Tuesday Nov. 7, 2017

Janis Joplin "Kozmic Blues"

(4:23), "Little

Girl Blue" (3:51), Bob Dylan "Like a

Rolling Stone" (5:56), "Knockin' On

Heaven's Door" (3:25), "Thunder on

the Mountain" (4:00), Roy Orbison (with Bruce

Springsteen, Elvis Costello, James Burton, Glen D. Hardin, Tom

Waits, kd lang, Jackson Browne, Bonnie Raitt, JD Souther, T Bone

Burnett, Steven Soles, and Jennifer Warnes) "Oh, Pretty

Woman" (6:18)

We'll finish up the ice crystal

process today and look at some of the varieties of types of

precipitation that can fall to the ground. That probably

won't take the whole class period so we'll get started on some

different material near the end of the class.

Snow Crystals

Now we will see what can happen once the ice crystal has had a

chance to grow a little bit.

Once an ice crystal has grown a little bit it becomes a snow

crystal (this figure is on p. 102 in the ClassNotes). Snow

crystals can have a variety of shapes (plates, dendrites,

columns, needles, etc.; these are called crystal habits)

depending on the conditions (temperature and moisture) in the

cloud. Dendrites are the most common because they form

where there is the most moisture available for growth.

With more raw material available it makes sense there would be

more of this particular snow crystal shape.

Here

are some actual photographs of snow crystals (taken with a

microscope). Snow crystals are usually 100

or a few 100s of micrometers in diameter (tenths of a

millimeter in diameter). That's visible but you'd need

a microscope to see the detail shown above.

You'll find some much better photographs and a pile of

additional information about snow crystals at www.snowcrystals.com.

Here's another

source of some pretty amazing photographs.

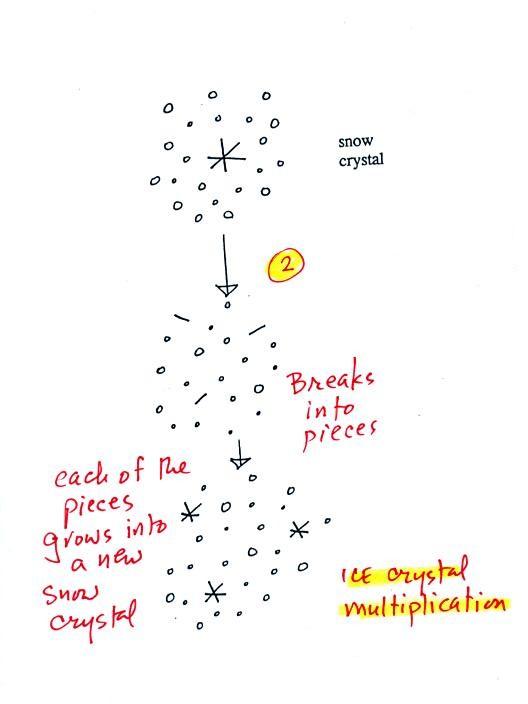

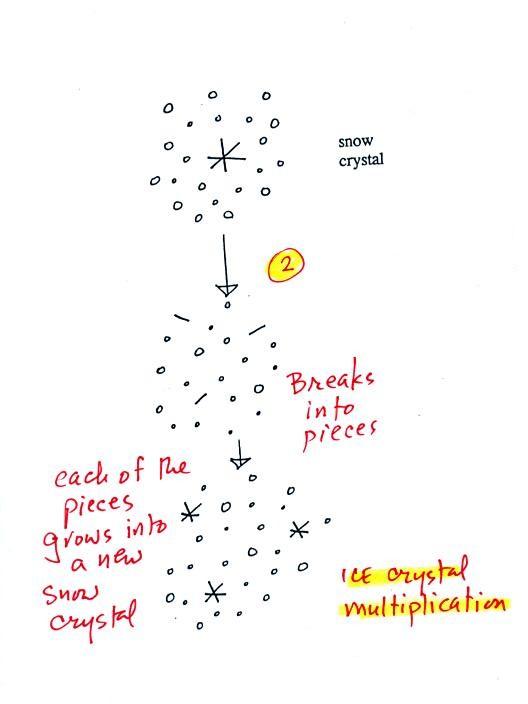

A variety of things can happen once

a snow crystal forms.

