Tuesday Oct. 2, 2007

The 2nd Optional Assignment was collected in class today.

I forgot to hand out the 3rd Optional Assignment (some people picked it

up at the end of the period). It isn't due until next Tuesday so

you can pick up a copy in class on Thursday. Copies are also

available in PAS 588.

The Experiment #2 reports and the revised

Expt. #1 reports are due next Tuesday. Expt. #2 doesn't take long

to perform. Collect your data, return your materials this week,

and pick up the supplementary information sheet.

We are making pretty good progress

on grading the 1S1P reports. Some of the reports were

returned in class today

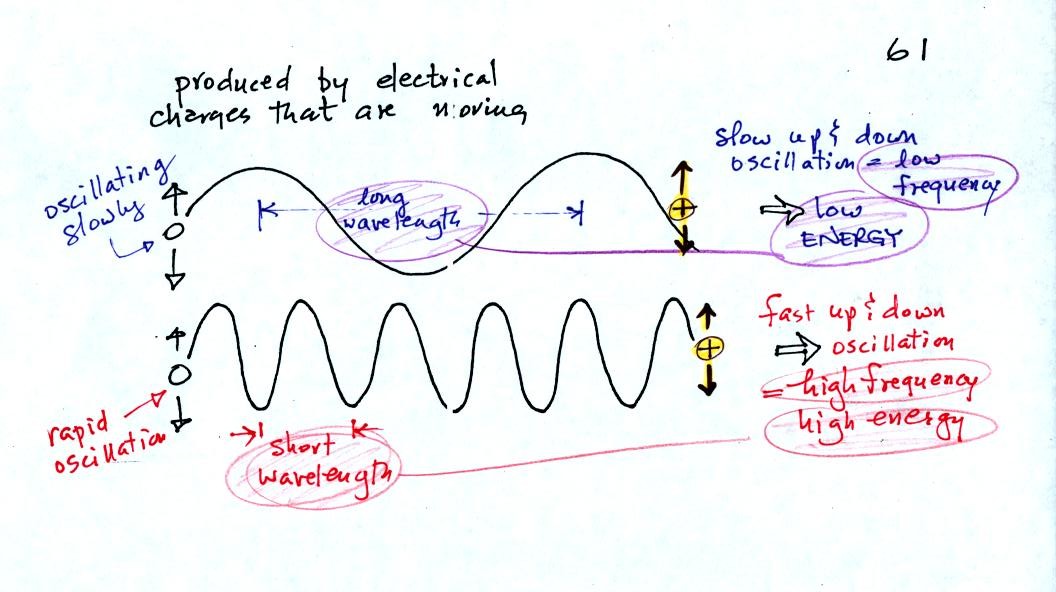

We quickly

reviewed the discussion of electromagnetic radiation found at the end

of last Thursday's notes.

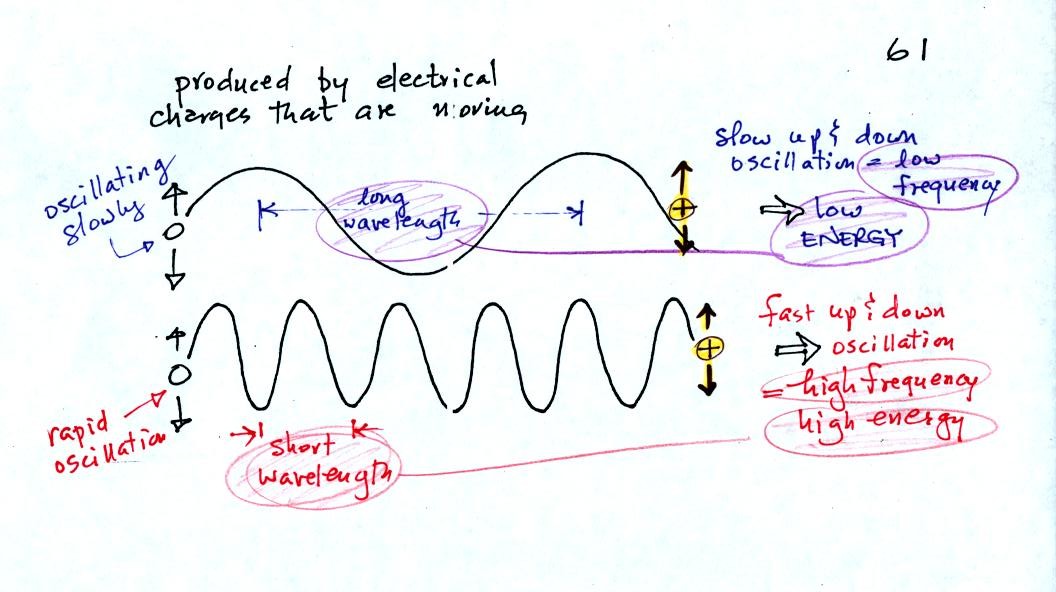

EM radiation is created when you cause a charge to move up

and down.

If you move a charge up and down slowly (upper left in the

figure above) you would produce long wavelength radiation that would

propagate out to the right at the speed of light. If you move the

charge up and down more rapidly you produce short wavelength radiation

that propagates at the same speed.

Once the EM radiation encounters the charges at the right side of the

figure above the EM radiation causes those charges to oscillate up and

down. In the case of the long wavelength radiation the charge at

right oscillates slowly. This is low frequency and low energy

motion. The short wavelength causes the charge at right to

oscillate more rapidly - high frequency and high energy.

The characteristics long wavelength - low frequency - low energy go

together. So do short wavelength - high frequency - high energy.

Note that the two different types of radiation both propagate at the

same speed.

