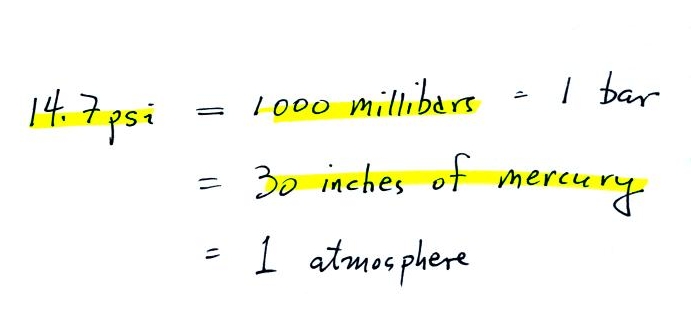

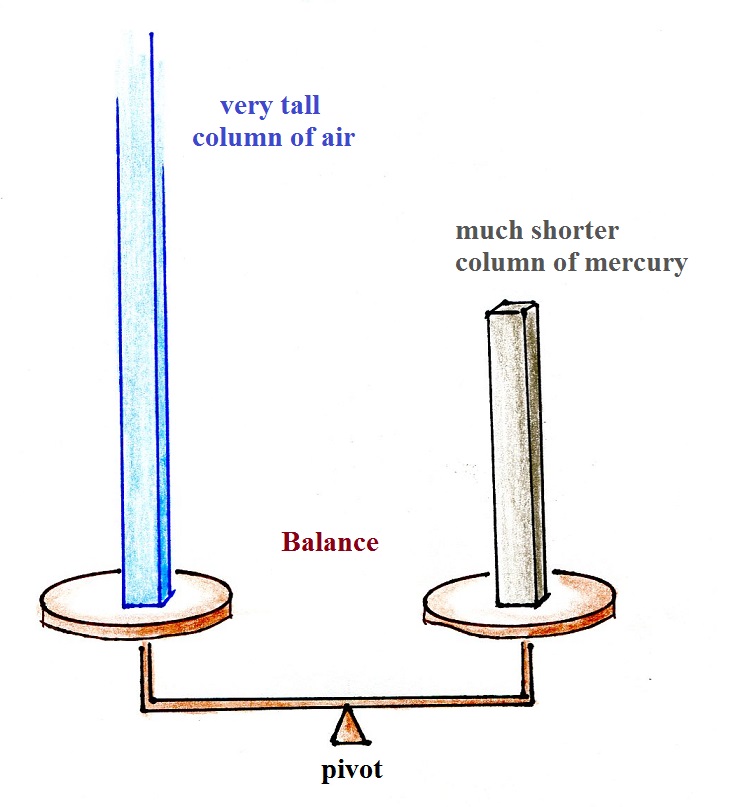

You can't use an

ordinary pan balance to weight the atmosphere. A

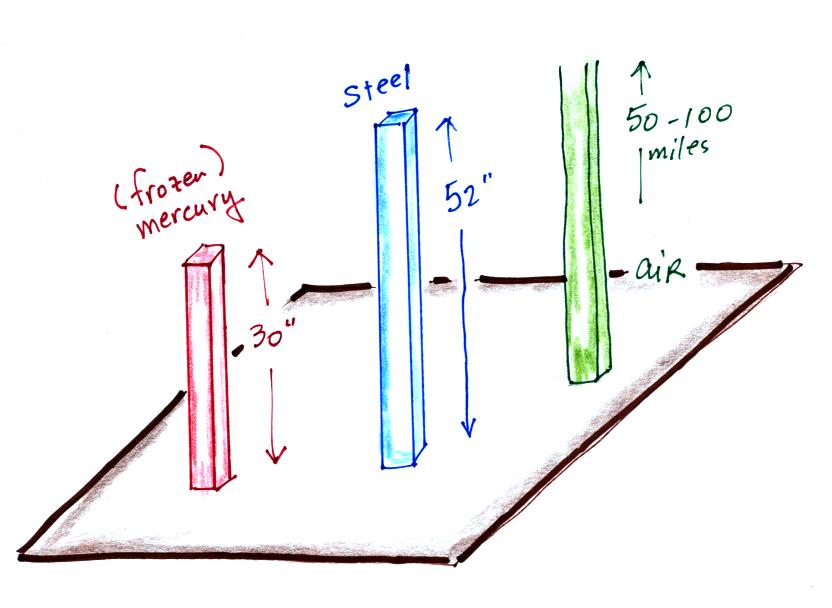

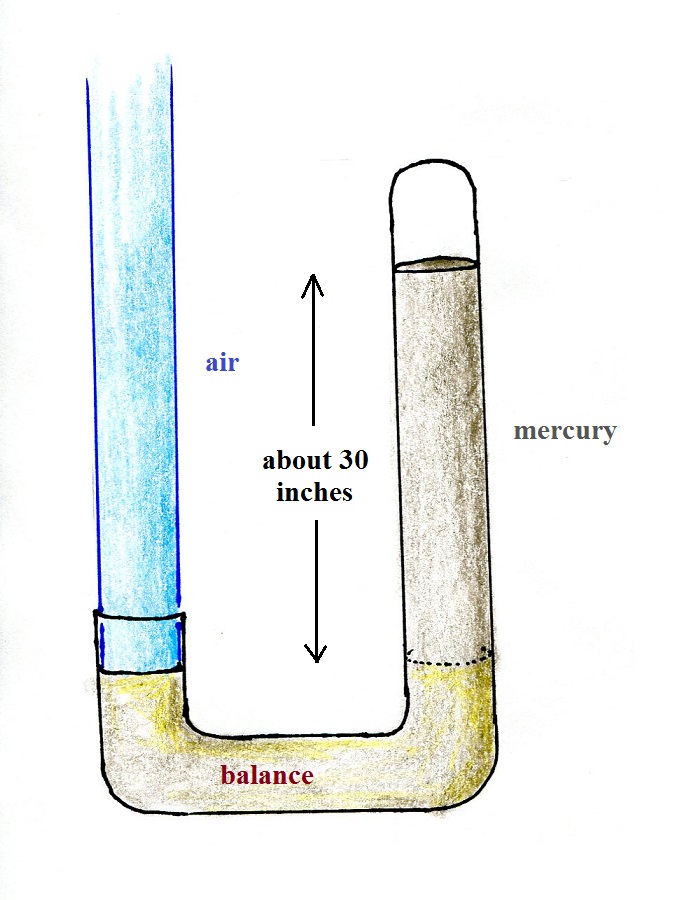

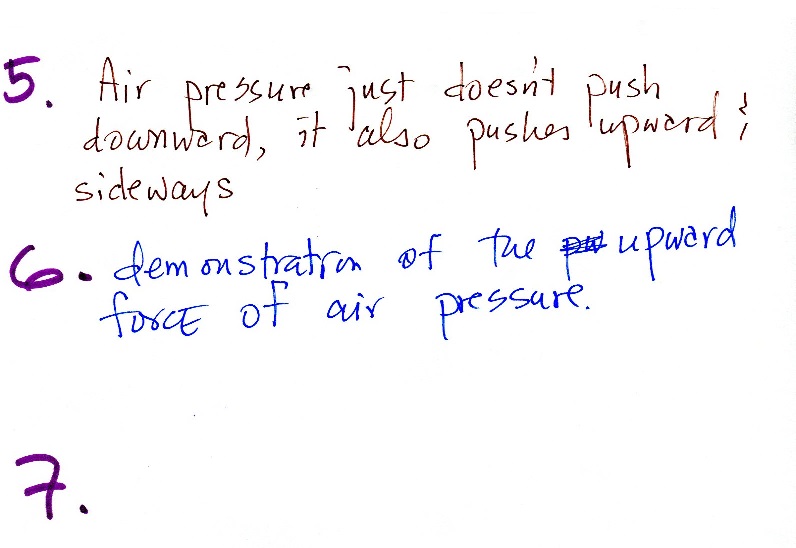

U-shaped tube filled with some kind of liquid that can

slosh back and forth would work. Such an instrument

is called a manometer and is often filled with mercury.

|

|

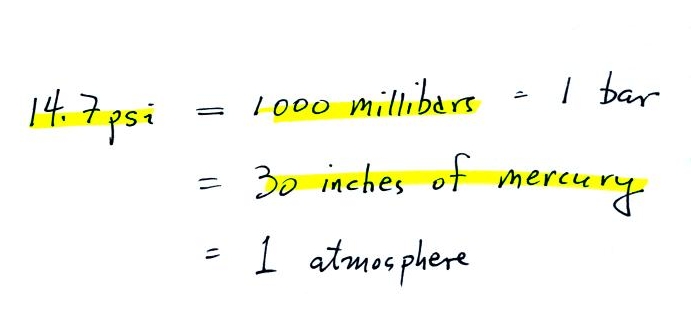

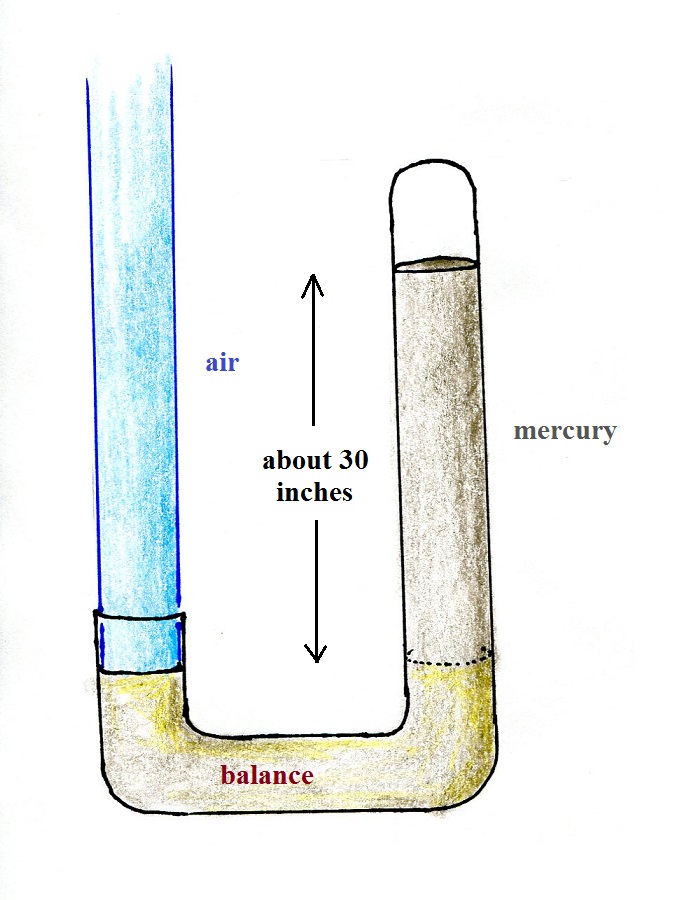