First it can break into pieces, then

each of the pieces can grow into a new snow crystal.

Because snow crystals are otherwise in rather short supply,

ice crystal multiplication is a way of increasing the amount

of precipitation that ultimately falls from the cloud.

Snowflakes

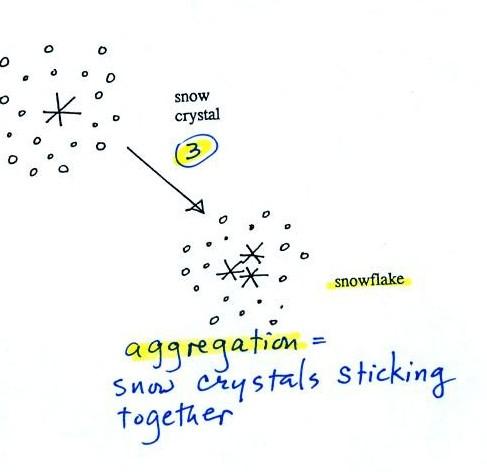

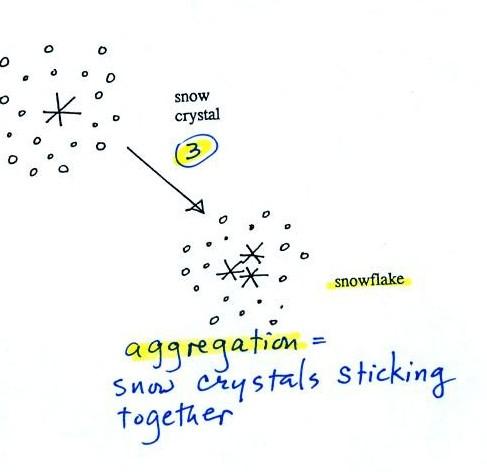

Several snow crystals can collide and

stick together to form a snowflake. Snow crystals are

small, a few tenths of a millimeter across. Snowflakes

can be much larger and are made up of many snow crystals stuck

together. The sticking together or clumping together of

snow crystals is called aggregation (I frequently forget the

name of this process and don't expect you to remember it

either).

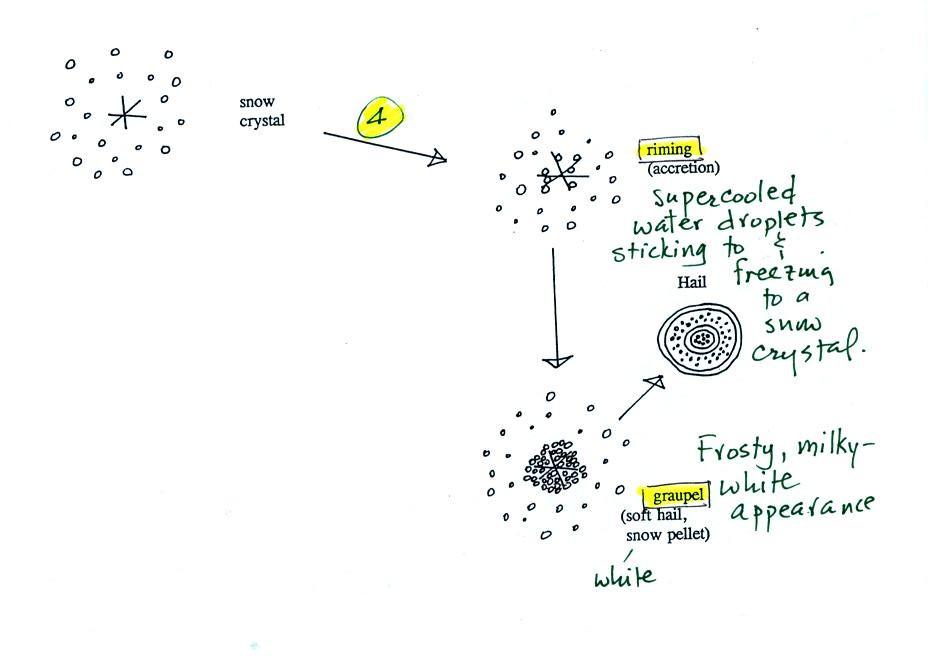

Riming (accretion) and graupel

(aka snow pellets & soft hail)

The next process and particle are something that I hope you

will remember.

