If you replace the stack of bricks

with a people pyramid you

can understand that air pressure pushes upward as well as downward (it

also

pushes sideways)

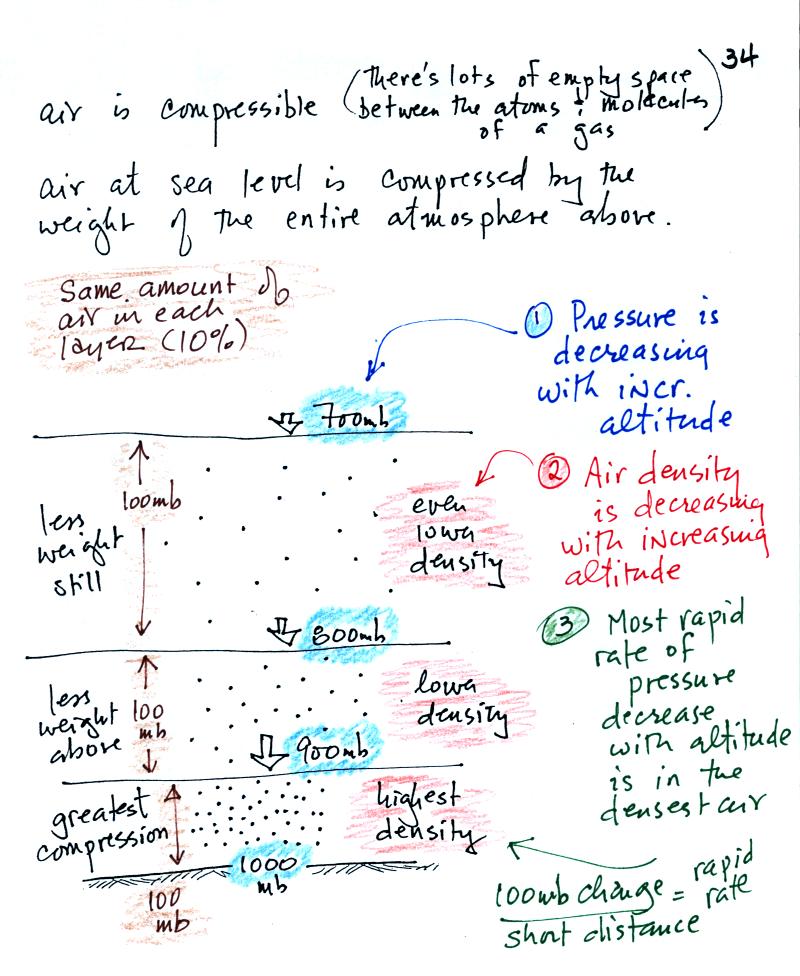

Because air is compressible, now we'll use a pile of mattresses

(clean ones, not the disgusting

things you see at the curb in front of peoples homes) to help

understand that air density decreases with

increasing altitude.

Here's a more clearly drawn version of the figure were used

in class.

There's a lot of information in

this figure. It is worth

spending a minute or two looking at it and thinking about it.

1. You can first notice and remember that pressure

decreases

with increasing altitude. 1000 mb at the bottom decreases to 700

mb at the top of the picture.

Each layer of air contain the same amount (mass) of air. You

can

tell because the pressure decrease as you move upward through each

layer is the same (100 mb). Each layer contains 10% of the air in

the atmosphere and has the same weight.

2. The densest air is found in the bottom

layer. That is because each layer has the same amount of air

(same mass). The bottom layer is compressed the most so it is the

thinnest layer and has

the

smallest volume. Mass/( small volume)

gives a high density. The top layer has the same amount of air

but about twice the volume. It therefore has a lower density.

3. You again notice something that we covered earlier: the most

rapid

rate of pressure decrease with increasing altitude is in the densest

air in the bottom air layer. It takes almost twice the distance

for pressure to decrease from 800 mb to 700 mb in the top most layer

where the air density is lower.

Pressure decreases with increasing altitude, so does

density. What about temperature? Our

experience tells us that temperature decreases with increasing

altitude. This is what people thought was true throughout the

atmosphere up until about 1900. Then they start sending balloons

up to high altitudes in the atmosphere to measure temperature.

They were surprised

when they found that temperature stopped decreasing at an altitude of

about 10 km. Temperature actually began to increase at altitudes

above 20 km.

We had a quick look at how air temperature changes

with

altitude. The figure drawn in

class has been split into two parts and redrawn for

improved

clarity (actually this is a figure from the Fall 2008 semester).

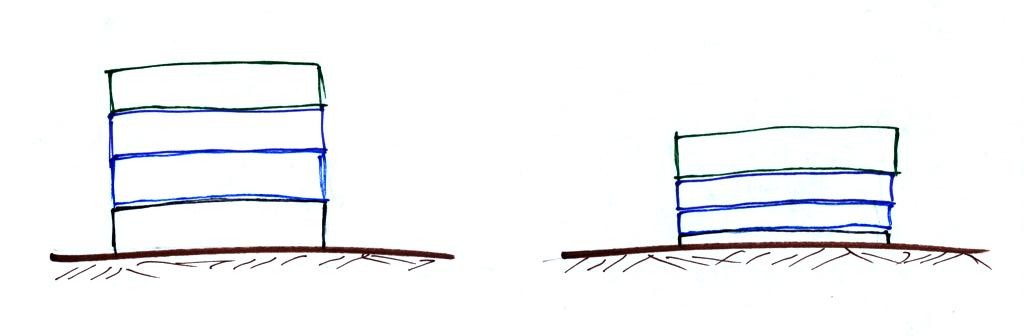

The atmosphere can be split

into layers

depending on whether

temperature is increasing or decreasing with increasing altitude.

The two lowest layers are shown in the figure above. There are

additional layers (the mesosphere and the thermosphere) above 50 km but

we won't worry about them.

