There is quite a bit of variation in the number of Atlantic hurricanes from year to year. This is indicated in figure 9 below, which shows the numbers of major and non-major hurricanes in the north Atlantic Ocean each year from 1944 to 2013. An interesting question is whether or not there is some sort of temporal pattern in the occurrence of Atlantic Hurricanes (pattern of changes in time).

|

| Figure 9: The number of hurricanes in the Atlantic basin each year from 1944 to 2015. Red indicates the number of major hurricanes (category 3 and higher), while blue indicates all hurricanes. |

Although it may be difficult to notice from looking at figure 9, many researchers have concluded that there is a multi-decadal cycle of hurricane activity in the north Atlantic Ocean, consisting of 20 - 40 year periods of increased hurricane activity followed by 20 - 40 year periods of decreased hurricane activity. There is evidence of this cycle in figure 9 above. There appears to have been more and stronger hurricanes from 1944 through the mid to late 1960s, then fewer and less powerful hurricanes from about 1970 through the mid 1990s, then higher numbers of hurricanes again from 1995 through today. You can see that there remains a great deal of variability from year to year though. For example, the north Atlantic Ocean has been in the maximum part of the multidecal cycle since 1995, but this does not mean every year has above average hurricane activity. During the maximum part of the cycle there is a tendency for higher rather than lower hurricane activity, meaning that we expect more high activity than low activity years. The 2005 hurricane season, which was a record-setting year for Atlantic Hurricanes, happened during this period of high activity, but so did the 2013 hurricane season, which had only two hurricanes and no major hurricanes.

