Monday, Apr. 11, 2016

Marcus Roberts "Bolivar Blues"

(3:15), "I

Got Rhythm" (6:08), if you have some extra time you

really should watch this 60 Minutes segment on Marcus

Roberts, Hans Otahal "Bumble Boogie"

(4:36)

The Scientific Paper, revised Expt. #2, and a couple of Book

Reports have all been graded and were returned in class

today. You can revise your report if you want to (no need to

revise your report if you're happy with the grade you

received). The revised reports are due in two weeks, by

Mon., Apr. 25. Though if you could get them in before that

would be helpful. Please return your original report with

your revised report. This is especially important with the

Scientific Paper and Book Reports.

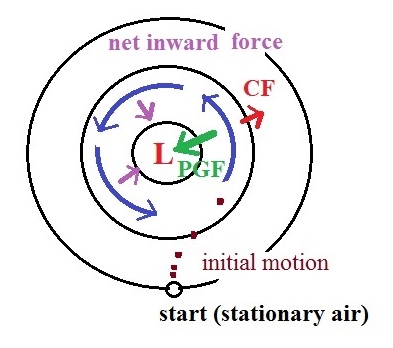

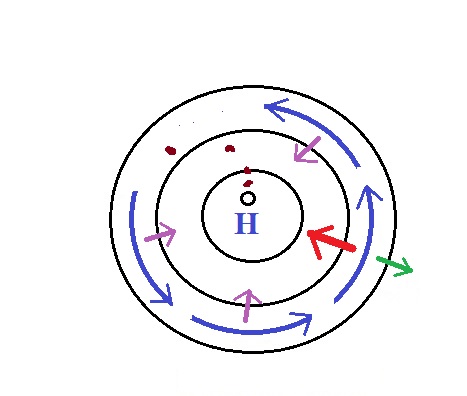

Step #5 - Upper level winds, low pressure, northern

hemisphere

Next we'll be looking at the upper level winds that develop around

circular centers of high and low pressure.

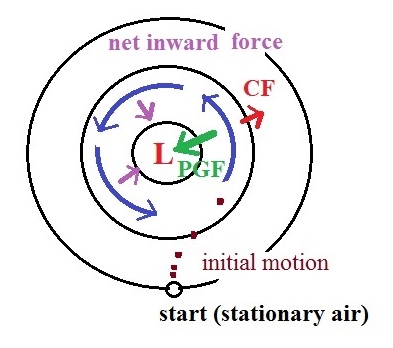

We start with some stationary air at the bottom of the

picture. Because the air is stationary, there is no

Coriolis force. There is a PGF force,

however. The PGF at

Point 1 starts stationary air moving toward the center of low

pressure (just like a rock would start to roll downhill).

The dots show the initial motion

A rock would roll right into the center of the picture.

Once air starts to move, the CF

causes it to turn to the right (because this is a northern

hemisphere chart). As the wind speeds up the CF strengthens. The wind

eventually ends up blowing parallel to the contour lines and

spinning in a counterclockwise direction. Note that the

inward PGF is stronger than

the outward CF. This

results in a net inward force,

something that is needed anytime wind blows in a circular path.

Upper level winds spin counterclockwise around low pressure

in the northern hemisphere.