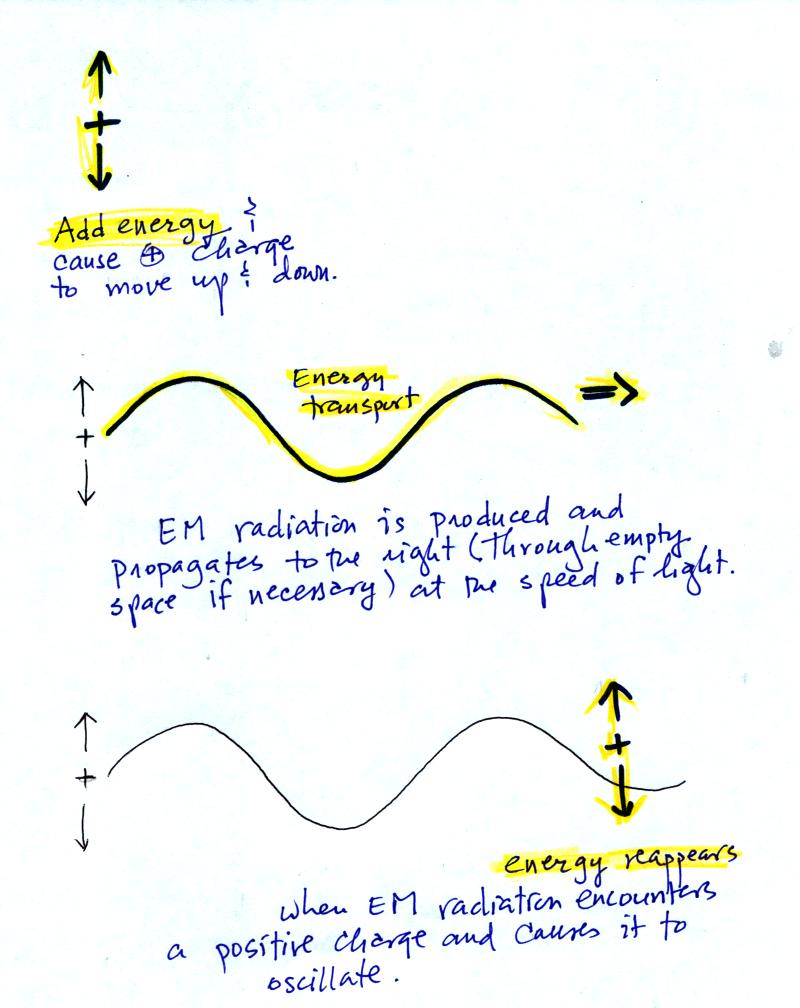

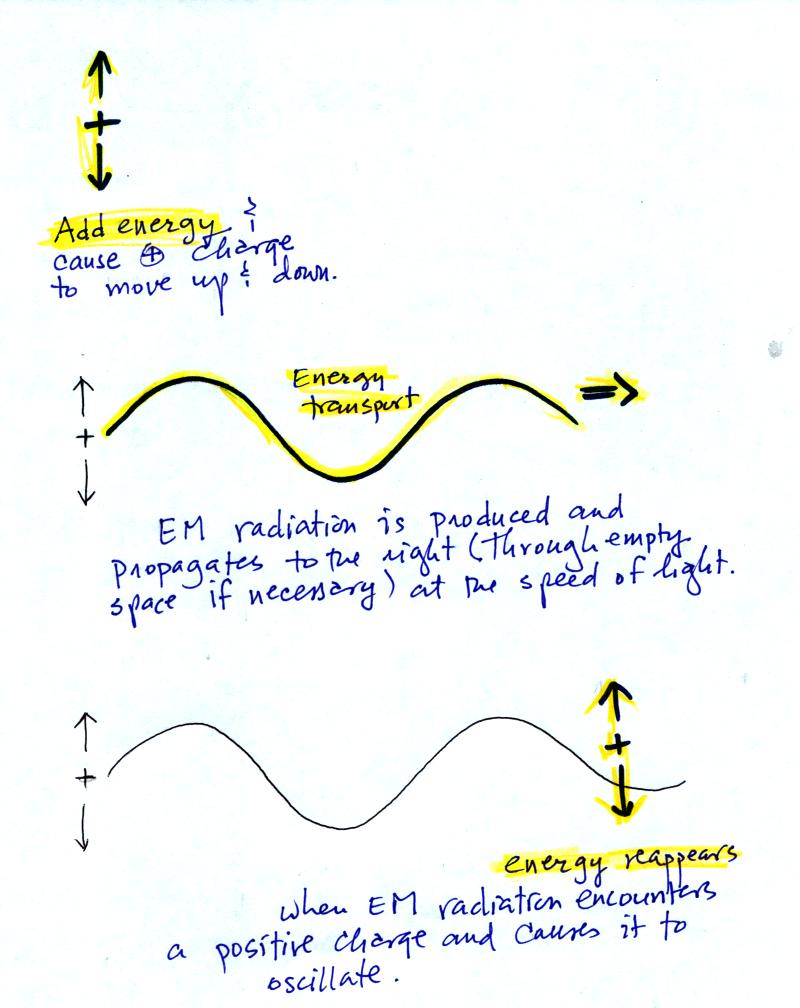

The figure above starts to give you an idea of how energy is

transported from one place to another by electromagnetic radiation.

You add energy when you cause an electrical charge to move up and

down

and create the EM radiation (top).

In the middle figure, the EM

radiation then travels out

to the

right (it could be through empty space or through something like the

atmosphere).

Once

the EM radiation encounters an electrical charge at another location

(bottom right),

the energy reappears as the radiation causes the charge to move.

Energy

has been transported from left to right.

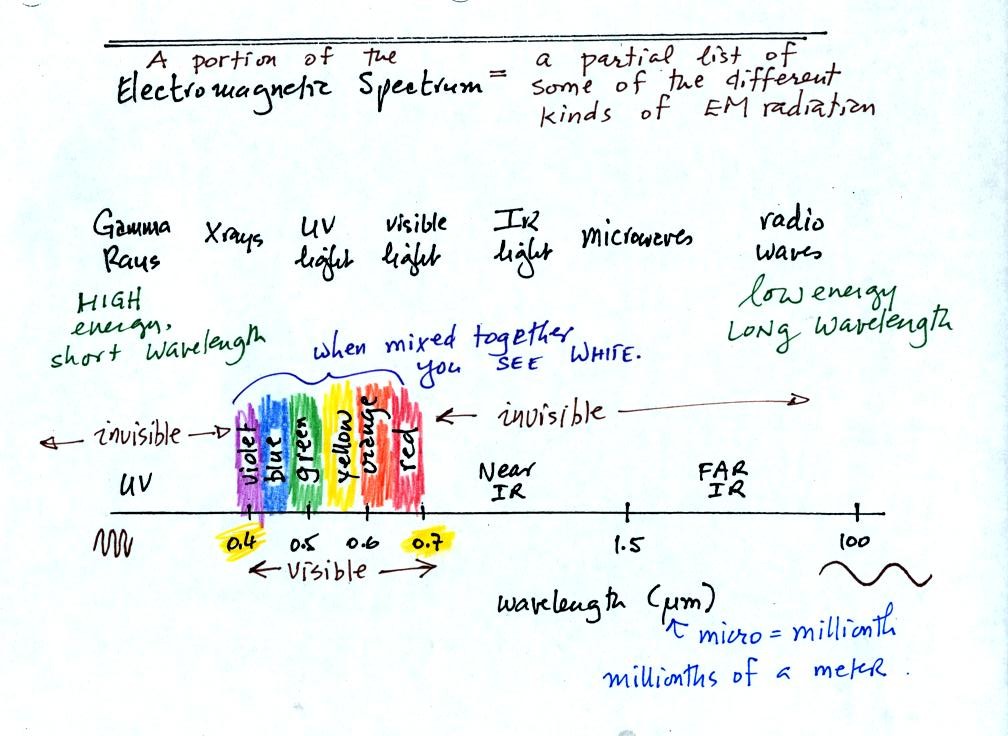

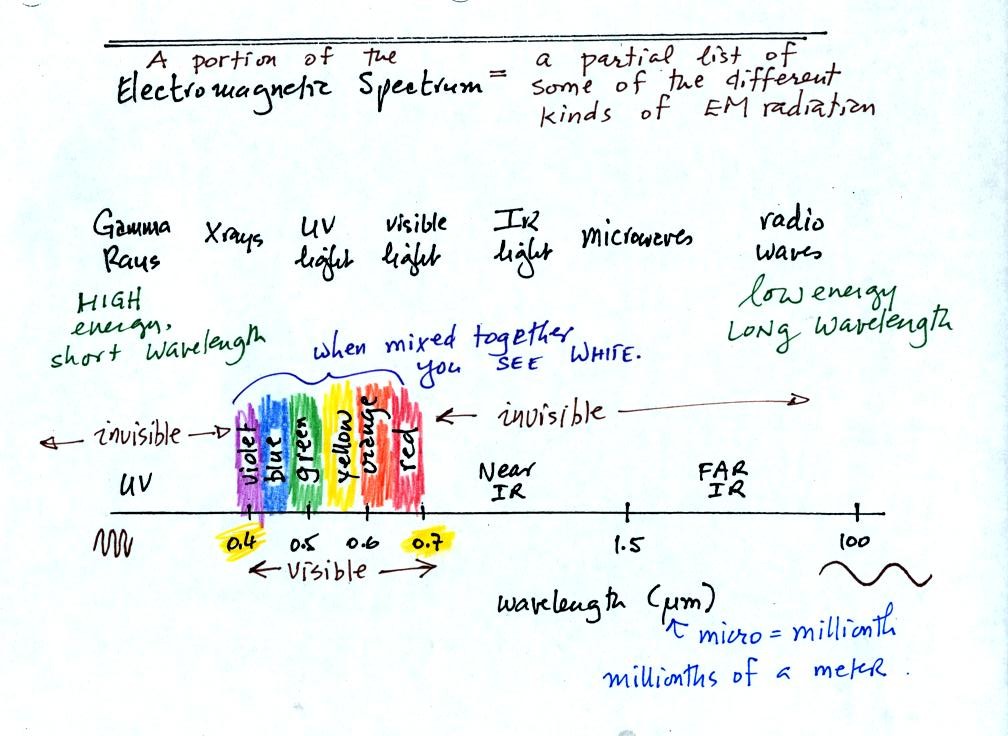

This is really just a partial

list of some of the different

types of EM

radiation. In the top list, shortwave length and high energy

forms of EM radiation are on the left (gamma rays and X-rays for

example). Microwaves and radiowaves are longer wavelength, lower

energy forms of EM radiation.

