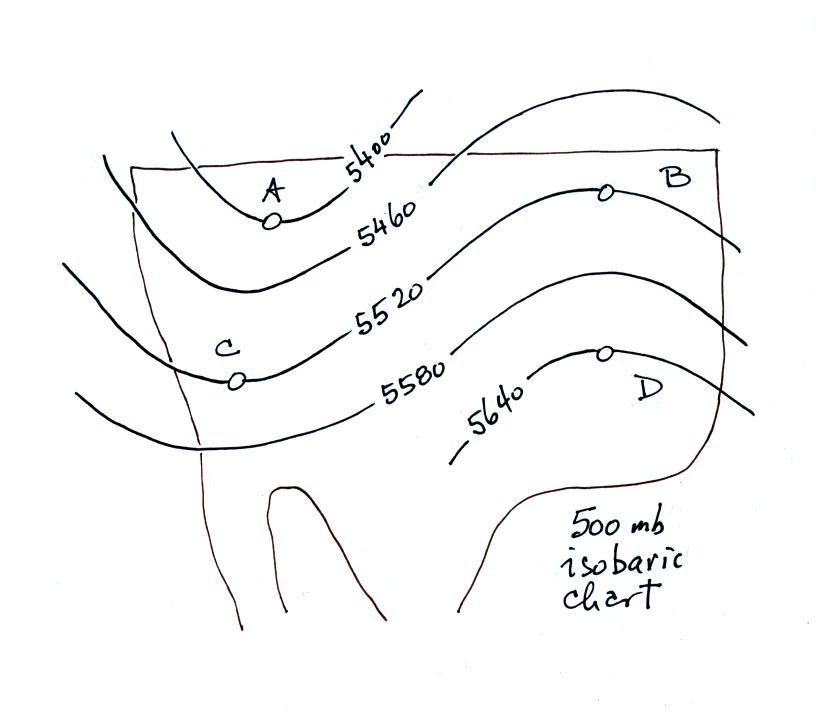

Here's

a figure with some questions to test your understanding of this

material.

This is a 500 mb constant pressure chart

not an 850 mb chart like in the previous examples.

Is the pressure at Point C greater

than, less than, or equal to the pressure at Point D (you can

assume that Points C and D are at the same latitude)? How do

the pressures at Points A and C compare?

Which of the four points (A, B, C, or D) is found at the lowest

altitude above the ground, or are all four points found at the

same altitude?

The coldest air would probably be found below which of the four

points? Where would the warmest air be found?

What direction would the winds be blowing at Point C?

Click here for all the answers.

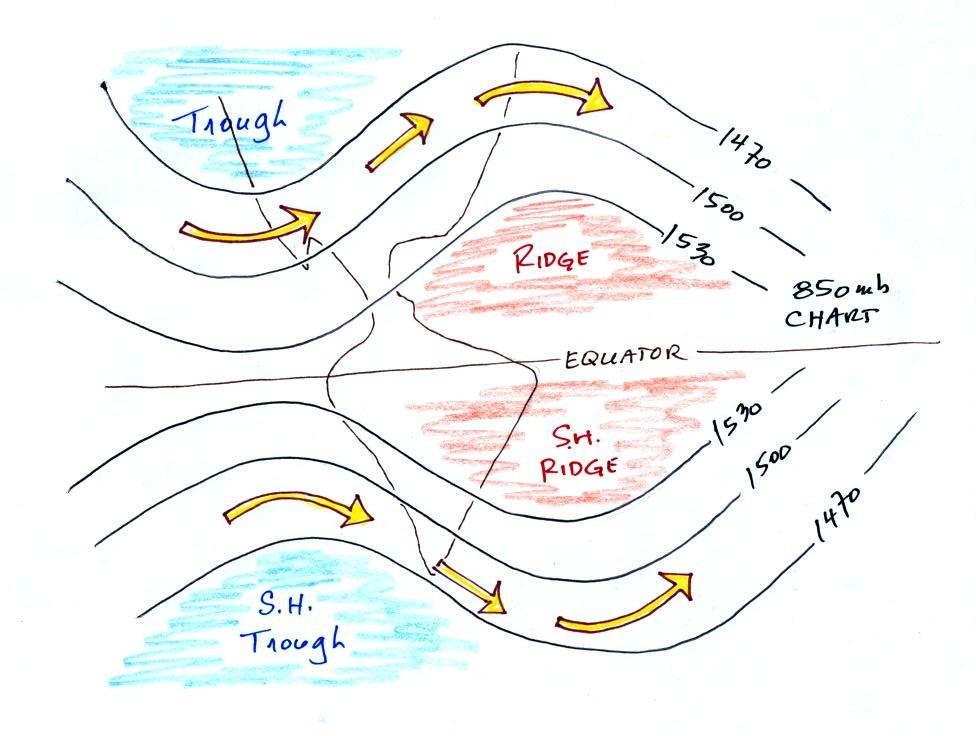

Finally

we will compare upper level charts in the northern and southern

hemisphere

The contour values get smaller as you move toward colder

air. The cold air is in the north in the northern hemisphere

and in the south in the southern hemisphere. The winds blow

parallel to the contour lines and from west to east in both

hemispheres.