1. We live in

the troposphere. The troposphere is found, on average, between 0

and about 10 km altitude, and is where temperature usually decreases

with

increasing altitude. [the troposphere is usually a little higher

in the tropics and lower in the cold air at polar latitudes]

The troposphere contains most of the water vapor

in the atmosphere (the water vapor comes from evaporation of ocean

water) and is

where most of the clouds and weather occurs. The

troposphere can be stable or unstable (tropo means to turn over and

refers to the fact that air can move up and down in the

troposphere).

2a. The thunderstorm shown in

the figure indicates unstable conditions, meaning that strong up and

down air motions are occurring. When the thunderstorm reaches the

top of the troposphere, it runs into the bottom edge of the

stratosphere which is a very stable layer. The

air can't continue to rise into the stratosphere so the cloud

flattens out and forms an anvil (anvil is the name given to the flat

top of the thunderstorm). The

flat anvil top is something

that you can go outside and see and often marks the top of the

troposphere.

2b. The summit of Mt. Everest is a little over 29,000

ft. tall and is

close to the top of the troposphere.

2c. Cruising altitude in a passenger jet is usually between

30,000 and 40,000, near or just above the top of the troposphere, and

at the bottom of the stratosphere.

3. Temperature remains constant between 10 and 20 km

and then

increases with increasing altitude between 20 and 50 km. These

two sections form the stratosphere. The stratosphere is a

very stable air layer. Increasing temperature with increasing

altitude is called an

inversion. This is what makes the stratosphere so stable.

4. A kilometer is one

thousand meters. Since 1 meter is about 3 feet, 10 km is about

30,000 feet. There are 5280 feet in a mile so this is about 6

miles (about

is usually close enough in this class).

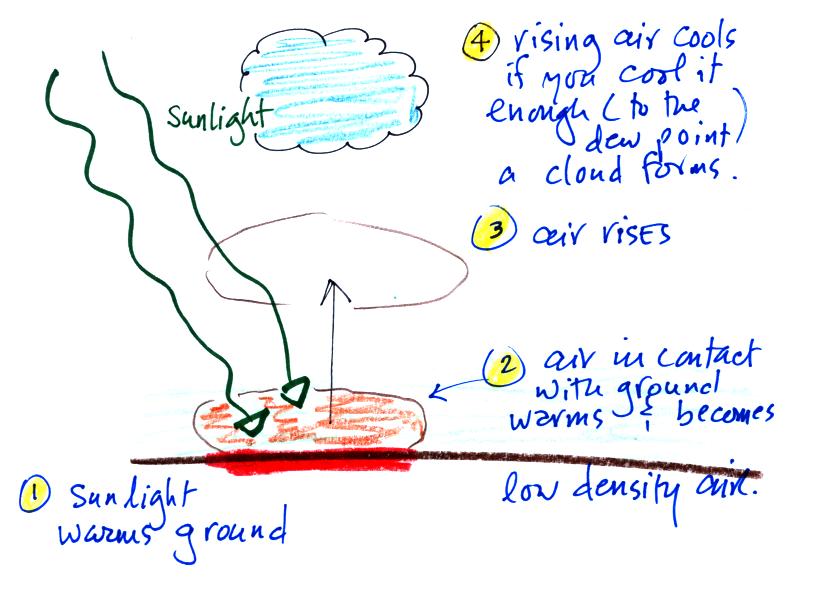

5. Sunlight is a mixture of ultraviolet (7%),

visible (44%), and

infrared light (49%). We can see the visible light.

5a. On average (over the globe and over the

course of a year) about 50% of the sunlight

arriving at the top of

the atmosphere passes through the atmosphere and is absorbed at the

ground (20% is absorbed by gases in the air, 30% is reflected back into

space). This warms the ground. The air in contact with the

ground is warmer than air just above. As you get further and

further from the warm ground,

the

air

is

colder

and

colder.

This

explains

why air temperature decreases with increasing altitude in the

troposphere.

5b. How do you explain increasing temperature with

increasing

altitude in the stratosphere.

The ozone layer is found in the stratosphere

(peak concentrations are found near 25 km altitude). Absorption

of

ultraviolet light by ozone warms the air in the stratosphere and

explains why the air can warm. The air in the stratosphere is

much less dense (thinner) than in the troposphere. So even though

there is not very much UV light in sunlight, it doesn't

take as much energy to warm this thin air as it would to warm denser

air closer to the ground.

6. That's a manned

balloon;

Auguste Piccard and Paul Kipfer are

inside. They were to first men to travel into the

stratosphere. It really was quite a daring trip at the time at

the

time,

and they very

nearly didn't survive it. We'll see a short video segment

documenting their trip before the Practice Quiz on Thursday.

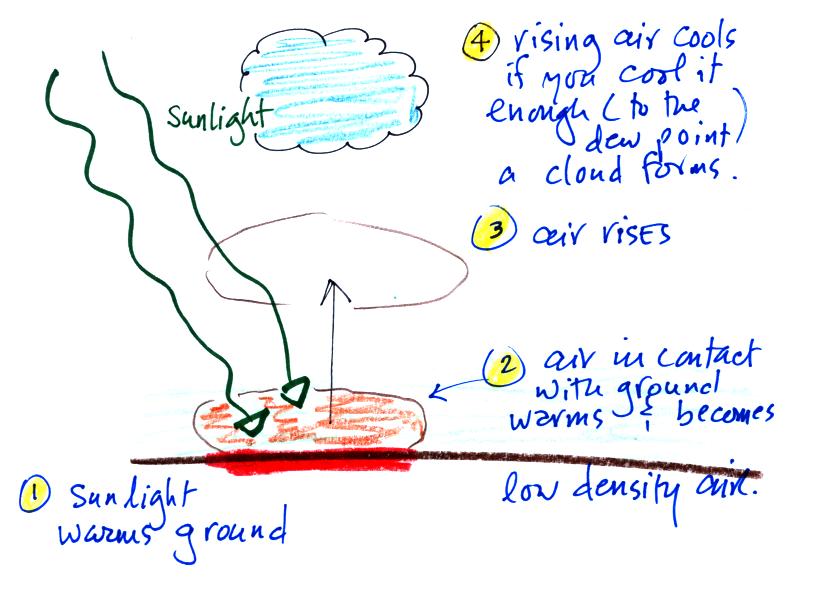

With the Experiment #1 reports due

next Tuesday, we need to cover the ideal gas law. This is also

the

first step in understanding why warm air rises and cold air

sinks.

