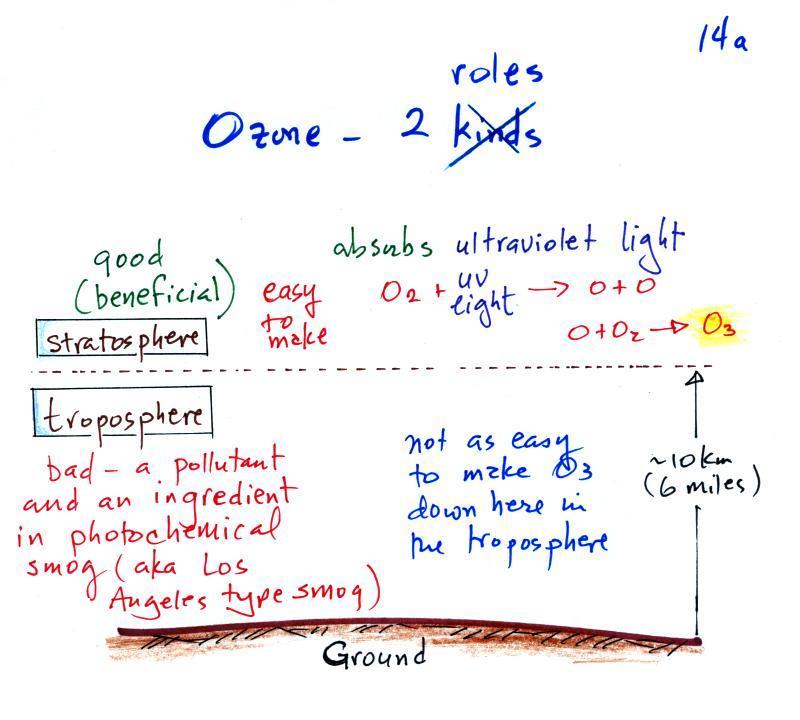

Good (stratospheric) and bad

(tropospheric) ozone

We'll first turn our attention to ozone.

Ozone has a kind of Dr.

Jekyll

and

Mr Hyde personality.

The figure above can be found on p.

14a in the photocopied ClassNotes. The ozone layer

(ozone in the stratosphere) is beneficial, it absorbs

dangerous high energy ultraviolet light (which would

otherwise reach the ground and cause skin cancer,

cataracts, and actually there are some forms of UV light

that would quite simply kill us).