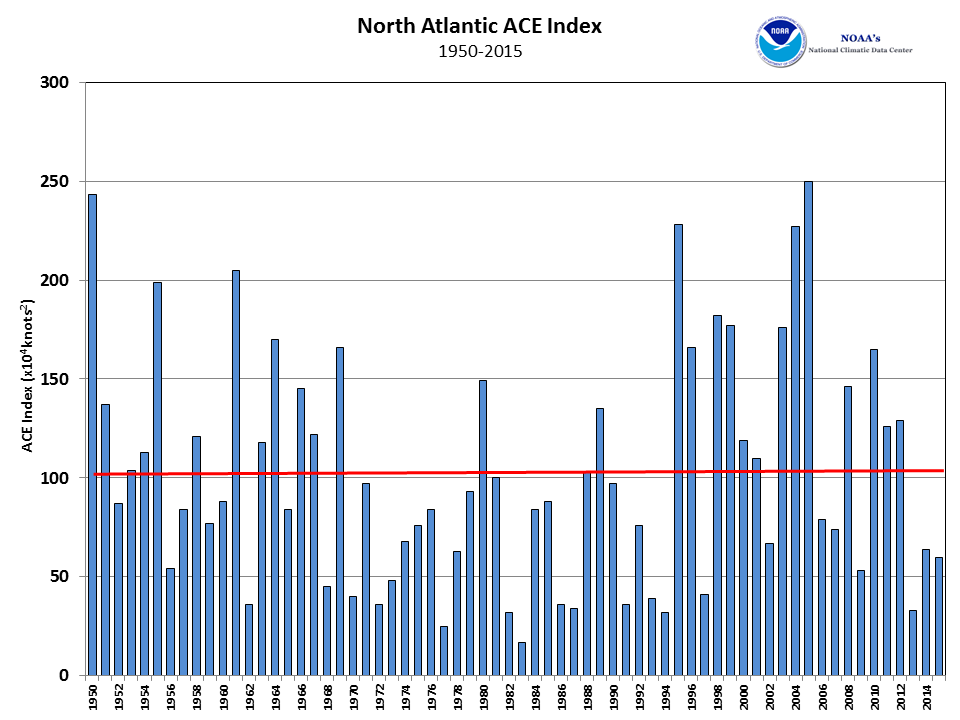

Another piece of evidence is for the existence of a multi-decadal cycle in Atlantic Hurricanes is shown in figure 10 below. The figure presents a metric called Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE). ACE measures the total wind energy realized over the entire life cycle of all storms in a tropical season. ACE factors in storm intensity, frequency, and duration. Put simply, a long-lived very powerful Category 3 hurricane may have more than 100 times the ACE of a weaker tropical storm that lasts for less than a day. The ACE index for each year is determined by adding the ACE values for all storms that formed over that year. As the annual ACE index grows, it indicates that the total wind energy generated by tropical cyclones that year had a great deal of damaging potential. We see generally high annual ACE values during the period from 1950 to 1969, followed by generally annual ACE values from 1970 to 1994, then generally high after 1995. In particular the 2004 and 2005 seasons stand out. Most researchers believe that these trends are significant. The reason for the trend seems to be related to natural fluctuations in the Atlantic sea surface temperature and wind patterns. During active periods, sea surface temperatures are high and wind patterns favor storm development. Based on this information, it is believed that the north Atlantic basin is still in a more active period that began in 1995. However, it has been 20 years since this cycle began and at some point between now and 20 years from now, the cycle is expected to shift to less active hurricane activity in the north Atlantic.

|

| Figure 10: Seasonal Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for the North Atlantic Ocean basin from 1950 - 2015. The red line indicates the average ACE over this period (source NOAA http://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/tropical-cyclones/). |

While variations in the total number of hurricanes in the Atlantic Ocean is interesting, keep in mind that most people only remember the ones that cause death and destruction on the coast. Many Atlantic hurricanes stay out at sea or are relatively weak when they make landfall. Only a small percentage of all North Atlantic hurricanes will make landfall as major hurricanes, categories 3, 4, and 5. The table below shows the number of major hurricanes to strike the US coastline each decade. Interestingly, you can see evidence of the multi-decadal cycle in landfalling major hurricanes. Note the relatively high numbers in the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s (8, 10, and 8 respectively), which corresponds with a high point in the cycle, compared to the relatively low numbers in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s (4, 4, and 4 respectively), which corresponds with a low point in the cycle. The fact that major hurricanes hit the mainland U.S. so infrequently from 1970 to 1990 caused people living during that time to become desensitized to the potential devastion of hurricanes and developed a false sense of security. This desensitization may have played a role in the large number of deaths attributed to hurricane Katrina in 2005 as many coastal residents ignored evacuation orders. There were 7 major landfalling hurricanes in the first decade of the 2000s, which corresponds with another high point in the cycle.

period Number of major landfalling hurricanes

Cat. 3 Cat. 4 Cat.5 Total

1891 - 1900 5 1 6

1901 - 1910 5 1 6

1911 - 1920 3 2 5

1921 - 1930 3 2 5

1931 - 1940 6 1 1 8

1941 - 1950 9 1 10

1951 - 1960 5 3 8

1961 - 1970 4 1 1 6

1971 - 1980 4 4

1981 - 1990 3 1 4

1991 - 2000 3 1 4

2001 - 2010 4 3 7

Interestingly, even though the Atlatic Ocean is currently within an active part of the multi-decadal cycle, the last hurricane to make landfall in the US as a major hurricane was Wilma in 2005. Although Hurricane Sandy was large and destructive, it was classified as a category one hurricane just before it transitioned to a post-tropical cyclone and made landfall in New Jersey. This is the longest stretch without a major landfalling hurricane to hit the United States since at least 1900. It is difficult to ascribe a reason for this other than chance. While this is a trend that most hope will continue, no doubt the US coastline will be hit by major hurricanes in the future. Will it be this year?

Public attention for hurricanes is primarily driven by lanfalling hurricanes that result in death and destruction, rather than fluctuations in the number of hurricanes in the Atlantic or around the globe. In 2004, four hurricanes (three major hurricanes) hit the state of Florida, followed in 2005 by Katrina, the most costly natural disaster in United States history, as well as three other major landfalling hurricanes, Dennis, Rita, and Wilma. In fact, the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season was record-breaking. The 27 named tropical storms broke the old record of 21; 15 of these tropical storms became hurricanes, breaking the old record of 12; 4 hurricanes made landfall over the United States at category 3 or higher breaking the old record of 3 set in 2004. A good summary of the record breaking hurricane season of 2005 is given in the article: 2005: A Hurricane season 'On Edge'. The result is that hurricanes were under public scrutiny. And anytime a weather disaster happens, you can be sure that someone will try to link it to global warming. The debate about a possible link between global warming and hurricanes cooled down as the years following 2005 were not destructive hurricane seasons. The debate has heated up again in the aftermath of hurricane Sandy. Hurricane Sandy Global Warming contains a list of articles that try to connect Hurricane Sandy with global warming. Recently, some have tried to link Typhoon Haiyan, which struck the Philippines in November 2013.

