Wednesday Jan. 13, 2016

A couple of songs from Lissie:

"Record

Collector" (4:14) (recorded in the studios of KCMP FM,

Minnesota Public Radio), and "In Sleep"

(5:23) part of a set at the end of the Guitar

Center's Singer/Songwriter 2 Competition Finals at Hotel

Café in Hollywood (Mar., 2013) to check out the audio

system in ILC 150.

Several more songs from the same artist are included below.

"They All

Want You" (4:14), and "Further

Away" (4:14) from the Bing Lounge at 101.9 KINK FM

(Portland, OR).

"Love

in the City" (3:46), "The Habit"

Live at Hotel San Jose, SXSW 2013 (4:26)

Today's lecture notes are shown below.

Information about this class and course requirements

ATMO 170 is off and running once again. We

first briefly discussed the Course

Information handout. Please read through that information

carefully on your own and let me know if you have any

questions or concerns.

A textbook is not required for this class. If you want a

different and more complete picture of the subject, you might want

to purchase one of the textbooks that are being used in the other

ATMO 170A1 sections. Or if you'd like to borrow one of the instructor copies of introductory

level textbooks that I have in my office, just let me

know. Otherwise you should be able to do perfectly well in

the class by reading the online notes. And you should read

the online notes even if you are in class.

A set of photocopied ClassNotes (available in the ASUA

Bookstore in the Student Union) is "required." You should

try to purchase a copy as soon as you can because we may well be

using them in class on Friday. If you know someone with

notes leftover from the Fall or Spring 2015 semesters they will

work fine.

Writing is an important part of

this class and is described in more detail on the Writing Requirements handout.

Please have a careful look

at that also and

let me know if you have any questions.

The first half of your writing grade is an experiment

report. You only need to do one of the experiments, so think

about which of the experiments (listed on the handout) you might

like to do. I'll bring a signup sheet to class on

Friday. I'm also planning on bringing about 40 sets of

Experiment #1 materials to class on Friday for checkout.

Checkout is first come first served. Materials for the other

experiments will be handed out at roughly 3-week intervals.

The so-called One Side of One Page (1S1P) reports make up the

second part of your writing grade. Topics will appear

periodically during the semester on the class webpage. As

you write reports you will earn points (the exact number of points

will depend on the topic and the quality of your report).

Your goal should be to earn 45 1S1P pts, the maximum number

allowed, by the end of the semester.

You'll be allowed to revise and raise your grade on the first

draft of your experiment report. So you should be able to

earn a pretty high score on that. And, unless you

procrastinate, you can just keep on writing 1S1P reports until

you've earned 45 points. There's no reason not to earn a

high writing grade. The writing grade gets averaged in with

your quiz scores and, as the example below shows, can have a

significant and beneficial effect on your overall grade.

Grade example

Your final grade in this class will depend on your quiz scores,

how much extra credit you earn (from optional take home and in

class assignments), your writing grade, and (perhaps) your score

on the final exam. A sample grade report from one of the

Fall 2015 sections of this class is shown below (most of the

numbers are class averages).

Doe_J

quiz1 -42 (170 pts possible) 75.3% quiz scores

quiz2 -51 (175 pts possible) 72.9%

quiz3 -47 (175 pts possible) 73.1%

quiz4 -52 (175 pts possible) 70.3%

2.5 EC points (3.3 pts possible) extra credit earned on optional assignments

writing scores

writing scores: 32.0 (expt/book report) + 45.0 (1S1P pts)

writing grade: 96.3%

overall averages (prior to the Final

Exam)

average (no quiz scores dropped): 77.6% + 2.5 =

80.0%

average (lowest quiz score dropped): 79.4% + 2.5 = 81.9%

Final exam score: 76.0%

Overall grade:

80.7% (B)

The 4 quiz grades are shown at the top.

Students that did turn in the Optional Assignments

earned on average 2.5 pts of extra credit during the

semester. You will have the opportunity to earn at least 3

extra credit points.

A score of 32 points (out of 40) on the experiment report and 45

1S1P points resulted in a writing percentage grade of 96.3%.

There's no good reason not to end up with a writing score close to

100% (or even greater than 100%)

The overall average without any quiz scores dropped is shown

next. Since the result, 80.0%, is less than 90.0% the

average student last fall did have to take the final exam

The second average (with the lowest score dropped) is a little

higher, 81.9%.

