During the demonstration someone mentioned that they thought the color indicator should turn red. There are lots of color pH indicators. The photo above shows some that are left over from the ATMO 171 Lab class. Some of these do turn red. The reason for the variety of indicators is that the color change takes place at different pH values.

Now that we've learned something about the composition of the atmosphere we will be learning about some of its other physical properties such as temperature, air density, and air pressure. We'll also be interested in how they change with altitude.

Two bottles, one containing mercury the other an equal volume of water, were passed around class. Even though the volumes were the same, the masses, weights, and densities were very different.

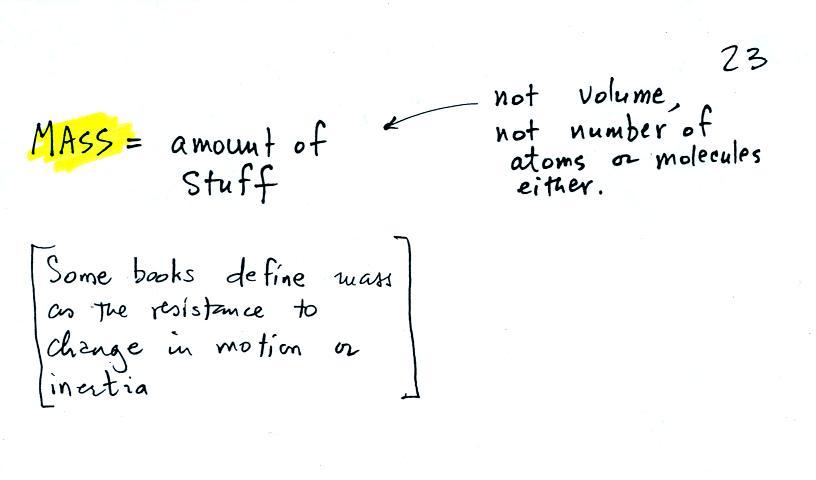

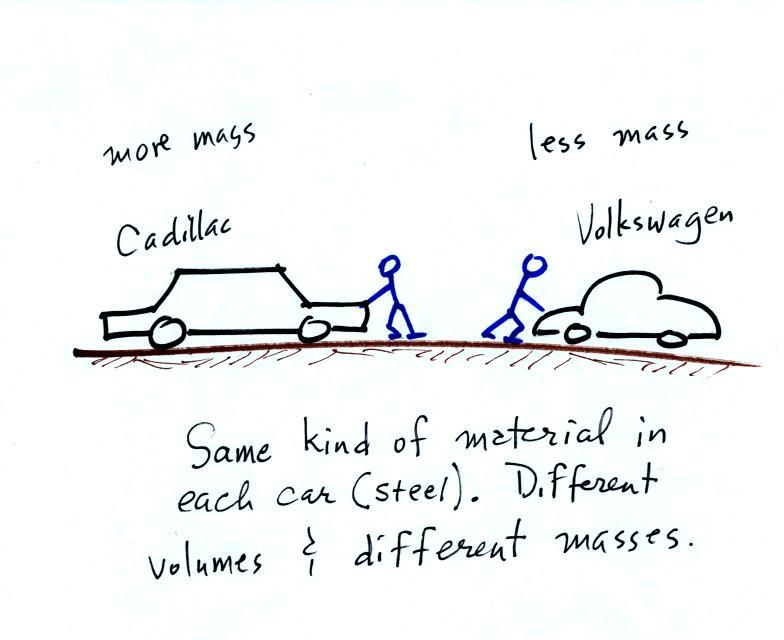

Other books will define mass as inertia or as resistance to change in motion (this comes from Newton's 2nd law of motion, we'll cover that later in the semester). The next picture illustrates both definitions.

A Cadillac and a volkswagen

have both stalled in an intersection. Both cars are made of

steel. The Cadillac is larger and has more steel, more stuff,

more mass. The Cadillac would be much harder to get moving than

the VW, it has

a larger inertia (it would also be harder to slow down and stop once it

is

moving).

