Wednesday Mar. 27, 2013

click here to download today's notes

in a more printer friendly format

"Tres Ninas" from local guitarist Domingo DeGrazia (son

of artist Ted DeGrazia).

You can listen to short segments of some of his songs here.

Pt. 1 and Pt. 2 of the Quiz #3 Study Guide

are now available online. Quiz #3 is Wednesday next week

(Apr. 3). There will be reviews Mon. and Tue. afternoon from

4 - 5 pm in Haury (Anthropology) 129.

The Humidity

Problems Optional Assignment that was turned in on Monday

has been graded and was returned today. A detailed set of answers to

the questions with some explanation of how to solve the

problems is now available.

Finally 3 new 1S1P report

topics are now available online. They all have

different due dates. There is no limit on the number of

reports you can write on these new topics.

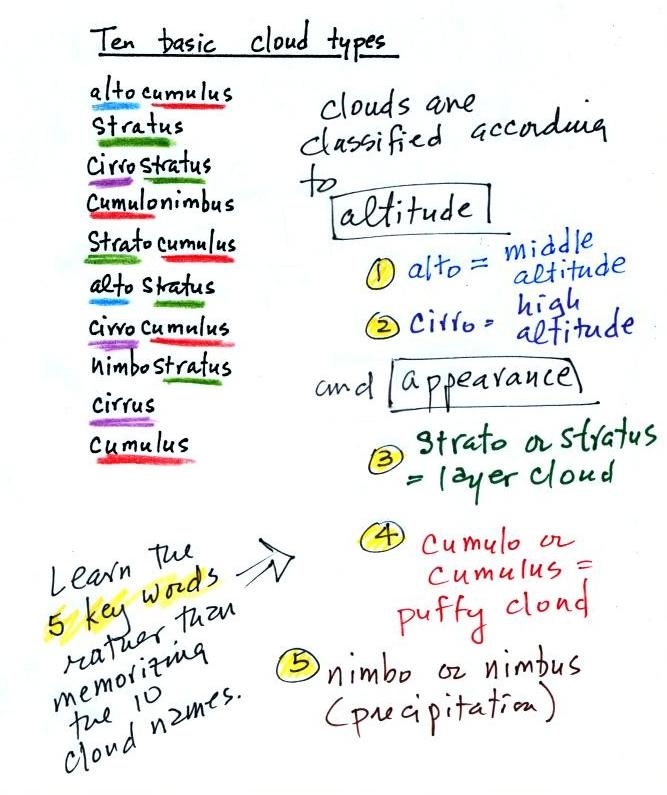

Today's class was devoted entirely to learning how to

identify and name clouds. The ten main cloud types are

listed below (you'll find this list on p. 95 in the ClassNotes).

I'm hoping you'll try to learn these 10

cloud names. There is a smart and a not-so-smart way of

learning these names. The not-so-smart way is to just

memorize them. Because they all sound alike you will

inevitably get them mixed up. A better way is to

recognize that all the cloud names are made up of key

words. The 5 key words tell you something about the

cloud's altitude and appearance. My recommendation is to

learn the key words.