If you do well on the final exam it will count 40% of

your overall grade (trying to maximize the benefit it can

have). If you don't do so well on the final it only counts

20% (minimizing the damage it can cause). In this example

the final exam score (76%) was lower than the 81.9% value, so the

final exam only counted 20% and the overall score was 80.7%.

Be sure to note that even with C grades on each of the quizzes and

a C on the Final Exam you could well end up with a B in the

class. That is possible when you have a high writing grade

and also have some extra credit points.

"Chapter 1" - the earth's atmosphere

We did cover a little course material on this

first day of class so that you can get an idea of how that will

work. Also I won't feel so bad about not covering new

material on the last day of class in May.

If we were using a book

we'd start in Chapter 1 and here's some of what we would first

be looking at in this course.

We will come back to the first item, the

composition of the atmosphere, today.

Before we do that however, here

are a few questions to get you thinking about the air around

you. We didn't really cover any

of this in class.

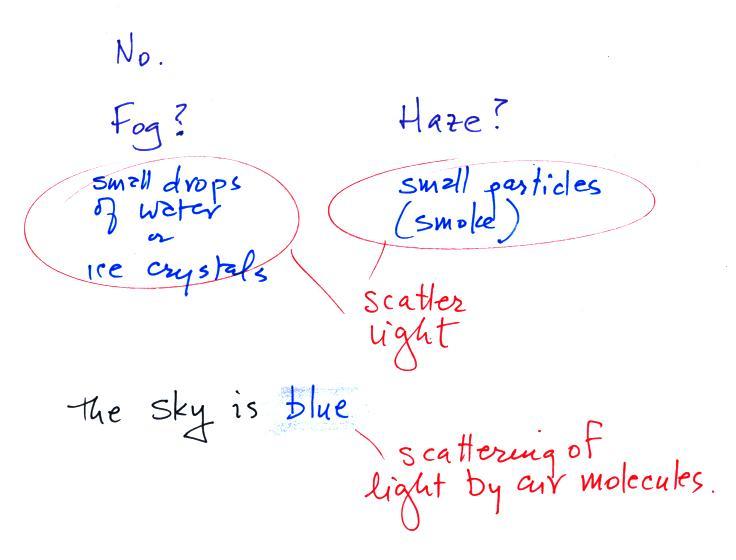

Can we see air?

Air is mostly clear, transparent, and invisible. Most

gases are invisible. Sometimes the air looks foggy,

hazy, or smoggy. In those cases you are probably

"seeing" small water droplets or ice crystals (fog) or small

particles of dust or smoke (haze and smog). The

particles themselves may be too small to be seen with the

naked eye but are visible because they scatter (redirect)

light. I didn't really mention or explain what

that is but it's a pretty important concept and we

will learn more about it soon.

And to be completely honest air isn't really invisible.

If you shine a bright light through enough air, such as when

sunlight shines through the atmosphere, the air (the sky)

appears blue. This is a little more complicated form of

scattering of sunlight by air molecules. We'll come back

to this later as well.

Can you

smell air?

I don't think you can smell or taste air (air containing

nitrogen, oxygen, water vapor, argon and carbon

dioxide). But there are also lots of other odors you can

sometimes smell (freshly cut grass, hamburgers on a grill,

etc). I don't consider these normal constituents of

the atmosphere.

You can probably also smell certain pollutants. I

suspect our sense of smell is sensitive enough for us to

detect certain air pollutants even when their concentration

is very small (probably a good thing because many of them

are poisonous).

Natural gas (methane) used in hot water

heaters, some stoves, and furnaces is odorless. A

chemical (mercaptan) is added to natural gas so that you can

smell it and know when there is a leak before it builds up

to a concentration that could cause an explosion.

It is harder to answer this question.

We're always in contact with air. Maybe we've grown so

accustomed to it we aren't aware of how it feels. We can

certainly feel whether the air is hot or cold, but that have

more to do with energy exchange between us and our

surroundings. And we can feel wind.

In a couple of weeks we will see that, here in the classroom,

air pressure is pressing on every square inch of our bodies with

12 or 13 pounds of force. If that were to change suddenly

I'm pretty sure we'd feel it and it would probably really hurt.

2 objectives for today:

1. You should be able to list the 5 most abundant gases in air

and say something (maybe more than one thing) about

each of them

2. You should be able to define or explain

dew point temperature

and you should know the meaning of the term monsoon.

