click here to download today's notes in more

printer friendly Microsoft WORD format

You might have heard the faint sound of

music today

before class started. That was Roger

Clyne and the Peacemakers,

a group that I read about in the Arizona Daily Star this past weekend.

The humidity optional assignment was collected today. You'll get

a

detailed set of answers to the questions on that assignment in class on

Wednesday.

The Experiment #3 reports are due next Monday. You should try to

collect

your data as soon as you can, return the materials this week, and pick

up the

supplementary information sheet.

There are 2 or 3 sets of Experiment #4 materials that can be checked

out.

Today's class will be devoted entirely to

identifying

and naming clouds.

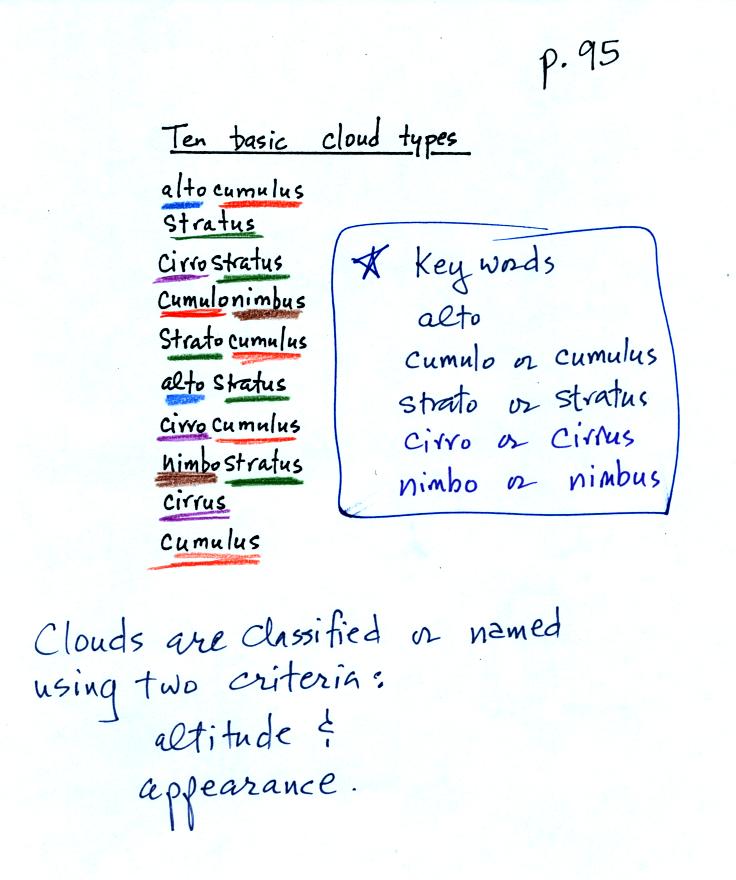

The ten main cloud types are listed below (you'll find this list on p.

95 in

the photocopied class notes).

You should try to learn these 10 cloud names. Not just because

they might

be on a quiz (they will) but because you will be able to impress your

friends

with your knowledge. There is a smart and a not-so-smart way of

learning

these names. The not-so-smart way is to just memorize them.

You

will inevitably get them mixed up. A better way is to recognize

that all

the cloud names are made up of key words. The key words, we will

find,

tell you something about the cloud altitude and appearance.

