Thursday Oct. 22, 2009

click here to download today's notes

in a more printer friendly format.

Some zydeco music from the Best of Beausoleil CD before class this

morning.

The Experiment #2 reports have been graded

and were returned in class today. You are allowed to revise your

report; revisions are due on or before Thu., Nov. 5. Please

return your original report with your revised report.

The Experiment #4 materials were

distributed in class today. Experiment #4 reports are due on

Tue., Nov. 10.

A new Humidity

Optional Assignment was distributed in class. The assignment

is due next Thursday, Oct. 29. There was also an In-class

Optional Assignment today. You'll find the questions below

embedded in the online notes. You may turn in answers to the

questions if you wish at the start of class next Tuesday.

We'll work

through 4 humidity example problems today.

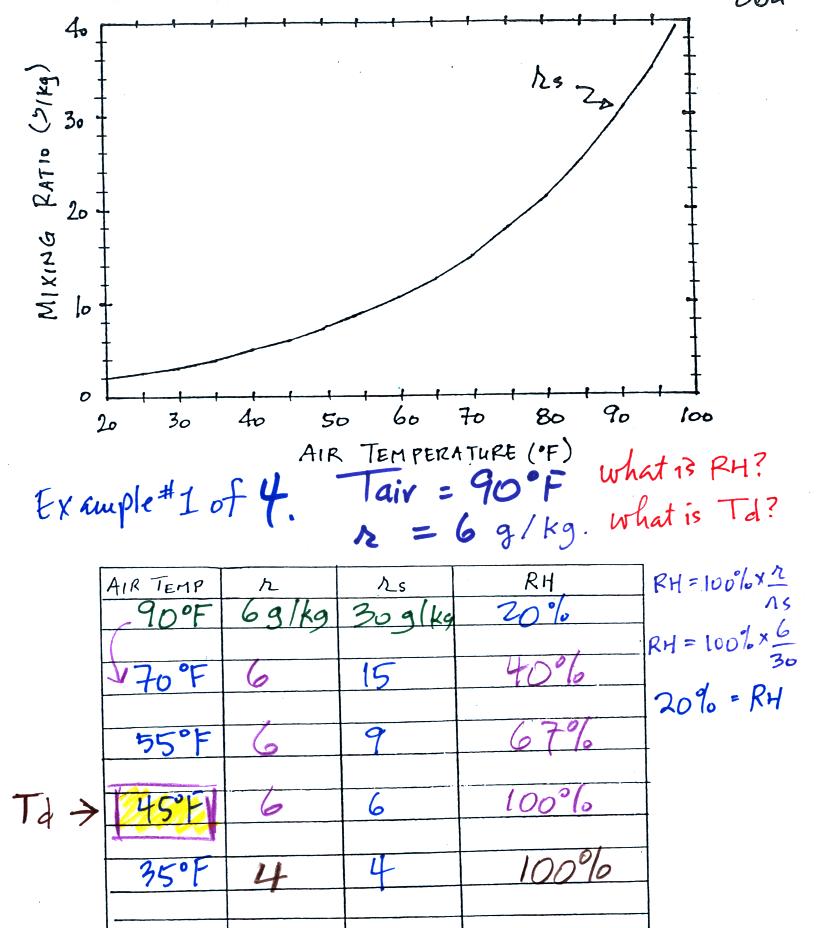

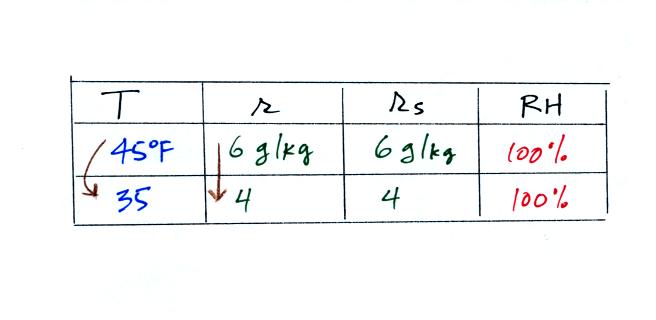

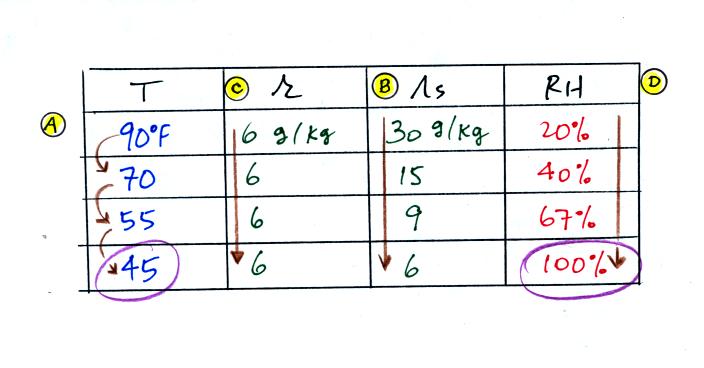

Example 1

We were given an air temperature of 90 F and a mixing ratio (r) of 6 g/kg.

We're supposed to find the relative humidity (RH) and

the dew point temperature (Td). You might have a hard

time

understanding this if

you're seeing it for

the first

time. The series of steps that we followed are retraced

below:

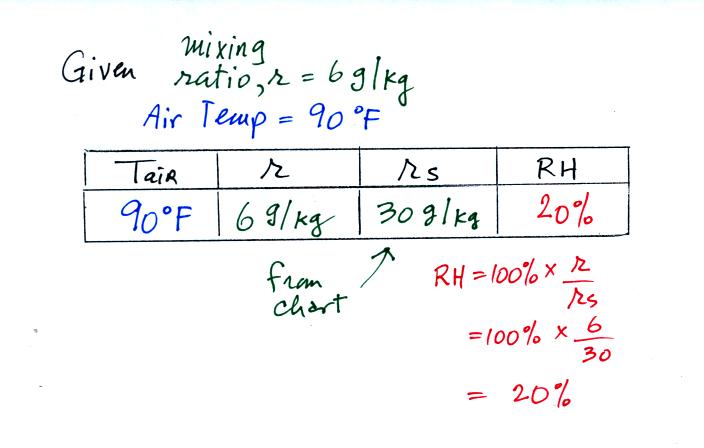

We start by entering the data we were given in the

table. Once

you know the air's temperature you can look up the saturation mixing

ratio value; it is 30 g/kg for 90 F air. 90 F air could

potentially hold 30 grams of water vapor per kilogram of dry air (it

actually contains 6 grams per kilogram in this example). A table

of

saturation mixing ratio values can be found on p. 86 in the ClassNotes.

Once you know mixing ratio and saturation mixing ratio you can

calculate the relative humidity (you divide the mixing ratio by the

saturation mixing ratio, 6/30, and multiply the result by 100%).

You ought to be able to work out the ratio 6/30 in your head (6/30 =

1/5 = 0.2). The RH is 20%.

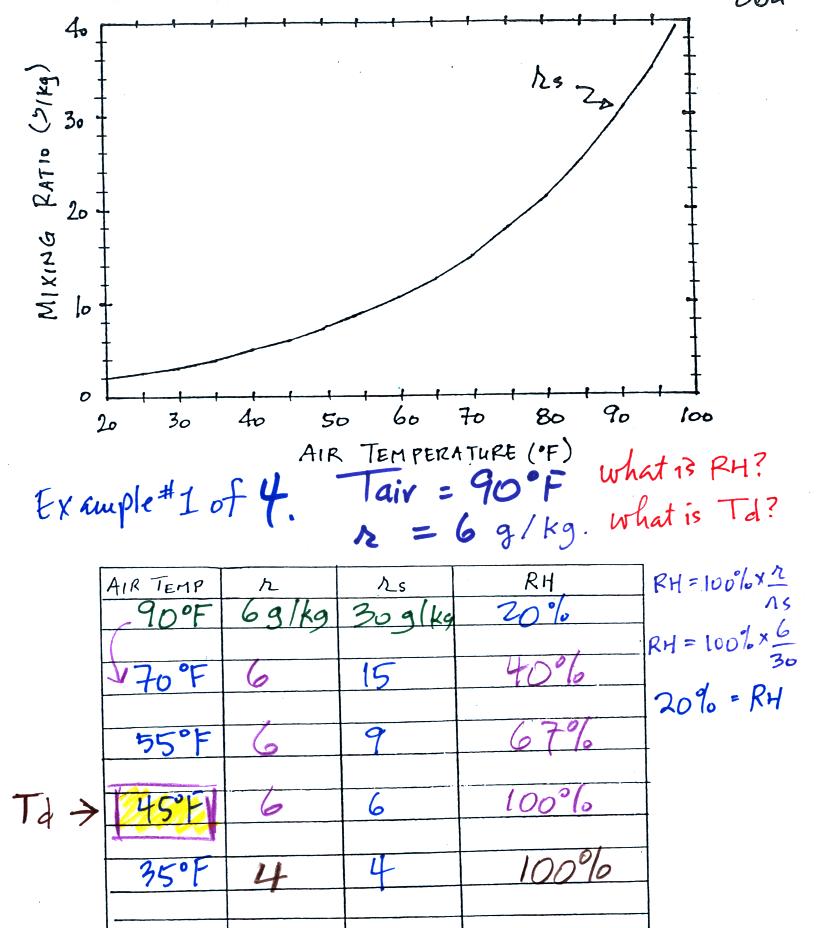

The numbers we just figured out are shown on the top line

above.