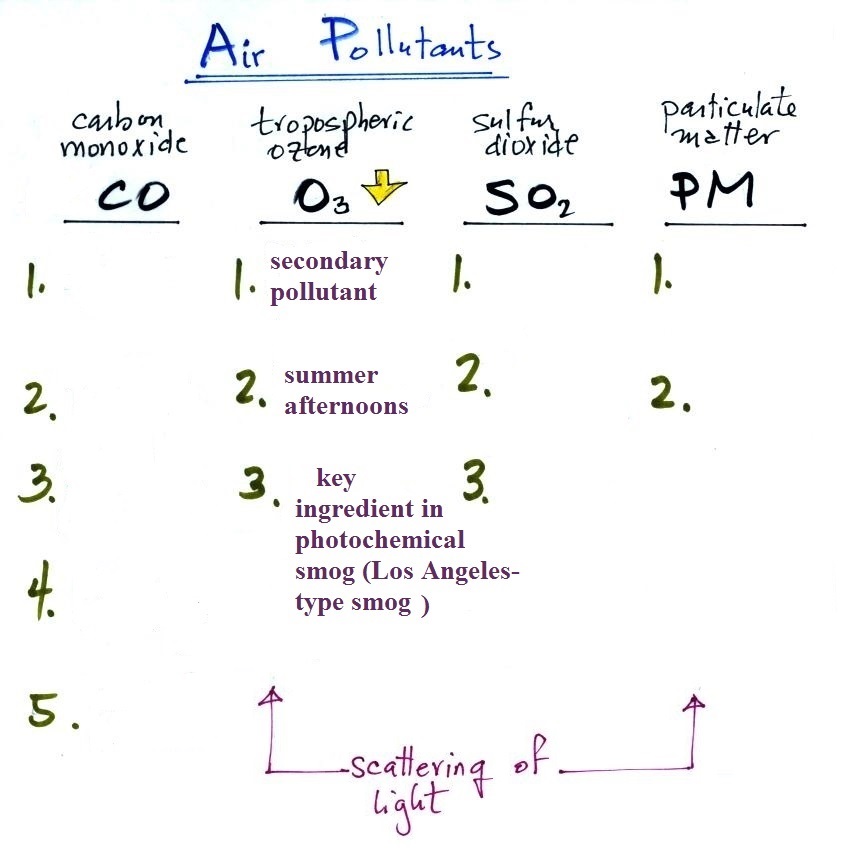

Ozone in the troposphere is bad, it is toxic and a pollutant. Tropospheric ozone is also a key component of photochemical smog (also known as Los Angeles-type smog)

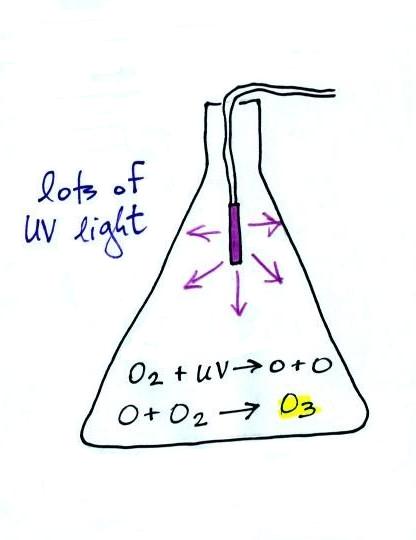

We'll be making some photochemical smog in a class demonstration. To do this we'll first need some ozone; we'll make use of the simple stratospheric recipe (shown above) for making what we need instead of the more complex tropospheric process (the 4-step process in the figure below). You'll find more details a little further down in the notes.

Ozone in the troposphere is bad, it is toxic and a pollutant. Tropospheric ozone is also a key component of photochemical smog (also known as Los Angeles-type smog)

We'll be making some photochemical smog in a class demonstration. To do this we'll first need some ozone; we'll make use of the simple stratospheric recipe (shown above) for making what we need instead of the more complex tropospheric process (the 4-step process in the figure below). You'll find more details a little further down in the notes.

