Friday, Apr. 1, 2016

Copenhagen Philharmonic Symphony "Ravel's

Bolero" (4:52), Grieg's "Peer Gynt"

(2:16), Naturally 7 performing Phil Collin's "In the Air

Tonight" (5:12)

Precipitation producing processes

The last topic we will cover before

next week's quiz is precipitation formation and types of

precipitation.

Only two of the 10 main cloud types (nimbostratus and

cumulonimbus) are able to produce significant amounts of

precipitation and produce precipitation that can survive

the fall from cloud to ground without evaporating. Why

is that?

Before we get into the details you will notice I underlined

significant amounts in the sentence above. That is because

you will sometimes see streamers of precipitation falling from

some of the other cloud types, clouds that you would not have

thought capable of producing precipitation. There were a few

raindrops falling from stratocumulus clouds after the 11 am class

last Wednesday. I've included some other examples below

|

|

Streamers of snow falling from either

mid or high altitude clouds at sunset. (source

of this image)

|

Snow falling from high altitude cirrus

uncinus clouds, photographed in Catalina, Arizona, I

believe. (source

of this image)

|

|

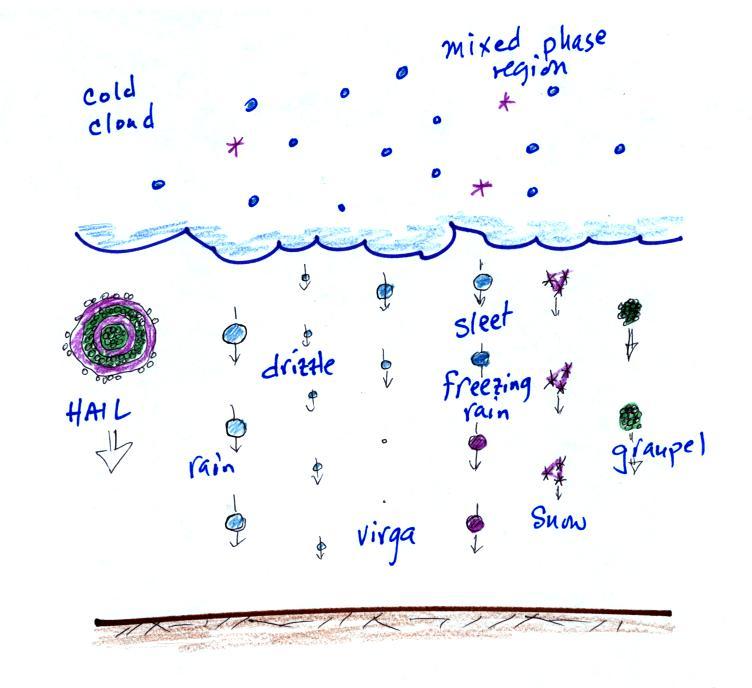

Precipitation like this that evaporates (or sublimes) before

reaching the ground is called virga. The rain that was

coming from low altitude clouds on Wednesday this week survived

the fall to the ground, but it was very light. There wasn't

enough to even dampen the ground.

Why is it so hard for clouds to make precipitation?

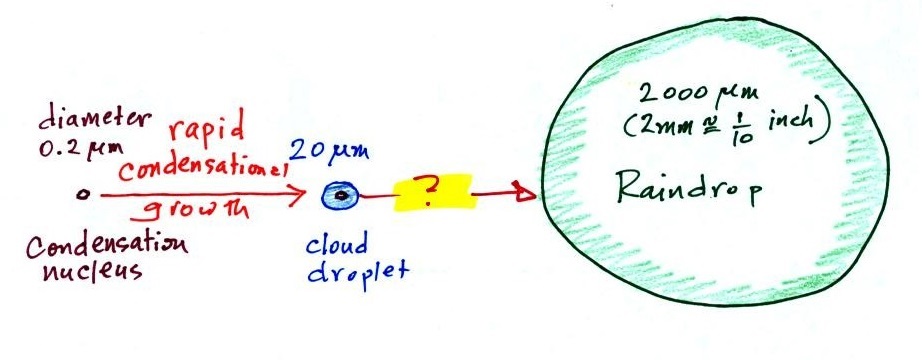

This figure shows typical sizes of cloud condensation

nuclei (CCN), cloud droplets, and raindrops (a human hair

is about 50 μm thick for comparison).

