Monday, Feb. 1, 2016

Calexico

at Ancienne Belgique "Falling From the Sky" (0 - 4:20),

"Moon Never Rises" (27:00 - 31:30), "Beneath the City

of Dreams" (46:55 - 50:40)

We'll start with a topic

that we didn't have time to cover in class last Friday.

Changes in air density with

altitude

(see p. 34 in the ClassNotes)

We've spent a lot of time (too much?) looking at

air pressure and how it changes with altitude. Next

we'll consider air density.

How does air density change with increasing

altitude? You should know the answer to that

question. You get out of breath more easily at high

altitude than at sea level. Air gets thinner (less

dense) at higher altitude. A lungful of air at high

altitude just doesn't contain as many oxygen molecules as it

does at lower altitude or at sea level.

It would be nice to also understand why air density

decreases with increasing altitude.

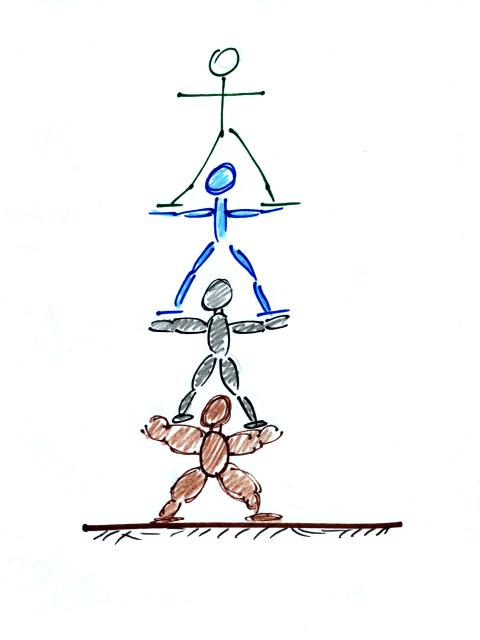

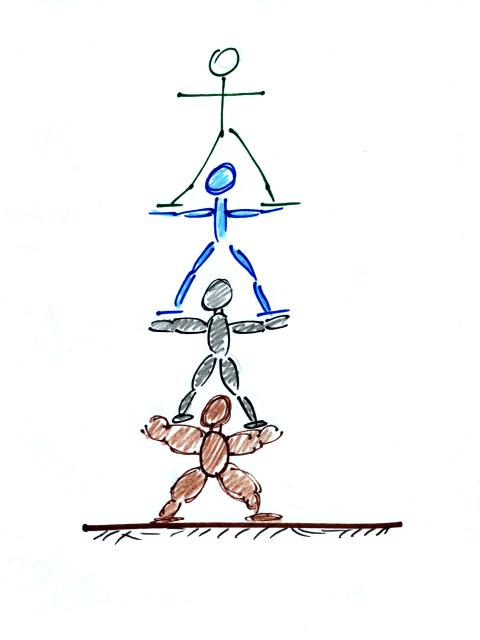

The people pyramid reminds you that there is more

weight, more pressure, at the bottom of the atmosphere than there

is higher up.