Snow crystals can collide with

supercooled water droplets. The water droplets may stick

and freeze to the snow crystal. This process is called

riming or accretion (note this isn't called collision

coalescence even though it is the same idea). If a snow

crystal collides with enough water droplets it can be

completely covered with ice. The resulting particle is

called graupel. Graupel is sometimes mistaken for hail

and is called soft hail or snow pellets. Rime ice has a

frosty milky white appearance. A graupel particle

resembles a miniature snow ball. Or smaller finer

grained version of the shaved ice in a "snow cone."

Graupel particles often serve as the nucleus for a

hailstone. You'll find lots of pictures

on the internet (also several slides explaining the

difference between hail, graupel, and sleet).

Graupel is made of milky white

frosty rime ice. Sleet, we will find, is made of clear

ice. Here are some pictures to help you better appreciate

the differences in appearance.

Here's a snowball. It's white

and you can't see through it. It's made up of lots

of smaller crystals of ice. Graupel is just a

small snowball.

source

|

The ice in a snow cone is basically

the same. Lots of smaller chunks of ice.

The ice is frosty white (before you added the flavored

syrup).

source

|

Graupel vs sleet, rime ice

vs clear ice

Graupel is sometimes referred as snow pellets. Sleet is

sometimes called ice pellets.

clear transparent sugar crystals

source of

this photograph

|

frosty white sugar cubes

are made up of many much smaller grains of sugar

|

Appreciating the differences in the appearance of clear ice and

rime ice.