Hot air balloons rise (they also

sink), so does the relatively

warm air in a thunderstorm (it's warmer than the air around

it). Conversely cold air sinks. The surface winds

caused by a thunderstorm downdraft (as shown above) can reach speeds of

100 MPH and are a serious weather hazard.

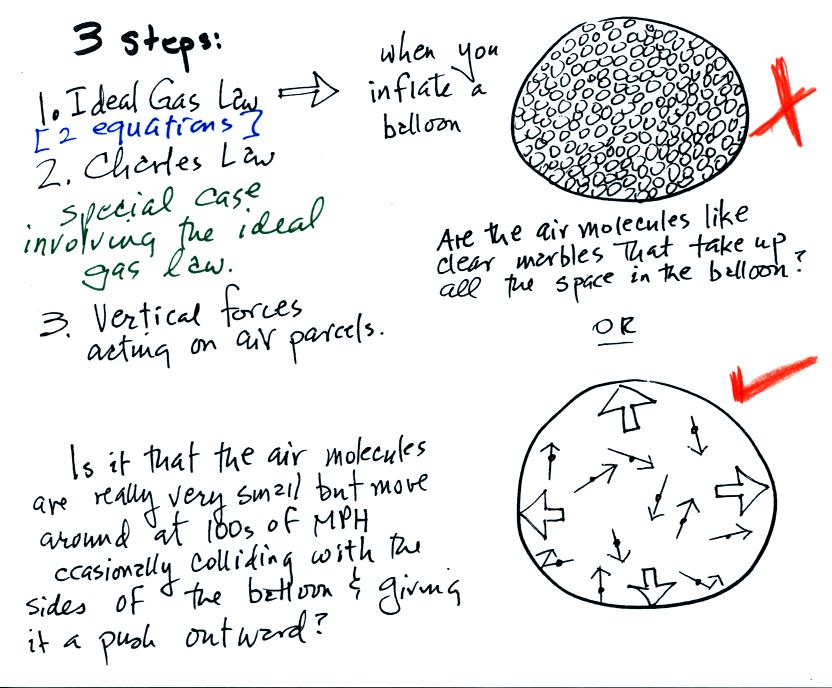

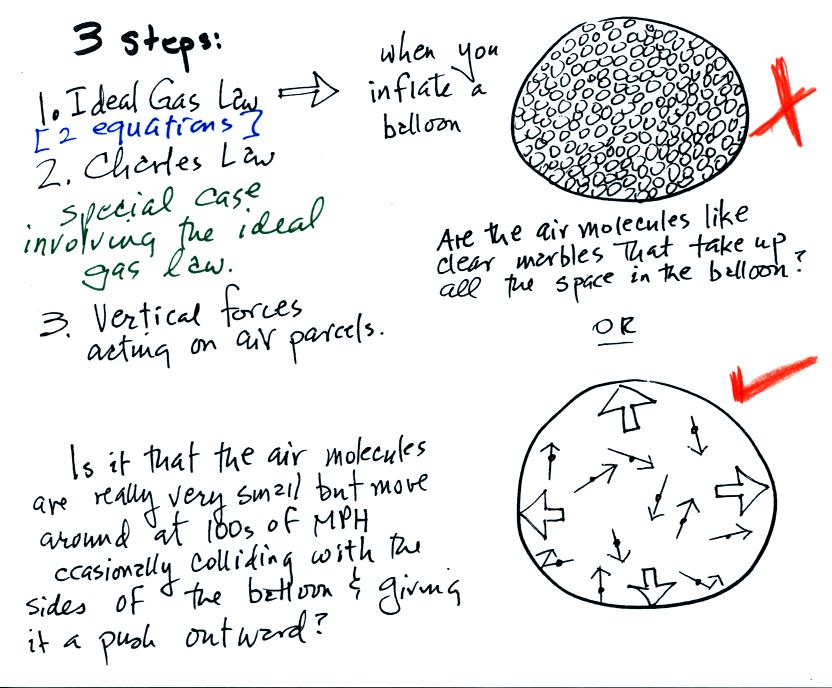

A full understanding of these rising and sinking motions is a

3-step process (the following is

from the bottom part of p. 49 in the photocopied ClassNotes)

We will first learn about the ideal

gas law.

That is an equation that tells you which/how properties of the air

inside a

balloon work to determine the air's pressure. Then we will look

at Charles' Law, a special situation involving the ideal gas law (air

temperature and density change together in a way that keeps the

pressure

inside a balloon constant). Then we'll look at the

two forces that determine whether a parcel of air will rise or

sink. Only the first section on the

ideal gas law will be covered on the Practice Quiz this week.

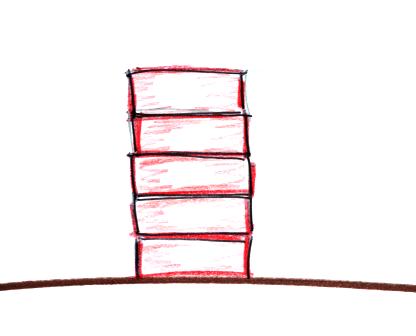

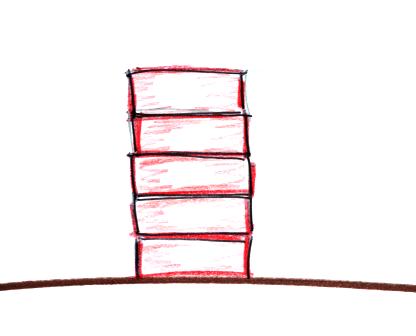

The figure above makes an important point: the air molecules in a

balloon "filled with air" really take up very little space. A

balloon filled with air is really mostly empty space. It is the

collisions of the air molecules with the inside walls of the balloon

that keep it inflated.