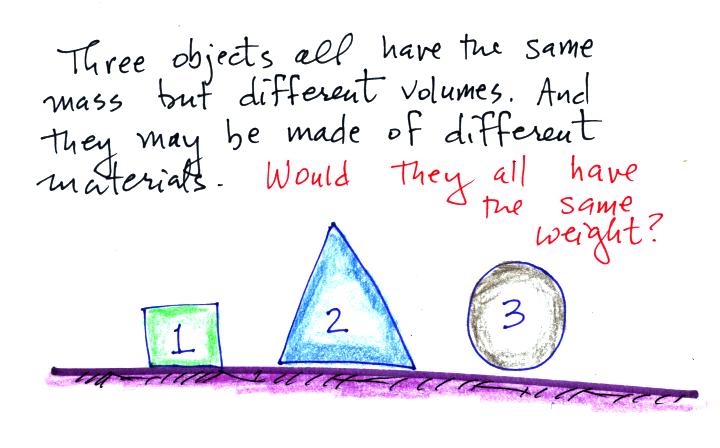

Here are a couple of questions that I asked in class.

We assume that all three objects are here on the earth.

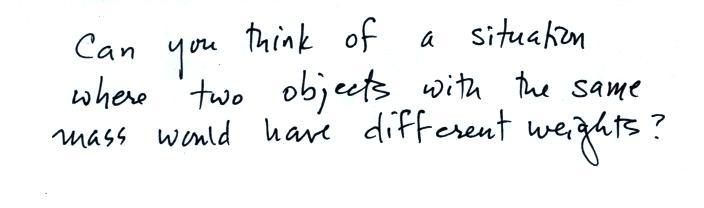

To determine the weight you multiply the mass by the gravitational acceleration. Since all three objects have the same mass and g is a constant you get the same weight for each object. That's why we use mass and weight interchangeably on the earth. Here was a follow up question:

Here's a little more information (not covered in class) about what determines the value of the gravitational acceleration (Newton's Law of Universal Gravitation).

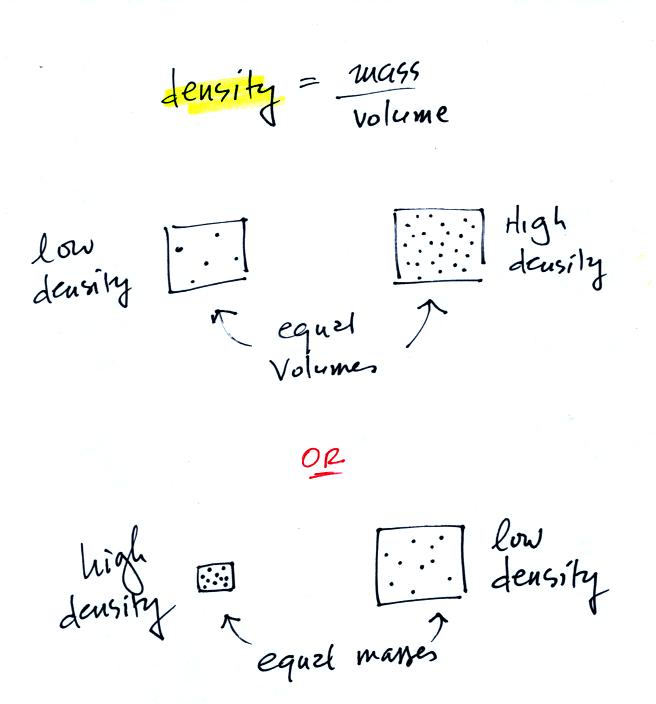

Density is the next term we need to look at.

In

the first example there is more mass (more dots, which symbolize air

molecules) in the right box than

in the left box. Since the two volumes are equal the box at right

has higher density. Equal masses are squeezed into different

volumes in the bottom example. The box with smaller volume has

higher density.