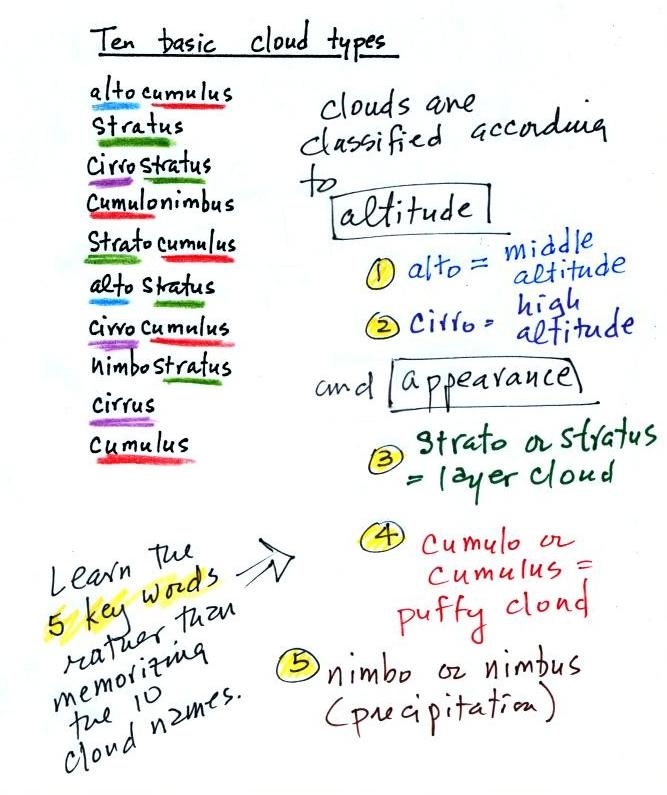

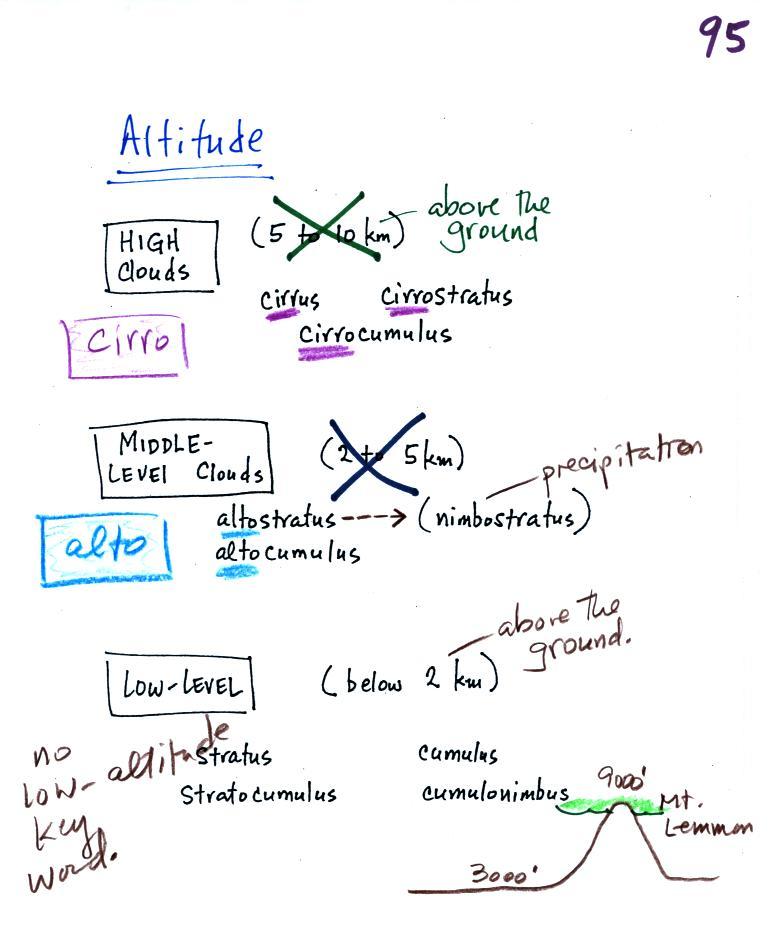

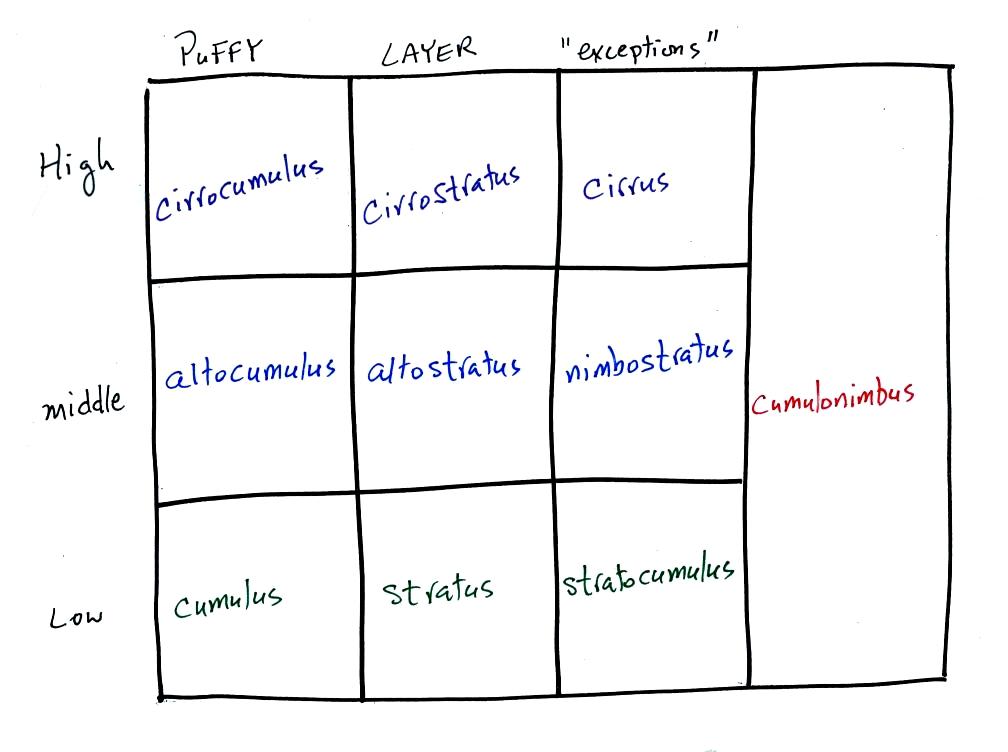

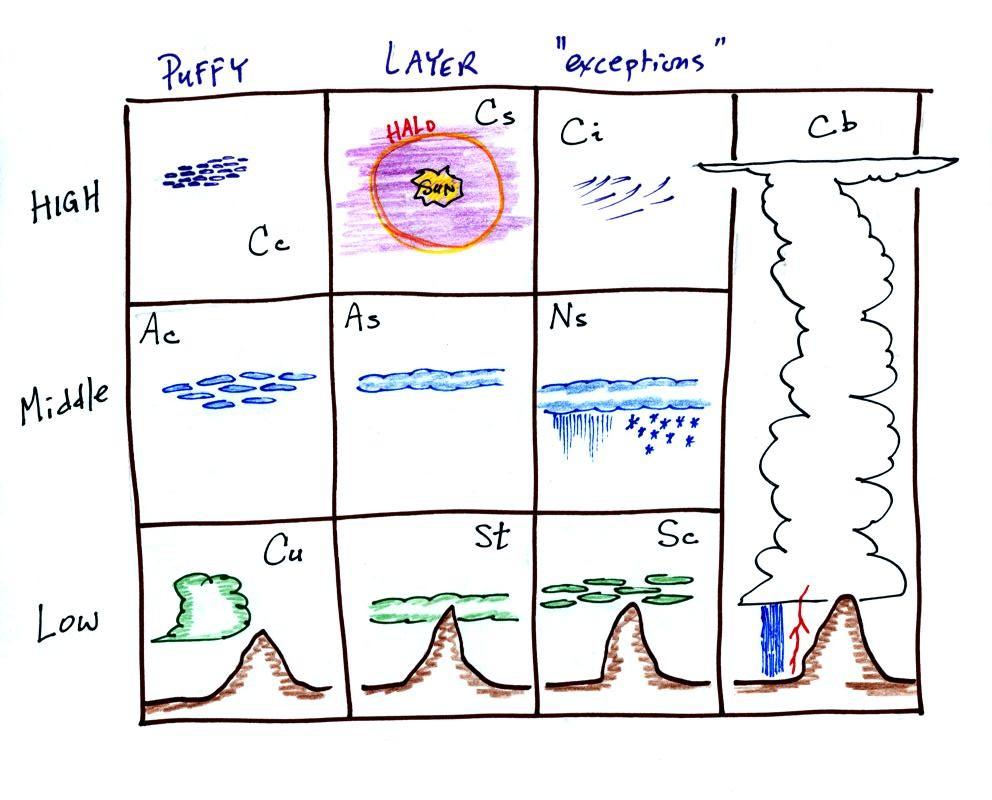

Drawing a chart like this on a blank sheet of paper is a good

way to review cloud identification and classification.

There are 10 boxes in this chart,

one for each of the 10 main cloud types. Eventually, you

should be able to put a cloud name, a sketch, and a short

written description in each square.