Let's start with the most abundant gas in the atmosphere. I

poured some of that material (in liquid form) into a Styrofoam

cup. Here's a photo I took back in my office.

You can see the liquid, it's

clear, it looks like water. Probably a lot of you

knew this was nitrogen. Liquid nitrogen is very cold

and begins to boil (evaporate) at -321o

F.

The most abundant gas in the earth's atmosphere is

nitrogen. We'll use liquid nitrogen in several class

demonstration this semester mostly because it is so

cold.

Nitrogen was discovered in 1772 by Daniel Rutherford (a

Scottish botanist). Atmospheric nitrogen is relatively

unreactive and is sometimes used to replace air in packaged

foods to preserve freshness. You don't need to worry

about details like this for a quiz.

Oxygen is the second most abundant gas in the

atmosphere. Oxygen is the most abundant element (by

mass) in the earth's crust, in ocean water, and in the human

body. In liquid form it also becomes visible.

Some photographs of liquid oxygen (O2)

are shown above

(it

boils at -297o F).

It has a (very faint) pale blue color (I

was pretty disappointed when I first saw it because I had

heard it was blue and imagined it was a deeper more vivid

blue). When

heated (such as in an automobile engine) the oxygen

and nitrogen in air react to form compounds such as

nitric oxide (NO), nitrogen dioxide (NO2),

and nitrous oxide (N2O). Together as

a group these are called oxides of nitrogen; the first

two are air pollutants, the last is a greenhouse

gas. I'd

love to bring some liquid oxygen to class but

I'm not sure it's available on campus and you

probably need to be careful with it because it

is reactive.

I recently learned that liquid ozone (O3)

does have a nice deep blue color.

Liquid ozone (source

of this photograph).

It's probably very hard to find and is

also very (dangerously) reactive. Ozone gas is also

poisonous.

Here is a complete

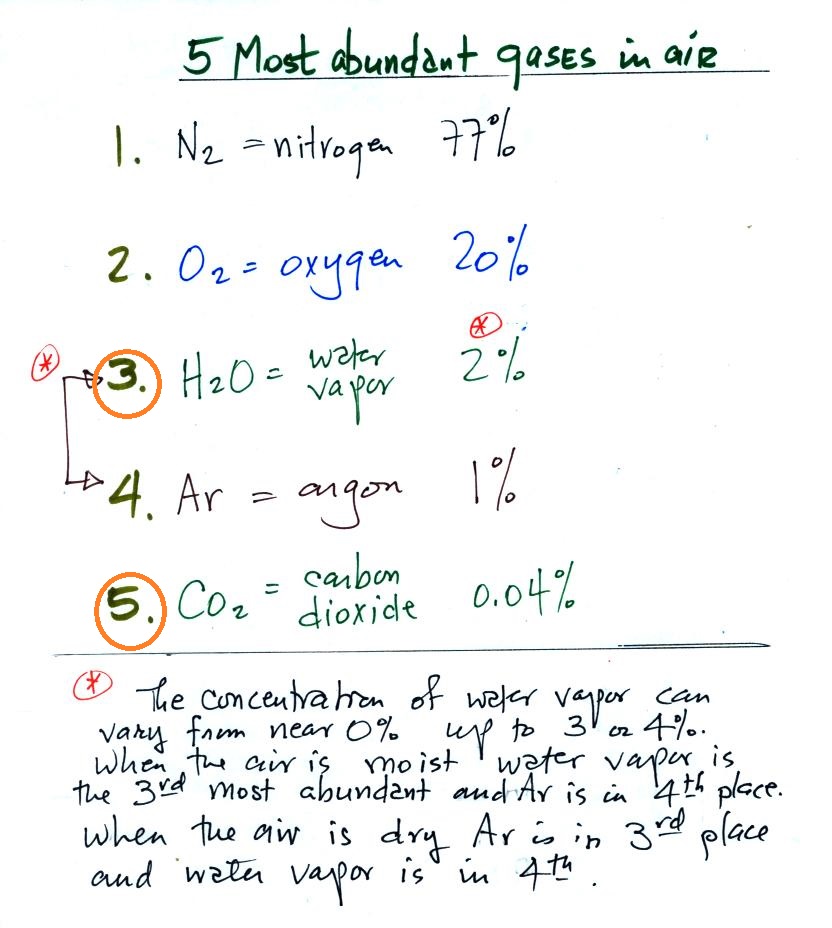

list of the 5 most abundant gases in air. And a note about the figures you'll find in these

online notes. They may differ somewhat from

those drawn in class. I often redraw them after class, or

use neater versions from a previous semester for improved clarity

(and so I can get the notes online more quickly).