This is really just a partial

list of some of the different

types of EM

radiation. In the top list, shortwave length and high energy

forms of EM radiation are on the left (gamma rays and X-rays for

example). Microwaves and radiowaves are longer wavelength, lower

energy forms of EM radiation.

We will mostly be concerned with just ultraviolet light (UV), visible

light (VIS), and infrared light (IR). Note the micrometer

(millionths of a meter) units used for wavelength. The visible

portion of the spectrum falls between 0.4 and 0.7 micrometers (UV and

IR light are both invisible). All of the vivid colors shown above

are just EM radiation with slightly different wavelengths. WHen

you see all of these colors mixed together, you see white light.

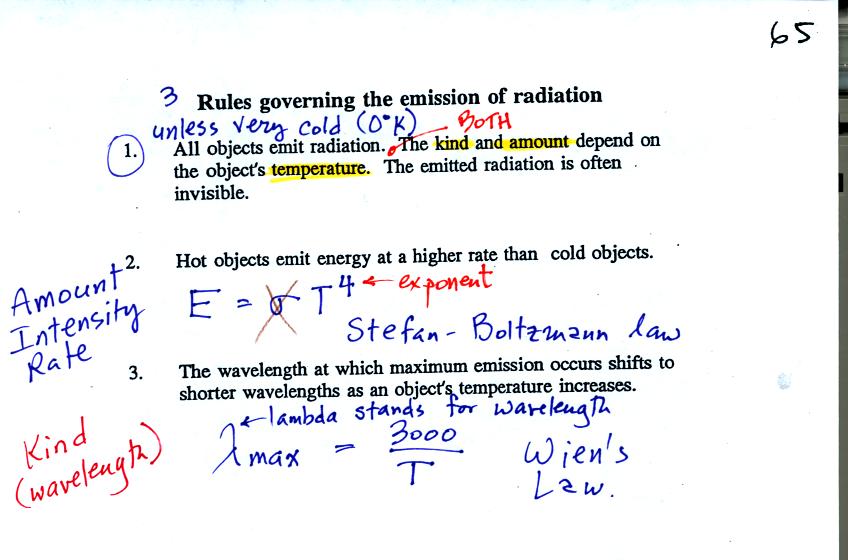

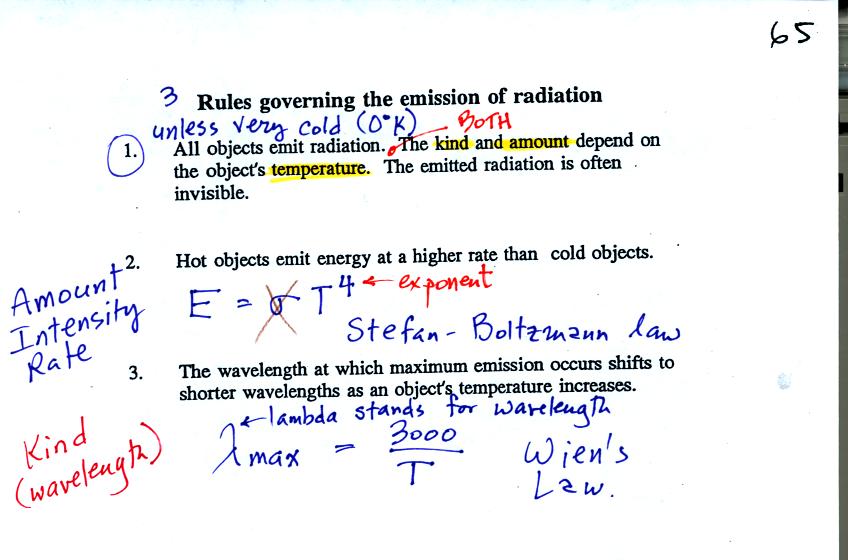

1.

Unless an object is very cold (0

K) it will emit EM

radiation. All the people, the furniture, the walls and the floor

in the classroom are emitting EM radiation. Often this radiation

will be invisible so that we can't see it and weak enough that we can't

feel it. Both the amount and kind (wavelength) of the emitted

radiation depend on the object's temperature.