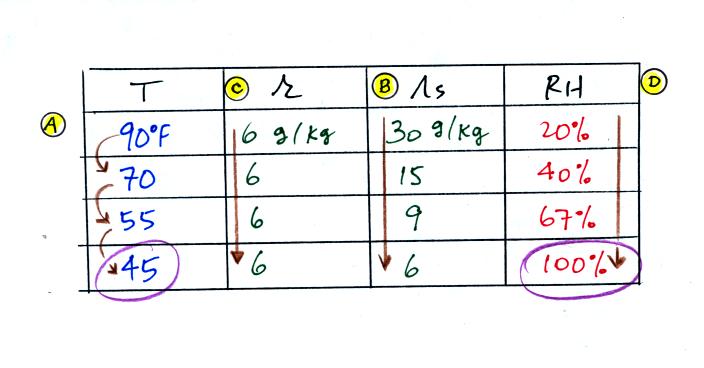

(A) We imagined cooling the air from 90F to 70F, then to 55F, and

finally to 45F. Pay attention to what is happening to the mixing

ratio, saturation mixing ratio, and relative humidity as the air cools.

(B) At each step we looked up the saturation mixing ratio and entered

it on the chart. Note that the saturation mixing ratio values

decrease as the air is

cooling.

(C) The mixing

ratio doesn't

change as we cool the air. The only

thing that changes r is adding or removing water vapor and we aren't

doing either.

(D) Note how the relative

humidity is increasing as we cool

the

air. The actual amount of water vapor in the air isn't changing,

it is just the air's capacity that is decreasing.

Finally at 45 F the RH becomes 100%. You have cooled the air

until it has become

saturated. This is a special point, this is the dew

point

temperature.

What would happen if we cooled the air

further still, below the dew

point temperature?

35 F air can't hold the 6 grams of water vapor

that 45 F air can. You can only "fit" 4 grams of water vapor into

the 35 F air. The remaining 2 grams of water vapor would condense

and form water. If

this happened at ground level the ground would get wet with dew.

If it happens above the ground, the water vapor condenses onto small

particles in the air and forms fog or a cloud. Because water

vapor is being taken out of the air (and being turned into water), the

mixing

ratio will now decrease from 6 to 4.

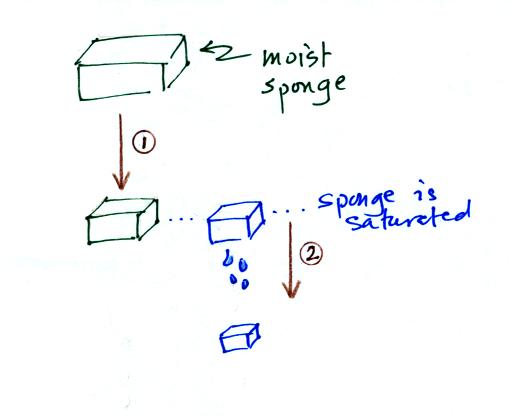

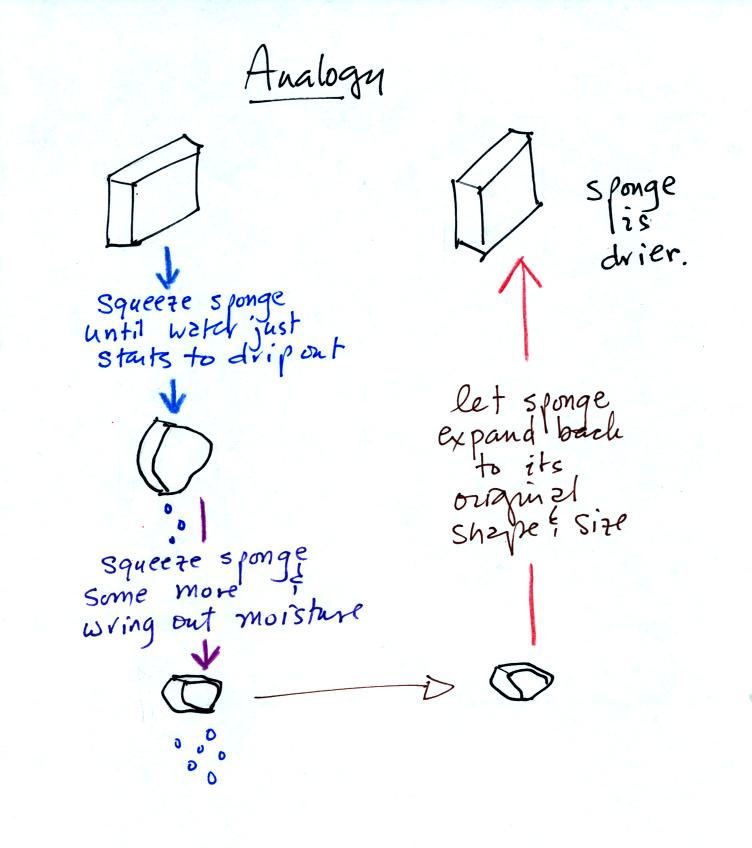

In many ways cooling moist air is liking squeezing a

moist sponge

Squeezing the

sponge and reducing its volume is like cooling moist air and reducing

the saturation mixing ratio. (1) At first when you sqeeze the

sponge

nothing happens, no water drips out. Eventually you get to a

point where the sponge is saturated. This is like reaching the

dew point. (2) If you squeeze the sponge any further (or cool air

below

the dew point) water will begin to drip out of the sponge (water vapor

will condense from the air).

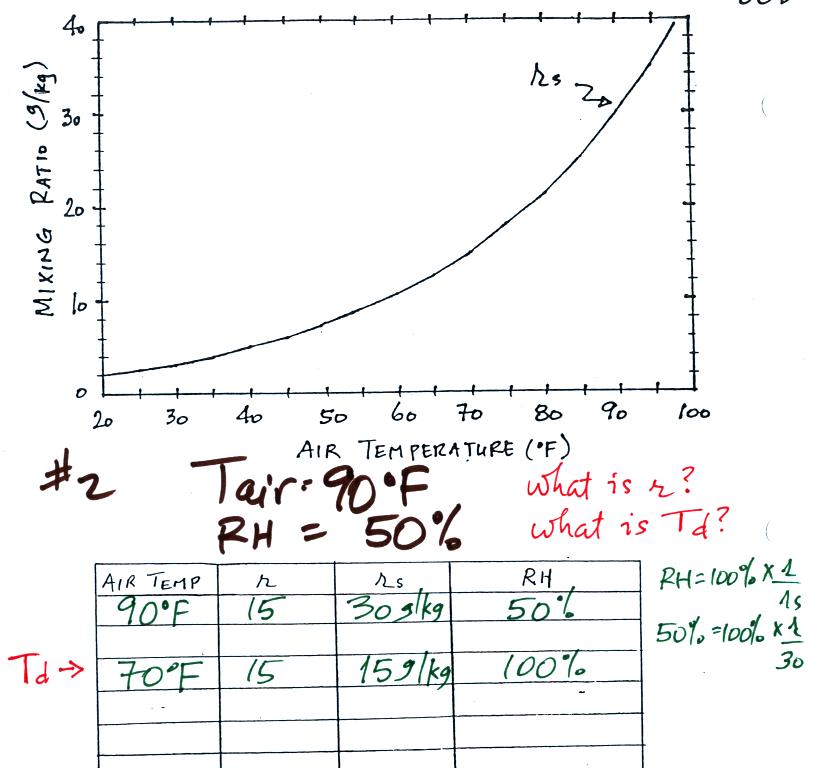

Example 2

The work that we did in class is shown above. Given an air

temperature

of 90

F and a relative humidity of 50% you are supposed to figure out the

mixing ratio (15 g/kg) and the dew point temperature (70 F). The

problem is worked out in detail below:

First you fill in the air temperature and the RH data that

you are

given.

(A) since you know the air's temperature you can look up the

saturation mixing ratio (30 g/kg).

(B) Then you might be able to figure out the mixing ratio in your

head. Air that is filled to 50% of its capacity could hold up to

30 g/kg. Half of 30 is 15, that is the mixing ratio. Or you

can substitute into

the relative humidity formula and solve for the mixing ratio.

