Wednesday, March 23, 2016

It seemed like a good time for something from the Buena Vista

Social Club given President Obama's trip to Cuba earlier this

week. Songs on the first line below are from the original

group I believe. The performance at the White House featured

some original and newer members of the group.

Buena Vista Social Club "La Negra

Tomasa" (8:29), "El Cuarto de

Tula" (8:28), "Chan Chan"

(live at Carnegie Hall) (3:22),

Buena Vista

Social Club Orquesta at the White House (Oct. 2015).

A take home Optional

Assignment was handed out in class today. It is

due next Wednesday (Mar. 30) [you should have the assignment

done before coming to class on the due date].

I'll have copies of the assignment with me in class on Friday and

Monday next week.

We'll work through a few of the following humidity

variable example problems in class today. The goal

here is for you to become a little more familiar with the

humidity variables and see what causes them to change value.

Humidity example problem #1

There are 4 humidity variables (mixing

ratio, saturation mixing ratio, relative humidity, and

dew point temperature). Generally I'll give you

values for two of them and you'll need to figure out

values for the other two.

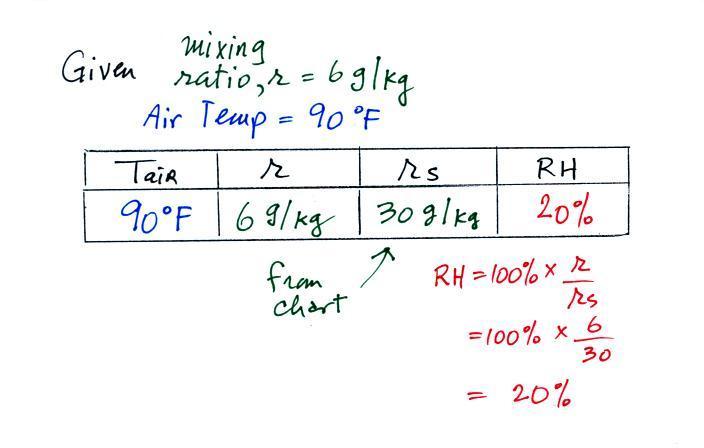

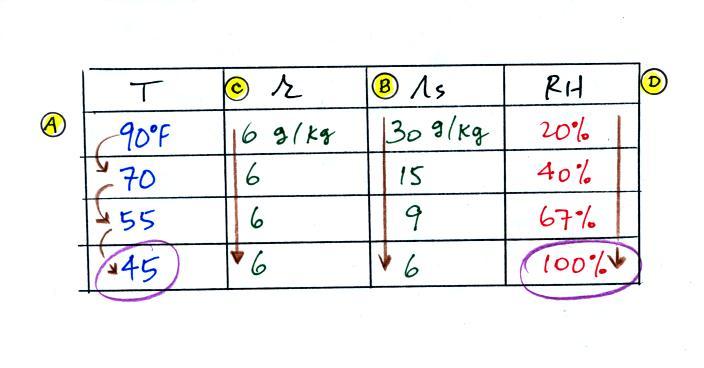

Here are the starting conditions for this first problem

Tair = 90 F

|

r = 6 g/kg

|

RH = ?

|

Td = ?

|

We start by entering the data we were given

Anytime you know the air's temperature you

can look up the saturation mixing ratio value on a chart (such

as the one on p. 86 in the ClassNotes); the saturation mixing

ratio is 30 g/kg for 90 F air. 90 F air could potentially

hold 30 grams of water vapor per kilogram of dry air (it

actually contains 6 grams per kilogram in this example).

Once you know mixing ratio and saturation mixing ratio you

can calculate the relative humidity (you divide the mixing ratio

by the saturation mixing ratio, 6/30, and multiply the result by

100%). You ought to be able to work out the ratio 6/30 in

your head (6/30 = 1/5 = 0.2). The RH is 20%.

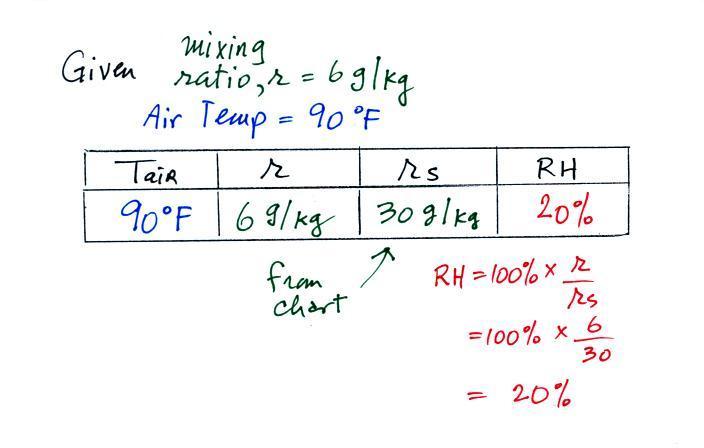

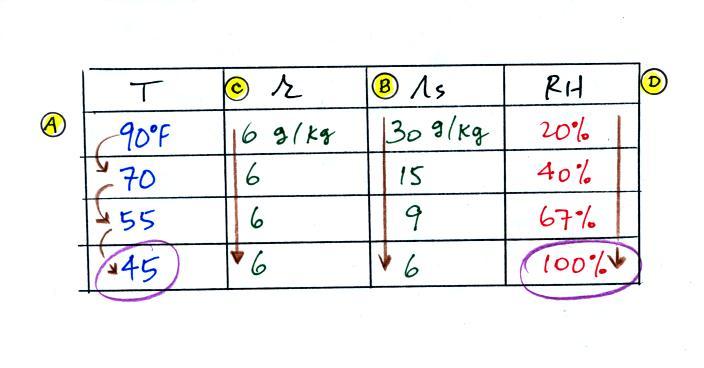

The numbers we just figured out are shown on the top line

below.