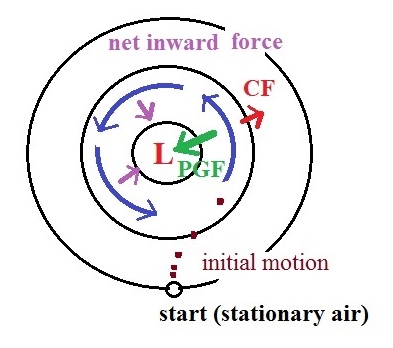

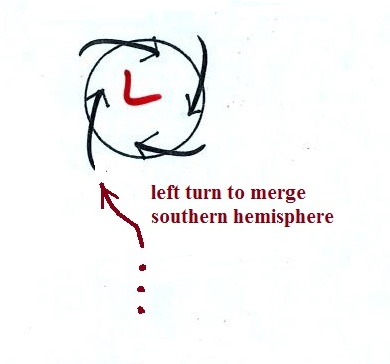

Step #6 - Upper level winds, low pressure, southern

hemisphere

We start again with some stationary air at Point 1 in this

figure. The situation is very similar. Air starts to

move toward the center of the picture but then takes a left hand

turn (the CF is to the left

of the wind in the southern hemisphere). The winds end up

spinning in a clockwise direction around low in the southern

hemisphere. The directions of the PGF, CF,

and the net inward force

are all shown in the picture.

Upper level winds spin clockwise around low pressure in the

southern hemisphere.

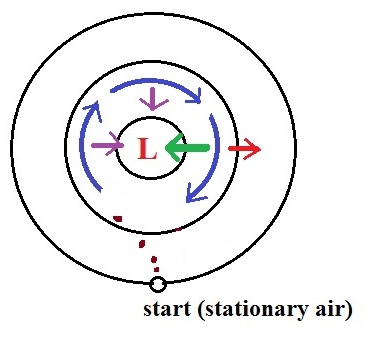

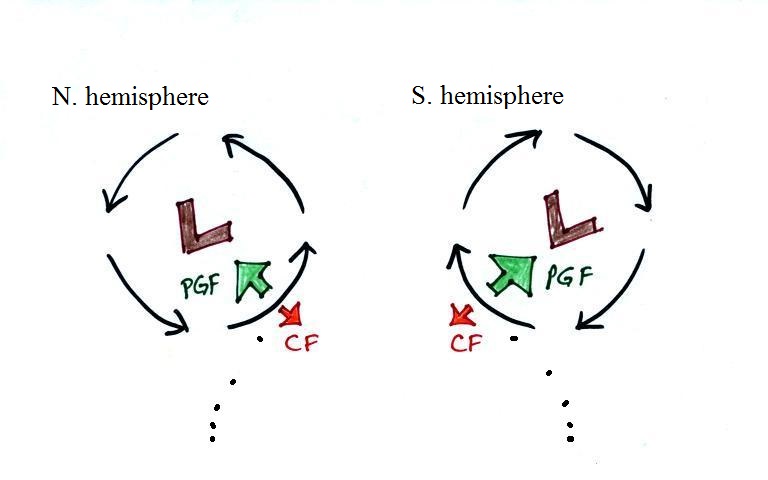

Step #7 - Upper level winds, high pressure, northern

hemisphere

Here initially stationary air near the center of the picture

begins to move outward in response to an outward pointing

pressure gradient force (PGF

is pointing toward low pressure which is on the edges of the

picture). Once the air starts to move, the Coriolis force

(CF) will cause the wind to

turn to the right. The dots show the initial outward

motion and the turn to the right. The wind ends up blowing

in a clockwise direction around the high. The inward

pointing CF is stronger

than the PGF so there is a

net inward force here just

as there was with the two previous examples involving low

pressure. An inward force is need with high pressure

centers as well as with centers of low pressure. An inward

force is needed anytime something moves in a circular path.

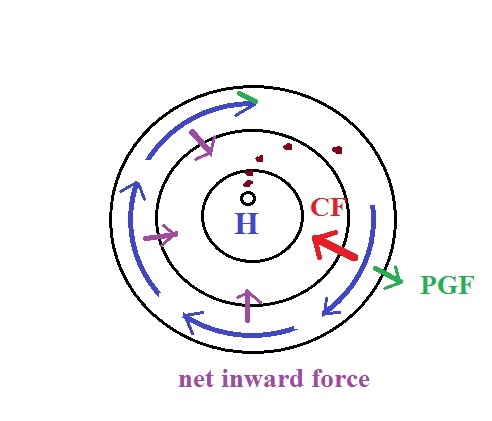

Step #8 - Upper level winds, high pressure, southern

hemisphere

This is a southern hemisphere upper level center of high

pressure. The air starts to move outward again but

this time takes a left hand turn and ends up spinning

counterclockwise. The net force is inward again.