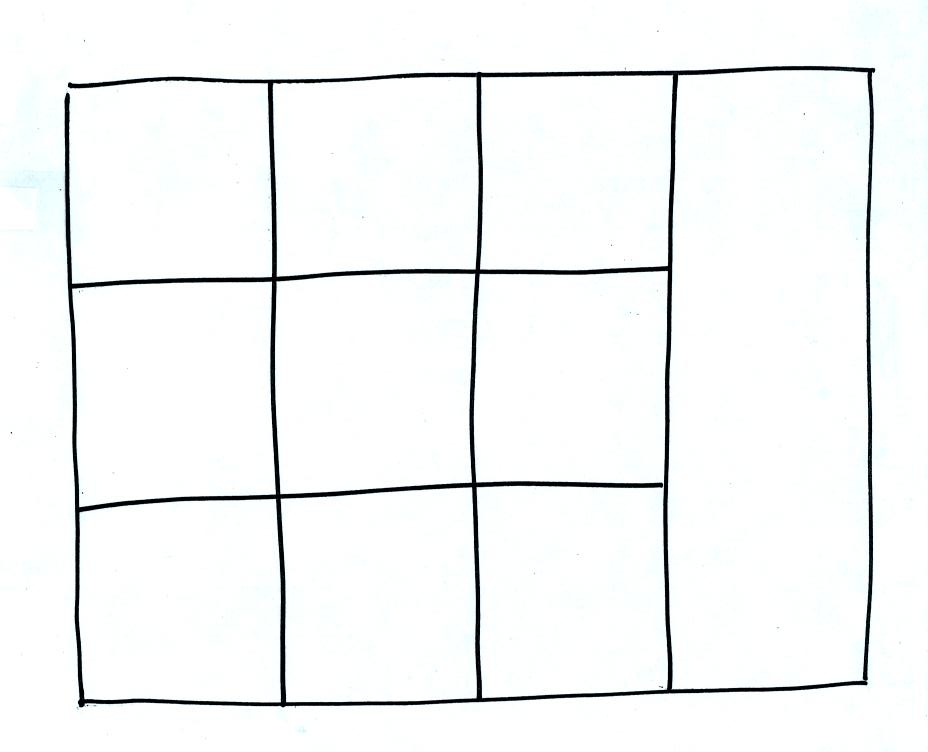

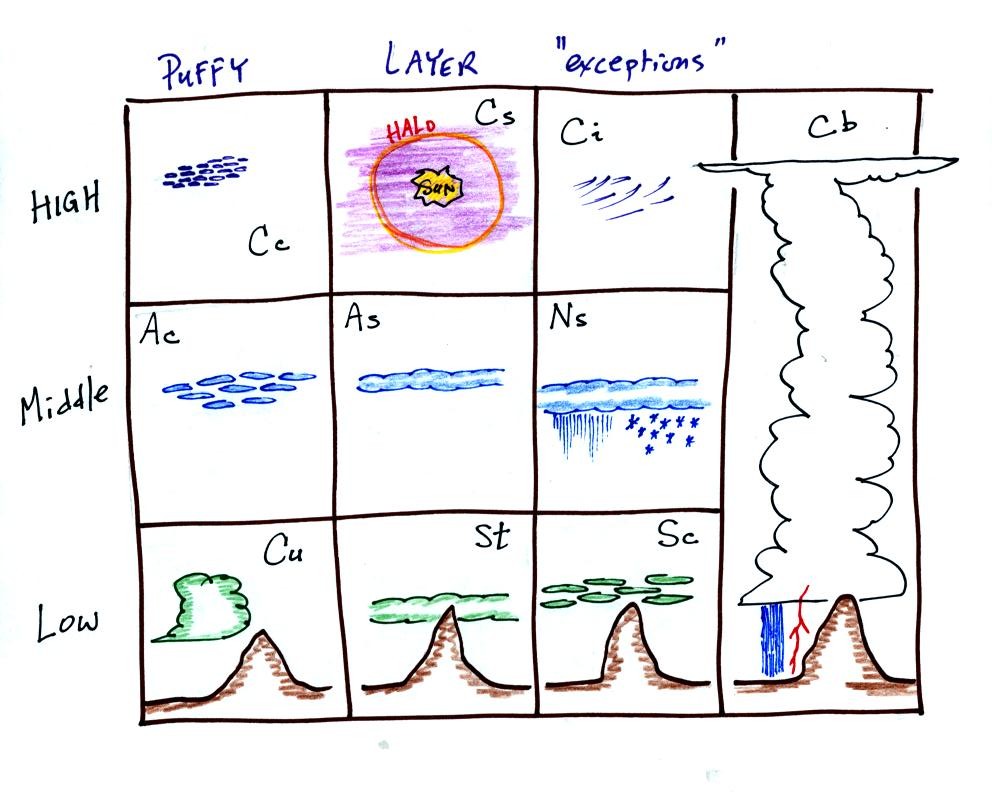

Drawing a figure like this on a blank sheet of paper is a good way to

review

cloud identification and classification.

Each of the clouds above has a box reserved for it in the figure.