As we saw in the cloud in a bottle demonstration it is relatively

easy to make cloud droplets. You cool moist air to the dew

point and raise the RH to 100%. Water vapor condenses pretty

much instantaneously onto a cloud condensation nucleus to form a

cloud droplet. It would take much longer (a day or more) for

condensation to turn a cloud droplet into a raindrop. You

must know from personal experience that once a cloud forms you

don't have to wait that long for precipitation to begin to fall.

Part of the problem is that it takes quite a few 20 μm

diameter cloud droplets to make one 2000 μm

diameter raindrop. A raindrop is about 100 times bigger

across than a cloud droplet. How many droplets are needed to

make a raindrop? Before answering that question we will look

at a cube (rather than a sphere).

How many sugar cubes would

you need to make a box that is 4 sugar cubes on a side?

It

would take 16 sugar cubes to make each layer and

there are 4 layers. So you'd need 64 sugar

cubes. Volume is length x width x height.

The raindrop is 100 times wider, 100 times

bigger from front to back, and 100 times taller than

the cloud droplet. The raindrop has a volume

that is 100 x 100 x 100 = 1,000,000 (one million)

times larger than the volume of the cloud

droplets. It takes about a million

cloud droplets to make one average size raindrop.

Precipitation-producing

processes

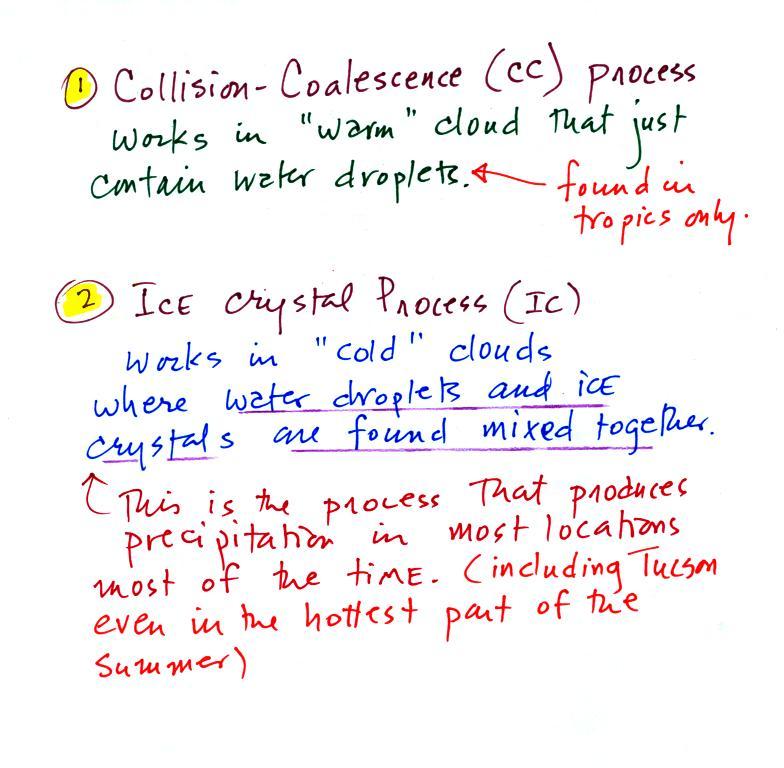

Fortunately there are two processes capable of quickly turning

small cloud droplets into much larger precipitation particles

in a cloud.

The collision coalescence process works in clouds that are

composed of water droplets only. This is often called the

"warm rain" process. Clouds like this are only found in

the tropics. We'll see that this is a pretty easy process

to understand.

This process will only produce rain, drizzle, and something

called virga (rain that evaporates before reaching the

ground). Because the clouds are warm and warm air can

potentially contain more water vapor than cooler air, the

collision-coalescence process can produce very large amounts of

rain.

The ice crystal process produces precipitation everywhere

else. This is the process that makes rain in Tucson, even on

the hottest day in the summer (summer thunderstorm clouds are tall

and reach into cold parts of the atmosphere, well below

freezing). Hail and graupel

often fall from these storms; proof that the precipitation started

out as an ice particle). Thunderstorms also produce

lightning and later in the semester we will find that ice is needed to make the electrical charge

that leads to lightning.

There is one part of this process that is a

little harder to understand, but look at the variety of

different kinds of precipitation particles (rain, snow,

hail, sleet, graupel, etc) that can result.

