Friday, April 29, 2016

Gaelic Storm "Before

the Night is Over" (4:53), "Samurai Set"

(3:50), "Black

is the Colour" (5:32), De Dannan "Hibernian

Rhapsody" (6:48)

A tropical disturbance is just a localized cluster of

thunderstorms that a meteorologist might see on a satellite

photograph. But this would merit observation because of the

potential for further development. Signs of rotation would

be evidence of organization and the developing storm would be

called a tropical depression.

In order to be called a tropical storm the storm must

strengthen a little more, and winds must increase to 35

knots. The storm receives a name at this point.

Finally when winds exceed 75 MPH (easier to remember than 65 knots

or 74 MPH) the storm becomes a hurricane. You don't need to

remember all these names, just try to remember the information

highlighted above.

Generally speaking the lower the surface pressure at the center

of a hurricane the stronger the storm and the faster the surface

winds will blow.

This figure tries to show the relationship between surface

pressure and surface wind speed. The world

record low sea level pressure reading, 870 mb, was set by Typhoon

Tip off the SE Asia coast in 1979. Sustained winds in

that storm were 190 MPH. Three 2005 Atlantic hurricanes:

Wilma, Rita, and Katrina had pressures in the 880 mb to 900 mb

range and winds ranging from 170 to 190 MPH. I

will have to update this figure at some point to include hurricane

Patricia from Fall 2015.

Hurricane features: eye, eye wall, spiral

rain bands

A crossectional view of a mature hurricane (top) and a picture

like you might see on a satellite photograph (below).

Sinking air in the very center of a hurricane produces the

clear skies of the eye, a hurricane's most distinctive

feature. The eye is typically a few 10s of miles across,

though it may only be a few miles across in the strongest

hurricanes. Generally speaking the smaller the eye, the

stronger the storm.

A ring of strong thunderstorms, the eye wall, surrounds the

eye. This is where the hurricane's strongest winds are

found.

Additional concentric rings of thunderstorms are found as you

move outward from the center of the hurricane. These are

called rain bands. These usually aren't visible until you

get to the outer edge of the hurricane because they are covered by

high altitude layer clouds.

Hurricane Katrina making

landfall on Aug. 29, 2005. (source)

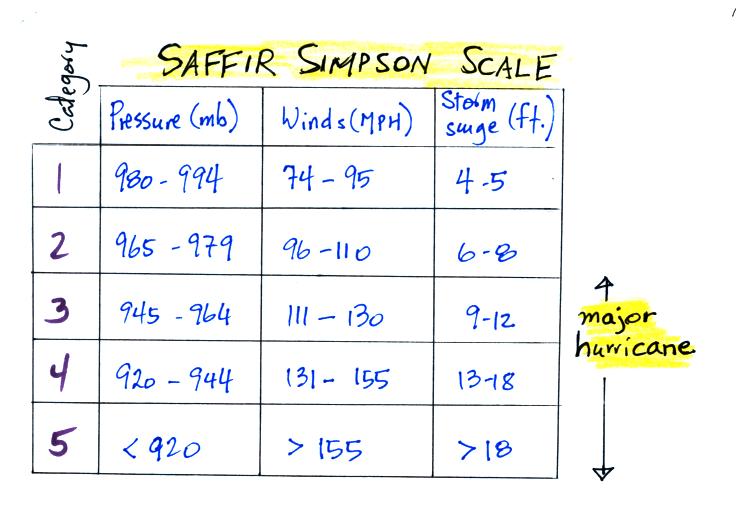

The Saffir Simpson Scale is used to rate

hurricane intensity (just as the Fujita Scale is used for

tornadoes). The scale runs from 1 to 5. Remember that

a hurricane must have winds of 74 MPH or above to be considered a

hurricane. Category 3,4, and 5 hurricanes are considered

"major hurricanes" (in other parts of the world the term super

typhoon is used for category 4 or 5 typhoons).

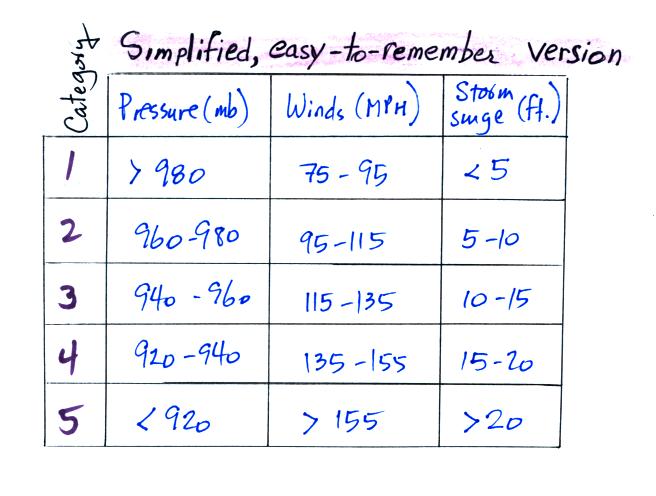

Here's an easy-to-remember

version of the scale

Pressure decreases by 20 mb, wind speeds increase by 20 MPH,

and the storm surge increases by 5 feet with every change in level

on the scale.

Caution: don't get the various scales mixed up

Scale

|

Phenomenon

|

Beaufort

|

Wind speed

|

Fujita

|

Tornado intensity

|

Kelvin

|

Temperature

|

Richter

|

Earthquakes

|

Saffir-Simpson

|

Hurricane intensity

|

Storm surge

The storm surge listed above is a rise in ocean level when a

hurricane makes landfall. This causes the most damage and

the greatest number of fatalities near a coast.

The converging surface winds associated with a hurricane sweep

surface water in toward the center of a hurricane and cause it to

pile up. The water sinks and, in deeper water, returns to

where it came from. This gets harder and harder to do as the

hurricane approaches shore and the ocean gets

shallower. So the piled up water gets deeper and

the return flow current gets stronger.

The National Weather Service has developed the SLOSH computer

model that tries to predict the height and extant of a hurricane

storm surge (SLOSH stands for Sea, Lake, and Overland Surges from Hurricanes). You can see some

animations of SLOSH predictions run for hurricanes of historical

interest (including the Galveston 1900) hurricane at a National

Hurricane Center website (http://www.nhc.noaa.gov/surge)

While watching the animations, you might notice the storm

surge is generally larger on the right hand side of the

approaching hurricane. This is something than can be

explained fairly easily.

In this figure a hurricane with 100 MPH winds is traveling from

east to west at a speed of 15 MPH.

On the north side of the hurricane, the

spinning winds and the motion of the hurricane are in the same

direction and add together. This is where you would

expect to find the strongest winds and the highest storm

surge.