Layers of air are not solid and rigid like in a stack of

bricks. Layers of air are more like mattresses stacked on

top of each other. Mattresses are compressible,

bricks (and people) aren't. Mattresses are also reasonably

heavy, the mattress at the bottom of the pile would be squished by

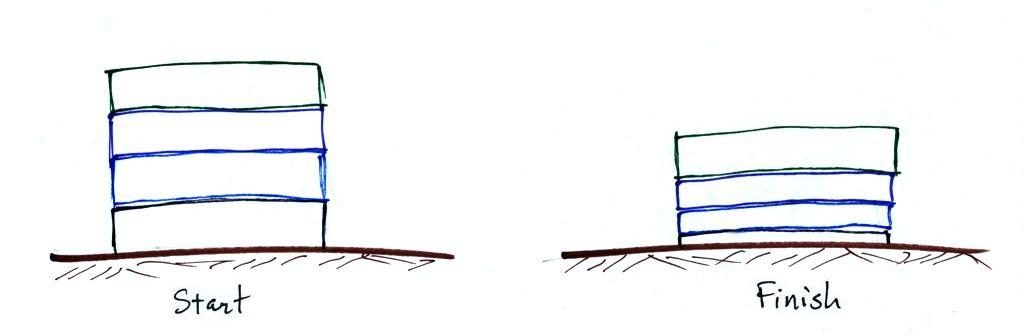

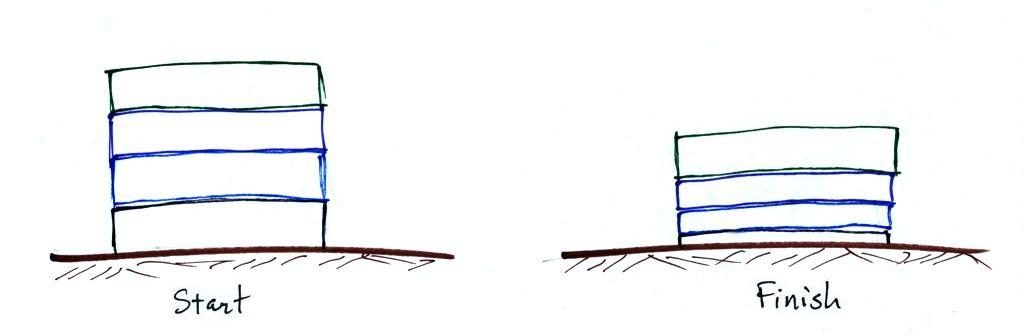

the weight of the three mattresses above. This is shown at

right. The mattresses higher up aren't compressed as much

because there is less weight remaining above. The same is

true with layers of air in the atmosphere.

The statement above is at the top of p. 34 in the photocopied

ClassNotes. I've redrawn the figure found at the bottom of

p. 34 below.

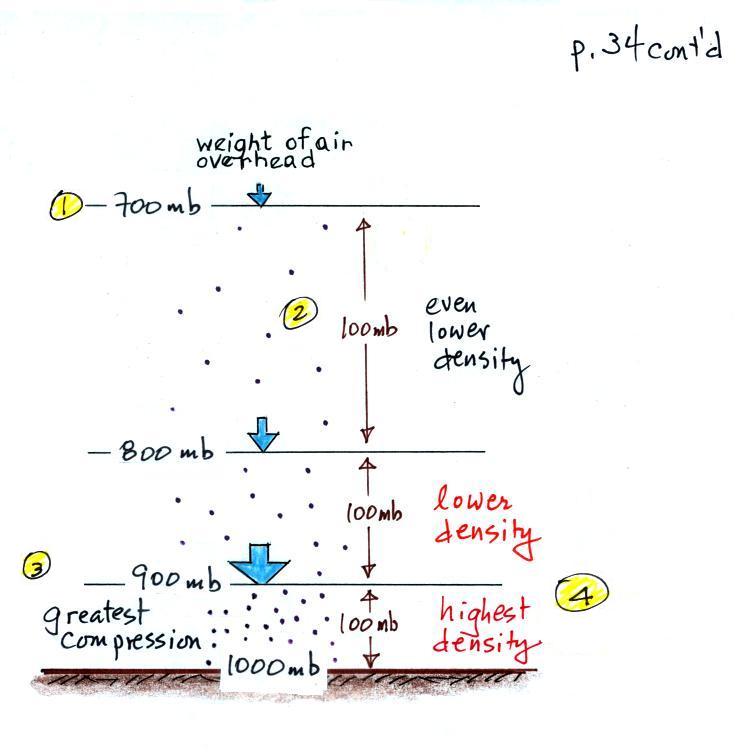

There's a surprising amount of information in this figure,

you need to spend a minute or two looking for it

1. You can first notice and remember that pressure

decreases with increasing altitude. 1000 mb at the

bottom decreases to 700 mb at the top of the picture. You

should be able to explain why this happens.

2. Each layer of air contains the same amount

(mass) of air. This is a fairly subtle point.

You can tell because the pressure drops by the same amount, 100

mb, as you move upward through each layer. Pressure depends

on weight. So if all the pressure changes are equal, the

weights of each of the layers must be the same. Each of the

layers must contain the same amount (mass) of air (each layer

contains 10% of the air in the atmosphere).

3. The densest air is found at the bottom of the picture.

The bottom layer is compressed the most because it is supporting

the weight of all of the rest of the atmosphere. It is the

thinnest layer in the picture and the layer with the smallest

volume. Since each layer has the same amount of air (same

mass) and the bottom layer has the smallest volume it must have

the highest density. The top layer has the same amount of

air but about twice the volume. It therefore has a lower

density (half the density of the air at sea level). Density

is decreasing with increasing altitude. That's the

main point in this figure.

4. A final point that you shouldn't worry too much about

yet. Pressure decreases 100 mb in a fairly short

vertical distance in the bottom layer of the picture - a rapid

rate of decrease with altitude. The same 100 mb drop takes

place in about twice the vertical distance in the top layer in the

picture - a smaller rate of decrease with altitude. Pressure

is decreasing most rapidly with increasing altitude in the

densest air in the bottom layer. We'll make use of

this concept again at the end of the semester when we try to

figure out why/how hurricanes intensify and get as strong as they

do.

Now on to the main topic of the day

and something I want to cover before the Experiment #1 reports are

due next Monday

Why does warm air rise and cold air sink?

Hot air balloons rise, so does the relatively warm air in a

thunderstorm updraft (it's warmer than the air around

it). Conversely cold air sinks. The surface

winds caused by a thunderstorm downdraft (as shown above) can

reach speeds of 100 MPH (stronger than most tornadoes) and are a

serious weather hazard that we'll come back to later in the

semester.