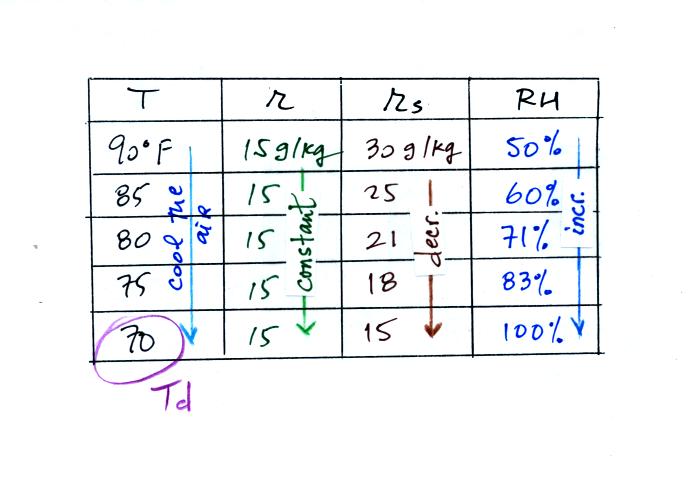

Finally you imagine cooling the air. The

saturation mixing ratio decreases, the mixing ratio stays constant,

and the relative humidity increases. In this example the RH

reached 100% when the air had cooled to 70 F. That is the dew

point temperature.

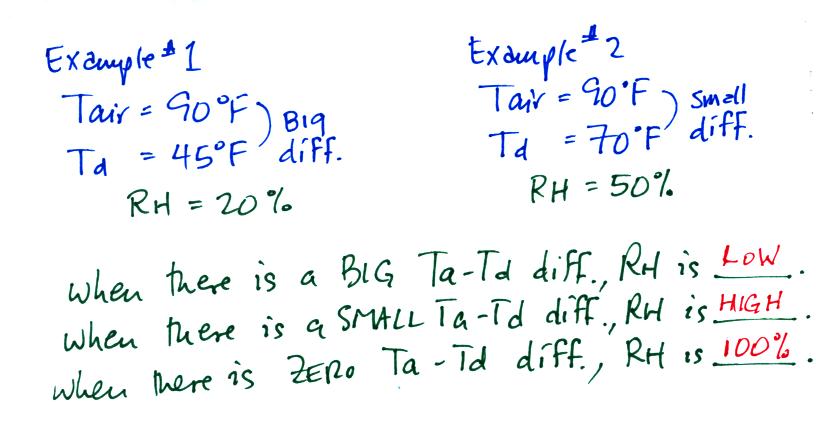

We can use

results from humidity problems #1 and #2 worked in class on Monday to

learn a useful rule.

In the first

example the difference between the air and dew point

temperatures was large (45 F) and the RH was low (20%).

In the 2nd problem the difference between the air and dew point

temperatures was

smaller (20 F) and the RH was higher (50%). The easiest way to

remember

this

rule is to remember the case where there is no difference between the

air and dew

point temperatures. The RH then would be 100%.

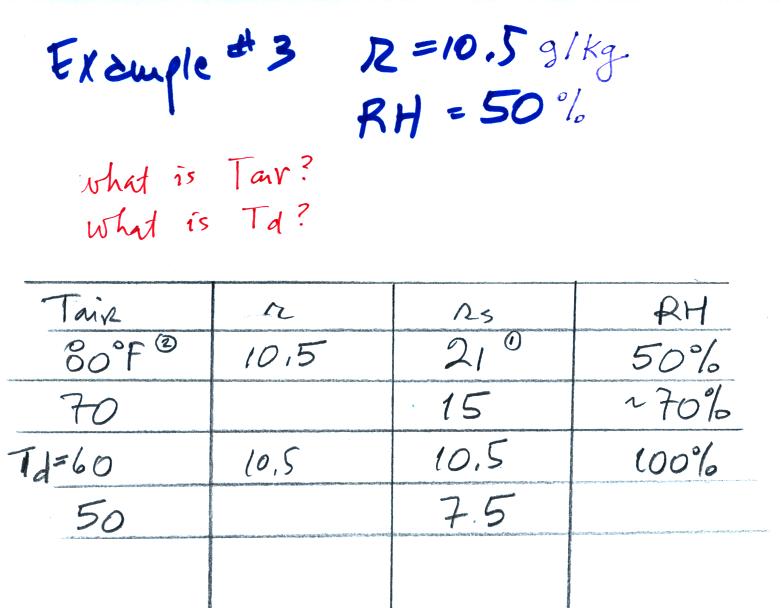

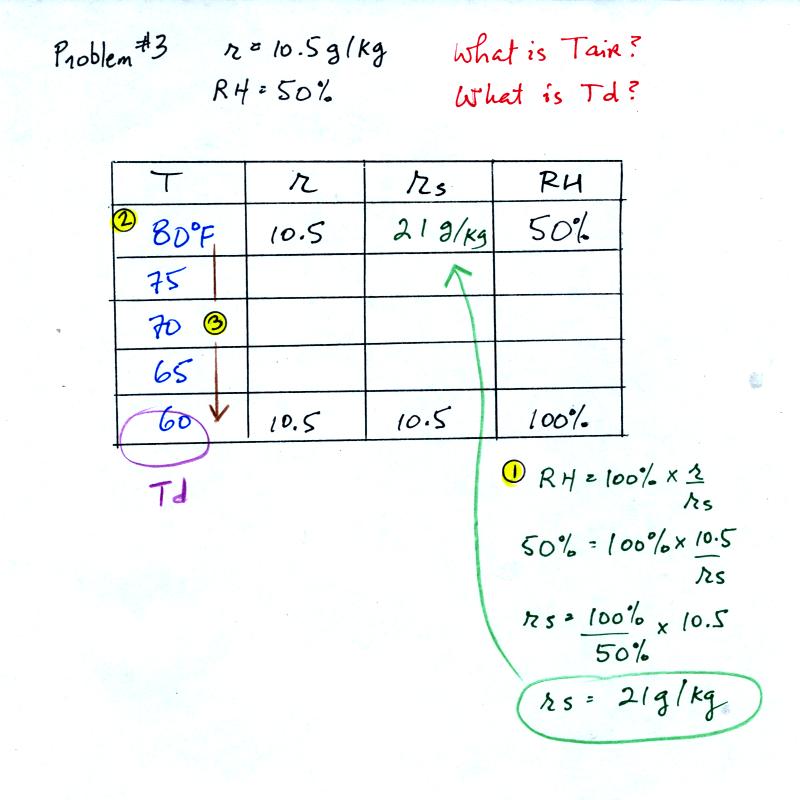

Example 3

You're given the mixing ratio (10.5) and the relative humidity

(50). What are the units (g/kg and %). Here's the play by

play solution to the question

You are given a

mixing ratio

of 10.5 g/kg and a relative humidity of 50%. You need to figure

out the air temperature and the dew point temperature.

(1) The air contains 10.5 g/kg of water vapor, this is 50%,

half, of what the air

could potentially hold. So the air's capacity, the saturation

mixing ratio must be 21 g/kg (you can either do this in your head or

use the RH equation following the steps shown).

(2) Once you know the saturation mixing

ratio you can look up the air temperature in a table (80 F air has a

saturation mixing ratio of 21)