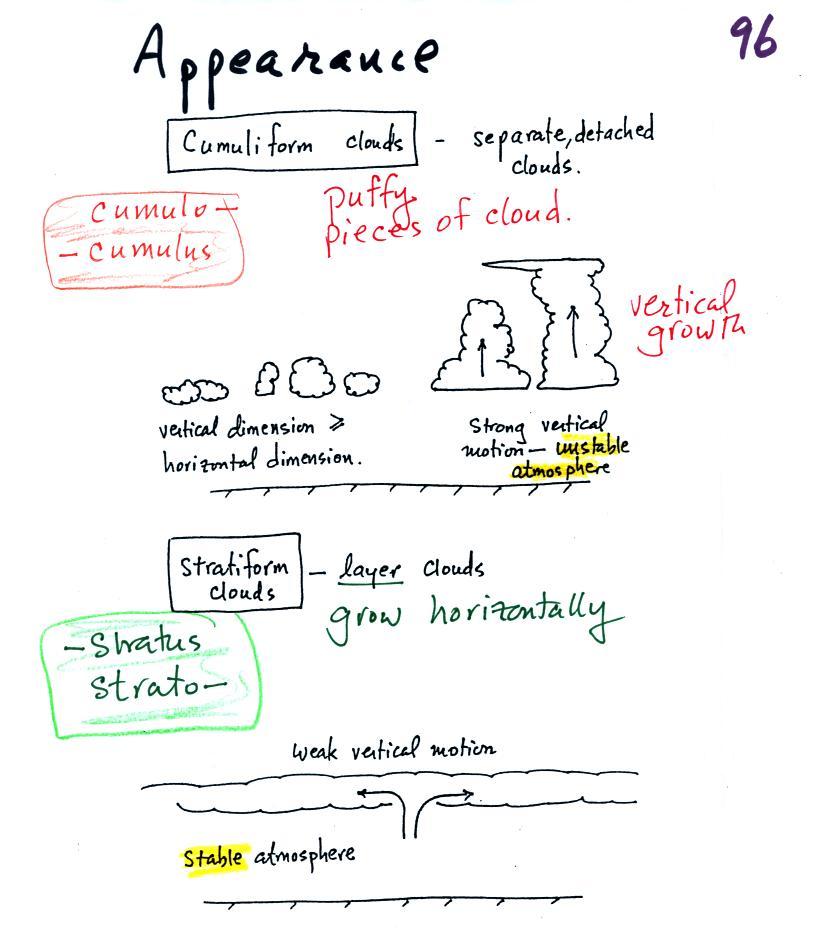

Clouds are classified according to the

altitude at which they form and the appearance of the

cloud. There are two key words for altitude and two key

words for appearance.

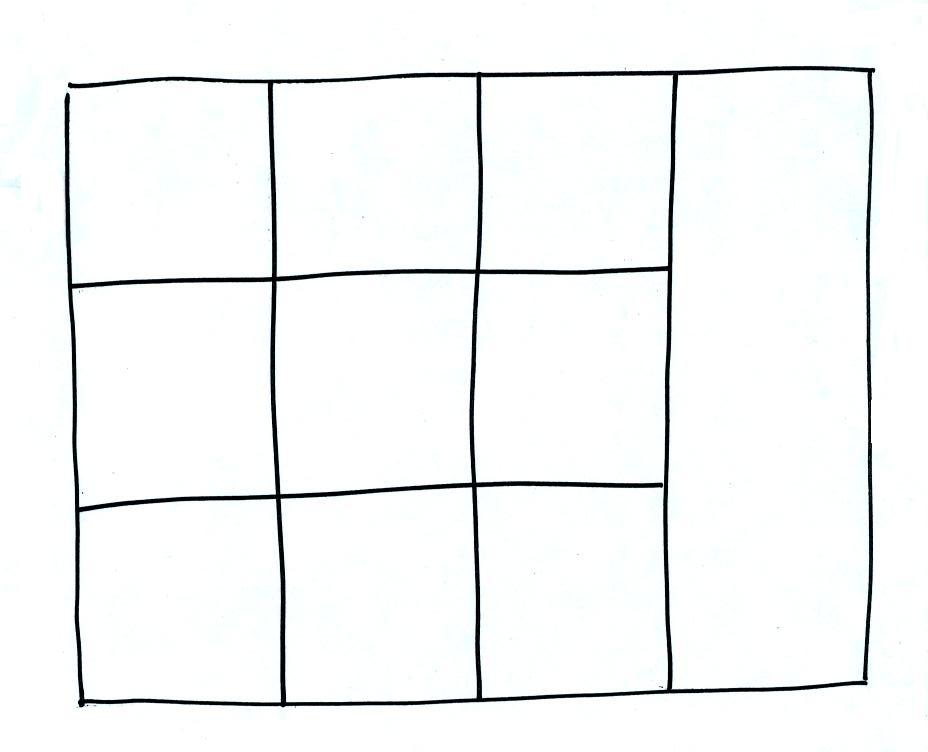

Clouds are grouped into one of three

altitude categories: high, middle level, and low. It is very hard to just look up in the

sky and determine a cloud's altitude. You will need to

look for other clues to distinguish

between high and middle altitude clouds. We'll learn

about some of the clues when we look at cloud pictures later

in the class.

Cirrus or cirro

identifies a high altitude cloud. There are three types

of clouds found in the high altitude category..

Alto in a cloud name means the cloud is found at middle

altitude. The arrow connecting altostratus and

nimbostratus indicates that they are basically the same kind

of cloud. When an altostratus cloud begins to produce

rain or snow its name is changed to nimbostratus. A

nimbostratus cloud may become somewhat thicker and lower than

an altostratus cloud. Sometimes it might sneak into the

low altitude category.

There is no key word for low altitude clouds. Low

altitude clouds have bases that form 2 km or less above the

ground. The summit of Mt. Lemmon in the Santa Catalina mountains

north of Tucson is about 2 km above the valley

floor. Low altitude clouds will

have bases that form at or below the summit of Mt. Lemmon.

