Something else to notice in the figure. Storm systems

in the tropics (0 to 30 degrees latitude) generally move from

east to west in both hemispheres. And that's something

to watch out for. We get used to things switching

directions when we move from one hemisphere to the

other. Some things do, others don't.

At middle latitudes (30 to 60 degrees), storms move in the

other direction, from west to east. To understand why

this is true we need to learn something about the earth's

global scale pressure and wind patterns. We'll get to

that next week also.

We'll be able to learn most of what we need to know about

surface and upper level winds in 10 easy steps (though I've

broken several of the steps into smaller parts)

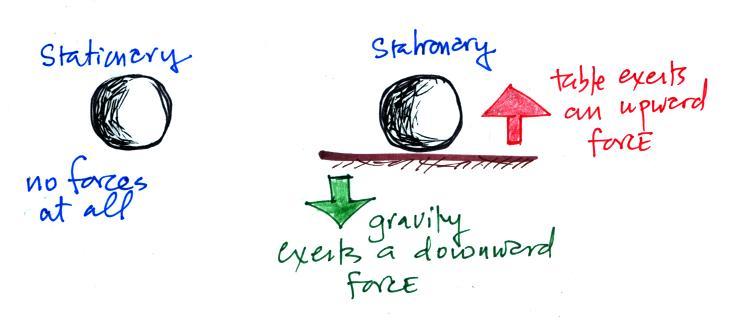

Step #1

Here's a slightly different version of p. 122a in the

ClassNotes.