To turn the manometer

into a true barometer, we'll extend the tube on the right

and close the top so that air isn't pushing down on the

mercury. We'll also use somewhat larger cylindrical

columns of air and mercury that completely fill the

insides of the tube.

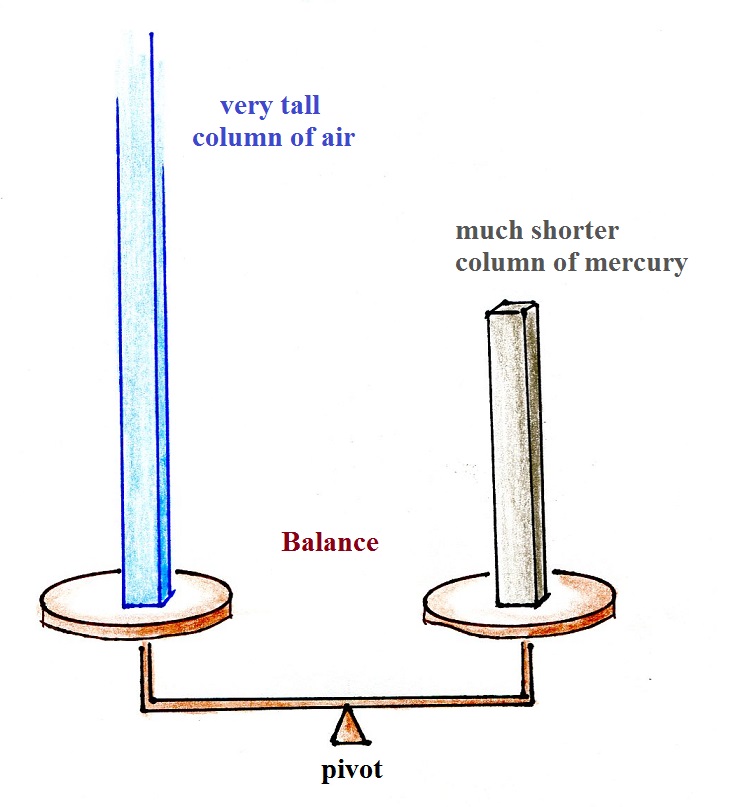

The weight of a very tall cylindrical column of air is

balanced by a much shorter cylindrical column of

mercury. The height of the mercury column will change

as air pressure varies.