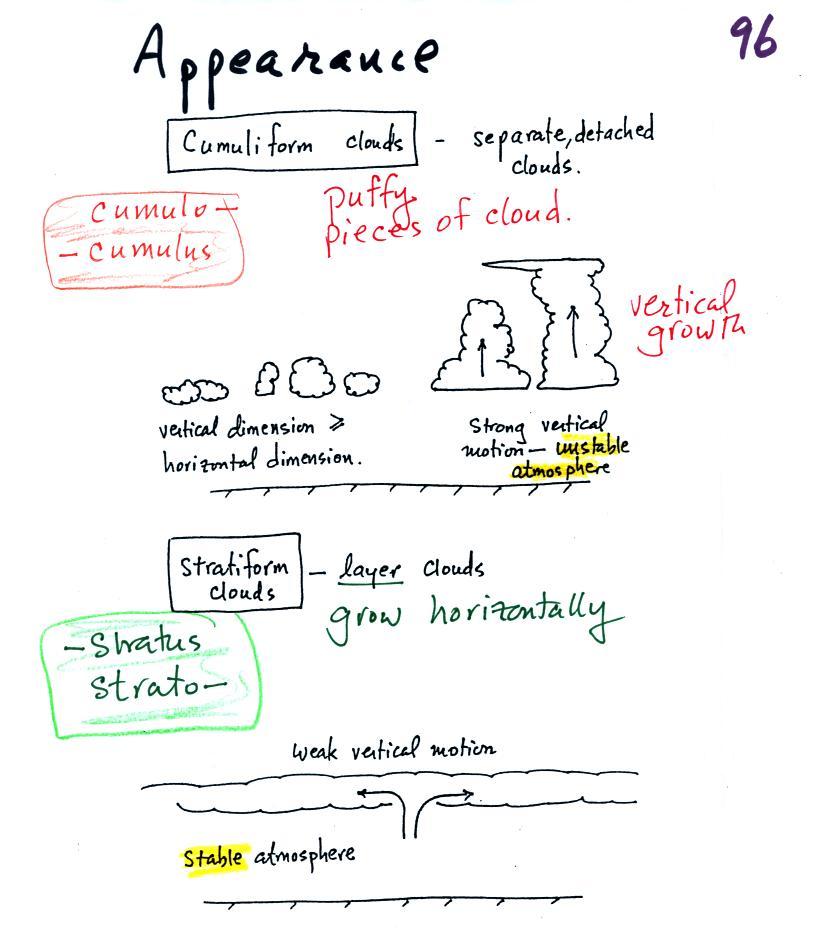

Clouds can have a patchy of puffy (or

lumpy, wavy, splotchy or ripply) appearance. These are

cumuliform clouds and will have cumulo

or cumulus in their name. In an unstable atmosphere

cumuliform clouds will grow vertically. Strong

thunderstorms can produce dangerous severe weather.

Stratiform clouds grow

horizontally and form layers. They form when the

atmosphere is stable.

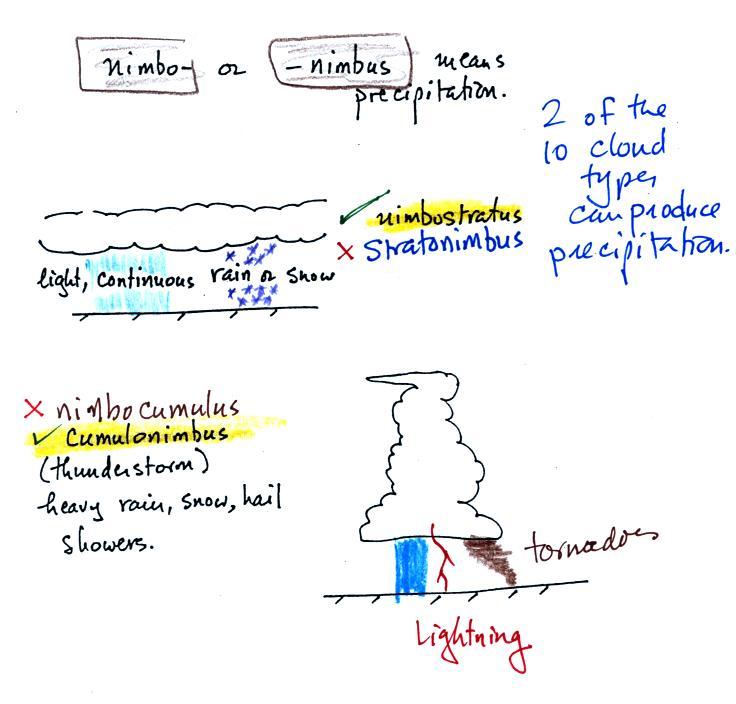

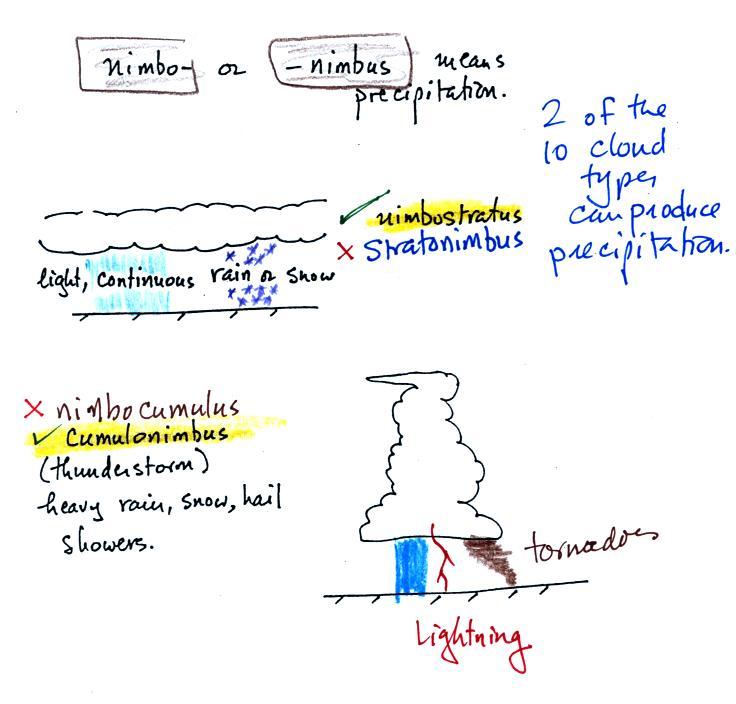

The last key word, nimbo

or nimbus, means precipitation (it is also the name of a local brewing company).

Only two of the 10 cloud types are able to produce

(significant amounts of) precipitation. It's not as easy

as you might think to make precipitation. We'll start to

look at precipitation producing processes in class starting on

Friday.

Nimbostratus clouds tend to produce

fairly light precipitation over a large area. Cumulonimbus

clouds produce heavy showers over localized areas.

Thunderstorm clouds can also produce hail, lightning, and

tornadoes. Hail would never fall from a

Ns cloud.

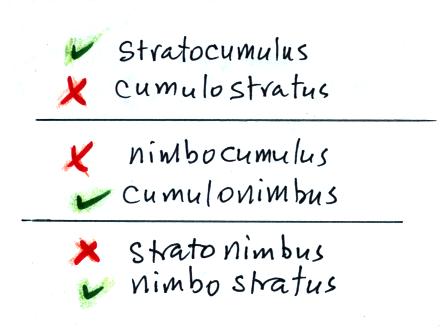

While you are still learning the cloud names you might put the

correct key words together in the wrong order (stratonimbus instead of nimbostratus,

for example). You won't be penalized for those kinds of

errors in this class because you are putting together the right

two key words.

Here's the cloud chart from earlier.

