Mon., Feb. 17, 2014

Songs by Crooked Still "American Tune"

and a Robert Plant & Alison Krauss collaboration "Sister Rosetta

goes Before Us" while the Optional Assignment was being

collected before class this morning.

Answers to the Optional Assignment will appear online later today.

The 1S1P reports on radon

have been graded and were returned today. The Stratospheric

Ozone and Carbon Dioxide reports haven't been graded yet.

A new Optional

Assignment is now available and is your first chance to earn

a Green Card. The

assignment is due by the start of class next Monday, Feb. 24.

Quiz #1 is Wednesday this week. You'll find times and

locations of the two reviews at the end of the Quiz #1 Study Guide.

We need to finish our study of surface weather maps by trying

to located a warm front.

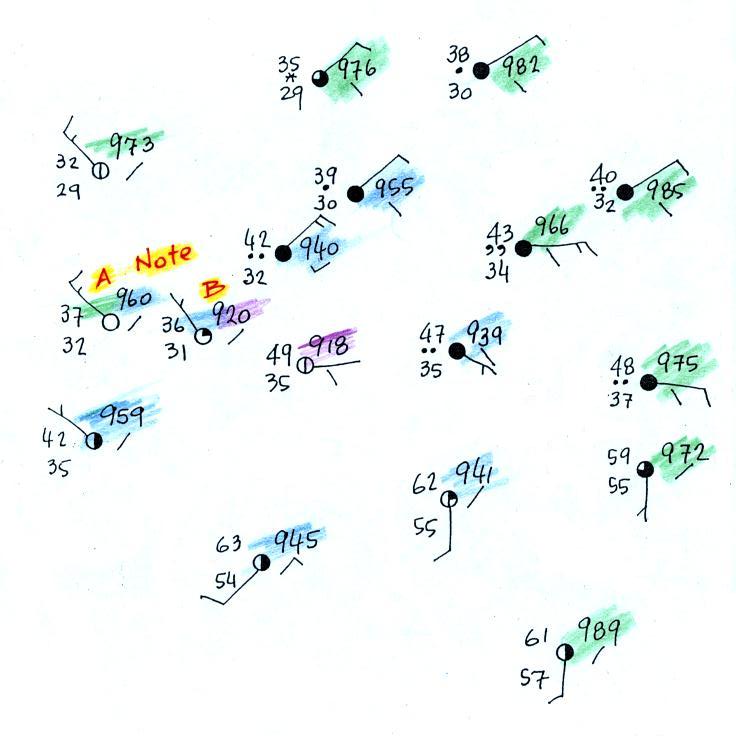

This is the map we will be working with (see p. 149b in the

ClassNotes). First though the figure below reviews some of

the weather conditions you would expect to find in front of and

behind a warm front.

Step #1

We'll start by drawing some isobars to map out the pressure

pattern. A partial list of allowed isobars is shown at the

right side of the map above (increments of 4 mb starting at 1000

mb). We've located located the highest and lowest pressure

values on the map. Then we choose allowed isobar values that

fall between these limits. In this case we'll need to draw

992 mb and 996 mb isobars.

Here's the map with color coded pressures. Pressures less

than 992 mb are purple,

pressures between 992 and 996 mb are blue,

and pressures greater than 996 mb are green.

Note that station B has a pressure of exactly 992.0 mb, the 992 mb

isobar will go through that station. The 996 mb isobar will

go through station A because it has a pressure of exactly 996.0

mb.