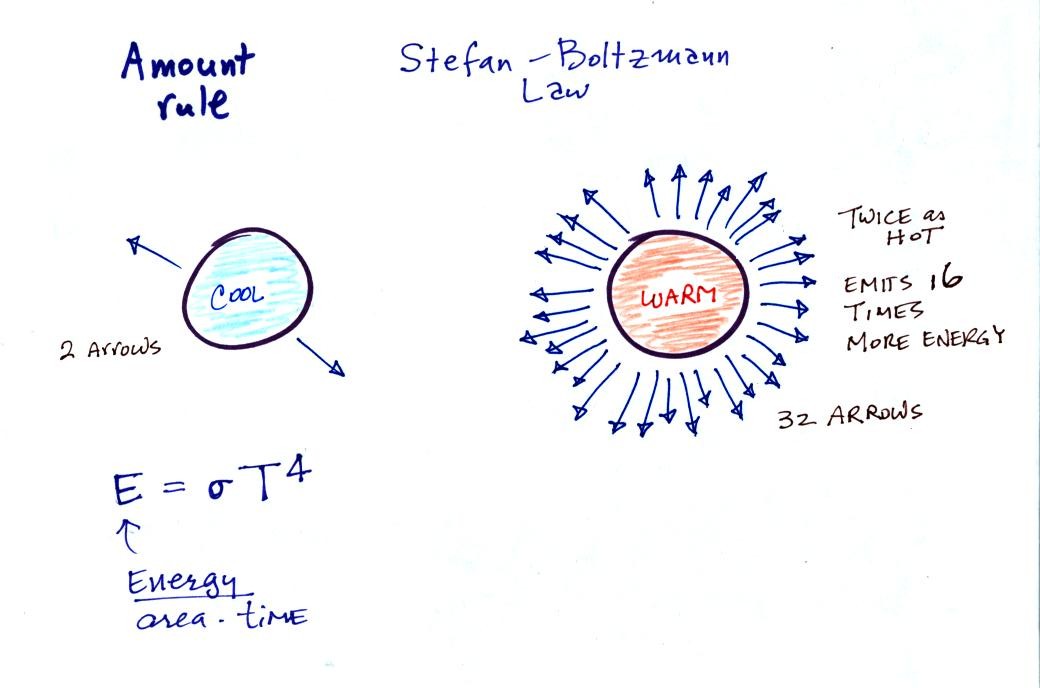

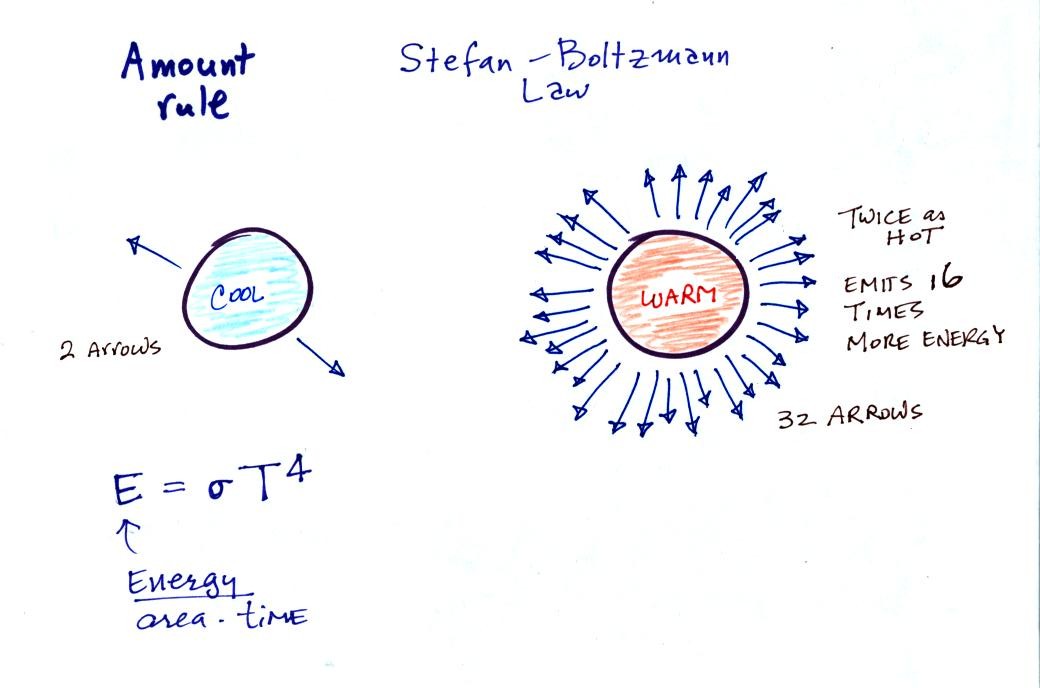

2.

The second rule allows you to

determine the amount of EM radiation (radiant energy) an object will

emit. Don't worry about the units,

you can think of this as amount, or rate, or intensity.

Don't worry about σ either, it is just a

constant. The amount depends on temperature to

the fourth

power. If the temperature of an object doubles the amount of

energy emitted will increase by a factor of 2 to the 4th power

(that's 2 x 2 x 2 x 2 = 16). A hot object just doesn't emit a

little more energy than a

cold object it emits a lot more energy than a cold object. This

is illustrated in the following figure:

3.

The third rule tells you something

about the kind of radiation emitted

by an object. We will see that objects usually emit radiation at

many different wavelengths. There is one wavelength however at

which the object emits more energy than at any other wavelength.

This is called lambda max (lambda is the greek character used to

represent wavelength) and is called the wavelength of maximum

emission. The third rule allows

you to calculate "lambda max." This is illustrated below:

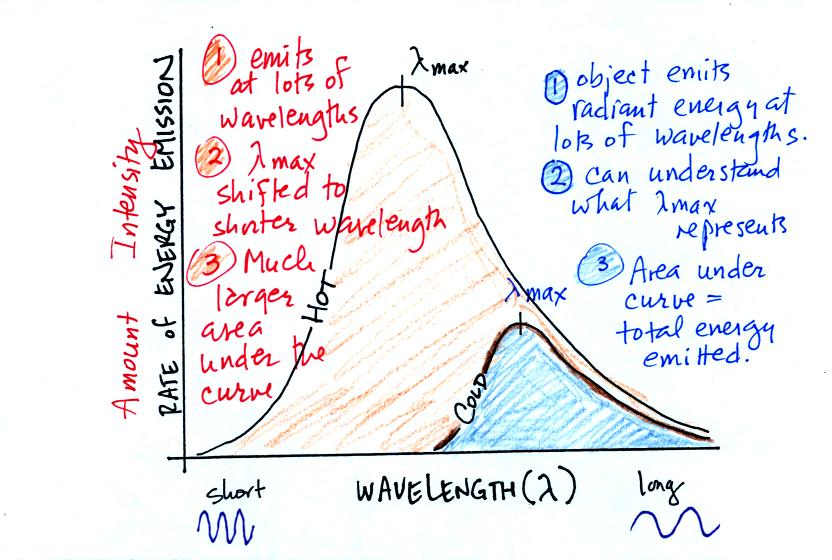

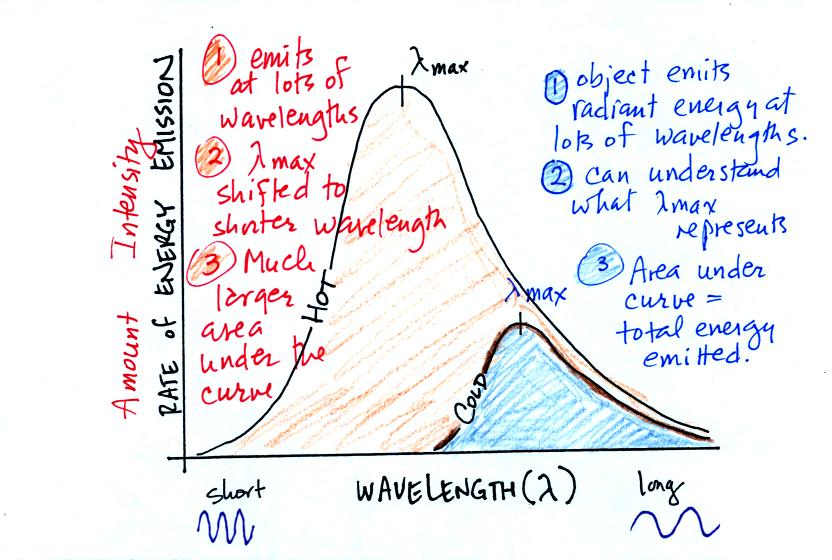

The

following graphs (at the bottom of p. 65 in the photocopied Class

Notes) also help to

illustrate the Stefan-Boltzmann law

and Wien's law.

Notice first that both and warm and the cold objects emit radiation

over a range of wavelengths.

The area under the warm object curve is much bigger than the area under

the cold object curve. The area under the curve is a measure of

the total radiant energy emitted by the object. This illustrates

the fact that the warmer object emits a lot more radiant energy than

the colder object.

Lambda max has shifted toward shorter wavelengths for the warmer

object. This is Wien's law in action. The warmer object is

emitting a lot of short wavelength radiation that the colder object

doesn't emit.

