Wednesday, Apr. 13, 2016

Noora Noor "Forget What I

Said" (3:18), Iyeoka "Simply

Falling" (3:57), Danger Mouse, Daniele Luppi, & Norah

Jones "Black"

(3:41)

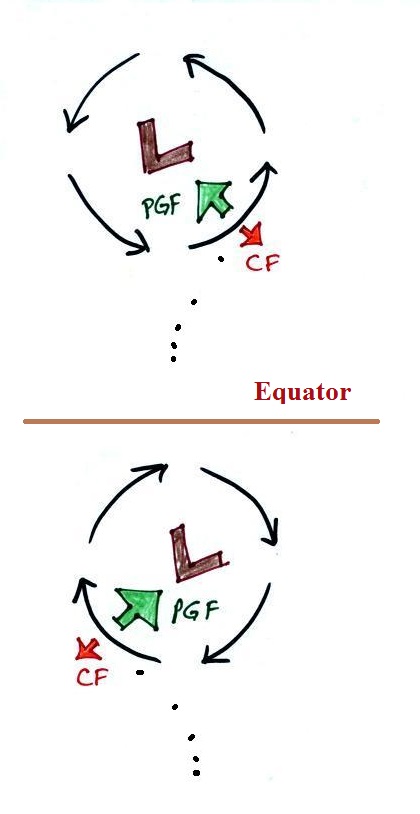

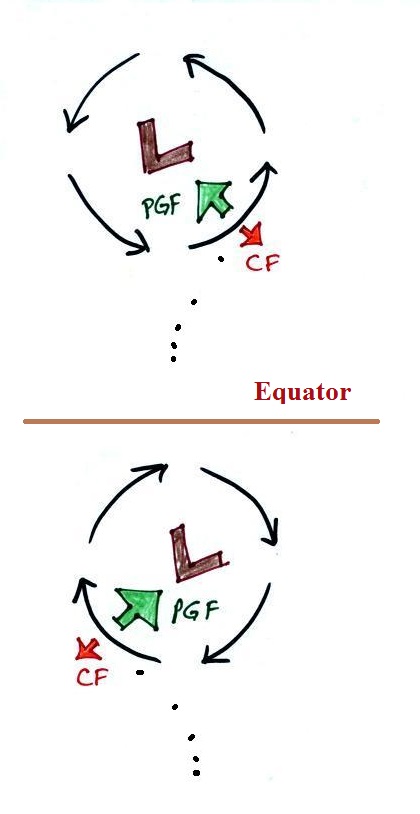

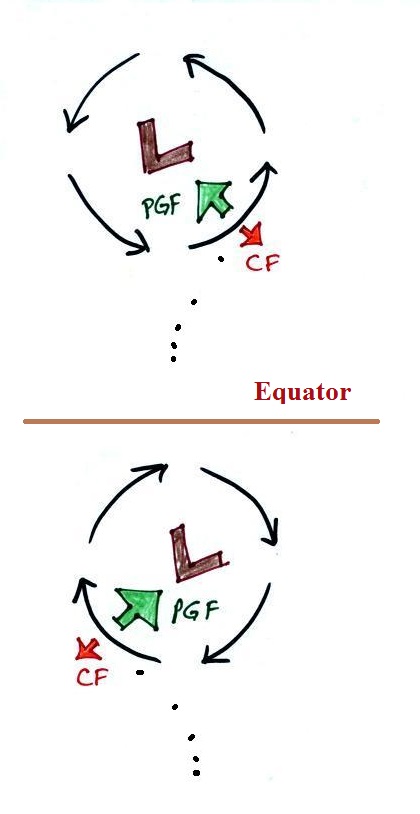

Spinning motions in cases where the PGF is

stronger than the Coriolis force

The situations we have been looking at so far are

representative of large "country size" storm systems.

There are smaller scale situations, though, where the PGF is

much stronger than the CF and the CF can be ignored. A tornado

is an example. Spinning water draining from a sink or

toilet is another. The PGF is much much stronger than

the CF and the CF can be ignored.