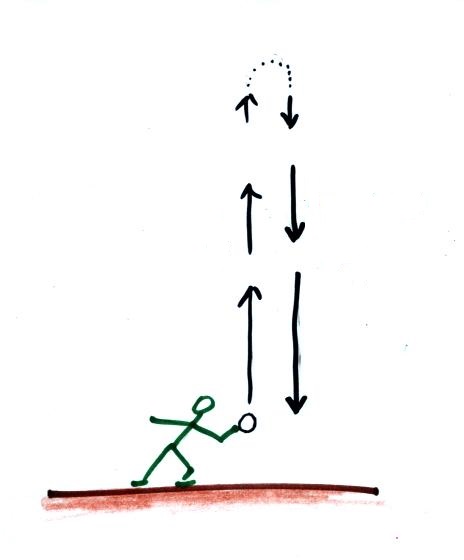

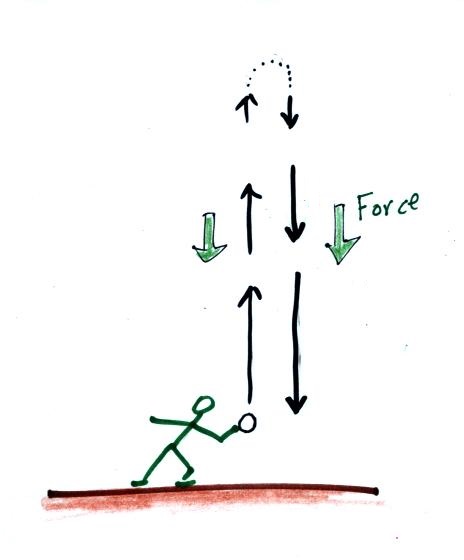

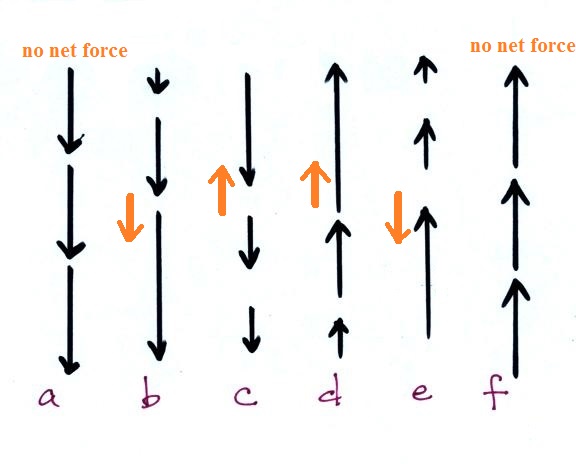

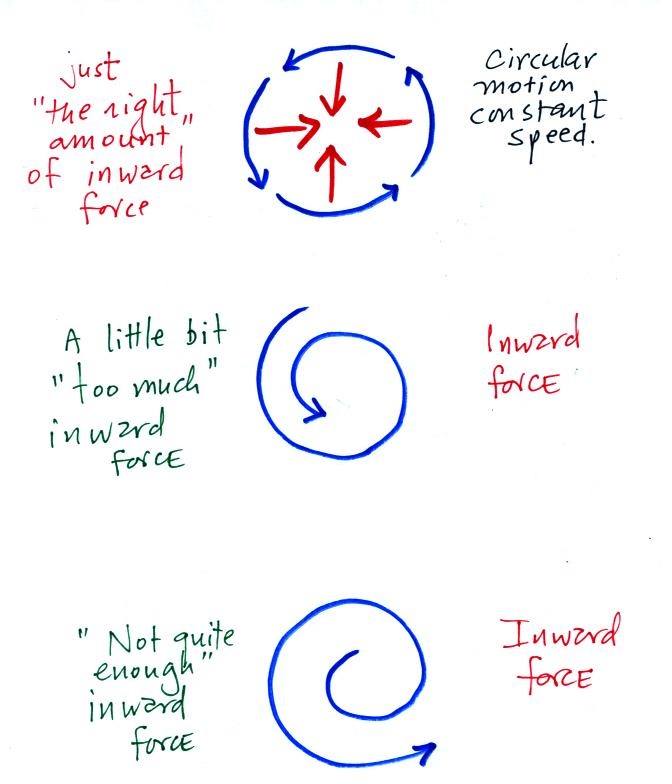

What about these three examples. Is there a

net inward or outward force in each case. You should

now know that there is a net inward force in the 1st example