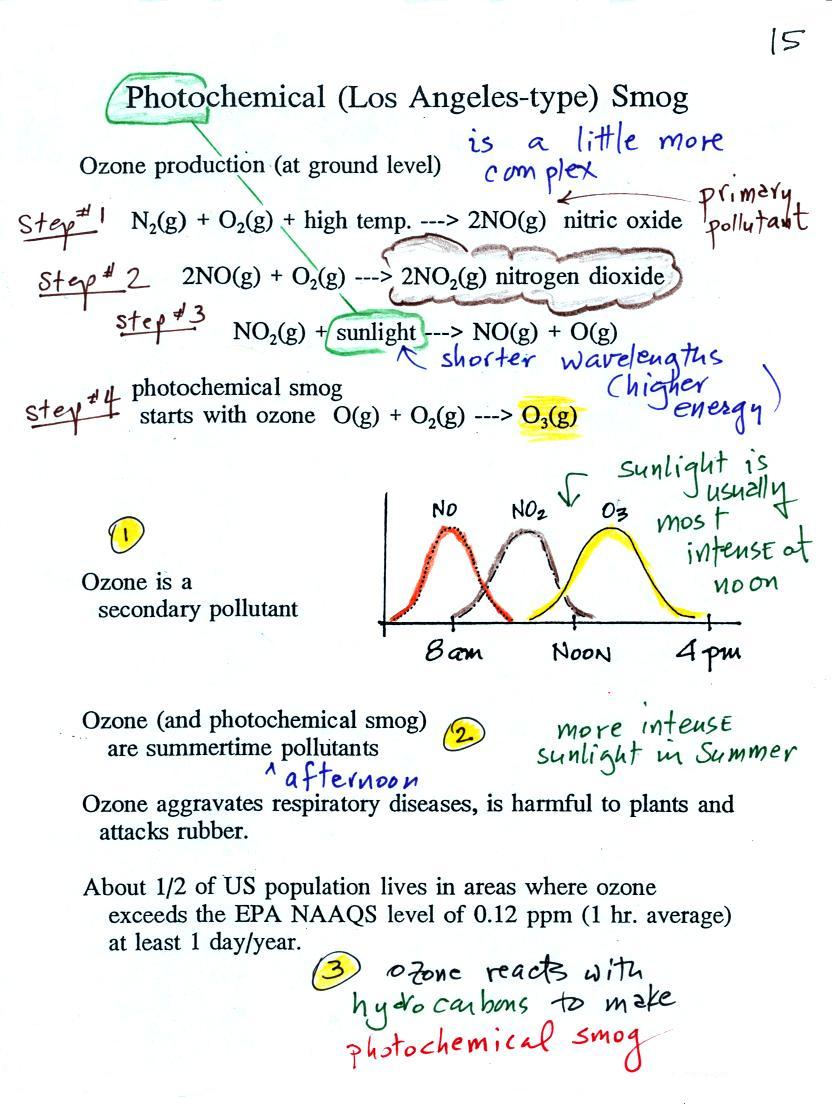

At the top of this figure

(p. 15 in the packet of ClassNotes) you see that a more

complex series of reactions is responsible for the

production of tropospheric ozone. The

production of tropospheric ozone begins with nitric oxide

(NO). NO is produced when nitrogen and oxygen in air

are heated (in an automobile engine for example) and

react.

The NO can then react with oxygen in the air to make nitrogen dioxide, the poisonous brown-colored gas that I used to make in class.

Sunlight can dissociate (split) the nitrogen dioxide molecule producing atomic oxygen (O) and NO. O and O2 react in a 4th step to make ozone (O3) just like happens in the stratosphere. Because ozone does not come directly from an automobile tailpipe or factory chimney, but only shows up after a series of reactions in the air, it is a secondary pollutant. Nitric oxide (NO) would be the primary pollutant in this example.

NO is produced early in the day (during the morning rush hour). The concentration of NO2 peaks somewhat later. Because sunlight is needed in step #3 and because sunlight is usually most intense at noon, the highest ozone concentrations are usually found in the afternoon. Ozone concentrations are also usually higher in the summer when the sunlight is more intense than at other times of year.

The NO can then react with oxygen in the air to make nitrogen dioxide, the poisonous brown-colored gas that I used to make in class.

Sunlight can dissociate (split) the nitrogen dioxide molecule producing atomic oxygen (O) and NO. O and O2 react in a 4th step to make ozone (O3) just like happens in the stratosphere. Because ozone does not come directly from an automobile tailpipe or factory chimney, but only shows up after a series of reactions in the air, it is a secondary pollutant. Nitric oxide (NO) would be the primary pollutant in this example.

NO is produced early in the day (during the morning rush hour). The concentration of NO2 peaks somewhat later. Because sunlight is needed in step #3 and because sunlight is usually most intense at noon, the highest ozone concentrations are usually found in the afternoon. Ozone concentrations are also usually higher in the summer when the sunlight is more intense than at other times of year.

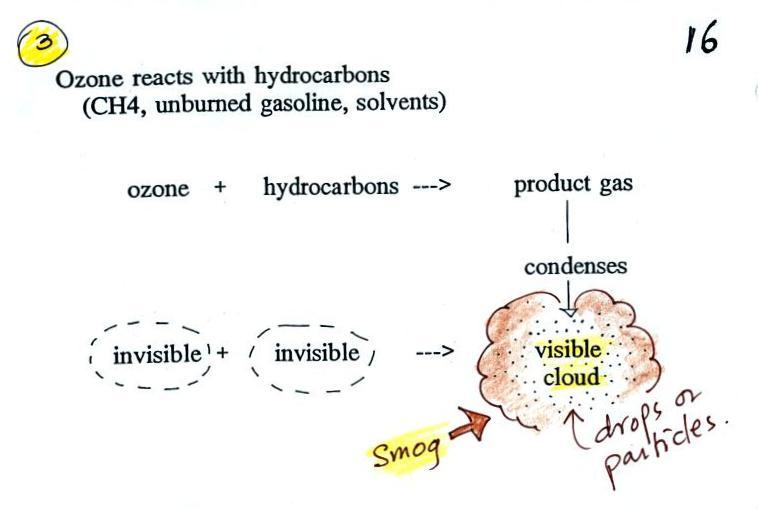

Once ozone is formed, the ozone can

react with a hydrocarbon of some kind to make a product

gas. The ozone, hydrocarbon, and product gas are all

invisible, but the product gas sometimes condenses to make

a visible smog cloud or haze. The cloud is composed

of very small droplets or solid particles. They're

too small to be seen but they are able to scatter light -

that's why you can see the cloud.

