Tuesday Sep. 30, 2014

Time for 4 songs from Dessa before class. You heard "551",

"Call Off

Your Ghosts", "Skeleton

Key", and "Mineshaft

II". I

stumbled on a 1 hour concert yesterday that I didn't have much

time to listen to with a lot more songs. You can listen

to it here

if you're so inclined.

Quiz #1 has been graded and was returned in

class today. The average score was 72% which is a little

low (but slightly higher than the other section of the

class). Be sure to carefully check the grading and that

the points were added up correctly. Also be sure to hang

on to any papers that are returned to you (quizzes, 1S1P

reports, etc) until you have received your final grade in the

class.

There were some very high grades. If you were part of

that group remember there are three more quizzes before the

end of the semester. Pace yourself and keep up the good

work. And don't forget that the writing, both the

experiment and 1S1P reports, gets averaged in with the quiz

scores.

Your lowest quiz score gets dropped unless you're trying to

get out of the final exam. So it is possible that a low

score on this quiz won't have any effect at all on your final

grade. It is important to figure out why you didn't do

better on this first quiz. Often it is a case of not

keeping up with the class and trying to cram a lot of studying

into the last day or two before a quiz. You should be

reading the notes as soon as they appear online after class.

An In-class

Optional Assignment was handed out and collected at the

end of today's class. If you weren't in class but are

reading these online notes you can download the assignment if

you want to and turn in the questions at the beginning of

class on Thursday.

Quiz grading gets priority over the 1S1P reports. Now

that the quiz is behind us we'll get back to work on the 1S1P

reports. I hope to return graded Experiment #1 reports

in class on Thursday.

Before the quiz we learned how weather data and

observations are plotted on a surface weather map. Next

we'll start to see what analysis of that data can start

to tell you about the weather.

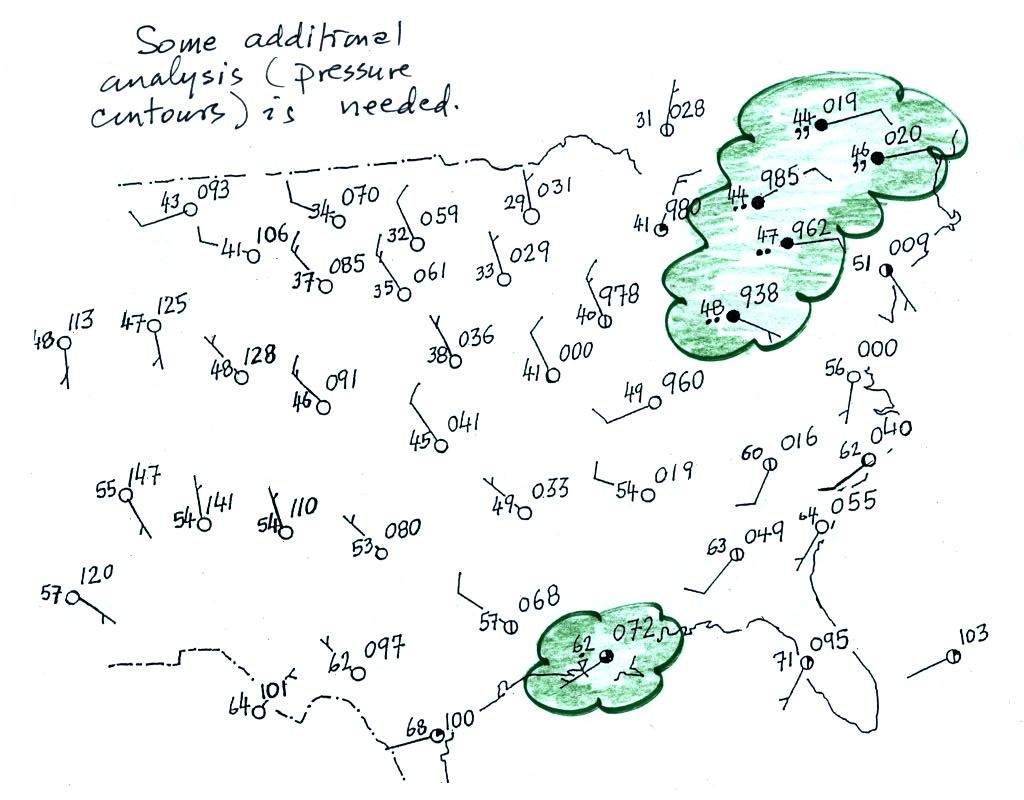

A bunch of weather data has been plotted

(using the station model notation) on the surface weather

map in the figure below (p. 38 in the ClassNotes).

Plotting the surface weather data on a map is just

the beginning. For example you really can't tell what is

causing the cloudy weather with rain (the dot symbols are

rain) and drizzle (the comma symbols) in the NE portion of the

map above or the rain shower along the Gulf Coast. Some

additional analysis is needed.

1st step in surface map

analysis: draw in some contour lines to reveal the large

scale pressure pattern

Pressure

contours = isobars

( note the word bar is in millibar, barometer, and now

isobar )