because that's what we've just been covering. What

about the next two. The 3rd example usually causes

people the most trouble. You'll find the answer to

this question at the end of today's notes.

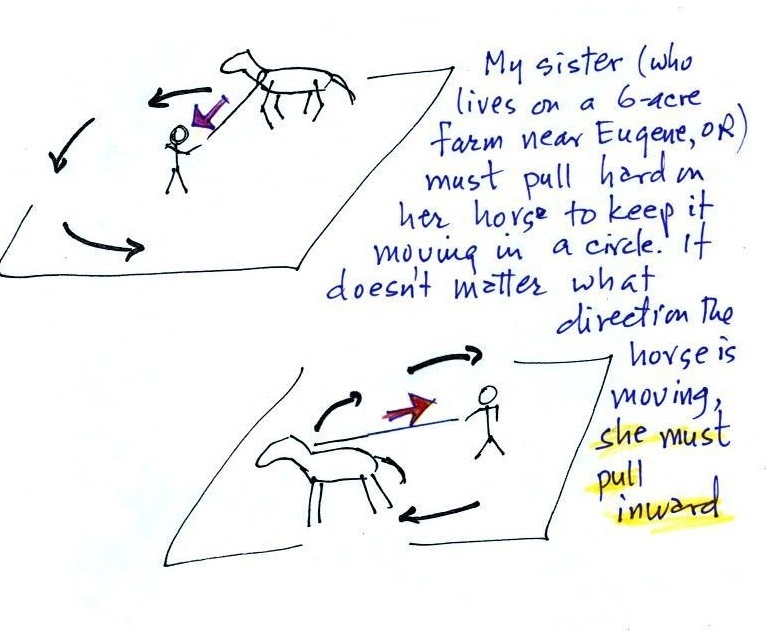

Now

we'll start to look at the forces that cause

the wind to blow.