(3) Then you

imagine cooling the air until the RH becomes 100%. This occurs at

60 F. The dew point is 60 F.

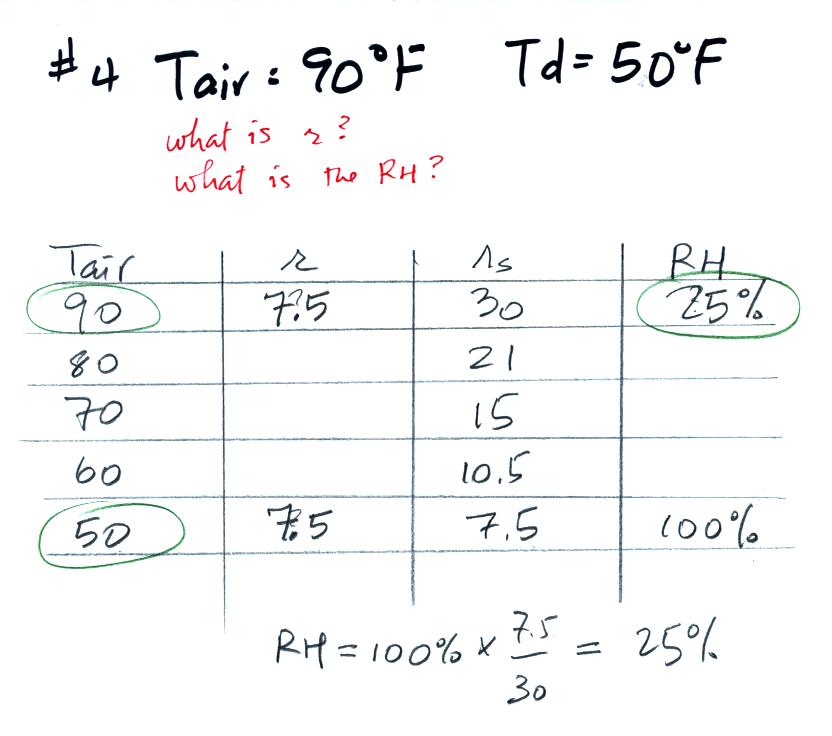

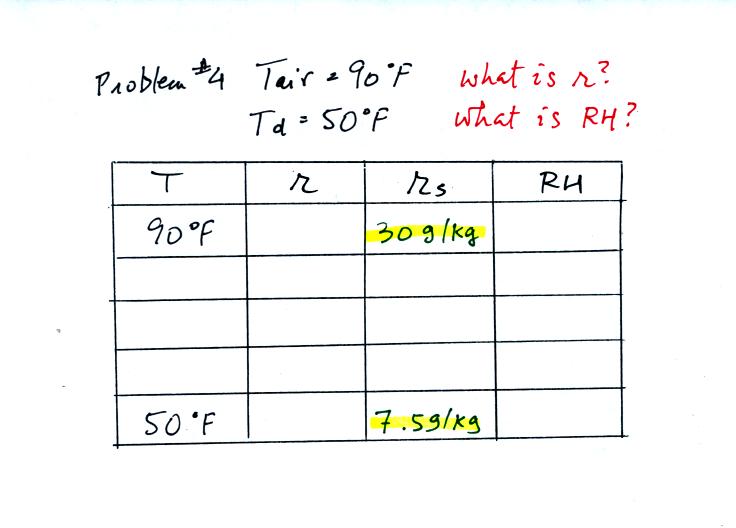

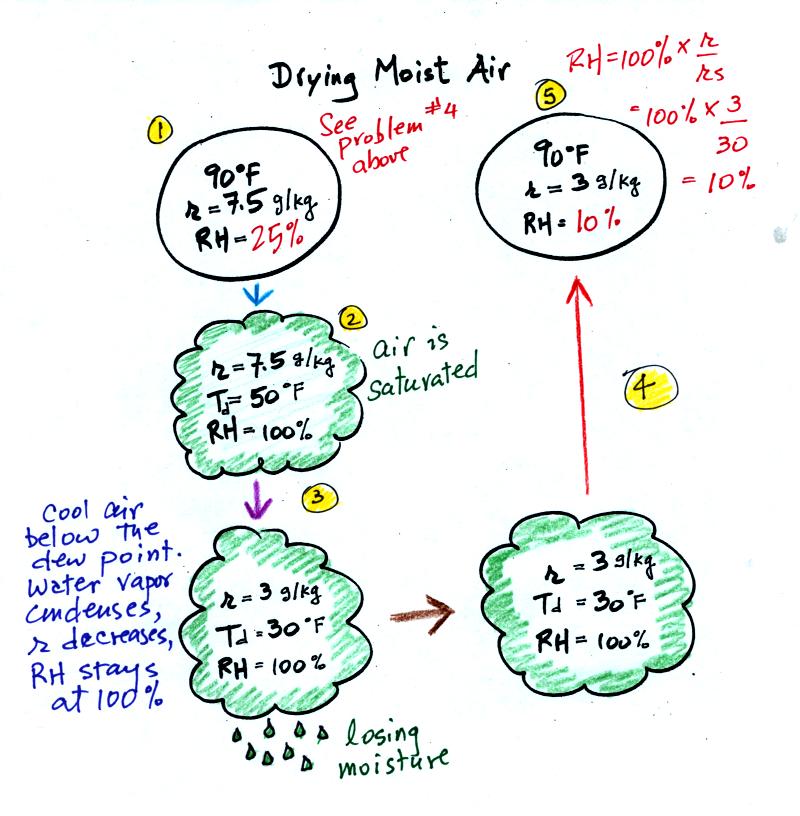

Example 4

probably the most difficult problem of the bunch.

Here's what we did in class, we

were given the air temperature and the dew point temperature. We

were supposed to figure out the mixing ratio and the relative

humidity.

We enter the two temperatures onto a chart and look up the

saturation

mixing ratio for each.

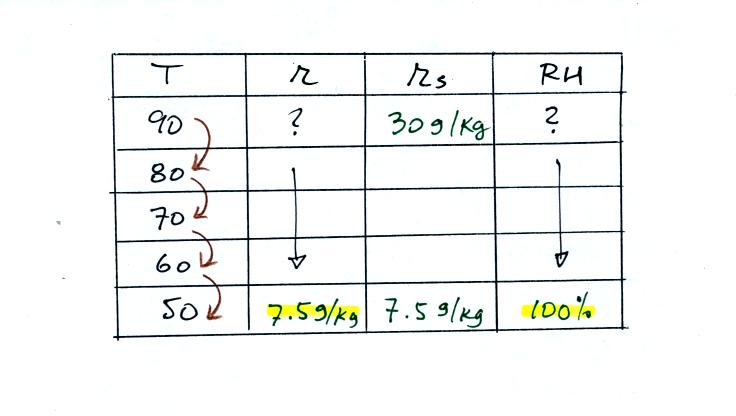

We ignore the fact that we don't know the mixing

ratio. We do know that if we cool the 90 F air to 50 F the RH

will

become

100%. We can set the mixing ratio equal to the value of the

saturation mixing ratio at 50 F, 7.5 g/kg.

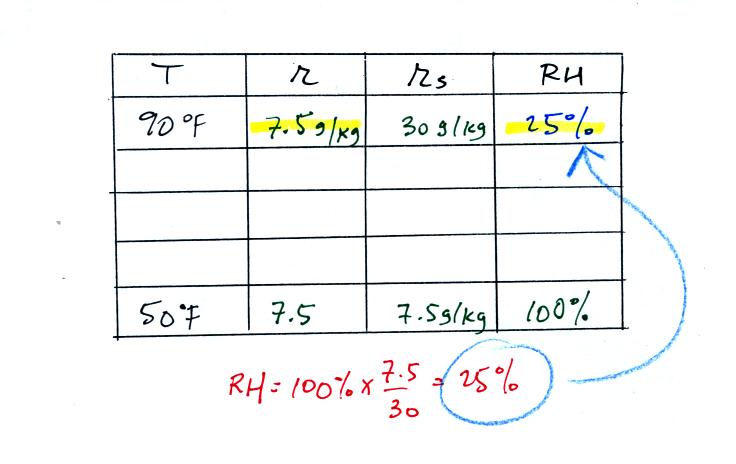

Remember back to the three earlier examples. When we

cooled air

to the the dew point, the mixing ratio didn't change. So the

mixing ratio must have been 7.5 all along. Once we know the

mixing ratio in the 90 F air it is a simple matter to calculate the

relative humidity, 25%.

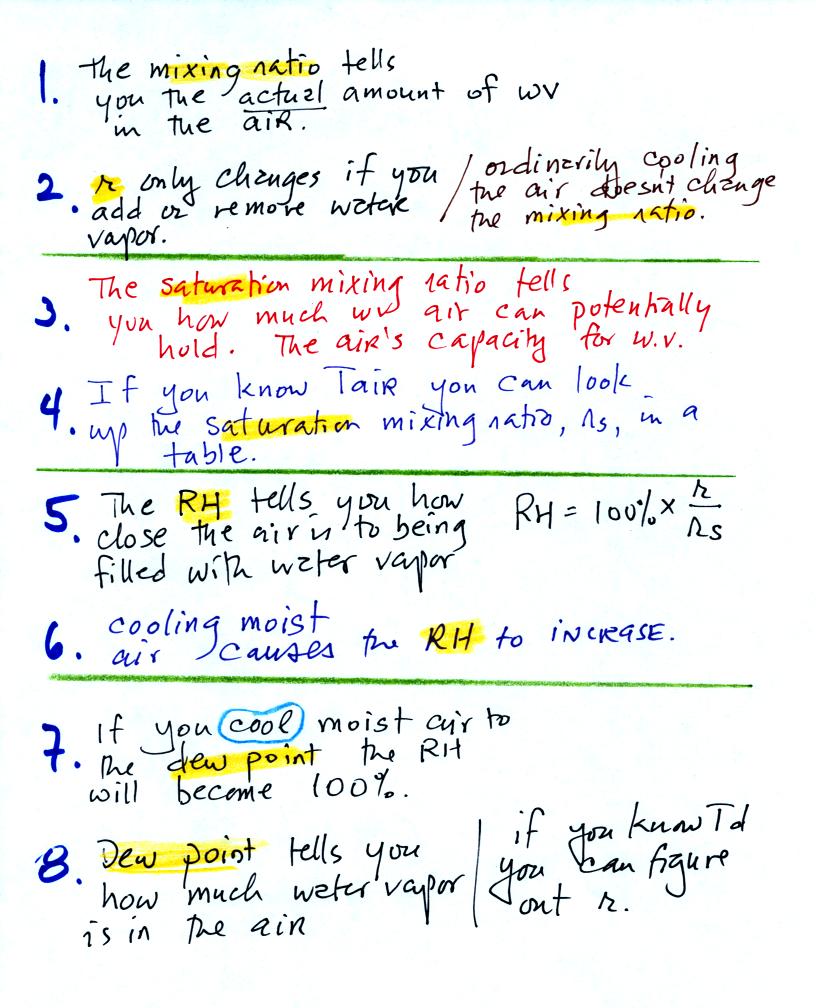

Here's a list of some of the important facts and properties of the

4 humidity variables that we have been talking about.

