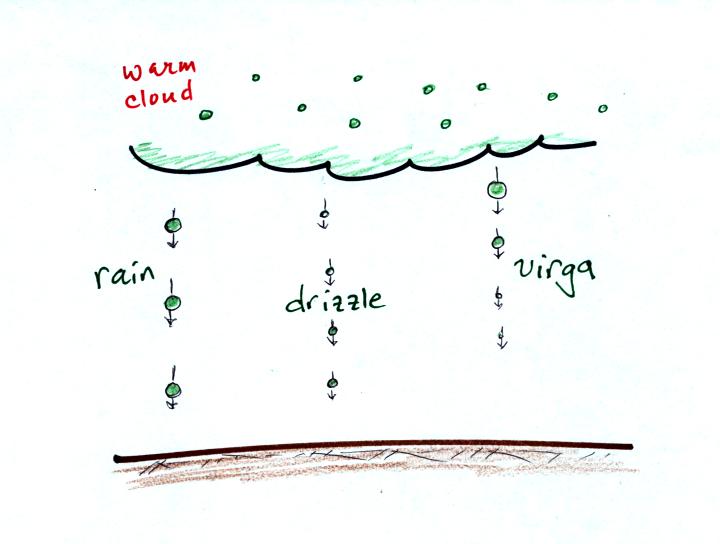

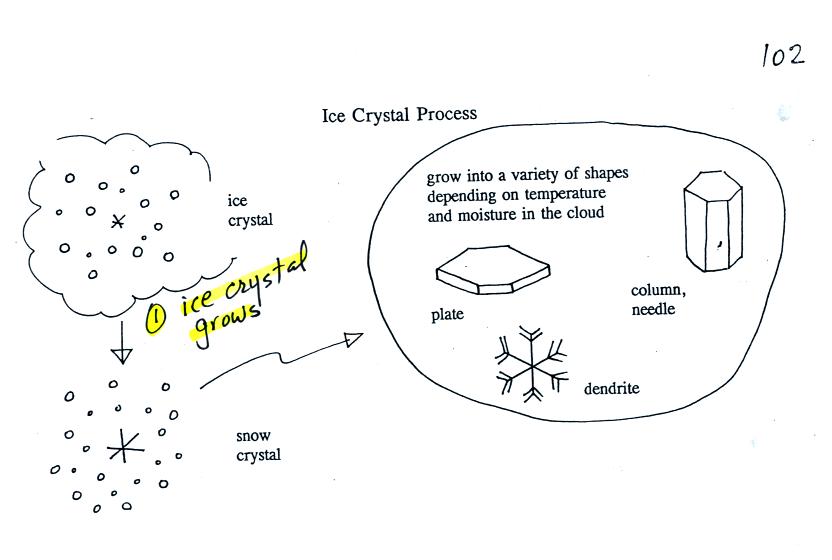

The ice crystal process

is a

whole lot more interesting because of the variety of different types of

precipitation that it can produce. Much of what is shown above

happens inside the cloud, some of it happens after the particles leave

the cloud and fall toward the ground.

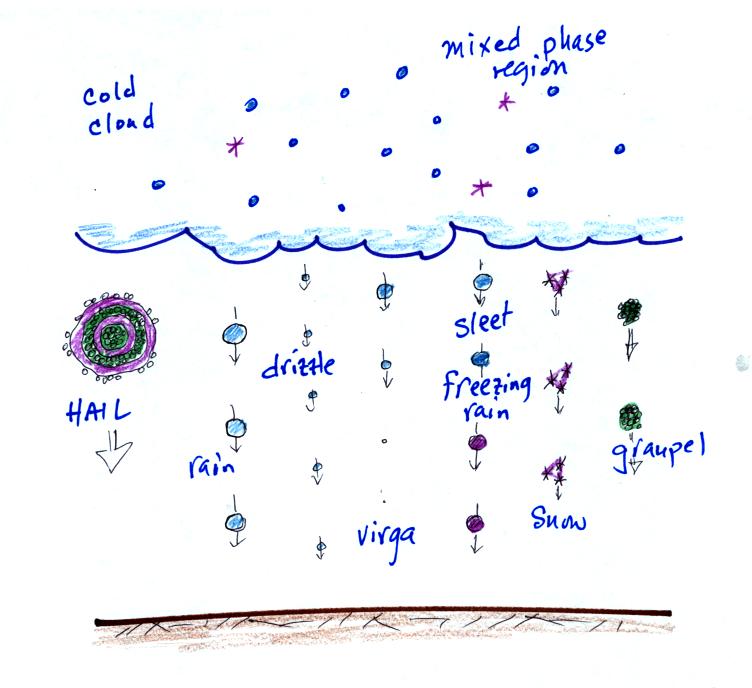

Before

learning about the ice

crystal process, we need to first look at the structure of cold

clouds.