(A) To figure out the dew point, we imagine cooling

the air from 90F to 70F, then to 55F, and finally to

45F. Note the effect this has on the mixing ratio, the

saturation mixing ratio and the relative humidity.

(B) At each step we looked up the saturation mixing ratio

and entered it on the chart. Note that the saturation

mixing ratio values decrease

as the air is cooling.

(C) The mixing

ratio (r) doesn't change as we cool the air. The

only thing that changes r is adding or removing water vapor and

we aren't doing either. This is probably the most

difficult concept to grasp.

(D) Note how the relative humidity is increasing as we cool

the air. The air still contains the same amount of water

vapor it is just that the air's capacity is decreasing.

Finally at 45 F the RH becomes 100%. This is the dew

point. The dew point temperature is 45 F

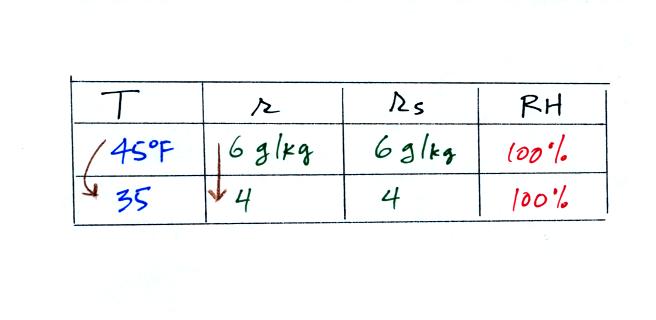

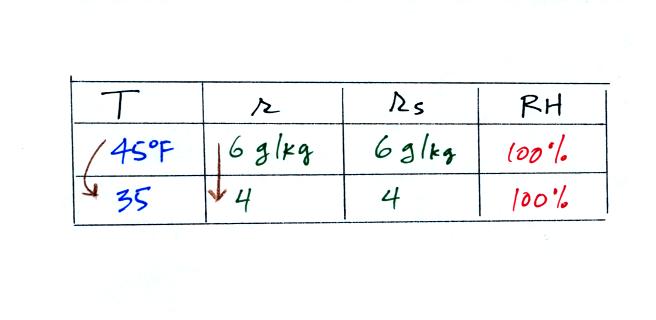

What would happen if we cooled the air below the dew

point temperature?

35 F air can't hold the 6 grams of water

vapor that 45 F air can. You can only "fit" 4 grams of

water vapor into the 35 F air. The remaining 2 grams would

condense. If this happened at ground level the ground

would get wet with dew. If it happens above the ground,

the water vapor condenses onto small particles in the air and

forms fog or a cloud. Because water vapor is being taken

out of the air (the water vapor is turning into water), the

mixing ratio will decrease from 6 g/kg to 4 g/kg. As you

cool air below the dew point, the RH stays constant at 100% and

the mixing ratio decreases.

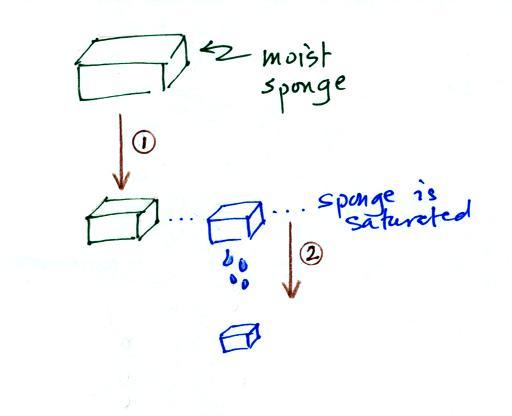

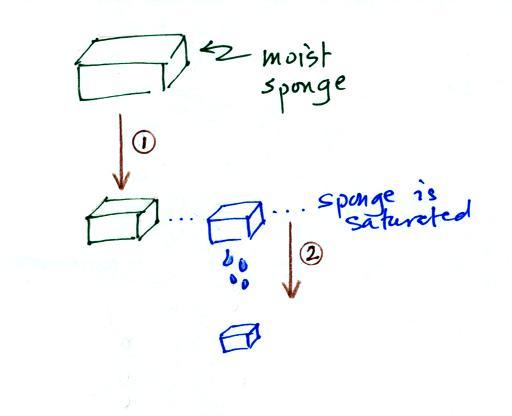

In many ways cooling moist air is liking squeezing a

moist sponge

Squeezing the sponge and reducing its volume

is like cooling moist air and reducing the saturation mixing

ratio. At first (Path 1 in the figure) when you squeeze

the sponge nothing happens, no water drips out. Eventually

you get to a point where the sponge is saturated. This is

like reaching the dew point. If you squeeze the sponge any

further (Path 2) water will begin to drip out of the sponge

(water vapor will condense from the air).

