Mercury

barometers are used to measure atmospheric pressure. A mercury

barometer is really just a balance that can be used to weigh the

atmosphere. A basic understanding of how a mercury barometer

works is something that every college graduate should have.

You'll find most of what follows on p. 29 in the

photocopied Class Notes.

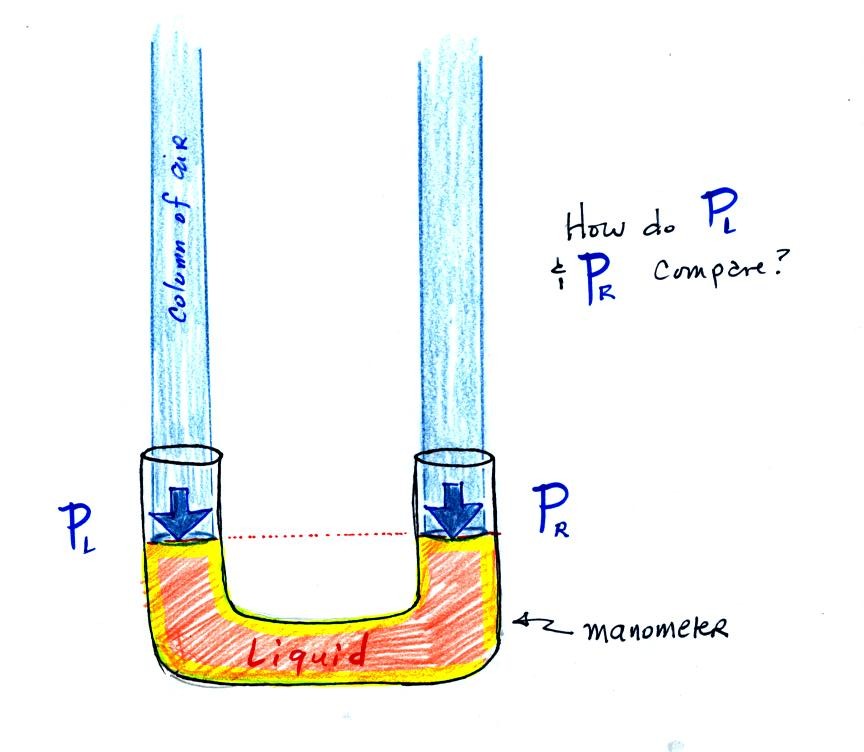

The instrument above ( a u-shaped

glass

tube filled with a

liquid of some kind) is a manometer and can be used to measure pressure

difference. The

two ends of the tube are open so that air can get inside and air

pressure can press on the liquid. Given that the liquid levels on

the two sides of the manometer

are equal, what could you about PL and PR?

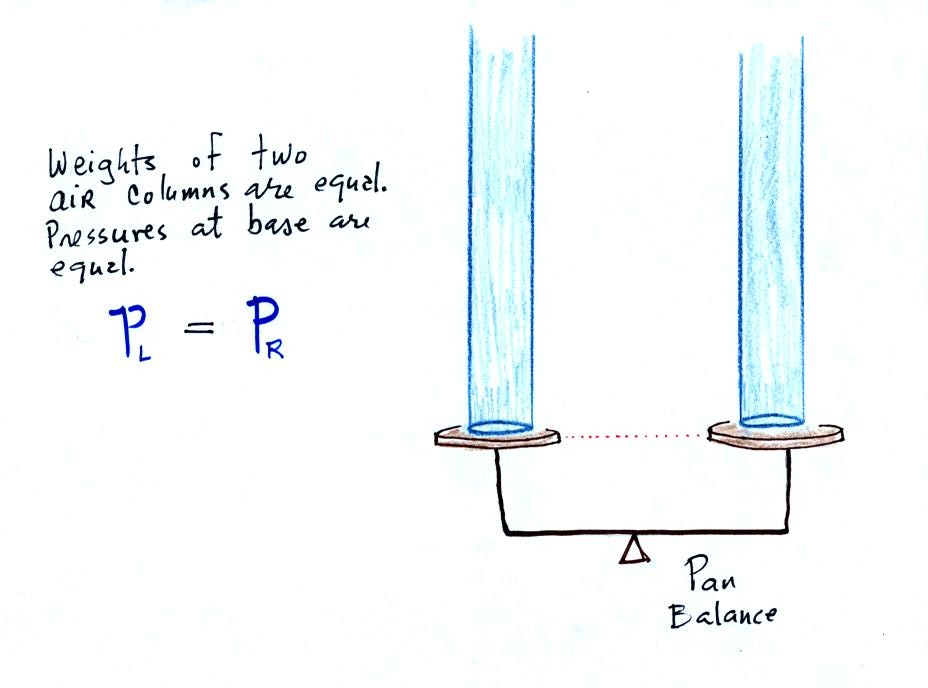

The liquid can slosh back and

forth just like the pans on a balance can move up and down. A

manometer really behaves just like a pan balance.

PL and PR

are equal (note

you don't really know what either pressure is just that they are equal).