|

|

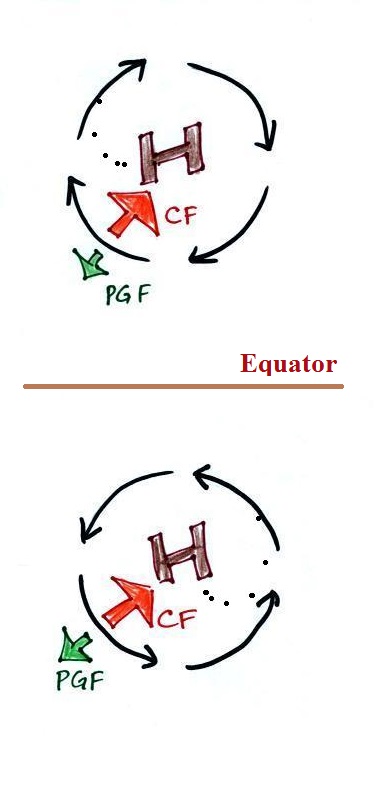

Large scale winds upper level winds

blowing around Low pressure. You must take

into account both PGF and CF forces. Winds only spin in a

CCW direction around L in the northern hemisphere and

change direction in the southern hemisphere.

|

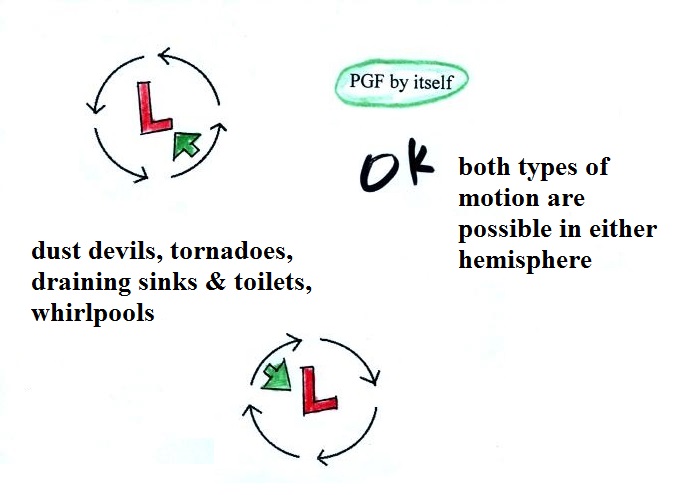

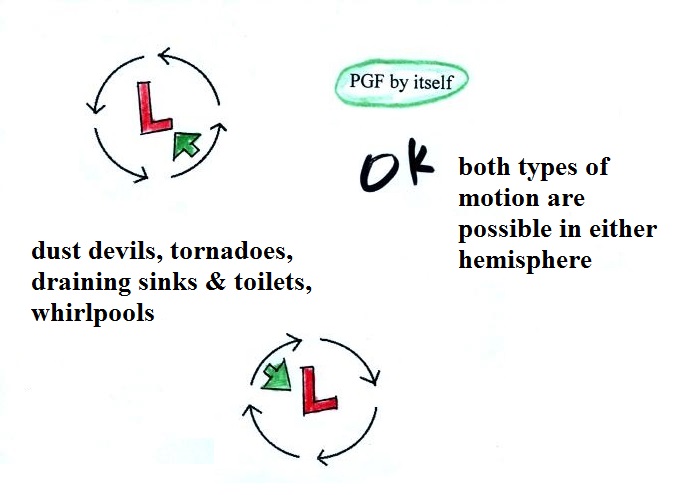

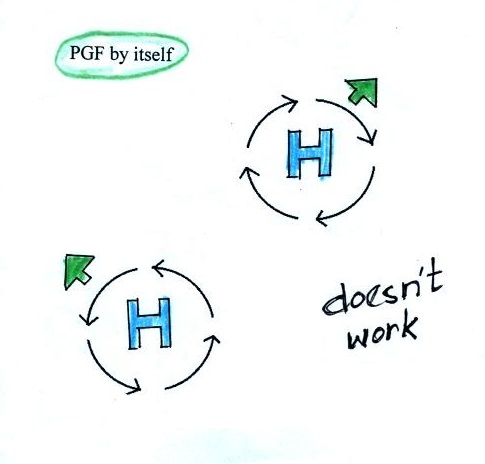

A net inward force is need

to keep winds spinning in a circular path. The

inward pointing PGF provides the needed net inward force

in this case and winds can spin in either direction

around the L in either hemisphere.

|

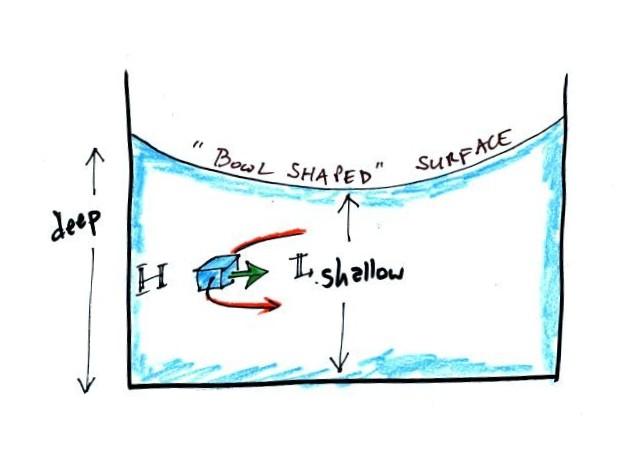

Water

draining from a sink or toilet

- direction of spin

This is what happens when water

drains from a sink or

toilet. The PGF is present,

there is no CF. The water

can spin in either direction in

either hemisphere. It might

not be obvious though what causes

the inward pointing PGF in the

case of spinning water.