A link between global warming and hurricanes is plausible. The basis for a link to global warming is as follows ... As humans add greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, the average surface temperature of the Earth should increase. Exactly how much and how fast it may warm is a matter for debate. One consequence is that global sea surface temperatures will increase. Measurements do show that the global average sea surface temperature has been generally been increasing since 1900 ... Therefore, since hurricanes feed off warm ocean water, one could argue that global warming will result in more and stronger hurricanes around the globe. No one is making the argument that hurricanes don't happen without global warming, but many, including respected scientists, believe that global warming has made recent hurricanes stronger and more destructive.

While the above argument seems plausible, it cannot be scientifically proven at this time. As mentioned above, any recent increase in Atlantic hurricanes can be better explained as a continuation of the multi-decadal cycle discussed above. The 2004 and 2005 hurricane seasons are not overly abnormal when viewed in the context of hurricane cycles over the last 100 years and beyond. The multi-decadal cycle itself certainly cannot be attributed to global warming. Furthermore, hurricane development requires more than just warm sea surface temperatures -- how are these other development factors influenced by global warming? While we cannot say with certainty that global warming has had no influence on hurricane development, it cannot be scientifically proven that global warming has had a large impact on the 2004 and 2005 hurricane seasons or hurricane Sandy in 2012.

I believe it is misleading to try to explain Katrina (or even the record-breaking 2005 hurricane season) through global warming because there have always been occasional strong hurricanes in the Atlantic basin, some of which impact the United States. How can we be sure that hurricanes like Katrina and Sandy would not have happened without global warming, when similar hurricanes have been observed throughout history? Similar arguments are presented in Hurricane Sandy: Not the Global Warming Bombshell It's Cracked Up to Be. In fact we only have reliable records of Atlantic hurricanes back to about 1900 and good records including satellite observations of hurricanes have only been available for about 50 years. Before global satellite coverage, there are gaps in the historical hurricane record; thus, prior to 50 years ago, even some strong storms that spent their entire lifecycle out at sea, were probably unnoticed. One could easily argue that this is not a long enough record to understand the underlying statistics of strong Atlantic hurricanes because they happen so infrequently. We are going to need many more years of good hurricane observations before we will be able to conclude without doubt that global warming is having a large impact on the intensity of hurricanes ... to be able to rule out the possibility that observed fluctuations in hurricane intensity are not part of a natural climatic cycle or attributable to prior gaps in our observations.

I certainly do not mean to imply that a connection between global warming and hurricane intensity is just wild speculation. There are respected research scientists who are convinced of a strong connection. There have been recent modeling studies that indicate hurricanes will become stronger if sea surface temperatures continue to increase, however, the models are not reality and cannot be used as scientific proof. In fact there are other modeling studies that do not show a strong connection between global warming and hurricanes. There is no doubt that higher sea levels, associated with warming temperatures, will make coastlines more vulnerable to hurricane damage, regardless if the warming is actually caused by human activity or just part of a natural cycle in the Earth's climate system, but this does not address the debate about whether or not hurricanes will become stronger. There are also many respected scientists who do not believe there is a strong connection between global warming and hurricanes, so this issue is far from being settled. The debate concerning this issue will continue ... see for example Hurricanes Have Doubled Due to Global Warming, Study Says dated July 30, 2007 and Warmer Ocean Could Reduce Number of Atlantic Hurricane Landfalls dated January 22, 2008. Based on my study of this issue, the news media is much more likely to report on a possible negative impact of global warming, such as a possible increase in destructive hurricanes, rather than presenting an honest evaluation of all current scientific evidence and uncertainty. A link between global warming and stronger hurricanes is often reported as a fact with no mention of its uncertainty.