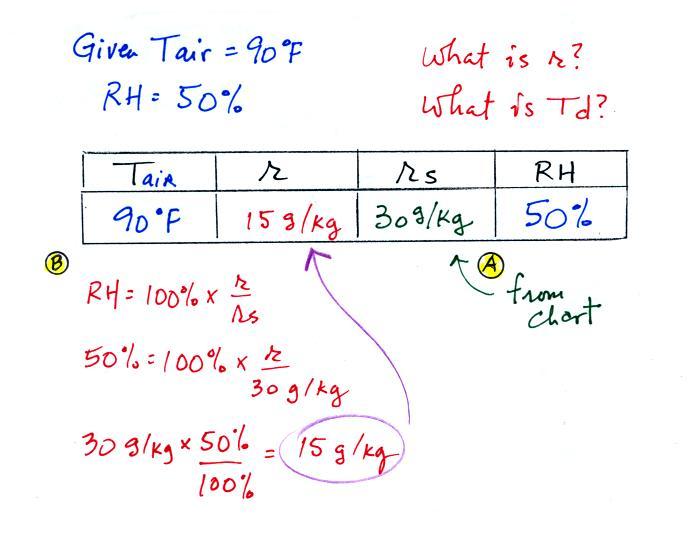

Humidity example problem #2

Tair = 90 F

|

r = ?

|

| RH = 50% |

Td = ?

|

The problem is worked out in detail below

First you fill in the air temperature and the RH data that

you are given.

(A) since you know the air's temperature you can look up the

saturation mixing ratio (30 g/kg).

(B) Then you might be able to figure out the mixing

ratio in your head. Air that could hold up to 30 g/kg of

water vapor is filled to 50% of its capacity. Half of 30

is 15, that is the mixing ratio. Or you can substitute

into the relative humidity formula and solve for the mixing

ratio. The details of that calculation are shown above

at B.

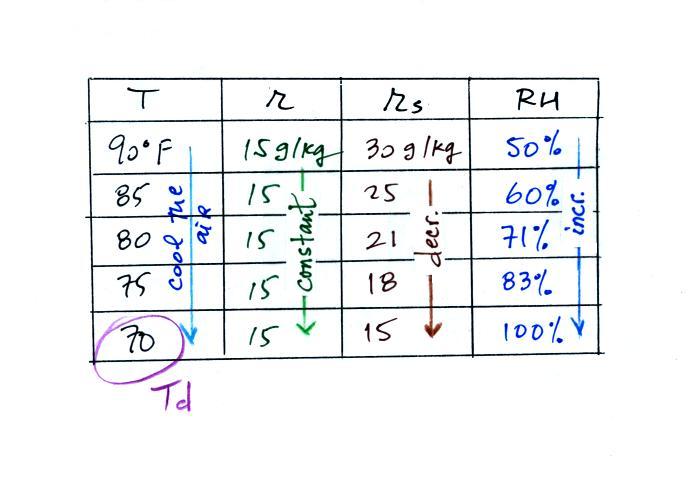

Finally you imagine cooling the air (I

added more intermediate temperatures in the table above

than we did in class). Notice how the

saturation mixing ratio decreases, the mixing ratio stays

constant, and the relative humidity increases as the air is

cooled. In this example the RH reached 100% when

the air had cooled to 70 F. That is the dew point

temperature.

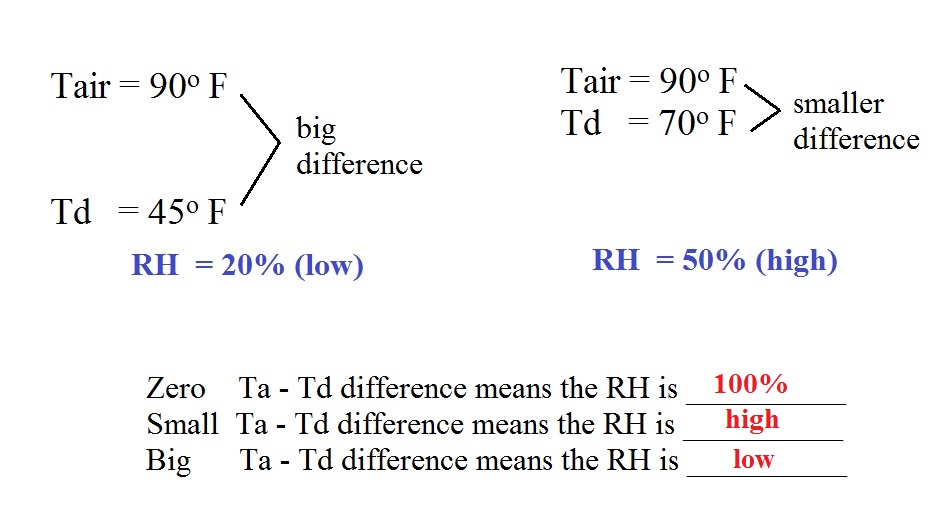

What does

the difference Tair - Td tell you about the

relative humidity?

We

can use results from humidity problems #1 and

#2 to learn and understand a useful

rule.

In the first example the difference between the air and dew

point temperatures was large (45 F) and the RH was low (20%).

In the 2nd problem the difference between the air and dew

point temperatures was smaller (20 F) and the RH was higher

(50%).

The easiest way to remember this rule might be to remember the

case where there is no difference between the air and dew

point temperatures.

The RH then would be 100%.