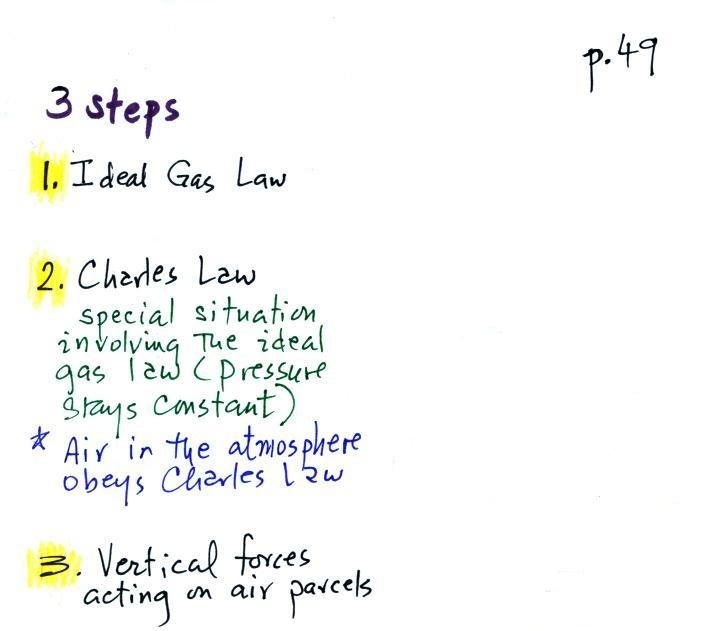

A full understanding of these rising and sinking motions is a

3-step process (the following is from the bottom part of p. 49

in the photocopied ClassNotes).

We will first learn about the

ideal gas law. It's is an equation that tells you

which properties of the air inside a balloon work to

determine the air's pressure. Then we will look at

Charles' Law, a special situation involving the ideal gas

law (air temperature volume, and density change together in

a way that keeps the pressure inside a balloon

constant). Then we'll learn about the 2 vertical

forces that act on air. I'm pretty sure you know what

the downward force is and am about equally sure you don't

remember what the upward force is (even though it is

something that has come up before in this class this

semester).