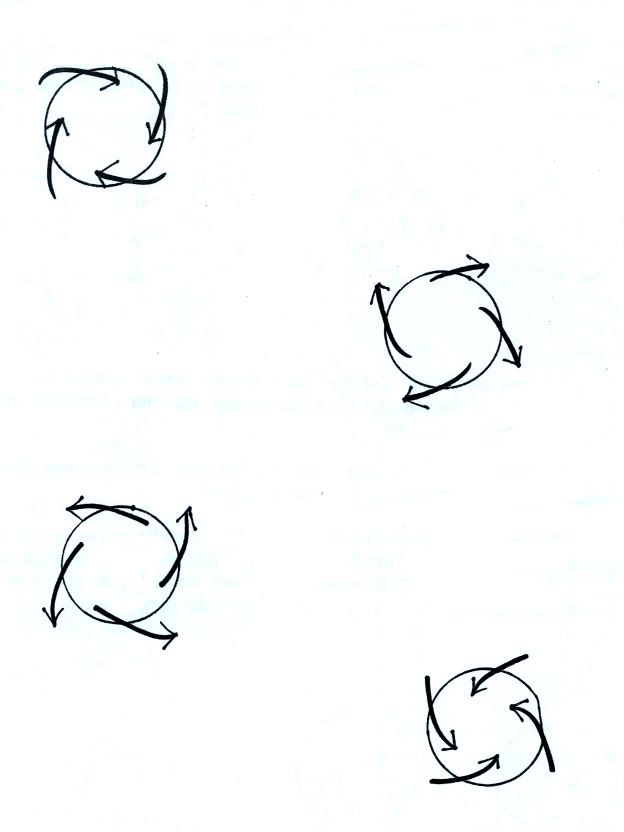

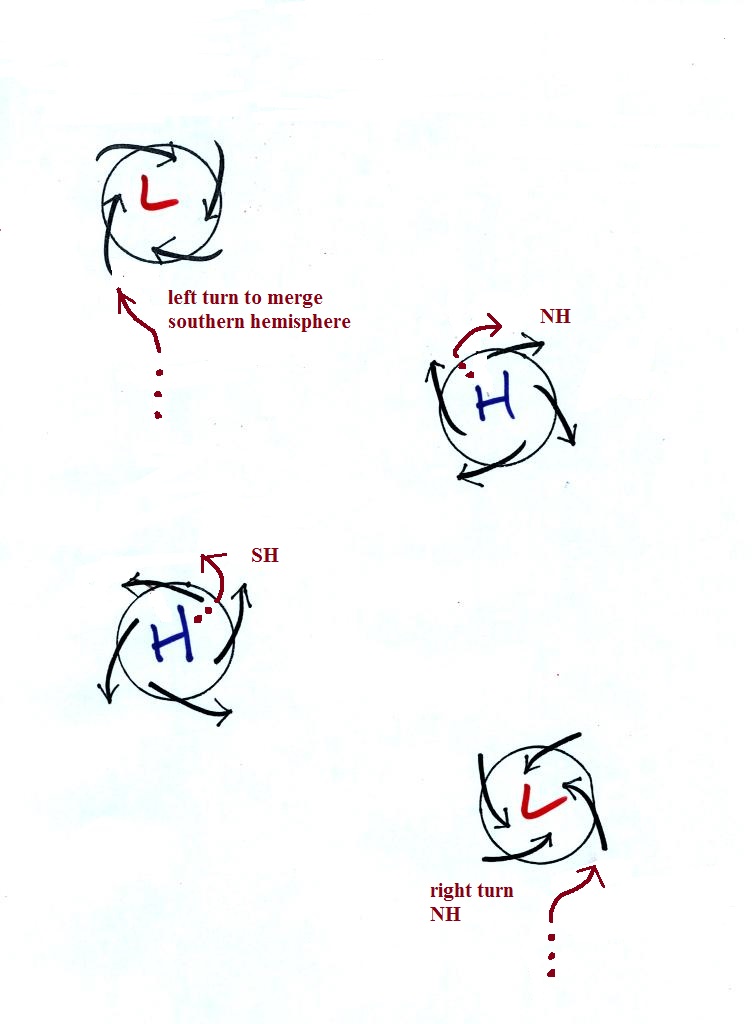

Upper level winds review

Here's a quick review of much of what we covered

in class on Tuesday. Many of the figures below were on a

handout distributed in class today.

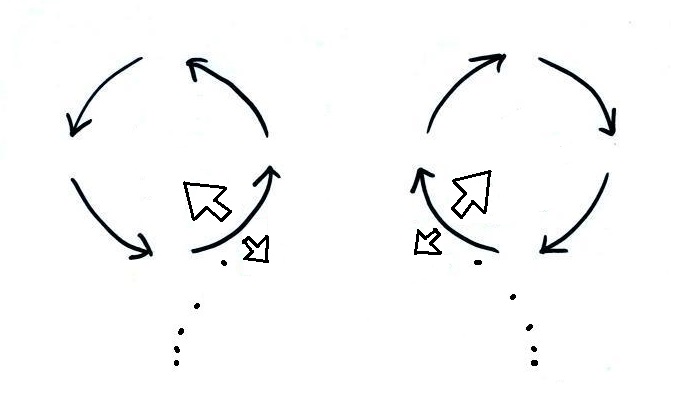

Winds

spin counterclockwise around L pressure in the

northern hemisphere then switch direction and spin

clockwise around L pressure in the southern

hemisphere. I think by just remembering a

couple of things you can figure this out rather than

just trying to memorize it.

The pressure

gradient will start stationary air moving toward low pressure

(just like a rock placed on a slope will start to move

downhill)

The dots in the figure

above show this initial motion and its in toward the

center of the picture. These must both be