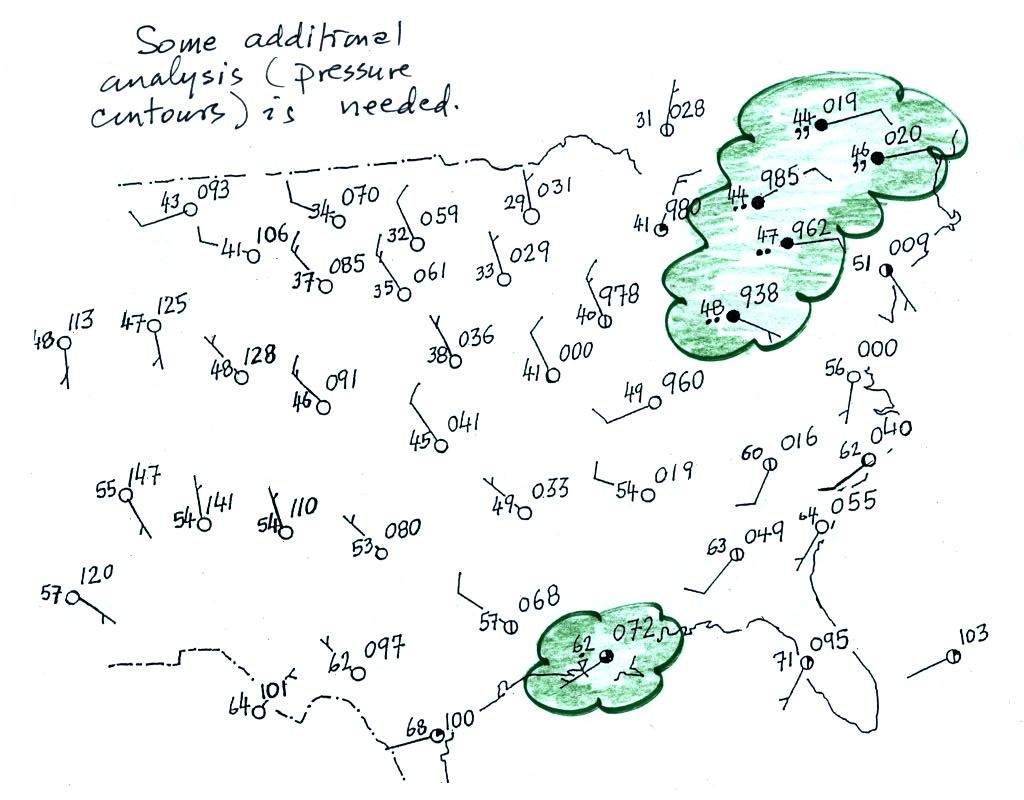

Temperature contours = isotherms

A meteorologist would usually begin by drawing some

contour lines of pressure (isobars) to map out the large scale

pressure pattern. We will look first at contour lines of

temperature, they are a little easier to understand (the

plotted data is easier to decode and temperature varies across

the country in a more predictable way).

Isotherms

Isotherms, temperature contour lines, are usually drawn at 10o F intervals. They

do two things:

isotherms (1) connect points on the map

with the same temperature

(2) separate

regions warmer

than a particular temperature

from regions colder

than a particular temperature

The 40o F isotherm

above passes through a city which is reporting a temperature of

exactly 40o (Point A).

Mostly it goes between pairs of cities: one with a temperature

warmer than 40o (41o at

Point B) and the other colder than 40o (38o

F at Point C). The temperature pattern is also

somewhat more predictable than the pressure pattern: temperatures

generally decrease with increasing latitude: warmest temperatures

are usually in the south, colder temperatures in the north.

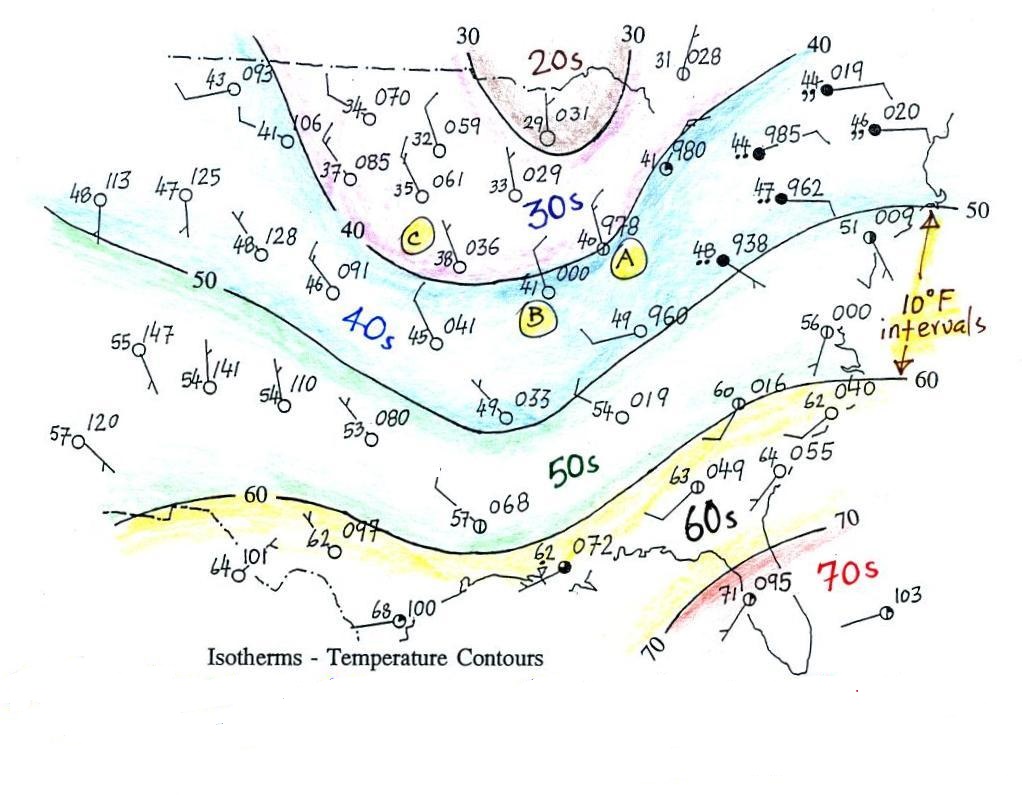

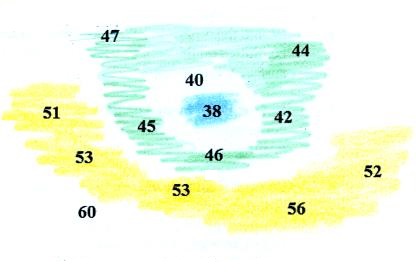

A figure similar to Question #1 on the In-class Optional

Assignment is shown below at far left. We'll draw in 40 F

and 50 F isotherms. Colors can help you do this. In

the center picture temperatures below 40 are colored blue,

temperature between 40 and 50 are green and temperatures in the

50s are colored yellow.

The isotherms have been drawn in at right and separate

the colored bands. Note how the 40 F isotherm goes through

the 40 on the map.