We've added the three altitude categories along the vertical

side of the figure and the two appearance categories along the

top. By the end of the class we will add a picture to each

of the boxes.

On Monday we cooled some moist air and created a cloud in a

bottle. We were able to make the cloud more visible by

adding smoke from a burning match to the demonstration. The

smoke particles acted as condensation nuclei.

Here's Mother Nature's version of the cloud in a bottle

demonstration. A brush fire in this picture is heating up

air and causing it to rise. Combustion also adds some

moisture and lots of smoke particles to the air. You can see

that initially the rising air doesn't form a cloud. A little

higher and once the rising air has cooled enough (to the dew

point) a cloud does form. And notice the cloud's appearance

- puffy and not a layer cloud. Cumulo or cumulus should be

in the cloud name. These kinds of fire caused clouds are

called pyrocumulus clouds. The example above is from a

Wikipedia article about these kinds of clouds.

The

fire in this case was the "Station Fire" burning near Los

Angeles in August 2009.

Next we looked at photographs of

most of the 10 cloud types. You'll find the written descriptions of

the cloud types in the images below on pps

97-98 in the ClassNotes.

HIGH ALTITUDE CLOUDS

High altitude

clouds are thin because the air at high altitudes is very

cold and cold air can't contain much moisture, the raw

material needed to make clouds (the saturation mixing

ratio for cold air is very small). These clouds are

also often blown around by fast high altitude winds.

Filamentary means "stringy" or "streaky". If you

imagine trying to paint a Ci

cloud you might dip a small pointed brush in white paint

brush it quickly and lightly across a blue colored

canvas. Here are some pretty good photographs of

cirrus clouds (they are all from a Wikipedia

article on Cirrus Clouds)

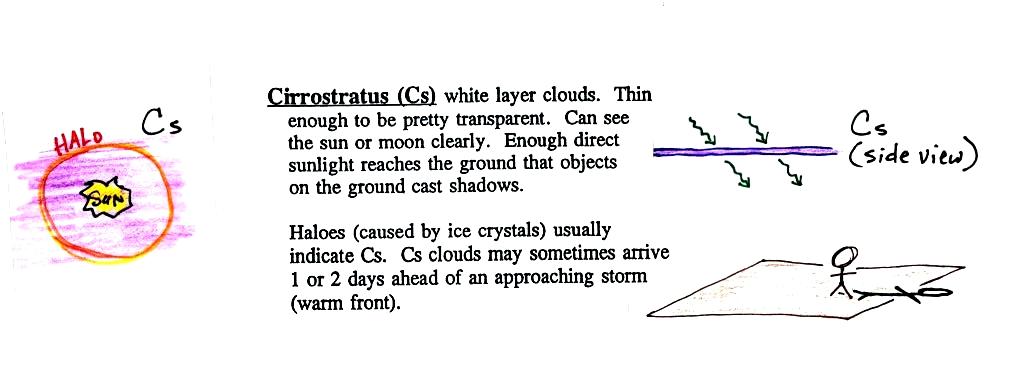

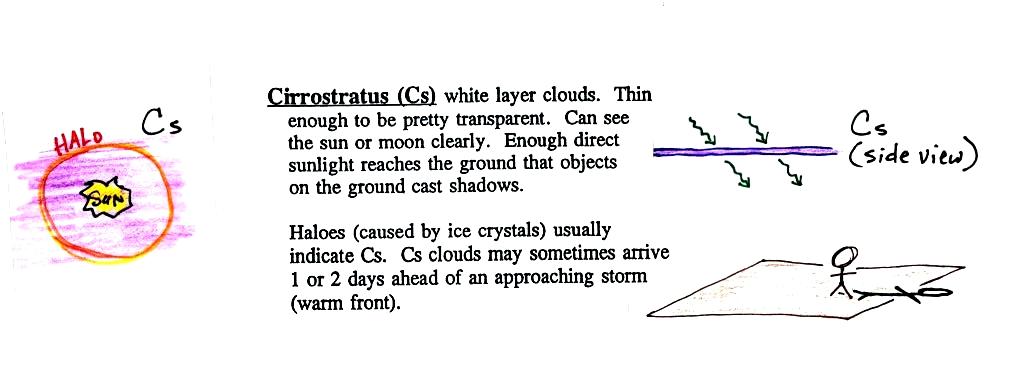

A cirrostratus

cloud is a thin uniform white layer cloud (not purple as shown

in the figure) covering part or all of the sky. They're

so thin you can sometimes see blue sky through the cloud

layer. Haloes are a pretty sure indication that a

cirrostratus cloud is overhead. If you were painting Cs

clouds you could dip a broad brush in watered down white paint

and then paint back and forth across the canvas.

Now a detour to briefly discuss

haloes and sundogs.

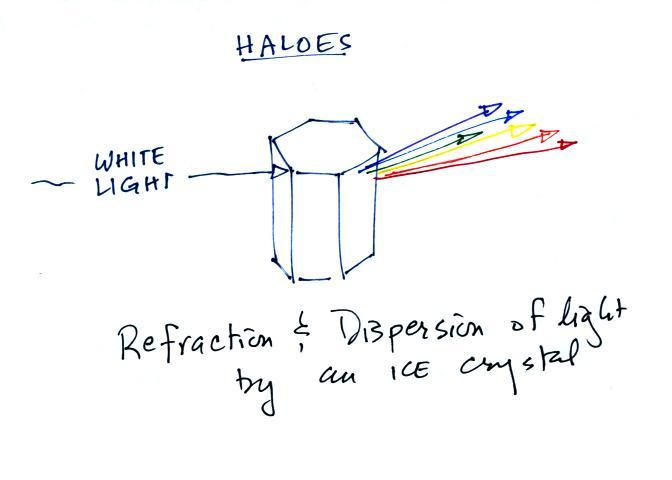

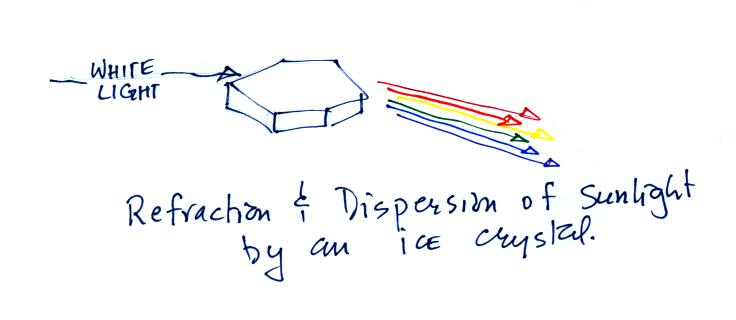

Haloes are produced when white light (sunlight or

moonlight) enters a 6 sided ice crystal. The light is

refracted (bent). The amount of bending depends on the

color (wavelength) of the light (dispersion). The

white light is split into colors just as light passing

through a glass prism. Crystals like this (called

columns) tend to be randomly oriented in the air. That

is why a halo forms a complete ring around the sun or

moon. You don't usually see all the colors, usually

just a hint of red or orange on the inner edge of the halo.