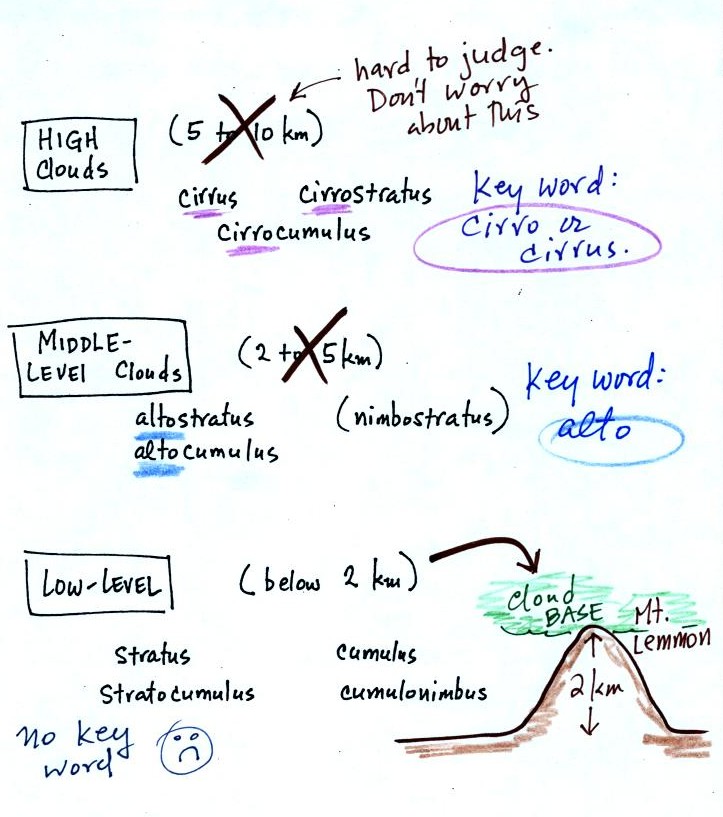

Clouds are classified according to the altitude at which they form and

the

appearance of the cloud. There are two key words for altitude and

two key

words for appearance.

Clouds are grouped into one of three altitude categories: high, middle

level,

and low.

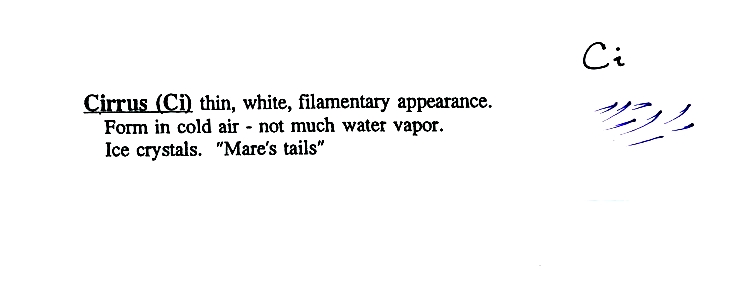

Cirrus or cirro identifies a high altitude

cloud. There are three types of clouds found in the high altitude

category..

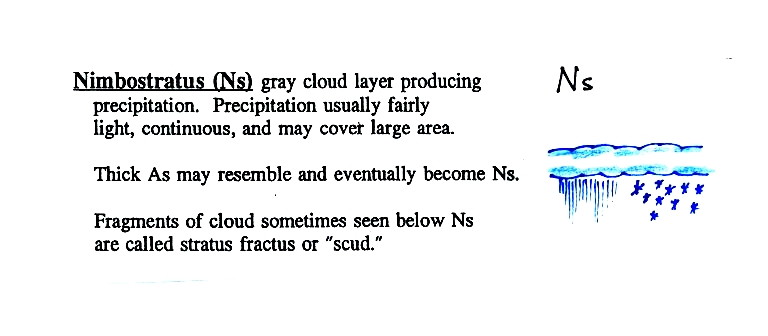

Alto in a cloud name means the cloud is found at middle altitude.

The

arrow connecting altostratus and nimbostratus indicates that they are

very

similar. When an altostratus cloud begins to produce rain or snow

its

name is changed to nimbostratus. A nimbostratus cloud is also

often somewhat

thicker and lower than an altostratus cloud.

It is very hard to just look up in the sky and determine a cloud's

altitude. You will need to look for other clues to distinquish

between high and middle altitude clouds. We'll learn about some

of the

clues when we look at cloud pictures later in the class.