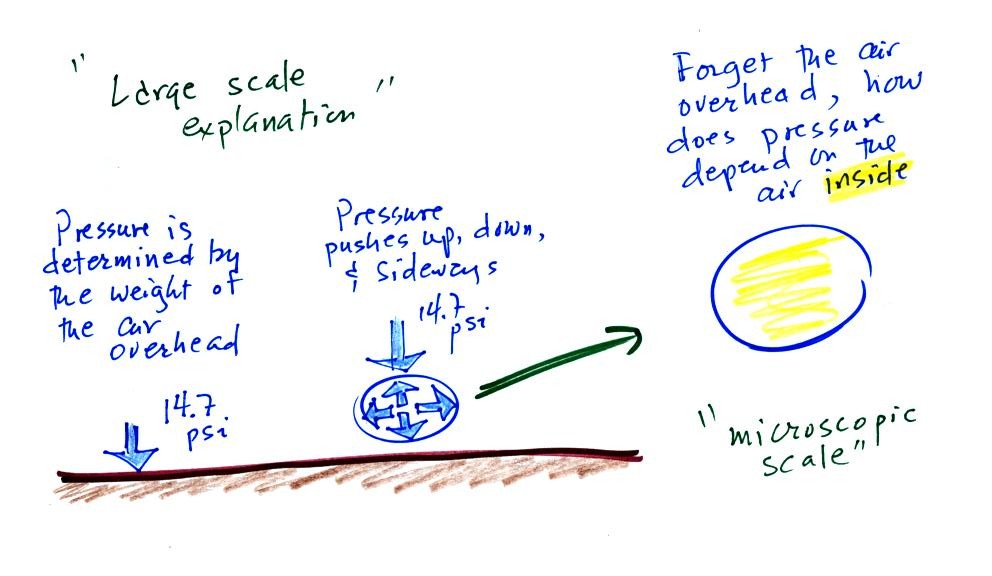

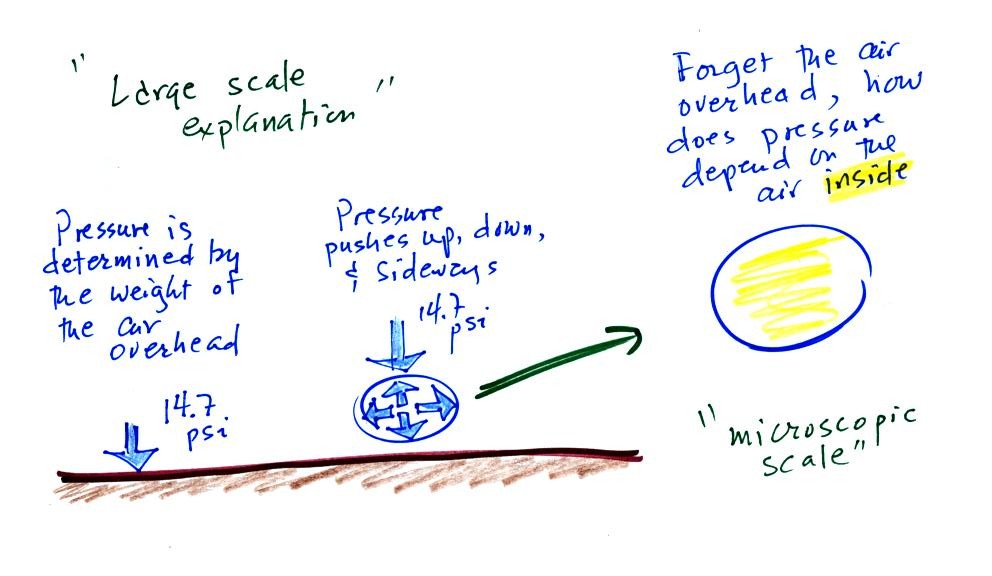

The ideal gas law - a microscopic scale explanation of air

pressure

We then went a bit further and tried to imagine the weight of

the atmosphere pushing down on a balloon sitting on the

ground. If you actually do push on a balloon you realize

that the air in the balloon pushes back with the same

force. Air pressure everywhere in the atmosphere pushes

upwards, downwards, and sideways.

These are large scale, atmosphere size, ways of thinking about

pressure. Next we are going to concentrate on just the

air in the balloon pictured above. This is more of a

microscopic view of pressure.

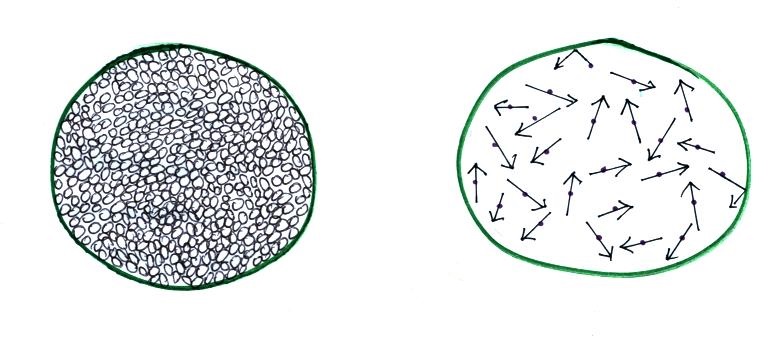

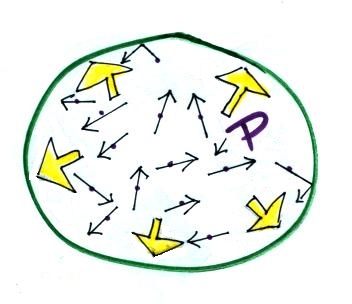

Imagine filling a balloon with air. If you could

look inside which picture below would be more realistic?

The view on the left is incorrect.

The air molecules actually do not fill the balloon and

take up all the available space.

|

This is the correct

representation.

The air molecules are moving

around at 100s of MPH but actually take up little or no

space in the balloon.

|

The air molecules are continually colliding

with the walls of the balloon and pushing outward (this force

divided by area is the pressure). Wikipedia

has a

nice animation. An individual molecule doesn't

exert a very strong force, but there are so many molecules

that the combined effect is significant.

We want to identify the properties or characteristics of the

air inside the balloon that determine the pressure and then put

them together into an equation called the ideal gas law

(actually there'll be two equations).