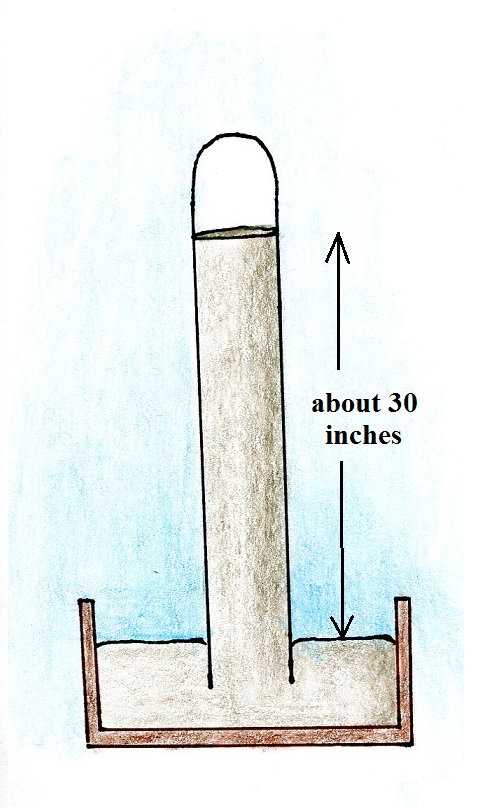

Mercury is a liquid. You need a liquid that can slosh

back and forth in response to changes in air pressure.

Mercury is also very dense which means the barometer won't

need to be as tall as if you used something like

water. A water barometer would need to be over 30 feet

tall. With mercury you will need only a 30 inch tall

column to balance the weight of the atmosphere at sea level

under normal conditions (remember the 30 inches of mercury

pressure units mentioned earlier). Mercury also has a

low rate of evaporation so you don't have much mercury gas

at the top of the right tube (there's some gas, it doesn't

produce much pressure, but it would be hazardous you if you

were to start to breath it).

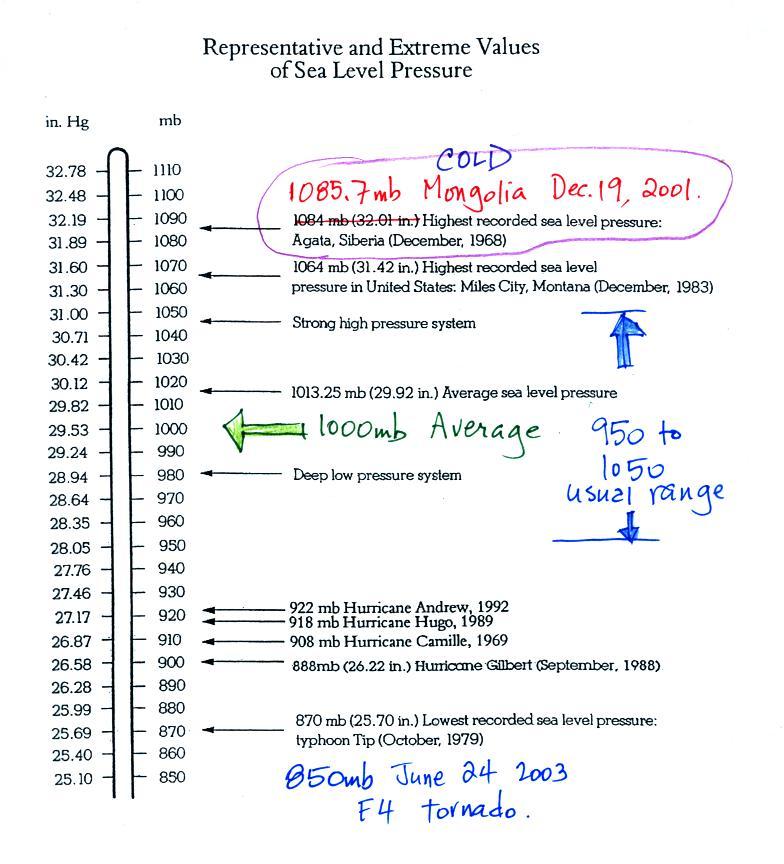

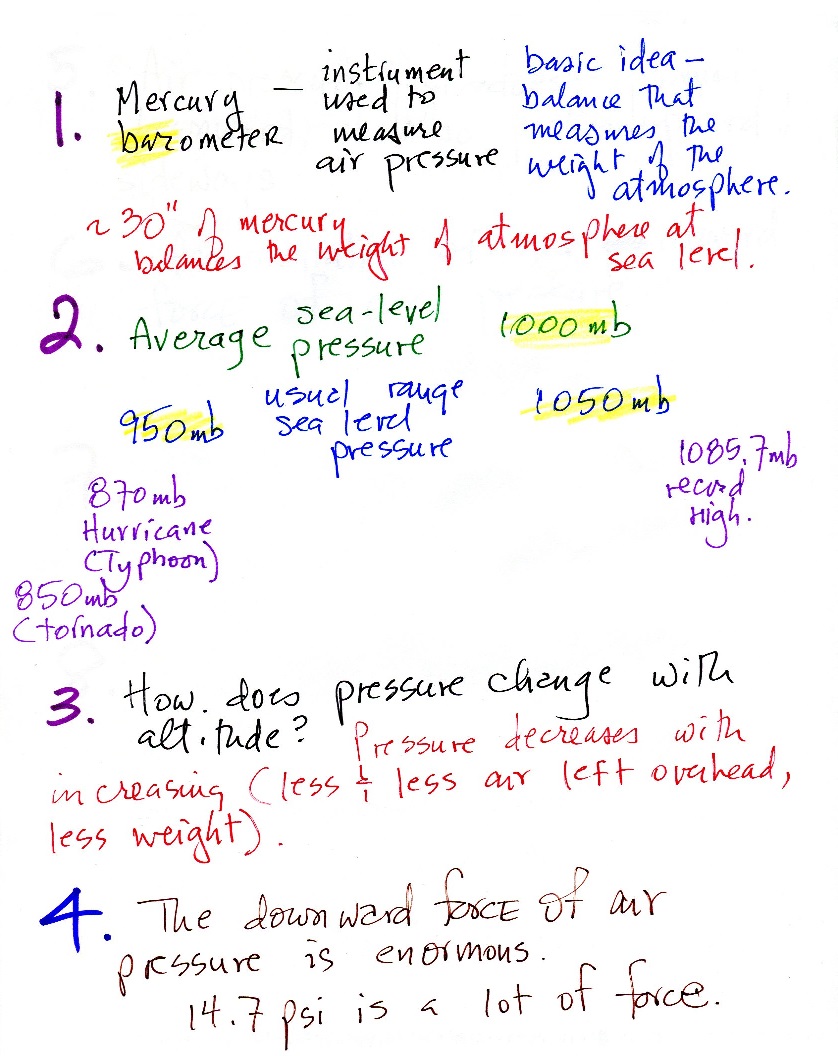

2. Average and extreme sea level pressure values

Average sea level atmospheric pressure is about 1000 mb.

