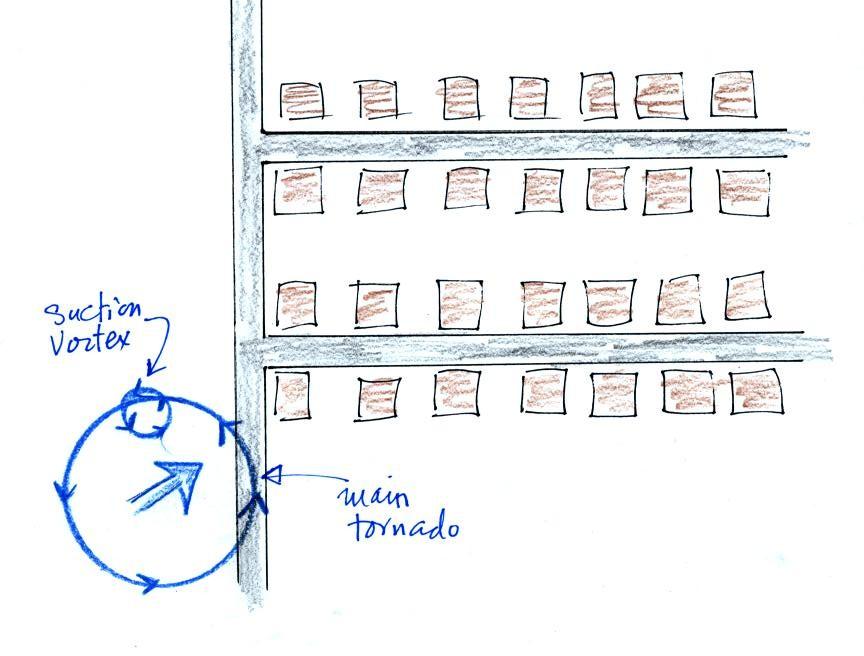

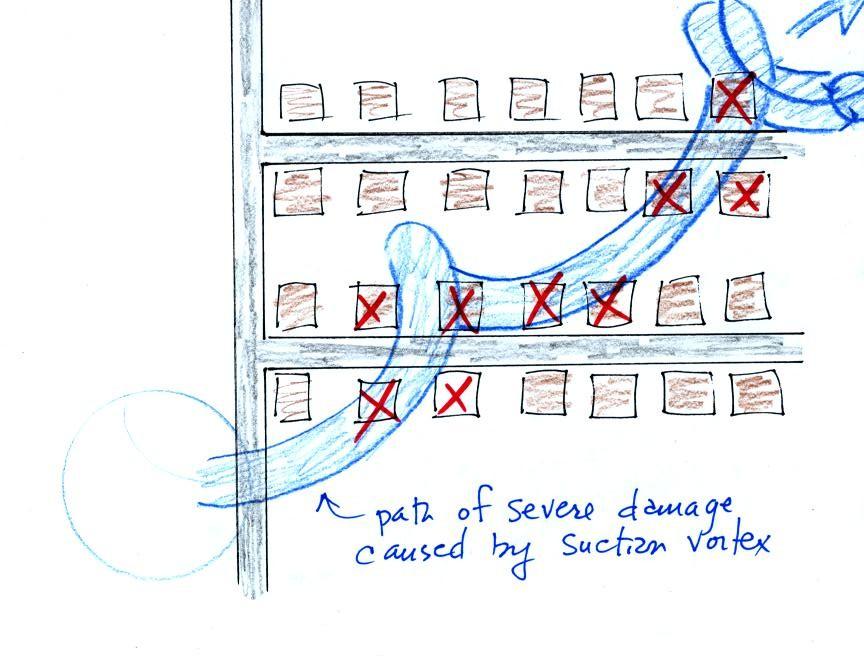

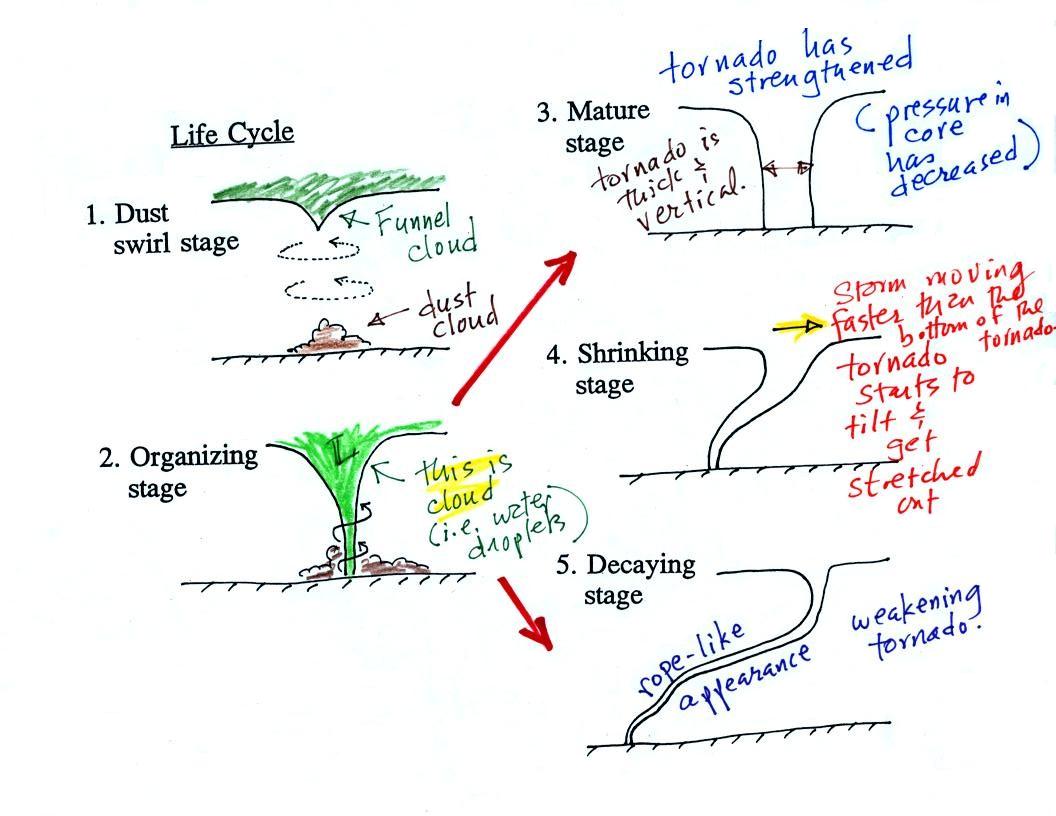

Tornadoes begin in and descend from a thunderstorm. You would usually see a funnel cloud dropping from the base of the thunderstorm. Spinning winds will probably be present between the cloud and ground before the tornado cloud becomes visible. The spinning winds can stir up dust at ground level. The spinning winds might also be strong enough at this point to produce some minor damage.

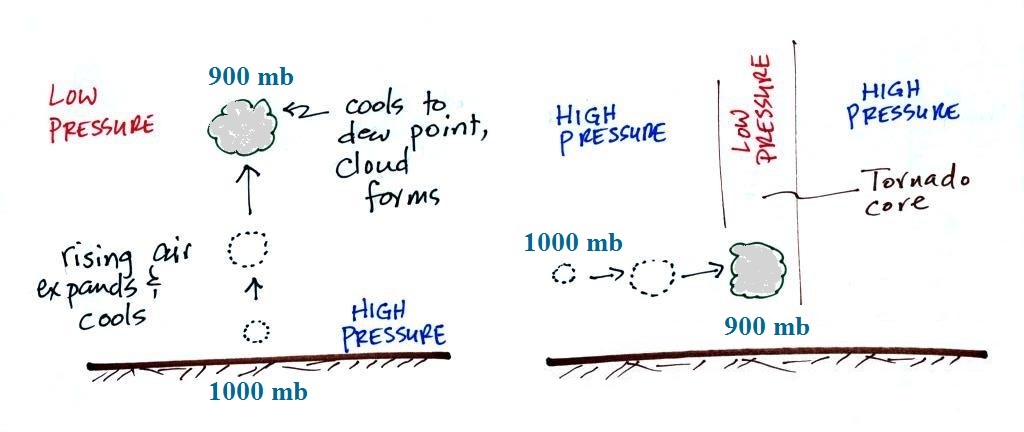

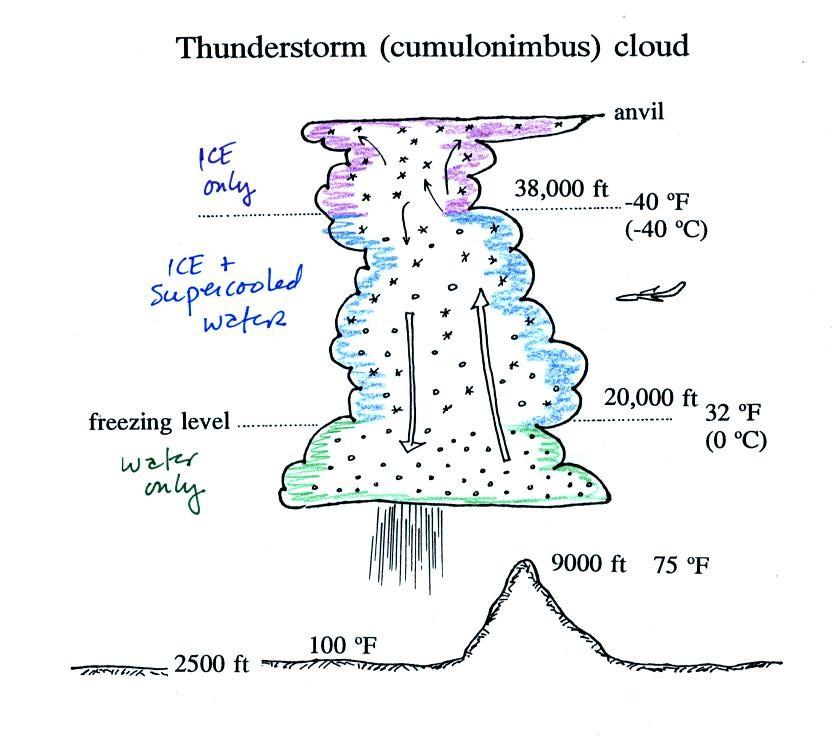

In Stage 2, moist air moves horizontally toward the low pressure in the core of the tornado. This sideways moving air will expand and cool just as rising air does (see figure below). Once the air cools enough (to the dew point temperature) a cloud will form.

Tornadoes can go from Stage 2 to Stage 3 (this is what the strongest tornadoes do) or directly from stage 2 to stage 4 or 5. Note a strong tornado is usually vertical and thick as shown in Stage 3. "Wedge tornadoes" actually appear wider than they are tall.

Here is video of the Laverne Oklahoma tornado that was shown in class and that shows the initial dust swirl stage up to the mature stage very well.

The thunderstorm and the top of the tornado will move faster than the surface winds and the bottom of the tornado. This will tilt and stretch the tornado. The rope like appearance in Stage 5 is usually a sign of a weakening (though still a dangerous) tornado.