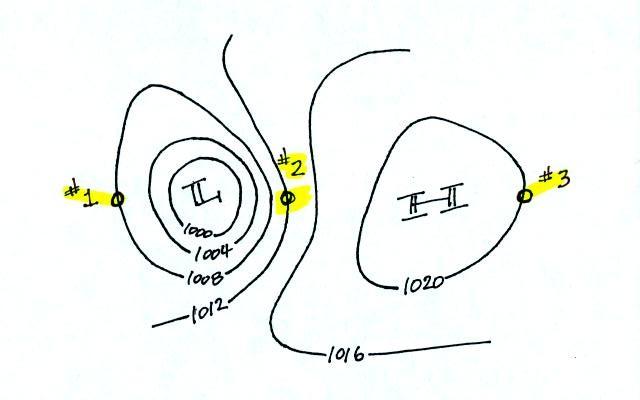

Isobars

isobars (1) connect points on the map with equal pressure

(2)

separate regions of high

pressure from regions with lower

pressure

identify

and locate centers of high and low pressure

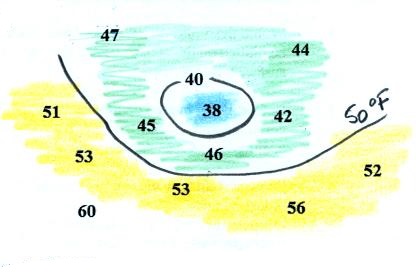

Here's the same weather map with isobars drawn in.

Isobars are generally drawn at 4 mb intervals (above and below a

starting value of 1000 mb).

The 1008 mb isobar (highlighted in yellow) passes through a city

at Point A where the

pressure is exactly 1008.0 mb. Most of the time the isobar

will pass between two cities. The 1008 mb isobar passes

between cities with pressures of 1009.7 mb at Point B and 1006.8 mb at Point C. You would

expect to find 1008 mb somewhere in between those two cites, that

is where the 1008 mb isobar goes.

The isobars separate regions of high and low pressure.

The pressure pattern is not as predictable as the isotherm

map. Low pressure is found on the eastern half of this map

and high pressure in the west. The pattern could just as

easily have been reversed.

This

site (from the American Meteorological Society) first shows

surface weather observations by themselves (plotted using the

station model notation) and then an analysis of the surface data

like what we've just looked at. There are links below each

of the maps that will show you current surface weather data.

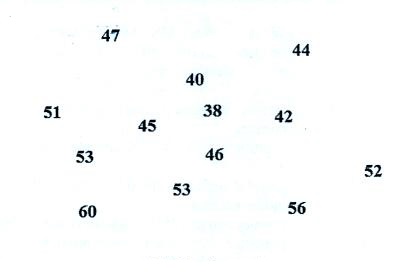

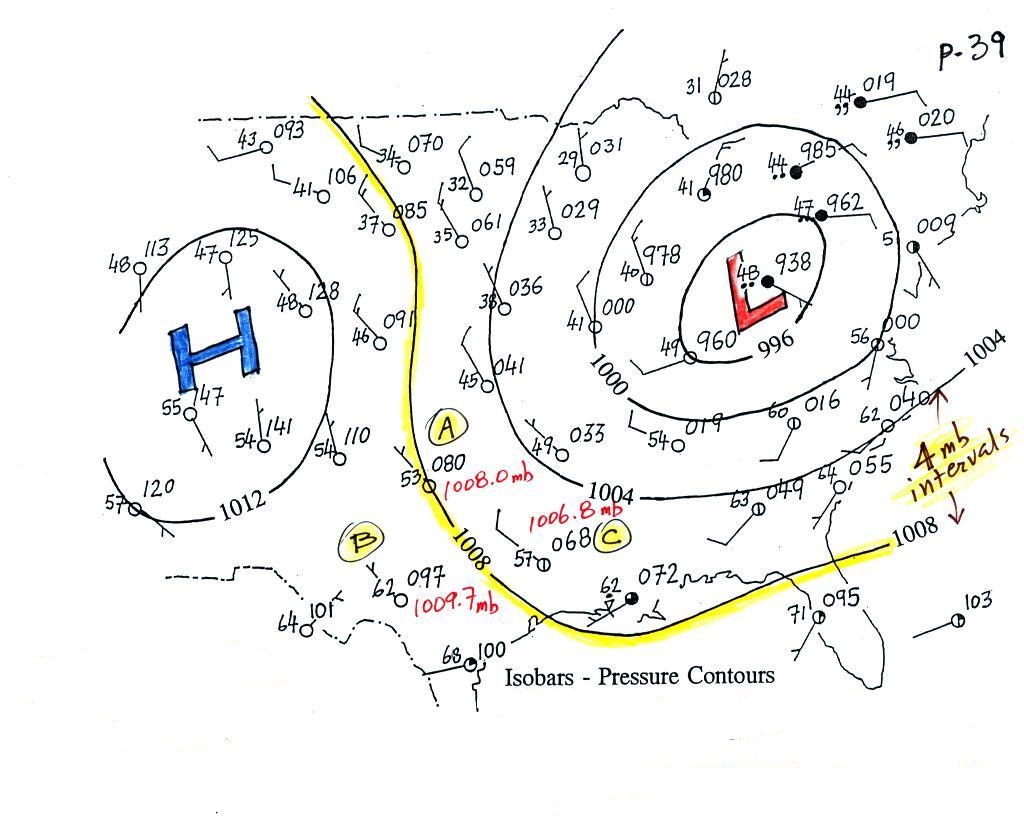

Here's a little practice (this figure wasn't shown in

class).

A single isobar is shown. Is it the 1000, 1002, 1004, 1006,

or 1008 mb isobar? (you'll find the answer at the end of today's

notes)

What can you begin to learn about the weather once you've

mapped out the pressure pattern?