The figure below is a redrawn version of what was shown in class.

The bottom of the thunderstorm, Point 1, is warm

enough

(warmer than freezing) to just

contain water

droplets. The top of the thunderstorm, Point 2, is colder than

-40 C (also -40 F) and just contains ice crystals. The

interesting part of the

thunderstorm and the

nimbostratus cloud is the middle part, Point 3, that contains both

supercooled water

droplets (water that has

been cooled to below freezing but hasn't frozen) and ice

crystals.

This is called the mixed phase

region. This is where the ice crystal process will be able

to produce

precipitation. This is also where the electrical charge that

results in lightning is generated.

The supercooled water droplets aren't able to freeze even though

they

have been cooled below freezing. At Point 4 we see this is

because it is much

easier for small droplets of water to freeze onto an ice crystal

nucleus or for water vapor to be deposited onto an ice crystal nucleus

(just like it is easier for water vapor to condense onto

condensation nuclei rather than condensing and forming a small droplet

of pure water). Not just any material will work as an ice nucleus

however. The material must have

a crystalline structure that is like that of ice. There just

aren't very many materials with this property and as a result ice

crystal nuclei are rather scarce.

We'll see

next how the ice crystal process works. There are a couple of

"tricky" parts.

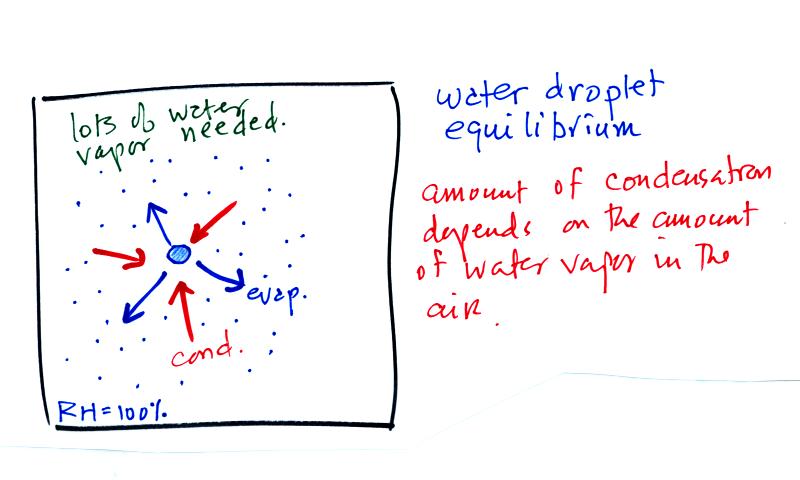

The first figure above (see p.101 in the photocopied

Class

Notes)

shows a water droplet in equilibrium with its surroundings..The droplet

is evaporating (the 3 blue arrows in the figure). The rate of

evaporation will depend on the temperature of the water droplet.

The droplet is surrounded by air that is saturated with water vapor

(the droplet is inside a cloud where the relative humidity is

100%). This means there is enough water vapor to be able to

supply 3 arrows of condensation. Because the droplet loses and

gains water vapor at equal rates it doesn't grow or shrink.