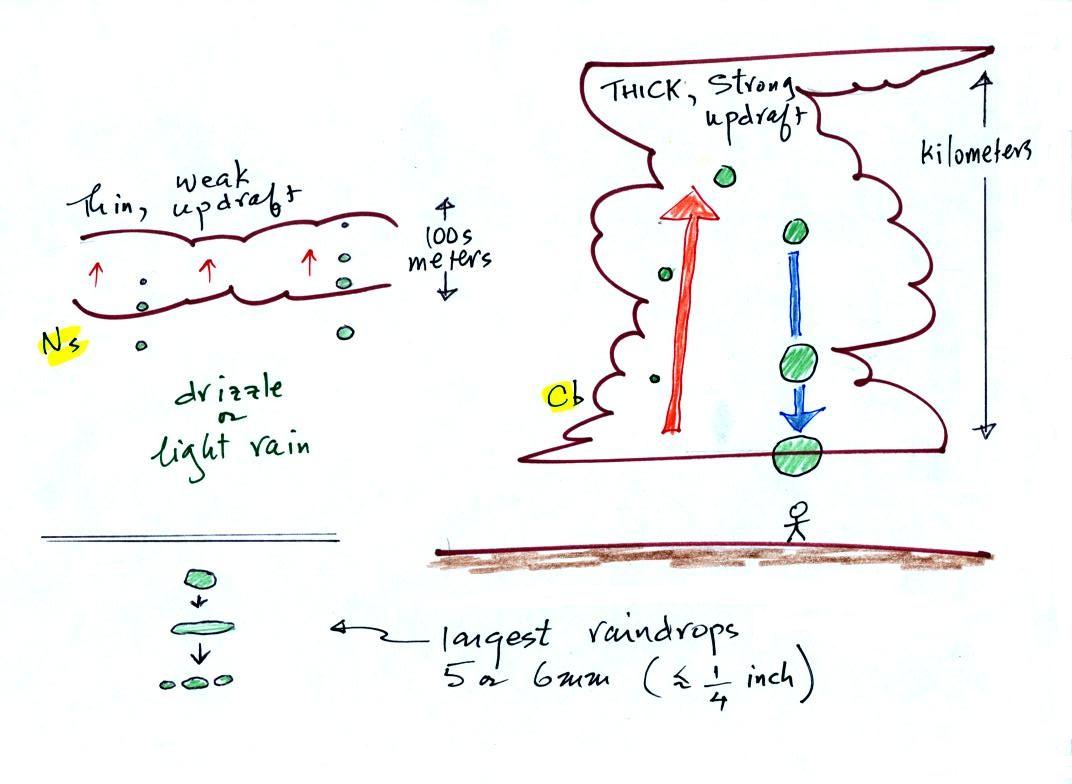

Here's how the collision coalescence process works. The

picture below shows what you might see if you looked

inside a warm cloud with just water droplets:

The collision coalescence

process works in a cloud filled with cloud droplets of

different sizes, that's critical. The

larger droplets fall faster than the small droplets. A

larger-than-average cloud droplet will overtake and collide with

smaller slower moving ones.

The bigger droplets

fall faster than the slower ones. They collide and

stick together (coalesce). The big drops gets even

bigger, fall faster, and collide more often with the smaller

droplets. This is an accelerating growth process -

think of a growing ball of snow as it rolls down a

snow-covered hill and picks up snow, grows, and starts to

roll faster and faster; or think of an avalanche

that gets bigger and moves faster as it travels downslope.

A larger than average cloud droplet can very quickly grow

to raindrop size.