centers of Low pressure. Then the wind will turn

to the right or left depending on the

hemisphere. This is the effect of the Coriolis

force, the CF turns wind to the right in the northern

hemisphere and to the left in the southern hemisphere.

The

northern hemisphere winds are shown at left in the

figure above, the southern hemisphere winds are

shown at right. The inward pointing force is

always stronger than the outward force so that there

is a net inward pointing force.

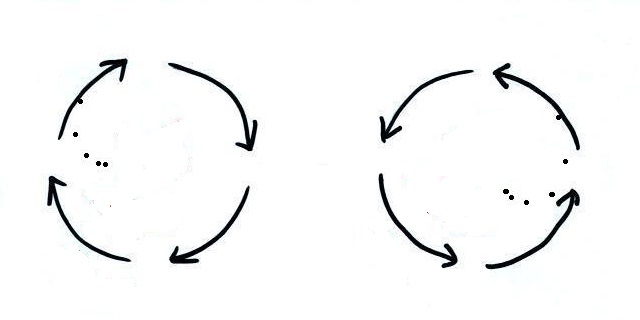

This initial motion is outward away from the center in the

two figures below.

The outward moving air takes a right turn in the left

figure above, a left turn in the right figure (you may need to

rotate the picture so that you are looking downstream, in the

direction the wind is blowing to clearly see the left hand

turn).