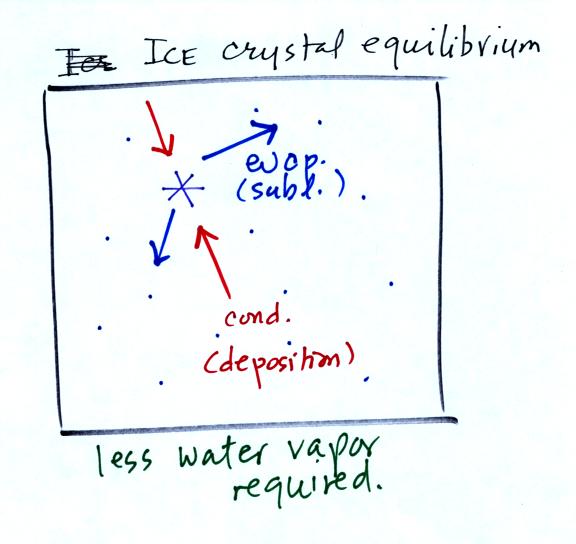

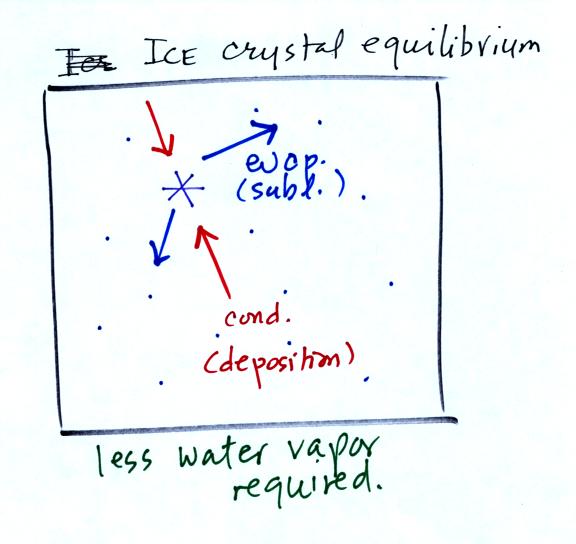

This figure shows what is required

for an ice crystal (at

the same

temperature) to be in equilibrium with its surroundings. First,

the ice crystal won't evaporate as rapidly as the water droplet (only

two arrows are shown). Going from ice to water vapor is a bigger

jump than going from water to water vapor. There won't be as many

ice molecules with enough energy to make that jump. A sort of

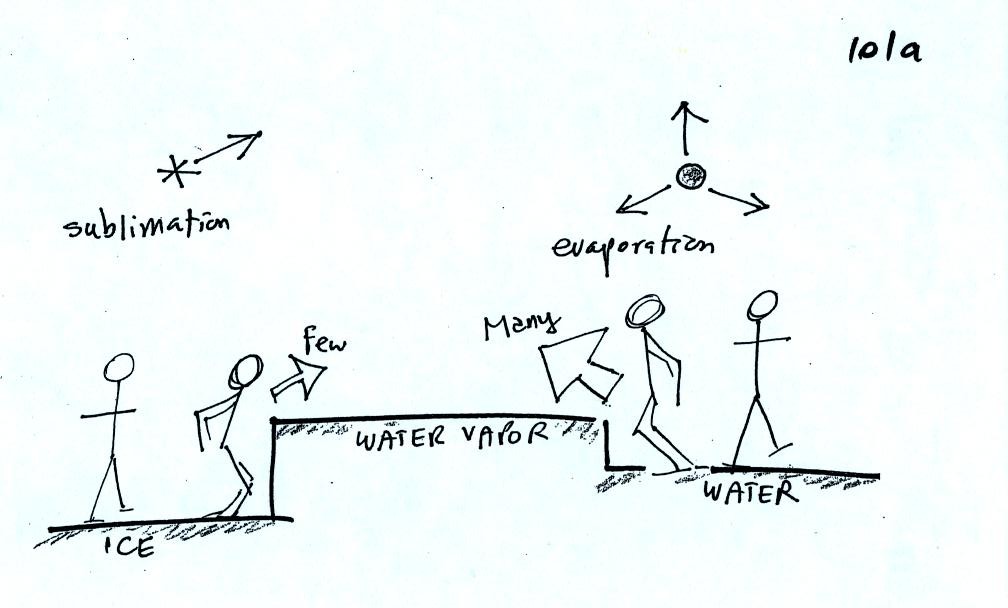

analogous situation is shown in the figure below. The class

instructor could with a little warmup and practice jump from the floor

up and onto the seat of a chair (maybe 15 inches tall). Trust me,

he could, and so could most of the people in the room. The class

instructor does some stupid things in class, but he wouldn't begin to

consider trying to jump from the floor up to the top of the cabinet (30

inches or more).

To be in equilibrium only two arrows of condensation are

needed.

There doesn't need to be as much water vapor in the air surrounding the

ice crystal to supply this lower rate of condensation.

There are going to be fewer people able to make the

big jump on

the

left just as there are fewer ice molecules able to sublimate.

Going from water to water vapor is a "smaller jump" and more molecules

are able to do just as more people would be able to make the shorter

jump at right in the picture above.