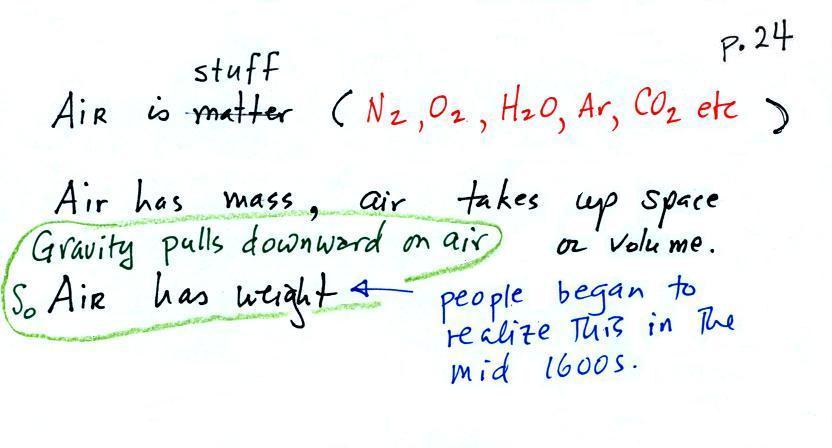

The air that surrounds the earth has mass. Gravity pulls downward on the atmosphere giving it weight. Galileo conducted (in the 1600s) a simple experiment to prove that air has weight. The experiment wasn't mentioned in class.

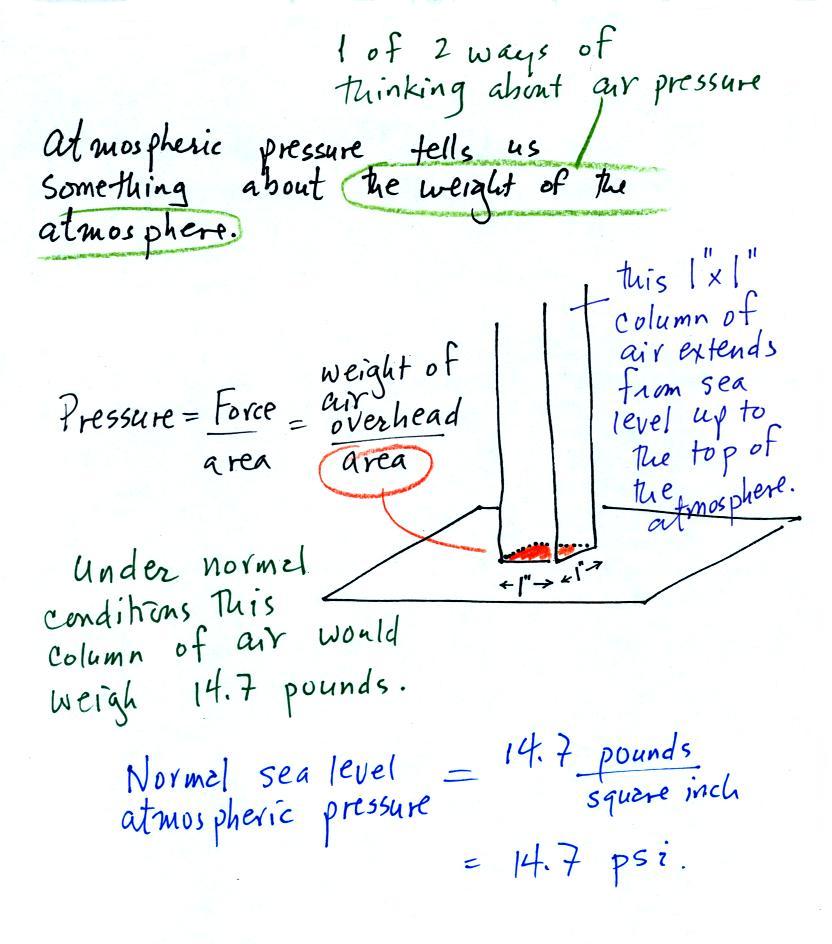

Atmospheric pressure depends on, is determined by, the weight of the air overhead. This is one way, a sort of large scale representation, of understanding air pressure.