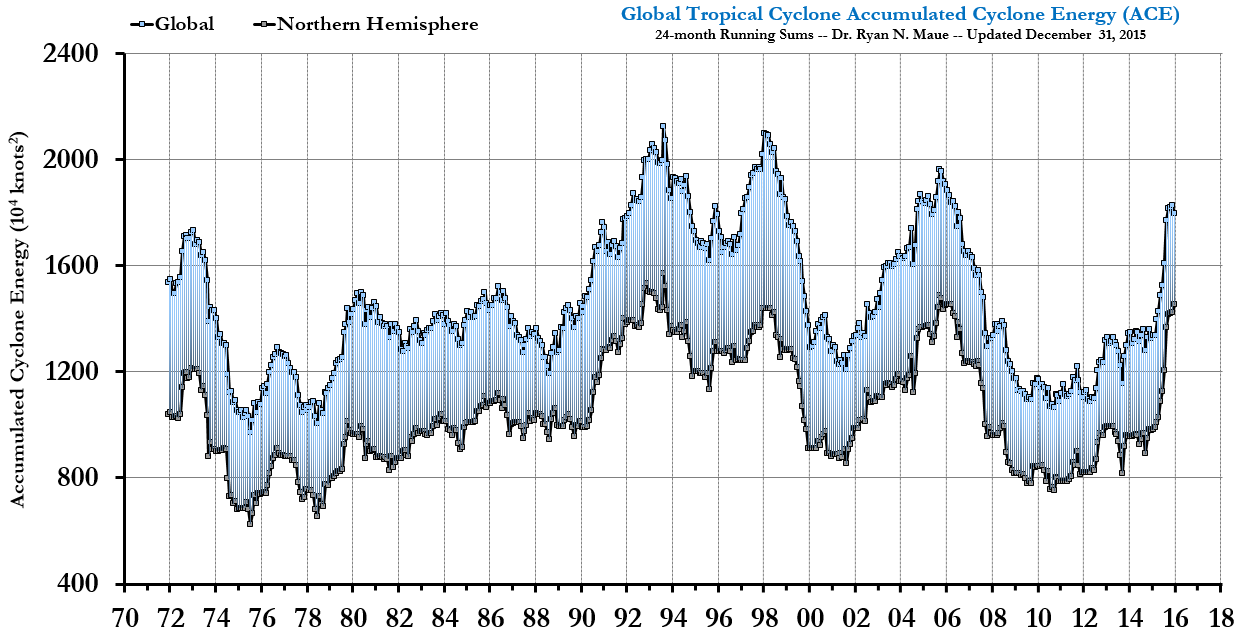

Perhaps the most damaging evidence against a direct link between global warming and hurricane intensity is based on the fact that worldwide (global) ACE values were quite low over the period from 2008 to 2014 (see Figure 11 below) in spite of warmer ocean waters (see also Recent historically low global tropical cyclone activity). Here is a short statement from the author, Dr. Maue: "The perceptible (and perhaps measurable) impact of global warming on hurricanes in today's climate is arguably a pittance (or noise) compared to the reorganization and modulation of hurricane formation locations and preferred tracks/intensification corridors dominated by ENSO (and other natural climate factors). Moreover, our understanding of the complicated role of hurricanes with and role in climate is nebulous to be charitable. We must increase our understanding of the current climate's hurricane activity. An updated figure of global ACE is provided in figure 11 below. Note that global ACE values for 2008 - 2014 were near the lowest in the period of record for global ACE in spite of the fact that global average sea surface temperature was relatively high during this period. You need to realize that figure 11 shows global ACE (all tropical storms in all oceans), while the previous figure of ACE (figure 10 above) was only for north Atlantic Ocean tropical storms. The point is that recent north Atlantic ACE was above average for much of the 2008 - 2014 period mainly because we are in the active phase of the Atlantic Ocean multi-decadal cycle, while global values of ACE are relatively low during that period.

|

| Figure 11: Seasonal global Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index for all ocean basins combined from 1972 - 2015. The black dots are for the Northern Hemisphere only, which accounts for the majority of hurricanes. Each dot represents a 24 month running sum (source WeatherBell, http://models.weatherbell.com/tropical.php). |

Again, while this evidence does not rule out a link between higher sea surface temperatures and hurricane intensity, it does appear that the link is currently weak at best. Through the period of this record, natural variations (or trends) in global ACE are larger than possible variations (or trends) related to increases in sea surface temperature. Note that global ACE was higher in 2015, which may be the start of an increasing trend in global hurricane activity. Only time will tell.