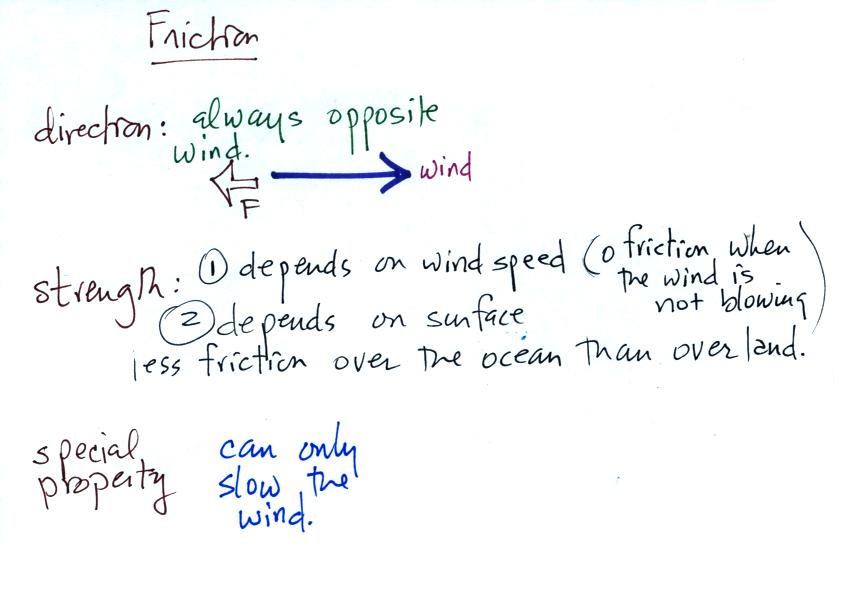

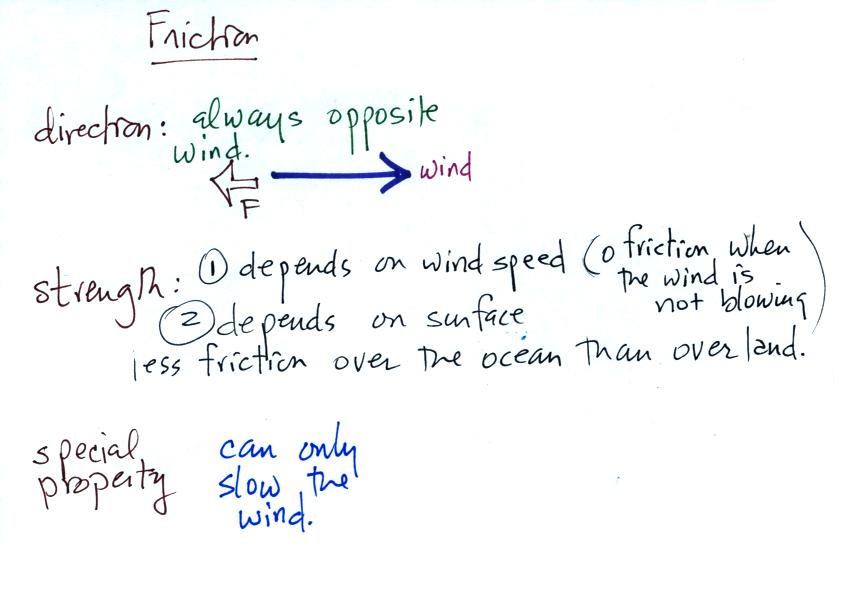

Friction and surface winds

Next we'll try to understand why friction causes surface winds

to blow across the contour lines (always toward low pressure).

With surface winds we need to take into account the PGF, the CF, and

the frictional force (F). That means we'll need some rules

for the direction and strength of the frictional force.

Friction arises with surface winds because the air is blowing

across (rubbing against) the earth's surface.

You're probably somewhat familiar with the effects of

friction. If you stop pedaling your bicycle on a flat road

you will slow down and eventually come to a stop due to air

friction and friction between the tires and road surface.

Friction always acts to slow a moving object it must point in a

direction opposite the motion.

The strength of the frictional force depends on wind speed.

The faster you try to go the harder it becomes because of

increased wind resistance. It's harder to ride on a rough

road than on a smooth road surface. In the case of air there

is less friction when wind blows over the ocean than when the air

blows over land. If the wind isn't blowing there isn't any

friction at all.