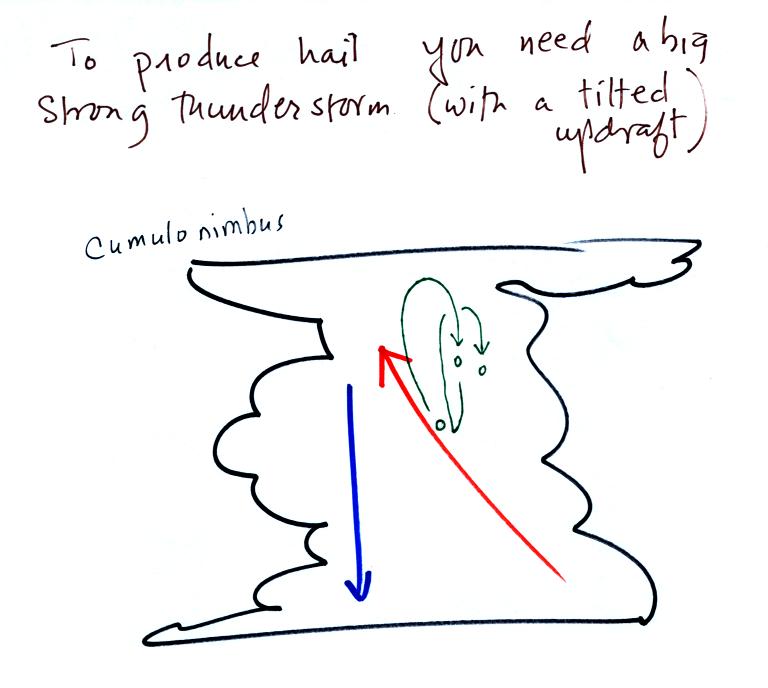

Formation of hail

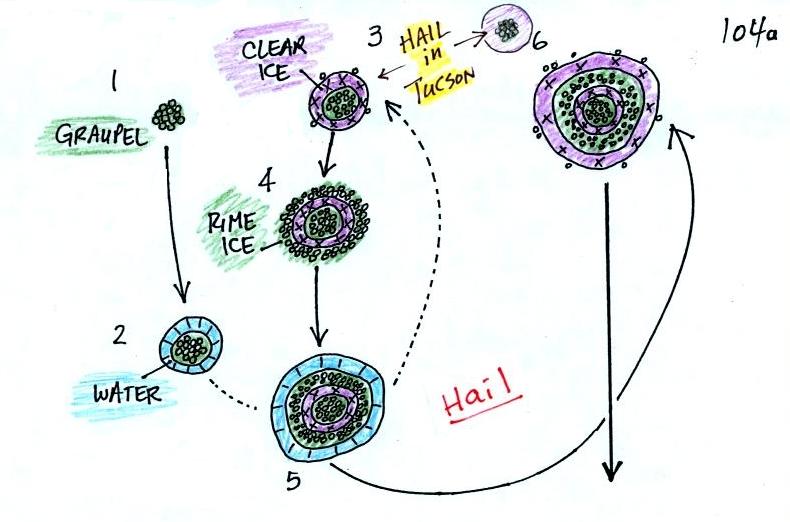

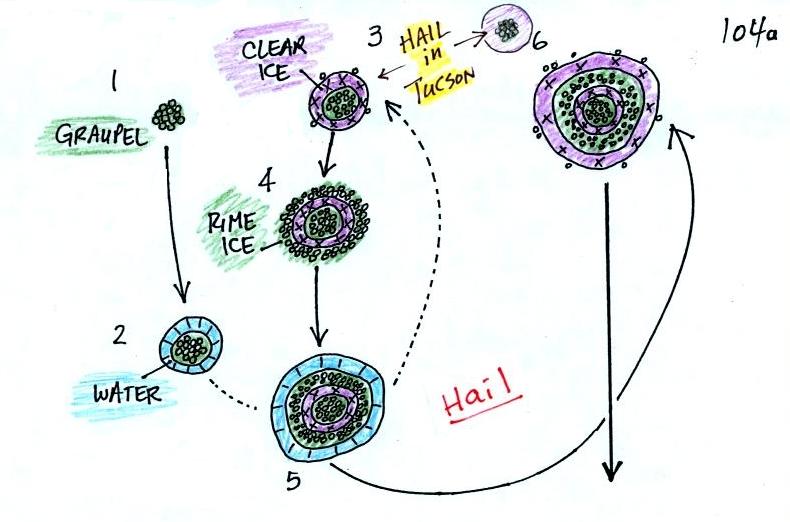

This figure gives you an idea of

how hail forms.

In

the figure above a hailstone starts with a graupel particle

(Pt. 1, colored green to represent rime ice). The

graupel falls or gets carried into a part of the cloud where

it collides with a large number of supercooled water droplets

which stick to the graupel but don't immediately freeze.

The graupel gets coated with a layer of water (blue) at Pt.

2. The particle then moves into a colder part of the

cloud and the water layer freeze producing a layer of clear

ice (the clear ice, colored violet, has a distinctly different

appearance from the milky white rime ice), Pt. 3. In Tucson this is often the only example of hail

that you will see: a graupel particle core with a single layer

of clear ice.

Hail that falls to the ground in Tucson usually just has a

graupel core and a single layer of clear ice. In the

severe thunderstorms in the Central Plains, the hailstone can

pick up additional layers of rime ice and clear ice and

hailstones can be composed

of many alternating layers of rime and clear ice. An

unusually large hailstone (around 3 inches in diameter) has been

cut in half to show (below) the different layers of ice.

The picture below is close to actual size. If something

like this were to hit you in the head it would split your skull

open. Here's some pretty good video of a hailstorm in

Phoenix.