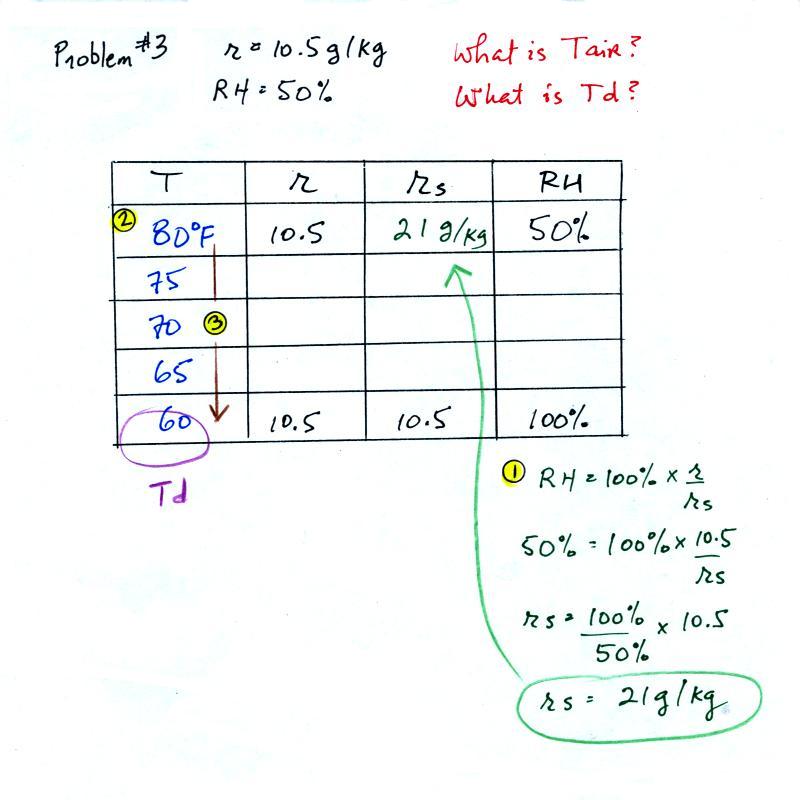

Humidity example problem #3

Tair =

?

|

r = 10.5 g/kg

|

| RH = 50% |

Td = ?

|

We skipped this problem in

class. But I've included all the details

below just in case you want to try to solve the problem on

your own.

You're given the the mixing ratio = 10.5 g/kg and a

relative humidity of 50%. You

need to figure out the air temperature and the dew point

temperature. Here's the play by play solution

to the question:

(1) The air contains 10.5 g/kg of water vapor. This is

50% (half) of what the air could potentially hold. So

the air's capacity, the saturation mixing ratio must be 21

g/kg (you can either do this in your head or use the RH

equation following the steps shown above).

(2) Once you know the saturation mixing ratio you can look up

the air temperature in a table (80 F air has a saturation

mixing ratio of 21 g/kg)

(3) Then you imagine cooling the air until the RH becomes

100%. This occurs at 60 F. The dew point is 60 F

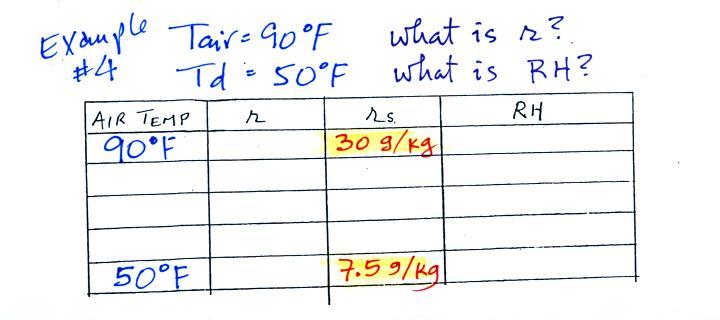

Humidity example problem #4

Tair = 90 F

|

r = ?

|

RH = ?

|

Td = 50 F

|

One of the dew

point's jobs is the same as the mixing ratio - it

gives you an idea of the actual amount of water vapor

in the air. This problem will show that if you

know the dew point, you can quickly figure out the

mixing ratio and vice versa. Knowing the dew

point is equivalent to knowing the mixing ratio.

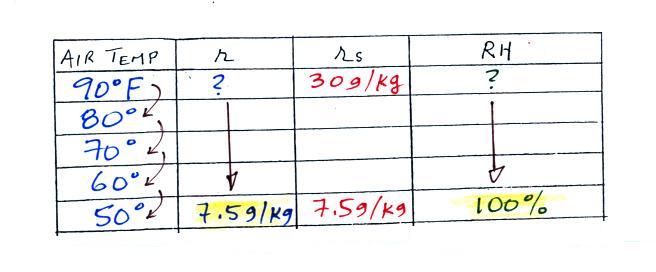

We enter the two temperatures given on a chart and look up the

saturation mixing ratio for each.

We ignore the fact that we don't know the mixing ratio.

We do know that if we cool the 90 F air to 50 F the RH will

become 100%. So on the 50 F row, we can set the mixing

ratio equal to the value of the saturation mixing ratio at 50

F, 7.5 g/kg. The two have to be equal in order for the

RH to be 100%.