If you look carefully

at some spinning water you'll notice the surface has a

"bowl" or "funnel" shape as sketched above. The

water at the edges is a little deeper. That

additional water has more weight and produces more

pressure. The water in the middle is shallower,

doesn't weigh as much and the pressure is lower.

Thus there is a PGF pointing from the edges into the

center of the vortex.

Here's a picture of the "Old Sow" whirlpool in the Bay of

Fundy (located between the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick

and Nova Scotia). It is apparently the largest whirlpool

in the Western Hemisphere (source).

The Bay of Fundy also has some of the highest tides in the

world.

The Great Toilet Flushing Experiment

You may have heard that water draining from a sink or flushed

toilet spins in a different direction in the southern hemisphere

than it does here in the northern hemisphere. As mentioned

above there are situations where the pressure gradient force is

much stronger than the Coriolis force. In these situations

clockwise or counterclockwise spin should be equally likely.

For the past few years we've been conducting and experiment in

ATMO 170 to see if this is indeed the case. Students would

go out, note the direction of spin after flushing a toilet, and

report back to me. Because the Coriolis force does not play

a role, we should expect to see roughly

equal numbers of reports of clockwise (CW) and

counterclockwise (CCW) spin. Here's the summary of

results after the Fall 2015 version of the experiment.

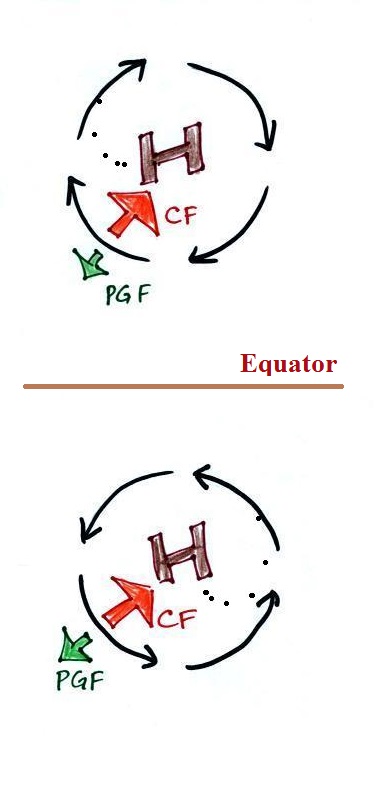

It isn't possible to find spinning winds

around high pressure when the CF is not present?

|

|

The CF plays an important

role here, it is the force that provides the net inward

force needed to keep the winds blowing in a circular

trajectory.

|

With just the

PGF there's nothing to provide a net inward force.

Circular winds around centers of high pressure is not

possible when there is no CF.

|

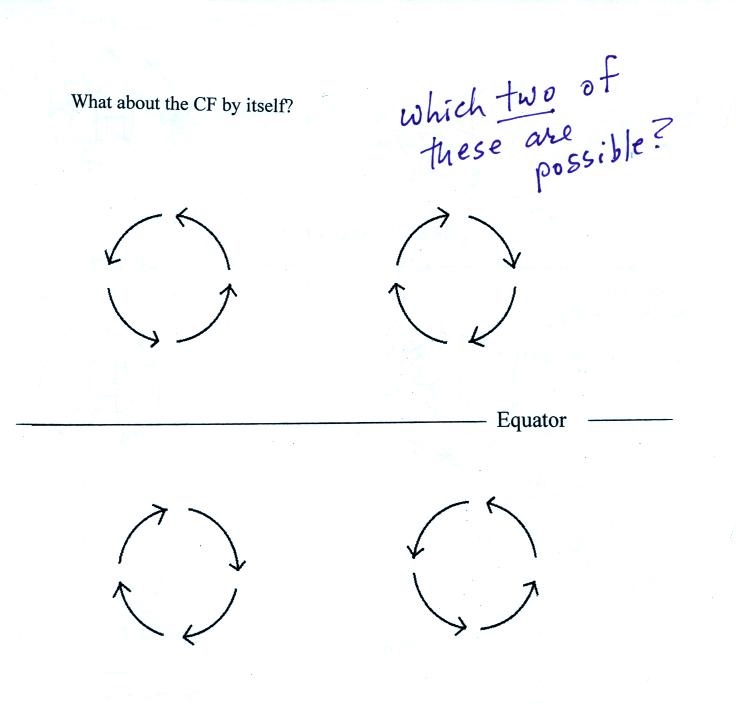

What if just the Coriolis force were present?