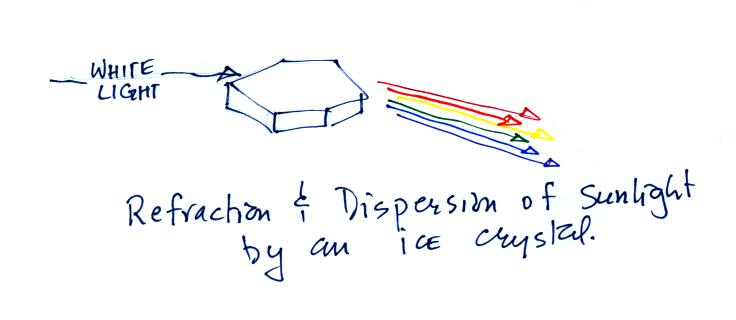

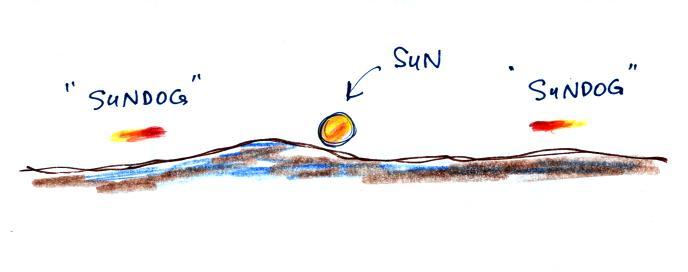

This is a flatter crystal and is

called a plate. These crystals tend to all be horizontally

oriented and produce sundogs which are only a couple of small

sections of a complete halo. A sketch of a sundog is shown

below.

Sundogs

are pretty common and are the patches of light seen to the right

and left of the rising or setting sun.

A very bright halo is shown at upper

left with the sun partially blocked by a building (the cloud

is very thin and most of the sunlight is able to shine

straight through). Note the sky inside the halo is

darker than the sky outside the halo. The halo at upper

right is more typical of what you might see in Tucson.

Thin cirrus clouds may appear thicker at sunrise or sunset

because the sun is shining through the cloud at a steeper

angle. Very bright sundogs (also known as parhelia) are

shown in the photograph at bottom left. The sun in the

photograph at right is behind the person. You can see

both a halo and a sundog (the the left of the sun) in this

photograph. Sources of these

photographs: upper

left, upper right,

bottom row.

If you spend enough time outdoors

looking up at the sky you will eventually see all 10 cloud

types. Cirrus and cirrostratus clouds are fairly

common. Cirrocumulus clouds are a little more

unusual. The same is true with animals, some are more

commonly seen in the desert around Tucson (and even in town)

than others.

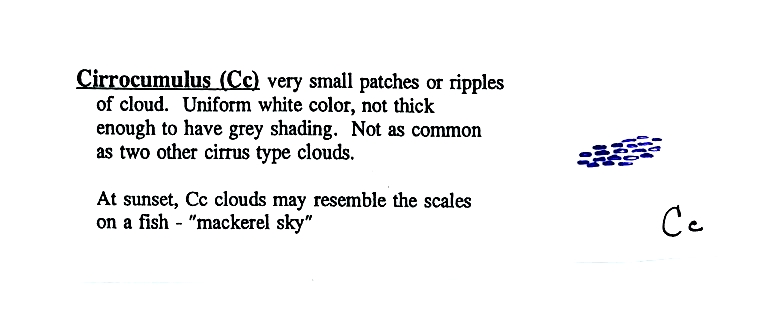

To paint a Cc cloud you

could dip a sponge in white paint and press it gently

against the canvas. You would leave a patchy, splotchy

appearing cloud (sometimes you might see small

ripples). It is the patchy (or wavy) appearance that

makes it a cumuliform cloud.

The table below compares cirrostratus (the cloud on

the left without texture) with a good example of a

cirrocumulus cloud (the "splotchy" appearing cloud on the

right). Both photographs are from the Wikipedia

article mentioned earlier.

MIDDLE ALTITUDE CLOUDS

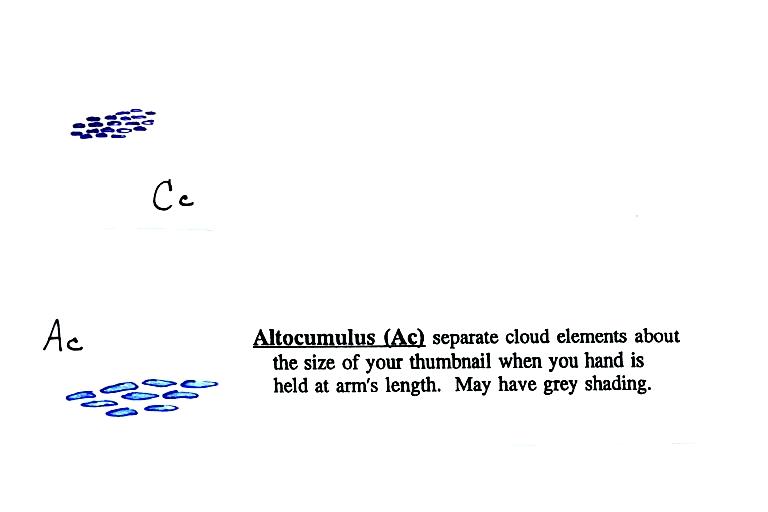

Altocumulus

clouds are pretty common. Note since

it is hard to accurately judge altitude, you must rely on

cloud element size (thumbnail size in the case of Ac) to

determine whether a cloud belongs in the high or middle

altitude category. The cloud elements in Ac

clouds appear larger than in Cc because the cloud is closer to

the ground. A couple of photographs are shown below

(source: Ron Holle for WW2010 Department of

Atmospheric Sciences, the University of Illinois at

Urband-Champaign)

There's a much larger collection in this gallery

of images. The fact that there are so many examples

is an indication of how common this particular type of cloud is.