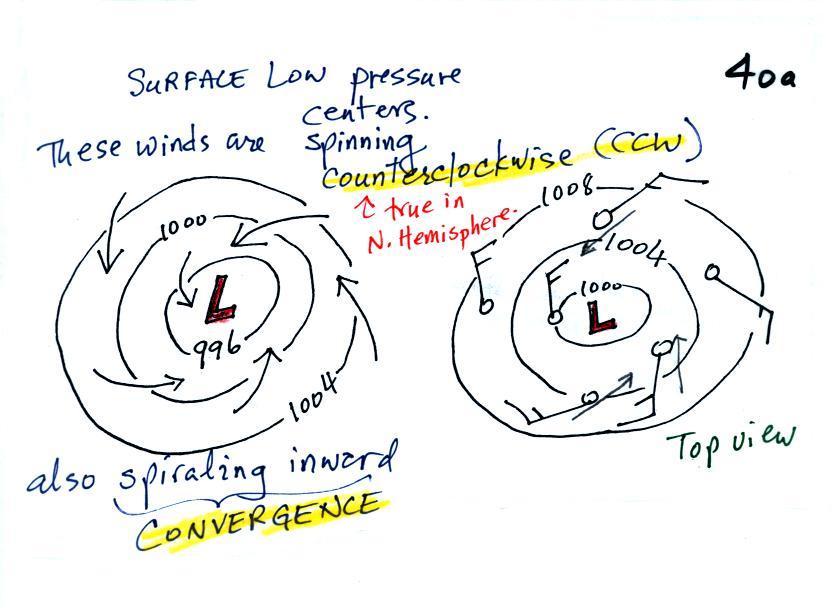

1. Surface centers of low pressure

We'll start with the large nearly circular centers of High and

Low pressure. Low pressure is drawn below. These

figures are more neatly drawn versions of what we did in class.

Air will start moving toward low

pressure (like a rock sitting on a hillside that starts to roll

downhill), then something called the Coriolis force will cause

the wind to start to spin (I didn't

mention the Coriolis force in class, we'll learn

more about it later in the semester).

In the northern hemisphere winds spin in a counterclockwise

(CCW) direction around surface low pressure centers. The

winds also spiral inward toward the center of the low, this is

called convergence. [winds spin clockwise around low

pressure centers in the southern hemisphere but still spiral

inward, don't worry about the southern hemisphere until later in

the semester]

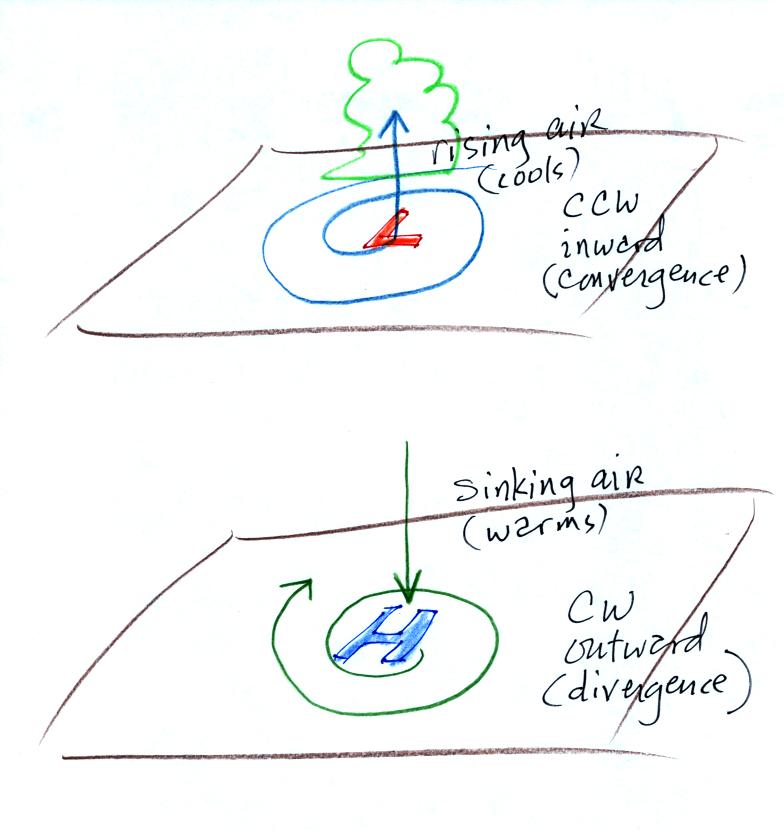

When the converging air reaches the center of the low it starts to

rise.

Convergence causes

air to rise

rising air

e-x-p-a-n-d-s (it

moves into lower pressure surroundings at higher

altitude)

The expansion causes the air to cool

If you cool moist air enough (to or below

its dew point temperature) clouds can form

Convergence is 1 of 4 ways of causing air to rise (we'll

learn what the rest are soon, and, actually, you already know what

one of them is - warm air rises, that's called convection). You often see cloudy

skies and stormy weather associated with surface low pressure.

Everything is pretty much the exact opposite in the case

of surface high pressure.

Winds spin clockwise (counterclockwise in the southern

hemisphere) and spiral outward. The outward motion is called

divergence.

Air sinks in the center of surface high pressure to

replace the diverging air. The sinking air is compressed and

warms. This keeps clouds from forming so clear skies are

normally found with high pressure.

Clear skies doesn't necessarily mean warm weather, strong surface

high pressure often forms when the air is very cold.

Here's a picture summarizing what we've learned so far.

It's a slightly different view of wind motions around surface

highs and low that tries to combine all the key features in as

simple a sketch as possible.