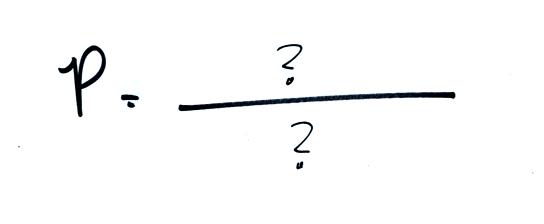

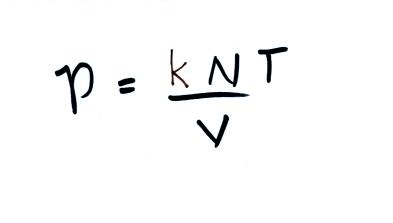

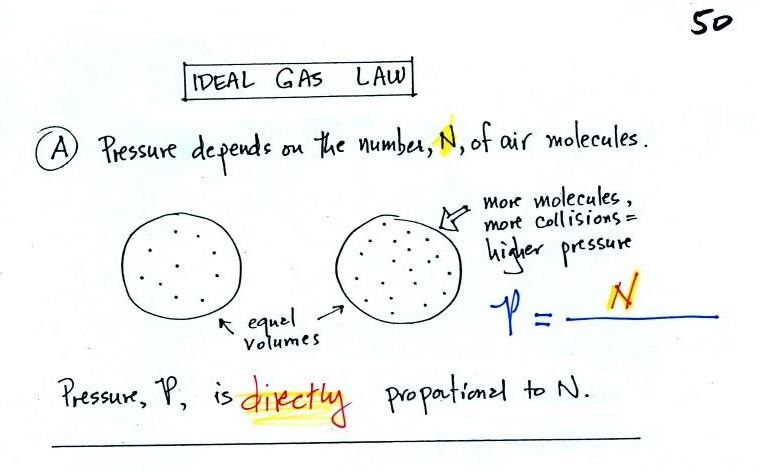

Step #1 The ideal gas law equation

You're not going to have to be able to figure out or remember

the ideal gas law equation. I'll give it to you. Here

is is:

You should know what the symbols in the equation

represent. Probably the most obvious variable is N the

number of air molecules. It's

the motions of the air molecules that produce pressure. No

air molecules (N = 0) means no pressure. The more air

molecules there are the higher the pressure.

Number of gas molecules or atoms

Pressure (P) is

directly proportional to Number of air molecules (N). If N

increases P increases and vice versa.

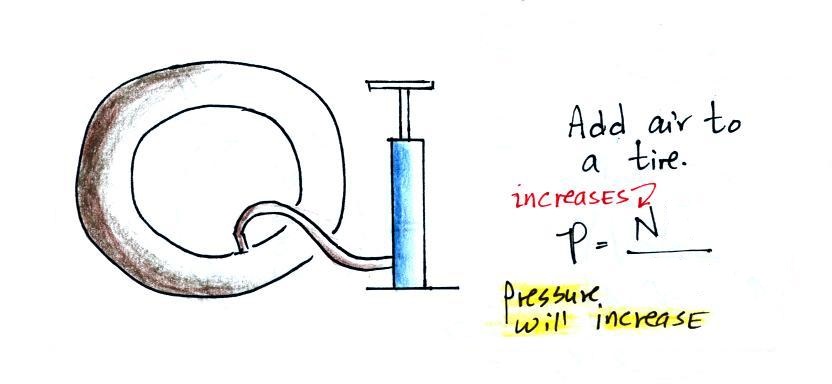

Here's an example. You're adding air

to a tire. As you add more and more air to something like a

bicycle tire, the pressure increases. Pressure is directly

proportional to N; an increase in N causes an increase in P.

If N doubles, P also doubles (as long as the other variables in

the equation don't change).

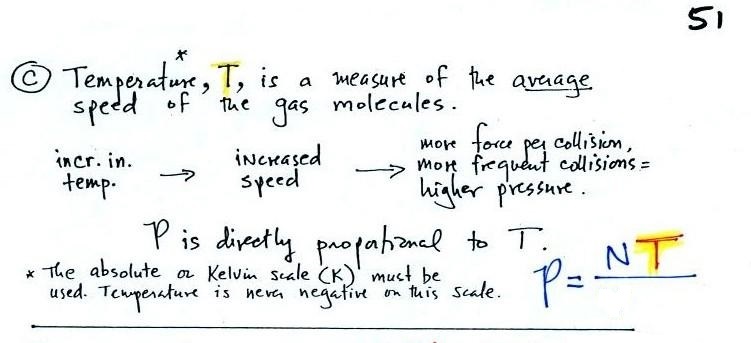

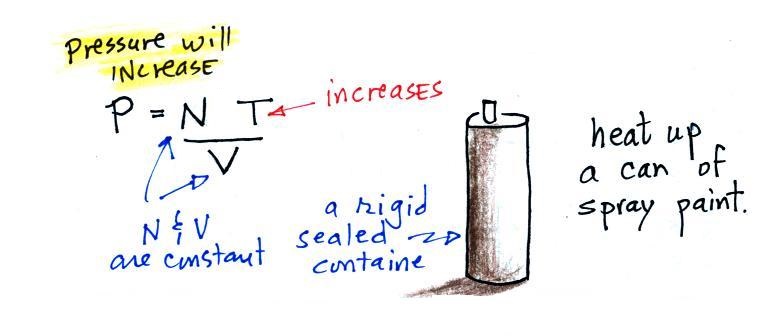

Temperature

Here's what I think is the next most obvious variable.

You shouldn't throw a

can of spray paint into a fire because the temperature

will cause the pressure of the gas (propellant) inside

the can to increase and the can could explode.

So T (temperature) belongs in the ideal gas law equation

Increasing the

temperature of the gas in a balloon will cause the gas

molecules to move more quickly (kind of like "Mexican

jumping beans"). They'll collide with the

walls of the balloon more frequently and rebound with

greater force - that will increase the pressure.

We've gotten a little bit ahead of the story. The

variable V (volume) has appeared in the equation and it's in the

denominator. A metal can is rigid. It's

volume can't change. When we start talking about volumes of

air in balloons or in the atmosphere volume can change. A

change in temperature or a change in number of air molecules might

be accompanied by a change in volume.