There is no key word for low altitude clouds. Low altitude clouds

have

bases that form 2 km or less above the ground. The summit of

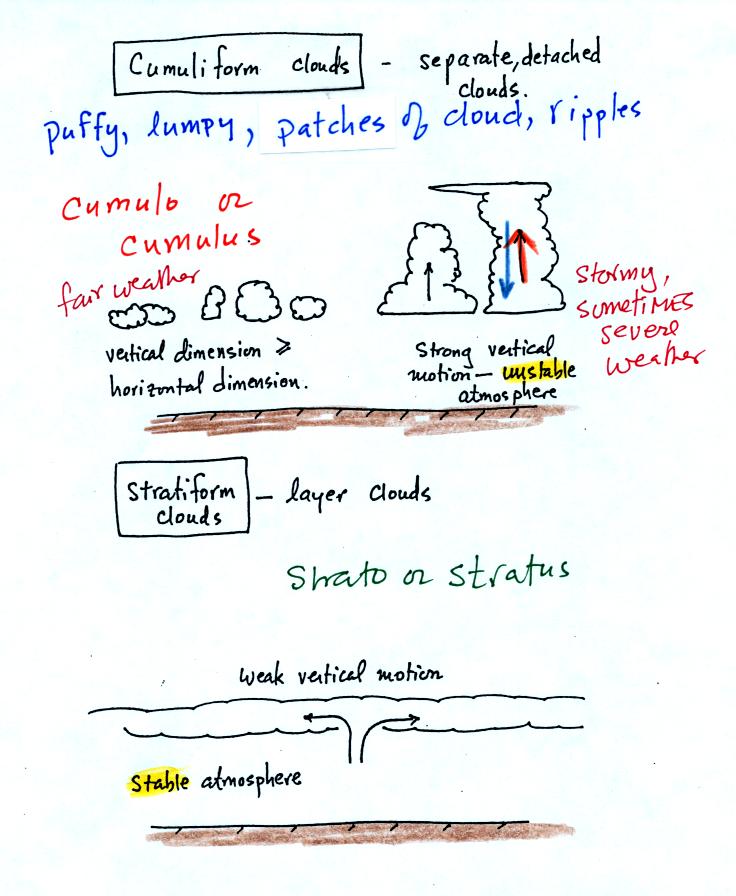

Now we will look at cloud appearance.

Clouds can have a patchy of puffy (or lumpy or wavy) appearance.

These

are cumuliform clouds and will have cumulo

or cumulus

in their name. In an unstable atmosphere cumuliform clouds will

grow vertically.

Stratiform clouds grow horizontally and

form

layers. They form when the atmosphere is stable.

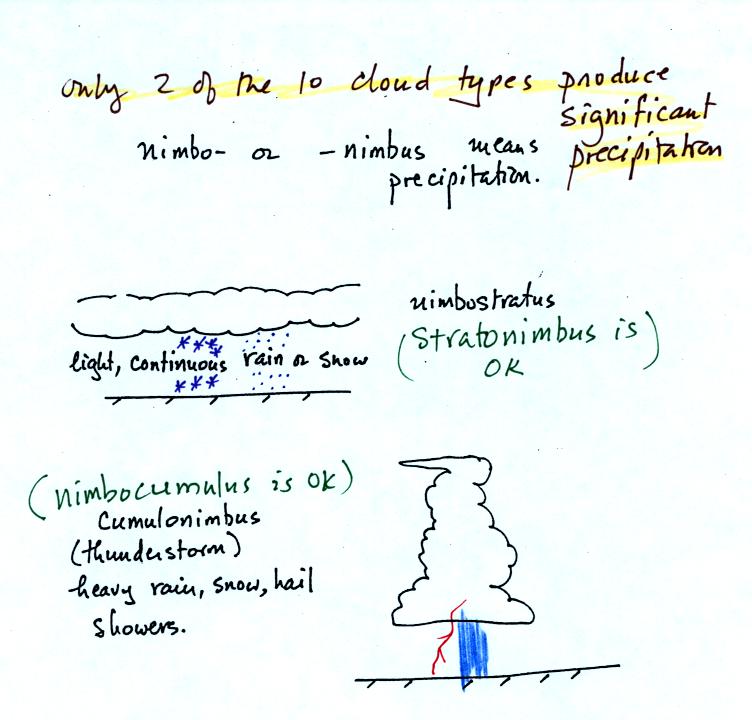

The last key word, nimbo or nimbus, means

precipitation. Two of the 10 cloud types are able to produce

(significant

amounts of) precipitation.