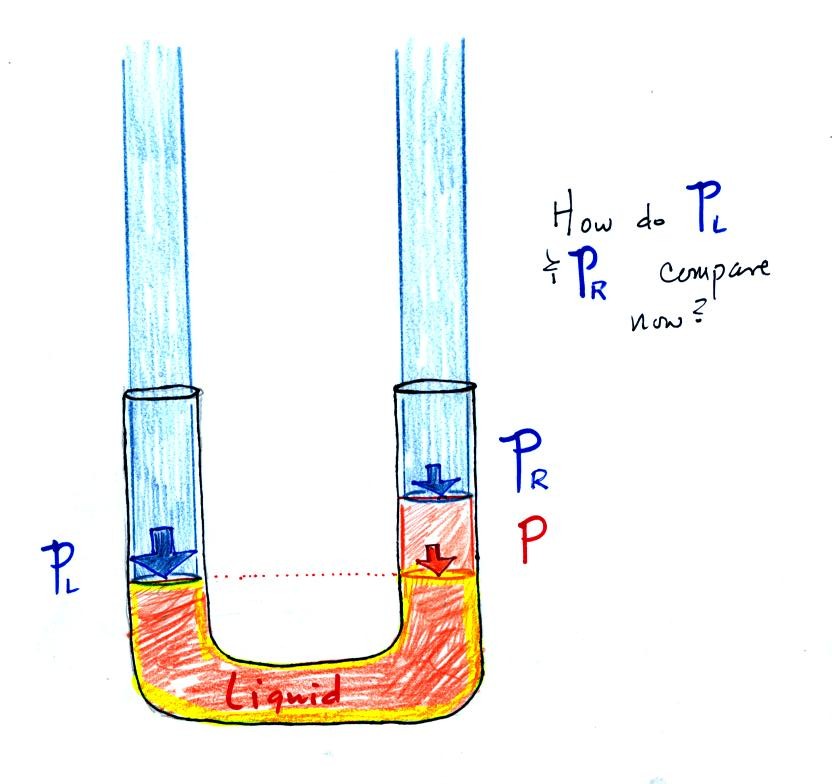

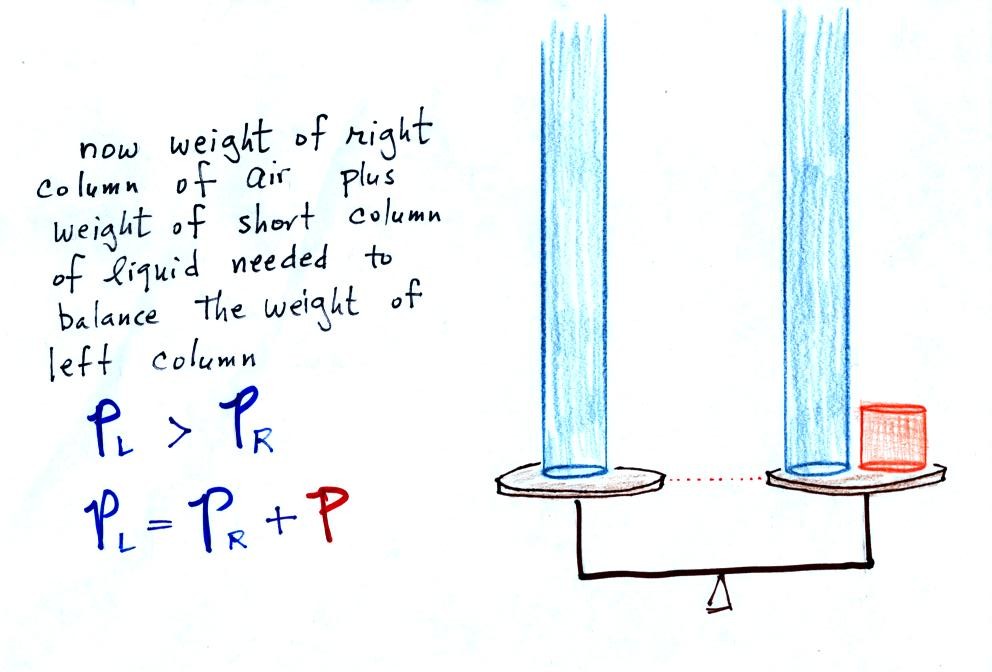

Now the situation is a little

different,

the

liquid levels

are no

longer equal. You probably realize that the air pressure on the

left, PL, is a little higher than the air pressure on the

right,

PR. PL is now being balanced by PR

+ P acting together. P

is the pressure produced by the weight of the extra fluid on the right

hand side of

the manometer (the fluid that lies above the dotted line). The

height of the column of extra

liquid provides a measure of the difference between PL and PR.

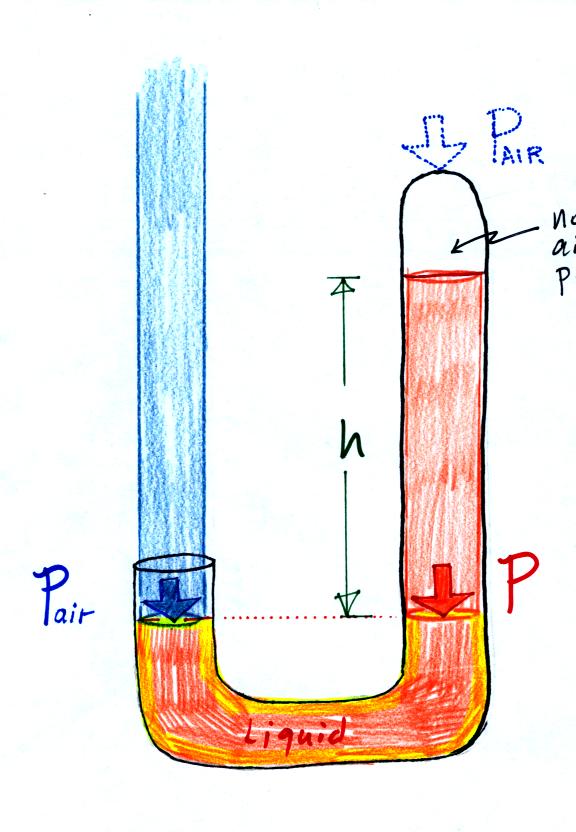

Next we will just go and close off

the right hand side of the

manometer.

Air pressure can't get into the

right tube any

more. Now at the level of the dotted line the balance is between

Pair and P (pressure by the extra liquid on the

right). If

Pair

changes, the height of the right column, h, will

change. You now have a barometer, an instrument that can measure

and monitor the atmospheric pressure. (some of the letters were cut off

in the upper right portion of the figure, they should read "no air

pressure")