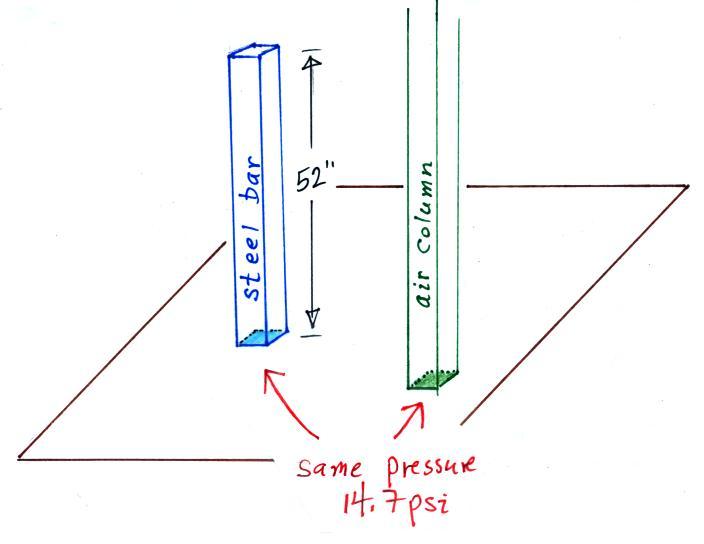

Under normal conditions a 1 inch by 1 inch column of air stretching from sea level to the top of the atmosphere will weigh 14.7 pounds. Normal atmospheric pressure at sea level is 14.7 pounds per square inch (psi, the units you use when you fill up your car or bike tires with air).

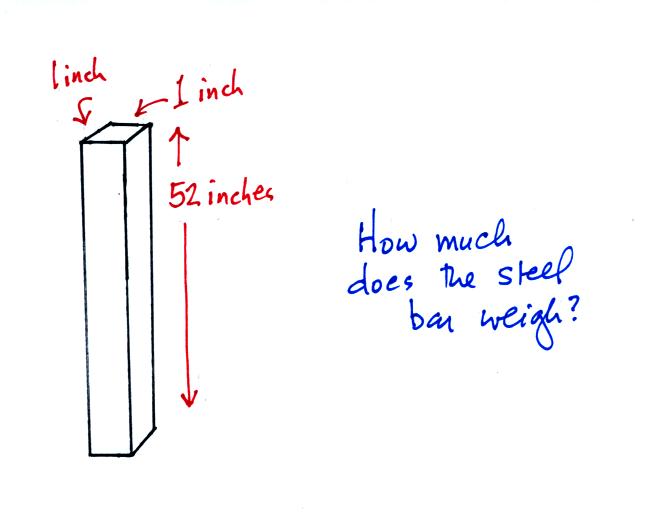

The iron bar sketched below was passed around class today. You were supposed to estimate it's weight.

It also weighs 14.7 pounds. When you stand the bar on end, the pressure at the bottom would be 14.7 psi.

So the weight of a 1" x 1" steel bar 52 inches long is the same as a 1" x 1" column of air that extends from sea level to the top of the atmosphere 100 or 200 miles (or more) high. The pressure at the bottom of both would be 14.7 psi.

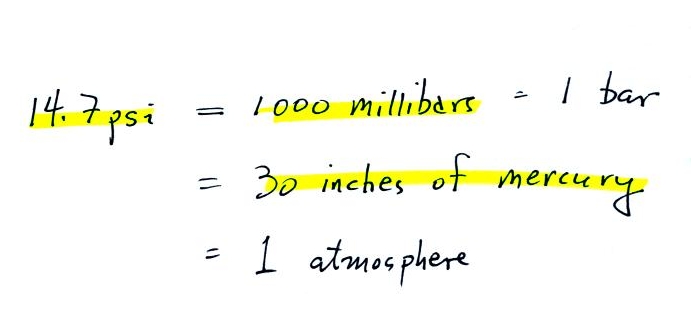

Psi are perfectly good pressure units, but they aren't the ones that most meteorologists used.

Typical sea level pressure is 14.7 psi or about 1000 millibars (the units used by meterologists and the units that we will use in this class most of the time) or about 30 inches of mercury (refers to the reading on a mercury barometer, we'll cover mercury barometers on Friday, they're used to measure pressure). Milli means 1/1000 th. So 1000 millibars is the same as 1 bar. You sometimes see typical sea level pressure written as 1 atmosphere.