The figure above (p. 30 in the photocopied Class Notes) gives

1013.25 mb but 1000 mb is close enough in this class.

The actual pressure can be higher or lower than this average

value and usually falls between 950 mb and 1050

mb.

The figure also includes record high and low pressure

values. Record high sea level pressure

values occur during cold weather. The TV

weather forecast will often associate hot weather with high

pressure. They are generally referring to upper level

high pressure (high pressure at some level above the ground)

rather than surface pressure. You'll

sometimes here this upper level high pressure referred to as a

ridge, we'll learn more about this later in the semester.

Note that record high surface pressure values are observed

in the winter when it is cold.

There is some question about the accuracy of the 1085.7 mb

value above. The problem is that the pressure was

measured at over 5000 feet altitude and a calculation was

needed to figure out what the pressure would have been if the

location were at sea level. That calculation can

introduce uncertainty. But you don't really need to be

concerned with all that, I just wanted to give you an idea of

how high sea level pressure can get.

Most of the record low pressure values have all been set by

intense hurricanes.

Hurricane Wilma in 2005 set a new record low sea level

pressure reading for the Atlantic, 882 mb. Hurricane

Katrina had a pressure of 902 mb. The following table

lists some of the information on hurricane strength from p.

146a in the photocopied ClassNotes. 2005 was a very

unusual year, 3 of the 10 strongest N. Atlantic hurricanes

ever occurred in 2005.

You may remember Hurricane Patricia off the west coast of

Mexico last fall. Patricia set a new surface low

pressure record for the Western Hemisphere - 879 mb.

Sustained winds of 200 MPH were observed.

Most

Intense North Atlantic Hurricanes

|

Most

Intense Hurricanes

to hit the US Mainland

|

Wilma

(2005) 882 mb

Gilbert (1988) 888 mb

1935 Labor Day 892 mb

Rita (2005) 895 mb

Allen (1980) 899

Katrina (2005) 902

|

1935

Labor Day 892 mb

Camille (1969) 909 mb

Katrina (2005) 920 mb

Andrew (1992) 922 mb

1886 Indianola (Tx) 925 mb |

What makes hurricanes so intense is the pressure gradient,

i.e. how quickly pressure changes with distance (horizontal

distance). Pressure can drop from near average values

(1000 mb) at the edges of the storm to the low values shown

above at the center of the storm. This large pressure

gradient is what causes the strong winds found in a hurricane.

The 850 mb pressure value measured in 2003 inside a strong

tornado in Manchester, South Dakota (F4 refers to the Fujita

scale rating, F5 is the highest level on the scale).

This is very difficult (and very dangerous) thing to try to

do. Not only must the instruments be built to survive a

tornado but they must also be placed on the ground ahead of an

approaching tornado and the tornado must then pass over the

instruments (also the person placing the instrument needs to

get out of the way of the approaching tornado).

You can experience much lower pressure values than shown above

(roughly 700 mb) by just driving up to Mt. Lemmon. Very

strong vertical changes in pressure are usually almost

balanced exactly by gravity.

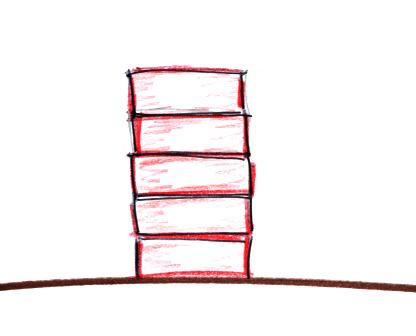

3. Changes in atmospheric pressure with altitude

If you remember and understand the statement

atmospheric

pressure at any level in the atmosphere

depends on (is determined by)

the

weight of the air overhead

You can quickly and easily figure out what happens to air

pressure as you move upward in the atmosphere. A

pile of bricks can also help; here's

a picture of 5 bricks stacked on top of each

other.

Each of the bricks weighs 5 pounds, there's a

total of 25 pounds of weight. At

the bottom of the pile you would measure a weight of

25 pounds. If you moved up a brick you would

measure a weight of 20 pounds, the weight of the four

bricks that are still above. The pressure would

be less. Weight and pressure will decrease as

you move up the pile.

Layers

of air in the atmosphere is not too

much different from a pile of

bricks. Pressure at any level is

determined by the weight of the air

still overhead. Pressure

decreases with increasing altitude

because there is less and less air

remaining overhead.