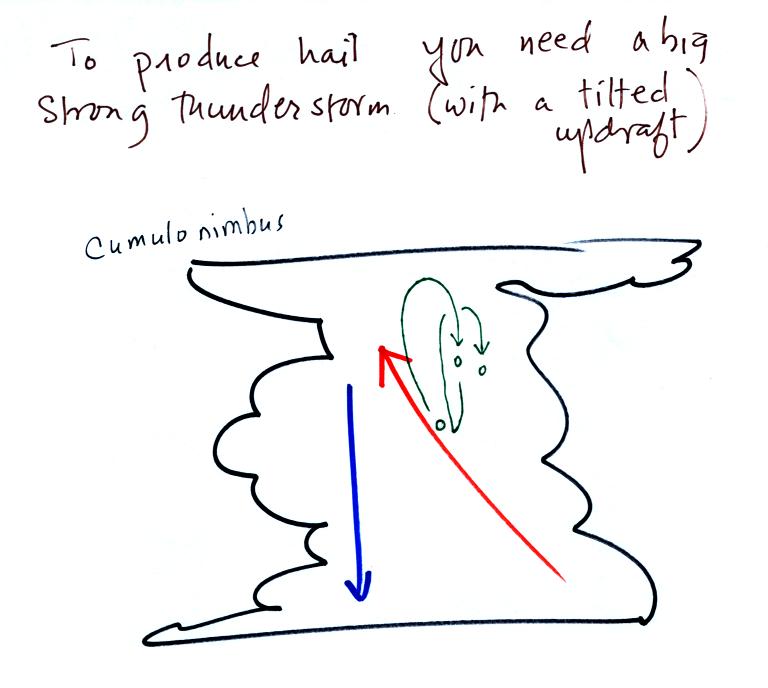

Hail is produced in strong thunderstorms

with tilted updrafts. You would never see hail (or

graupel) falling from a nimbostratus cloud. Here

is a photo of a record setting 8" diameter hailstone

collected in South Dakota. It is currently the national

record holder. Here's

another hailstone that is almost as big. It holds

the record for Oklahoma. Click here

to see a gallery of images showing hail damage to automobiles.

The growing hailstone can fall back into

the updraft (rather than falling out of the cloud) and be

carried back up toward the top of the cloud. In this way

the hailstone can complete several cycles through the interior

of the cloud. The article above mentions a supercell

thunderstorm. We will discuss these later in the semester.

Types of precipitation

Finally on p. 103 in the

ClassNotes are illustrations of some of the things that can

happen once a precipitation particle falls from a cloud.

I've split this into two groups for clarity.

Essentially all the rain that

falls in Tucson is produced by the ice crystal process.

The left figure above shows how this happens. A falling

graupel particle or a snow flake moves into warmer air and

melts. The resulting drops of water fall the rest of the

way to the ground and would be called RAIN.

In the middle picture graupel particles can survive the trip

to the ground without melting even in the summer. Many

people on the ground would call this hail but that wouldn't be

quite right. Graupel is less common in the winter because

it comes from thunderstorms and they don't form very often in

the winter. Snow can survive the trip to the ground in the

winter but not the summer. Snow does occasionally make it

to the valley floor in Tucson.

Sometimes the falling raindrops will evaporate before reaching

the ground. This is called VIRGA and is pretty

common early in the summer thunderstorm season in Arizona when

the air is still pretty dry. Lightning that comes from

thunderstorms that aren't producing much precipitation is called

"dry lightning" and often starts brush fires.

Rain will sometimes freeze before reaching the ground.

The resulting particle of clear ice is called SLEET.

FREEZING RAIN by contrast only freezes once it reaches the

ground. Everything on the ground can get coated with a thick

layer of ice. It

is nearly impossible to drive during one of these "ice

storms." Sometimes the coating of ice is heavy enough

that branches on trees are broken and power lines are brought

down (either by the weight of ice or falling tree limbs).

It sometimes takes several days for power to be

restored. Here's a gallery

of images taken after ice storms.

This is the end of the material that will

be covered on this week's quiz.

How and why surface and upper level winds blow the

way they do.