Mercury (13.6 grams/cm3) is denser than steel ( about 7.9 grams/cm3 ) so it would only take about a 30 inch tall column of mercury to produce atmospheric presure.

You never know whether something you learn in NATS 101 (or ATMO 170A1 as it's now called) will turn up. I lived and worked for a short time in France (a very enjoyable and interesting period in my life). Here's a picture of a car I owned when I was there (this one is in mint condition, mine was in far worse shape)

It's a Peugeot 404. After buying it I took it to the service station to fill it with gas and to check the air pressure in the tires. I was a little confused by the air compressor though, the scale only ran from 0 to 3. I'm used to putting 30 psi or so in my car tires (about 90 psi in my bike tires). After staring at the scale for a while I finally realized the numbers were pressures in "bars" not "psi". Since 14.7 psi is equivalent to 1 bar, 30 psi would be about 2 bars. So I filled up all the tires and carefully drove off (one thing I learned you have to watch out for in France is the "Priority to the right" rule).

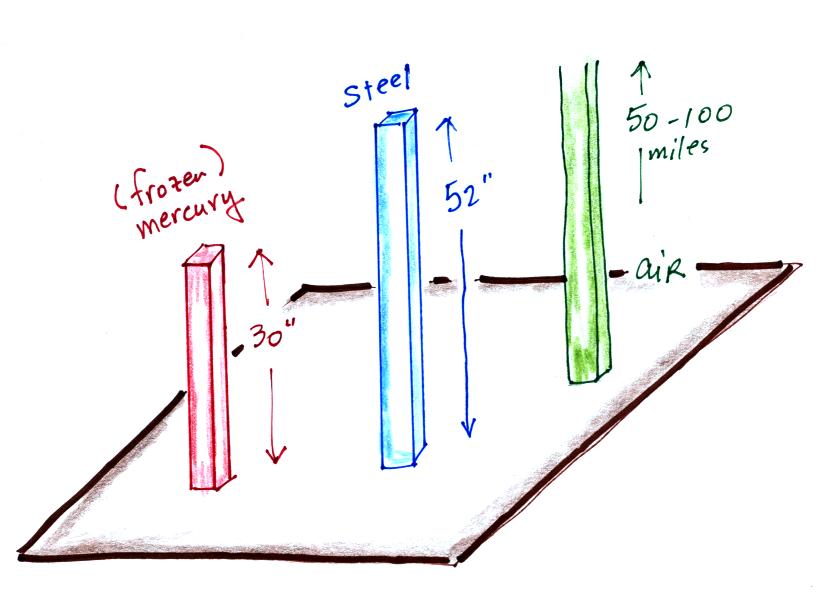