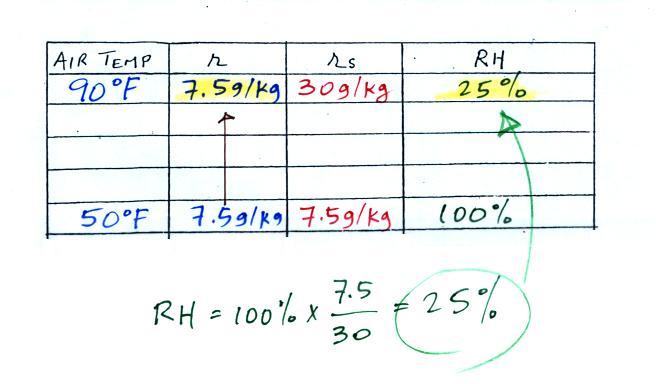

Remember back to the three earlier examples.

When we cooled air to the the dew point, the mixing ratio

didn't change. So the mixing ratio must have been 7.5

all along. Once we know the mixing ratio in the 90

F air it is a simple matter to calculate the relative

humidity, 25%.

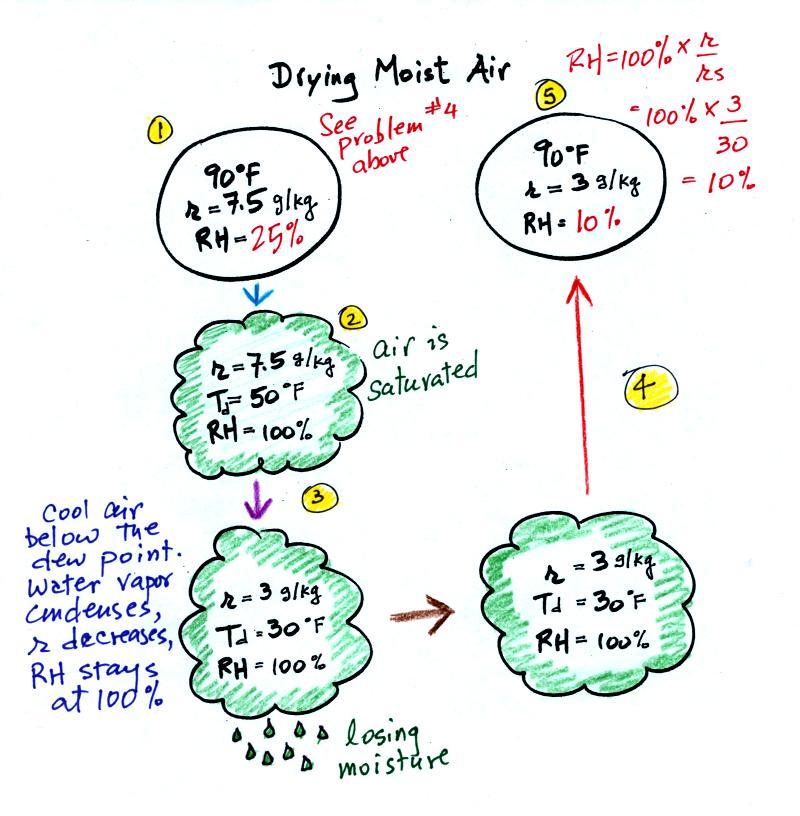

Drying moist air

The figure below is on p. 87 in the photocopied ClassNotes.

It

explains how you can dry moist air.

At Point 1 we start with some 90 F air with a relative

humidity of 25%, fairly dry air. These are the same

numbers that we had in Example Problem #4. We imagine

cooling this air to the dew point temperature, 50 F.

While doing that the mixing ratio, r, would stay

constant. Relative humidity would increase and

eventually reach 100%. A cloud would form (Pt. 2 in the

figure above).

Then we continue to cool the air below the dew point, to 30

F. Air that is cooled below the dew point finds itself

with more water vapor than it can contain. The excess

moisture must condense (we will assume it falls out of the air

as rain or snow). Mixing ratio will decrease, the

relative humidity will remain 100%. When air reaches 30

F it contains 3 g/kg, less than half the moisture that it

originally did (7.5 g/kg).

The air is being warmed back up to 90 F along Path 4. As

it warms the mixing ratio remains constant. Cooling

moist air raises the RH. Warming moist air, as is being

down here, lowers the RH. Once back at the starting

temperature, Point 5, the air now has a RH of only 10%.