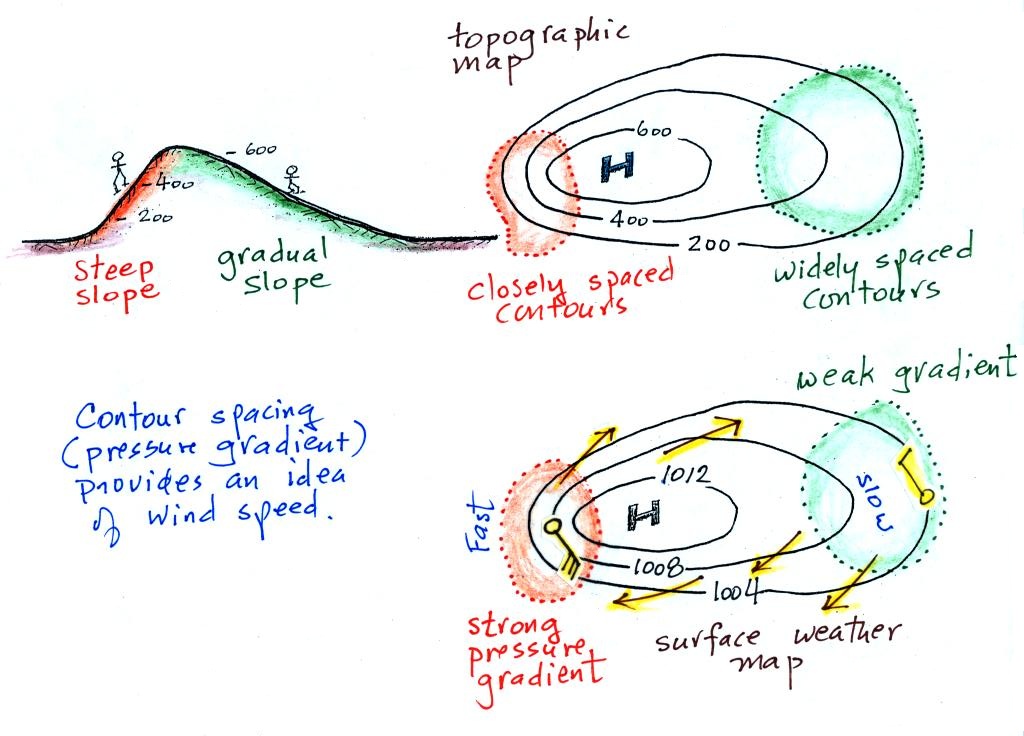

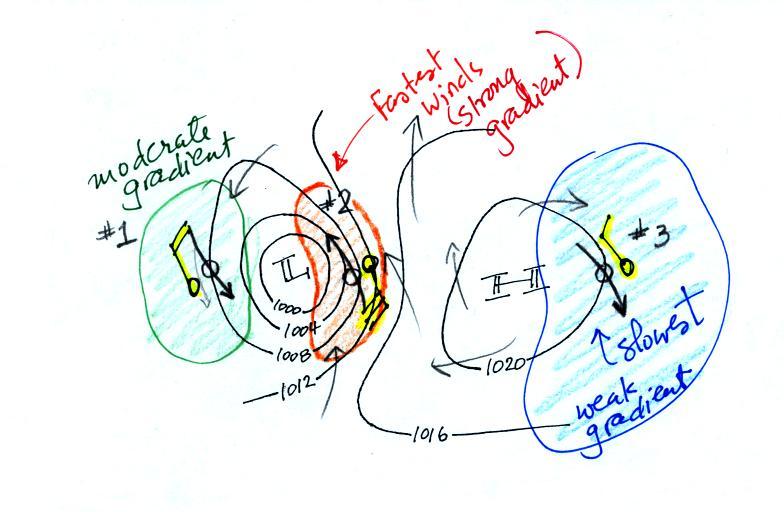

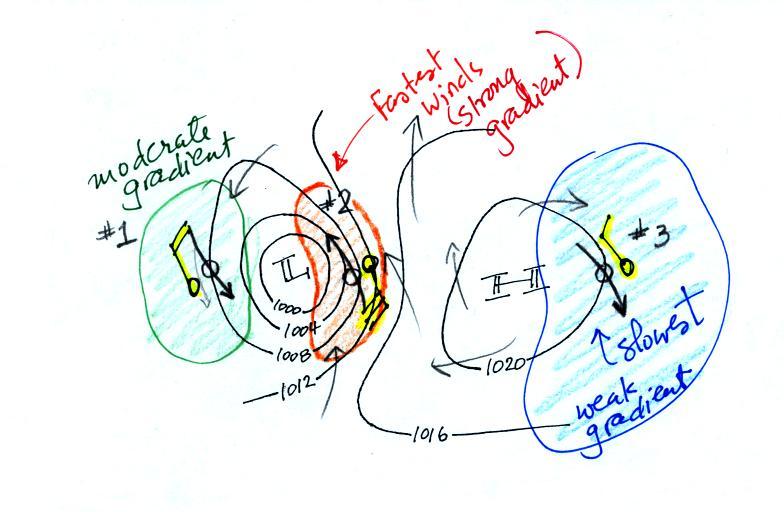

2. Strong and weak

pressure gradients

The pressure pattern will also tell you something about where

you might expect to find fast or slow winds. In this case

we look for regions where the isobars are either closely spaced

together or widely spaced. Portions of the two figures

that follow can be found on p. 40c in the ClassNotes.

A picture of a hill is shown above at left. The map at

upper right is a topographic map that depicts the hill

(the numbers on the contour lines are altitude). A center of

high pressure on a weather map, the figure at the bottom,

has the same overall appearance. The numbers on the contours

are different. These are contours (isobars) of pressure

values in millibars.

Closely spaced contours on a topographic map indicate a steep

slope. More widely spaced contours mean the slope is more

gradual. If you roll a rock downhill on a steep

slope it will roll more quickly than if it is on a gradual

slope. A rock will always roll downhill, away from the

summikt in this case toward the outer edge of the topographic map.

On a weather map, closely spaced contours (isobars) means pressure

is changing rapidly with distance. This is known as a strong

pressure gradient and produces fast winds (a 30 knot wind blowing

from the SE is shown in the orange shaded region above).

Widely spaced isobars indicate a weaker pressure gradient and the

winds would be slower (the 10 knot wind blowing from the NW in the

figure).