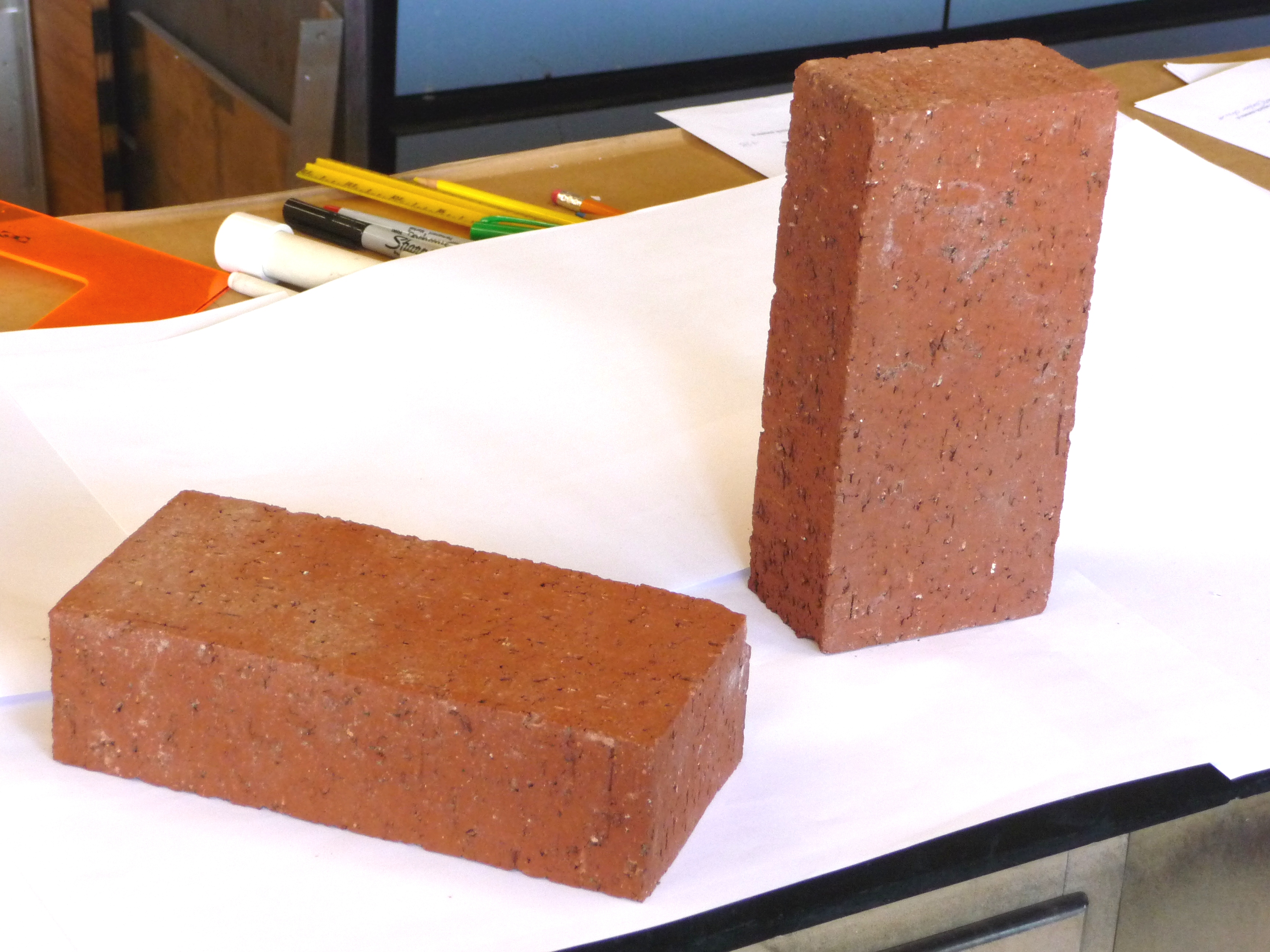

You can learn a lot about pressure from bricks.

For example the photo below (taken in my messy office) shows two of the bricks from class. One is sitting flat, the other is sitting on its end. Each brick weighs about 5 pounds. Would the pressure at the base of each brick be the same or different in this kind of situation?

Pressure is determined by (depends on) weight so you might think the pressures would be equal. But pressure is weight divided by area. In this case the weights are the same but the areas are different. In the situation at left the 5 pounds must be divided by an area of about 4 inches by 8 inches = 32 inches. That works out to be about 0.15 psi. In the other case the 5 pounds should be divided by a smaller area, 4 inches by 2 inches = 8 inches. That's a pressure of 0.6 psi, 4 times higher. Notice also these pressures are much less the 14.7 psi sea level atmospheric pressure.

The main reason I brought the bricks was so that you could understand what happens to pressure with increasing altitude. Here's a drawing of the 5 bricks stacked on top of each other.