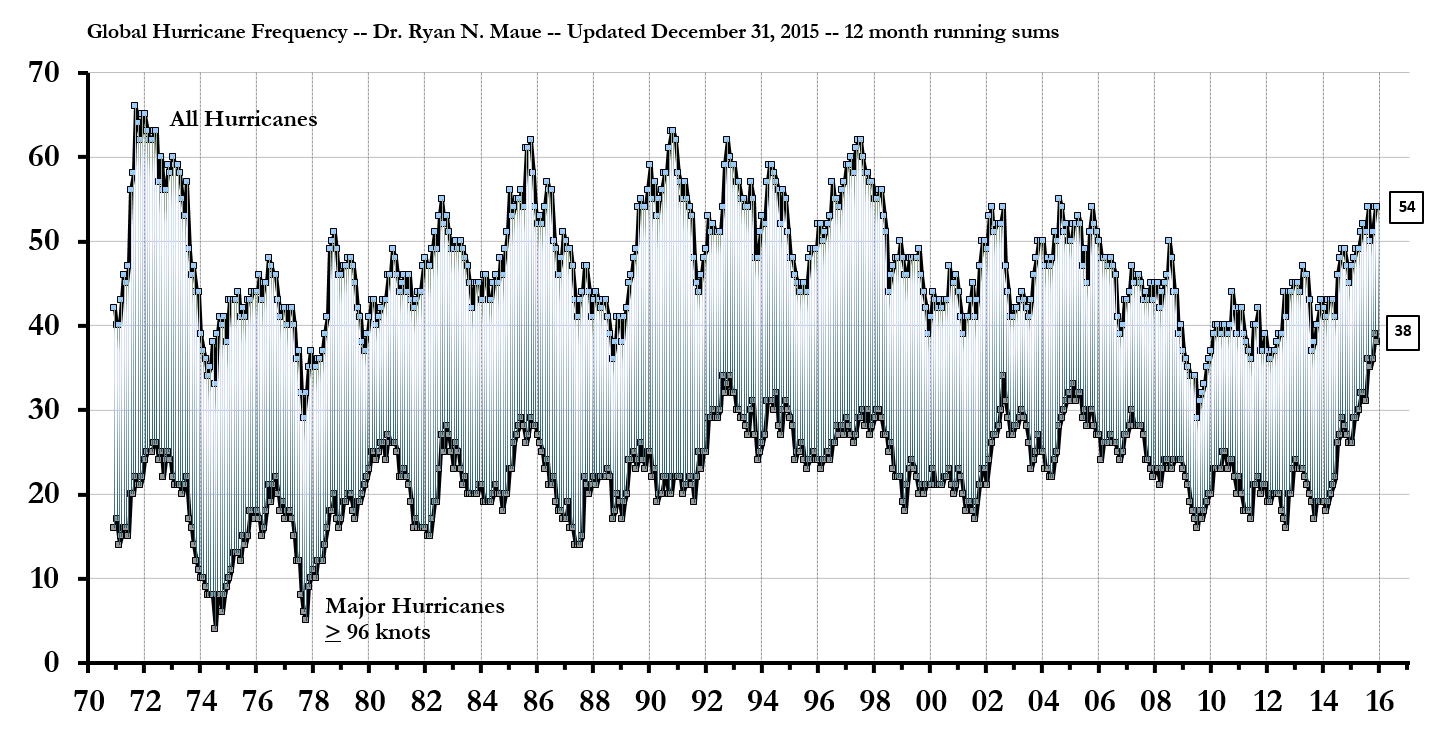

The fact that the many recent years had low activity indicates that the simple predictions by some global warming alarmists, which predicted stronger and more frequent hurricanes following the devastating Atlantic storms of 2004 and 2005, have not happened. However, this evidence does not rule out a link between global warming and more intense hurricanes either. I believe that we can probably say something like this: The impact of global warming on hurricane activity (if there is an impact) in today's climate is probably small compared to the variations of hurricane strength by natural climate factors, i.e., since 1970 the natural variations are much larger than any long-term trend that may be due to global warming. Consider the two figures below. Figure 13 shows the total number of hurricanes and major hurricanes each year from 1970 to 2014, while figure 14 shows the number of global hurricane landfalls each year from 1970 to 2013. There is certainly no obvious indication of a recent trend toward more global hurricanes through the period of this record (since 1970).

|

| Figure 13: Total number of hurricanes and major hurricanes observed over the Earth each year from 1970 through 2015. ( click for reference from Weatherbell.com). |

|

| Figure 14: Total number of landfalling hurricanes observed over the Earth each year from 1970 through 2014 (Link to Reference). |

In spite of the lack of scientific proof, many in the media flock to those who make assertations about influence of global warming on United States hurricanes. See Germany's Environment Minister, Juergen Trittin, cites greenhouse gas emissions as cause for Katrina. In my opinion, the German minister (among others) is using the Katrina weather disaster to further his agenda to reduce emissions of greenhouse gases for fear of global climate change. While this may be a noble agenda, he should base his arguments on sound scientific evidence, not scare tactics. Furthermore, one of the reasons often given as to why we must act immediately to prevent the devastating consequences of continued human-caused global warming is that tropical storms will become more powerful and perhaps more common. This is often reported as if it were a fact, not a theory. You should realize that recent observations do not clearly support this theory.

Arguments for and against a link between global warming and increased hurricane intensity are summarized in this short video segment produced during the 2005 hurricane season by PBS: Is global warming making hurricanes more intense?

Much of the material presented in this section is taken from

Normalized Hurricane Damage in the United States: 1900-2005

authored by Pielke, Jr. et al., published in Natural Hazards Review, Vol. 9, No. 1, February 1, 2008.