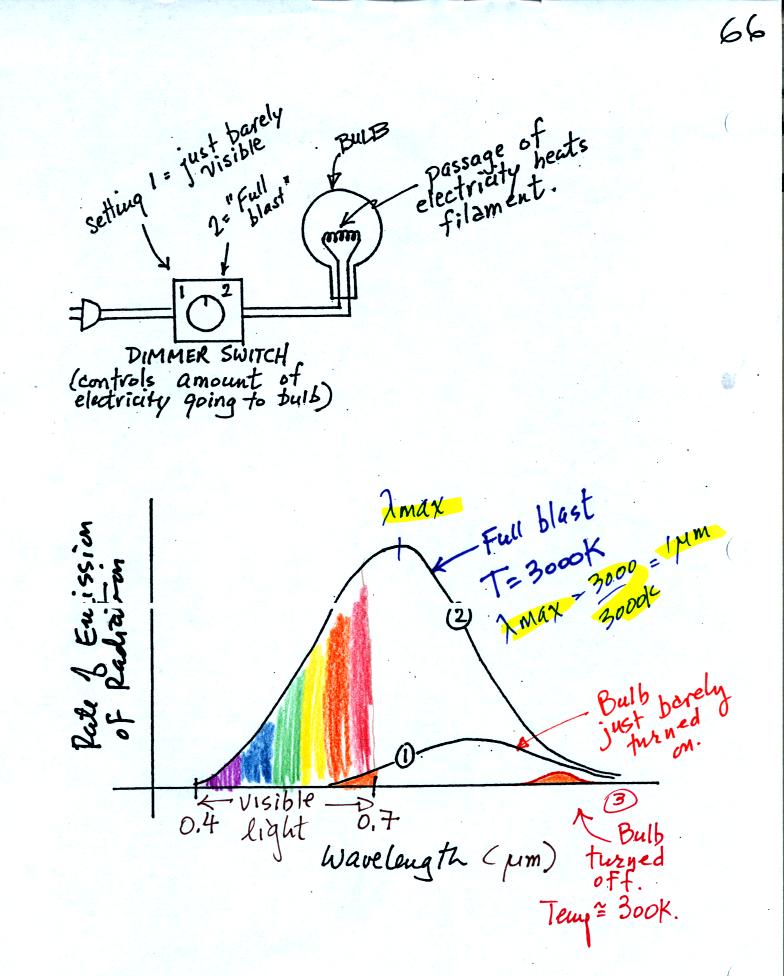

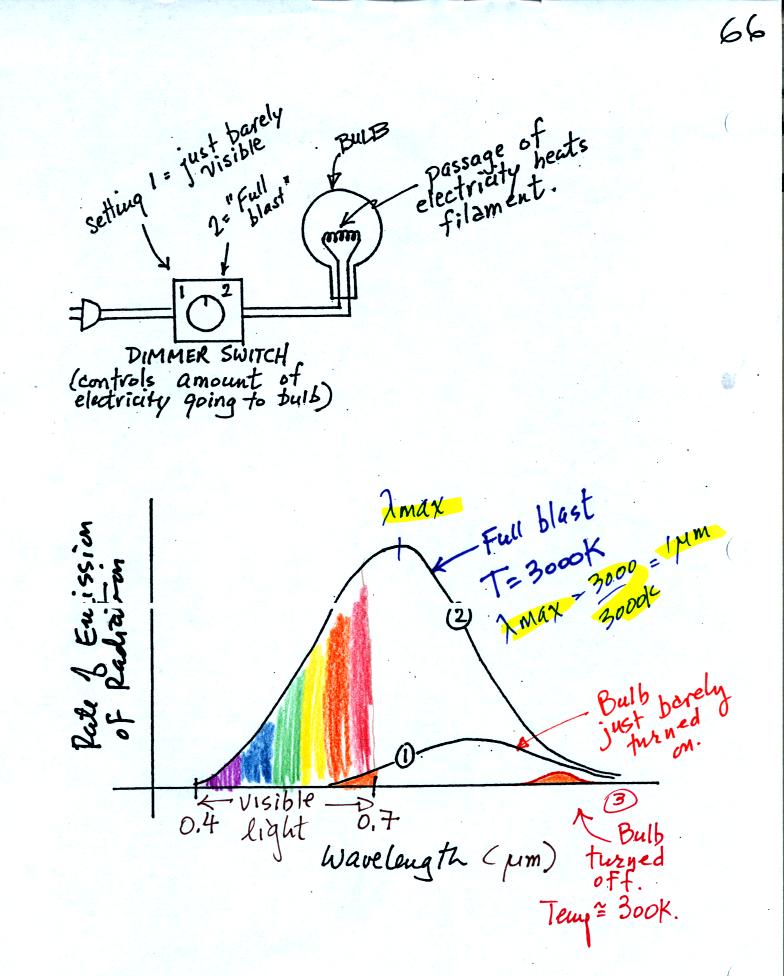

A bulb connected

to a dimmer switch can be used to demonstrate the

rules above. We'll be interested in and looking at the EM

radiation emitted by

the tungsten filament in the bulb.

We start with the bulb turned off (Point 3 near the bottom right part

of the figure above). The

filament will be at room temperature which we will assume is around 300

K (remember that is a reasonable and easy to remember value for the

average temperature of the earth's surface). The bulb will be

emitting radiation. The radiation is very weak so we

can't

feel it. It is also long wavelength far IR radiation so we

can't see it. The wavelength of peak emission is 10 micrometers.

Next we use the dimmer switch to just barely turn the bulb on (the

temperature of the filament is now about 900 K).

The bulb wasn't very bright at all and had an orange color. This

is curve 1 in the figure. Note the far left end of the curve has

moved left of the 0.7 micrometer mark - into the visible portion of the

spectrum. That is what you are able to see the small fraction of

the radiation emitted by the bulb that is visible light (but just

long wavelength red and orange light). Most of the radiation

emitted by the bulb is to the right of the 0.7 micrometer mark and is

invisible IR radiation (it is strong enough now that you could feel it

if you put your hand next to the bulb).

Finally we turn on the bulb completely. The filament temperature

is now about 3000K. The bulb is emitting a lot more visible

light, all the colors, though not all in equal amounts. The bulb

was also much brighter (a 200 Watt bulb was used so it was pretty

bright). The mixture of the colors produces a warm

white light. It is warm because it is a mixture that contains a

lot more red, orange, and yellow than blue, green, and violet

light.

Small diffraction gratings were handed out in class. A

diffraction grating will spread out all of the colors in the white

light emitted by the bulb. You could see the vivid violets, blue,

green, yellow, orange, and red light that make up white light.

It is interesting that most of the radiation emitted by

the bulb is still in the IR portion of the spectrum (lambda max is 1

micrometer). This is

something I forgot to mention in class. This is

invisible light. A tungsten bulb like this is not especially

efficient, at least not as a source of visible light.

The sun

emits electromagnetic radiation. That shouldn't come as a surprise

since you can see it and feel it. The earth also emits

electromagnetic radiation. It is much weaker and invisible.

The kind and amount of EM radiation emitted by the earth and sun depend

on their respective temperatures.

