Friday Feb. 26, 2016

Eva Cassidy "American Tune"

(4:09), Crooked Still "American Tune"

(3:25), Black Prairie "Nowhere

Massachusetts" (3:20), Punch Brothers "Sometimes"

(4:57)

An In-class

Optional Assignment was handed out today and collected at

the end of class. If you weren't in class and would like to

do the assignment you can download using the link at left.

If you turn in the assignment at the beginning of class next

Monday you will receive at least partial credit (as with all

Optional Assignments you should have the assignment done before

coming to class).

Energy transport by electromagnetic

radiation

It's time to tackle electromagnetic (EM)

radiation, the 4th and most important of the energy transport

processes (it's the most important because it can transport

energy through empty space (outer space)).

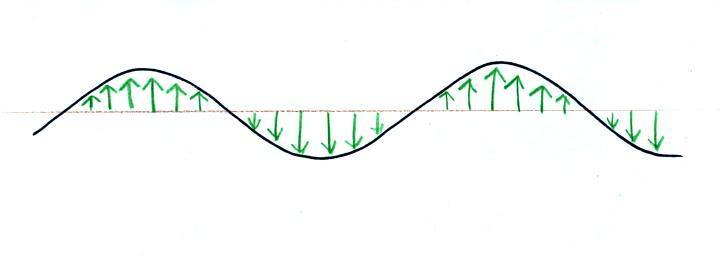

Many introductory textbooks depict EM

radiation with a wavy line like shown above. They don't

usually explain what the wavy line represents.

The wavy line just connects the tips of a

bunch of "electric field arrows". But what exactly are electric

field arrows?

Static electricity and electric fields

To understand electric

fields we need to first step back and review a

couple of rules concerning static electricity.

That won't take too long, static

electricity is something you're most likely already familiar

with.

Believe it or not there is even a National Static

Electricity Day (Jan. 9).

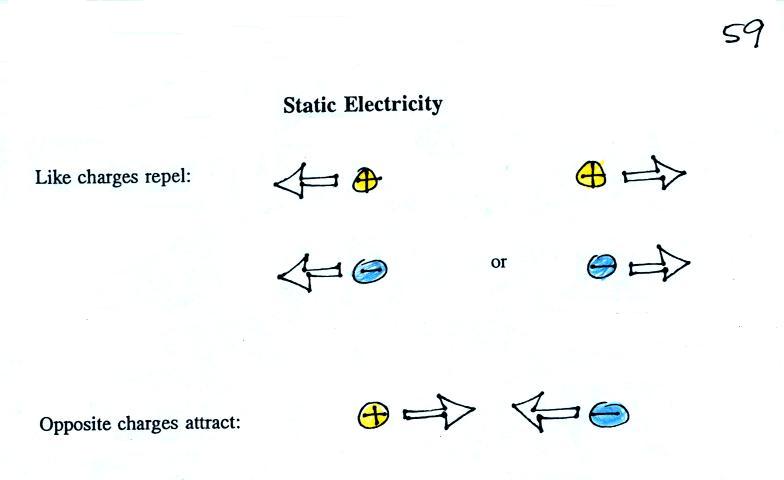

The static

electricity rules are found at the top of p. 59 in the

photocopied ClassNotes

Two electrical charges with the same polarity (two positive

charges or two negative charges) push each other apart.

Opposite charges are attracted to each other.

Here

are some pictures I found online.

|

|

This girl became charged with static

electricity while jumping on a trampoline and

illustrates the repulsive force of like charges.

Her hair and body are all charged up with charge of the

same polarity. The individual hairs are trying to

get as far away from each other as they can. This

photo was a National Geographic Magazine 2013

Photo Contest winner (source)

People's hair will sometimes stand on end

under a thunderstorm. That is a very dangerous

situation to be in.

|

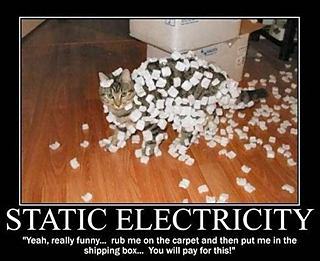

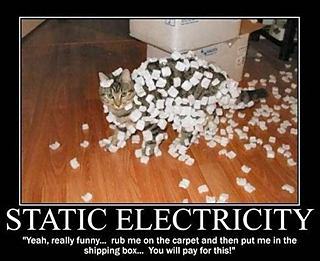

A cat covered in Styrofoam

"peanuts". Here the cat and the

"peanuts" have opposite charges and are attracted

to each other. (source)

Being a cat owner I would worry about the cat

swallowing one of the peanuts and possibly choking.

|

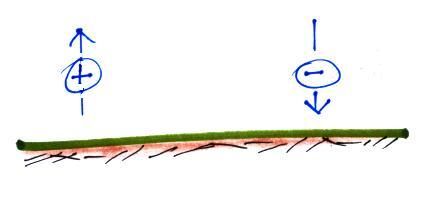

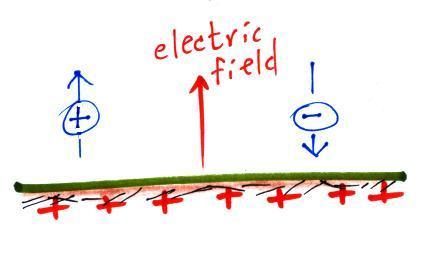

An electric

field arrow (vector)

just shows the direction

and

gives you an idea of the strength

of the electrical force

that would be exerted on a positive

charge at that position.

It's just like an arrow painted on a drive showing you what

direction to drive.

Here are a couple of questions to test your

understanding.

First what polarity of charge must be on ground to cause the

charges in the figure below to move as they are doing.

Would the electric field arrow in the air just above the ground

point UPWARD, point DOWNWARD, or would the electric field arrow be

ZERO?

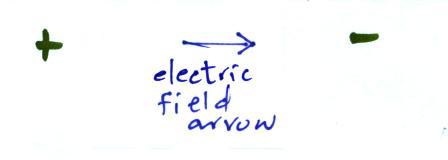

Here's a second perhaps somewhat harder question

What is the direction of the electric field arrow at Point X halfway between a +

and a - charge.

You'll find answers to both questions at the end of today's notes.

Electromagnetic (EM) radiation

Now we'll use what we know about electric field arrows (electric

field for short) to start to understand electromagnetic

radiation. How is it able to carry energy from

one place to another. You'll find most of the following on

p. 60 in the photocopied ClassNotes.