Here's a pictorial summary of the photochemical smog demonstration.

We started by putting a small "mercury vapor" lamp inside a flash. The bulb produces a lot of ultraviolet light (the bulb produced a dim bluish light that we could see, but the UV light is invisible so we had no way of really telling how bright it was). The UV light and oxygen in the air produced a lot of ozone (you could easily have smelled it if you had taken the cover off the flask).

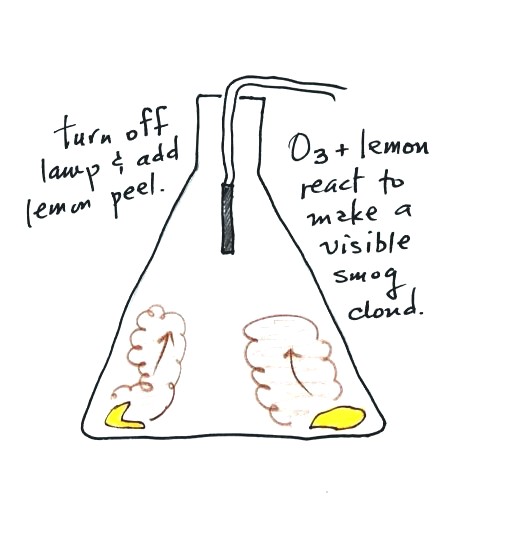

After a few minutes we turned off the lamp and put a few pieces of lemon peel into the flash. Part of the smell that comes from lemon peel is limonene, a hydrocarbon. The limonene gas reacted with the ozone to produce a product gas of some kind. The product gas condensed, producing a visible smog cloud (the cloud was white, not brown as shown above). We shined the laser beam through the smog cloud to reinforce the idea that we are seeing the cloud because the drops or particles scatter light.

Here's a video that I found of a slightly different version of the demonstration (you really don't miss much if you don't come to class). Instead of using UV light to produce the ozone the demonstration uses an electrical discharge (the discharge travels from the copper coil inside the flask to the aluminum foil wrapped around the outside of the flask). The overall effect is the same. The discharge splits an oxygen molecule O2 into two oxygen atoms.

O2 + spark ---> O + O

One of the oxygen atoms reacts with an oxygen molecule to form O3

O + O2

---> O3

The smog cloud produced in the video is a little thicker than the one produced in class. I suspect that is because they first filled the flask with pure oxygen, 100% oxygen, before making the ozone. I used air in the room which is 20% oxygen. More oxygen in the flask means more ozone and a thicker cloud of Los Angeles type smog.