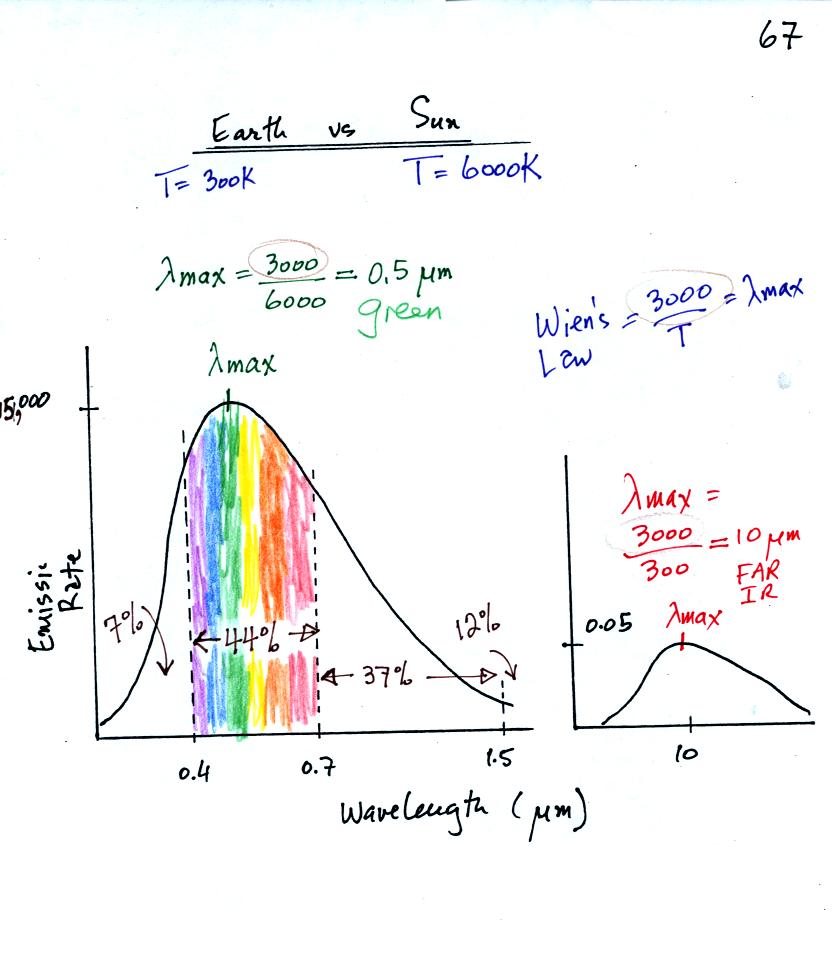

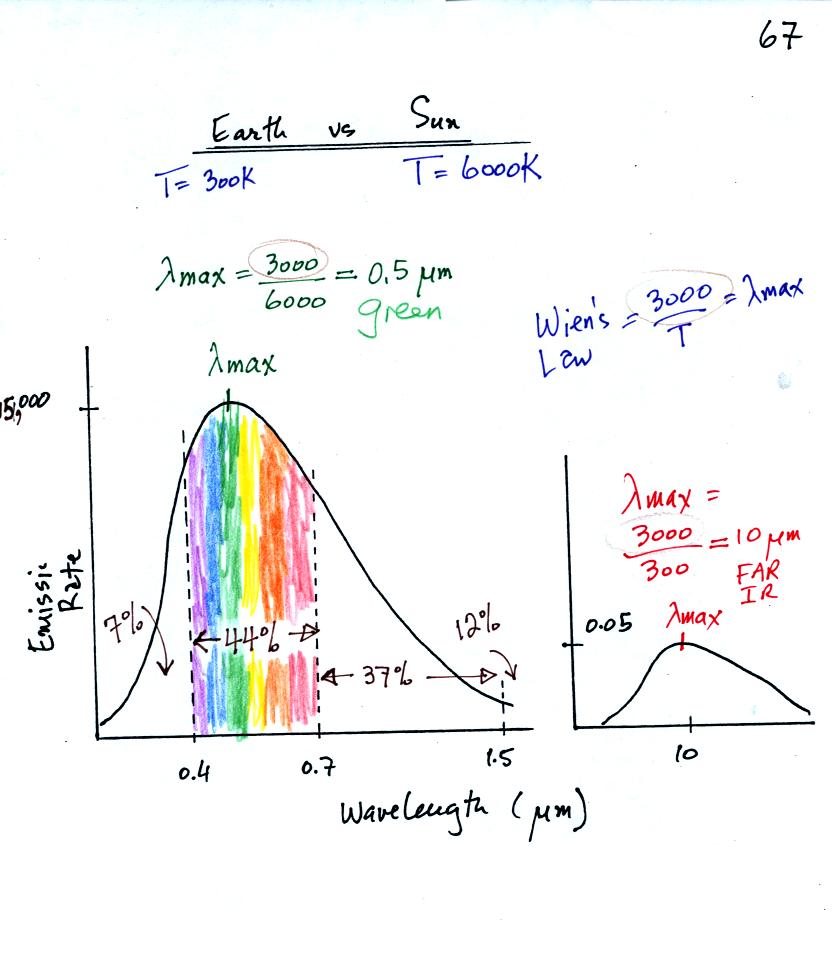

The curve on the left is for the sun. We first used

Wien's

law and a temperature of 6000 K to calculate lambda max and got

0.5 micrometers. This is green light; the sun emits more green

light than any other kind of

light. The sun doesn't appear green because it is also emitting

lesser amounts of violet, blue, yellow, orange, and red - together this

mix of

colors appears white. 44% of the radiation emitted by the sun is

visible light, 49% is IR light (37% near IR + 12% far IR), and 7%

is ultraviolet light. More than half of the light emitted by the

sun is invisible.

100% of the light emitted by the earth (temperature = 300 K) is

invisible IR light. The

wavelength of peak emission for the earth is 10 micrometers.

Because the sun (surface of the

sun) is 20 times hotter than the earth a square foot of the sun's

surface emits energy at a rate that is 160,000 times higher than a

square foot on the

earth. Note

the vertical scale on the earth curve is different than on the sun

graph. If both the earth and sun were plotted with the same

vertical scale, the earth curve would be too small to be seen.

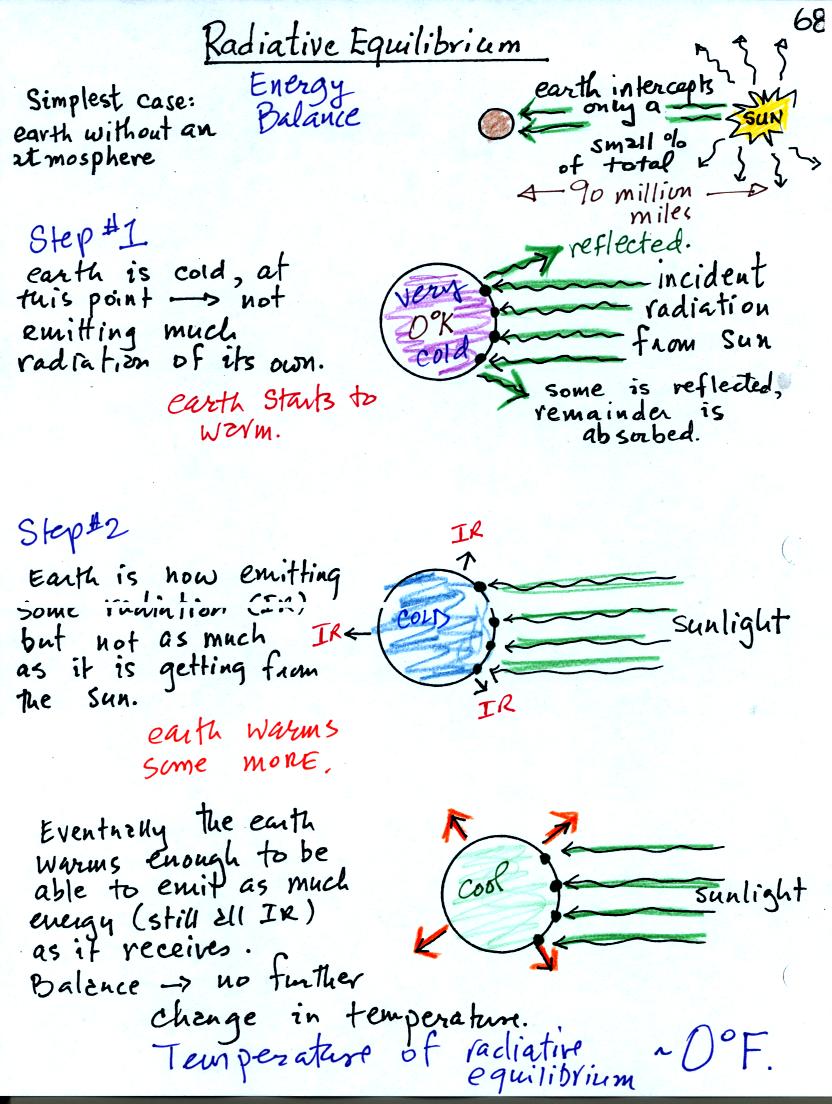

We now

have most of the tools we will need to begin to study energy balance on

the earth. It will be a balance between incoming sunlight

energy and outgoing energy emitted by the earth. We will look at

the simplest case, first, the earth without an atmosphere (or at least

an atmosphere without greenhouse gases)

You might first wonder how, with the sun emitting so much more

energy than the earth, it is possible for the earth to be in energy

balance with the sun (without the earth getting really hot like the

sun). The earth is located about 90 million miles

from the sun and therefore only absorbs a very small fraction of the

energy emitted by the sun.