A summary of their work, taken from the paper's abstract is provided below:

After more than two decades of relatively little Atlantic hurricane activity, the past decade saw

heightened hurricane activity

and more than $150 billion in damage in 2004 and 2005.

This paper normalizes mainland U.S. hurricane damage from 1900-2005 to 2005 values ...

A normalization provides an estimate of the damage that would occur if storms from the past made

landfall under another year's societal conditions. Our methods use changes in inflation

and wealth at the national level and changes in

population and housing units at the coastal county level. Across both normalization methods,

there is no remaining trend of increasing

absolute damage in the data set, which follows the lack of trends in landfall frequency or

intensity observed over the twentieth century.

The 1970s and 1980s were notable because of the extremely low amounts of damage compared to other

decades. Instructor's note: This is an important point. If we only compare post 1995 Atlantic

hurricanes with the period from 1970-1995, essentially ignoring historical hurricane seasons prior

to 1970, then how can we be certain that activity since 1995 has been abnormally high ... perhaps

the 1970 through 1995 period had abnormally low activity.

The decade 1996 to 2005

has the second most damage among the past 11 decades, with only the decade 1926 to 1935 surpassing its costs.

The most

damaging single storm is the 1926 Great Miami storm, with $140-157 billion of normalized damage:

the most damaging years are 1926

and 2005. Of the total damage, about 85% is accounted for by the intense hurricanes

Saffir-Simpson Categories 3, 4, and 5 , yet these

have comprised only 24% of the U.S. landfalling tropical cyclones.

The study normalizes property damages over the years by making three major adjustments: one to account for inflation, one for growth in wealth (to account for fact that people generally have more "stuff" today as compared to the past and the real value of all this "stuff" has increased), and one to account for overall population growth along affected coastlines. It is very important to consider all three adjustments. Several past works have only considered the inflation adjustment and end up with a plot like figure 3 (from Pielke 2008), which shows that even after adjusting for inflation, total property loses in the US from tropical cyclones continues to follow an upward trend through 2005. However, this is very misleading, since much of the increased costs can be attributed to increases in wealth and population density. Some have even used a plot like figure 3 as evidence that global warming is resulting in stronger hurricanes in the US.