The following figure is on the back of the class handout.

Which of these would be possible if just the CF were present?

When you think you have the answer, click here.

Thunderstorms introduction

Severe thunderstorms in Texas Sunday night with baseball size

hail (report

from the Lubbock National Weather Service Forecast Office)

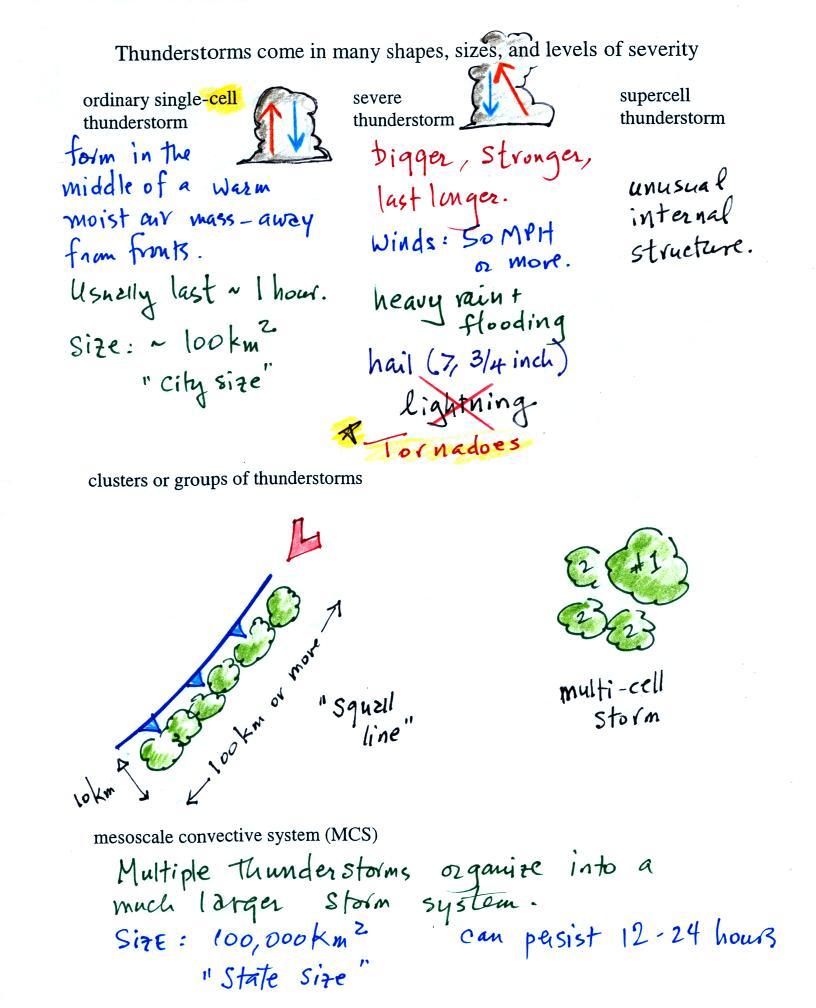

Thunderstorms come in different sizes and levels of

severity. We will mostly be concerned with ordinary

single-cell thunderstorms (also referred to as air mass

thunderstorms). They form in the middle of warm moist air,

away from fronts. Most summer thunderstorms in Tucson are

this type. An air mass thunderstorm has a vertical

updraft. A cell is just a term that means a single

thunderstorm "unit" (a storm with an updraft and a downdraft).

Tilted updrafts are found in severe and supercell

thunderstorms. As we shall see this allows those storms to

get bigger, stronger, and last longer. The

tilted updraft will sometimes begin to rotate. We'll see

this produces an interesting cloud feature called a wall cloud and

maybe tornadoes. Supercell thunderstorms have a

complex internal structure; we'll watch a short video at

some point that shows a computer simulation of the complex air

motions inside a supercell thunderstorm. In class

I showed a gallery of

storm images that were taken by Mike Olbinski. The 1st

and 5th images in the gallery show the base of a supercell

thunderstorms photographed in Texas with wall clouds.

There are additional images further down in the gallery.

We won't spend anytime discussing mesoscale convective systems

except to say that they are a much larger storm system. They

can cover a large portion of a state. They move slowly and

often thunderstorm activity can persist for much of a day.