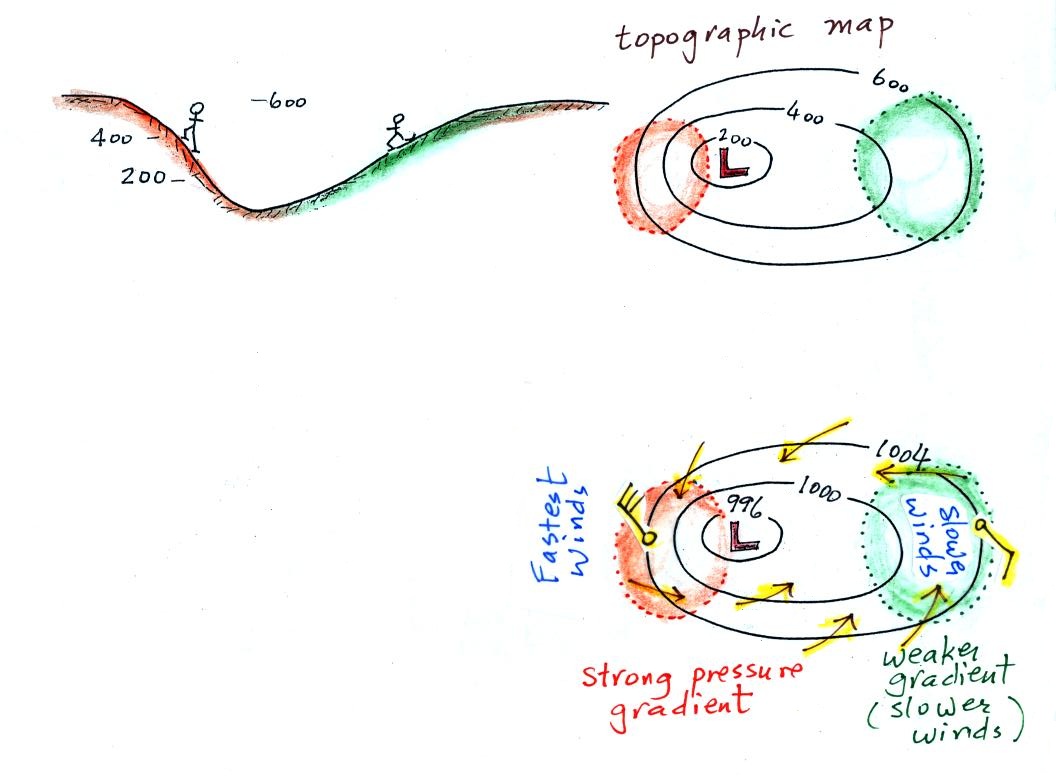

Winds spin counterclockwise and

spiral inward around low pressure centers. The fastest

winds are again found where the pressure gradient is strongest.

Contour spacing

closely

spaced isobars = strong pressure gradient

(big change in pressure with distance) - fast

winds

widely spaced isobars = weak

pressure gradient (small change in pressure

with distance) - slow winds

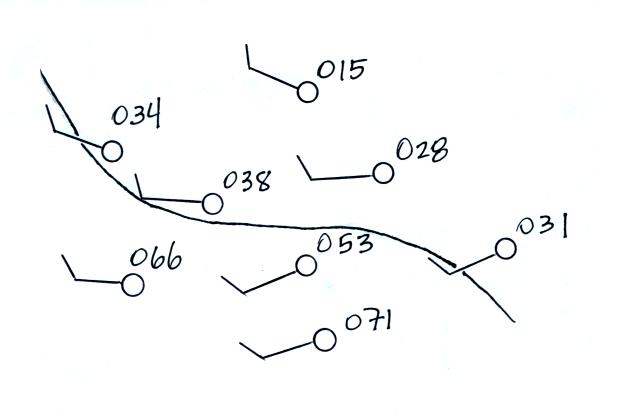

This figure is found at the bottom of p. 40 c in the

photocopied ClassNotes. You should be able to sketch in the

direction of the wind at each of the three points and determine

where the fastest and slowest winds would be found. (you'll find

the answer at the end of today's notes).

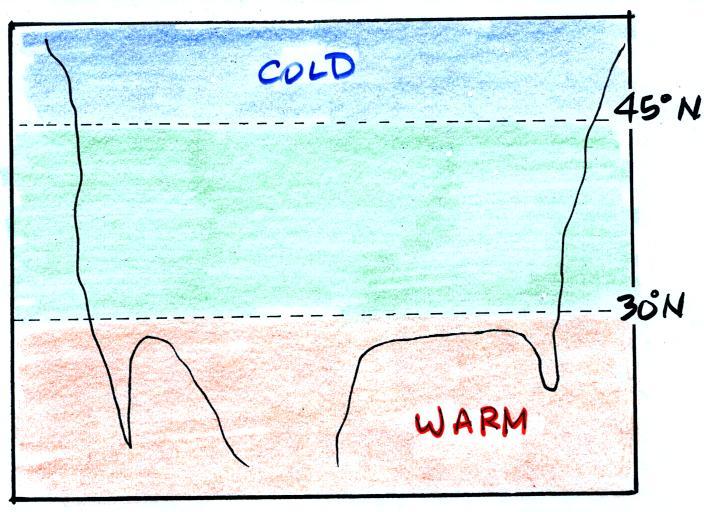

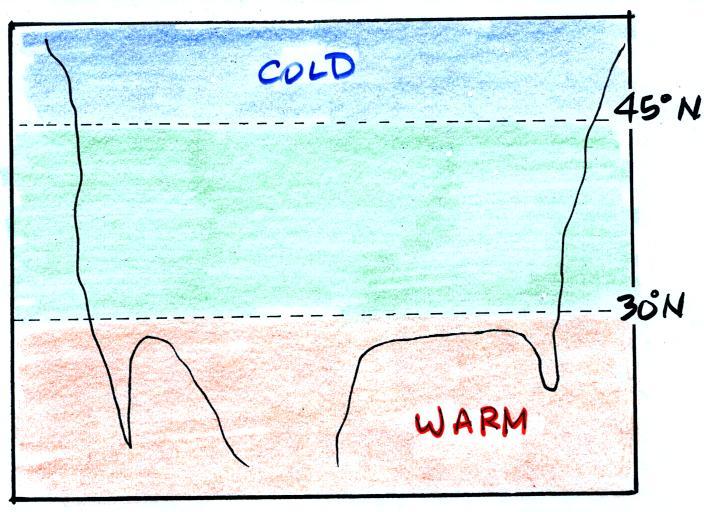

3. Temperature patterns and fronts

The pressure pattern causes the wind to start to

blow; the wind then can affect and change the temperature

pattern. The figure below shows the temperature

pattern you would expect to see if the wind wasn't blowing at all

or if the wind was just blowing straight from west to east.