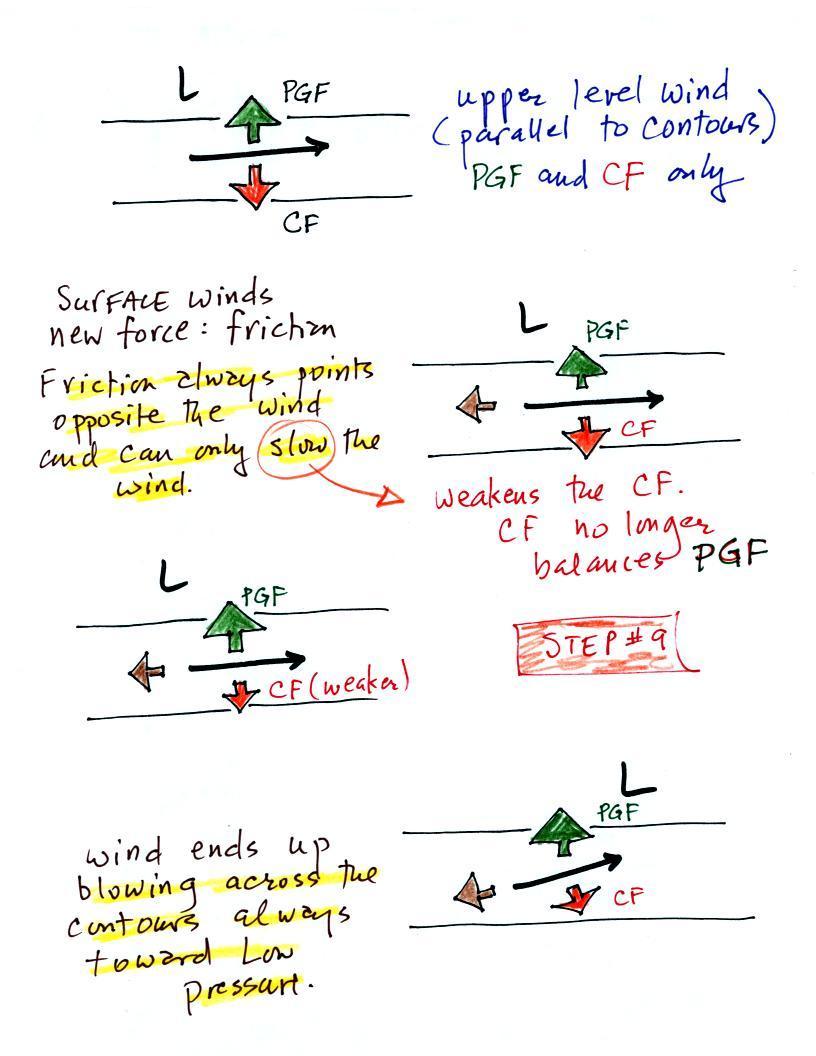

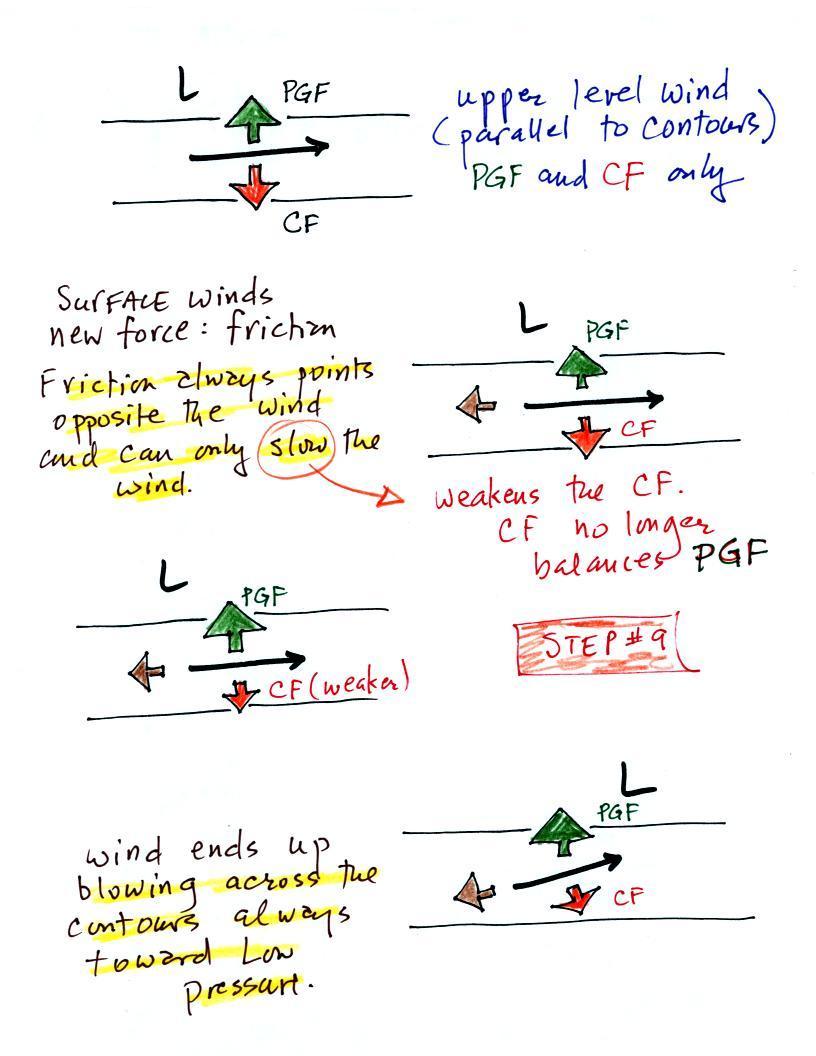

The top figure (p. 128 in the ClassNotes) shows upper

level winds blowing parallel to straight contours.

The PGF and CF point in opposite directions and have the same

strength (the fact that there are only two forces present

tells you these are upper level winds). Note the CF is

to the right of the wind, this is a northern hemisphere

case. The total force, the net force, is zero. The

winds would blow in a straight line at constant speed.

We add friction in the second picture. It points in a

direction opposite the wind and acts to slow the wind

down.

Slowing the wind weakens the CF and it can no longer balance

the PGF (3rd figure). The stronger PGF causes the wind

to turn and start to blow across the contours toward

Low. This is shown in the 4th figure.