Altostratus clouds are thick enough that you

probably won't see a shadow if you look down at your

feet. The sun may or may not be visible through the

cloud. Three examples are shown below (the first is

from a

Wikipedia article, the middle and

right photograph are from an Environment

Canada web page)

When (if) an

altostratus cloud begins to produce precipitation, its

name is changed to nimbostratus.

Unless you were there and could see if it was raining or

snowing you might call this an altostratus or even a stratus

cloud. The smaller darker cloud fragments that are below

the main layer cloud are "scud" (stratus fractus) clouds (source

of this image).

LOW ALTITUDE CLOUDS

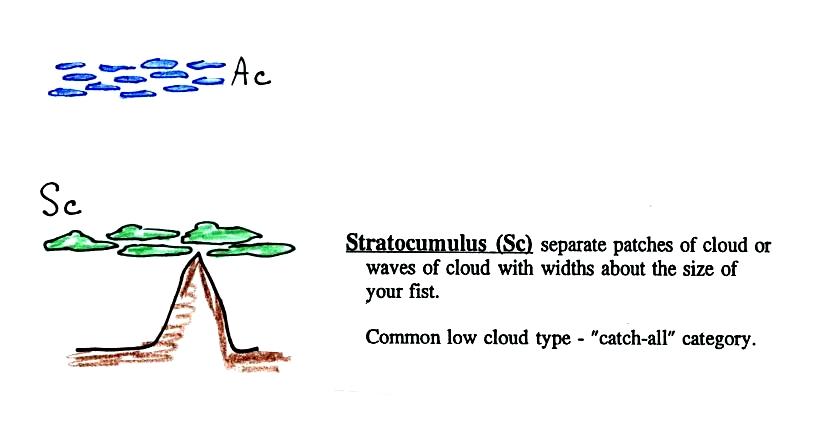

This cloud name is a little

unusual because the two key words for cloud appearance have

been combined, but that's a good description of this cloud

type - a "lumpy layer cloud". Remember there isn't a key

word for low altitude clouds.

Because they are closer to the

ground, the separate patches of Sc are bigger, about fist

size (sources of these images:left

photo, right

photo ).

The patches of Ac, remember, were about thumb nail

size.. If the cloud fragments in the photo at right

are clearly separate from each other (and you would need

to be underneath the clouds so that you could look to make

this determination) these clouds would probably be "fair

weather" cumulus. If the patches of cloud are

touching each other (clearly the case in the left photo)

then stratocumlus would be the correct designation.

I didn't show

any photos of stratus clouds in class. Other than

being closer to the ground they really aren't much

different from altostratus or nimbostratus.

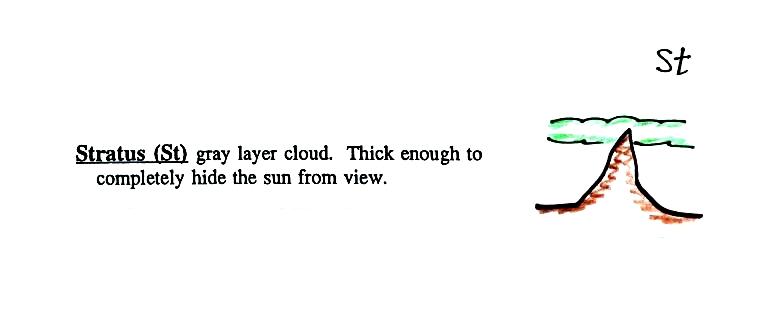

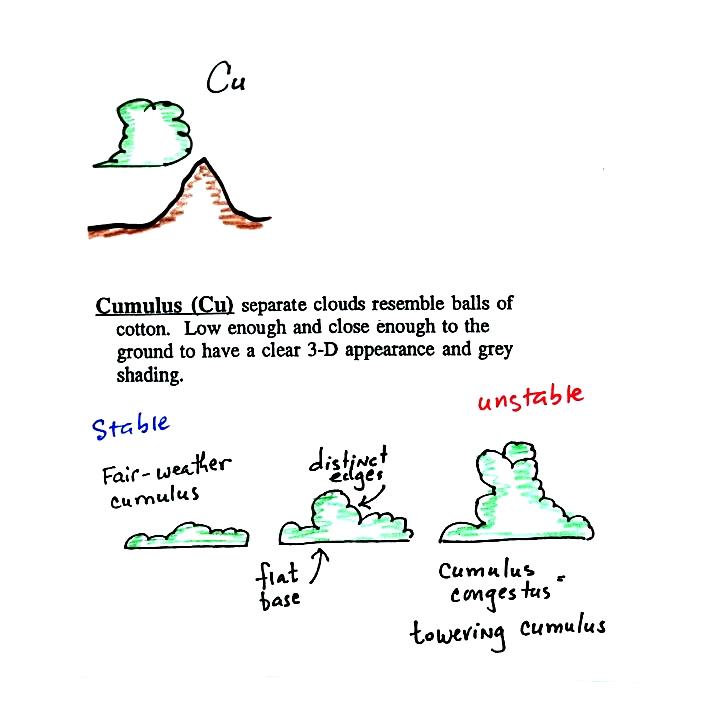

Cumulus

clouds come with different degrees of vertical

development. The fair weather cumulus clouds don't grow

much vertically at all. A cumulus congestus

cloud is an intermediate stage between fair weather cumulus

and a thunderstorm.

A photograph of

"fair weather" cumulus on the left (source)

and cumulus congestus or towering cumulus on the right (source)