Occasionally in the summer in Tucson we'll have activity that

lasts throughout the night. This is often caused by an MCS.

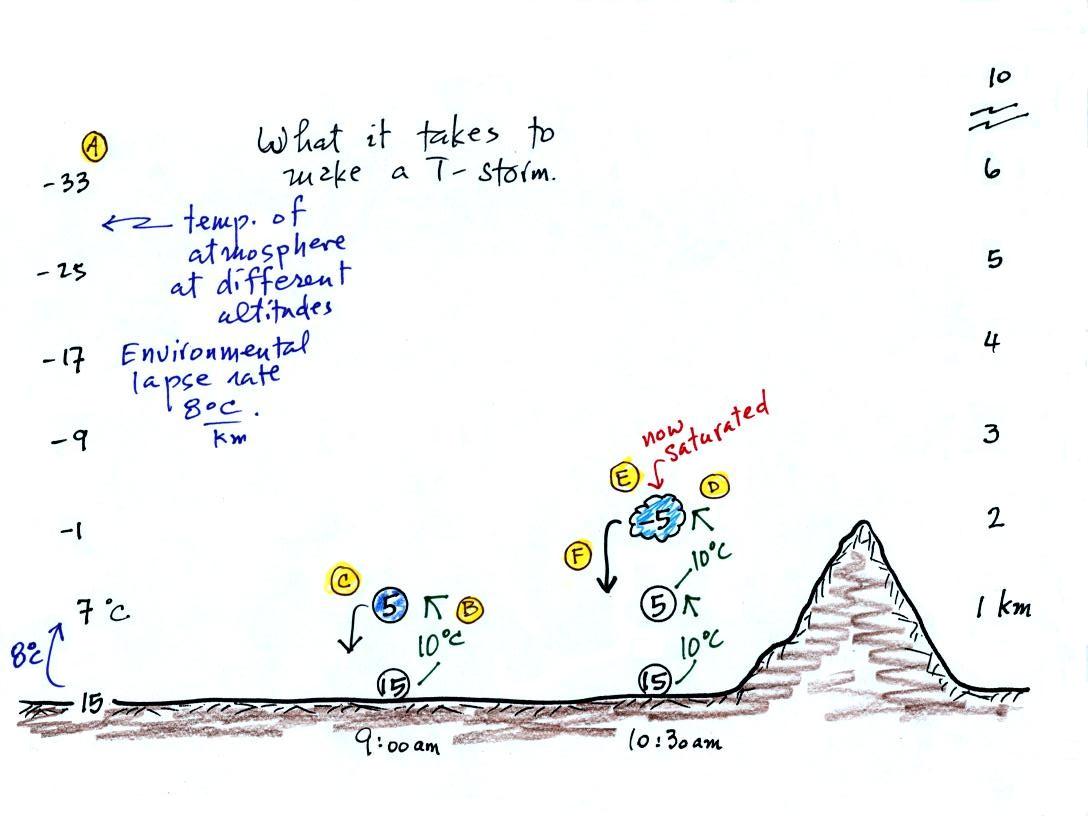

The buildup to an air mass thunderstorm

The following somewhat tedious material is intended to

prepare you to better appreciate a time lapse video movie of a

thunderstorm developing over the Catalina mountains. The

newest 1S1P/Optional Assignment makes uses of a couple of the

numbers below (the rates of cooling of rising parcels of

unsaturated and saturated air).