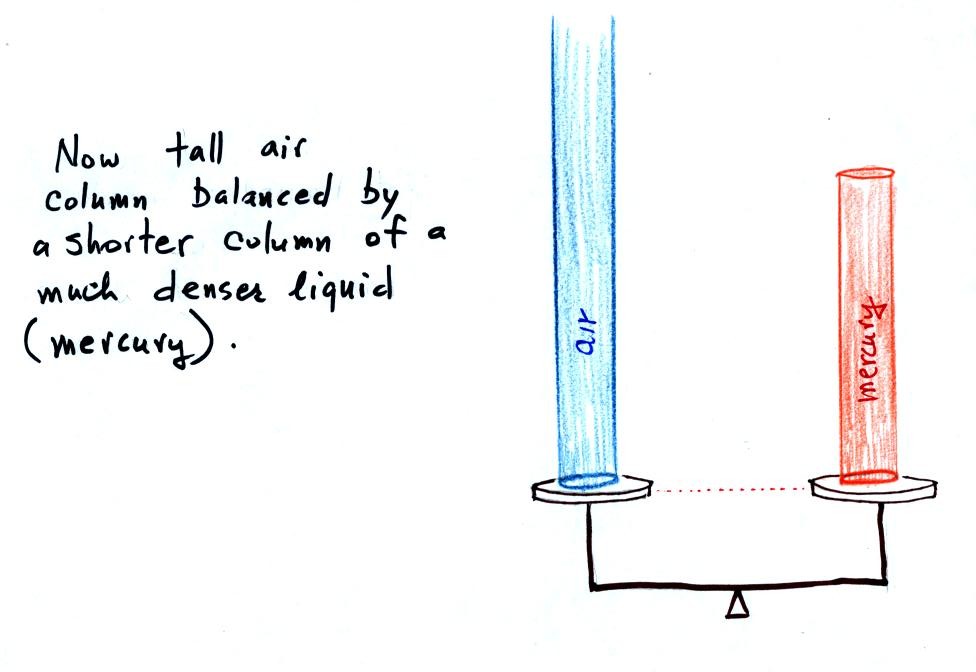

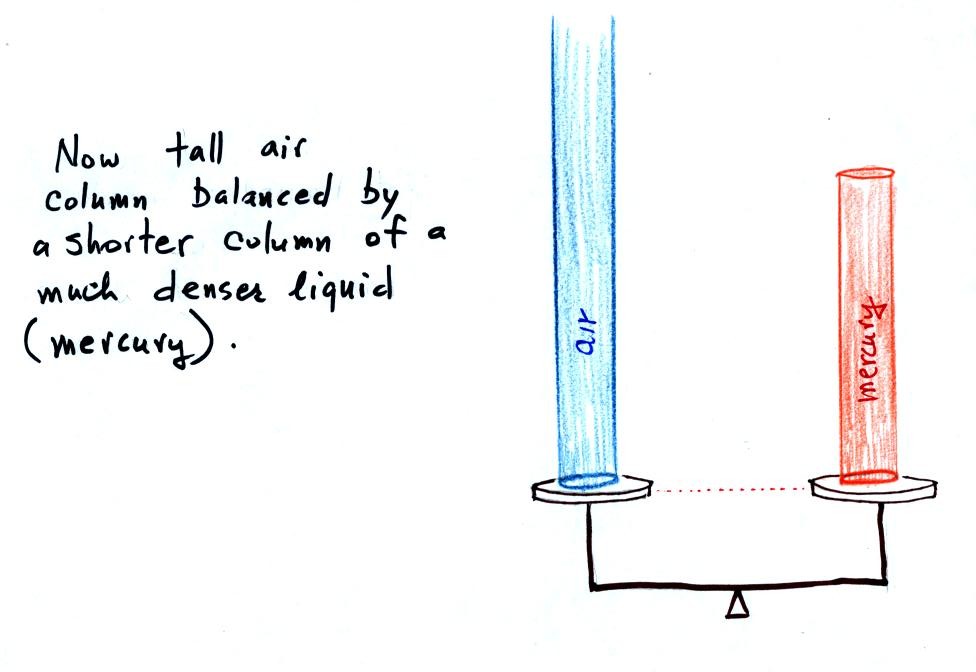

Barometers like this are usually

filled with mercury. Mercury is

a liquid. You need a liquid that can slosh back and forth in

response to changes in air pressure. Mercury is also very dense

which

means the barometer won't need to be as tall as if you used something

like water. A water barometer would need to be over 30 feet

tall. With mercury you will need only a 30 inch tall column to

balance the weight of the atmosphere at sea level under normal

conditions (remember the 30 inches of mercury pressure units mentioned

earlier). Mercury also has a low rate of

evaporation so you don't have much mercury gas at the top of the right

tube (it is the mercury vapor that would make a mercury spill in the

classroom dangerous).

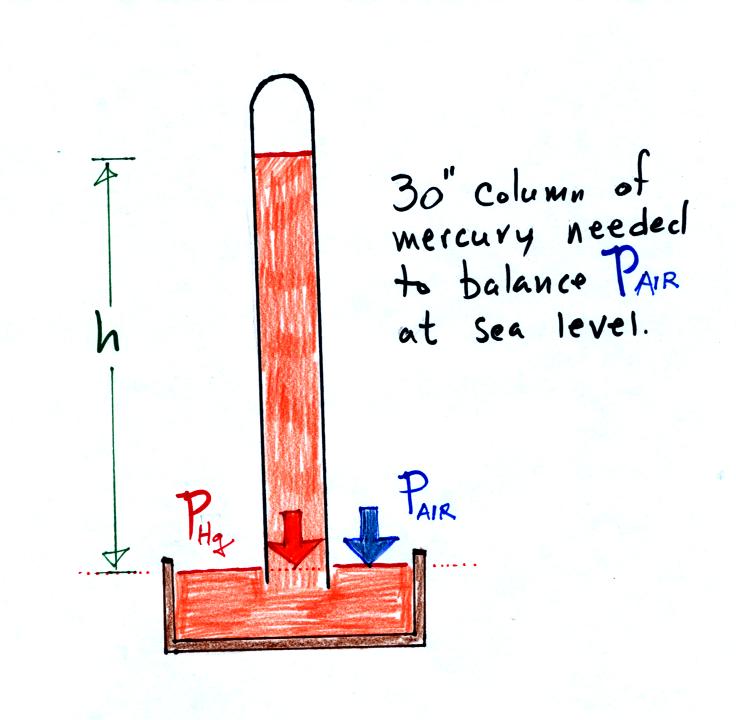

Finally here is a more conventional

barometer design.

The bowl of

mercury is usually covered in such a way that it can sense changes in

pressure but not evaporate and fill the room with poisonous mercury

vapor.