The US coastal populations are certainly more vulnerable to property damage today compared to

past times due to the rapid population increases, especially along the "warm weather coasts"

(see figure 2, Pielke 2008), as well as the tendency for building more lavish structures on the

coasts. After considering these factors, Pielke finds no trend with time in the absolute damage

caused by US landfalling hurricanes. The following summary and warning for the future is taken

from the conclusion:

it

should be clear from the normalized estimates that while 2004

and 2005 were exceptional from the standpoint of the number of

very damaging storms, there is no long-term trend of increasing

damage over the time period covered by this analysis. Even Hurricane

Katrina is not outside the range of normalized estimates for

past storms. The analysis here should provide a cautionary warning

for hurricane policy makers. Potential damage from storms is

growing at a rate that may place severe burdens on society. Avoiding

huge losses will require either a change in the rate of

population growth in coastal areas, major improvements in

construction standards, or other mitigation actions. Unless such

action is taken to address the growing concentration of people and

properties in coastal areas where hurricanes strike, damage will

increase, and by a great deal, as more and wealthier people

increasingly inhabit these coastal locations.

There need to be discussions about whether or not we as a society should continue to build-in and populate hurricane prone areas. Given that people desire to live right on warm water coasts and the very high short-term value available to investors and politicians, it would seem very unlikely to me that we as a society will stop building new and more lavish structures on coastlines that are vulnerable to hurricanes. Another possibility is to regulate through building codes that all structures be able to withstand the worst possible hurricane, but this is quite costly as well. We will probably have to accept that hurricanes will cause major property damage from time to time. One thing that should not be ignored is that urban areas on coastlines should not become so densely populated and congested that evacuations in a reasonable time become impossible. Urban planners need to have reliable evacuation plans.

Should hurricane damaged areas be rebuilt? Who should pay for the rebuilding? Current practice is for the federal government to reimburse people for their losses due to natural disasters. Thus most rebuild in the same disaster-prone area. In a sense the federal government encourages people to rebuild at a large cost to taxpayers. My opinion is that government should not outlaw building in hurricane prone areas, but the people that build in these areas have to assume the risks involved, that is, find private insurance or risk losing everything, i.e., don't expect to be bailed out with tax money. On the other hand, there are those who believe hurricane damages should be a shared public risk assumed by all taxpayers.

A more recent paper, Historical Global Tropical Cyclone Landfalls by Jessica Weinkle, Ryan Maue, and Roger Pielke Jr. comes to the same conclusions with respect to trends in worldwide tropical cyclone damage, i.e., economic damage from tropical cyclones has increased sharply in recent decades, and this can be explained by societal changes, not by changes in the frequency or intensity of tropical storms. Here is the abstract from the paper: "In recent decades, economic damage from tropical cyclones (TCs) around the world has increased dramatically. Scientific literature published to date finds that the increase in losses can be explained entirely by societal i changes (such as increasing wealth, structures, population, etc) in locations prone to tropical cyclone landfalls, rather than by changes in annual storm frequency or intensity. However, no homogenized dataset of global tropical cyclone landfalls has been created that might serve as a consistency check for such economic normalization studies. Using currently available historical TC best-track records, we have constructed a global database focused on hurricane-force strength landfalls. Our analysis does not indicate significant long-period global or individual basin trends in the frequency or intensity of landfalling TCs of minor or major hurricane strength. This evidence provides strong support for the conclusion that increasing damage around the world during the past several decades can be explained entirely by increasing wealth in locations prone to TC landfalls, which adds confidence to the fidelity of economic normalization analyses." The link to the article may not work if you using a computer outside of the University of Arizona network.