The bands of different temperature are aligned parallel to the

lines of latitude. Temperature changes from south to north

but not from west to east.

This picture gets a

little more interesting if you put centers of high or low

pressure in the middle.

In the case of high pressure,

the clockwise spinning winds move warm air to the north on the

western side of the High. The front edge of this

northward moving air is shown with a dotted line (at Pt. W) in

the picture above. Cold air moves toward the south on

the eastern side of the High (another dotted line at Pt.

C). The diverging winds also move the warm and cold air

away from the center of the High. Now you would

experience a change in temperature if you traveled from west

to east across the center of the picture.

The transition from warm to cold along the boundaries (Pts.

W and C) is spread out over a fairly long distance and is

gradual. This is because the winds around high pressure

diverge and blow outward away from the center of high

pressure. There is also some mixing of the different

temperature air along the boundaries.

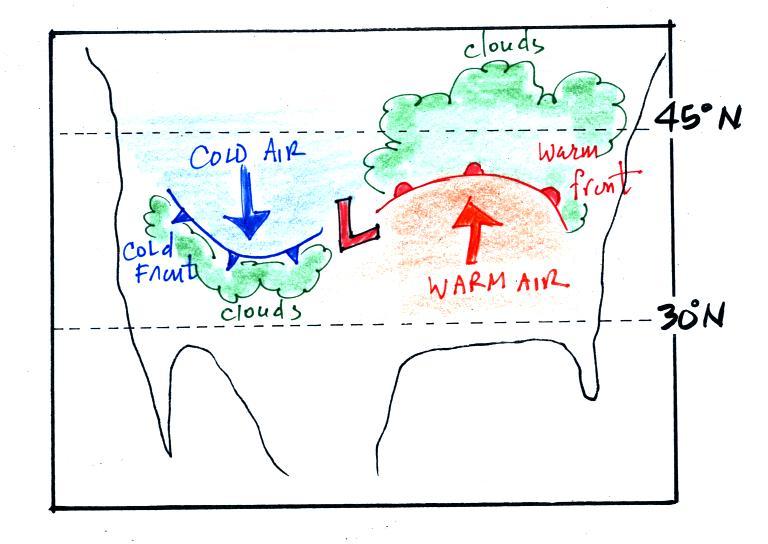

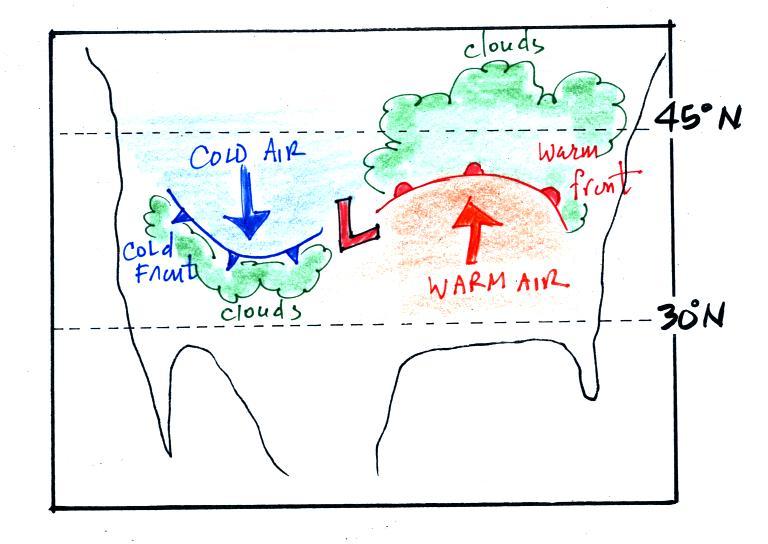

Counterclockwise winds move cold air toward the south on the

west side of the Low. Warm air advances toward the north

on the eastern side of the low. This is just the opposite

of what we saw with high pressure.

The converging winds in the case of low pressure will move

the air masses of different temperature in toward the center of

low pressure. The transition zone between different

temperature air gets squeezed and compressed. The change

from warm to cold occurs in a shorter distance and is sharper

and more distinct. Solid lines have been used to delineate

the boundaries above. These sharper and more abrupt boundaries

are called fronts.

A cold front is drawn at the front edge of

the southward moving mass of cold air on the west side of the

Low. Cold fronts are generally drawn in blue on a surface

weather map. The small triangular symbols on the side of the

front identify it as a cold front and show what direction it is

moving.

A warm front (drawn in red with half circle symbols) is shown

on the right hand side of the map at front edge of the northward

moving mass of. A warm front is usually drawn in red and has

half circles on one side of the front to identify it and show its

direction of motion.

The fronts are like spokes on a wheel. The "spokes" will

spin counterclockwise around the low pressure center (the axle).

Both types of fronts cause rising air motions. Fronts are

another way of causing air to rise. That's important because

rising air expands and cools. If the air is moist and cools

enough, clouds can form.

The storm system shown in the picture above (the Low together with

the fronts) is referred to a middle latitude storm or an

extra-tropical cyclone. Extra-tropical means outside the

tropics, cyclone means winds spinning around low pressure

(tornadoes are sometimes called cyclones, so are

hurricanes). These storms form at middle latitudes because

that is where air masses coming from the polar regions to the

north and the more tropical regions to the south can collide.

Large storms that form in the tropics (where this mostly just warm

air) are called tropical cyclones or, in our part of the world,

hurricanes.