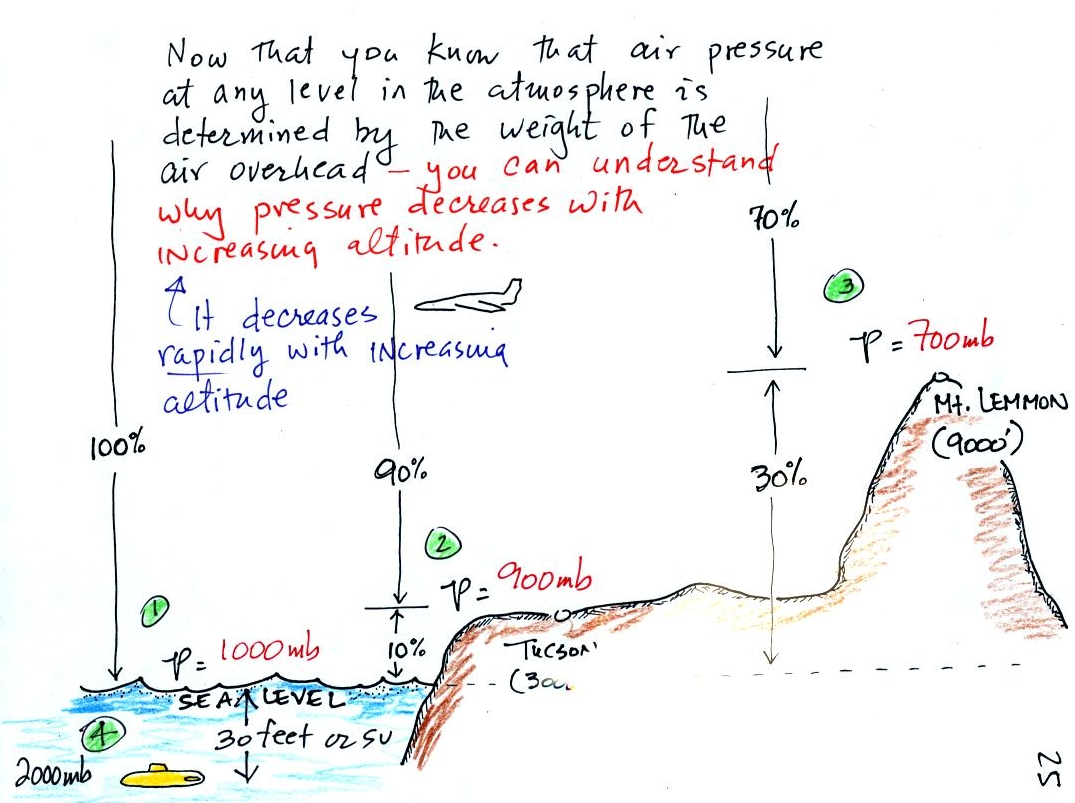

The atmosphere is really no different. Pressure at any level is determined by the weight of the air still overhead. Pressure decreases with increasing altitude because there is less and less air remaining overhead. The figure below is a more carefully drawn version of what was done in class.

At sea level altitude, at Point 1, the pressure is normally about 1000 mb. That is determined by the weight of all (100%) of the air in the atmosphere.

Some parts of Tucson, at Point 2, are 3000 feet above sea level (most of central Tucson is a little lower than that around 2500 feet). At 3000 ft. about 10% of the air is below, 90% is still overhead. It is the weight of the 90% that is still above that determines the atmospheric pressure in Tucson. If 100% of the atmosphere produces a pressure of 1000 mb, then 90% will produce a pressure of 900 mb.

Pressure is typically about 700 mb at the summit of Mt. Lemmon (9000 ft. altitude at Point 3) and 70% of the atmosphere is overhead..

Pressure decreases rapidly with increasing altitude. We will find that pressure changes more slowly if you move horizontally. Pressure changes about 1 mb for every 10 meters of elevation change. Pressure changes much more slowly normally if you move horizontally: about 1 mb in 100 km. Still the small horizontal changes are what cause the wind to blow and what cause storms to form.

Point 4 shows a submarine at a depth of about 30 ft. or so. The pressure there is determined by the weight of the air and the weight of the water overhead. Water is much denser and much heavier than air. At 30 ft., the pressure is already twice what it would be at the surface of the ocean (2000 mb instead of 1000 mb).