Although tropical storms and hurricanes are on average responsible for more economic damage per year in the US than any other type of severe weather, in general they have been responsible for relatively small numbers of deaths in recent decades compared with the early decades of the 1900s. The explanation for the decreasing trend in deaths is simple ... In the early part of the century before satellite imagery and sophisticated forecasting methods, people had little warning of an approaching hurricane, and many were killed. In fact the Galveston, TX hurricane of 1900 still ranks as the most deadly in U.S. history with from 8 to 12 thousand deaths. In modern times, people are warned of an approaching storm and either evacuate or make necessary preparations.

Of course, Katrina was the exception to this trend. Katrina forces us to reconsider the long-held belief that hurricanes will not cause many deaths in the United States because we have such a great hurricane monitoring system and no storm will catch anyone by surprise. Sure property damage was high, but we have come to expect that. The question here is Even with the ample warning provided by the National Hurricane Center, why did so many people die as a result of Katrina? Last count is over 1300 confirmed deaths. This is the most deaths related to a single hurricane since 1928. There are several reasons for the large loss of life from Katrina. Undoubtedly the vulnerability of the New Orleans area to levee failure and flooding was a strong contributing factor and had Katrina hit somewhere else there would have been less loss of life. However, the biggest contributing factor was the decisions made by many people to ignore evacuation warnings and remain home for the storm. The National Hurricane Center's forecasts made 72 hours prior to Katrina making landfall were almost perfect.

Yes, federal and local government screwed up in their response to the disaster, but the only sure way to save lives is for people to evacuate before the storm hits. One reason heard over and over from survivors is that they did not leave because they didn't think things could get that bad. This reaction is probably due to the several factors: (1) major hurricanes don't strike very often; (2) many residents were either new to the gulf coast or never experienced a major hurricane before; (3) some had stayed and lived through other hurricanes, thinking that they are no big deal; and (4) some had evacuated for previous storms that may have missed their house or turned out to be not that severe, so they refused to leave this time. I am sure we can come up with some others. In my opinion, individuals need to educate themselves and make responsible decisions for themselves, their families, and anyone else who relies on them. People living in hurricane prone areas need to understand the devastion that hurricanes can cause, keep informed on hurricane activity in their area, and be prepared to make intelligent decisions. People in New Orleans had the additional responsibility to understand the vulnerability of their city to the possibility of levee breaks whenever a major storm is near. On the other hand, others believe that government should take on more of the responsibility to make sure that people evacuate.

Unfortunately, a Katrina-type disaster was foreseen by many people. In fact a New Orleans newspaper published an article in 2001 about a devasting senario very close to what actually happened. Others just warned about how the people living in hurricane-prone areas seemed unware of the potential damage that can occur when major hurricanes make landfall and would not take appropriate action. Quoting the sumarizing statement from a report generated by the National Hurricane Center (which was prepared prior to the 2004 and 2005 monster hurricane seasons):

"In virtually every coastal city of any size from Texas to Maine, the present National Hurricane Center Director, Max Mayfield, has stated that the United States is building toward its next hurricane disaster. The population growth and low hurricane experience levels of many of the current residents, form the basis for this statement. The areas along the United States Gulf and Atlantic coasts where most of this country's hurricane related fatalities have occurred are also now experiencing the country's most significant growth in population. This situation, in combination with continued building along the coast, will lead to serious problems for many areas in hurricanes. Because it is likely that people will always be attracted to live along the shoreline, a solution to the problem lies in education, preparedness and mitigation.

The message to coastal residents is: Become familiar with what hurricanes can do, and when a hurricane threatens your area, increase your chances of survival by moving away from the water until the hurricane has passed! Unless this message is clearly understood by coastal residents through a thorough and continuing preparedness effort, disastrous loss of life is inevitable in the future."

We can be otpimistic about the well organized and rather smooth evacuations that took place before the powerful Hurricane Ike struck in 2008, which in large part was due to the memory of Katrina. In the near future I do not think we will see a hurricane death toll in the US like Katrina. Even though hurricane Sandy was responsible for over 100 deaths in the US, few of these deaths resulted from people not taking the storm seriously, as was the case for Katrina. However, if we go through another slow period in Atlantic hurricanes, like 1970-1995, will people again forget how potentially deadly hurricanes can be?