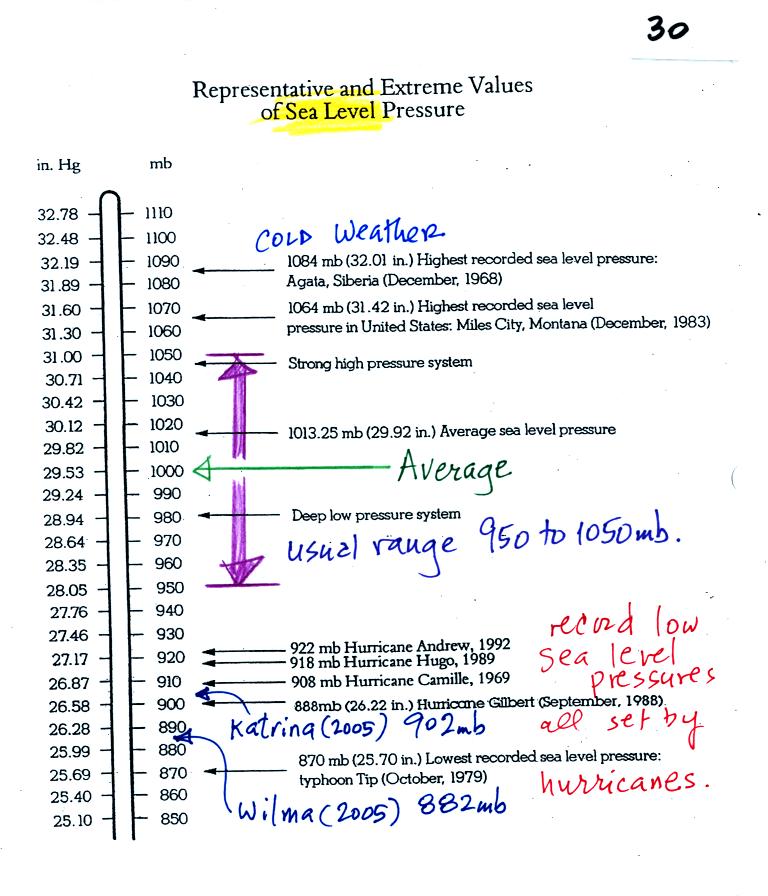

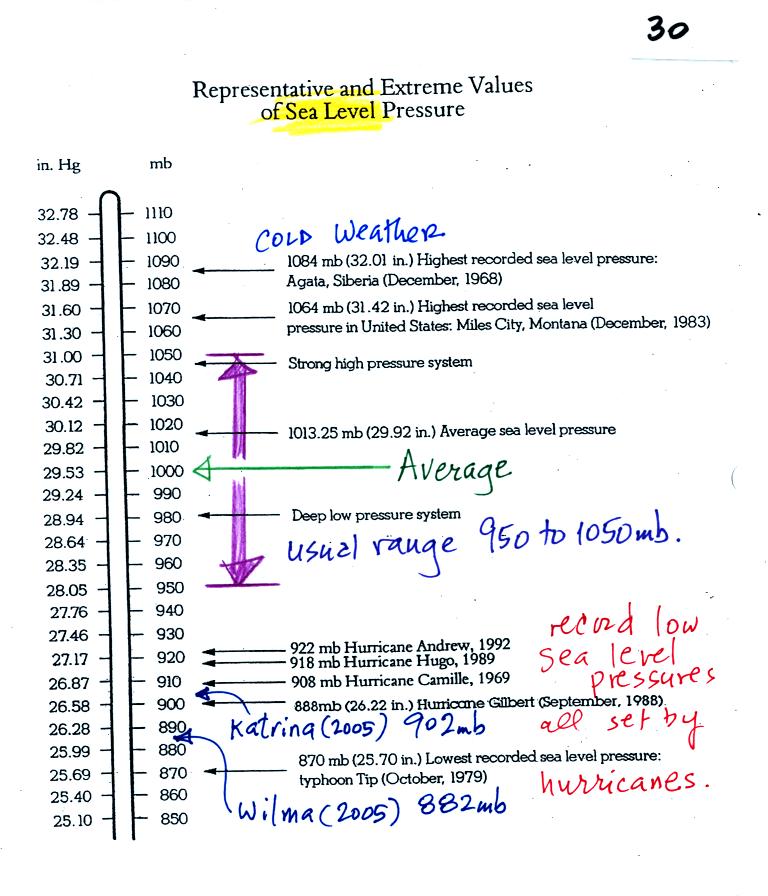

The figure above (p. 30 in the

photocopied Class Notes)

first

shows average sea level pressure values. 1000 mb or 30 inches of

mercury are close enough in this class.

Sea level pressures

usually fall between 950 mb and 1050 mb.

Record high sea level

pressure values occur during cold weather. The TV weather

forecast will often associated hot weather with high pressure.

They are generally referring to upper level high pressure (high

pressure at some level above the ground) rather than surface pressure.

Record low pressure

values have all been set by intense hurricanes (the record setting low

pressure is the reason these storms were so intense). Hurricane

Wilma in 2005 set a new record low sea level pressure reading for the

Atlantic. Hurricane Katrina had a pressure of 902 mb.

The following table lists some of the information on hurricane strength

from p. 146a in the photocopied ClassNotes. 3 of the 10 strongest

N. Atlantic hurricanes occurred in 2005.

Most

Intense North Atlantic Hurricanes

|

Most

Intense Hurricanes to hit the US Mainland

|

Wilma

(2005) 882 mb

Gilbert (1988) 888 mb

1935 Labor Day 892 mb

Rita (2005) 895 mb

Allen (1980) 899

Katrina (2005) 902

|

1935

Labor Day 892 mb

Camille (1969) 909 mb

Katrina (2005) 920 mb

Andrew (1992) 922 mb

1886 Indianola (Texas) 925 mb

|

Air pressure is a force that pushes

downward, upward, and

sideways.

If you fill a balloon with air and then push downward on it, you can

feel the air in the balloon pushing back (pushing upward). You'd

see the air in the balloon pushing sideways as well.

The air

pressure in the four tires on your automobile pushes down on the road

(that's something you would feel if the car ran over your foot) and

pushes upward

with enough force to keep the 1000 or 2000 pound vehicle off the

road.

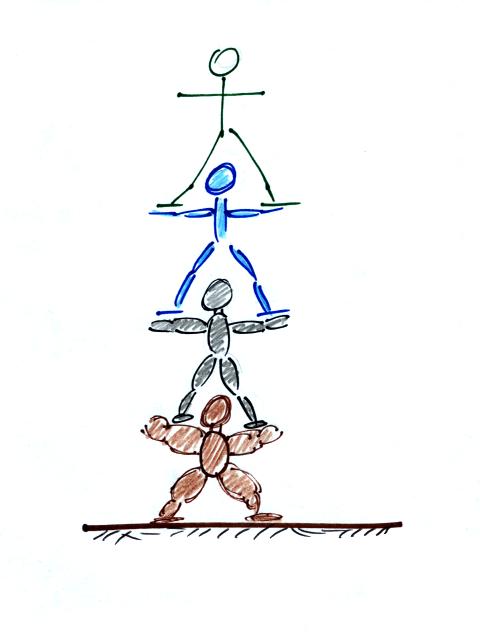

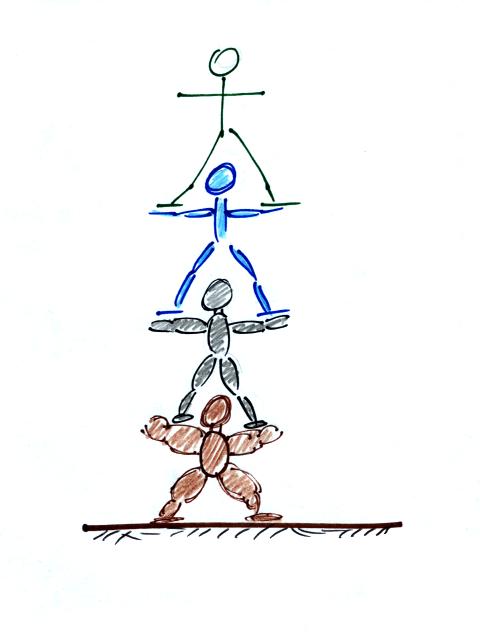

A "people pyramid" might help you

to understand what is going on in the atmosphere.