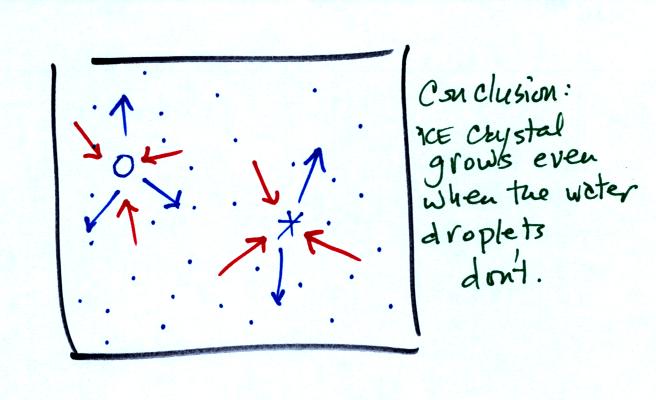

Now what happens in the mixed phase region of a cold cloud

is that

ice crystals find themselves in the very moist surroundings needed for

water droplet equilibrium. This is shown below.

The water droplet is in equilibrium (3 arrows of evaporation

and 3

arrows of condensation) with the surroundings. The ice crystal is

evaporating more slowly than the water droplet. Because the ice

crystal is in the same surroundings as the water droplet water vapor

will be condensing onto the ice crystal at the same rate as onto the

water droplet. The ice

crystal isn't in equilibrium, condensation

(3 arrows) exceeds evaporation (2 arrows) and the ice crystal will

grow. That's

what makes the ice crystal process work.

The equal rates of condensation are shown in the figure

below using the

earlier analogy.

Even though he was afraid to try to jump up to the top

of

the counter, the instructor could jump from the counter to the floor.

Now

we will see what can happen once the ice crystal has had a chance to

grow a little bit.

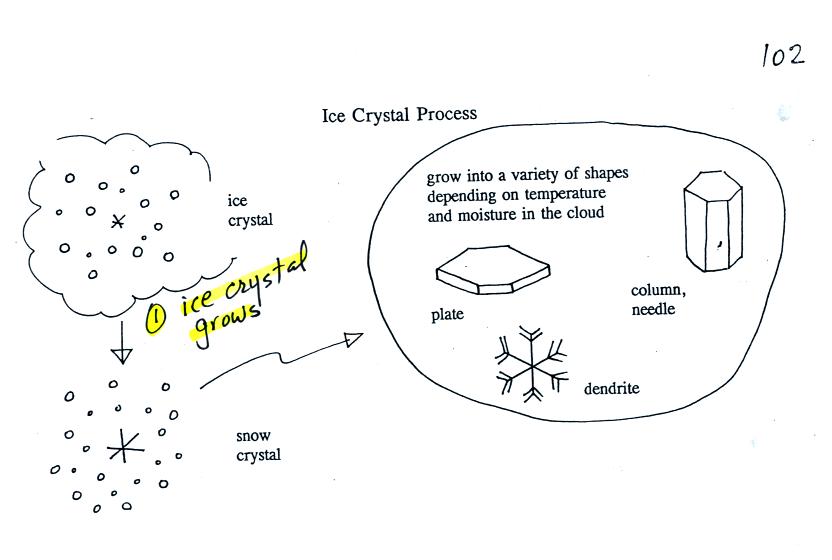

Once an ice

crystal has grown a

little bit it becomes a snow crystal (this figure is on p. 102 in the

photocopied classnotes). Snow crystals can have a variety of

shapes

(plates, dendrites, columns, needles, etc.; these are called crystal

habits) depending on the conditions (temperature and

moisture)

in the cloud. Dendrites are the most common because they form

where there

is the most moisture available for growth. With more raw material

available it makes sense there would be more of this particular snow

crystal

shape.