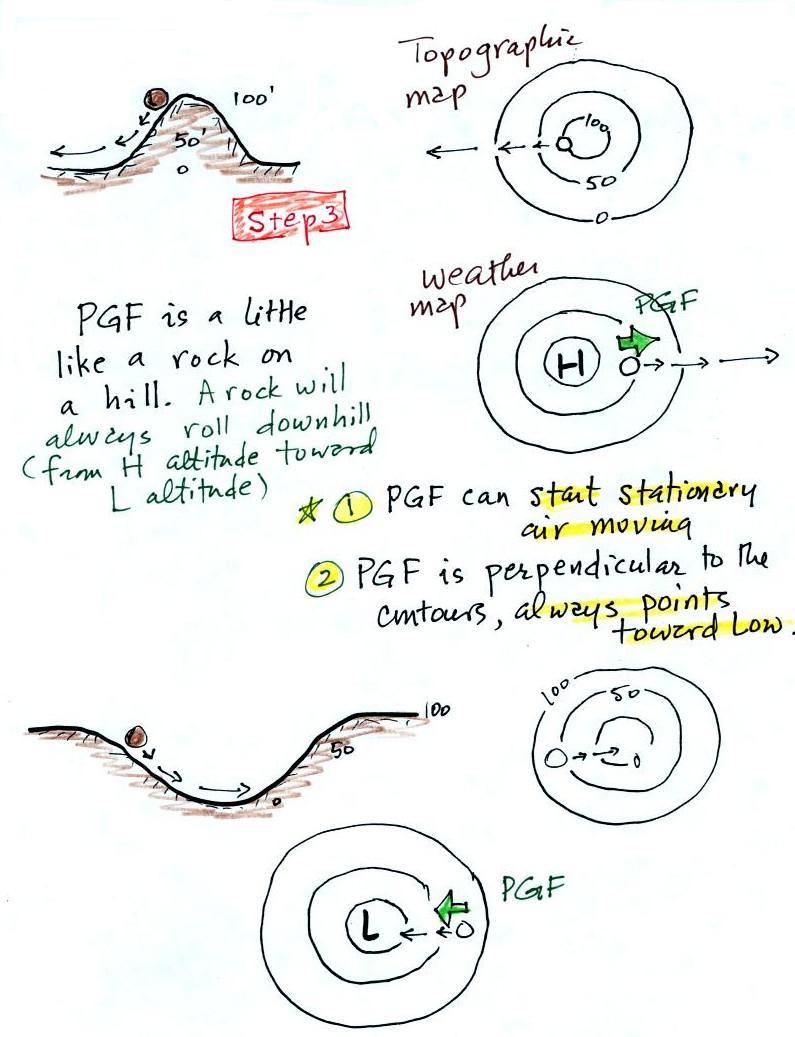

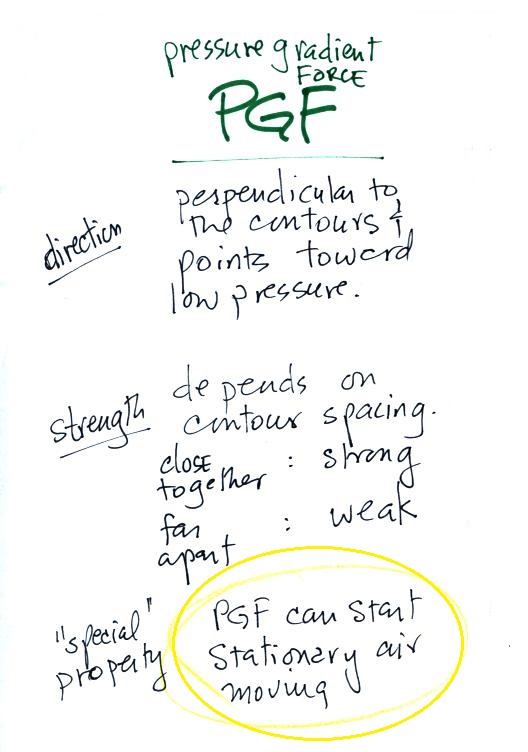

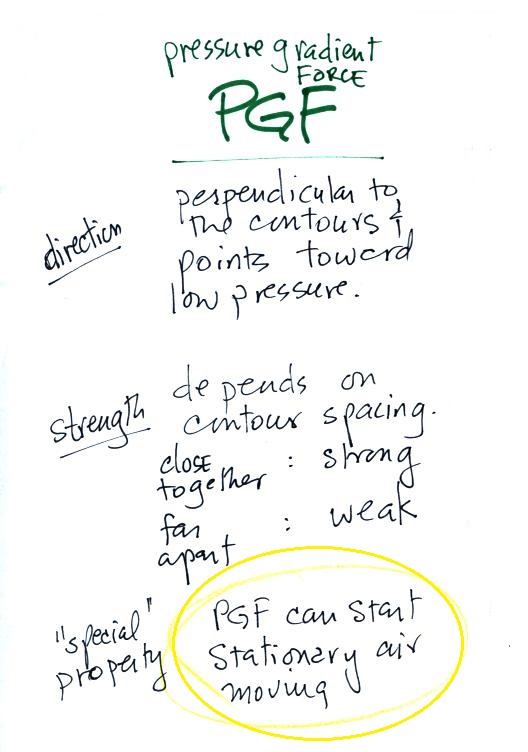

Step #3 Pressure

Gradient Force (PGF)

I didn't

actually show this figure in class (it's

on p. 123a in the ClassNotes)

Isobars on a weather map are very much like height

contours on a topographic map. A center of low pressure on

a weather map is analogous to a circular valley on a topographic

map (high pressure on a weather chart is like a circular hill).

The PGF always points in a direction that is perpendicular to