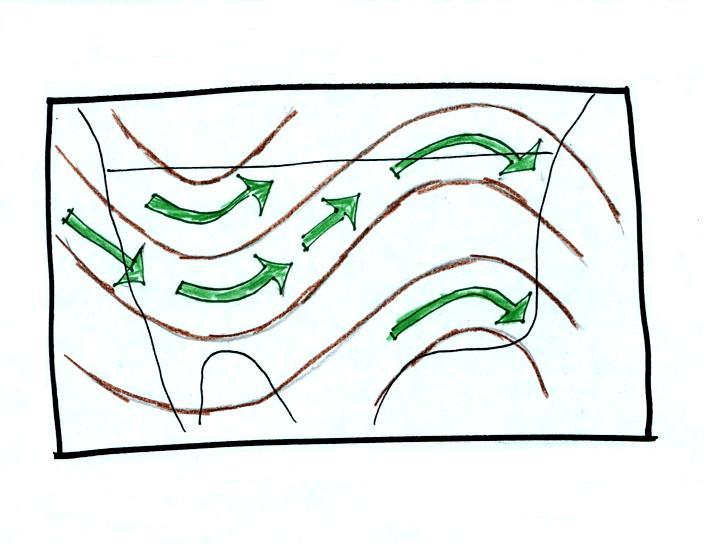

Some real world examples are shown in the figure below (found

on p. 121 in the ClassNotes). The two largest types of

storm systems, middle latitude storms (extratropical cyclones)

and hurricanes (tropical cyclones), develop around surface

centers of low pressure

the term

cyclone refers to winds blowing around a center of low

pressure

Earlier in the semester we learned that winds spin

counterclockwise around centers of low pressure in the northern

hemisphere. Tuesday next week is the day we start to worry

about what happens in the southern hemisphere. Winds

change direction and spin clockwise around low pressure in the

southern hemisphere.

Winds spin clockwise around "anticyclones" (high pressure) in

the northern hemisphere and counterclockwise around highs in the

southern hemisphere.

Why do winds blow in opposite directions around

high and low pressure. Why do they even spin at

all.

Why do the winds change directions when you move from the

northern to the southern hemisphere.

These are the kinds of questions we'll be addressing next

week. And it's not just the wind. Ocean

currents off the East and West Coasts of the US spin in a

clockwise direction. They reverse direction and spin

counterclockwise off the east and west coasts of South America.

Something else to notice in the figure. Storm

systems in the tropics (0 to 30 degrees latitude) generally

move from east to west in both hemispheres, in both

hemispheres. At middle latitudes (30 to 60 degrees),

storms move in the other direction, from west to east.

That's not something we will cover in class, rather it will

be the subject on an upcoming Optional Assignment.

We'll be able to learn most of what we need to know about

surface and upper level winds in 10 relatively easy steps

(though I've broken several of the steps into smaller parts)