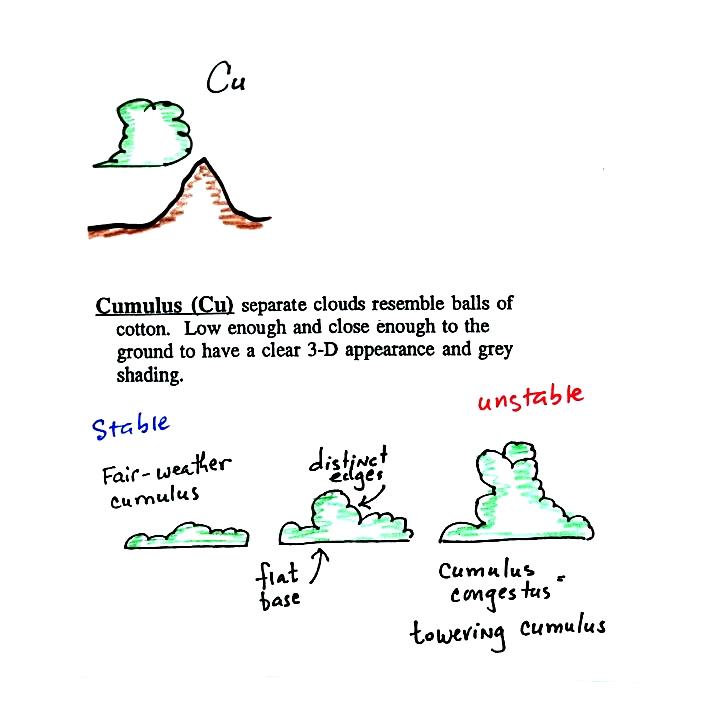

THUNDERSTORMS FIT INTO ALL 3 ALTITUDE CATEGORIES

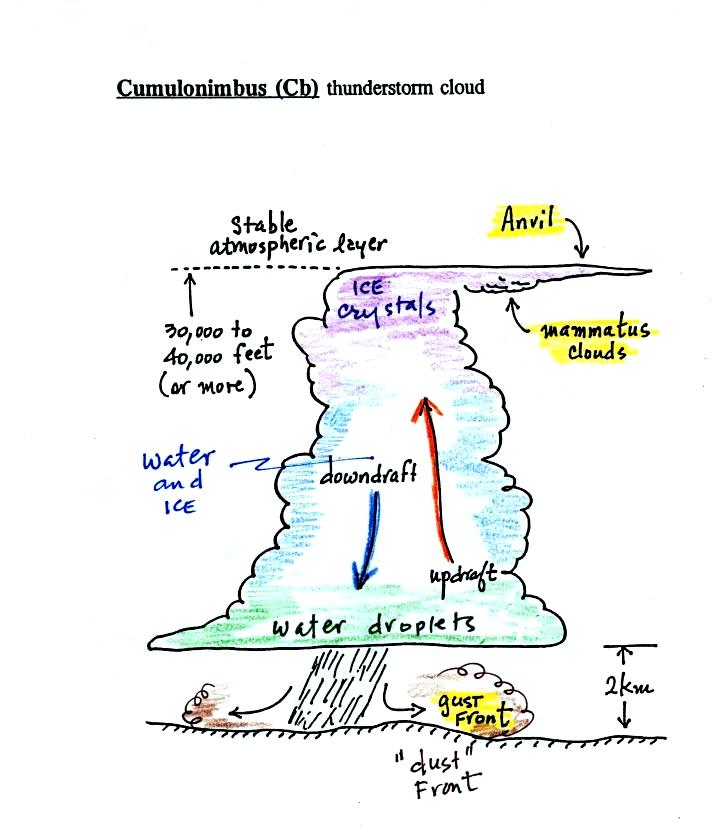

There are lots

of distinctive features on cumulonimbus clouds including the

flat anvil top and the lumpy mammatus

clouds sometimes found on the underside of the anvil.

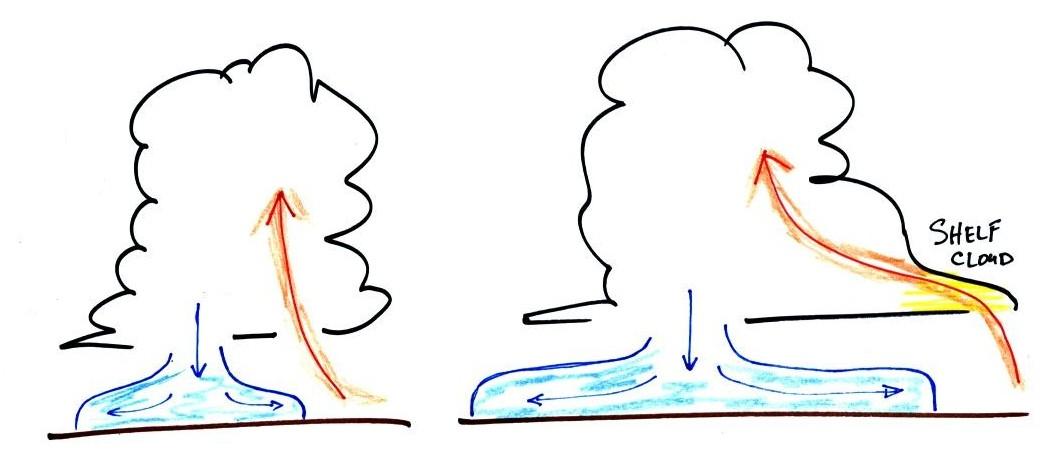

Cold dense

downdraft winds hit the ground below a thunderstorm and spread

out horizontally underneath the cloud. The leading edge

of these winds produces a gust front (in Arizona dust front

might be a little more descriptive). Winds at the ground

below a thunderstorm can exceed 100 MPH, stronger than many

tornadoes.

The top of a thunderstorm (violet

in the sketch) is cold enough that it will be composed of just

ice crystals. The bottom (green) is composed of water

droplets. In the middle of the cloud (blue) both water

droplets and ice crystals exist together at temperatures below

freezing (the water droplets have a hard time freezing).

Water and ice can also be found together in nimbostratus

clouds. We will see that this mixed phase region of the

cloud is important for precipitation formation. It is also

where the electricity that produces lightning is generated.

The top left

photo shows a thunderstorm viewed from space (source: NASA Earth

Observatory). The flat anvil top is the dominant

feature. The remaining three photographs are from the UCAR Digital Image

Library. The bottom left photograph shows heavy by

localized rain falling from a thunderstorm. At bottom

right is a photograph of mammatus clouds found on the

underside of the flat anvil cloud.

We were starting to

run out of time at this point, but I'm including the remainder

of the material on clouds so that it will all be together in

one place.

Cold air spilling out of the base

of a thunderstorm is just beginning to move outward from the

bottom center of the storm in the picture at left. In the picture at

right the cold air has moved further outward and has begun to

get in the way of the updraft. The updraft is forced to

rise earlier and a little ways away from the center of the

thunderstorm. Note how this rising air has formed an extra

lip of cloud. This is called a shelf cloud.

Here's a photograph of the dust stirred up by the thunderstorm

downdraft winds (blowing into Ahwatukee, Pheonix on Aug. 22,

2003). The thunderstorm would be off the left somewhere and

the dust front would be moving toward the right. Dust storms

like this are often called "haboobs" (source of this

image). We'll learn more about the hazards

associated with strong downdraft winds later in the semester when

we cover thunderstorms.

Shelf clouds can sometimes be quite impressive (the picture

above is from a

Wikipedia article on arcus clouds). The

main part of the thunderstorm would be to the left. Cold air

is moving from left to right in this picture. The shelf

cloud forms along the advancing edge of the gust front.

Here's the completed cloud chart

And here's a link to a cloud

chart on a National Weather Service webpage.