After working through the 4 humidity problem examples you should

be

able to answer the following questions. This is the first of two

questions that formed part of an In-class Optional

Assignment. If you weren't in class, answer this question

& Question 2 below

and turn in your work at the beginning of class on Tuesday to receive

credit.

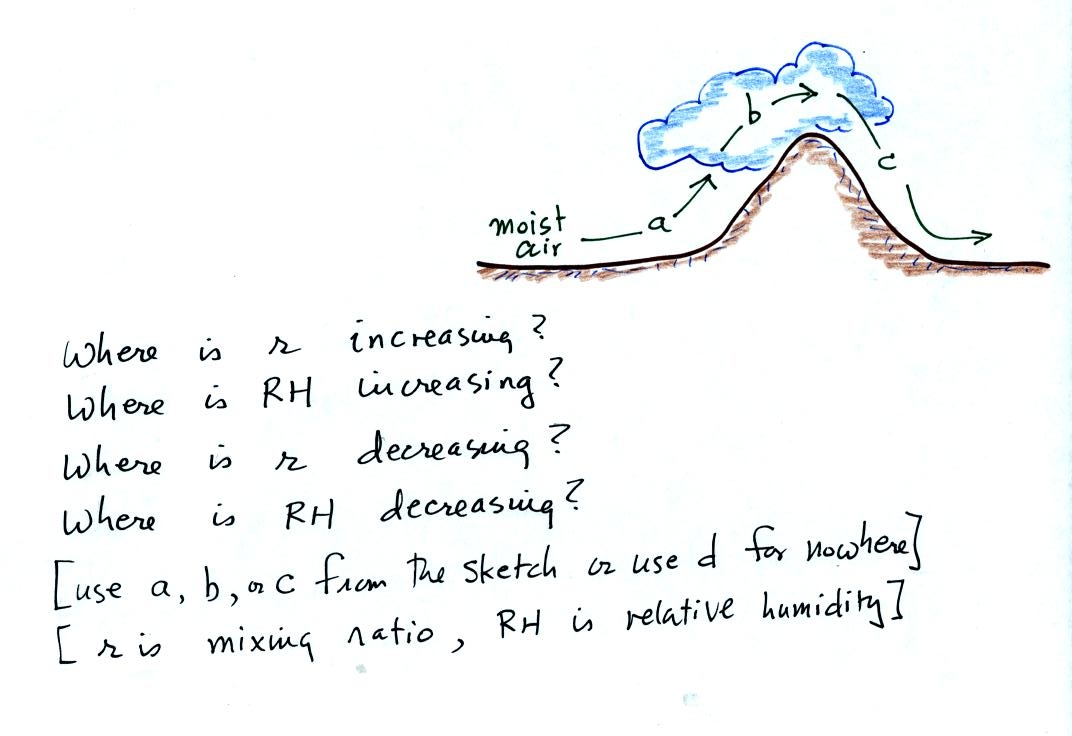

Question #1

Question #2

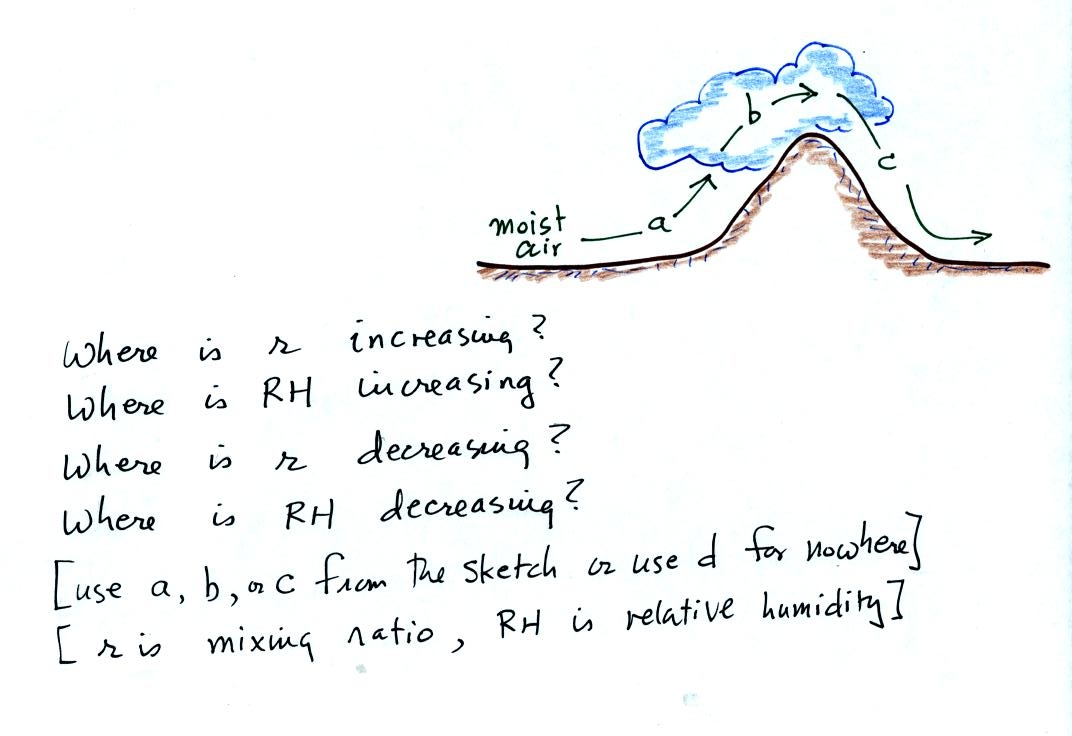

Now we can

start to use what we have learned about humidity

variables (what they tell you about the air and what causes them to

change value) to learn some new things. The figure below is on p.

87 in the photocopied ClassNotes.

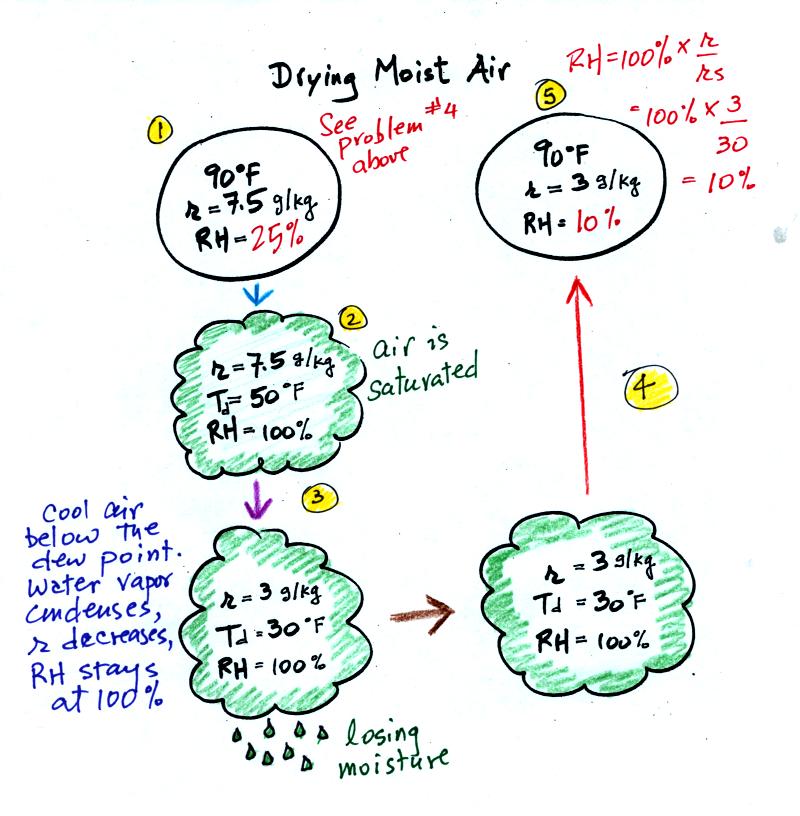

At Point 1 we start with some 90 F air with a relative

humidity of 25%, fairly dry air (these data are the same as in Problem

#4 on Monday). Point 2 shows the air being cooled to the dew

point, that is

where the relative humidity would reach 100% and a cloud would form.