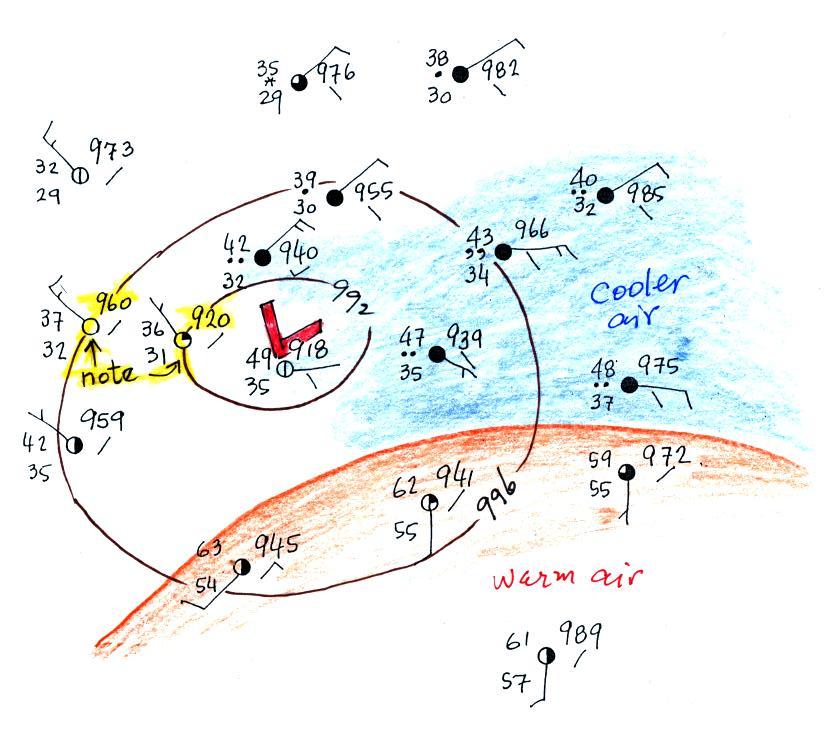

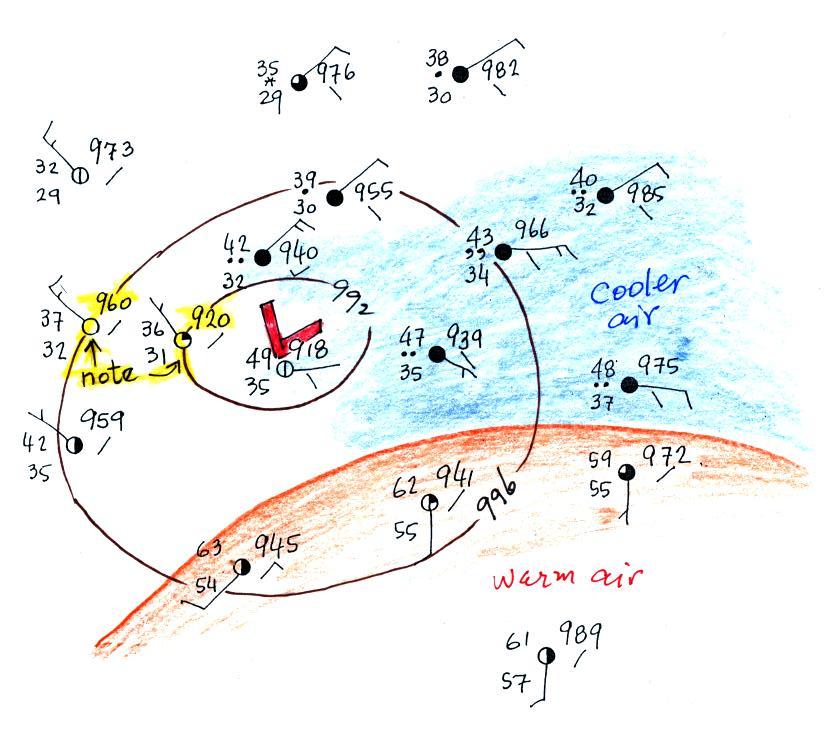

Here's the map with the isobars drawn in. On the map below

we use colors to locate the warm and cooler air masses.

Step #2

The warm air mass has been colored in orange. Cooler air

east of the low pressure center is blue. Can you see

where the warm front should go?

Step #3

Here's the map with a warm front drawn in (the map was redrawn so

that the edge of the warm (orange) air mass would coincide with

the warm front). The change in wind directions was probably

more noticeable that the temperature change. Most of the

cloud outlined in green are probably being produced by the warm

front. You can see how more extensive cloud coverage is with

a warm front.