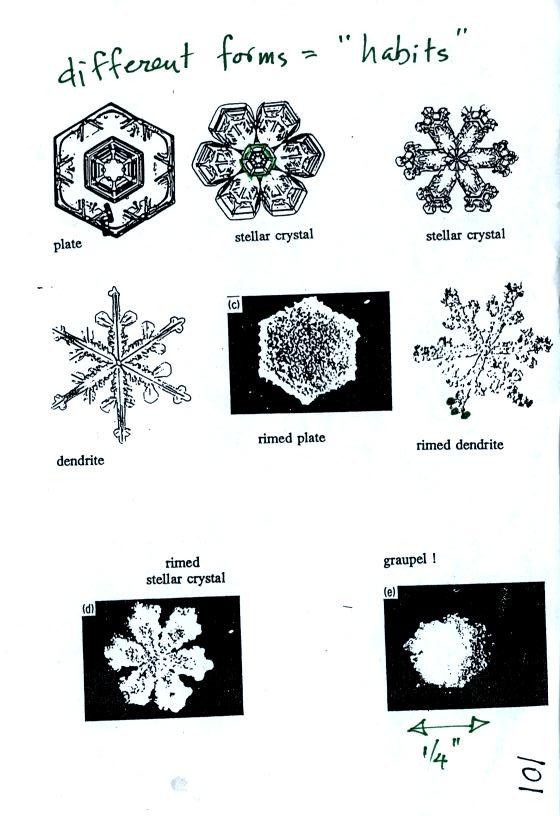

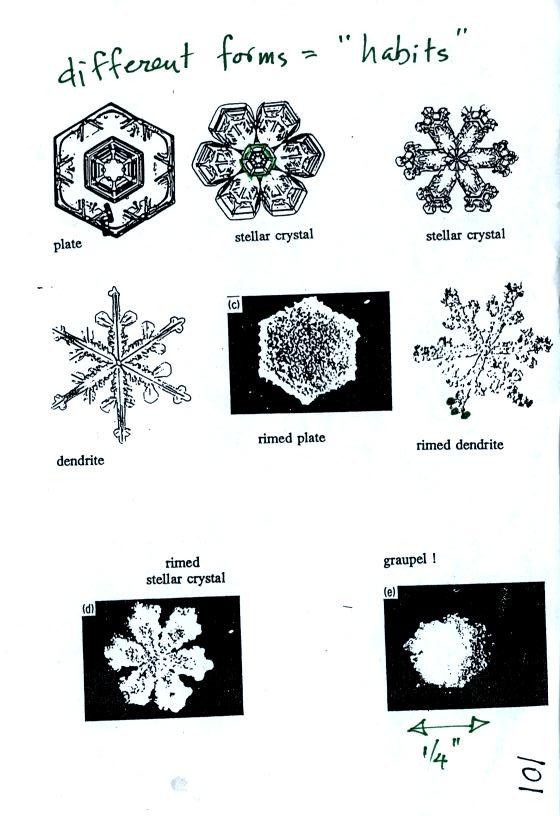

Here are some actual photographs of snow crystals (taken with a

microscope). Snow crystals are usually 100 or a few 100s of

micrometers

in diameter (tenths of a millimeter in diameter).