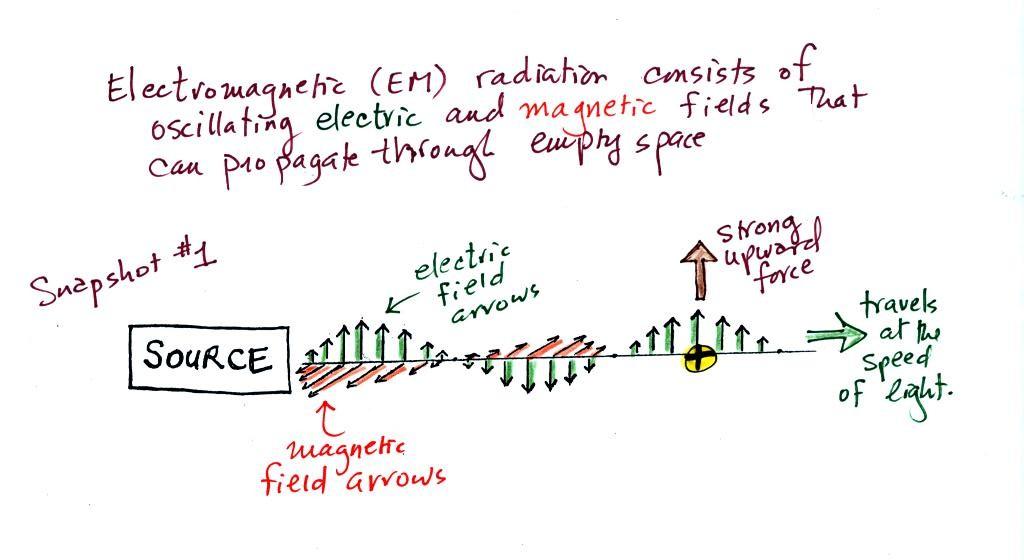

We imagine turning on a source of EM radiation and then a

very short time later we take a snapshot. In that time the

EM radiation has traveled to the right (at the speed of

light). The EM radiation is a wavy pattern of electric and

magnetic field arrows. We'll ignore the

magnetic field arrows. The E field arrows sometimes point

up, sometimes down. The pattern of electric field arrows

repeats itself.

Note the + charge near

the right side of the picture. At the time this picture

was taken the EM radiation exerts a fairly strong upward force

on the + charge (we use

the E field arrow at the location of the + charge to determine the

direction and strength of the force exerted on the + charge).

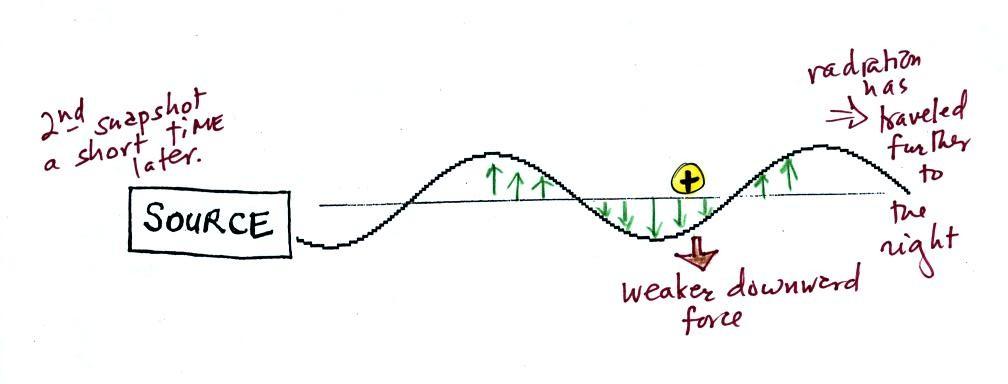

This picture above was taken a short time after the first

snapshot after the radiation had traveled a little further to

the right. The EM radiation now exerts a somewhat weaker

downward force on the +

charge.

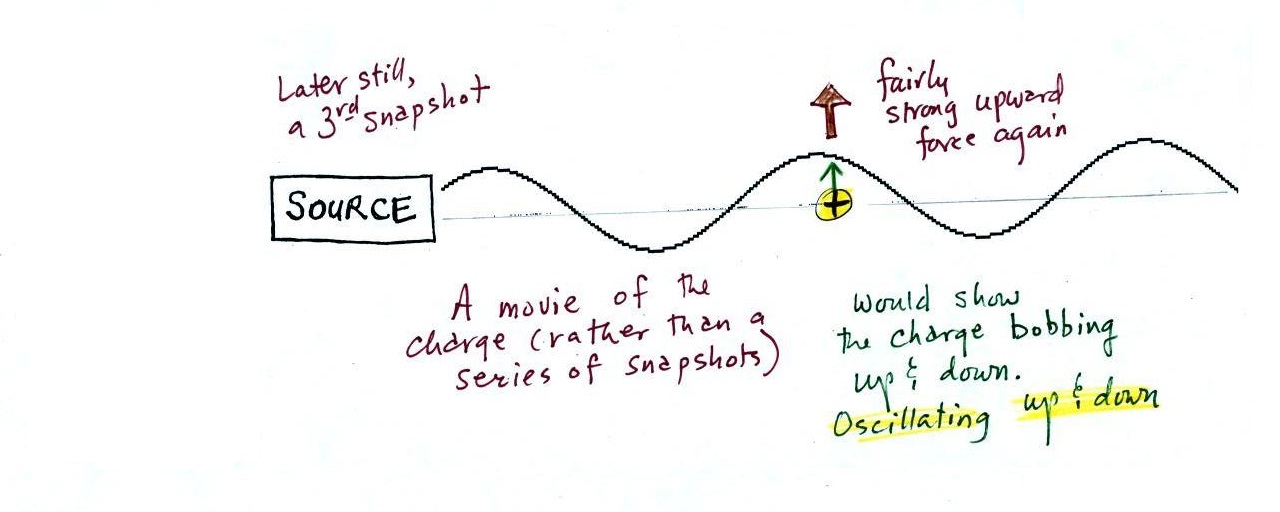

A 3rd snapshot taken a short time later. The + charge is now being pushed

upward again.

A movie of the + charge,

rather than just a series of snapshots, would show the charge

bobbing up and down much like a swimmer in the ocean would do as

waves passed by.