This figure wasn't

shown in class. Up to this point in the semester we

have been thinking of pressure as

being determined

by the weight of the air overhead. Air pressure pushes down

against the ground at sea level with 14.7 pounds of force per square

inch. If you imagine the weight of the atmosphere pushing down on

a balloon sitting on the ground you realize that the air in the balloon

pushes back with the same force. Air everywhere in the atmosphere

pushes upwards, downwards, and sideways.

The ideal gas law

equation is another way of thinking about air pressure, sort of a

microscopic scale version. We ignore

the atmosphere and concentrate on just the air inside the

balloon. We are going to "derive" an equation. Pressure (P)

will be on the left hand side. Properties of the air inside the

balloon will be found on the right side of the equation.

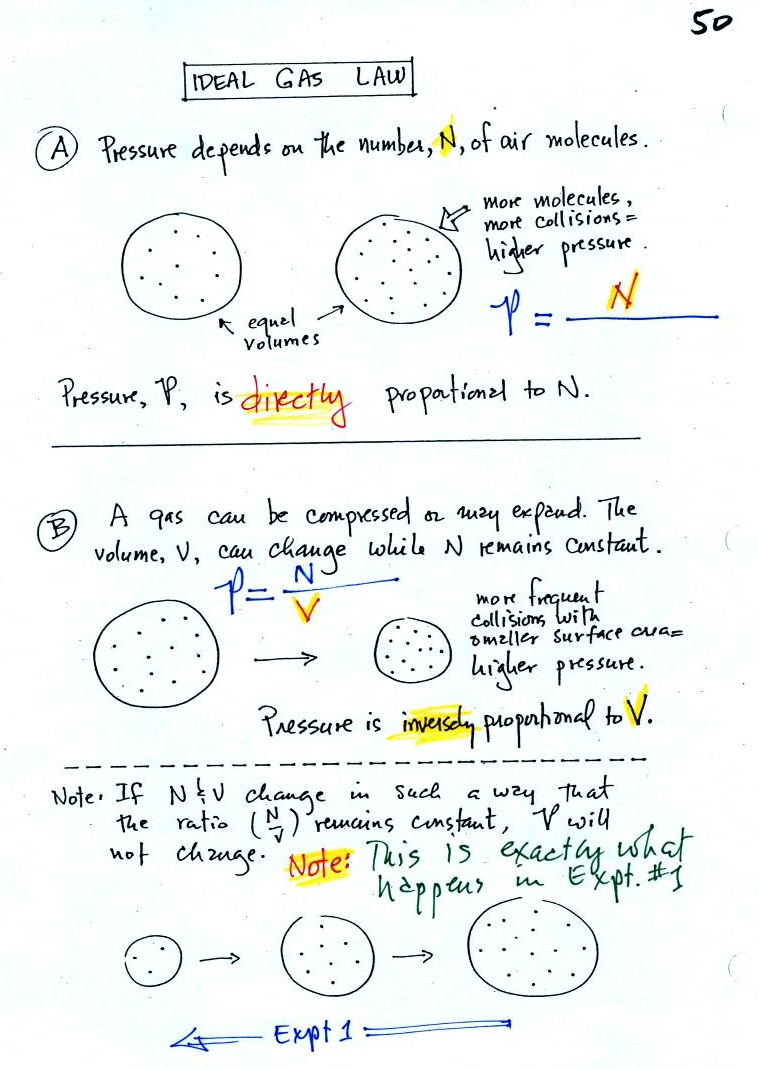

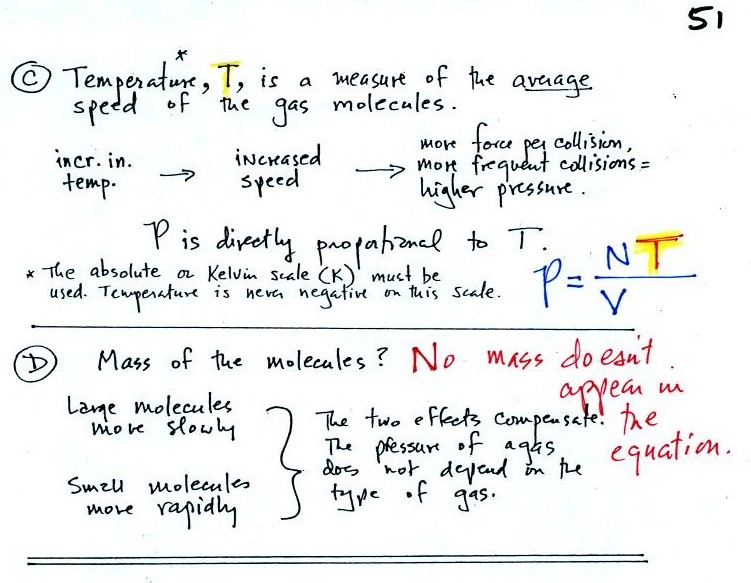

In A

the pressure produced by

the air

molecules inside a balloon will

first depend on how many air molecules are there, N. If there

weren't any air molecules at all there wouldn't be any

pressure. As you add more and more add to something like a

bicycle tire, the

pressure increases. Pressure is directly proportional to N - an

increase in N causes an increase in P. If N doubles, P also

doubles (as long as the other variables in the equation don't change).

In B

air pressure inside a balloon

also

depends on the size of the

balloon. Pressure is inversely proportional to volume, V

. If V were to double, P would drop to 1/2 its original value.