Nimbostratus clouds tend to produce fairly light precipitation over a

large

area. Cumulonimbus clouds produce heavy showers over localized

areas. Thunderstorm clouds can also produce hail, lightning, and

tornadoes. Hail would never fall from a

Ns

cloud.

While you are still learning the cloud names you might put the correct

key

words together in the wrong order (stratonimbus

instead of nimbostratus or nimbocumulus

instead of

cumulonimbus). You won't be penalized for those kinds of errors

in this

class.

Here's

the cloud chart from earlier. We've added the three altitude

categories

along the vertical side of the figure and the two appearance categories

along

the top. By the end of the class we will add a picture to each of

the

boxes.

Next

we looked at 35 mm slides of most of the 10 cloud types. There

are also

some good photographs in Chapter 6 in the text. You'll find the

written

descriptions of the cloud types in the images below on pps

97-98 in the photocopied notes.

High altitude

clouds

are thin

because the air at high altitudes is very cold and cold air can't

contain much

moisture (the saturation mixing ratio for cold air is very

small). These

clouds are also often blown around by fast high altitude winds.

Filamentary means "stringy" or "streaky". If you

imagine trying to paint a Ci cloud you

would dip a

small pointed brush in white paint brush it quickly and lightly across

a blue

colored canvas.

A

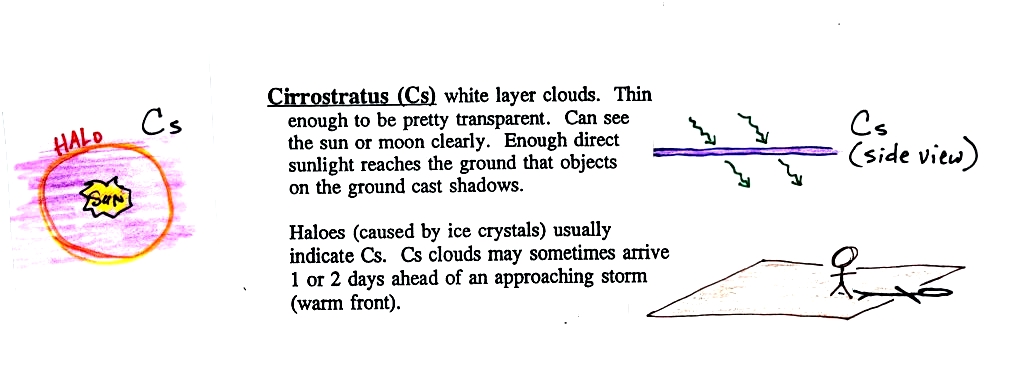

cirrostratus cloud is a thin uniform white layer cloud (not purple as

shown in

the figure) covering part or all of the sky. They're so thin you

can

sometimes see blue sky through the cloud layer. Haloes are a

pretty sure

indication that a cirrostratus cloud is overhead. If you were

painting Cs

clouds you could dip a broad brush in white paint (diluted perhaps with

water)

and then paint back and forth across the canvas.