Wavelength and frequency

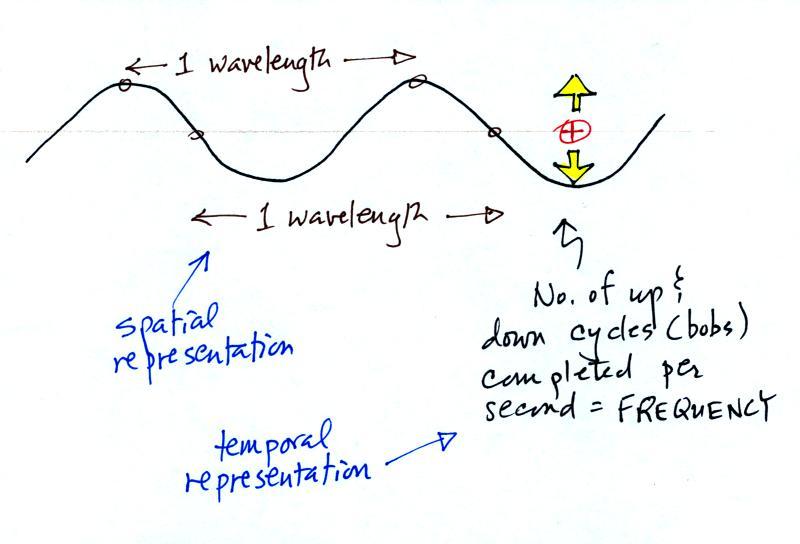

The wavy pattern used to depict EM radiation can be

described spatially

(what you would see in a snapshot) in terms of its wavelength,

the distance between identical points on the pattern.

Or you can describe the radiation temporally

using the frequency of oscillation (number of up and down cycles

completed by an oscillating charge per second). By

temporally we mean you look at one particular fixed point and

look at how things change with time.

Wavelength, frequency, and energy

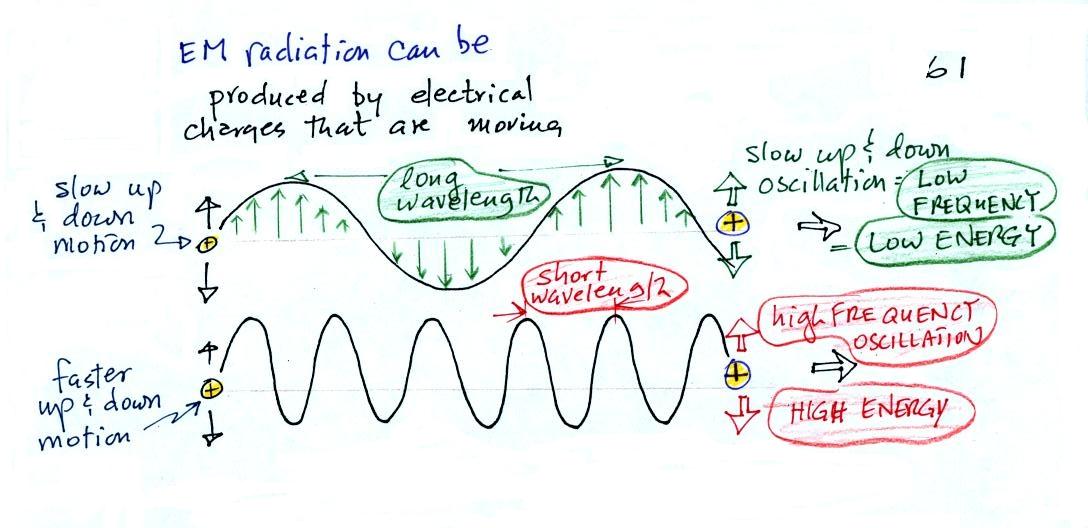

EM radiation can be created when you cause a charge to

move up and down. If you move a charge up and down

slowly (upper left in the figure above) you would produce long

wavelength radiation that would propagate out to the right at the

speed of light. If you move the charge up and down more

rapidly you produce short wavelength radiation that propagates at

the same speed.

Once the EM radiation encounters the charges at the right side

of the figure above the EM radiation causes those charges to

oscillate up and down. In the case of the long wavelength

radiation the charge at right oscillates slowly. This is low

frequency and low energy motion. The short wavelength causes

the charge at right to oscillate more rapidly - high frequency and

high energy.

These three characteristics: long

wavelength / low frequency / low energy go

together. So do short wavelength / high

frequency / high energy. Note that the two

different types of radiation both propagate at the same speed.

The

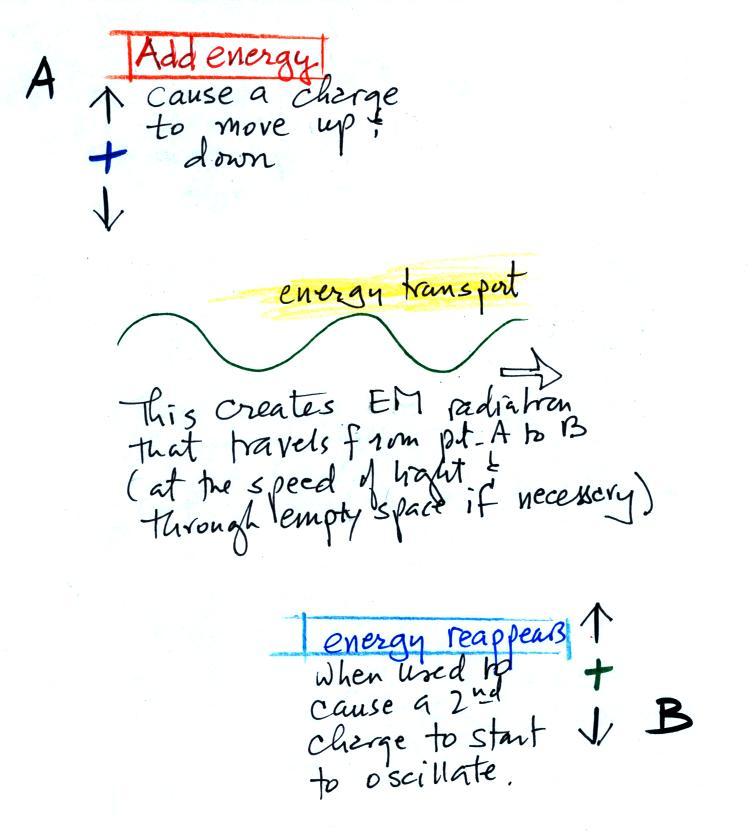

following figure illustrates how energy can be transported

from one place to another (even through empty space) in the

form of electromagnetic (EM) radiation.

You add energy when you cause an

electrical charge to move up and down and create the EM

radiation (top left).

In the middle figure, the EM

radiation that is produced then travels out to the right (it

could be through empty space or through something like the

atmosphere).