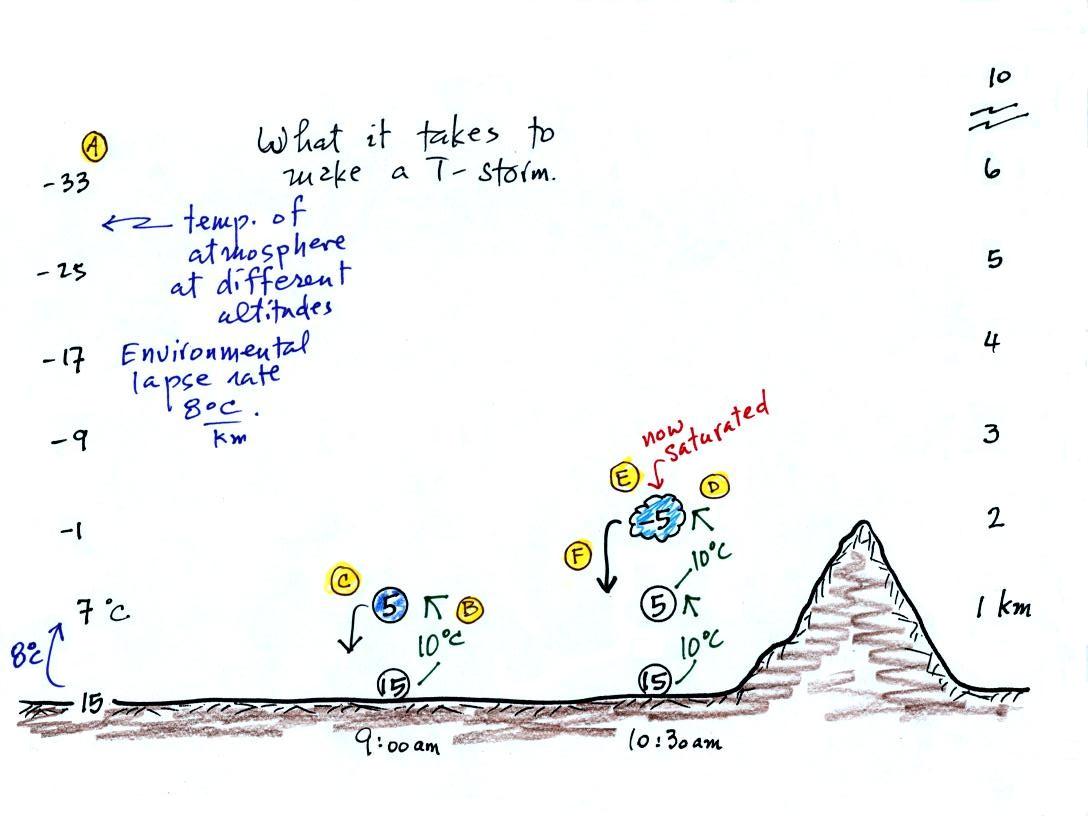

Refer back and forth between the lettered points in the

figure above and the commentary below.

The numbers in Column A

show the temperature of the air in the atmosphere at various

altitudes above the ground (note the altitude scale on the right

edge of the figure). On this particular day the air

temperature was decreasing at a rate of 8 C per kilometer.

This rate of decrease is referred to as the environmental lapse

rate (lapse rate just means rate of decrease with altitude).

Temperature could decrease more quickly than shown here or less

rapidly. Temperature in the atmosphere can even increase

with increasing altitude (a temperature inversion).

At Point B, some

of the surface air is put into an imaginary container, a

parcel. Then a meteorological process of some kind lifts the

air to 1 km altitude (in Arizona in the summer, sunlight heats the

ground and air in contact with the ground, the warm air becomes

buoyant - that's called free convection). The rising air

will expand and cool as it is rising. Unsaturated air (RH

is less than 100%) cools at a rate of

10 C per kilometer. So the 15 C surface air will have

a temperature of 5 C once it arrives at 1 km altitude.

Early in the morning "Mother Nature" is only able to lift the

parcel to 1 km and "then lets go." At Point C note that the

air inside the parcel is slightly colder than the air outside (5 C

inside versus 7 C outside). The air inside the parcel will

be denser than the air outside and the parcel will sink back to

the ground. You can't see this because the air is clear,

invisible.

By 10:30 am the parcel is being lifted to 2 km as shown at Point D. It is

still cooling 10 C for every kilometer of altitude gain. At

2 km, at Point E

the air has cooled to its dew point temperature, the

relative humidity is now 100%, and a cloud has formed.

A dew point temperature of -5 C was used in this example. It

could be warmer or colder than that.

Notice at Point F,

the air in the parcel or in the cloud (-5 C) is still colder and

denser than the surrounding air (-1 C), so the air will sink back

to the ground and the cloud will disappear. Still no

thunderstorm at this point.