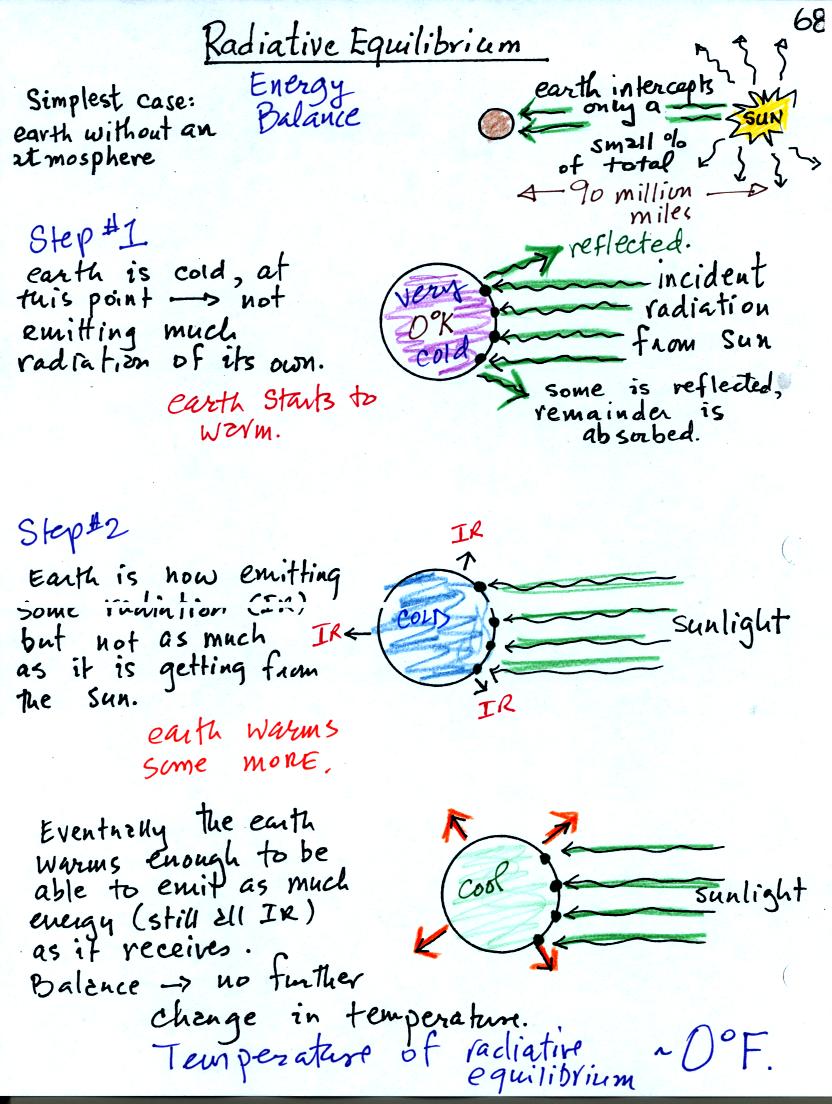

To understand how energy balance occurs we start, in Step #1, by

imagining that the earth starts out very cold and is

not emitting

any EM radiation at all. It is absorbing sunlight however so it

will

begin to warm.

Once the earth starts to warm it will also begin to emit EM

radiation, though not as much as it is getting from the sun (the

slightly warmer earth in the middle picture is now colored blue).

Because the earth is still gaining more energy than it is losing the

earth will warm some more.

Eventually it will warm enough that the earth (now shaded green) will

emit the same amount

of energy (though not the same wavelength energy) as it absorbs from

the sun. This is radiative equilibrium, energy balance. The

temperature at

which this occurs is 0 F.

That is called the temperature of radiative equilibrium. You

might remember this is the figure for global annual average surface

temperature on the earth without the greenhouse effect.

Next we

are going to see that the atmosphere behaves somewhat differently, when

it comes to emitting and absorbing electromagnetic radiation, than the

earth or the sun. We will need to understand, in particular, how

the atmosphere filters incoming sunlight and outgoing IR radiation

emitted by the ground. Then we will be able to study energy

balance on the earth with an atmosphere (and one that contains

greenhouse gases).

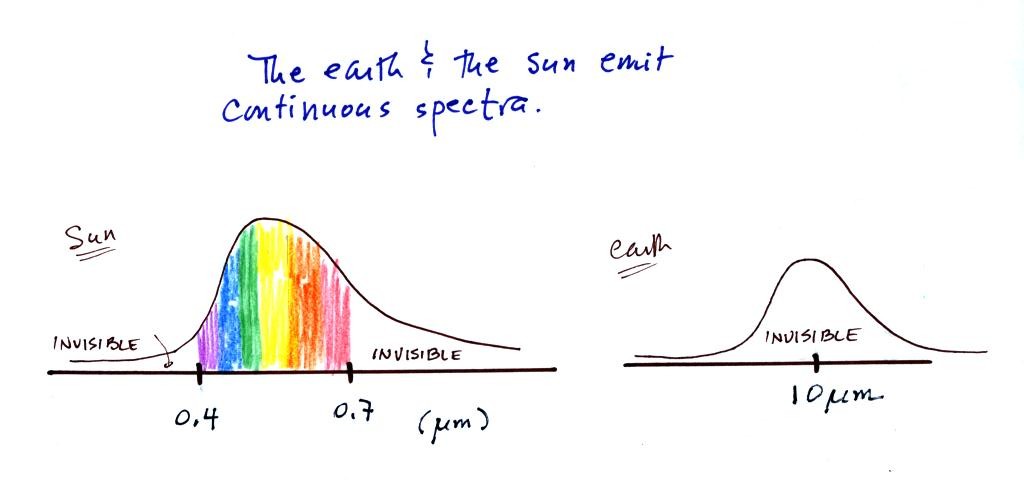

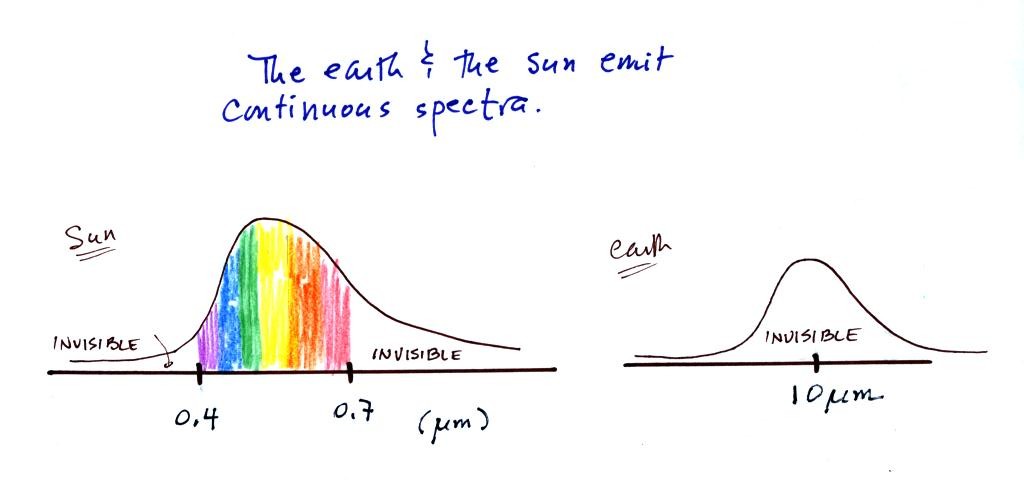

In some respects the earth and the sun behave just like the

tungsten filament in the light bulb used in the class

demonstration. Both the earth and the sun emit continuous

spectra. Part of the light emitted by the sun falls in the

visible part of the spectrum. If you were to look at the sun

(something you shouldn't do of course) with one of the diffraction

gratings handed out in class you would see all the colors of visible

light. There wouldn't be any gaps or colors missing. This

is shown again at the top of the figure below.