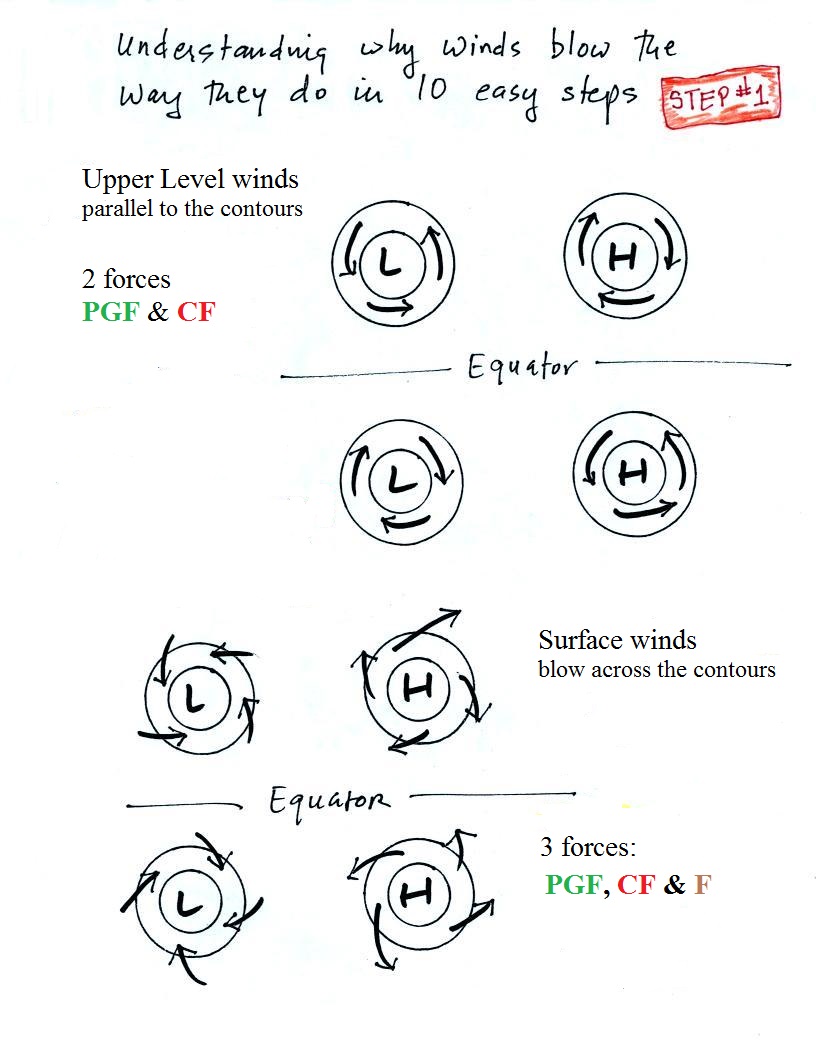

Step #1 - Upper level and surface winds in the N. and

S. hemisphere - summary

The next figure is on p. 122a in the ClassNotes.

Upper level winds spinning around high and low pressure in

the northern and southern hemispheres are shown in the first set

of four pictures. All the possibilities are here.

The first thing to notice is that upper level winds blow

parallel to the contours. Just 2 forces, the

pressure gradient force (PGF)

and the Coriolis force (CF),

cause the winds to blow this way. Eventually you will be

able to draw the directions of the forces for each of the four

upper level winds examples. Here is an upper level

wind example showing what you will be able to do.

The four drawings at the bottom of the page show surface winds

blowing around high and low pressure in the southern

hemisphere. Surface winds blow across the contour

lines slightly, always toward low pressure.

A third force, the frictional force is what causes this to

occur. He is an example of what

you will be able to say about surface winds.

Upper Level Charts Pt. 1 - Basic Features

We covered surface weather maps earlier in the semester

but not upper-level charts. So we'd better learn some of

the basics now. Also there is an Optional

Assignment that accompanies some suggested reading on

Upper Level Charts. The reading is split into

three parts, we'll only look at the first part in class.

Upper level is just referring to atmospheric conditions at some

level above the ground (weather maps are actually drawn showing

conditions at multiple altitude above the ground. Upper

level conditions can affect the development and movement of

surface features (and vice versa).