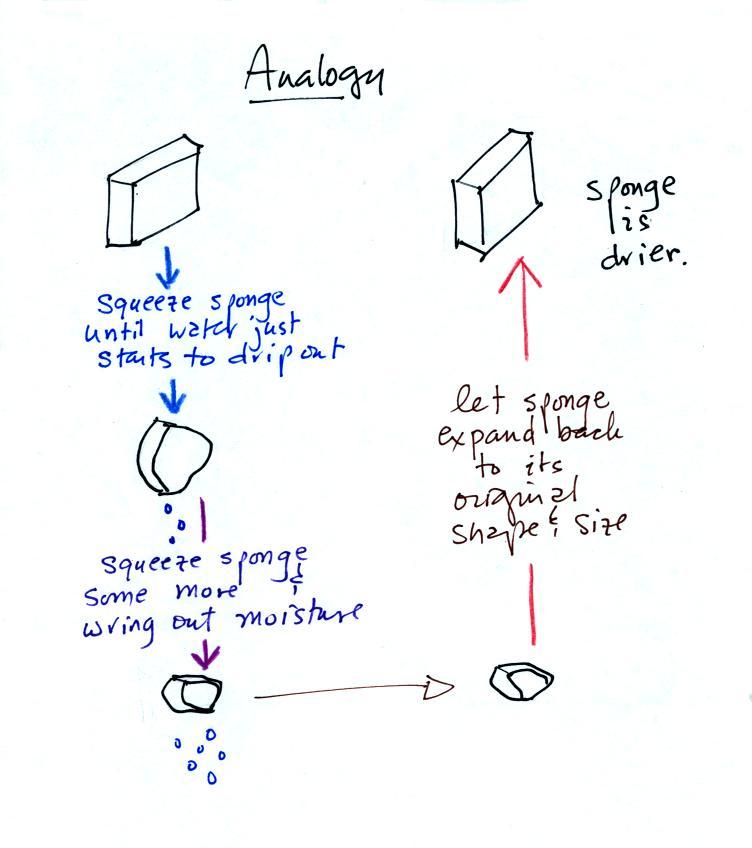

Drying moist air is basically wringing moisture from a wet

sponge.

You start to squeeze the sponge and it gets

smaller. That's like cooling the air and reducing the

saturation mixing ratio, the air's capacity for water

vapor. At first squeezing the sponge doesn't cause

anything to happen (that's like cooling the air, the mixing

ratio stays constant as long as the air doesn't lose any water

vapor). Eventually water will start to drop from the

sponge (with air this is what happens when you reach the dew

point and continue to cool the air below the dew point).

Then you let go of the sponge and let it expand back to its

original shape and size (the air warms back to its original

temperature). The sponge (and the air) will be drier

than when you started.

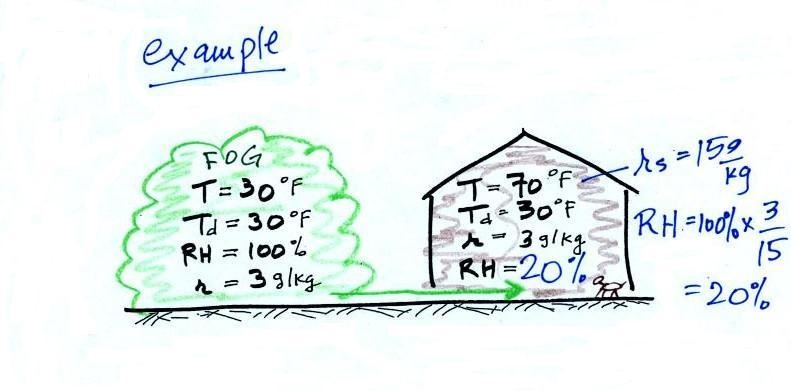

Dry air indoors in the winter

The air indoors in the winter is often quite

dry.

In the winter, cold air is brought inside your

house or apartment and warmed. Imagine foggy 30 F air

(with a RH of 100% this is a best case scenario, the cold air

outdoors usually has a relative humidity less than 100% and is

drier). Bringing the air inside and warming it will cause the

RH to drop from 100% to 20%.. This can cause chapped

skin, can irritate nasal passages, and causes cat's fur to

become charged with static electricity.

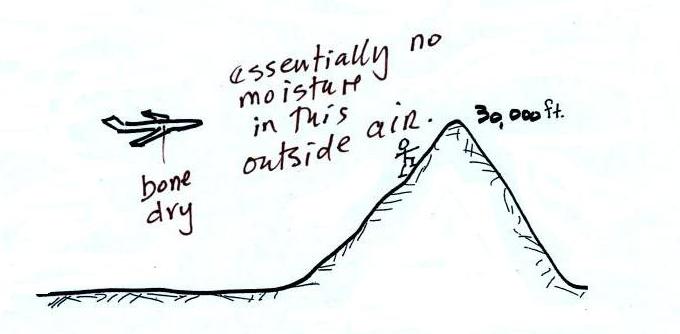

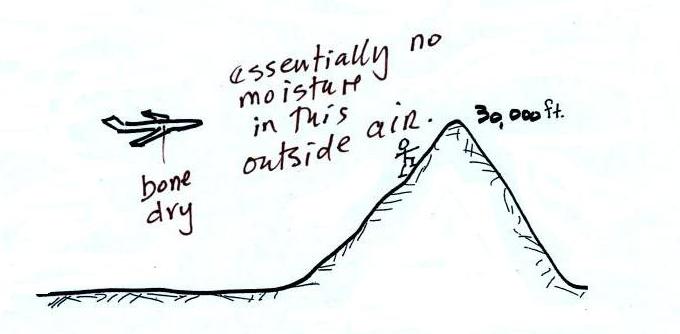

The air in an airplane comes from

outside the plane. The air outside the plane can

be very cold (-60 F perhaps) and contains very little

water vapor (even if the -60 F air is saturated it

would contain essentially no water vapor). When

brought inside and warmed to a comfortable

temperature, the RH of the air in the plane would be

essentially 0%. The RH doesn't get this low

because the airplane adds moisture to the air to make

to make the cabin environment tolerable. Still

the RH of the air inside the plane is pretty low and

passengers often complain of dehydration

on long airplane flights. This

may increase the risk of catching a cold (ref)