Then the air is cooled below the dew

point, to

30 F. Point 3 shows the 30 F air can't hold the 7.5 g/kg of water

vapor that

was originally found in the air. The excess moisture must

condense (we will assume it falls out of the air as rain or

snow). When air reaches 30 F it contains 3 g/kg, less than half

the

moisture that it originally did (7.5 g/kg). Next, Point

4, the 30

F air is warmed back to 90 F, the starting temperature, Point 5.

The air

now

has a RH of only 10%.

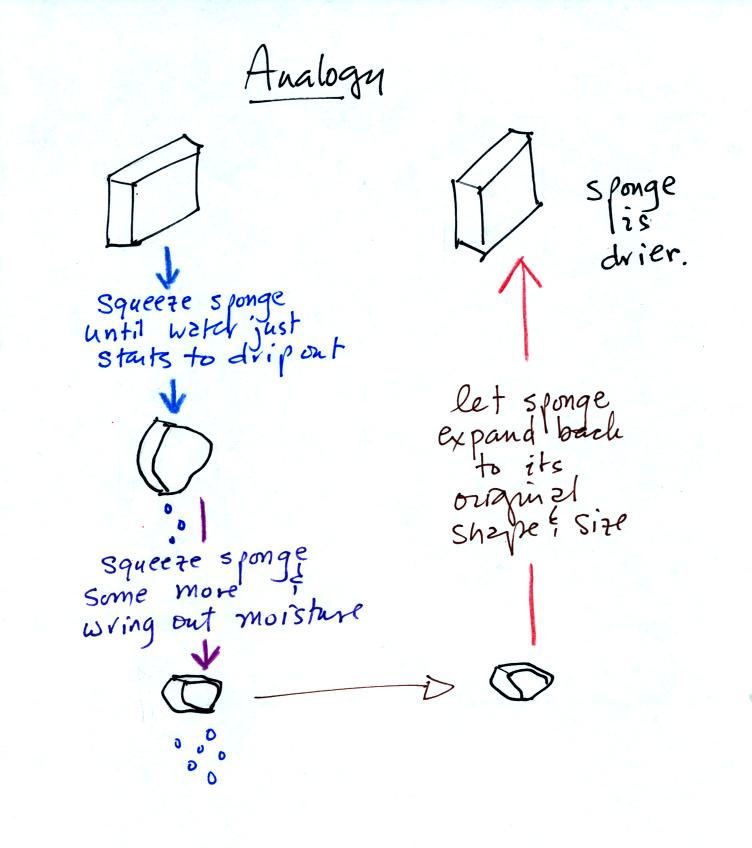

Drying moist air is like wringing moisture from a wet sponge.

You start to

squeeze the sponge and nothing happens at first (that's like cooling

the air, the mixing ratio stays constant as long as the air doesn't

lose any water vapor). Eventually water will start to drop from

the sponge (with air this is what happens when you reach the dew point

and continue to cool the air below the dew point). Then you let

go of the sponge and let it expand back

to its orignal shape and size (the air warms back to its original

temperature). The sponge (and the air) will be drier than when

you started.

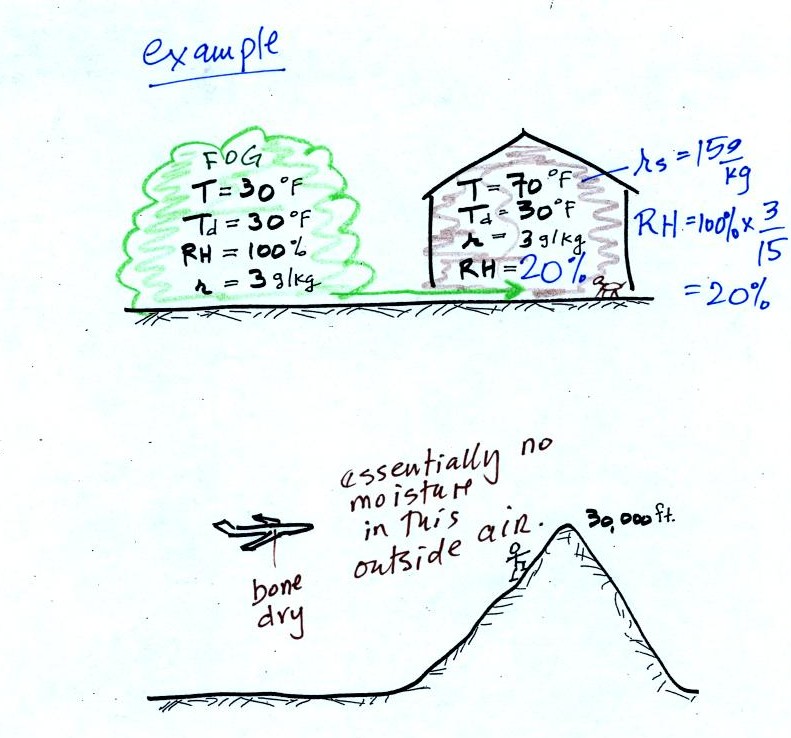

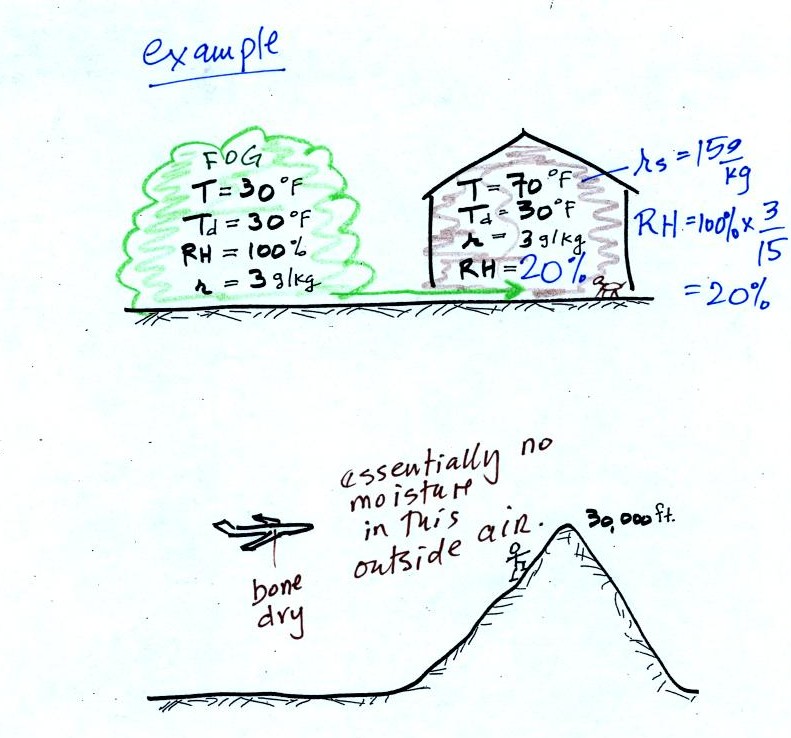

This sort of process ("squeezing" water vapor out of moist air by

cooling the air below its dew point) happens all the time. Here

are a couple of examples (p. 87 again)

The air in an

airplane comes from outside the plane. The air outside the plane

can be very cold (-60 F perhaps) and contains very little water

vapor (even if the -60 F air is saturated it would contain essentially

no water vapor). When brought inside and warmed to a

comfortable

temperature, the RH of the air in the plane will be very close

0%.

Passengers often complain of becoming dehydrated on long airplane

flights. The plane's ventilation system probably adds moisture to

the

air so that it doesn't get that dry.