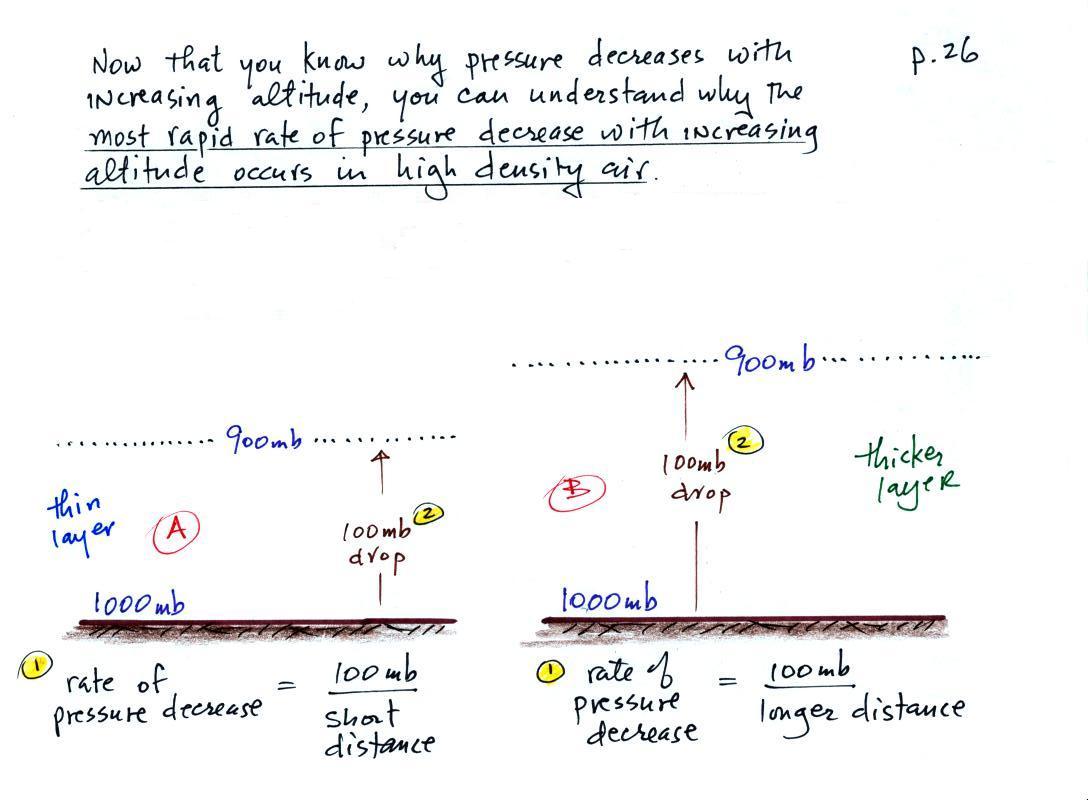

This next figure explains the rate of pressure change as you move or down in the atmosphere depends on air density. In particular air pressure will decrease more quickly when you move upward through high density air than if you move upward through low density air.

1. The rate of pressure decrease with increasing altitude is greatest in Layer A. To determine the rate of pressure decrease you divide the pressure change (100 mb for both layers) by the distance over which that change occurs. The 100 mb change takes place in a shorter distance in Layer A than in Layer B. Layer A has the highest rate of pressure decrease with increasing altitude.

2. There is a 100 mb drop in pressure in both air layers. Pressure depends on the weight of the air overhead. As you move upward in the atmosphere you remove air that was above and put it below you. If the pressure change is the same in both layers, you must have moved the same weight of air in both cases. Both layers must have the same amount (the same mass) of air.

3. Density is mass divided by volume. The air in the Layer A is denser than the air in Layer B. The same amount (mass) of air is squeezed into a thinner layer, a smaller volume, in the left layer. This results in higher density air.

So both the most rapid rate of pressure decrease with altitude and the densest air are found in Layer A.

The fact that the rate of pressure decrease with increasing altitude depends on air density is a fairly subtle but important concept. This concept will come up 2 or 3 more times later in the semester. For example, we will need this concept to explain why hurricanes can intensify and get as strong as they do.