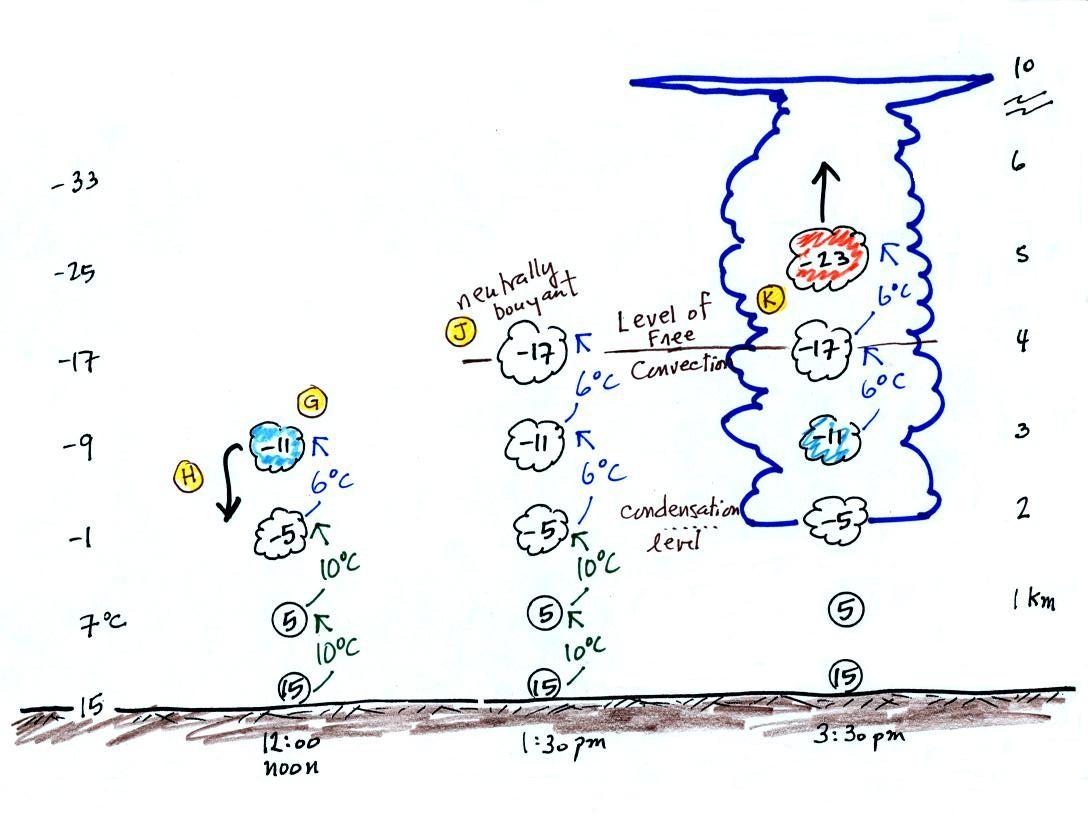

At noon, the air is lifted to 3 km. Because the air

became saturated at 2 km, it will cool at a different rate between

2 and 3 kilometers altitude. Saturated air cools at a

rate of 6 C/km instead of 10 C/km. The saturated air

cools more slowly because release of latent heat during

condensation offsets some of the cooling due to expansion.

The air that arrives at 3km, Point H, is again still colder than the

surrounding air and will sink back down to the surface.

By 1:30 pm the air is getting high enough that it has become

neutrally buoyant, it has the same temperature and density as the

air around it (-17 C inside and -17 C outside). This is

called the level of free convection, Point J in the figure.

If you can, somehow or another, lift air above the level

of free convection it will find itself warmer and less dense than

the surrounding air as shown at Point K and will float upward to

the top of the troposphere on its own, it doesn't need Mother

Nature's help anymore. This is really the beginning

of a thunderstorm. The thunderstorm will grow

upward until it reaches very stable air at the bottom of the

stratosphere the rising air will quickly become colder and denser

than the surrounding air if it travels into the stratosphere).

Here's a time

lapse video showing a day's worth of work leading eventually

to the development of a thunderstorm over the Catalina mountains

north of Tucson (Firefox seems to have trouble sometimes

downloading the file, you may need to use another browser).