Once the EM radiation encounters an electrical charge at

another location (bottom right), the energy reappears as the

radiation causes the charge to move. Energy has been

transported from left to right.

The electromagnetic spectrum

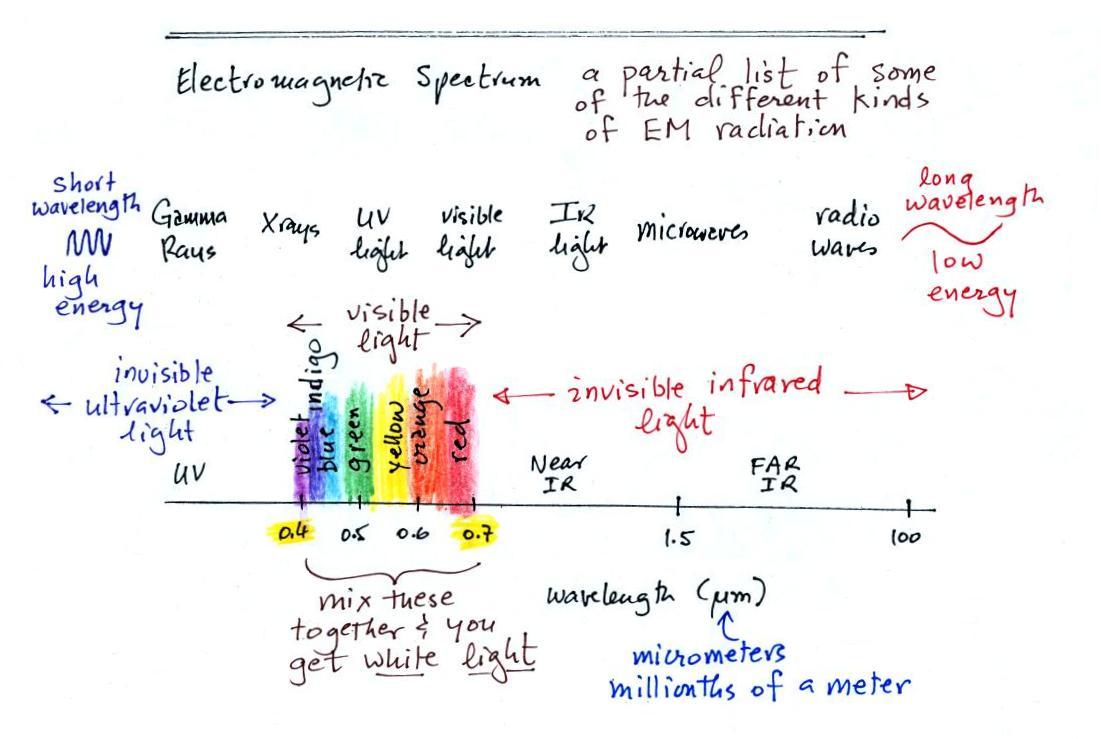

The EM spectrum is just a list of the different kinds of EM

radiation. A partial list is shown below.

In the top list, shortwave wavelength/high energy forms of EM

radiation are on the left (gamma rays and X-rays for

example). Microwaves and radiowaves are longer

wavelength/lower energy forms of EM radiation.

We will mostly be concerned with just ultraviolet light (UV),

visible light (VIS), and infrared light (IR). These are

shown on an expanded scale below. Note the micrometer

(millionths of a meter) units used for wavelength for these kinds

of light. The

visible portion of the spectrum falls between 0.4 and 0.7

micrometers. UV and IR light are both

invisible. All of the vivid colors shown above are just EM

radiation with slightly different wavelengths. When you see

all of these colors mixed together, you see white light.

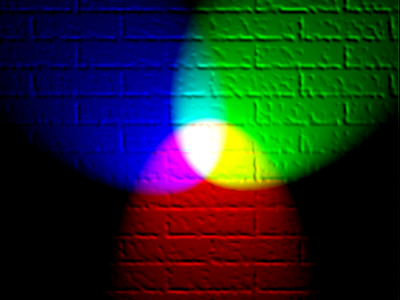

I've tried to demonstrate colors mixing together to make white

light using laser pointers.

But it's too hard to get them adjusted so that the small spots

of colored light all fall on top of each other on the screen at

the front of the room. And even if you do the small spot of

light is so small that it's hard to see clearly in a large

classroom (you need to do the experiment on a piece of paper a few

feet away).

Here's the basic idea, you mix red green and blue light

together. You see white light were the three colors overlap

and mix in the center of the picture above.

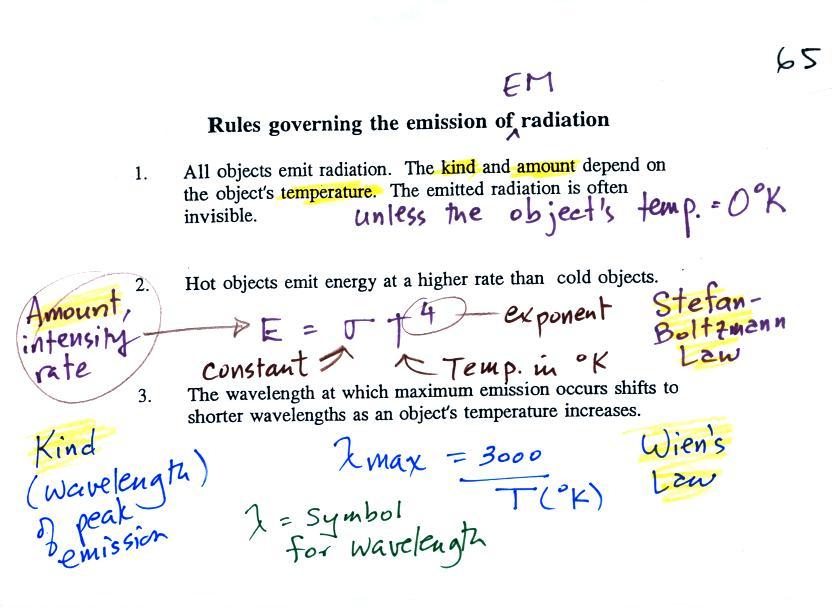

Rules governing the

emission of EM radiation

We spent most of the rest of

the class learning about some rules governing the emission of

electromagnetic radiation. Here they are:

1.

Everything

warmer than 0 K will emit EM radiation. Everything in

the classroom: the people, the furniture, the walls and the

floor, even the air, are emitting EM radiation.