Step #4

Two of the stations near the right edge of the picture and on

opposite sides of the front are redrawn below.

The station north of the front has cooler and drier air, winds are

from the east, skies are overcast and light rain is falling.

The pressure is falling as the warm front approaches. These

are all things you'd expect to find ahead of a warm front.

Behind the front at the southern station pressure is rising, the

air is warmer and moister, winds have shifted to the south and the

skies are starting to clear.

Step #5

Finally it's worth looking at the left, western, side of the

map. There's pretty good evidence of a cold front.

There's a big temperature change (low 60s to low 40s and 30s)

and a very noticeable wind shift (SW ahead of the cold front and

NW behind).

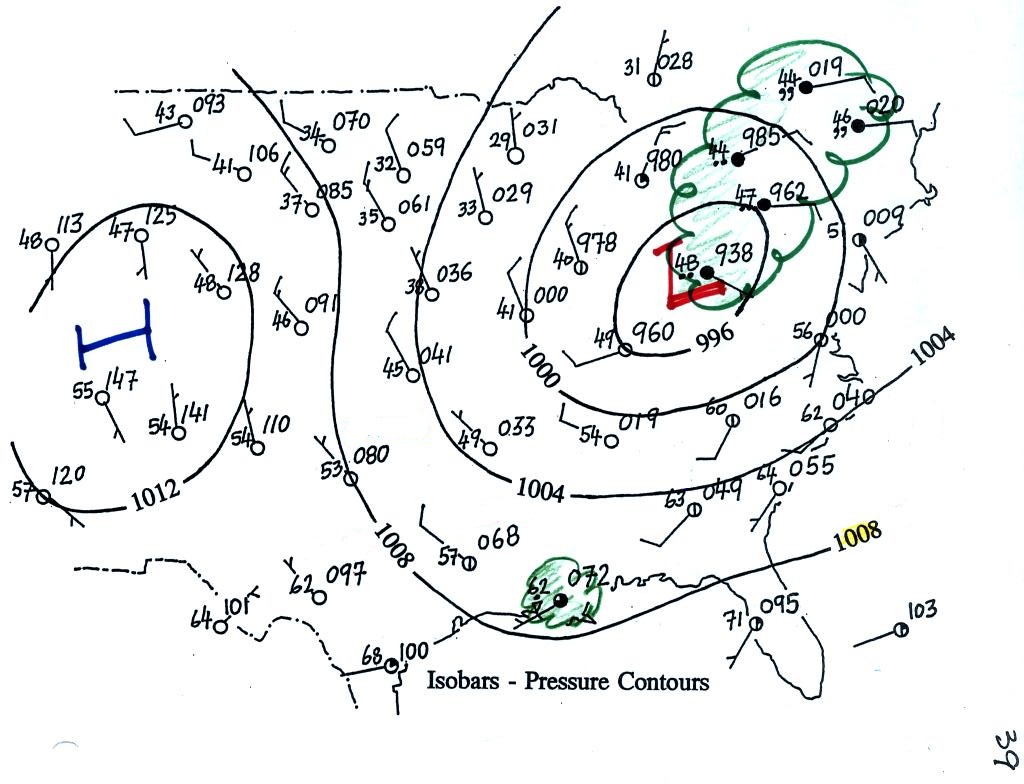

We need to go back to the figure

where this mostly all began

After learning how weather data are plotted on a map using the

station model notation we found that the data,, by themselves,

were not enough to really be able to say what was causing the

cloudy, rainy weather in the NE and along the Gulf Coast.

We added some isobars to reveal the pressure pattern and to

locate large centers of high and low pressure. Winds

converging into the center of low pressure cause air to rise and

might be part of the explanation for the unsettled weather in the

NE. That would explain the rain shower along the Gulf Coast

however.

Now we've added cold and warm fronts to the picture. The

approaching cold front is almost certainly the cause of the shower

along the Gulf Coast. The clouds in the NE are probably

being produced by the warm front.