the contour lines and toward low pressure. The PGF can

start stationary air moving. The air will always start

moving toward low pressure. Air moving inward toward low

pressure or outward away from high pressure is similar to a rock

rolling downhill into the center of a valley or downhill away

from the summit of a hill.

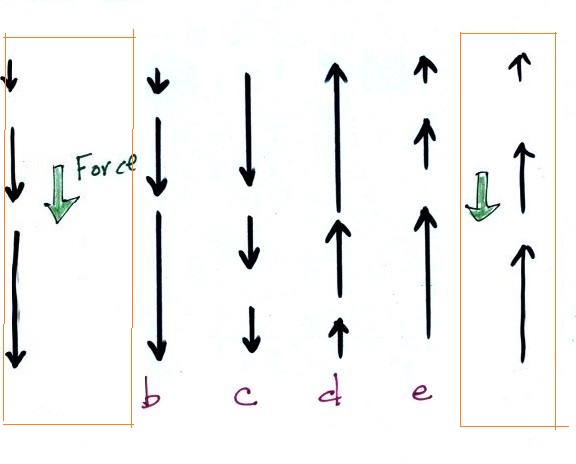

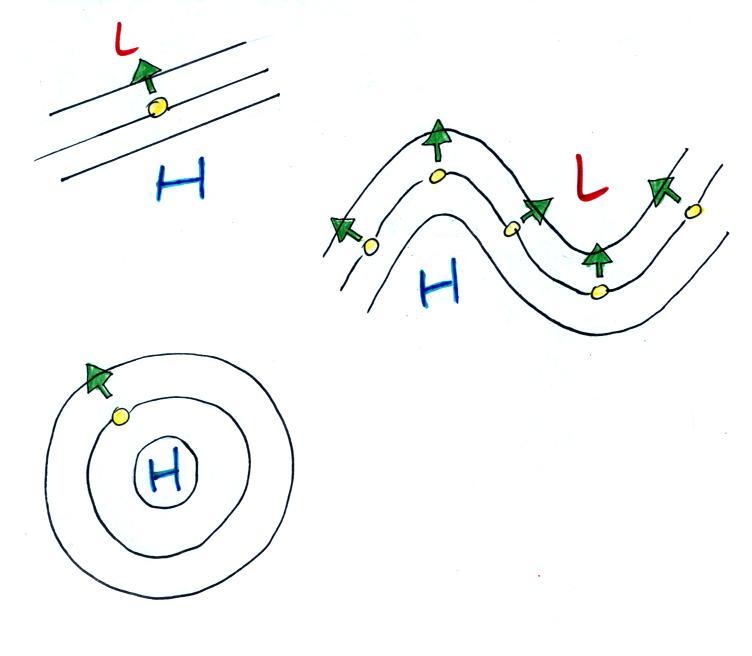

Use the following figure to test yourself. With an arrow

draw the direction of the PGF at each of the points in the

figure. You'll find the answers at the end of today's

notes.