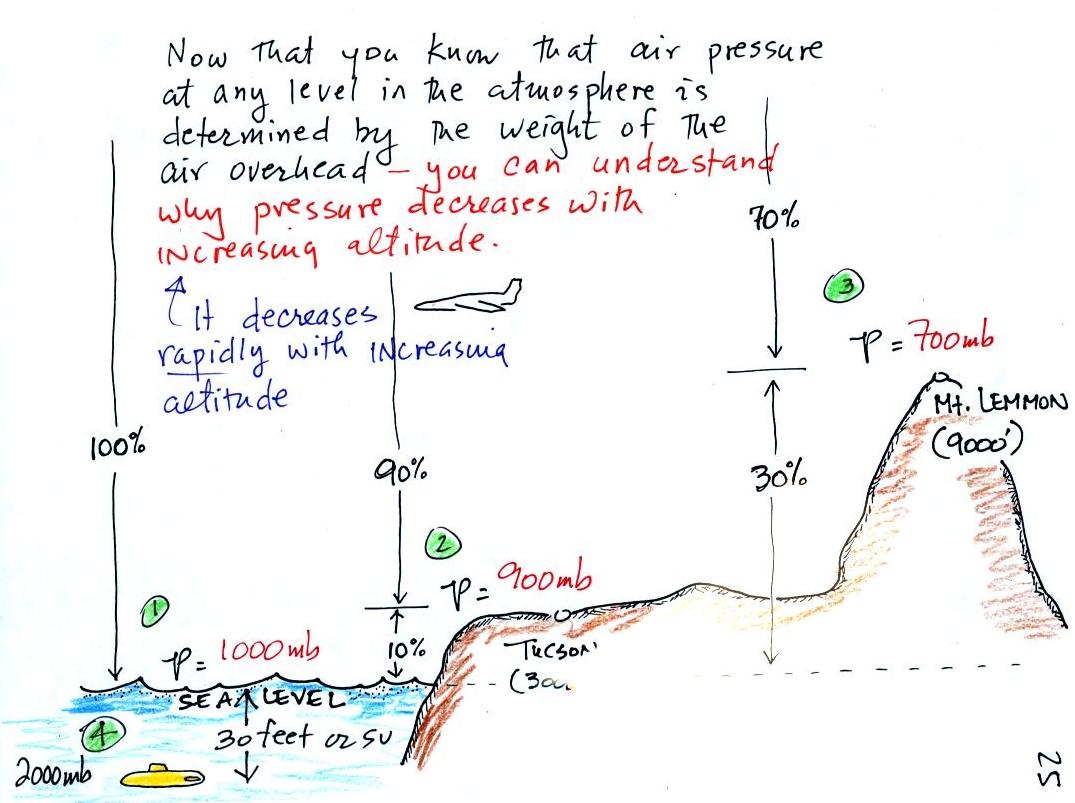

At sea level altitude, at Point 1, the

pressure is normally about 1000 mb. That is

determined by the weight of all (100%) of the air in

the atmosphere.

Some parts of Tucson, at Point 2, are 3000

feet above sea level (most of central Tucson is a

little lower than that around 2500 feet). At

3000 ft. about 10% of the air is below, 90% is still

overhead. It is the weight of the 90% that is

still above that determines the atmospheric pressure

in Tucson. If 100% of the atmosphere produces a

pressure of 1000 mb, then 90% will produce a pressure

of 900 mb.

Pressure is typically about 700 mb

at the summit of Mt. Lemmon (9000 ft. altitude at Point 3) because

70% of the atmosphere is overhead..

Pressure decreases rapidly

with increasing altitude. We will find that

pressure changes more slowly if you move

horizontally. Pressure changes about 1 mb for

every 10 meters of elevation change. Pressure

changes much more slowly normally if you move

horizontally: about 1 mb in 100 km. Still the

small horizontal changes are what cause the wind to

blow and what cause storms to form.

Point

4 shows a submarine at a depth of about 30

ft. or so. The pressure there is determined by

the weight of the air and the weight of the water

overhead. Water is much denser and much heavier

than air. At 30 ft., the pressure is already

twice what it would be at the surface of the ocean

(2000 mb instead of 1000 mb).

I'll try to show a short video segment about what would happen

to a human head if it were taken down to a depth of 10,000

feet in the ocean where the surrounding pressure is

enormous.

I learned about a relatively new sport called free diving

as semester or two ago. Basically divers see how deep

they can go while holding their breath. They must

descend and return to the surface on just a single lungful of

air. It is a very hazardous sport. Here is a link

to an article about a diver that made it to a depth of 236

feet but died upon reaching the

surface. Death was caused by

the high pressure deep under water forcing fluid from

the blood into the diver's lungs.

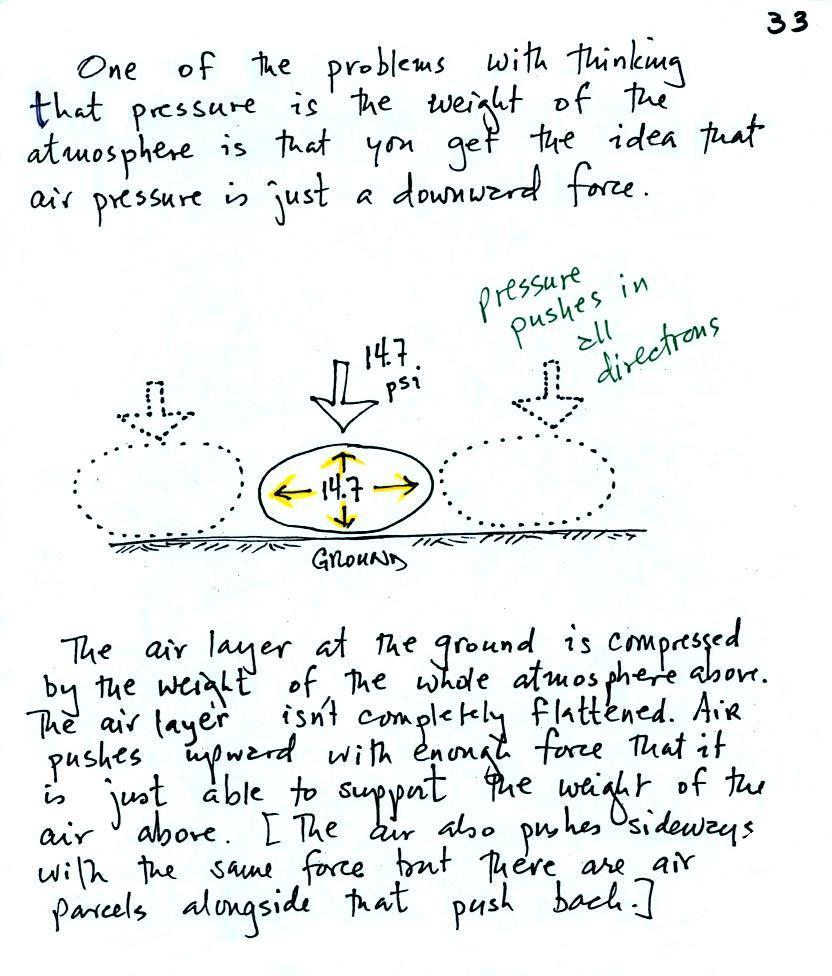

4. The downward force of air pressure

Sea level pressure, 14.7 psi, might not sound like

much. But when you start to multiply 14.7 by all the

square inches on your body it turns into a lot of pounds of

force.

The yellow box on the person's chest in the picture is a brick

size, 4" x 8" = 32 square inch, area. If you multiply

14.7 psi by 32 sq. in. you get 470 pounds! It would take

a stack of 90 to 100 bricks to produce that much weight.

Imagine lying on the beach with 90 bricks stacked up on your

chest.

Why isn't the person in the picture

above crushed by the weight of the atmosphere

above. The answer is that the person's body

pushes back with the same amount of force. Air

does the same thing. This is the topic we will

explore next.