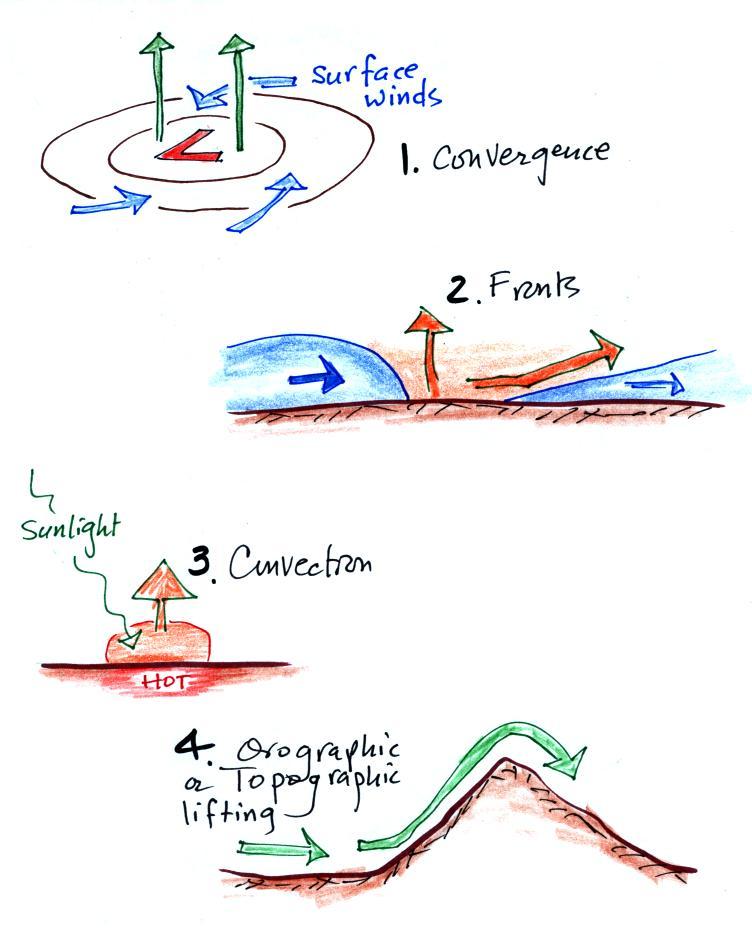

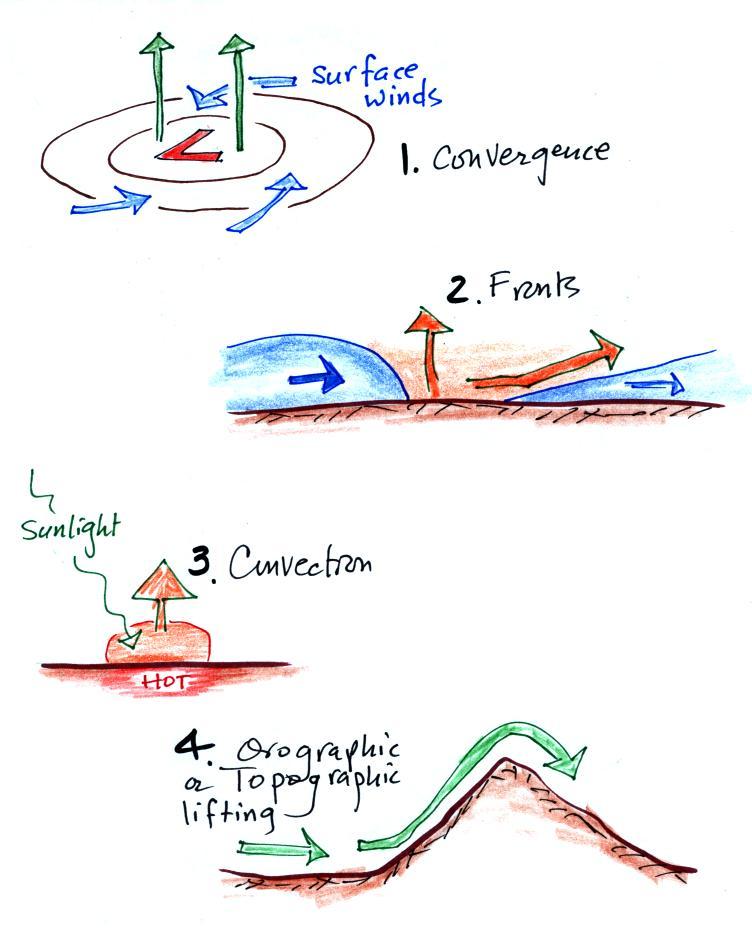

Fronts are a 2nd (or 3rd way) of causing air to

rise. Do you remember the other 1 (or 2)? There

are a total of 4 processes that cause air to rise. They are

all sketched below. This

figure wasn't shown in class.

1. Convergence, winds spiraling in toward centers of low

pressure was mentioned earlier in class.

2. Fronts we've just learned cause air to rise. The two

fronts are shown in crossection above. You'll better

understand what is going on here after class on Thursday.

3. Sunlight striking and being absorbed at the ground warms the

ground. Air in contact with the ground warms and becomes

buoyant. If it is warm enough (low enough density) it will

float upward on its own. This is called free convection.

4. Finally when winds encounter a mountain they must move upward

and over the mountain. You might expect to see clouds and

precipitation on the upwind side of the mountain because that is

where the air is rising and cooling. You'll sometimes find a

"rainshadow" (lack of rain) on the dry downslope side of a

mountain.

Here are answers to the two questions embedded in today's notes

Pressures lower than 1002 mb are colored purple.

Pressures between 1002 and 1004 mb are blue. Pressures

between 1004 and 1006 mb are green and pressures greater than 1006

mb are red. The isobar appearing in the question is

highlighted yellow and is the 1004 mb isobar. The 1002 mb

and 1006 mb isobars have also been drawn in (because isobars are

drawn at 4 mb intervals starting at 1000 mb, the 1002 mb and 1006

mb isobars wouldn't normally be drawn on a map)

Winds from the NW at 20 knots at Point #1,

SE winds at 30 knots at Point #2, and NW winds at 10 knots at

Point #3.