Back to our summary list

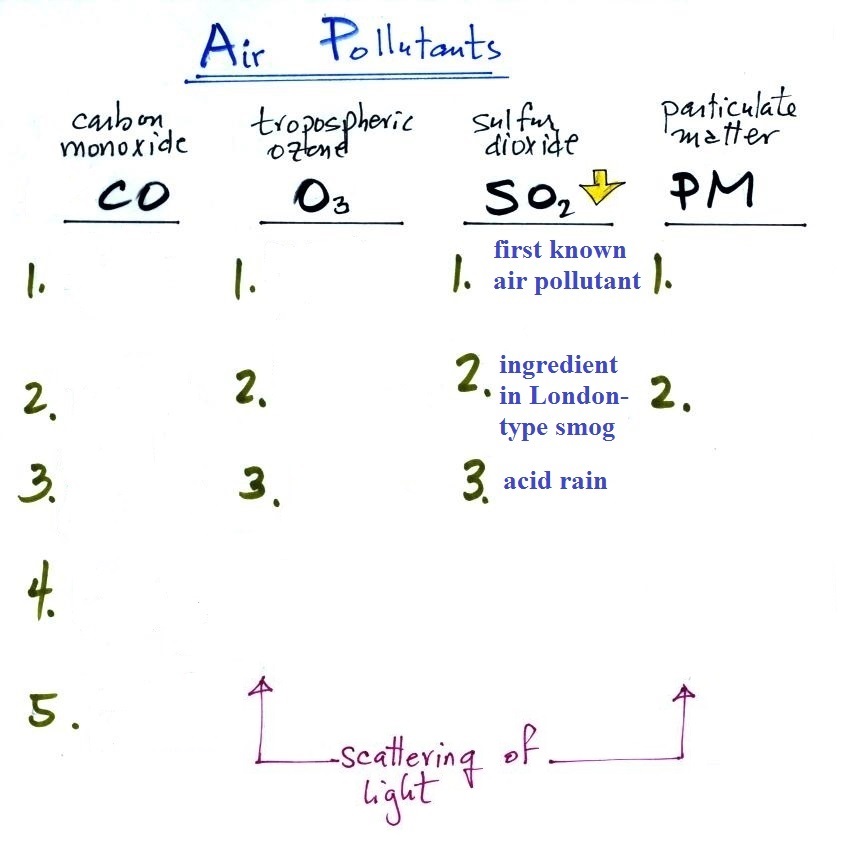

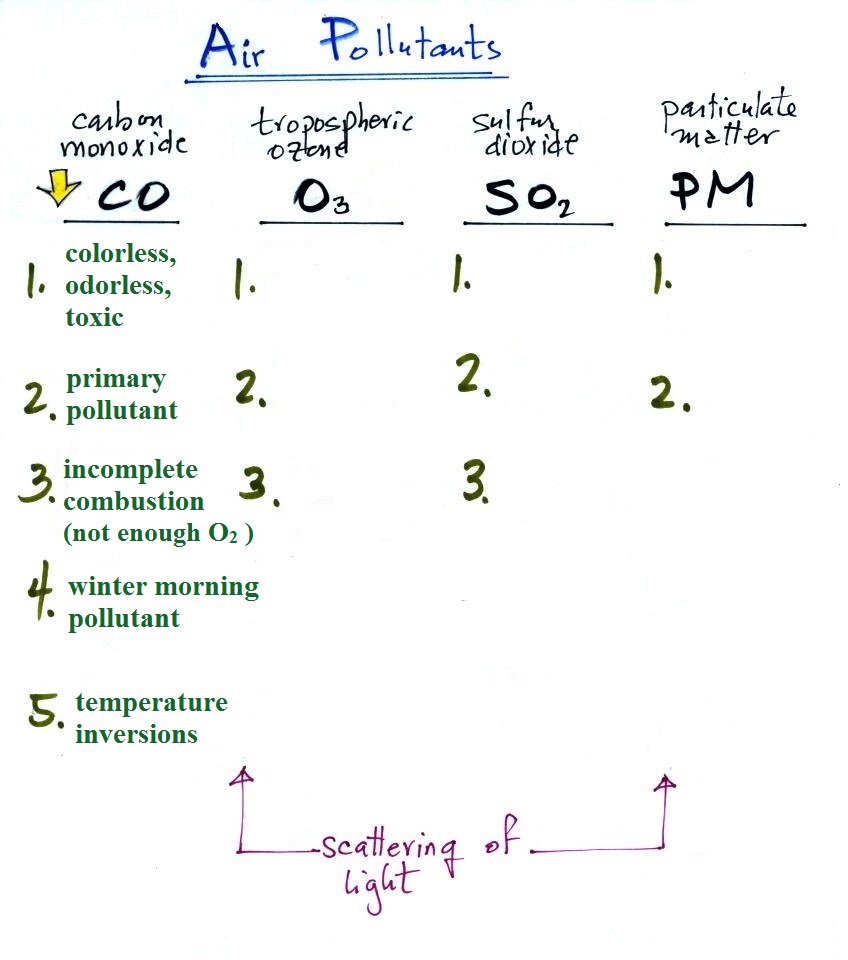

Sulfur dioxide (SO2 )

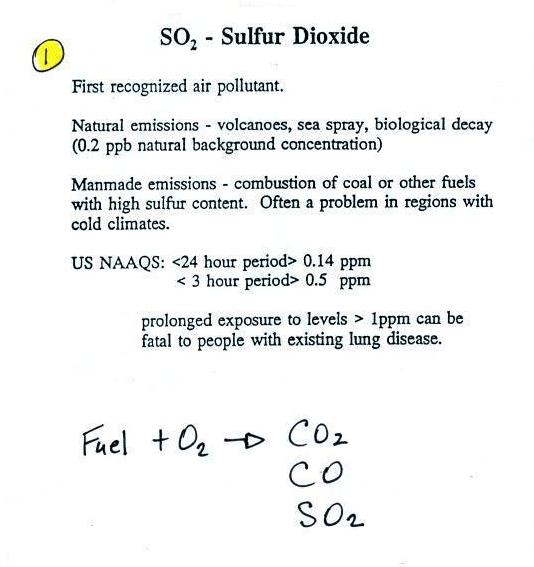

We turn now to the 3rd of the air pollutants we will cover, sulfur dioxide (SO2 ).