With a little practice you should be able to start

with a blank sheet of paper and reproduce the list below.

Water vapor and argon are the 3rd and 4th most abundant

gases in the atmosphere. A 2% water vapor concentration is

listed above but it can vary from near 0% to as high as 3% or

4%. Water vapor is, in many locations, the 3rd most abundant

gas in air. In Tucson most of the year, the air is dry

enough that argon is in 3rd position and water vapor is 4th.

Water vapor and carbon dioxide are circled because they are

greenhouse gases.

Water vapor, a gas, is invisible. Water is the only

compound that exists naturally in solid, liquid, and gaseous

phases in the atmosphere.

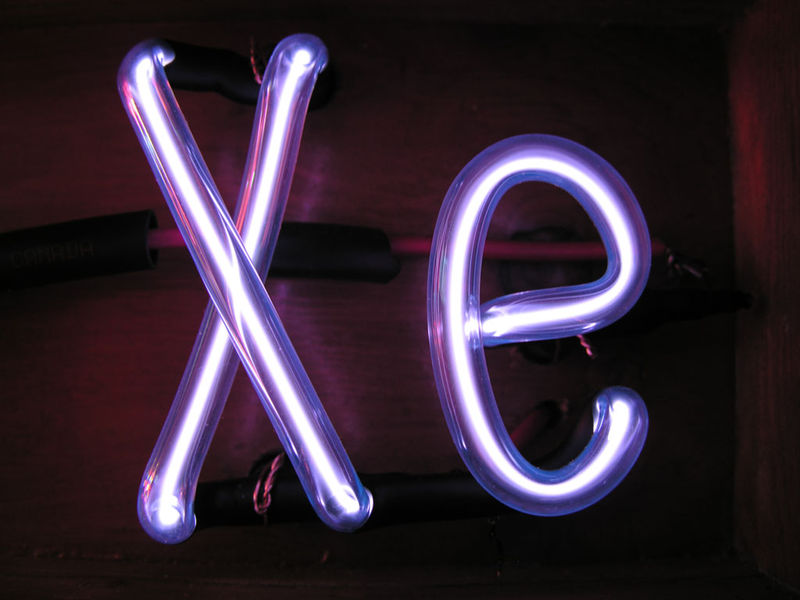

Argon is an unreactive noble gas (helium, neon, krypton, xenon, and radon are also inert gases).

Here's a

picture of solid argon ("argon ice"). It melts

at melts

at -309o F and

boils at -302o F;

it's doing both in this picture. (image source).

Here's a little more

explanation (from Wikipedia)

of why noble gases are so unreactive. You can gloss over

all these additional details if you want to, none of this was covered in class.

The noble gases have full valence electron shells. Valence electrons are the outermost electrons of an atom and are

normally the only electrons that participate in chemical bonding. Atoms

with full valence electron shells are extremely stable and

therefore do not tend to form chemical bonds and have little

tendency to gain or lose electrons (take electrons from or

give electrons to atoms of different materials).

Noble gases are often used used in "neon signs"; argon

produces a blue color. The colors produced by Argon (Ar),

Helium (He), Kryton (Kr), Neon (Ne) and Xenon (Xe), which are

also noble gases, are shown above (source

of the images). An electric current is

traveling through and heating the gas in the tube causing it to

emit light. You're seeing the light emitted by the gas

itself. The inert gases don't react with the metal

electrodes in the bulbs.

Fluorescent bulbs (including energy saving CFLs) often also

contain mercury vapor (which means you should properly dispose

of them when they burn out). The mercury vapor in CFL

bulbs emits ultraviolet light that strikes a phosphor coating on

the inside of the bulb. Different colors are emitted

depending on the particular type of phosphor used in the bulb.

This is solid carbon dioxide, better known as

dry ice. It doesn't melt, it sublimes. Sublimation

is a solid to gas phase change, evaporation is a liquid to gas

change. (

source of the

image above).