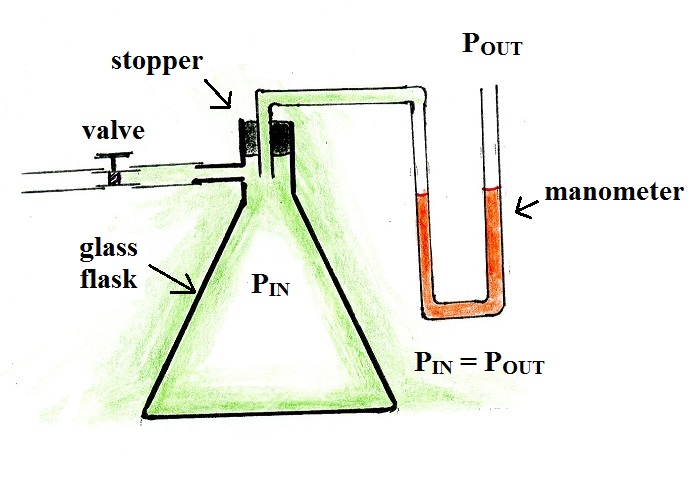

At this point we did a quick demonstration to show the effect

of temperature on the pressure of the gas in a rigid sealed

container (N and V in the ideal gas law equation stay constant,

just as in a can of spray paint). The description of the demonstration below

were added Tuesday morning, the day after class.

The container was a glass flask, sealed with a rubber

stopper. A piece of tubing with a valve was connected to the

flask. The valve was opened at the start of the

demonstration to be sure the pressures inside and outside the

flask were equal. The valve was then closed. The

manometer is a U-shaped tube filled with a liquid (transmission

oil) that can detect differences in pressure. Pressure from

the air inside the flask could enter one end of the manometer

tube. The other end was exposed to the pressure of the air

outside the flask.

Green in the figure indicates that the temperatures of the air

inside and outside the flask were equal. The manometer is

showing that the pressure of the air inside and outside the flask

were equal.

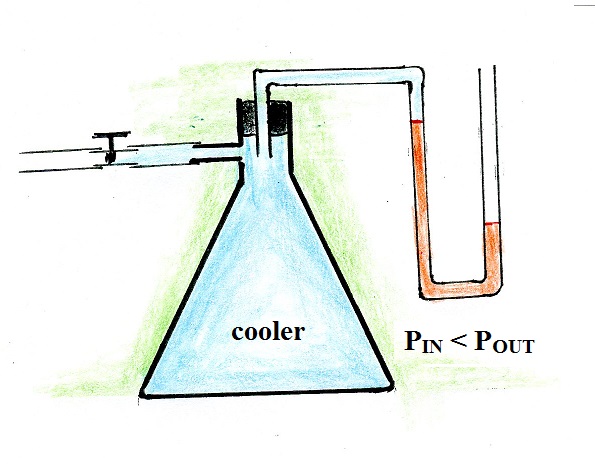

I wrapped my hands around the flask to warm the air inside very

slightly. The increase in air temperature caused a slight

increase in the pressure of the air inside the flask. The

air outside didn't change. Note the change in the levels of

the liquid in the manometer indicating the increase of the air

pressure inside the flask.

The valve was opened momentarily so that the pressures inside

and out would again be equal. The valve was then closed and

some isopropyl alcohol (rubbing alcohol) was dribbled on the

outside of the flask. As the alcohol evaporated it cooled

the flask and the air inside the flask. This caused the air

pressure inside the flask to drop. This change in air

pressure was again indicated by the liquid levels in the

manometer.

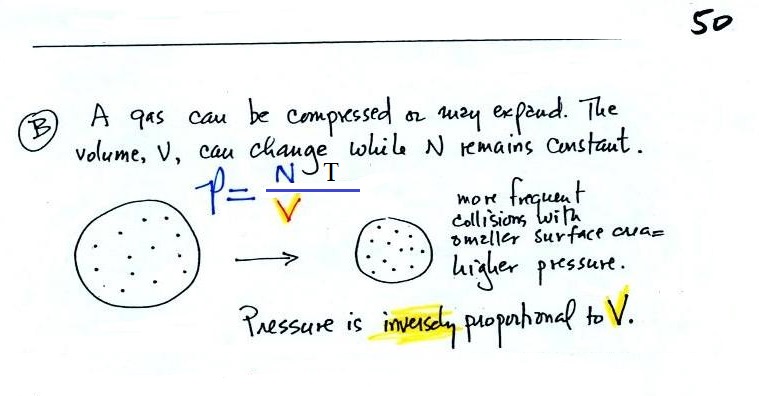

Volume

The effect of volume on pressure might be a little harder to

understand. Just barely fill a balloon with air, wrap your

hands around it, and squeeze it. It's hard and you don't

compress the balloon very much at all.