Often this radiation will be invisible so that we can't see it

and weak enough that we can't feel it (or perhaps because it

is always there we've grown accustomed to it and ignore

it). Both the amount and kind (wavelength) of the

emitted radiation depend on the object's temperature. In

the classroom most everything has a temperature of around 300

K and we will see that means everything is emitting infrared

(IR) radiation with a wavelength of about 10µm.

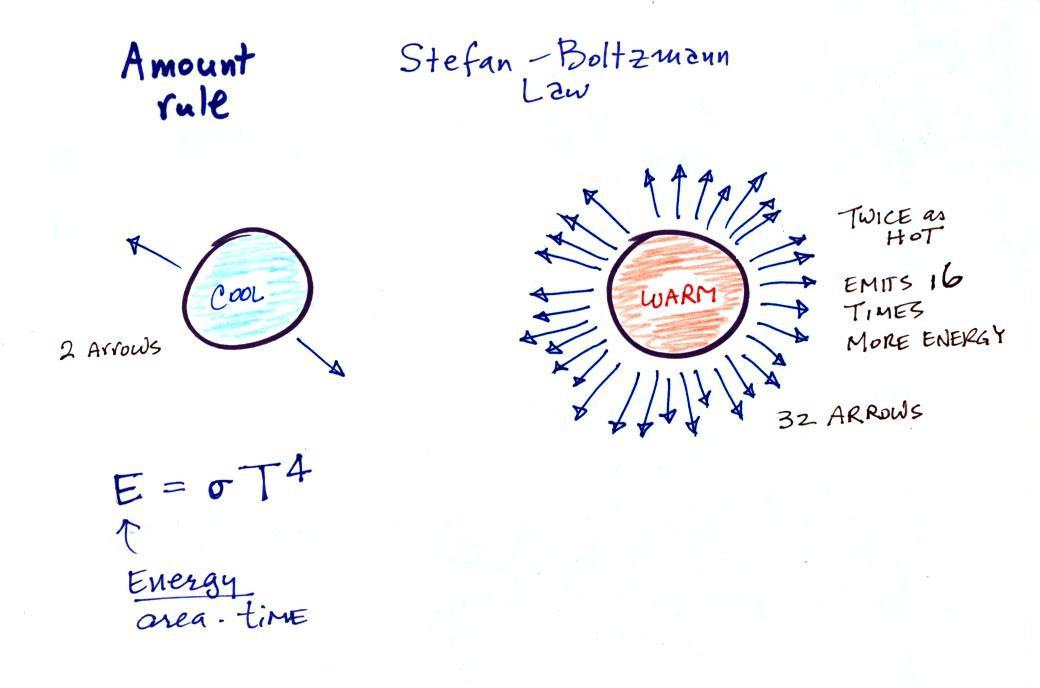

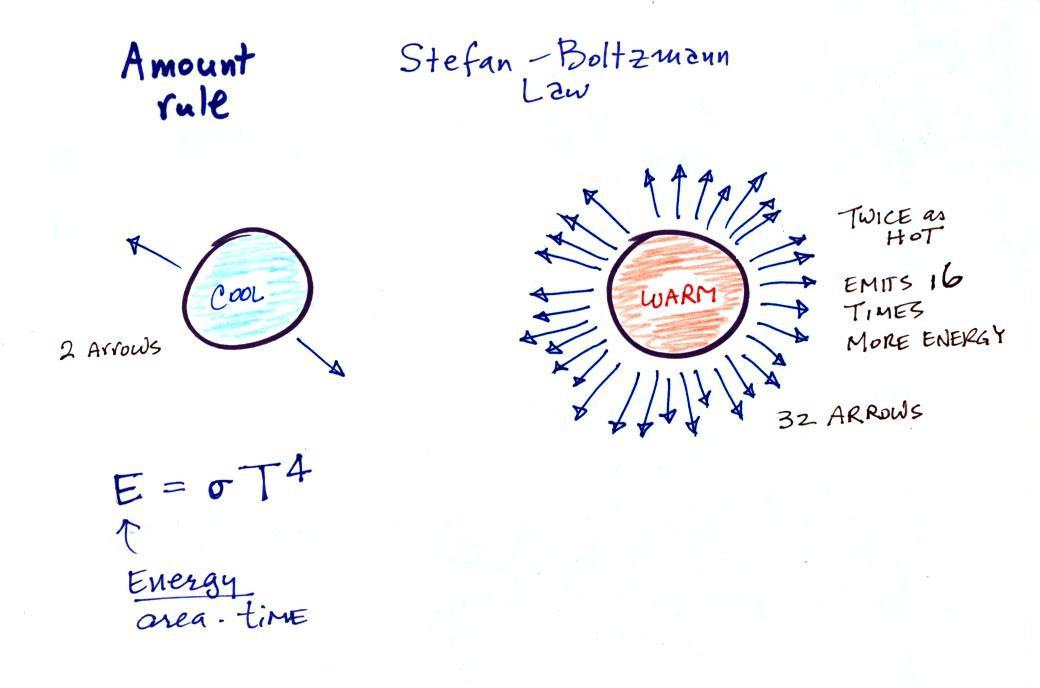

2.

The second rule allows you to determine the

amount of EM radiation (radiant energy) an object will

emit. Don't worry about the units (though they're given

in the figure below), you can think of this as amount, or

rate, or intensity. Don't worry about σ (the Greek character rho) either, it is

just a constant. The amount depends

on temperature to the fourth power. If the temperature

of an object doubles the amount of energy emitted will

increase by a factor of 2 to the 4th power (that's 2 x 2 x 2 x

2 = 16). A hot object just doesn't emit a little more

energy than a cold object it emits a lot more energy than a

cold object. This is illustrated in the following

figure:

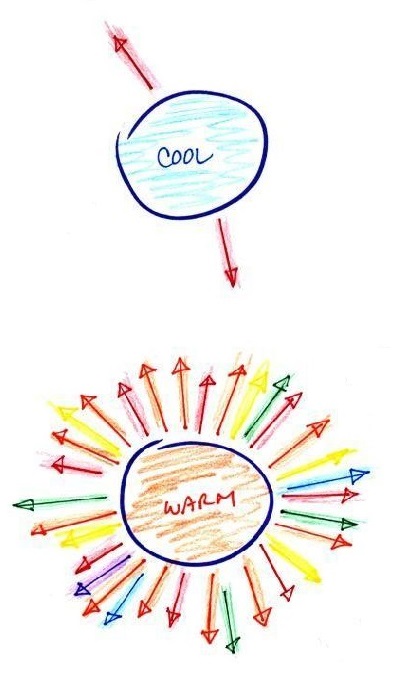

The cool object is emitting 2

arrows worth of energy. This could be the earth at 300

K. The warmer object is 2 times warmer, the earth heated

to 600 K. The earth then would emit 32 arrows (16 times

more energy).