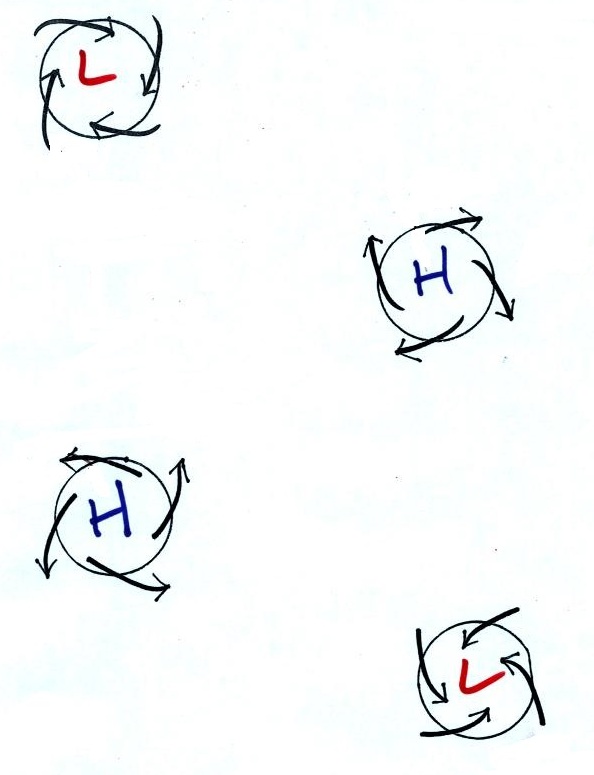

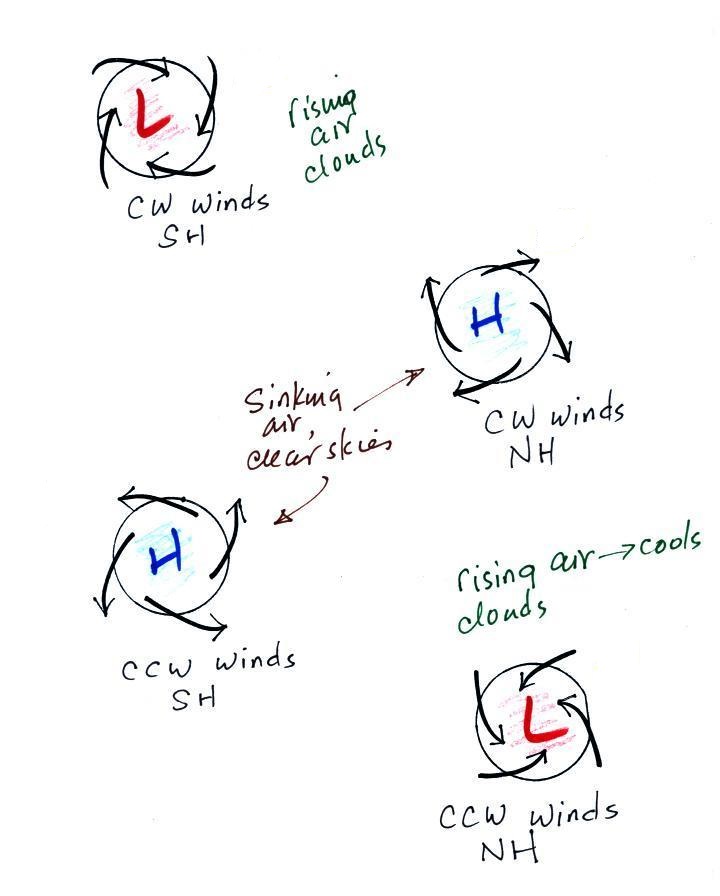

Step #10 - Surface winds blowing around H & L

pressure in the N. & S. hemispheres.

I think you'll be surprised at how easy it

is to determine whether each of the figures below (p. 129 in

the ClassNotes) is a surface center of H or L pressure,

found in the N or S hemisphere, and whether rising

or sinking air motions/clear or cloudy skies would be

associated with each figure.

Key point to remember:

surface winds blow across the contours always toward

low pressure.

It should be very easy to figure

out which two of the figures above are surface centers of low

and high pressure.

Next to determine whether each figure is in the northern

or southern hemisphere we will imagine approaching the upper left

figure in an automobile. We'll imagine it's a traffic circle

and the arrows represent cars instead of wind.

You're approaching the traffic

circle, what direction would you need to turn in order to

merge with the other cars. In this case it's

left. That left turn is the Coriolis force at work

and tells you this is a southern hemisphere map.

The remaining examples are shown below

Converging winds cause air to rise. Rising air expands and

cools and can cause clouds to form. Clouds and stormy

weather are associated with surface low pressure in both

hemispheres. Diverging winds created sinking wind motions

and result in clear skies.

Somethings change when you move form the northern to the

southern hemisphere (direction of the spinning winds).

Sometimes stay the same (winds spiral inward around centers of low

pressure in both hemispheres, rising air motions are found with

centers of low pressure in both hemispheres).

This is as far as we could get in

class today. We'll finish up the remaining material on

this topic in class on Wednesday.