You'll find some much better photographs and a pile of addtional

information

about snow crystals at www.snowcrystals.com

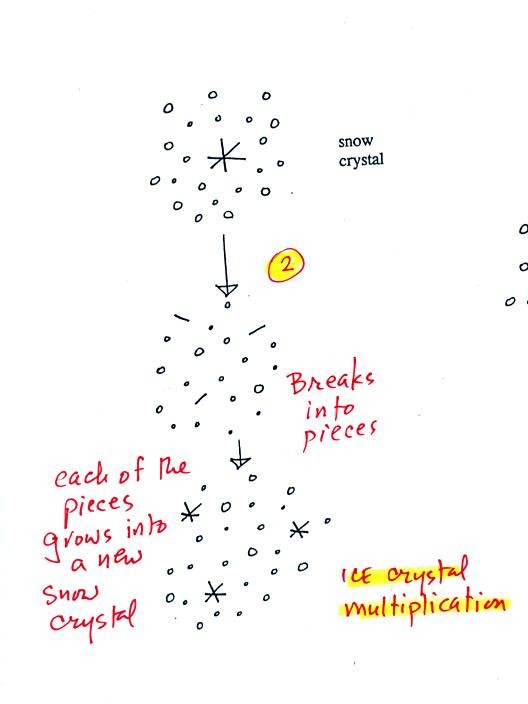

A

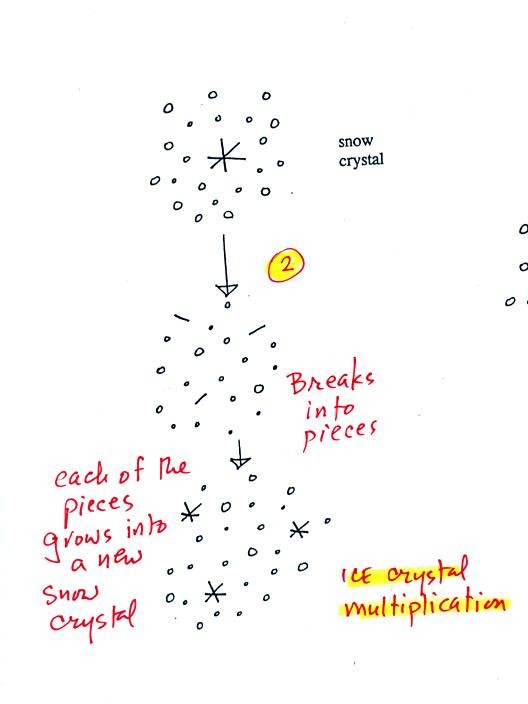

variety of things can happen once a snow crystal forms. First it

can

break into pieces, then each of the pieces can grow into a new snow

crystal. Because snow crystals are otherwise in rather short

supply, ice

crystal multiplication is a way of increasing the amount of

precipitation that

ultimately falls from the cloud.

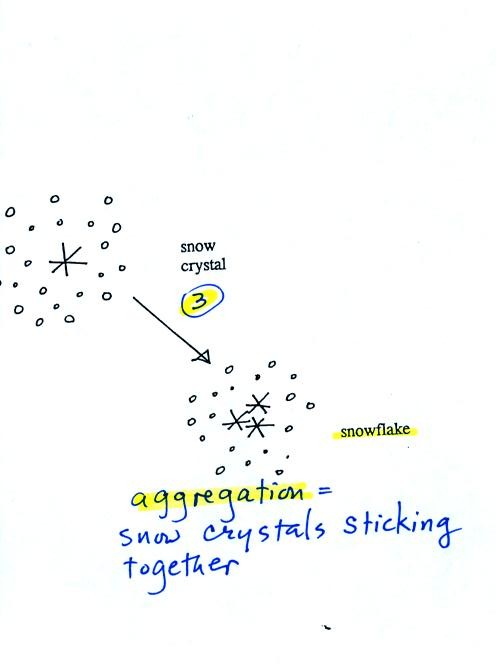

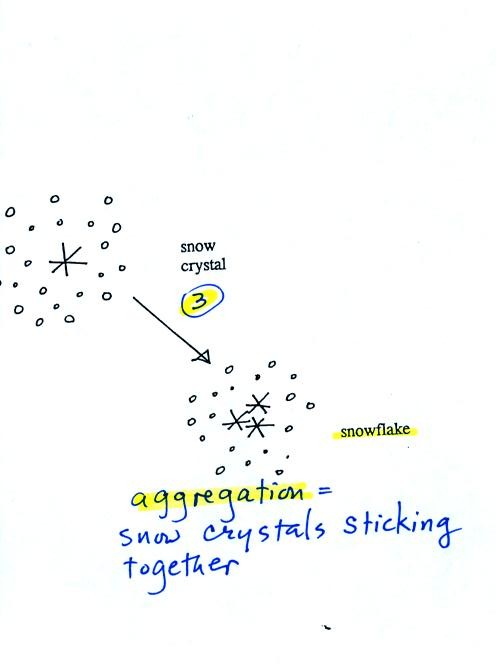

Several snow

crystals can collide

and stick together to form a snowflake. Snow crystals are small,

a few

tenths of a millimeter across. Snowflakes can be much larger and

are made

up of many snow crystals stuck together. The sticking together or

clumping together of snow crystals is called aggregation.