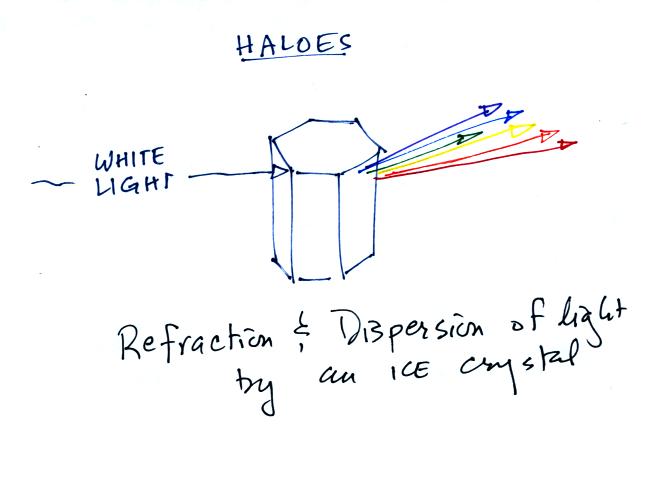

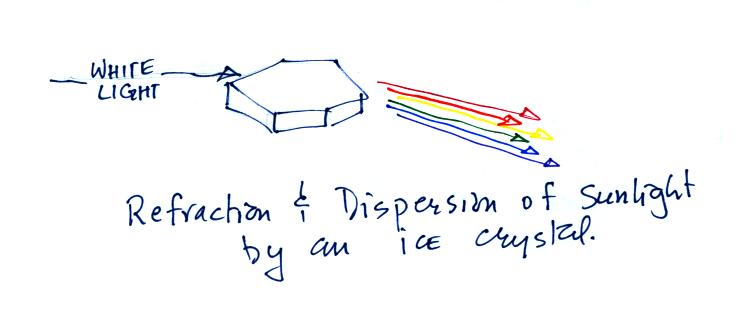

Haloes are

produced by

white light

entering a 6 sided ice crystal is bent (refraction). The amount

of

bending depends on the color (wavelength) of the light

(dispersion). The

white light is split into colors just as light passing through a glass

prism. This particular crystal is called a column and is fairly

long.

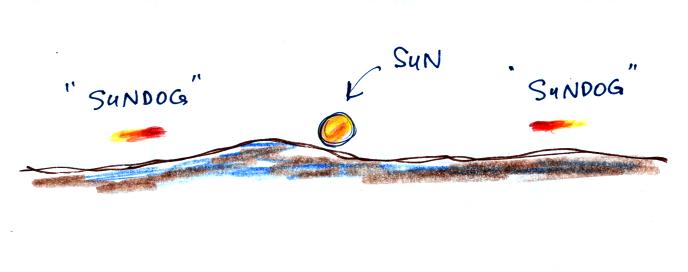

This is a flatter crystal and is called a plate. These crystals

tend to

all be horizontally oriented and produce sundogs. A sketch of a

sundog is

shown below.

Sundogs are

pretty

common and are

just patches of light seen to the right and left of the rising or

setting sun.

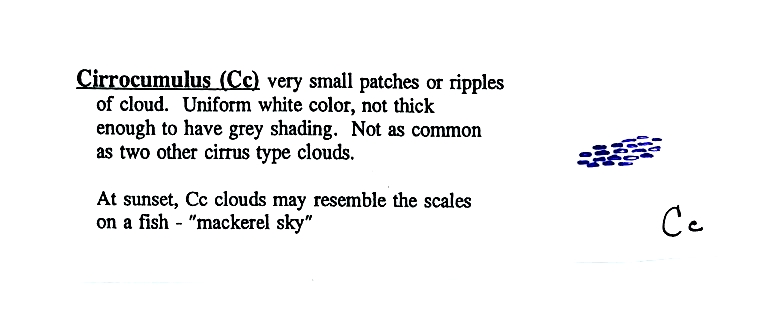

Cirrus and cirrostratus clouds are fairly common. Cirrocumulus

clouds are

a little more unusual.

To

paint a Cc cloud you would dip a sponge in white paint and press it

gently

against the canvas. You would leave a patchy, splotchy appearing

cloud

(sometimes you might see small ripples). It is the patchy (or

wavy)

appearance that makes it a cumuliform cloud.

If you spend enough time outside looking, you will see all of these

types of

clouds.

Though, it's like wild animals, some are much more common than others.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here are some animals that you are likely to see outdoors in the