5. The upward (and sideways) force of air pressure

Air pressure is a force that

pushes downward, upward, and sideways. If you fill a

balloon with air and then push downward on it, you can feel

the air in the balloon pushing back (pushing upward).

You'd see the air in the balloon pushing sideways as

well.

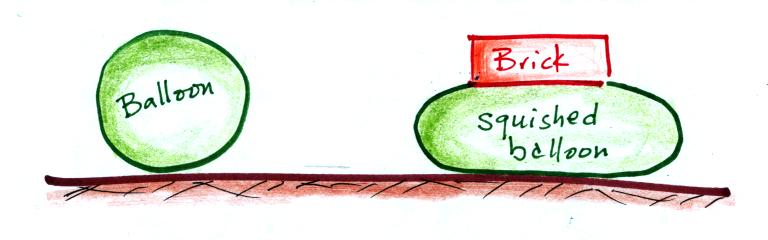

We were able to see this by placing a

brick on top of a balloon. The balloon gets squished

(pushed out sideways) but not flattened. It eventually

pushes upward with enough force to support the brick.

The squished balloon is what air at the bottom of the

atmosphere looks like. And it is supporting more than

just one brick, it is supporting a pile 90 to 100 bricks

tall (just like the yellow box on the chest of the guy at

the beach).

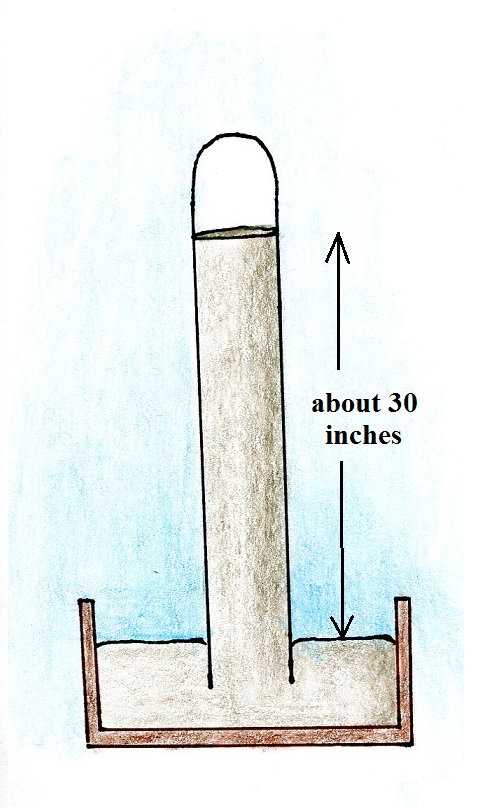

Another helpful

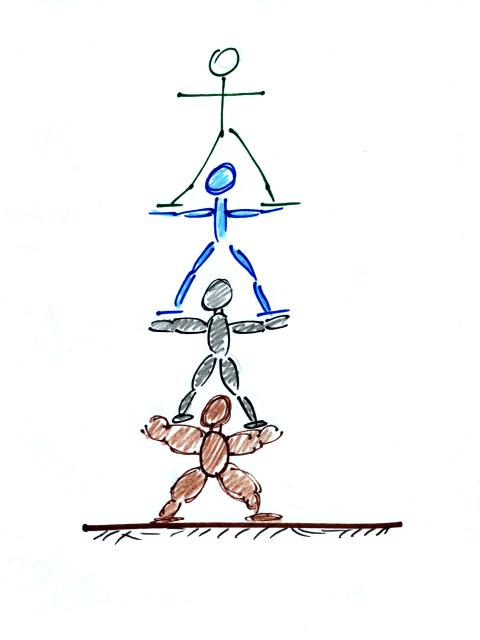

representation of air in the atmosphere might be a

people pyramid.

The people in the figure are like

layers of air in the atmosphere all stacked on top of each

other.

If the bottom person in the stack above were standing on a

scale, the scale would measure the total weight of all the

people in the pile. That's analogous to sea level

pressure being determined by the weight of the all the air

above.

The bottom person in the picture above must

be strong enough to support the weight of all the people

above. The bottom layer of the atmosphere pushes

upward with enough pressure to support the weight of the

air above.

Here's another pretty amazing example of air

pressure pushing upward.

This is my present day car (a 1980 Toyota Celica)

sits on 4 tires, which are really nothing more than

balloons. The air pressure in the four tires

pushes upward with enough force to keep the 1000 or 2000 pound

vehicle off the ground. The air pressure also pushes

downward, you'd feel it if the car ran over your foot.

The air also pushes sideways with a lot of force; tires need

to be strong to keep from exploding or coming off the wheel.

6. Upward Air Pressure force demonstration

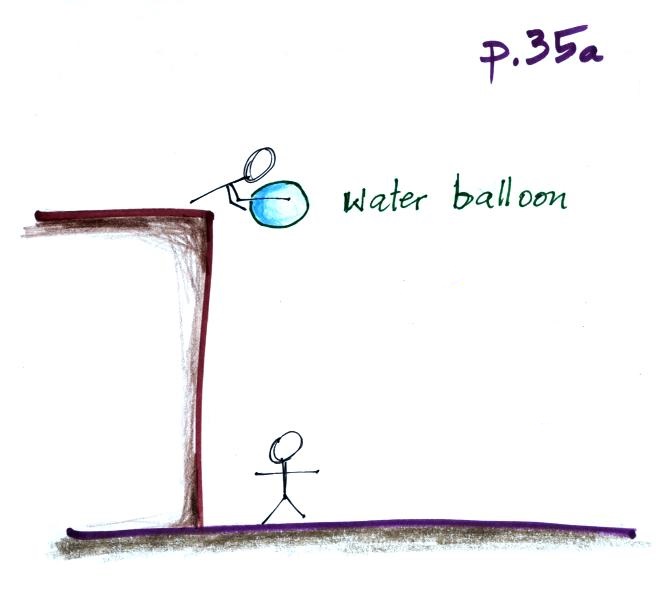

This is a logical point to do a demonstration. A

demo that tries to prove that air pressure really does push

upward as well as downward. Not only that but that the

upward force is fairly strong. The demonstration is

summarized on p. 35a in the ClassNotes.