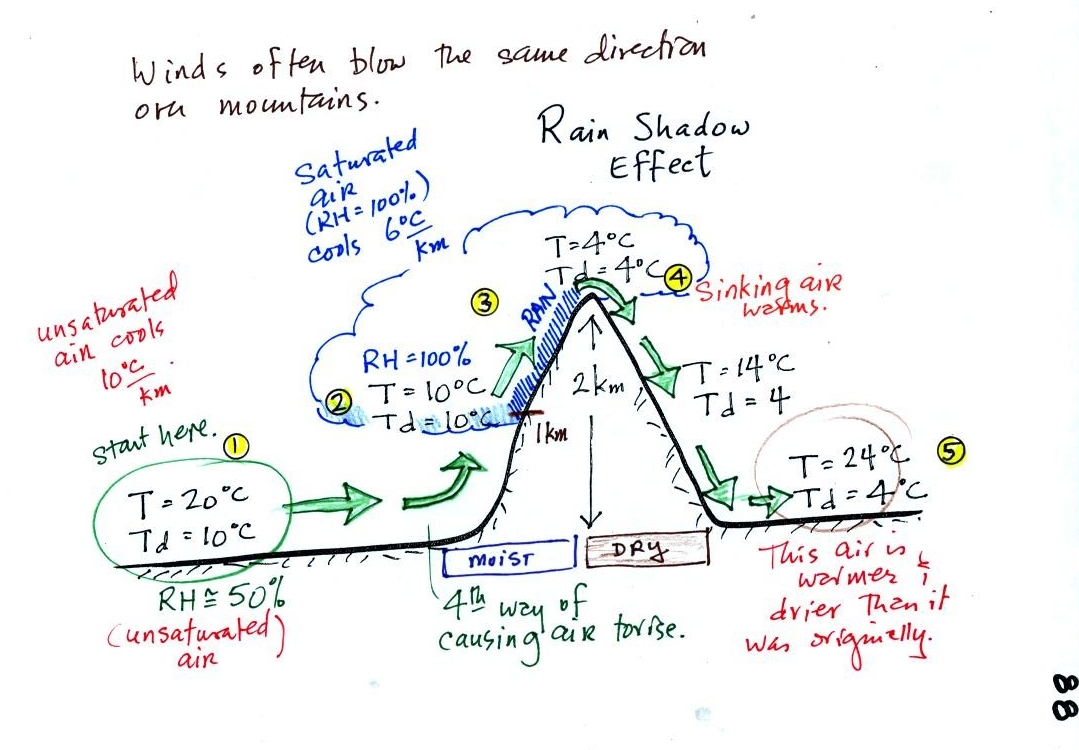

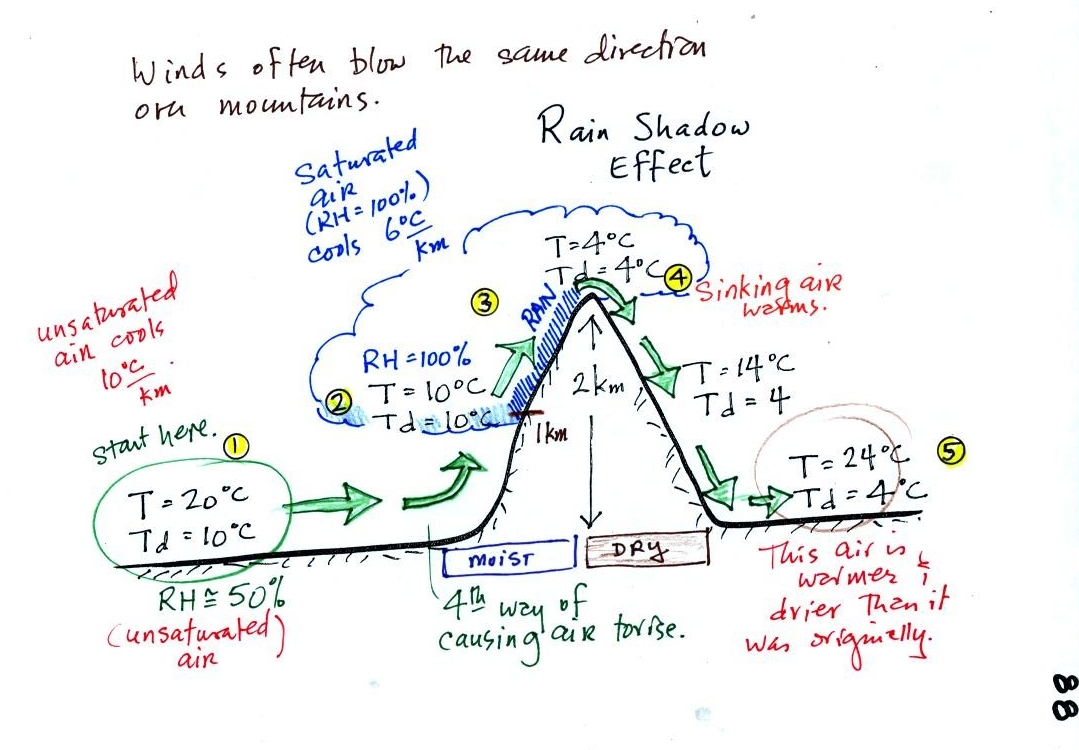

Here's a very important example, the rain shadow effect (p.

88 in the ClassNotes).

We didn't have enough time to cover this is class. I've included

it in the online notes because you might be able to use some of what

you learn here to answer Question #2 on the In-class Optional

Assignment.

We start with some moist but unsaturated air (RH is about

50%) at Point

1.

As it is moving toward the right the air runs into a mountain and

starts to rise (see the note below). Rising air expands and cools

(see the end of today's notes for more information on this

point). Unsaturated air

cools 10 C for every kilometer of altitude gain.

This is known as the dry adiabatic lapse rate. So in rising 1 km

the air will cool to 10 C which is the dew point.

The air becomes saturated at Point 2, you would see a cloud

appear. Rising saturated air cools at a slower rate than

unsaturated air (condensation of water vapor releases latent heat

energy, this warming partly offsets the cooling caused by

expansion). We'll use a value of 6 C/km (an average

value). The air cools from 10 C to 4

C in next kilometer up to the top of the mountain. Because the

air is being cooled below its dew point at Point 3, some of the water

vapor will condense and fall to the ground as rain. Moisture is

being removed from the air.

At Point 4 the air starts back down the right side of the

mountain. Sinking air is compressed and warms. As soon as

the air starts to

sink and warm, the relative humidity drops below 100% and the cloud

disappears. The sinking unsaturated air will warm at the 10 C/km

rate.

At Point 5 the air ends up warmer (24 C vs 20 C) and drier (Td =

4 C vs Td = 10 C) than when it started out. The downwind side of

the mountain is referred to as a "rain shadow" because rain is less

likely there than on the upwind side of the mountain. Rain is

less likely because the air is sinking and because the air on the

downwind side is drier than it was on the upslope side.

Most of the year the air that arrives in Arizona comes from the Pacific

Ocean. It

usually isn't very moist by the time it reaches Arizona because it has

travelled up and over the

Sierra Nevada mountains in

California and the Sierra Madre mountains further south in

Mexico. The air loses much of its moisture on the western slopes

of those mountains.

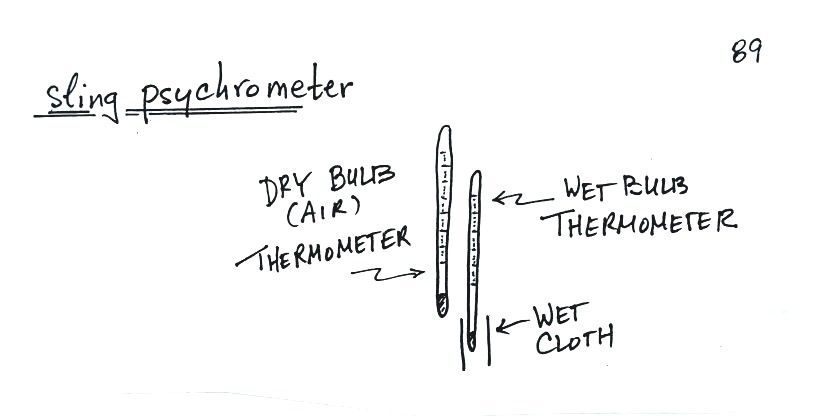

Next in

our potpourri of topics today was measuring

humidity. One of the ways of measuring humidity is to use a sling

(swing might be more descriptive) psychrometer.

A sling

psychrometer consists of two thermometers mounted

side by side. One is an ordinary thermometer, the other is

covered with a wet piece of cloth. To

make a humidity measurement you swing the psychrometer around for a

minute or two and then read the temperatures from the two

thermometers. The dry - wet thermometer (dry and wet bulb)

temperature difference can be

used to determine relative humidity and dew point.