If the bottom person in the stack above were standing on a scale, the

scale would measure the total weight of all the people in the

pile. That's analogous to sea level pressure being determined by

the weight of the atmosphere above. The bottom person in the

picture above must be strong enough to support the weight of all the

people above. That equivalent to the bottom layer of the

atmosphere having enough pressure, pressure that points up down and

sideways, to support the weight of the air above.

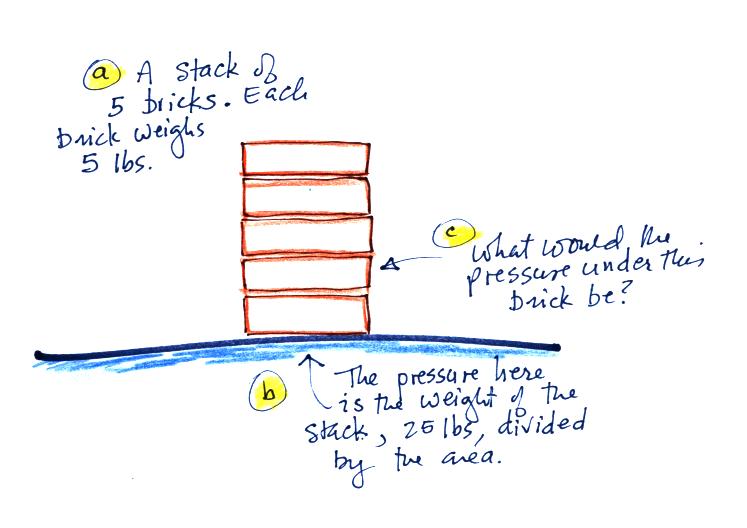

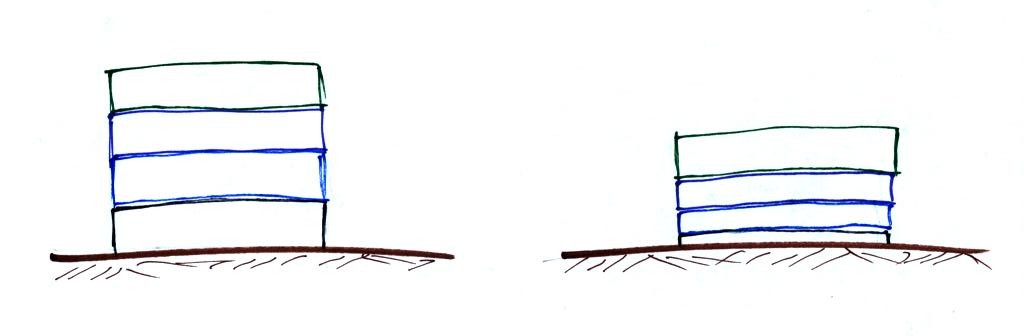

In class on Friday we used a stack of bricks to try to understand

that

pressure at any level in the atmosphere is determined by the weight of

the air overhead. Now we will imagine a stack of matresses

to

understand why air density decreases with increasing altitude.

Mattresses are

compressible. The mattress at the

bottom of the

pile is compressed the most by the weight of all the mattresses

above. The mattresses higher up aren't squished as much because

their

is less weight remaining above.

In the case of the atmosphere layers of air behave in just the

same way

as matresses.