It's pretty obvious that if you fill a balloon with a

little water and let go it will drop. And most

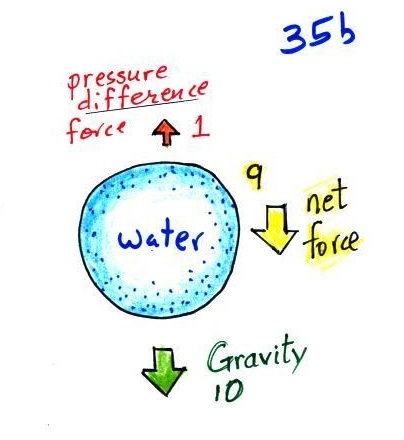

everyone in the class knows why (see below - I broken the

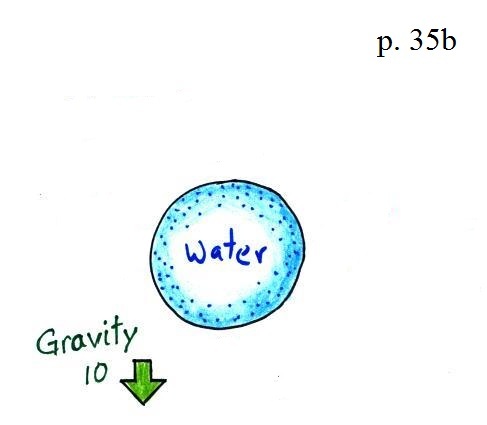

figure on p. 35b into pieces for clarity).

Gravity

exerts a downward force on the balloon. I just

made up a number, 10, to give you some idea of its

strength.

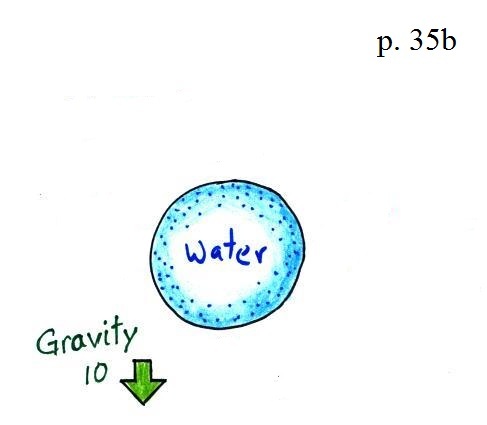

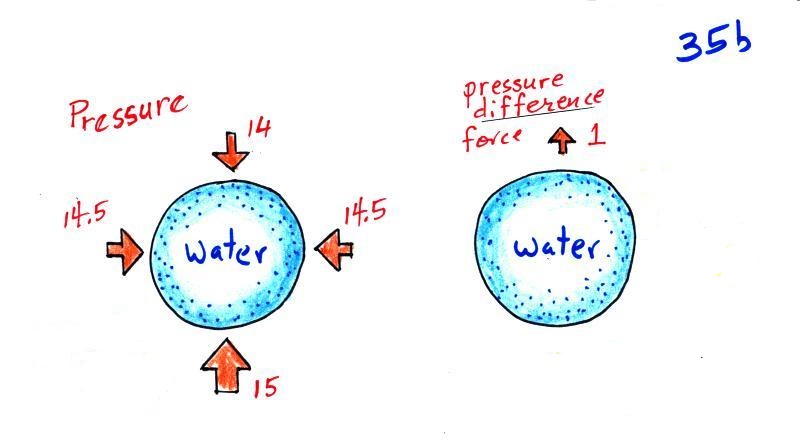

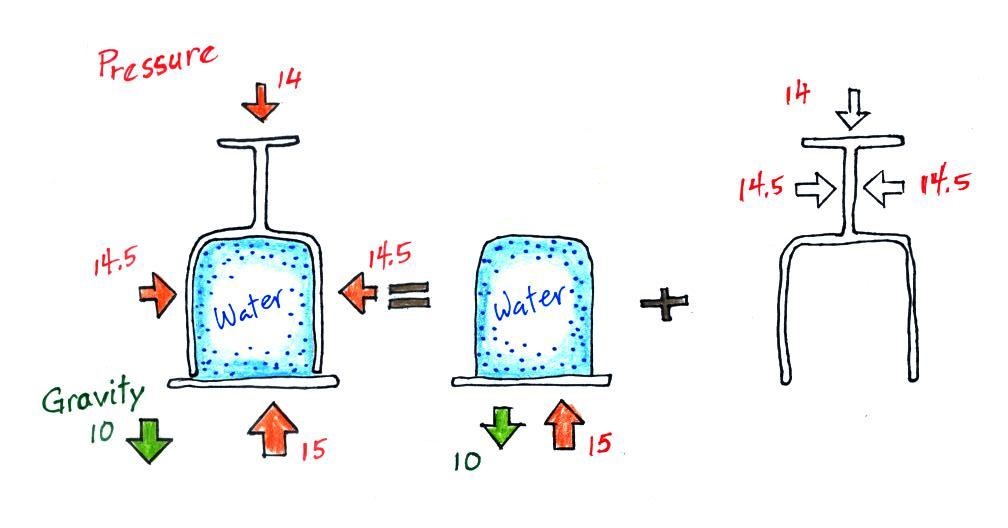

But the picture above isn't quite complete.

The water balloon is surrounded by air that

is pushing upward, downward, and sideways on the

balloon. These pressure

forces are strong but mostly cancel each

other out. The sideways forces do cancel out

exactly.

The up and down forces aren't quite equal because

pressure decreases with increasing altitude. The

upward pointing force at the bottom is stronger (15

units) than the downward force at the top (14

units). They don't cancel and there is a weak upward pressure difference force

(1 unit strong). I'm pretty sure that most people

in the class don't know about this pressure difference

force.

This picture includes

all the forces (gravity and pressure

difference). The downward gravity force is

stronger than the upward pressure difference

force and the balloon falls.

It seems like we could change things

a little bit and somehow keep the upward and

downward pressure forces from working against each

other. That's

what we do in the demonstration.

In

the demonstration a wine glass is filled

with water (about the same amount of

water that you might put in a small

water balloon).

A small plastic lid is used to cover the wine glass (you'll

need to look hard to see the lid in the photo above).

The wine glass is then turned upside and the water does not

fall out.