The earth has a temperature of 300 K. The sun is 20

times hotter (6000 K). Every square foot of the sun's

surface will emit 204 (160,000)

times more energy per second than a square foot of the

earth's surface.

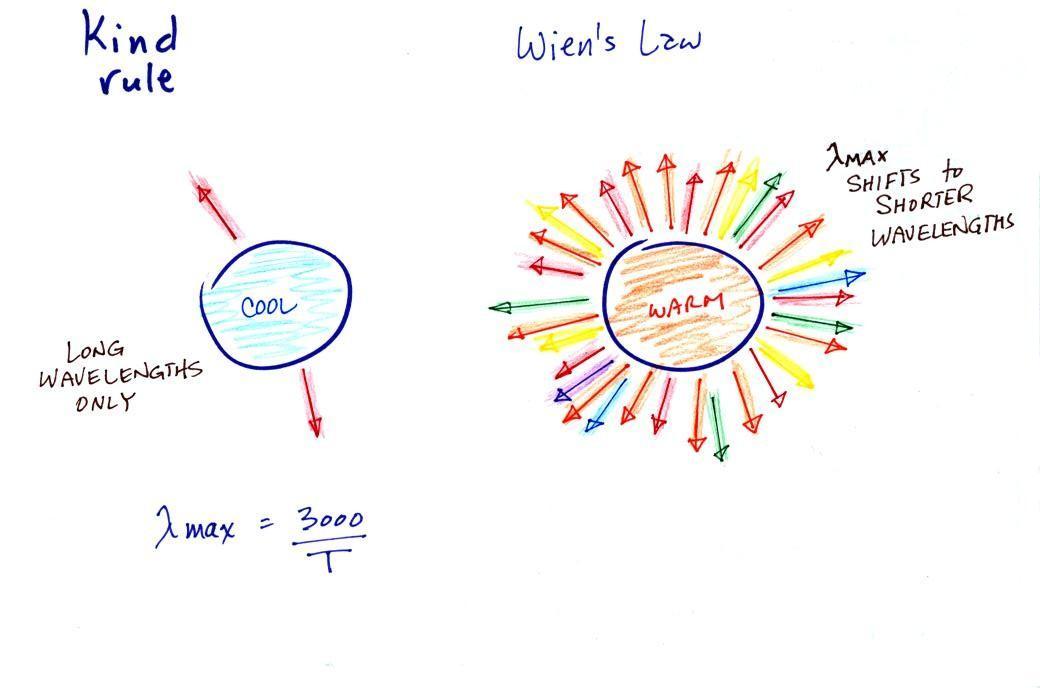

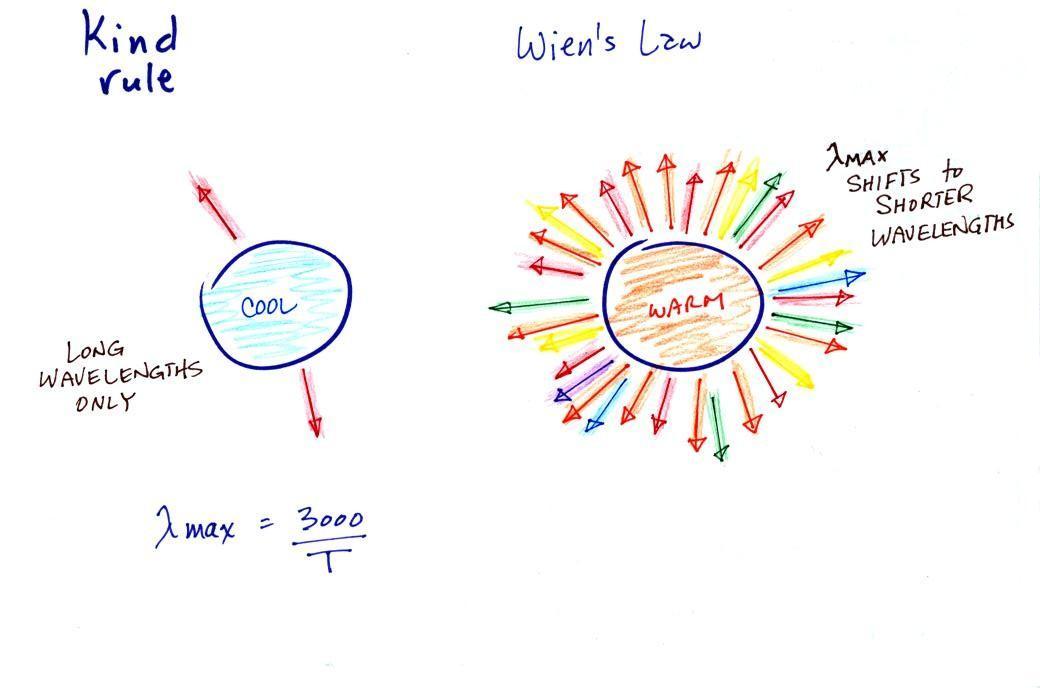

3.

The third rule tells you something about the kind of

radiation emitted by an object. We will see that objects

usually emit radiation at many different wavelengths but not in

equal amounts. Objects emit more of one particular

wavelength than any of the others. This is called λmax

("lambda max", lambda is the Greek character used to represent

wavelength) and is the wavelength of maximum emission. The

third rule allows you to calculate λmax.

The tendency for warm objects to emit radiation at shorter

wavelengths is shown below.

The cool object could be emitting infrared light

(that would be the case for the earth at 300 K). It might be

emitting a little bit of red light that we could see. That's

the 2 arrows of energy that are colored red. The warmer

object will also emit IR light but also shorter wavelengths such

as yellow, green, blue, and violet (maybe even some UV if it's hot

enough). Remember though when

you start mixing different colors of visible light you get

something that starts to look white. The cool object

might appear to glow red, the hotter object would be much

brighter and would appear white.