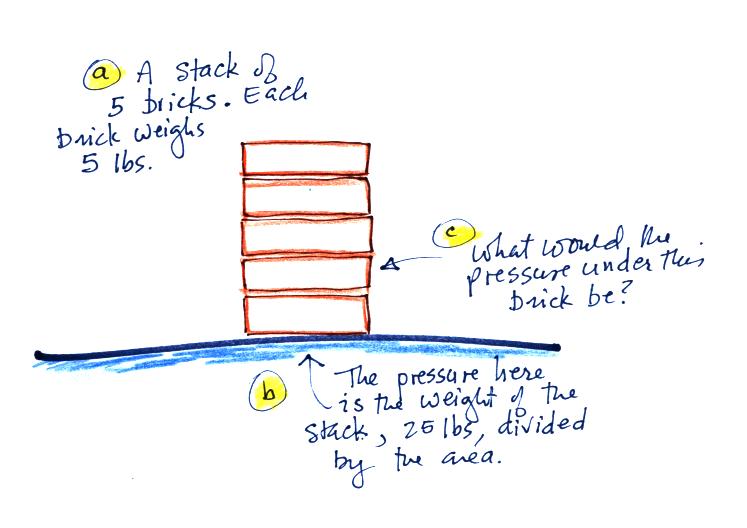

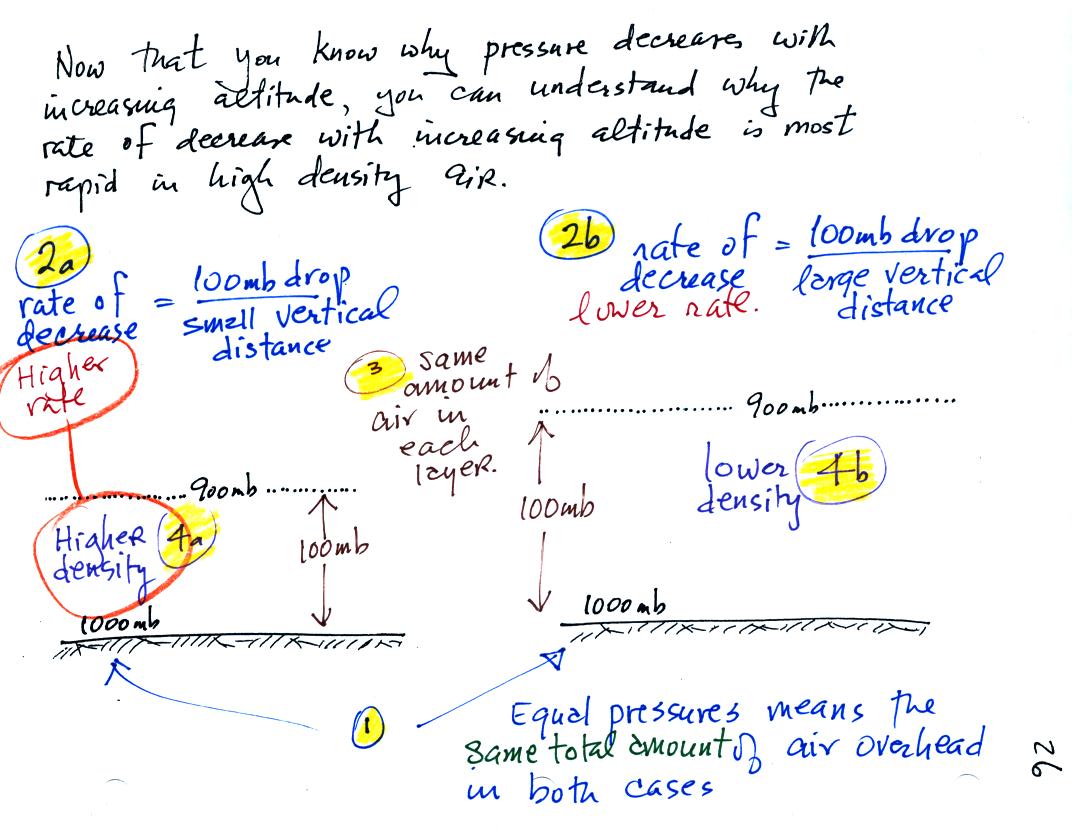

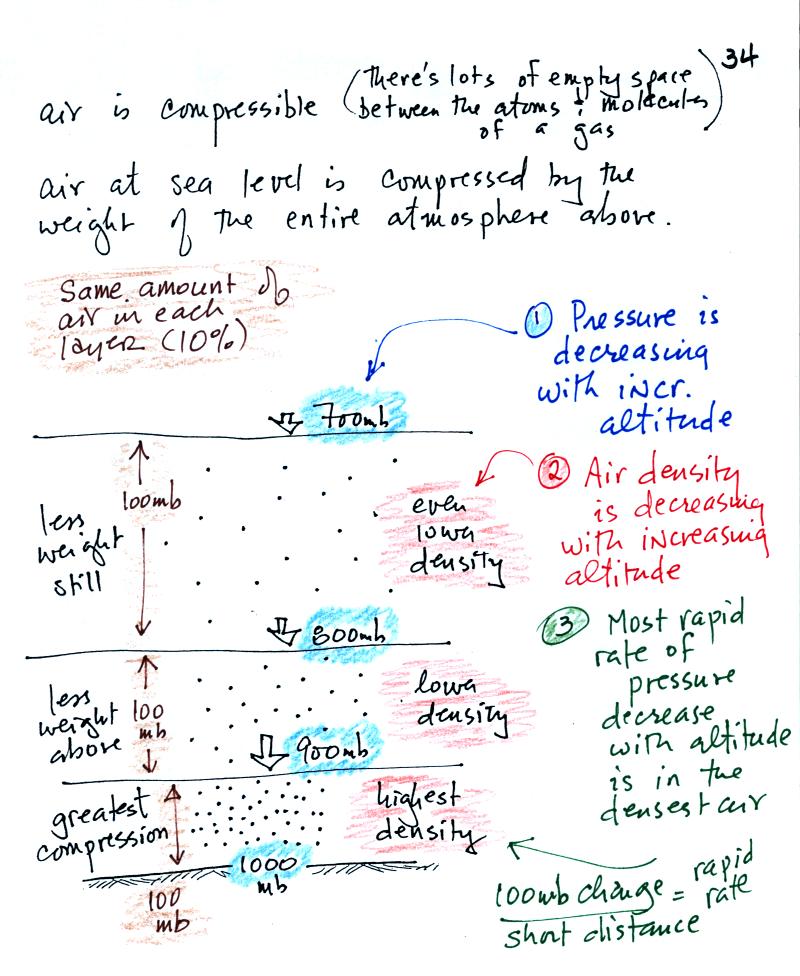

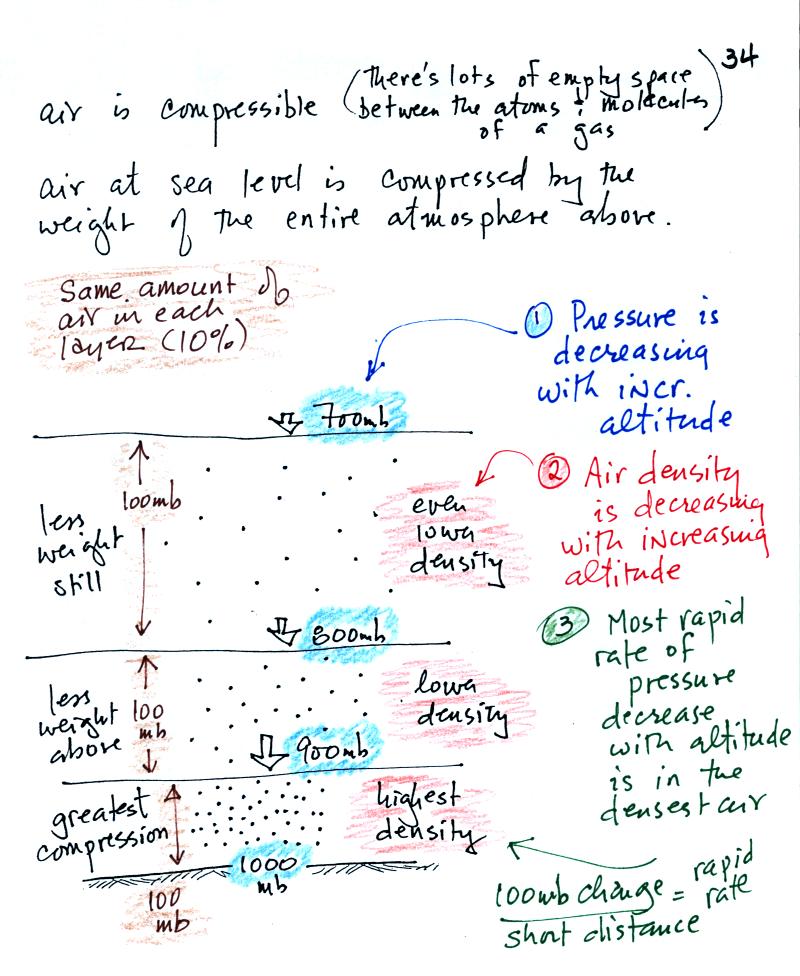

There's a lot of information in

this figure. It is worth

spending a minute or two looking at it and thinking about it.