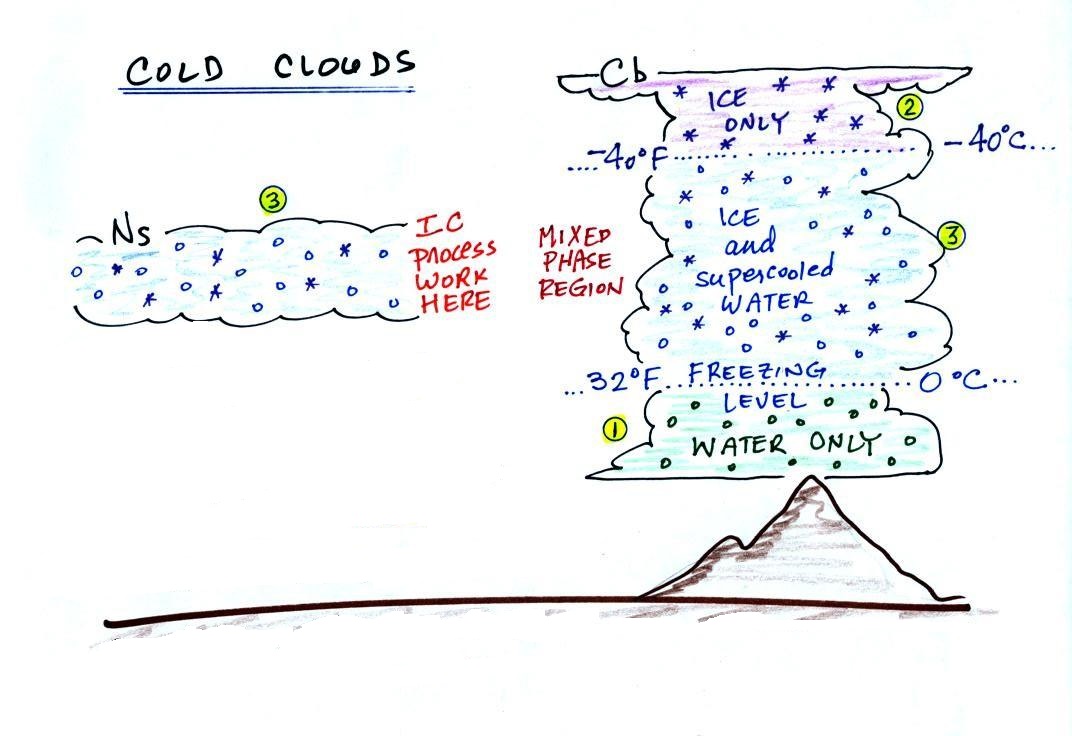

The figure shows the two precipitation producing clouds:

nimbostratus (Ns) and cumulonimbus (Cb). Ns

clouds are thinner and have weaker updrafts than Cb clouds.

The largest raindrops fall from Cb clouds because the droplets

spend more time in the cloud growing. In a Cb cloud raindrops can

grow while being carried upward by the updraft and also when

falling in the downdraft.

Raindrops grow up to about 1/4 inch in diameter. When

drops get larger than that, wind resistance flattens out the drop

as it falls toward the ground. The drop begins to "flop" or

"wobble" around and breaks apart into several smaller

droplets. Solid precipitation particles such as hail can get

much larger (an inch or two or three in diameter).

And actually my sketch at lower left above isn't quite accurate

as this video of the breakup of a

5 mm diameter drop of water shows.

The ice crystal process works in most locations most of the

time. Before we can look at how the ice crystal process

actually works we need to learn a little bit about clouds that

contain ice crystals - cold clouds.

Cold clouds

The figure below shows the interior of a

cold cloud.

The bottom of the thunderstorm, Point 1, is warm enough (warmer

than freezing) to just contain water droplets. The top of

the thunderstorm, Point 2, is colder than -40 F (which,

coincidentally, is equal to -40 C) and just contains ice

crystals. The interesting part of the thunderstorm and the

nimbostratus cloud is the middle part, Point 3, that contains both

supercooled water droplets (water that has been cooled to below

freezing but hasn't frozen) and ice crystals. This is called

the mixed phase region.

This is where the ice crystal process will be able to produce

precipitation. This is also where the electrical charge that

results in lightning is created.