Sulfur dioxide is produced by the combustion of sulfur containing fuels such as coal. Combustion of fuel also produces carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide. People probably first became aware of sulfur dioxide because it has an unpleasant smell. Carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide are odorless. That is most likely why sulfur dioxide was the first pollutant people became aware of.

I've checked on the smell of sulfur dioxide class and have found two descriptions: one described it as the smell of rotten eggs (I associate that with hydrogen sulfide, H2S, which is also poisonous), the second is a pungent irritating odor which is what I remember. Apparently sulfur dioxide is one of the smells in a freshly struck match.

Volcanoes are a natural source of sulfur dioxide.

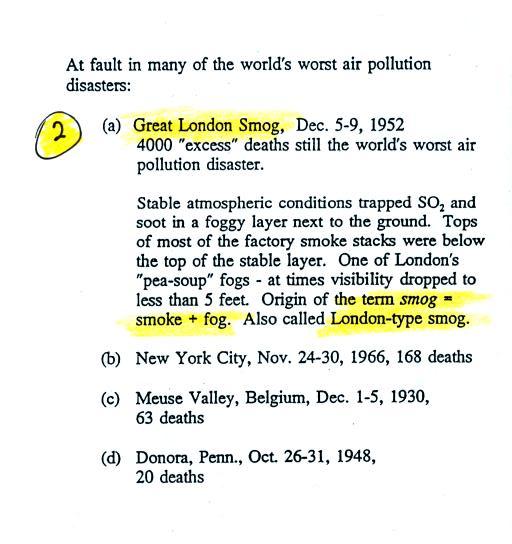

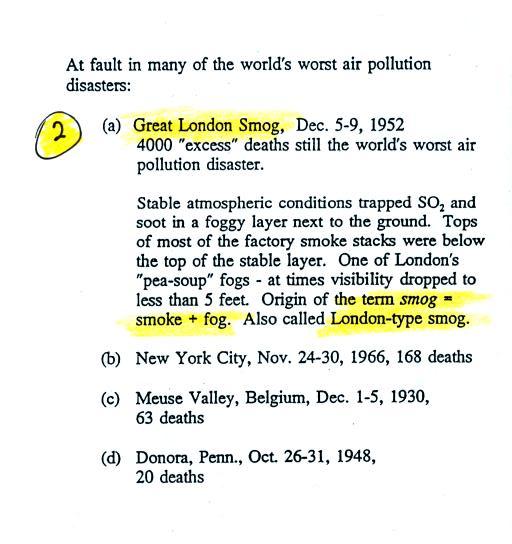

London-type smog

Sulfur dioxide has been involved in some of the world's worst air pollution disasters. Still the deadliest, as best I can tell, is the Great London Smog of 1952. At that time people burned coal in their homes and coal was burned in factories. In December 1952 the atmosphere was stable, SO2 and smoke from all the coal fires was emitted into air at ground level and couldn't mix with cleaner air above. The SO2 concentration was able to build to dangerous levels. 4000 people died during this 4 or 5 day period. As many as 8000 additional people died in the following weeks and months. Perhaps 100,000 people became ill.

The inversion layer in this case lasted for several days and was produced in a different way than the surface radiation inversions we heard about when covering carbon monoxide. Surface radiation inversions usually only last for a few hours.

The term smog, a contraction of smoke + fog, was invented to describe a mixture of smoke and fog, something that was fairly common in the winter in London. The 1952 event was an extreme case. Now we distinguish between "London-type smog" which contains sulfur dioxide and photochemical or "Los Angeles-type smog" which contains ozone.

Sulfur dioxide has been involved in some of the world's worst air pollution disasters. Still the deadliest, as best I can tell, is the Great London Smog of 1952. At that time people burned coal in their homes and coal was burned in factories. In December 1952 the atmosphere was stable, SO2 and smoke from all the coal fires was emitted into air at ground level and couldn't mix with cleaner air above. The SO2 concentration was able to build to dangerous levels. 4000 people died during this 4 or 5 day period. As many as 8000 additional people died in the following weeks and months. Perhaps 100,000 people became ill.