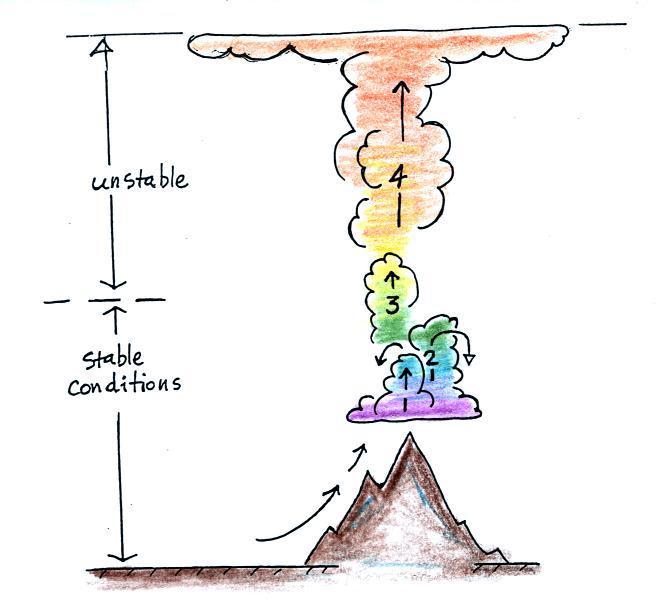

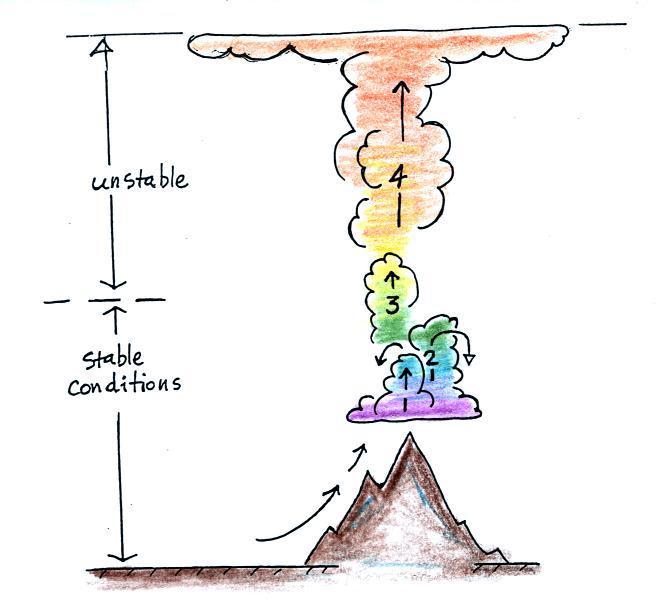

Air mass thunderstorm life cycle

The events leading up to the initiation of a summer air

mass thunderstorm are summarized in the figure below (p. 151 in

the ClassNotes). It

takes some effort and often a good part of the day before a

thunderstorm forms. The air must be lifted to just above

the level of free convection (the dotted line at middle left in

the picture). Once air is lifted above the level of free

convection it finds itself warmer and less dense that the air

around it and floats upward on its own. I've tried to show this with colors below.

Cool colors below the level of free convection because the air

in the lifted parcel is colder and denser than its

surroundings. Warm colors above the dotted line indicate

parcel air that is warmer and less dense than the

surroundings. Once the parcel is lifted above the level

of free convection it becomes buoyant; this is the

moment at which the air mass thunderstorm begins.

Once an air mass

thunderstorm gets above the level of free convection it goes

through a 3-stage life cycle

In

the first stage you would only find updrafts inside the cloud

(that's all you need to know about this stage, you don't even

need to remember the name of the stage).

Once precipitation has formed and grown to a certain size, it

will begin to fall and drag air downward with it. This

is the beginning of the mature stage where you find both an

updraft and a downdraft inside the cloud. The falling

precipitation will also pull in dry air from outside the

thunderstorm (this is called entrainment). Precipitation

will mix with this drier air and evaporate. The

evaporation will strengthen the downdraft (the evaporation

cools the air and makes it denser).

The thunderstorm is strongest in the mature stage. This

is when the heaviest rain, hail, strongest winds, and most of

the lightning occur.

Eventually the downdraft spreads

horizontally throughout the inside of the cloud and begins to

interfere with the updraft. This marks the beginning of

the end for this thunderstorm.

The downdraft

eventually fills the interior of the cloud. In this

dissipating stage you would only find weak downdrafts

throughout the cloud.

Note how the winds from one

thunderstorm can cause a region of convergence on one side of

the original storm and can lead to the development of new

storms. Preexisting winds refers to winds that were

blowing before the thunderstorm formed. Convergence

between the prexisting and the thunderstorm downdraft winds

creates rising air that can initiate a new thunderstorm.

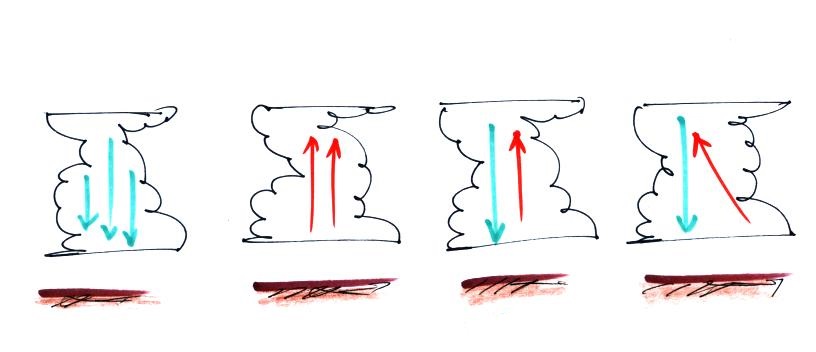

Here's a sketch of 4 thunderstorm clouds, what

information could you add to each picture.

You should be able to say something about the first

three. The 4th cloud might be a bit of a puzzle.

You'll find the answer at the very beginning of this sections on

thunderstorms.