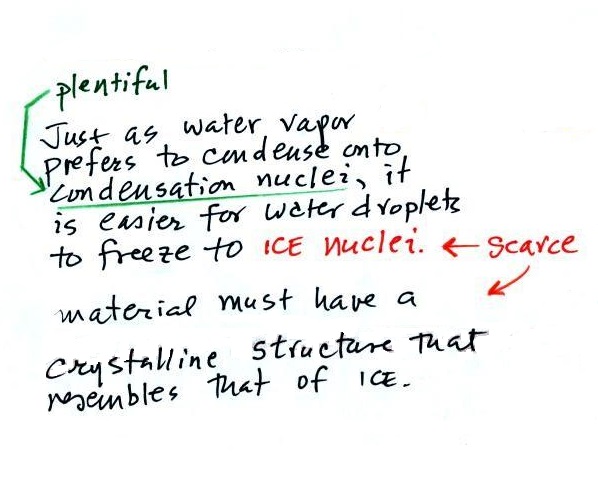

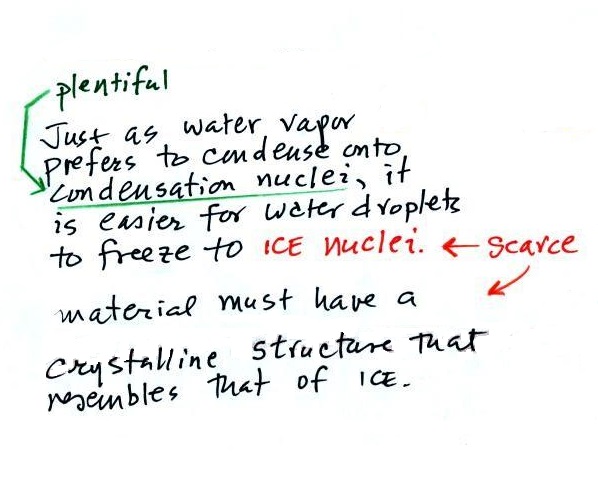

Ice crystal nuclei

The supercooled water droplets aren't able

to freeze even though they have been cooled below

freezing. This is because it is much easier for small

droplets of water to freeze onto an ice crystal nucleus (just

like it is easier for water vapor to condense onto

condensation nuclei rather than condensing and forming a small

droplet of pure water). Not just any material will work

as an ice nucleus however. The material must have a

crystalline structure that is like that of ice. There

just aren't very many materials with this property and as a

result ice crystal nuclei are rather scarce. In most of

the mixed phase region there are more supercooled water

droplets than ice crystals.

Supercooled water

Here are a couple of demonstrations involving supercooled water

that I showed in class. In the first

demonstration, some supercooled water (cooled to -6 F (-21

C)) is poured into a glass bowl sitting at room

temperature. Just pouring the water into the bowl is

enough of a "disturbance" to cause the supercooled water to

freeze. Just bumping a bottle of supercooled water in the second

video is enough to cause the water to freeze. I

don't know why that happens.

Superheated water

It is also possible to superheat water.

When the superheated water is disturbed it

suddenly and boils explosively. This

is a potentially dangerous demonstration to attempt, better to

watch a

video online.

Here are a some precautions just in case you're ever tempted to

try an experiment like this.

It is probably easier to superheat distilled water than ordinary

tap water. So you might put two cups of water into a

microwave, one with tap water the other filled with distilled

water. The cup of tap water will probably start boiling when

it is supposed to, i.e. before it can become superheated.

You can watch the tap water and get an idea of how long you need

to heat the distilled water to superheat it. I suspect

impurities in the tap water might act as nuclei to initiate the

boiling.

Then once you think you have superheated the cup of distilled

water be very careful taking it out of the microwave (better yet

leave it in the microwave). Just the slightest disturbance

might start the water boiling. You want your hands, arm,

body and faced covered and protected just in case this

happens. Tape a spoon onto the end of a long stick and put a

little sugar or salt into the spoon. Then drop the salt or

sugar into the cup of superheated water.

Chemists will often use "boiling chips" to make sure water will

start to boil when it is supposed to (at 212 F) rather than

becoming superheated.

Bubbles in beer or soda

Rather than superheating water, here's a far safer

experiment to try.

Carbonated drinks all contain dissolved carbon dioxide. The

drink containers are pressurized. When you open the can or

take the cap off the pressure inside is released and dissolved

carbon dioxide gas starts to come out of solution and forms small

bubbles. Often you will see the bubbles originate at a point

on the side or bottom of the glass. These are nucleation

sites and are often small scratches or pits on the surface of the

glass that are filled with a small bubble of air. You can

think of these bubbles of air as being "bubble nuclei." When

the carbon dioxide comes out of solution rather than forming a

small bubble of its own, it makes use of and builds on these

existing bubbles of air. The bubble, now a mixture of air

and carbon dioxide, grows until it is able to break free and float

to the surface (a little gas is left behind in the scratch so the

process can start over again).

This is actually a michelada, I think; a

mixture of beer, lime, and tomato juice(image

source) but that doesn't affect the bubble formation

The next time you are drinking one of these carbonated beverages

sprinkle in a few grains of sugar or salt. These will serve

as additional bubble nucleation sites and additional bubbles will

form. This is exactly what happened in the superheated water

demonstration above.

This is as far as I dared go in class

today. I've moved the rest of the information about the

formation of precipitation and types of precipitation to the

Monday, Apr. 4 notes.