Up to this point we've been learning about surface

weather maps. Maps showing conditions at various altitudes

above the ground are also drawn. Upper level conditions can

affect the development and movement of surface features (and vice

versa).

Here we'll mostly just learn 3 basic facts about upper level

charts. The Optional

Assignment that I mentioned in class will go much further

than we went in class.

First the overall appearance is somewhat different from a

surface weather map. The pattern on a surface map can be

complex and you generally find circular (more or less) centers

of high and low pressure (see the bottom portion of the figure

below). You can also find closed high and low pressure

centers at upper levels, but mostly you find a relatively simple

wavy pattern like is shown on the upper portion of the figure

below (sort of a 3-dimensional view). You'll find this

basic picture on p. 41 in the ClassNotes.

A simple upper

level chart pattern is sketched below (a map view).

There are two basic features: wavy lines that dip southward

and have a "u-shape" and

lines that bend northward and have an "n-shape".

The u-shaped portion

of the pattern is called a trough. The n-shaped portion is called

a ridge.

Troughs are produced by large volumes of cool or cold

air (the cold air is found between the ground and the upper

level that the map depicts). The western half of the

country in the map above would probably be experiencing colder

than average temperatures. Large volumes of warm or hot

air produce ridges. You can find out why this is true by

reading "Upper level

charts pt. 2".

The winds on

upper level charts blow parallel to the contour lines

generally from west to east. This is a little different

from surface winds which blow across the isobars toward low

pressure. An example of surface winds is shown below.

That's it for this first

section. Really all you need to be able to do is

1. identify troughs and ridges,

2. remember that troughs are associated with cold air &

ridges with warm air, and

3. remember that upper level winds blow parallel to the

contour lines from west to east.

The next two figures weren't discussed quickly in

class. They go beyond what you will near to worry

about on this week's quiz. I've included them here

just to give you some idea of the interaction between

weather at ground level and conditions above the ground.

Here's the earlier picture again overlaying surface and

upper-level maps.

On the surface map above you see centers

of HIGH and LOW pressure. The surface low pressure

center, together with the cold and warm fronts, is a

middle latitude storm.

Note how the counterclockwise winds spinning around the

LOW move warm air northward (behind the warm front on the

eastern side of the LOW) and cold air southward (behind

the cold front on the western side of the LOW).

Clockwise winds spinning around the HIGH also move warm

and cold air. The surface winds are shown with thin

brown arrows on the surface map.

Note the ridge and trough features on the upper level

chart. We learned that warm air is found below an

upper level ridge. Now you can begin to see where

this warm air comes from. Warm air is found west of

the HIGH and to the east of the LOW. This is

where the two ridges on the upper level chart are also

found. You expect to find cold air below an upper

level trough. This cold air is being moved into the

middle of the US by the northerly winds that are found

between the HIGH and the LOW.

Note the yellow X marked on the upper level chart directly

above the surface LOW. This is a good location for a

surface LOW to form, develop, and strengthen

(strengthening means the pressure in the surface low will

get even lower than it is now. This is also called

"deepening"). The reason for this is that the yellow

X is a location where there is often upper level

divergence. Similary the pink X is where you often

find upper level convergence. This could cause the

pressure in the center of the surface high pressure to get

even higher. You can read more about this in Upper level charts

pt. 3. The upper level

winds could also cause the surface storm to weaken (the low

pressure would get higher).

.

One of the things we have learned about surface

LOW pressure is that the converging surface winds create rising

air motions. The figure above gives you an idea of what

can happen to this rising air (it has to go somewhere).

Note the two arrows of air coming into the point "DIV" and three

arrows of air leaving (more air going out than coming in), this

is upper level divergence). The rising air can, in effect,

supply the extra arrow's worth of air.

Three arrows of air come into the point marked "CONV" on the

upper level chart and two leave (more air coming in than going

out = upper level convergence). What happens to the extra

arrow? It sinks, it is the source of the sinking air found

above surface high pressure.