1. You can first notice and remember that pressure

decreases

with increasing altitude. 1000 mb at the bottom decreases to 700

mb at the top of the picture.

Each layer of air contain the same amount (mass) of air. You

can

tell because the pressure decrease as you move upward through each

layer is the same (100 mb). Each layer contains 10% of the air in

the atmosphere.

2. The densest air is found in the bottom

layer. That is because each layer has the same amount of air

(same mass). The bottom layer is compressed the most and has the

smallest volume. Mass/( small volume)

gives a high density. The top layer has the same amount of air

but about twice the volume. It therefore has a lower density.

3. You again notice something that we covered earlier: the most

rapid

rate of pressure decrease with increasing altitude is in the densest

air in the bottom air layer. It takes almost twice the distance

for pressure to decrease from 800 mb to 700 mb in the top most layer

where the air density is low.

Class

concluded with a demonstration of the upward force

caused by air

pressure.

The demonstration is summarized on p. 35a in the photocopied

Classnotes.

Here's a little bit more detailed

and more complete explanation of

what is going on. First the case of a water balloon.

The figure at left shows air

pressure (red

arrows)

pushing on all

the

sides of the balloon. Because pressure decreases with increasing

altitude, the pressure pushing downward on the top of the balloon is a

little weaker (strength=14) than the pressure pushing upward at the

bottom of the

balloon (strength=15). The two sideways forces cancel each other

out. The

total effect of the pressure is a weak upward force (1 unit of upward

force shown at the top of the right

figure, you might have heard this called a bouyant force).

Gravity exerts a downward force on the water

balloon. In the figure at right you can see that the gravity

force (strength=10) is stronger than the upward pressure difference

force (strength=1). The

balloon falls as a result.

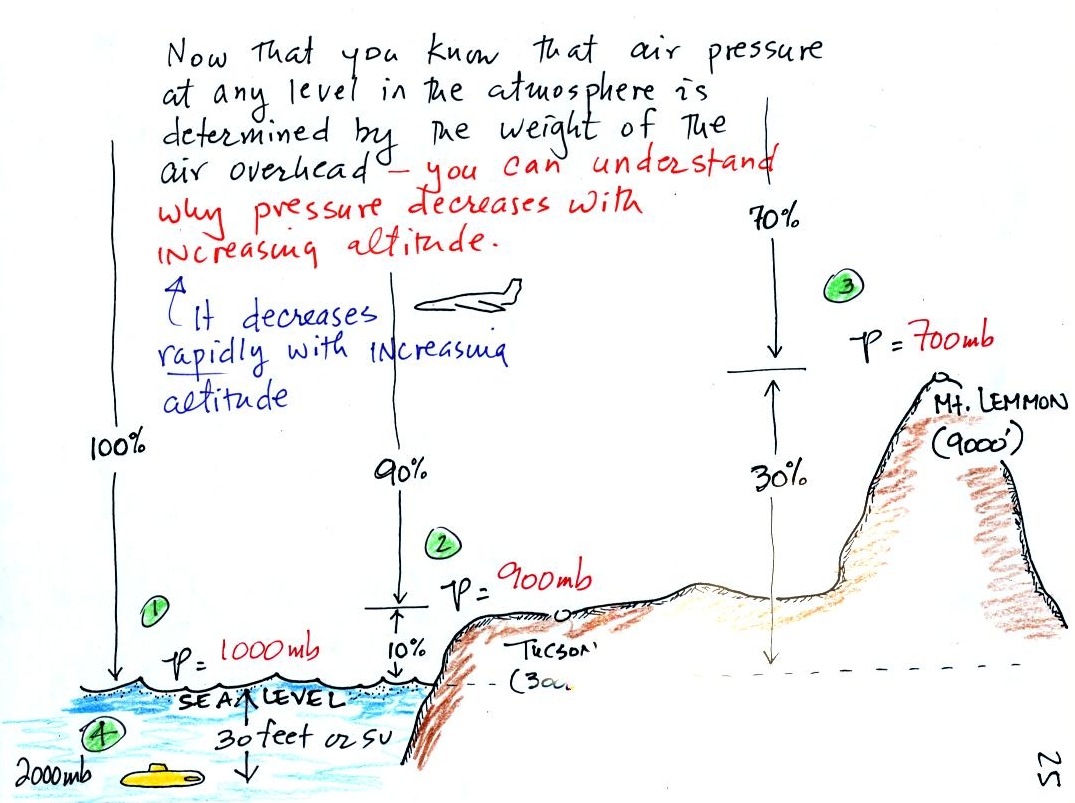

In the demonstration a wine glass is filled with water. A

small

plastic lid is used to cover the wine glass. You can then turn

the glass upside down without the water falling out. I

didn't actually do this part of the demonstration because I broke the

wine glass accidentally at the beginning of the period when I was

trying to get the music going.

All the same forces are shown again

in the left most

figure.

In

the right two figures we separate this into two parts. First

the water inside the glass isn't feeling the downward and sideways

pressure forces (because they're pushing on the glass). Gravity

still pulls downward on the water but the upward pressure force is able

to overcome the downward pull of gravity. The upward pointing

pressure force is used to overcome gravity not to cancel out the

downward pointing pressure force.

I normally repeat the demonstration using a 4 Liter flash (more

than a

gallon of water, more than 8 pounds of water). Fortunately that

was still intact. The upward

pressure force was still able to keep the water in the flask (much of

the weight of the water is pushing against the sides of the flask which

the instructor was supporting with his arms).