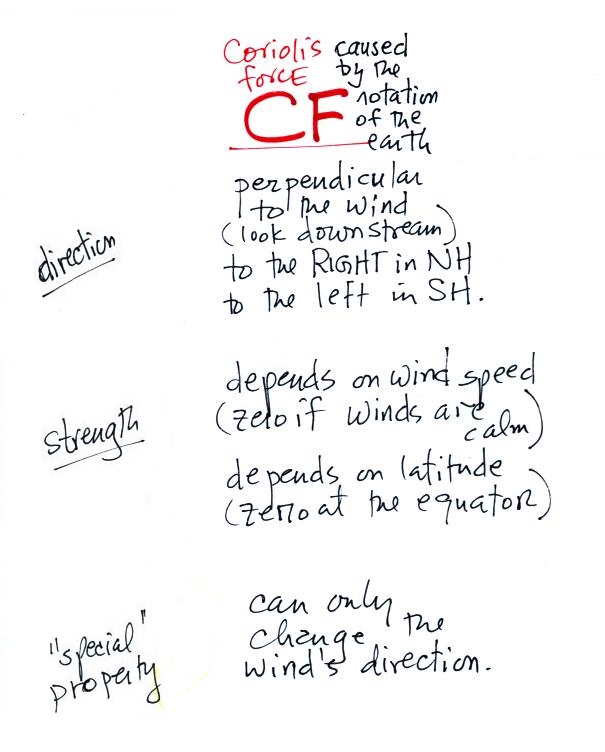

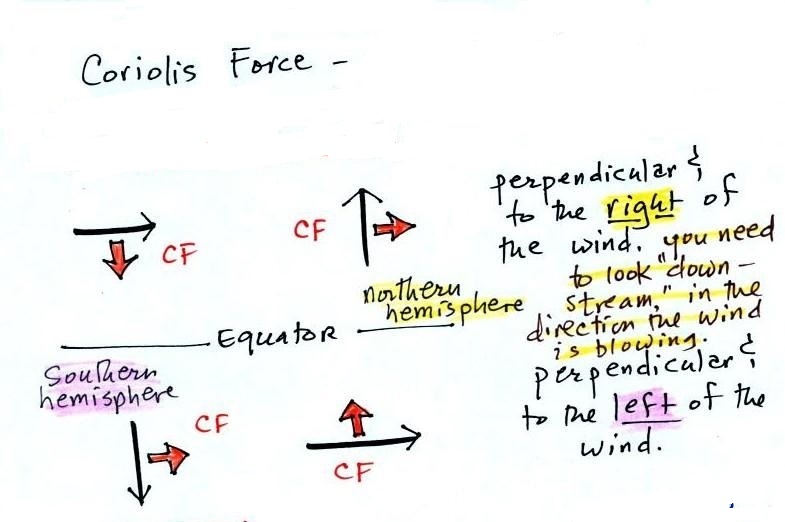

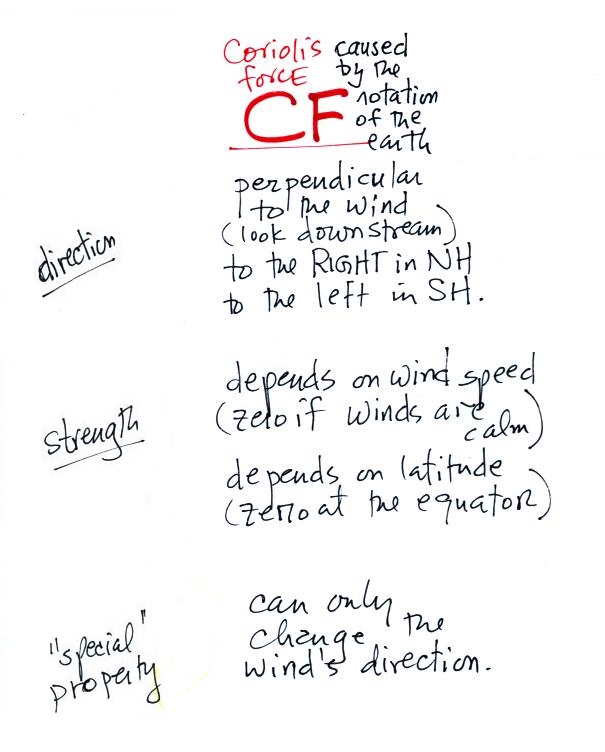

Step #4 - Coriolis force (CF)

The rules for the CF are shown below.

The top of p. in the ClassNotes has several examples showing

the direction of the CF. You can use them to check and

make sure you understand how to apply the direction rule

above.

The Coriolis force is caused by the rotation of the

earth. We'll learn more about the Coriolis force next

week. The CF points perpendicular to the wind and is to

the right or left depending on hemisphere. Be sure you

are looking in the direction the wind is blowing, looking

downstream when determining the direction of the CF.

The CF can only change the wind's direction. It can't

cause the wind to speed up or slow down.

There isn't any Coriolis force when the wind is calm.

Coriolis force is zero at the equation because that's where

the CF changes direction. Hurricanes don't form at the

equator because there is no Coriolis force there.