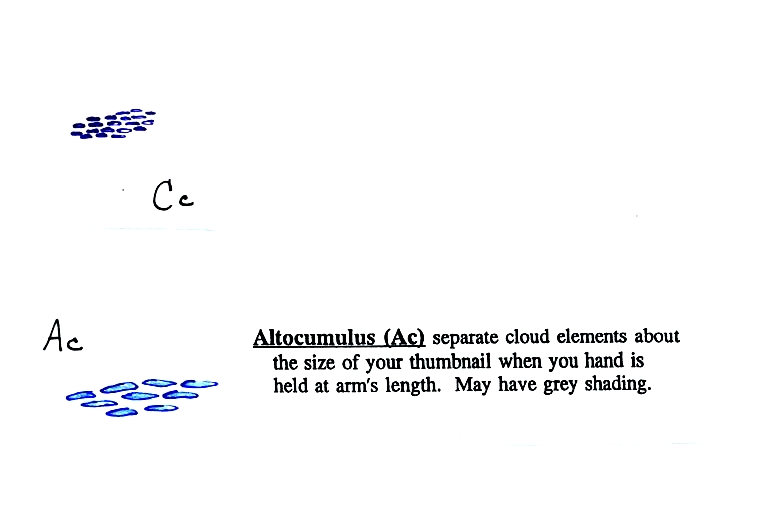

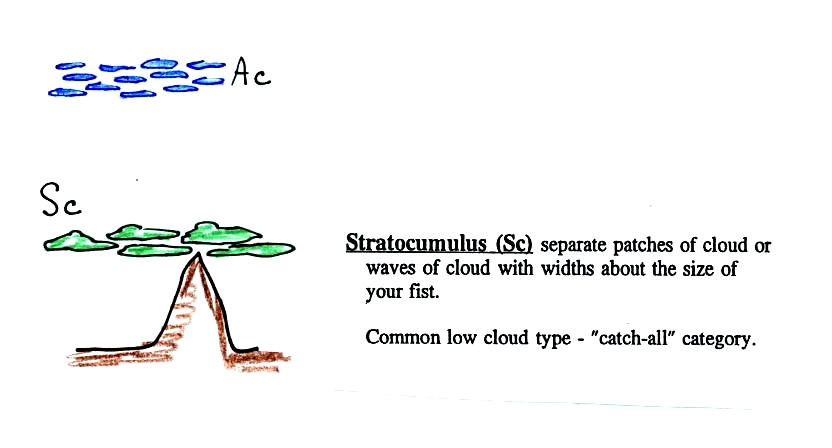

Altocumulus

clouds are pretty common. Note since it is

hard to

accurately judge altitude, you must rely on cloud element size

(thumbnail size

in the case of Ac) to determine whether a cloud belongs in the high or

middle

altitude category. The cloud elements in Ac clouds appear

larger

than in Cc because the cloud is closer to the ground.

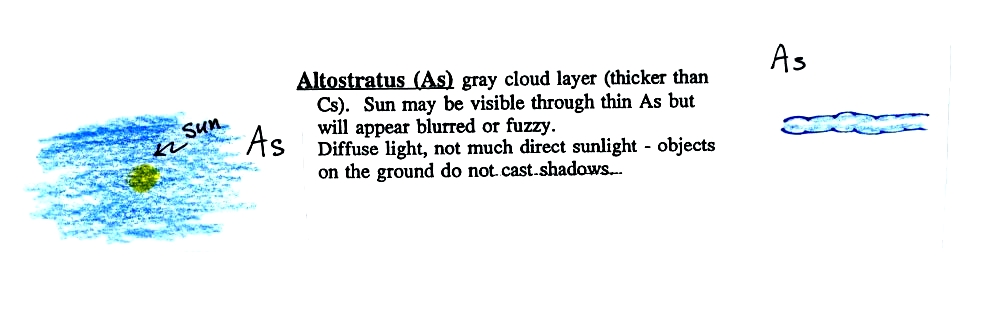

Altostratus

clouds are

thick

enough that you probably won't see a shadow if you look down at your

feet. The sun may or may not be visible through the cloud. When (if) an altostratus cloud begins to produce

precipitation, its

name is changed to nimbostratus.

This cloud name

is a

little

unusual because the two key words for cloud appearance have been

combined. Because they are closer to the ground, the separate

patches of

Sc are about fist size. The patches of Ac, remember, were about

thumb

nail size.

No pictures of

stratus

clouds were

shown in class.