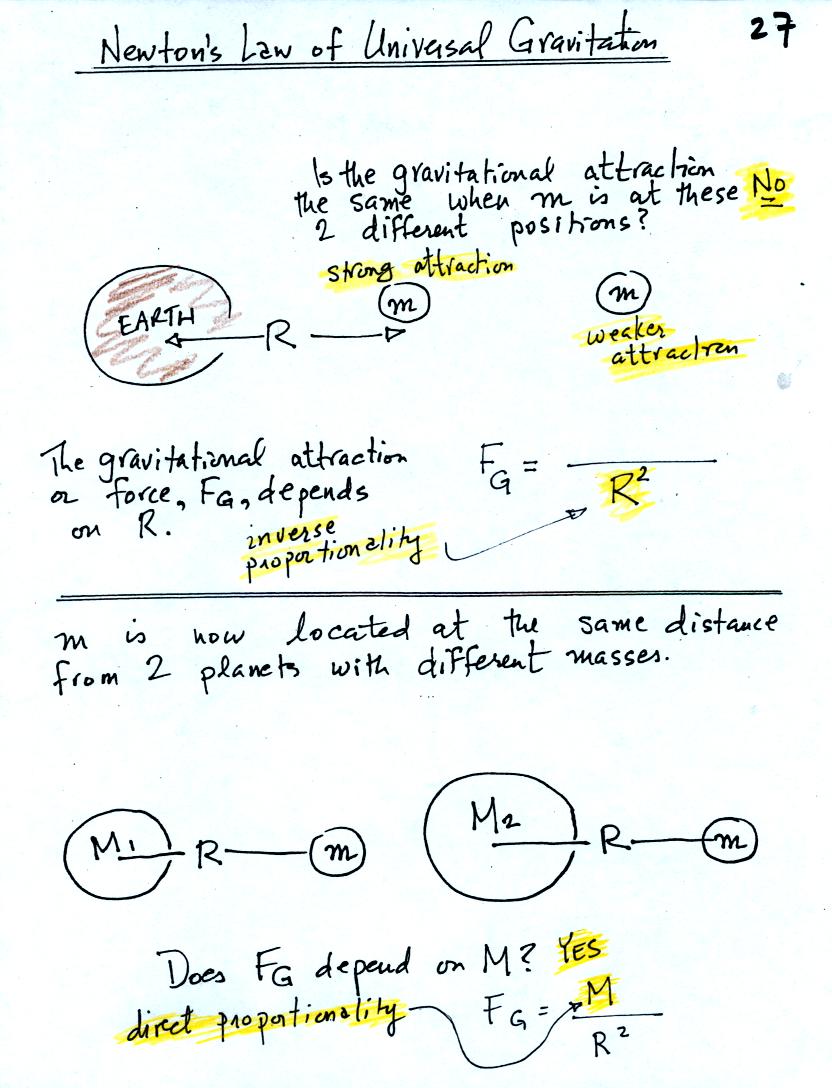

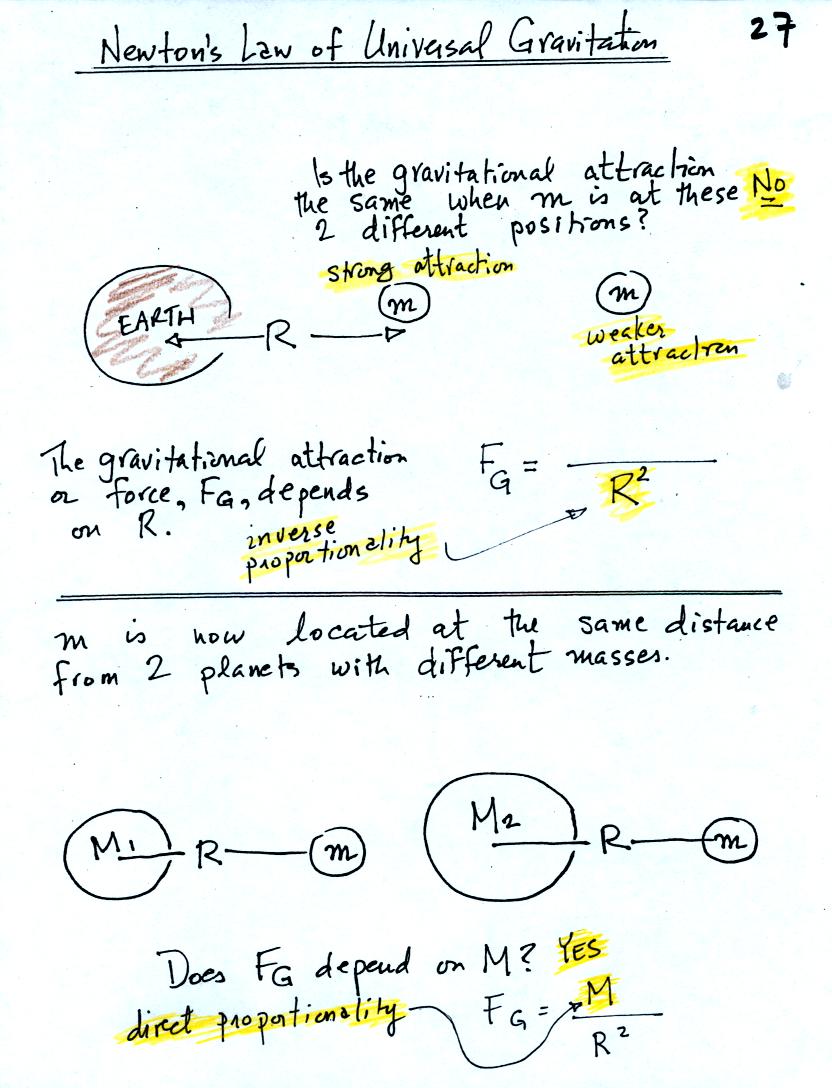

Newton's

Law of Universal Gravitation is an equation that allows you to

calculate the gravitational attraction between two objects. We didn't work through most of the

details below in class. With a little thought you can

appreciate and

understand why certain variables appear in Newton's Law and why they

appear in either the numerator (direct proportionality) or in the

denominator (inverse proportionality).

The gravitational attraction

between two

objects (M and m in

the figures) depends

first of

all

on the distance separating the objects. The gravitational

force becomes weaker the further away the two objects are from each

other. In the bottom

picture above and the top figure below we see that the attractive force

also depends on the masses of the two objects. The masses go in

the numerator.

The complete formula is shown in

the middle of the page

above. G

is a constant. On the surface of the earth G, M, and R don't

change. The gravitational acceleration, g, is just the

quantity [G times Mearth

divided by ( Rearth )2 ]. To determine the

weight (on the earth's surface) of an object

with mass m you simply multiply m x g.

Down at the bottom of the page are the Metric and English units of

mass

and weight. You have probably heard of pounds, grams, and

kilograms. You might not have heard of dynes and Newtons.

Most people have never heard of slugs.