The inversion layer in this case lasted for several days and was produced in a different way than the surface radiation inversions we heard about when covering carbon monoxide. Surface radiation inversions usually only last for a few hours.

The term smog, a contraction of smoke + fog, was invented to describe a mixture of smoke and fog, something that was fairly common in the winter in London. The 1952 event was an extreme case. Now we distinguish between "London-type smog" which contains sulfur dioxide and photochemical or "Los Angeles-type smog" which contains ozone.

Most of the

photographs below come

from articles published in 2002 and 2012, the

50th and 60th anniversaries of the event.

Here are some interesting photographs of early and mid 20th century London.

The sulfur dioxide didn't kill people directly. Rather it would aggravate an existing condition of some kind. The SO2 probably also made people susceptible to bacterial infections such as pneumonia. Here's a link that discusses the event and its health effects in more detail.

The Clean Air Act of 1956 in England reduced smoke pollution and emissions of sulfur dioxide. However an article in The Telegraph notes that London air now exceeds recommended concentration limits for nitrogen dioxide and particulates.

Air pollution disasters involving sulfur dioxide have also occurred in the US. One of the deadliest events was in 1948 in Donora, Pennsylvania.

The reference material that contained this photographed clearly stated "This eerie photograph was taken at noon on Oct. 29, 1948 in Donora, PA as deadly smog enveloped the town. 20 people were asphyxiated and more than 7,000 became seriously ill during this horrible event."

The photograph below shows some of the mills that were operating in Donora at the time. Not only where the factories adding pollutants to the air they were undoubtedly adding hazardous chemicals to the water in the nearby river.

from: http://www.eoearth.org/article/Donora, Pennsylvania

The US passed its own Clean Air Act in 1963. There have been several major revisions since then. The EPA began in late 1970 (following an executive order signed by President Nixon)

"When Smoke Ran Like Water," a book about air pollution is among the books that you can check out, read, and report on to fulfill part of the writing requirements in this class (though I would encourage you to do an experiment instead). The author, Devra Davis, lived in Donora Pennsylvania at the time of the 1948 air pollution episode.

The caption to this

photo from The Guardian reads

"Arsenal goalkeeper Jack Kelsey peers into the fog. The 'smog' was so thick the game was eventually stopped." |

The smog in this photo is the thickest I was able to find. Visibility here is perhaps 10 or 20 feet. (source of this image) |

Buses had to creep along to

avoid hitting someone or something.

from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/health/2545747.stm |

Someone would often walk

out ahead of a bus to be sure the way was clear.

from: http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/england/2543875.stm |

You can get a feel for the

cause of the smog

in this photograph by Paul Lowry in an article in SAGEMagazine. |

|

Here are some interesting photographs of early and mid 20th century London.

The sulfur dioxide didn't kill people directly. Rather it would aggravate an existing condition of some kind. The SO2 probably also made people susceptible to bacterial infections such as pneumonia. Here's a link that discusses the event and its health effects in more detail.

The Clean Air Act of 1956 in England reduced smoke pollution and emissions of sulfur dioxide. However an article in The Telegraph notes that London air now exceeds recommended concentration limits for nitrogen dioxide and particulates.

Air pollution disasters involving sulfur dioxide have also occurred in the US. One of the deadliest events was in 1948 in Donora, Pennsylvania.

The reference material that contained this photographed clearly stated "This eerie photograph was taken at noon on Oct. 29, 1948 in Donora, PA as deadly smog enveloped the town. 20 people were asphyxiated and more than 7,000 became seriously ill during this horrible event."

The photograph below shows some of the mills that were operating in Donora at the time. Not only where the factories adding pollutants to the air they were undoubtedly adding hazardous chemicals to the water in the nearby river.

from: http://www.eoearth.org/article/Donora, Pennsylvania

The US passed its own Clean Air Act in 1963. There have been several major revisions since then. The EPA began in late 1970 (following an executive order signed by President Nixon)

"When Smoke Ran Like Water," a book about air pollution is among the books that you can check out, read, and report on to fulfill part of the writing requirements in this class (though I would encourage you to do an experiment instead). The author, Devra Davis, lived in Donora Pennsylvania at the time of the 1948 air pollution episode.