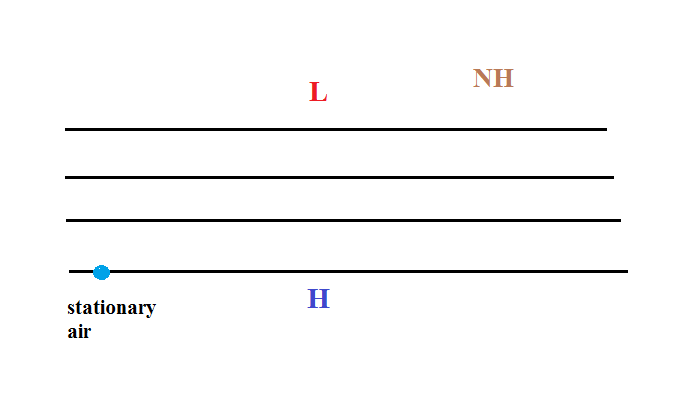

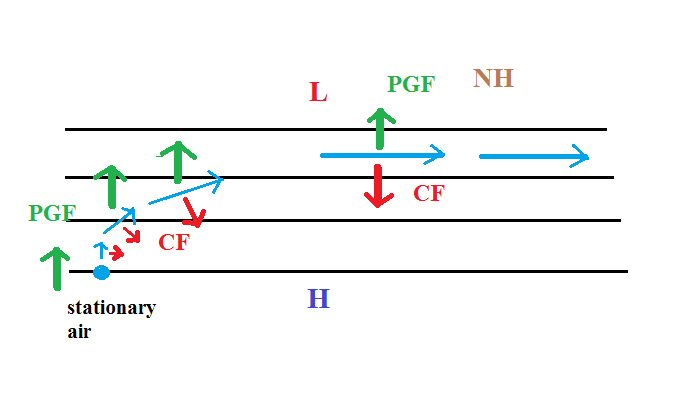

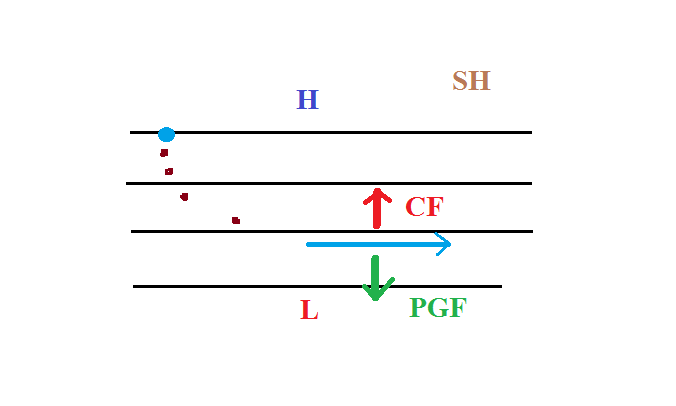

Time now to begin to apply what we've learned so far.

We'll consider the simplest possible situation - upper

level winds with straight contours. We'll do a

Northern Hemisphere (NH) example.

We start with some stationary air in

the lower left corner of the picture. Low pressure

is at the top and high pressure at the bottom of the

picture.

The PGF can start stationary air moving. The PGF

will point toward the top of the picture (perpendicular

to the contours and toward the low pressure at the

top). There won't be any Coriolis force when the

air is stationary.

Once the wind starts to blow (blue

line above) the CF will appear. The CF will be

weak at first because the wind speed is low but the CF

will begin to turn the wind to the right. As the

wind picks up speed the CF will increase in

strength. Eventually the wind will be blowing

parallel to the contours from left to right. The

PGF and CF point in opposite directions and are of equal

strength. The net force is zero and the wind will

continue to blow to the right in a straight line at

constant speed.

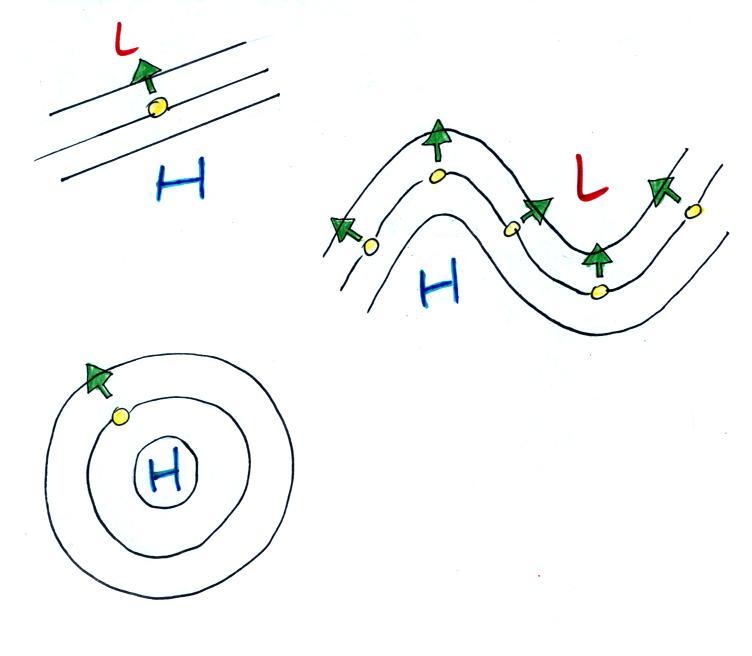

Here's a simpler less cluttered way of depicting what we

have just figured out.

The dots show the direction of the initial motion.

That will always be toward low pressure. Then you

look in the direction the wind starts to blow and look

to see if the wind turns right or left. It turned

right in this case. That's the effect of the

Coriolis force and means this is a northern hemisphere

map.

Here's one last example to test your understanding.

The direction of the initial motion is shown with

dots. Where is the high and low pressure in this

case? Is this a NH or SH chart. You'll find

the completed map at the end of today's notes.

Here are the answers to a couple of question embedded in

the notes.

A net inward force is needed in all

three cases. The thing that changes is the

strength of the inward force.

This figure shows the directions of the

PGF at each of the highlighted points. The

mistake many people make is to draw the arrow pointing

straight toward the L.

But the PGF arrow must also always be perpendicular to the

contour lines.