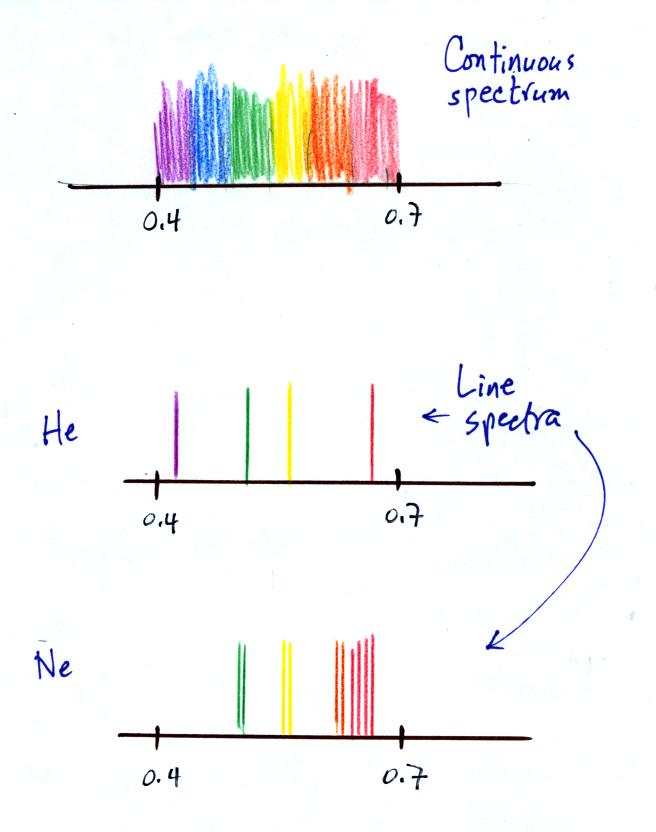

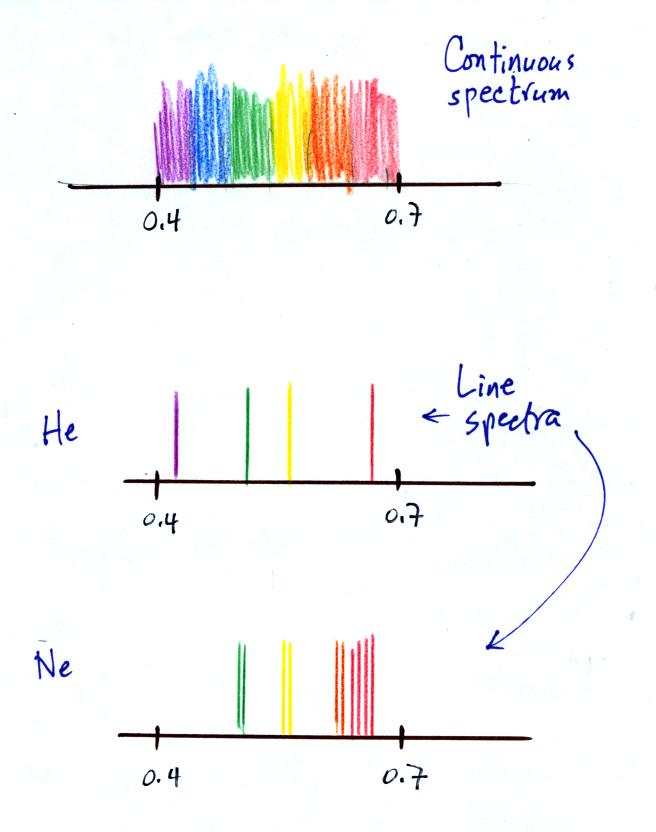

Gases behave differently. We looked at the visible light

emitted by helium (a high-voltage power supply was need to heat the

helium so that it would be hot enough to emit visible light).

Rather than a continuous spectrum, the helium emitted only certain

wavelengths. This is called a line spectrum. Helium

contains only two electrons and is a relatively simple atom and its

line spectrum was also fairly simple.

Neon (Ne) also emitted a line spectrum, thought there were more lines

at different wavelengths.

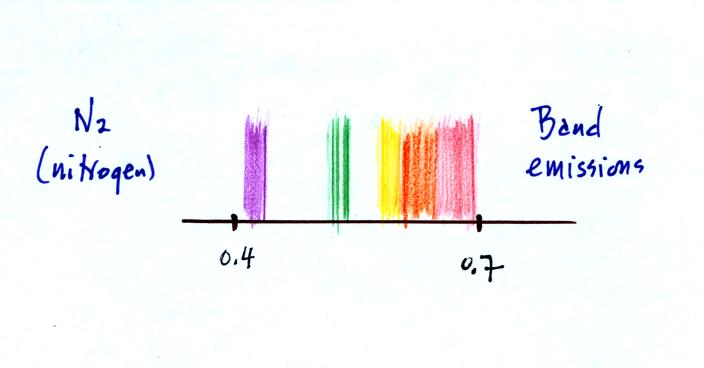

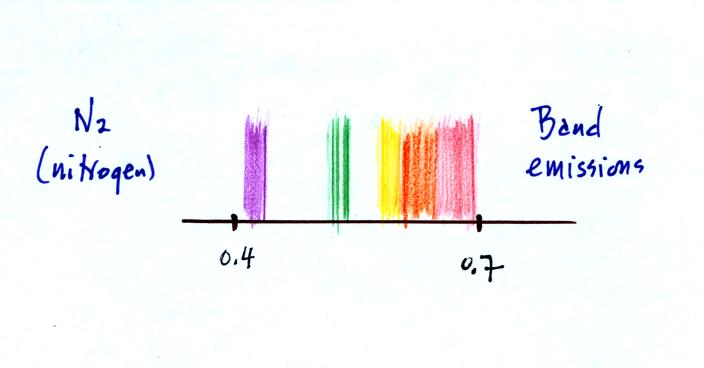

Finally we looked at the visible light emitted by molecular

nitrogen. In this case the spectrum was somewhere in between a

continous spectrum and a line spectrum. You were able to see

bands of colored light rather than clear line emitted by the nitrogen

(the bands are probably very closely spaced lines).

This is closer to being a continous spectrum but there were still

gaps, wavelengths without any emissions.

In the

same kind of way, air absorbs some wavelengths and transmits

others. We will need to worry about the filtering effect of the

atmosphere on ultraviolet, visible, and infrared light because all

three types of light are found in sunlight.

This is really just a partial

list of some of the different

types of EM

radiation. In the top list, shortwave length and high energy

forms of EM radiation are on the left (gamma rays and X-rays for

example). Microwaves and radiowaves are longer wavelength, lower

energy forms of EM radiation.

This is really just a partial

list of some of the different

types of EM

radiation. In the top list, shortwave length and high energy

forms of EM radiation are on the left (gamma rays and X-rays for

example). Microwaves and radiowaves are longer wavelength, lower

energy forms of EM radiation.