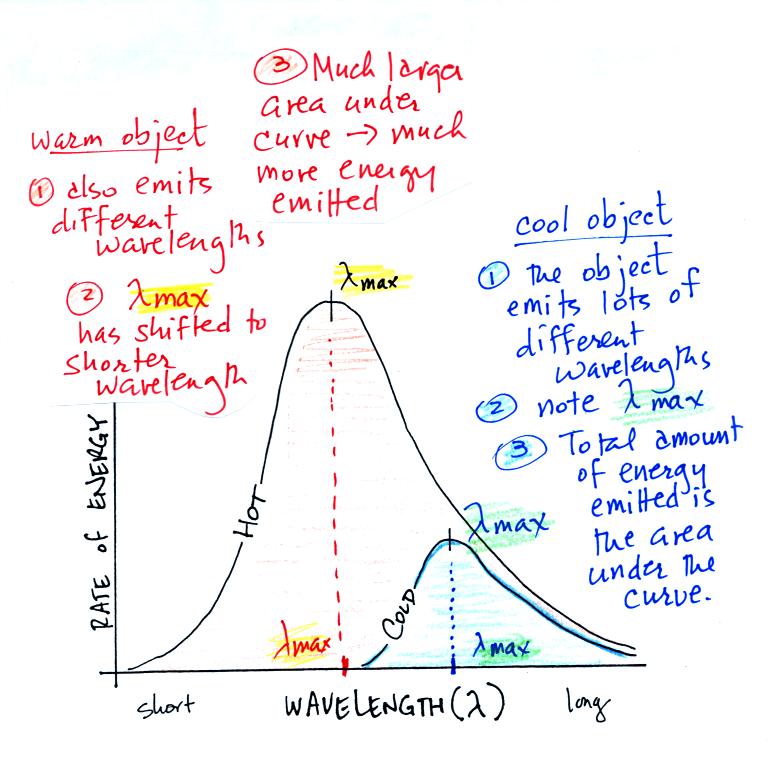

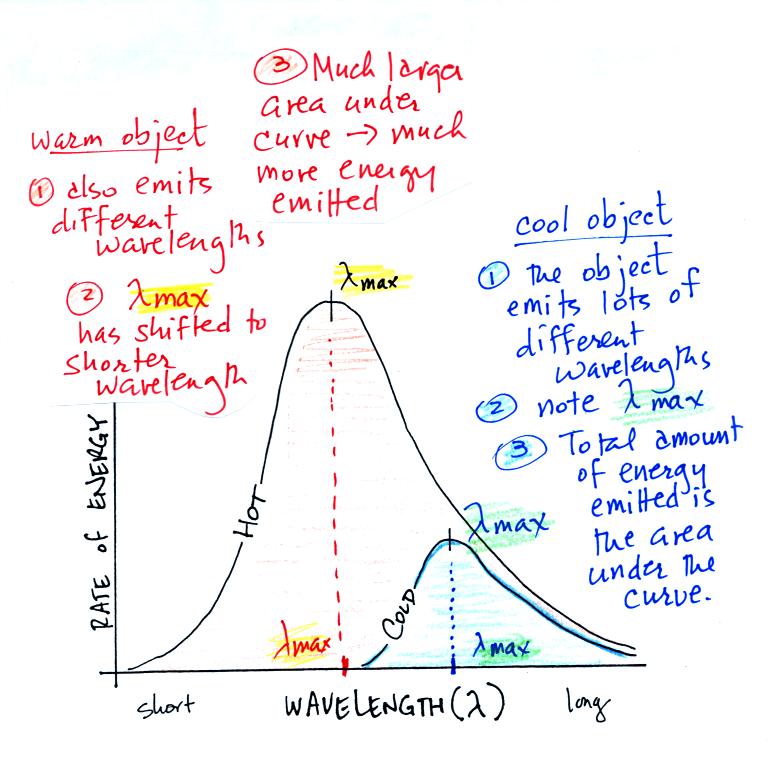

Here's another way of understanding Stefan Boltzmann's law and

Wien's Law (the graph

below is on the bottom of p. 65 in the ClassNotes).

1.

Notice

first that both and warm and the cold objects emit radiation

over a range of wavelengths (the curves above are like quiz

scores, not everyone gets the same score, there is a

distribution of grades). The warm object emits all the

wavelengths the cooler object does plus lots of additional

shorter wavelengths.

2.

The peak of

each curve is λmax

the wavelength of peak emission (the

object emits more of that particular wavelength than any other

wavelength). Note that λmax

has shifted toward shorter wavelengths for the warmer

object. That is Wien's law in action. The warmer

object is emitting lots of types of short wavelength radiation

that the colder object doesn't emit.

3.

The area under the curve is the total radiant

energy emitted by the object. The area

under the warm object curve is much bigger than the area

under the cold object curve. This

illustrates the fact that the warmer object emits a lot more

radiant energy than the colder object.

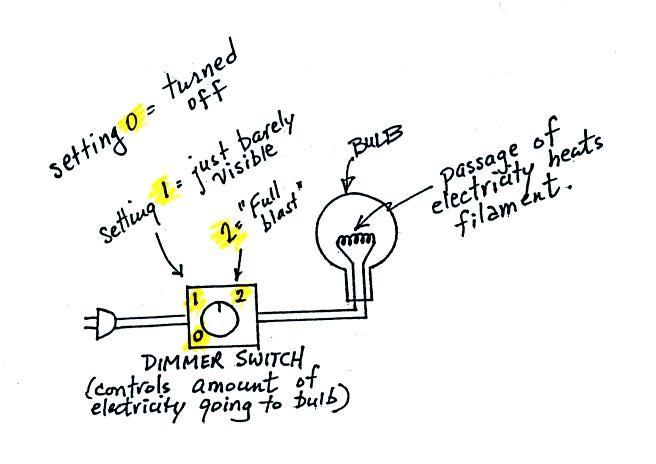

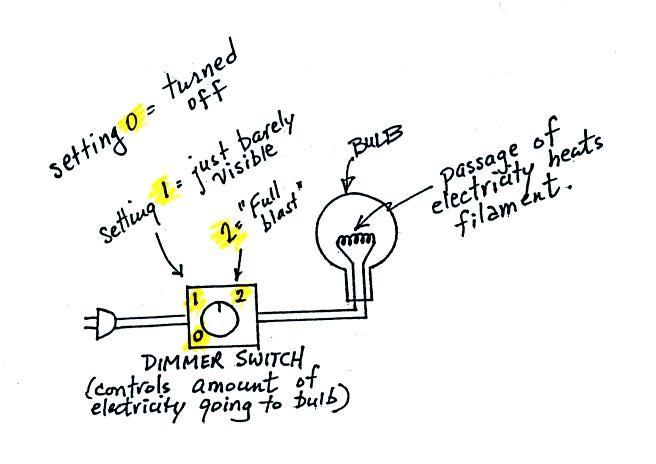

It is relatively easy to see Stefan-Boltzmann's law and Wien's

Law in action. The class demonstration consisted of an

ordinary 200 W tungsten bulb is connected to a dimmer switch (see

p. 66 in the photocopied ClassNotes). We'll be looking at

the EM radiation emitted by the bulb filament.