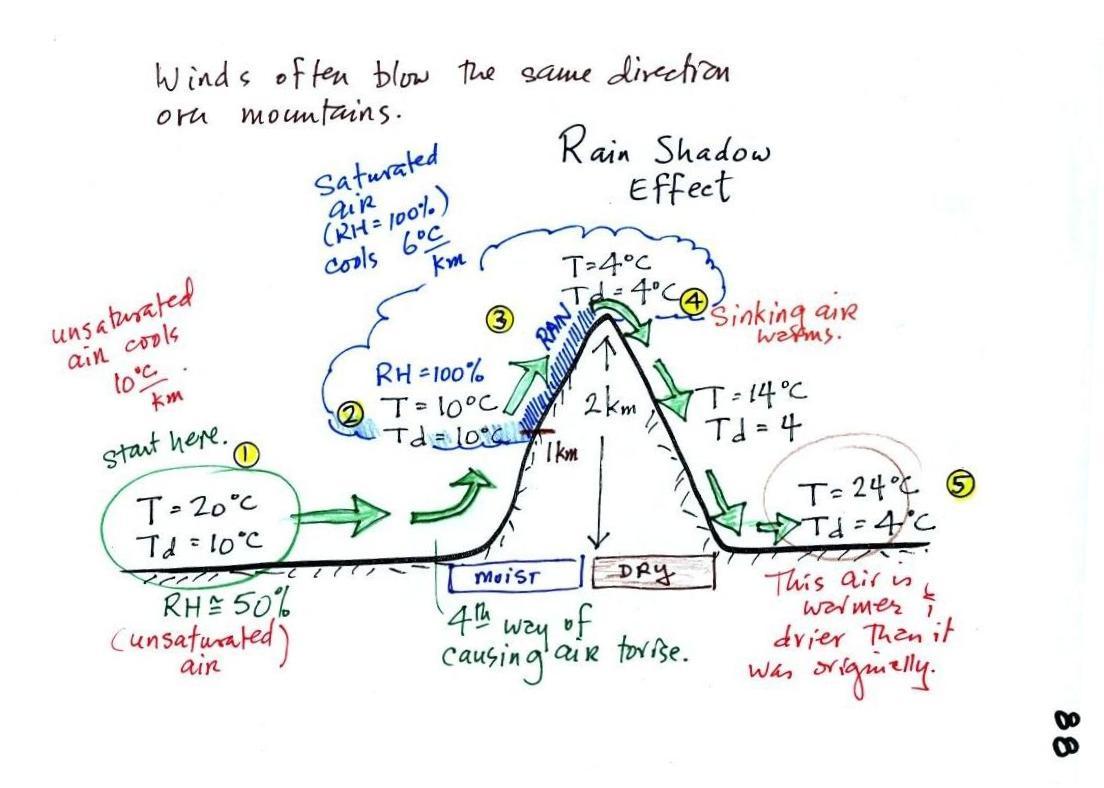

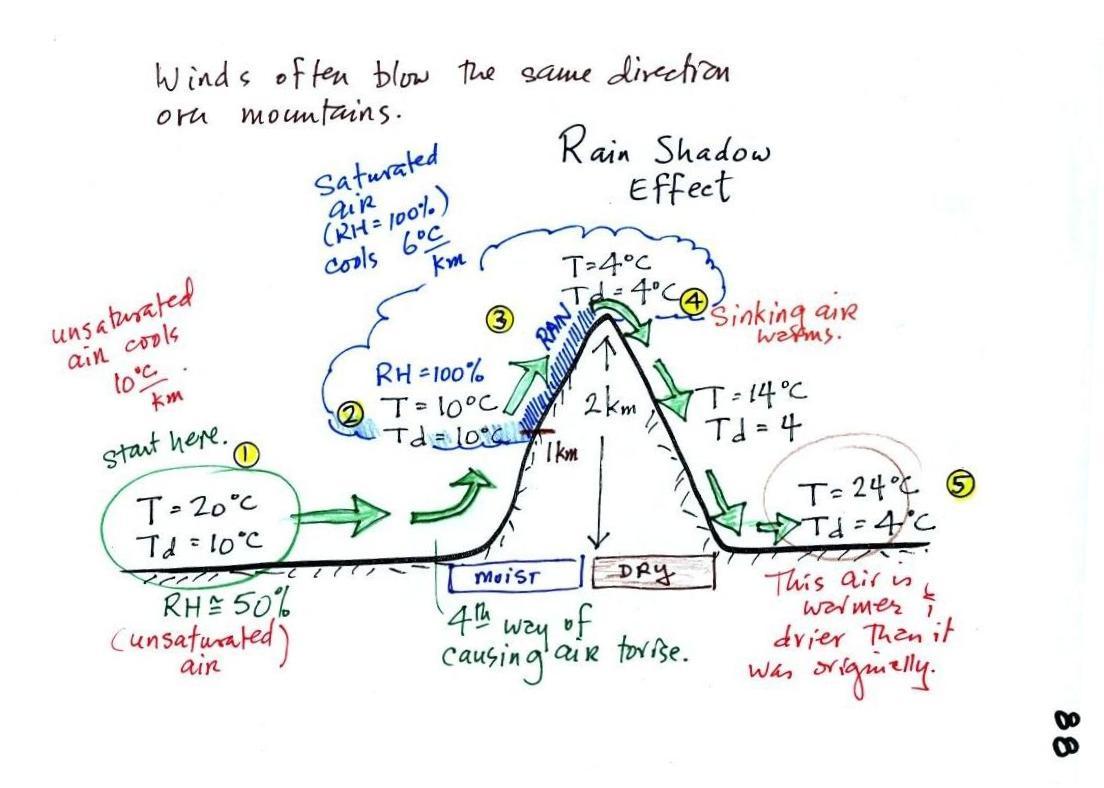

The rain-shadow effect

Next a much more important example of drying moist

air (see p. 88 in the photocopied ClassNotes).