The concentration of carbon dioxide in air is much smaller

than the other gases (it's about 0.04% but you don't need to

remember the actual value). That doesn't mean it isn't

important. We'll spend a lot of time this semester talking

about water vapor and also carbon dioxide. Water vapor and

carbon dioxide are the two best known and most important

greenhouse gases. The greenhouse effect warms the

earth. Concentrations of greenhouse gases such as carbon

dioxide are increasing and there is concern this will strengthen

the greenhouse effect and cause global warming. That's a

topic we'll look at during the semester.

If we were using a textbook we'd probably find something like

the following table near the beginning of the book ( I found this

table a few years ago in a Wikipedia

article about the earth's atmosphere ).

I like our list of the 5 most abundant gases better. It's

much more manageable. There is almost too much information

in a chart like this, you might be overwhelmed and not remember

much. Also unless you are familiar with the units on the

numbers they might be confusing. And notice you don't find

water vapor in 3rd or 4th position near the top of the

chart. That's because this is a list of the gases in dry

air. Unless you're very attentive, you might miss that fact

and might not see water vapor way which is included at the bottom

of the chart.

If you click on the link above to the Wikipedia article on the

earth's atmosphere, you'll find that the list above has been

replaced with a shorter simpler list (much more like the one we

created in class).

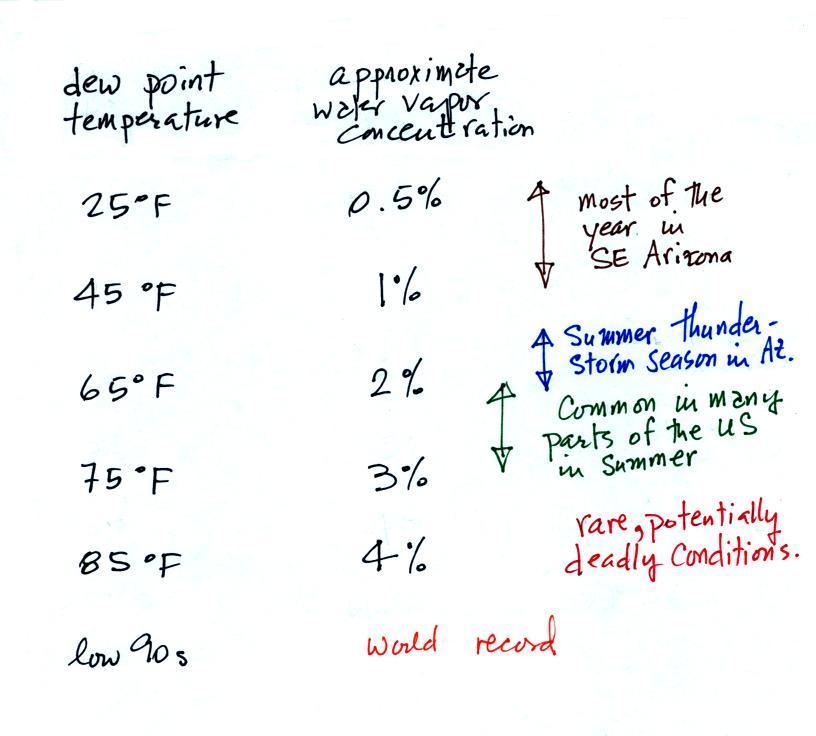

Dew point temperature and the

summer monsoon

Water plays many important roles in the

atmosphere. One of them is the formation of clouds, storms,

and precipitation. Meteorologists are very interested in

knowing and keeping track of how much water vapor is in the

air. One of the variables they use is the dew point

temperature. The value of the dew point gives you an idea of

how much water vapor is actually in the air. A high dew

point value means a higher the water vapor concentration.

The chart below gives a rough equivalence between

dew point temperature and percentage concentration of water

vapor in the air.

Note that for every 20 F increase in dew

point temperature, the amount of water vapor in the air

roughly doubles.

Air temperature will always be equal to or warmer than the

dew point temperature. Experiencing 80o F dew points would be

very unpleasant and possibly life threatening because your

body might not be able to cool itself ( the air

temperature would probably be in the 90s or maybe even

warmer). You could get

heatstroke and die.

Click here

to see current dew point temperatures across the U.S. Here's

a

link concerning unusually high, even record setting dew

point temperatures.

This is as far as we got

today in class. I've moved material on the summer

monsoon and the dew point's "2nd job" to the start of the

Fri., Jan. 15 classnotes.