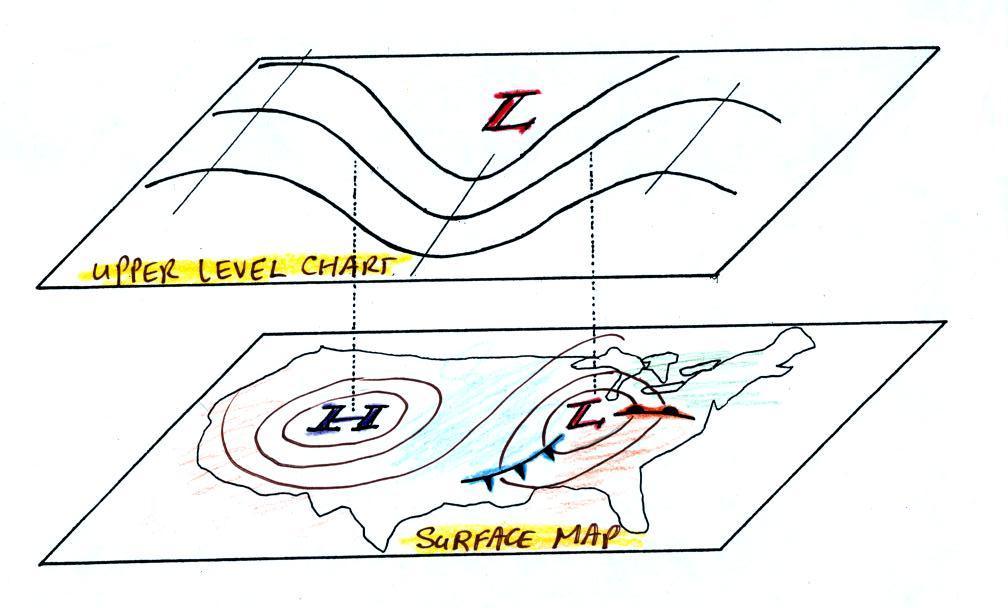

In this first section

we'll just learn 3 basic facts about upper level

charts. First the overall appearance is somewhat

different from a surface weather map. The pattern on a

surface map can be complex and you generally find circular

(more or less) centers of high and low pressure (see the

bottom portion of the figure below). You can also find

closed high and low pressure centers at upper levels, but

mostly you find a relatively simple wavy pattern like is

shown on the upper portion of the figure below (sort of a

3-dimensional view)

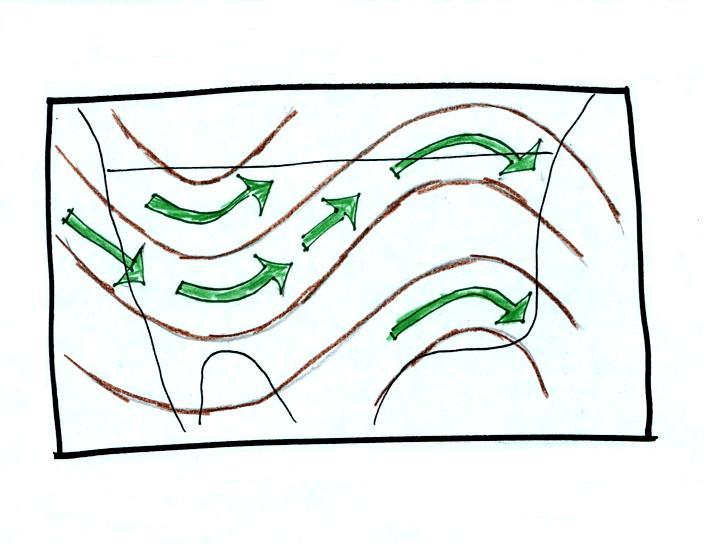

A simple upper

level chart pattern is sketched below (a map view).

There are two basic features: wavy lines that dip southward

and have a "u-shape"

and lines that bend northward and have an "n-shape".

The u-shaped portion

of the pattern is called a trough. The n-shaped portion is

called a ridge.

Troughs are produced by large volumes of cool or

cold air (the cold air is found between the ground and the

upper level that the map depicts). The western half of

the country in the map above would probably be experiencing

colder than average temperatures. Large volumes of

warm or hot air produce ridges. We'll see why this is

true in "Upper level charts pt. 2".

An

actual example of an upper level map is shown below at

left. Temperature data is shown in the figure

at right. Colder than normal temperatures at right

match up well with an upper level trough on the map at

left. The warmer than average temperatures along the

western US are associated with the eastern edge of an

upper level ridge. Tucson is expecting near record

high temperatures this afternoon.

|

|

A simple upper level

pattern from February 10, 2016. The eastern

half of the United States was under an upper level

trough. There is a ridge over the western half

of the country. (source

of this image)

|

This is a "temperature

departure from normal" map. The blue that

covers much of the eastern part of the country

indicates colder than normal. Orange and red

mean warmer than normal temperatures. (source

of this chart) |

The winds on upper level charts blow parallel

to the contour lines generally from west to east. This

is a little different from surface winds which blow across the

isobars toward low pressure. An example of surface winds

is shown below.

That's it for the in-class coverage of upper level

charts. Really all you need to be able to do is

1. identify troughs and ridges,

2. remember that troughs are associated with cold air &

ridges with warm air, and

3. remember that upper level winds blow parallel to the contour

lines from west to east.