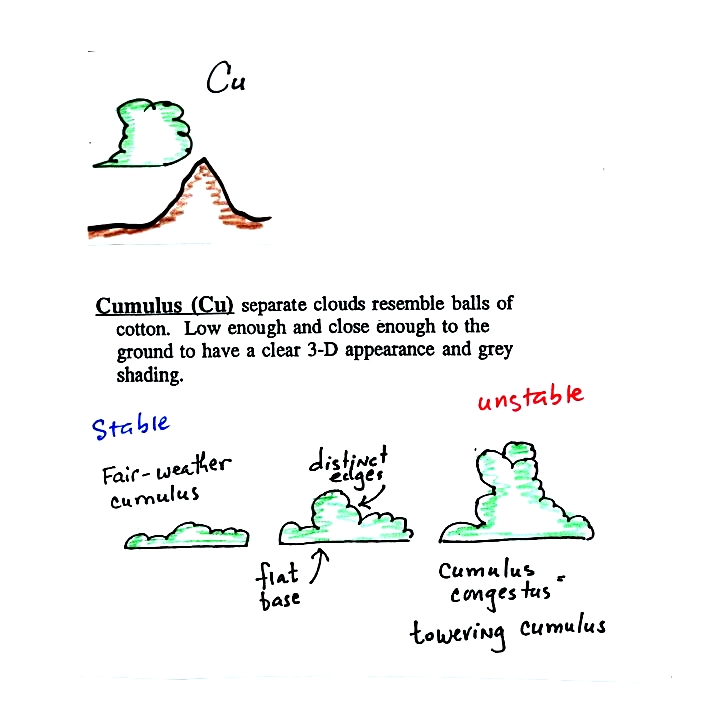

Cumulus clouds

come

with different

degrees of vertical development. The fair weather cumulus clouds

don't

grow much vertically at all. A cumulus congestus

cloud is an intermediate stage between fair weather cumulus and a

thunderstorm.

There are lots of

distinctive

features on cumulonimbus clouds including the flat anvil top and the

lumpy mammatus clouds sometimes found on

the underside of the

anvil. Cold dense downdraft winds hit the ground below a

thunderstorm and

spread out horizontally underneath the cloud. The leading edge of

these

winds produces a gust front (dust front might be a little more

descriptive).

Winds at the ground below a thunderstorm can exceed 100 MPH, stronger

than many

tornadoes. The top of a thunderstorm is cold enough that it will

be

composed of just ice crystals. The bottom is composed of water

droplets. In the middle of the cloud both water droplets and ice

crystals

exist together at temperatures below freezing (the water droplets have

a hard

time freezing). Water and ice can also be found together in

nimbostratus

clouds. We will see that this mixed phase region of the cloud is

important

for precipitation formation. It is also where the electricity

that

produces lightning is generated.

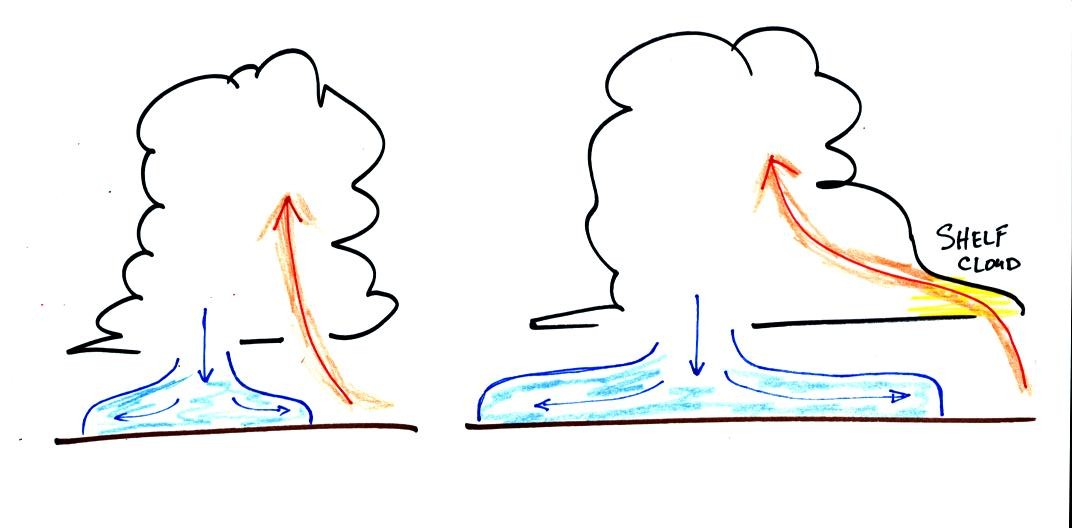

Here's one final feature to look for at the bottom of a

thunderstorm.

Cold air spilling

out

of the base

of a thunderstorm is just beginning to move outward from the bottom

center of

Here's the completed cloud chart.