Or think of the bottom layer of the atmosphere

being squished by the weight of the air above. As the

bottom layer is compressed and its volume shrinks it pushes

back with enough force to eventually support the air above.

A decrease in volume

causes an increase in pressure, that's an inverse

proportionality.

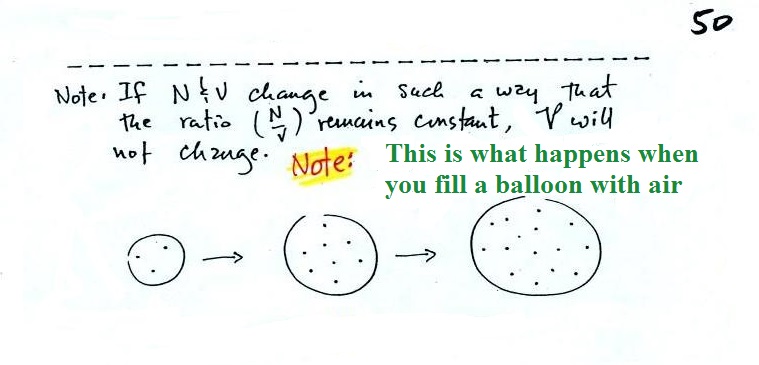

It might take three or four

breaths of air to fill a balloon. Think about

that. You add some air (N increases) and the balloon

starts to inflate (V increases). Then you add another

breath of air. N increases some more and the balloon

gets a little bigger, V has increased again. As you

fill a balloon N and V are both increasing. What is

happening in this case is that the pressure of the air in

the balloon is staying constant. The

pressure inside the balloon pushing outward and trying to

expand the balloon is staying

equal to (in balance with) the pressure of the air outside

pushing inward and trying to compress the balloon.

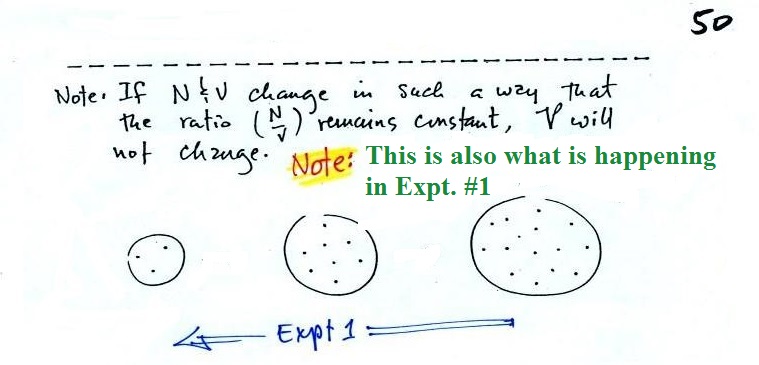

Here's the same picture again except N and V

are decreasing together in a way that keeps pressure

constant. This is exactly what is happening in Experiment

#1.