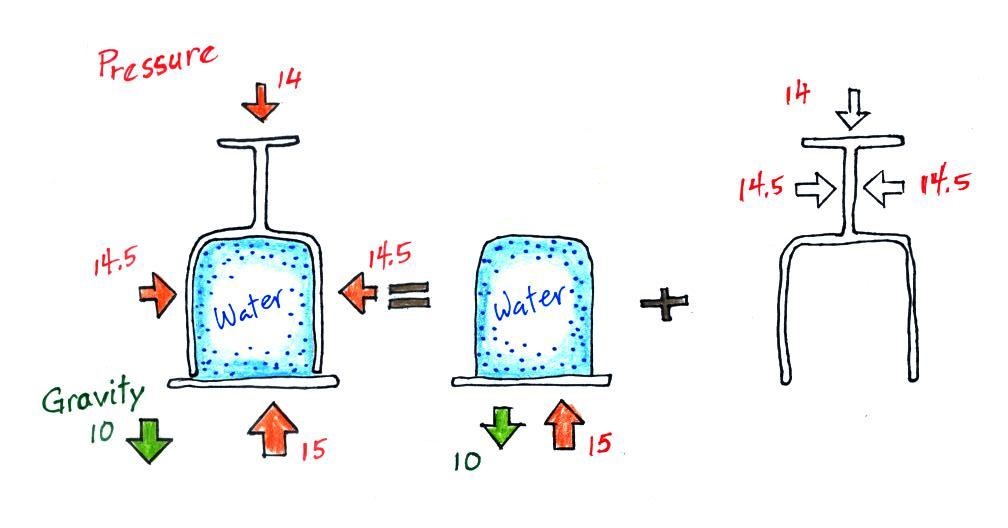

All the same forces are shown again in the left most

figure. We'll split that into two parts - a water and

lid part and an empty glass part.

The 14 units of pressure force is pushing on the glass

now and not the water. I was holding onto the glass,

I'm the one that balanced out this downward pressure force.

Gravity still pulls downward on the water with the same

10 units of force. But with 15 units, the upward

pressure force is able to overcome the downward pull of

gravity. It can do this because all 15 units are used

to overcome gravity and not to cancel out the downward

pointing pressure force.

7. The Magdeburg hemispheres

experiment (sideways pressure force)

Air pressure pushes downward with hundreds of pounds of

force on someone lying on the beach.

The pressure of the air in tires

pushes upward with enough force to keep a 1 ton automobile

off the ground.

What about the sideways air pressure

force?

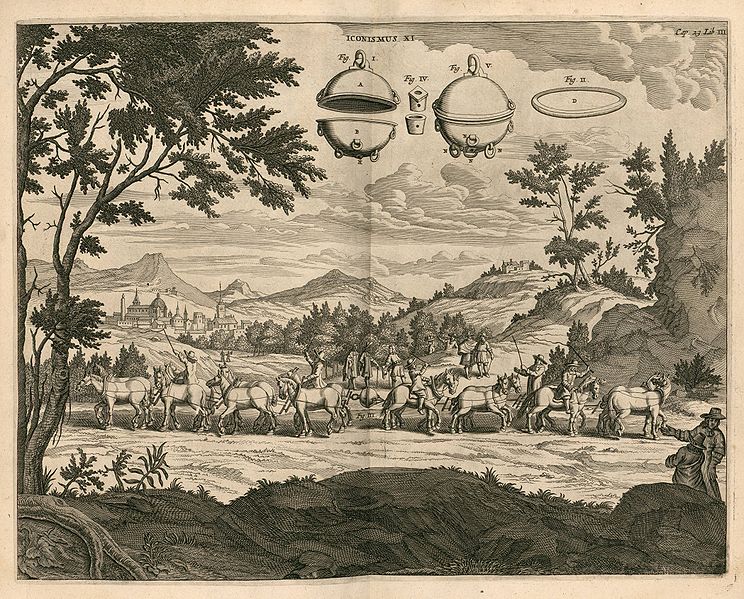

Here's a description of a

demonstration that really needs to be done in Arizona

Stadium at half time during a football game. It

involves Magdeburg hemispheres and two teams of horses

(the following quote and the figure below are from an

article in Wikipedia):

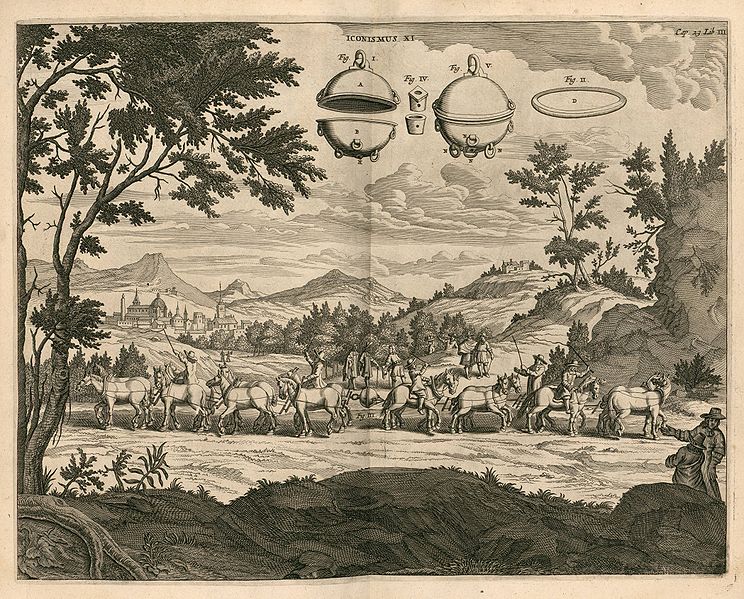

" ... Magdeburg hemispheres

are a pair of large copper hemispheres with mating rims,

used to demonstrate the power of atmospheric pressure.

When the rims were sealed with grease and the air was

pumped out, the sphere contained a vacuum and could not

be pulled apart by teams of horses. The Magdeburg

hemispheres were designed by a German scientist and mayor

of Magdeburg, Otto von Guericke in 1656 to demonstrate the

air pump which he had invented, and the concept of

atmospheric pressure."

Gaspar Schott's sketch of Otto von

Guericke's Magdeburg hemispheres experiment (from the

Wikipedia article referenced above)

It is the pressure of the air

pushing inward against the outside surfaces of the

hemispheres that keeps them together. The

hemispheres appear to have had pretty large surface

area. There would be 15 pounds of force pressing

against every square inch (at sea level) of the

hemisphere which could easily have been several

thousand pounds of total force.

Suction cups work the same way

The suction cup has been pressed against smooth

surface. The cup is flexible and can be pulled away

from the wall leaving a small volume between the wall and

the cup where there isn't any air (a vacuum). There's

no air pressure pushing outward, away from the wall, in the

space between the wall and the suction cup. There's

just pressure from the air surrounding the suction cup that

is pushing and holding it against the wall.

I suspect that if I were to attach the suction cup I had

in class to a white board mounted to a wall and were to ask

a couple of strong people to come down and try to pull it

off the white board they would end up pulling the white

board off the wall. The Facilities Management people

wouldn't appreciate that very much.