Note

it

is possible to keep pressure constant by changing N and V

together in just the right kind of way. This is what happens in

Experiment #1 that some students are working on. Oxygen in a

graduated cylinder reacts with steel wool to form rust. Oxygen is

removed from the air sample which is a decrease in N. As oxygen

is removed, water rises up into the cylinder decreasing the air sample

volume. N and V both decrease in the same relative amounts and

the air sample pressure remains constant.

If you were to remove 20% of the air molecules, V would decrease

to 20% of its original value and pressure would stay constant.

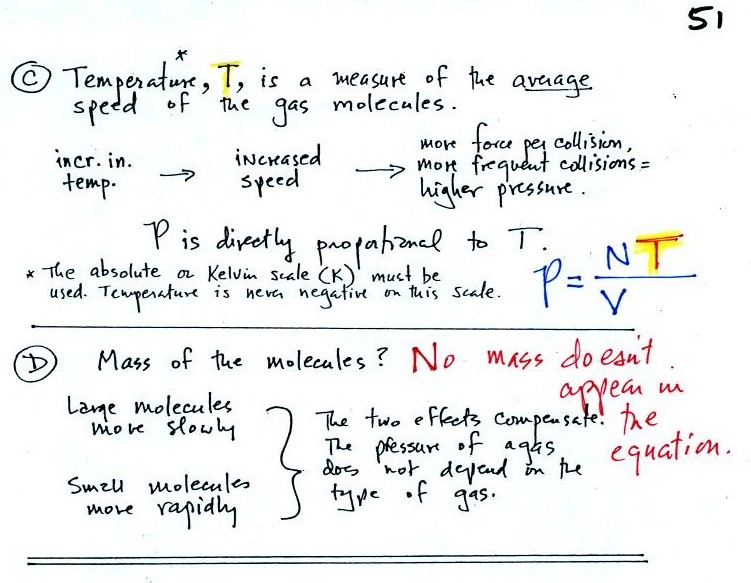

Part C: Increasing

the temperature of the gas in a balloon will cause the gas molecules to

move more quickly. They'll collide with the walls of the balloon

more frequently and rebound with greater force. Both will

increase the pressure. You shouldn't throw a can of spray paint

into a fire because the temperature will cause the pressure inside the

can to increase and the can could explode.

Surprisingly, as explained in Part

D,

the pressure

does

not depend on the mass of the

molecules. Pressure doesn't depend on the composition of the

gas. Gas molecules with a lot of mass will move slowly, the less

massive molecules will move more quickly. They both will collide

with the walls of the container with the same force.

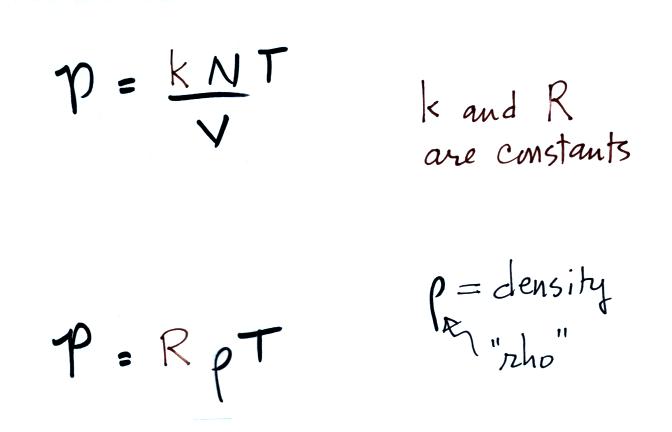

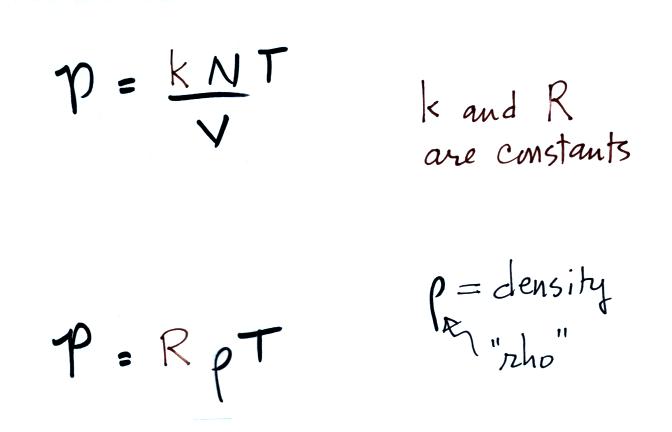

The figure below (which replaces the bottom of p. 51 in the

photocopied

ClassNotes) shows two forms of the ideal gas law. The top

equation is the one we just derived and the bottom is a second slightly

different version. You can

ignore the

constants k and R if you are just trying to understand how a change in

one of the variables would affect the pressure. You only need the

constants when you are doing a calculation involving numbers (which we

won't be doing).