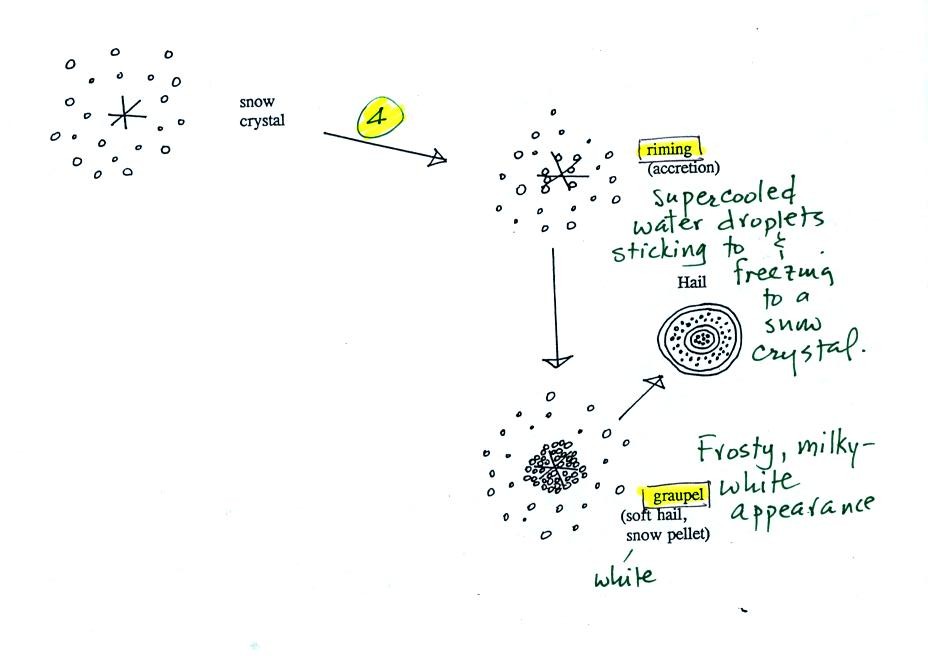

Snow crystals can

collide with supercooled water droplets. The

water

droplets may stick and freeze to the snow crystal. This process

is called

riming or accretion (note it is really the same idea as collision and

coalescence). If a snow crystal collides with enough water

droplets it

can be completely covered with ice. The resulting particle is

called

graupel (or snow pellets). Graupel is sometimes mistaken for hail

and is

called soft hail or snow pellets. Rime ice has a frosty milky

white

appearance. A graupel particle resembles a miniature snow

ball.

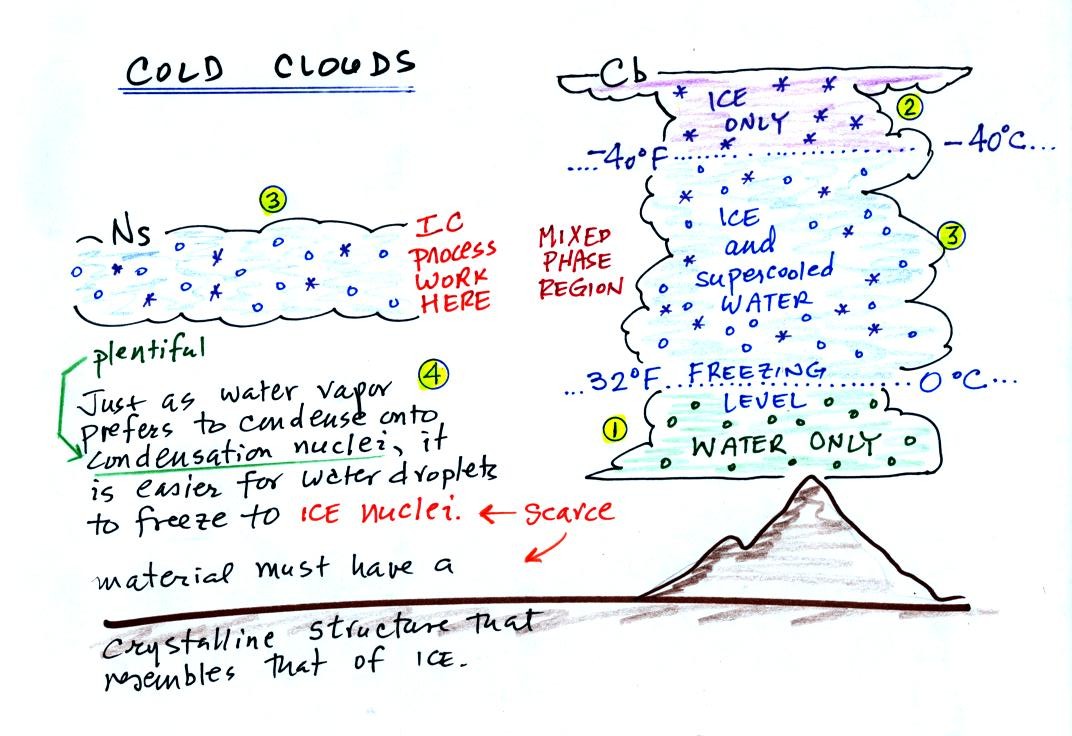

Graupel particles often serve as the nucleus for a hailstone.