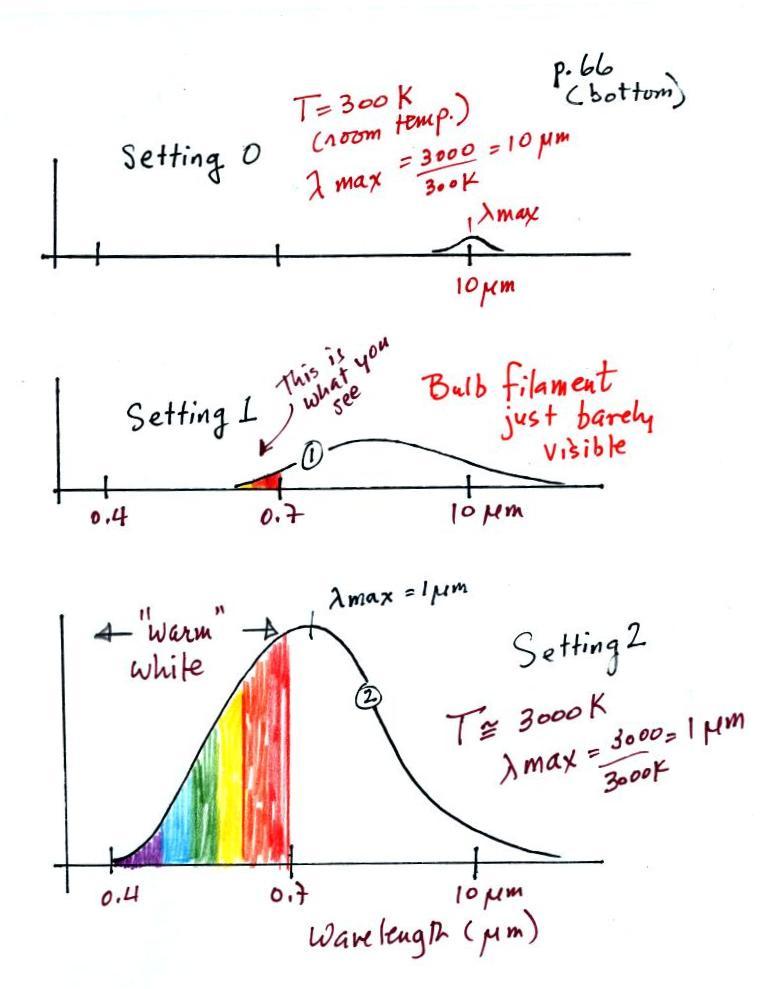

The graph at the bottom of p. 66

has been split up into 3 parts and redrawn for improved clarity.

We start with the bulb turned off (Setting 0). The

filament will be at room temperature which we will assume is

around 300 K (remember that is a reasonable and easy to remember

value for the average temperature of the earth's surface).

The bulb will be emitting radiation, it's shown on the top graph

above. The radiation is very weak so we can't feel

it. We can use Wien's Law to calculate the

wavelength of peak emission, λmax

. The wavelength of peak emission

is 10 micrometers which is long wavelength, far IR radiation so we can't

see it.

Next we use the dimmer switch to just barely turn the bulb on

(the temperature of the filament is now about 900 K). The

bulb wasn't very bright at all and had an orange color.

This is curve 1, the middle figure. Note the far left end

of the emission curve has moved left of the 0.7 micrometer mark

- into the visible portion of the spectrum. That is what

you were able to see, just the small fraction of the radiation

emitted by the bulb that is visible light (but just long

wavelength red and orange light). Most of the radiation

emitted by the bulb is to the right of the 0.7 micrometer mark

and is invisible IR radiation (it is strong enough now that you

could feel it if you put your hand next to the bulb).

Finally we turn on the bulb completely (it is a 200 Watt bulb

so it got pretty bright). The filament temperature is now

about 3000K. The bulb is emitting a lot more visible

light, all the colors, though not all in equal amounts.

The mixture of the colors produces a "warm white" light.

It is warm because it is a mixture that contains a lot more red,

orange, and yellow than blue, green, and violet light. It

is interesting that most of the radiation emitted by the bulb is

still in the IR portion of the spectrum (lambda max is 1

micrometer). This is invisible light. A tungsten

bulb like this is not especially efficient, at least not as a

source of visible light.

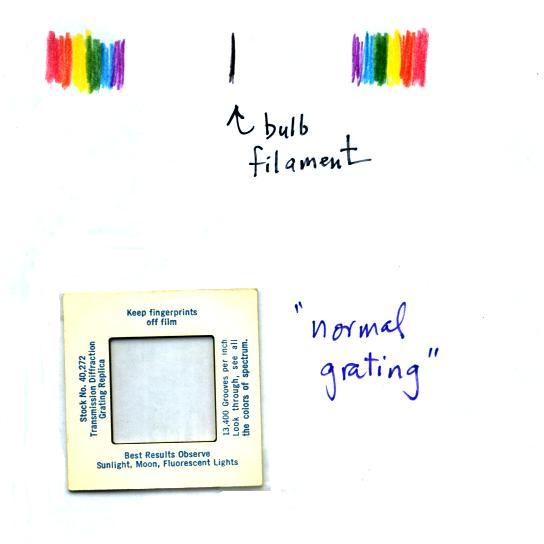

You were able to use one of the diffraction gratings handed

out in class to separate the white light produced by the bulb

into its separate colors.

When you looked at the bright white bulb filament through one

of the diffraction gratings the colors were smeared out to the

right and left as shown at left below.

You may need to rotate the slide 90 degrees to see the spectrum

as shown above.

Here are the answers to the two electric field questions

embedded earlier in the notes.

#1. The ground can be either negatively or positively

charged. If the ground were negatively charged the positive

charge would be attracted to the ground and the

negative charge repelled and pushed upward. That's not

what is happening. So the ground must be positively charged.

The positive charge is creating the force that causes the

positive charge to move upward. So that too must be

direction that the electric field arrow is pointing.

#2. To begin to answer the question we

imagine placing a + charge at Point X.

The center charge will be repelled by the charge on the left

and attracted to the charge on the right. The center charge

would move toward the right.

The electric field arrow shows the direction of the force on

the center charge. Since we've determined the

+ charge will move to the right,

that's the direction the electric field arrow

should point. The electric field arrow will point toward the

right.