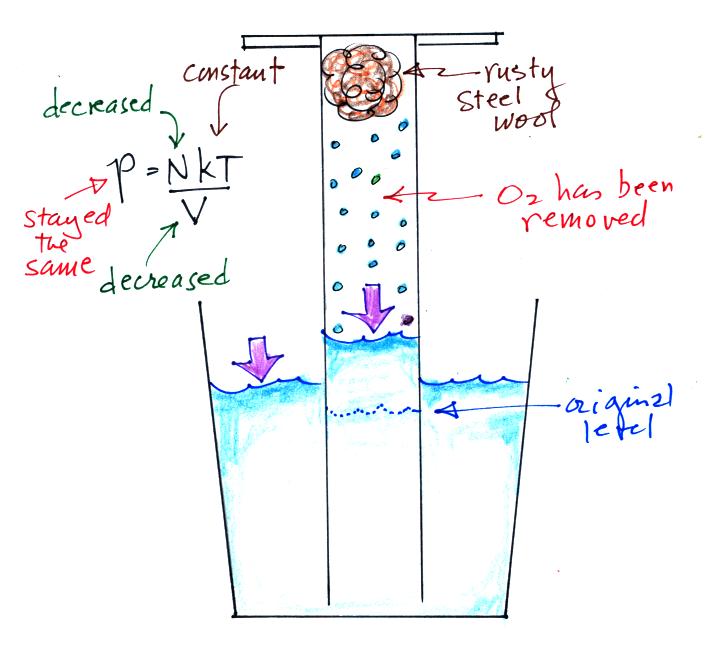

Experiment #1

- P stays constant, N & V both decrease

Here's a little more detailed explanation of Expt. #1

|

|

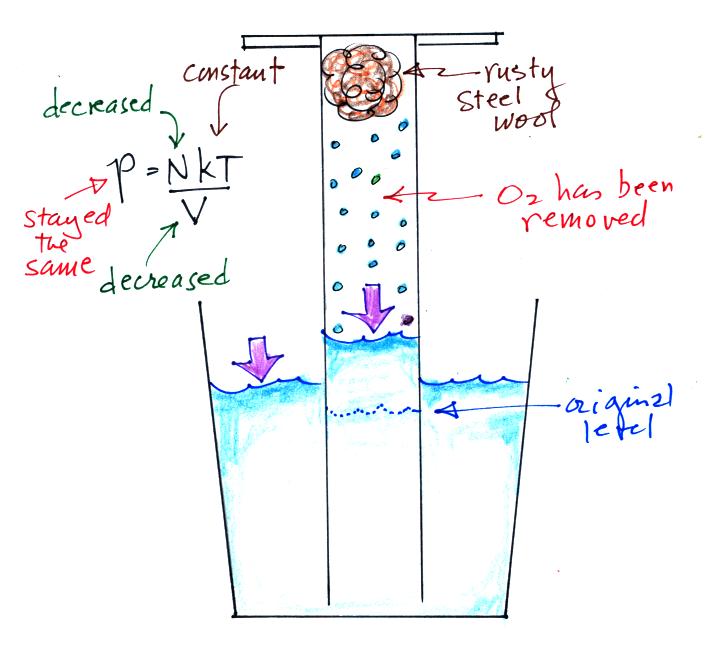

The object of Experiment #1

is to measure the percentage concentration

of oxygen in the air. An

air sample is trapped together with some steel wool

inside a graduated cylinder. The cylinder is

turned upside down and the open end is stuck into a

glass of water sealing off the air sample from the rest

of the atmosphere. This is shown at left

above. The pressure of air outside the cylinder

tries to push water into the cylinder, the pressure of

the air inside keeps the water out.

Oxygen in the cylinder reacts with

steel wool to form rust. Oxygen is removed from

the air sample which causes N (the total number of air

molecules) to decrease. Removal of oxygen would

ordinarily cause a drop in Pin

and

upset the balance between Pin

and Pout

. But, as oxygen

is removed, water rises up into the cylinder decreasing

the air sample volume. The decrease in V is what

keeps Pin

equal to Pout

.

N and V both decrease together in the same relative

amounts and the air sample pressure remains constant.

If you were to remove 20% of the air molecules, V would

decrease to 20% of its original value and pressure would stay

constant. It is the change in V that you can see, measure,

and use to determine the oxygen percentage concentration in

air. You should try to explain this in your experiment

report.

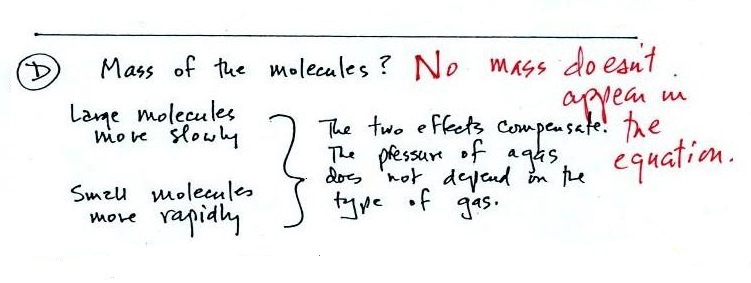

You might think that the mass of the gas molecules inside a

balloon might affect the pressure (big atoms or molecules might

hit the walls of the balloon harder and cause higher pressure

and vice versa).

The mass of the air molecules doesn't matter. The big ones

move relatively slowly, the smaller ones more quickly.

They both hit the walls of the balloon with the same

force. A variable for mass doesn't appear in

the ideal gas law equation.

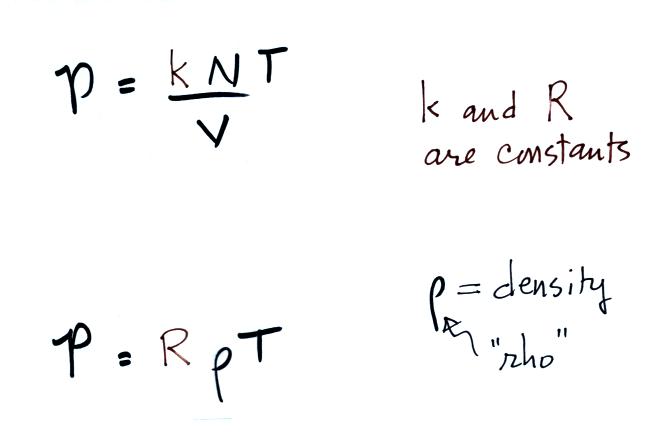

The figure below shows two forms of the ideal

gas law. The top equation is the one we've been looking at

and the bottom is a second slightly different version. You

can ignore the constants k and R if you are just trying to

understand how a change in one of the variables would affect the

pressure. You only need the constants when you are doing a

calculation involving numbers and units (which we won't be

doing).

The ratio N/V is similar to density

(mass/volume). That's where the ρ (density)

term in the second equation comes from.