This figure gives you an idea of how hail forms.

In the figure

above a hailstone

starts with a graupel particle (Pt. 1, colored green to represent rime

ice). The

graupel falls or gets carried into a part of the cloud where it

collides with a

large number of supercooled water droplets which stick to the graupel

but don't

immediately freeze. The graupel gets coated with a layer of water

(blue) at Pt. 2. The particle then moves into a colder part of

the cloud

and the

water layer freeze producing a layer of clear ice (the clear ice,

colored

violet, has a distinctly different appearance from the milky white rime

ice), Pt. 3. In Tucson this is often the only example of hail that you

will see:

a graupel particle core with a single layer of clear ice.

In the severe thunderstorms in the Central Plains, the hailstone can

pick up a

new layer of rime ice, followed by another layer of water which

subsequently

freezes to produce a layer of clear ice.

This cycle can repeat several times; large hailstones can be composed

of many

alternating layers of rime and clear ice. An unusually

large

hailstone (around 3 inches in diameter) has been cut in half to show

(below)

the different layers of ice.

Hail is produced

in strong

thunderstorms with tilted updrafts. You would never see hail

falling from a nimbostratus cloud. The figure below wasn't shown

in

class.

The growing

hailstone can fall

back into the updraft (rather than falling out of the cloud) and be

carried

back up toward the top of the cloud. In this way the hailstone

can

complete several cycles through the interior of the cloud.

Students in

class today were given the option of answering the questions below and

turning in their answers at the end of class for a little bit of extra

credit.

Here are the

questions and the answers:

1. Dendrites, plates, and columns are all names of

different types of snow crystals.

2. Several snow crystals sticking together

would form

a. hail

b. graupel

c. sleet

d. snow

3. The largest raindrops are only about 5 or 6 mm (~ 1/4

inch) in diameter. What frozen precipitation particle can get

much larger

than this? Hail.

4. How many 20 micrometer diameter cloud droplets would be

needed to make one 200 micrometer diameter drop of drizzle? The

200 micrometer drizzle droplet is 10 times bigger across than the 20

micrometer cloud droplet. Volume is length x width x height. So

there is a factor of 10 x 10 x 10 = 1000 times difference in

volume.

5. Is most of the rain in Tucson produced by the

COLLISION-COALESCENCE or the ICE

CRYSTAL process?

6. Which of the following is found in the greatest amounts

in the mixed-phase region of a

cold cloud?

a. ice crystal nuclei

b. ice crystals c. supercooled

water droplets d. graupel

7. What differences are there between condensation nuclei

and ice crystal nuclei? Ice

nuclei are much less abundant than condensation nuclei. Ice

nuclei must have a crystalline structure resembling ice. The same

requirement doesn't apply to condensation nuclei.

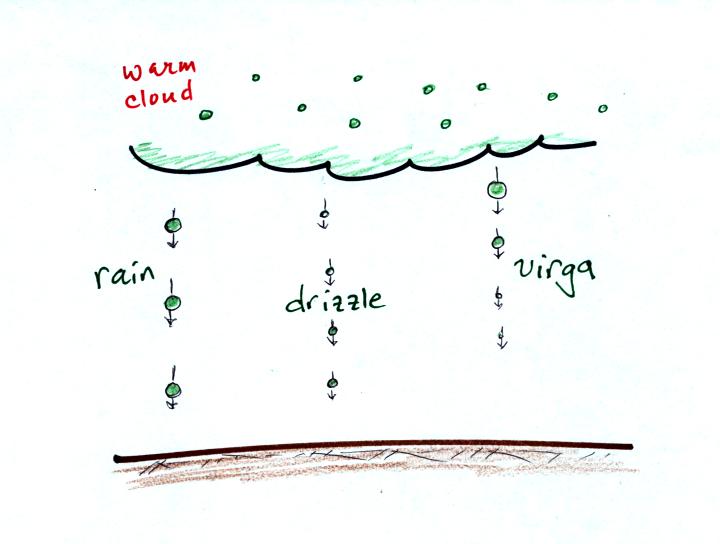

8. What is virga?

Rain or drizzle that evaporates

before reaching the ground.