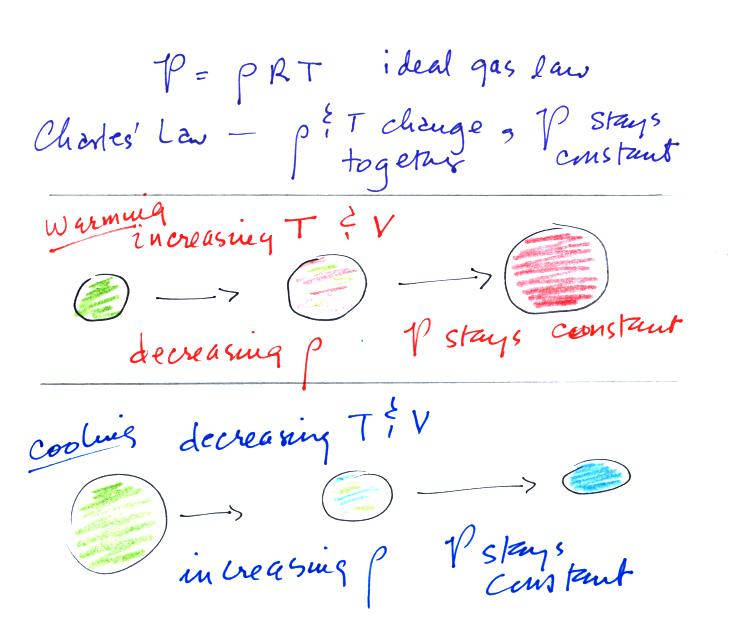

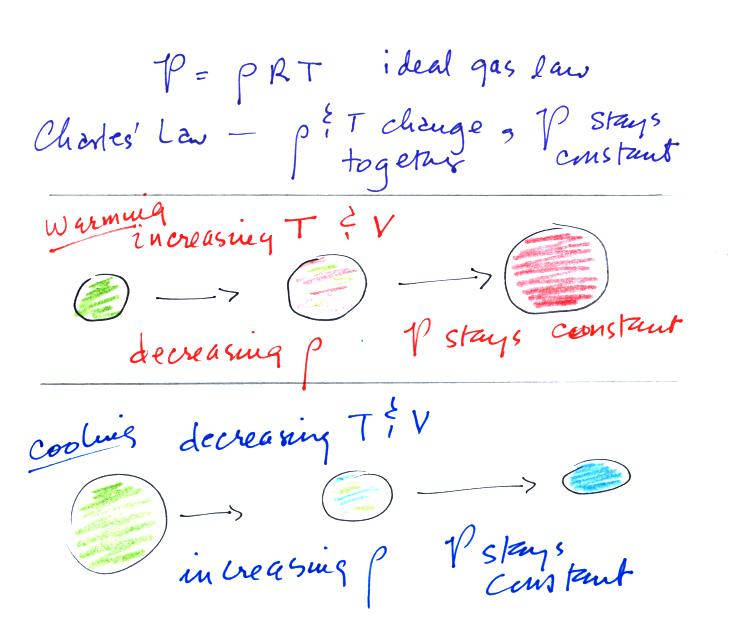

Charles' Law is a special case involving the ideal gas law.

Charles Law requires that the pressure in a volume of air remain

constant. T, V, and density can change but they must do so in a

way that keeps P constant. This is what happens in the

atmosphere. A volume of air is free to expand or shrink. It

does so to keep the pressure inside the air volume constant (the

pressure inside the volume is staying equal to the pressure of the air

outside the volume).

Read through the explanation on p.

52 in the photocopied

Classnotes. In the atmosphere a parcel (balloon) of air will

always try to keep its pressure the same as the pressure of the

surrounding air. If they aren't equal the parcel will either

expand or shrink until they are again equal.

If you warm air it will expand and density will decrease until the

pressure inside and outside the parcel are equal.

If you cool air the parcel will shrink and the density will increase

until the pressures balance.

These two associations:

(i)

warm air = low

density air

(ii) cold air = high density air

are important and will come up a

lot during the remainder of the

semester.

Click here

if you

would like a little

more detailed, more step-by-step,

explanation of Charles Law. Here's a visual summary

of Charles' Law (the

following

figure wasn't shown in class)

If you warm a parcel of air the

volume will increase and the density will decrease. Pressure

inside the parcel remains constant. If you cool the parcel of air

it's volume decreases and its density increases. Pressure inside

the parcel remains constant.