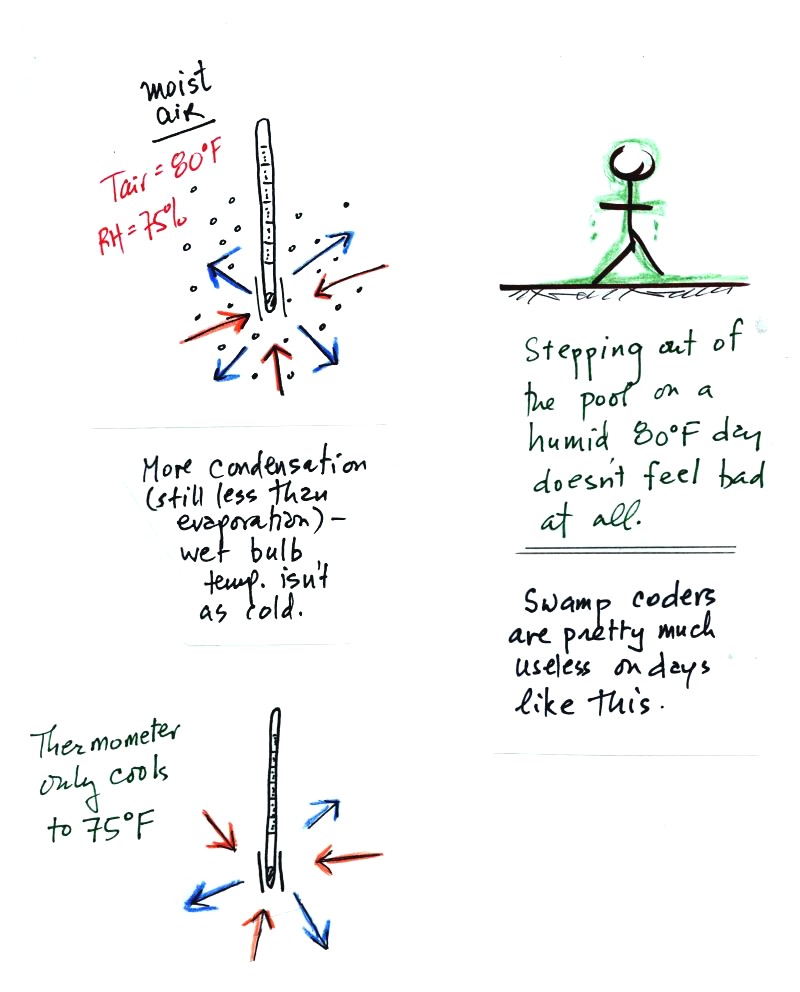

The evaporation is shown as blue arrows because this will cool the

thermometer. The same thing would happen if you were to step out

of a swimming pool on a warm dry day, you would feel cold. Swamp

coolers would work well on a day like this.

The figure at upper left also shows one arrow of condensation.

The amount or rate of condensation

depends on how much water vapor is

in the air surrounding the thermometer. In this case (low

relative humidity) there isn't much water vapor. The

condensation arrow is orange because the condensation will release

latent heat and warm the thermometer.

Because there is more evaporation (4 arrows) than condensation (1

arrow) the wet bulb thermometer will drop.

The wet thermometer will cool but it won't cool indefinitely. We

imagine that the wet bulb thermometer

has cooled to 60 F. Because the wet piece of cloth is cooler,

there is less evaporation. The wet bulb thermometer has cooled to

a temperature where the evaporation and condensation are in

balance. The thermometer won't cool any further.

You

would measure a large difference (20 F) between the dry and wet bulb

thermometers on a day like this when the air is relatively dry.

The air temperature is the same in this

example, but there is more

water vapor in the air.

You wouldn't feel as cold if you stepped out of a pool on a warm humid

day like this. Swamp coolers wouldn't provide much cooling on a

day like this.

There are four arrows of evaporation (because the water temperature is

still 80 F just as it was in the previous example) and three arrows now

of

condensation (due to the increased amount of water vapor in the air

surrounding the thermometer). The wet bulb thermometer will cool

but won't get as

cold as in the previous example.

The wet bulb thermometer might well only cool to 75 F. This might

be enough to lower the rate of evaporation (from 4 arrows to 3 arrows)

enough to bring it into

balance with the rate of condensation.

You would measure a small difference (5 F) between the dry and wet bulb

thermometers on a humid day like this.

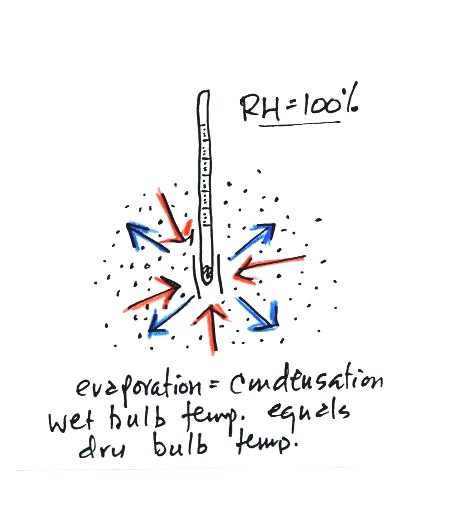

There won't be any difference in

the dry and wet bulb temperatures when

the

RH=100%. The rates at which water is evaporating and water vapor

is condensing are equal. That's one of the things that happens

when air is saturated. The dry and wet bulb thermometers would

both read 80 F.

The last thing we covered was the formation of dew, frost, and

something called frozen dew. The

figures below were redrawn after class to make them clearer.

It might be a little hard to figure out what is being

illustrated

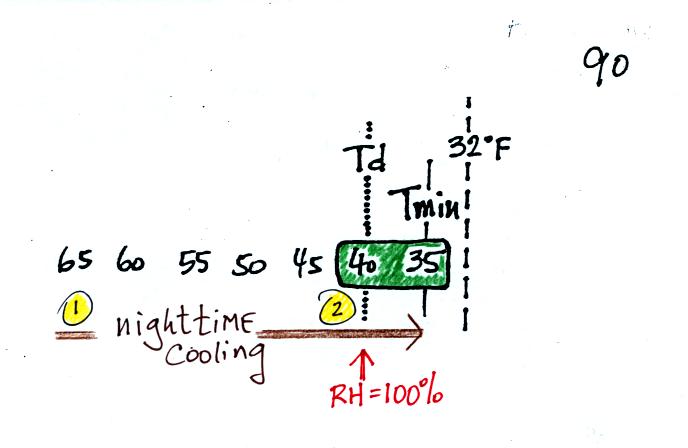

here. Point 1 is sometime in the early evening when the

temperature of the air at ground level is 65. By the next morning

the air has cooled to 35 F. When the air temperature reaches 40

F, the dew point, the relative humidity reaches 100% and water vapor

begins to condense onto the ground. You would find your newspaper

and your car covered with dew the next morning.

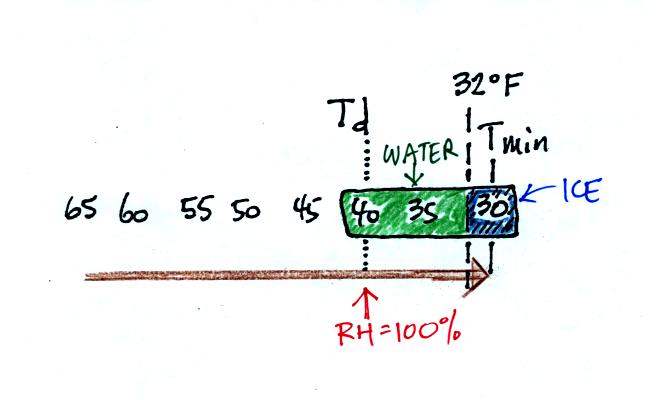

The next night is similar except that the nighttime

minimum

temperature drops below freezing. Dew forms and first covers

everything on the ground with water. Then the water freezes and

turns to ice. This isn't frost, rather

frozen dew. Frozen dew is often thicker and harder to scrape off

your car windshield than frost.

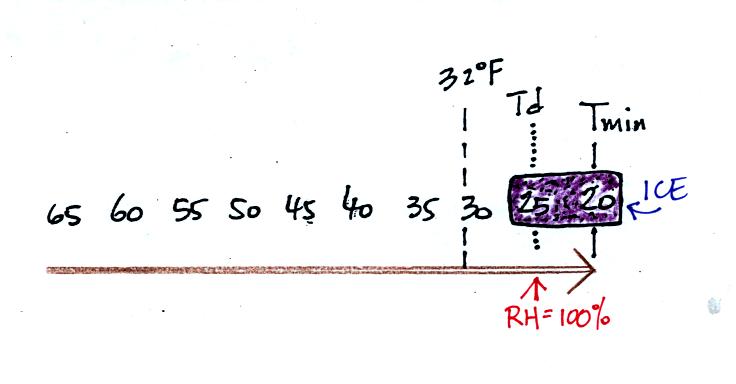

Now the dew point and the nighttime minimum temperature are both

below

freezing. When the RH reaches 100% water vapor turns directly to

ice (deposition). This is frost.

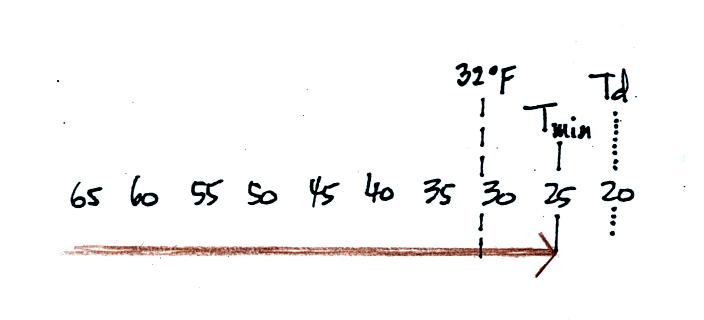

What happens on this night? Because the nighttime minimum

temperature never reaches the dew point and the RH never reaches 100%,

nothing would happen.