We start with some moist but unsaturated air (the

RH is about 50%) at Point 1 (the air and dew point

temperatures would need to be equal in order for the air

to be saturated).

As it is moving toward the right the air runs into a

mountain and starts to rise*

(see below).

Rising air expands and cools. Unsaturated air cools

10 C for every kilometer of altitude gain (this is known

as the dry adiabatic lapse rate but isn't something you

need to remember). So after rising 1 km the air will

cool to 10 C which is the dew point.

The air becomes saturated at Point 2 (the air temperature

and the dew point are both 10 C). Would you be able

to tell if you were outdoors looking at the

mountain? Yes, you would see a cloud appear.

Now that the RH = 100%, the saturated air cools at a

slower rate than unsaturated air (condensation of water

vapor releases latent heat energy inside the rising volume

of air, this warming partly offsets the cooling caused by

expansion). We'll use a value of 6 C/km (an average

value). The air cools from 10 C to 4 C in next

kilometer up to the top of the mountain. Because the

air is being cooled below its dew point at Point 3, some

of the water vapor will condense and fall to the ground as

rain. Moisture is being removed from the air and the

value of the mixing ratio (and the dew point temperature)

decreases.

At Point 4 the air starts back down the right side of the

mountain. Sinking air is compressed and warms.

As soon as the air starts to sink and warm, the relative

humidity drops below 100% and the cloud disappears.

The sinking unsaturated air will warm at the 10 C/km

rate.

At Point 5 the air ends up warmer (24 C vs 20 C) and drier

(Td = 4 C vs Td = 10 C) than when it started out.

The downwind side of the mountain is referred to as a

"rain shadow" because rain is less likely there than on

the upwind side of the mountain. Rain is less likely

because the air is sinking and because the air on the

downwind side is drier than it was on the upslope side.

This is as far as we got in

class today. I'll probably briefly mention the

two rain shadow effect examples below at the beginning

of class on Friday

*This

is topographic lifting, the 4th of 4 processes that can

cause air to rise. The other three were: convergence

(surface winds spiraling inward toward a low pressure

center will rise), fronts (both warm and cold fronts cause

air to rise), and convection (warm air rises).

|

|

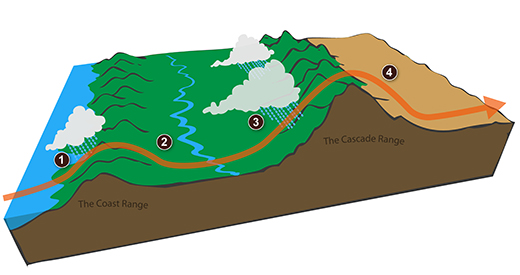

We can see the effects of a rain shadow

illustrated well in the state of Oregon. The figure

above at left shows the topography (here's the source

of that map). Winds generally blow from

west to east across the state.

Coming off the Pacific Ocean the winds first encounter a

coastal range of mountains. On the precipitation map

above at right (source)

you see a lot of greens and blue on the western sides of

the coastal range. These colors indicate yearly

rainfall totals that range from about 50 to more than 180

inches of rain per year. Temperate rainforests are

found in some of these coastal locations. The line

separating the green and yellow on the left side of the

precipitation map is the summit, the ridgeline, of the

coastal mountain range.

That's the Willamette River valley, I think, in between

the coastal range and the Cascades. This valley is

somewhat drier than the coast because air moving off the

Pacific has lost some of its moisture moving over the

coastal range.

What moisture does remain in the air is removed as the

winds move up and over the taller Cascades. The

boundary between yellow/green and the red is the

ridgeline of the Cascade Mountains.

Yearly rainfall is generally less than 20 inches per year

on the eastern side, the rain shadow side, of the

Cascades. That's not too much more than

Tucson which averages about 12 inches of rain a year.

Death valley is

found on the downwind side of the Sierra Nevada

mountains (source of

left image).

The Chihuahuan desert and the

Sonoran desert are found downwind of the Sierra Madre

mountains in Mexico (source

of the right image).

Mexico might

be a little harder to figure out because moist air can move

into the interior of the country from the east and west.

But there are mountains along both coasts, so some of that

moisture will be removed before arriving in the center of the

county.

Most of the year, the air that arrives in

Arizona comes from the west, from the Pacific Ocean (this

changes in the summer). It usually isn't very moist

by the time it reaches Arizona because it has traveled up

and over the Sierra Nevada mountains in California and the

Sierra Madre mountains further south in Mexico. The

air loses much of its moisture on the western slopes of

those mountains. Beginning in early July in

southern Arizona we start to get air coming from the south

or southeast. This air can be much moister and leads

to development of our summer thunderstorms.

Just as some of the world's driest regions are

found on the downwind side (the rain shadow side) of

mountain ranges, some of the wettest locations on earth

are on the upwind sides of mountains. There seems to

be some debate whether Mt.

Wai'ale'ale in Hawaii or Cherrapunji

India gets the most rain per year. Both get

between 450 and 500 inches of rain per year.