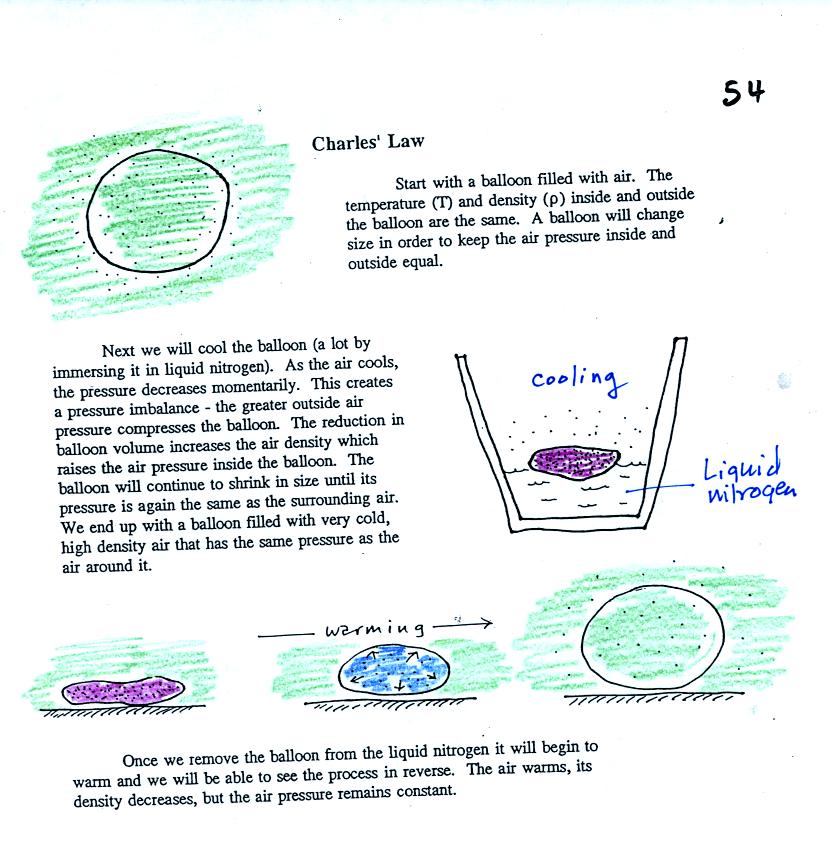

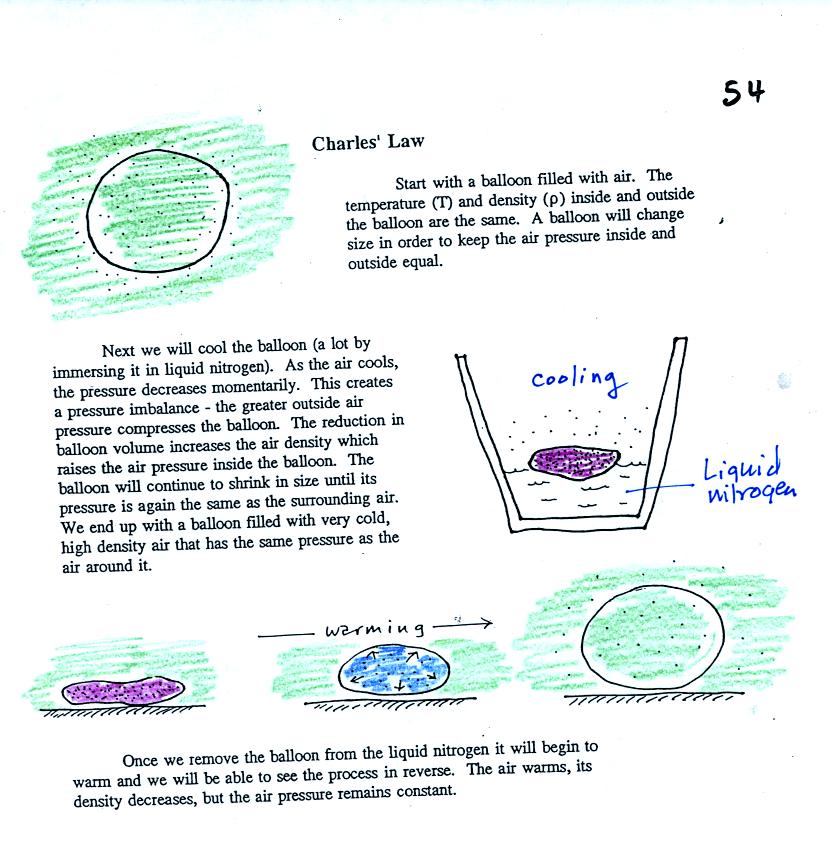

Charles

Law can be demonstrated by dipping a balloon in

liquid

nitrogen. You'll find an explanation on the top of p. 54 in the

photocopied ClassNotes.

The balloon had shrunk down to

practically zero volume when

pulled from the liquid nitrogen. It was filled with cold high

density air. As

the balloon warmed the balloon expanded and the density of the air

inside

the balloon decreased. The volume and temperature kept changing

in a way that kept pressure constant. Eventually the balloon ends

up back at room temperature (unless it pops).

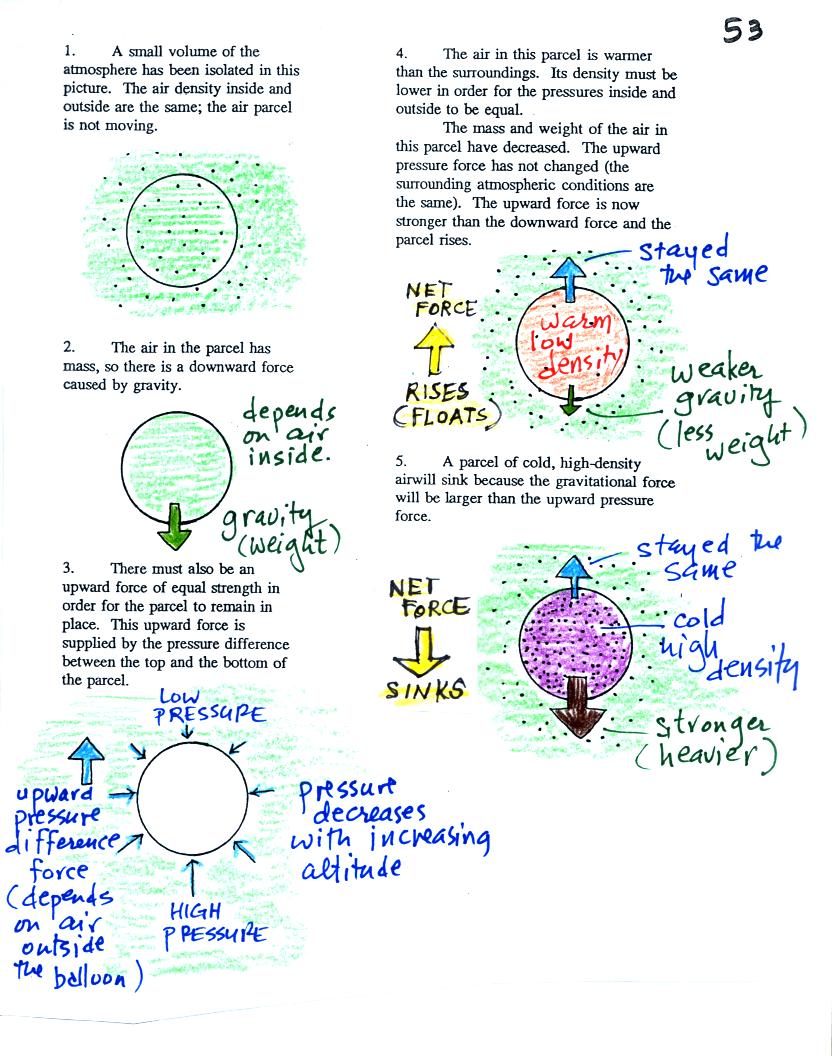

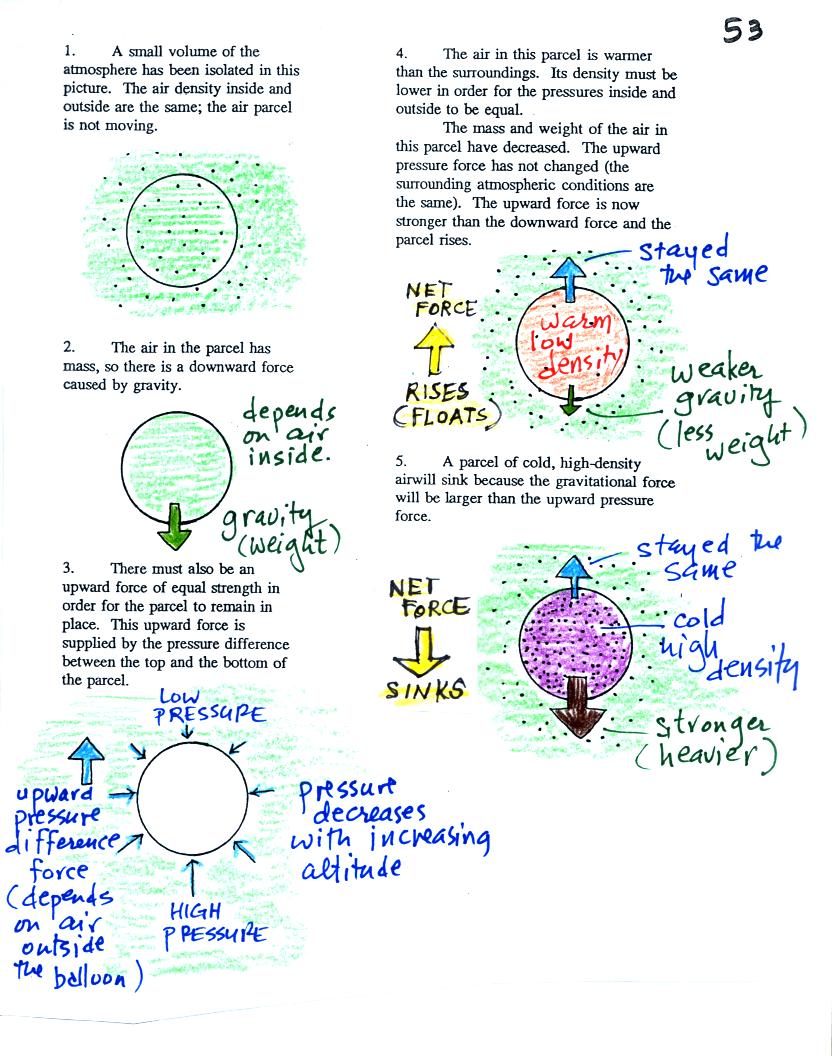

Now

finally on to step #3. It's found on p. 53 in the photocopied

ClassNotes.

Basically it comes down to is

this - there are two forces

acting on a parcel (balloon) of air in the atmosphere:

1. Gravity pulls downward. The strength of the gravity force

depends

on the mass of the air inside

the balloon.

2. There is an upward pointing pressure difference force.

This

is

caused by the air outside

(surrounding) the balloon.

When the air inside a parcel is exactly the same as the air

outside,

the two forces are equal strength and cancel out. The parcel is

neutrally bouyant and doesn't rise or sink.

If you replace the air inside the balloon with warm low density

air, it

won't weigh as much. The gravity force is weaker. The

upward

pressure difference force doesn't change (because it is determined by

the air outside the balloon which hasn't changed) and ends up stronger

than the

gravity force. The balloon will rise.

Conversely if the air inside is cold high density air, it weighs

more. Gravity is stronger than the upward pressure difference

force and the balloon sinks.

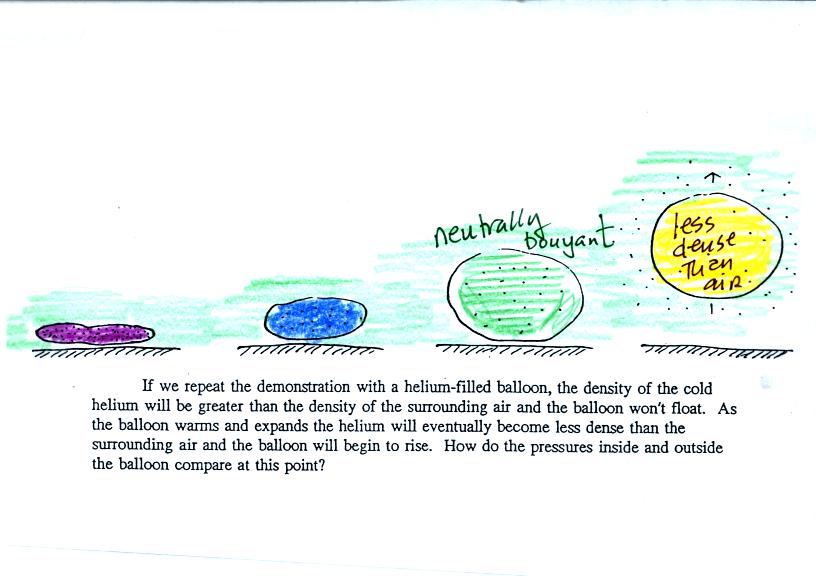

We used

balloons filled with helium instead of air (see bottom of p. 54 in

the photocopied Class

Notes). Helium is less dense than air even when the

helium has the same temperature as the surrounding air. A

helium-filled balloon doesn't need to warmed up in order to rise.

We dunked the helium-filled balloon

in some liquid nitrogen to cool

it

and to cause the density of the helium to increase. When

removed

from the liquid nitrogen the balloon didn't rise, the gas inside was

denser than the surrounding air (the purple and blue balloons in the

figure above). As the balloon warms and expands

its density decreases. The balloon at some point has the same

density as the air around it (green above) and is neutrally

bouyant. Eventually the balloon becomes less dense that the

surrounding air (yellow) and floats up to the ceiling.

Something like this happens in the

atmosphere.