Tops of thunderstorms (anvil

clouds) viewed from the Space

Shuttle (source).

The

cloud

tops are about 15 km high and flatten out when they reach the

top of the troposphere. Even powerful thunderstorms (over Brazil)

like these aren't able to push into the very stable air in the

stratosphere.

Class started with a little practice decoding weather data plotted using the station model notation. Green cards were handed out for the first time this semester to serve as motivation.

Class started with a little practice decoding weather data plotted using the station model notation. Green cards were handed out for the first time this semester to serve as motivation.

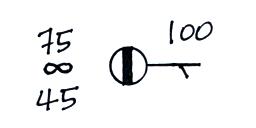

What information is shown

here? You'll find the answers at the end of today's notes.

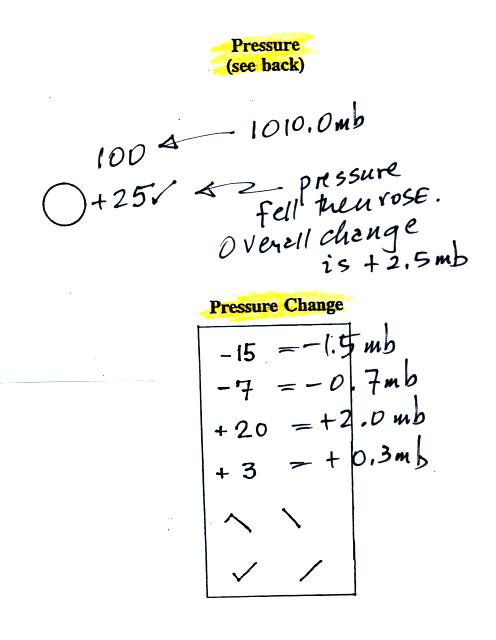

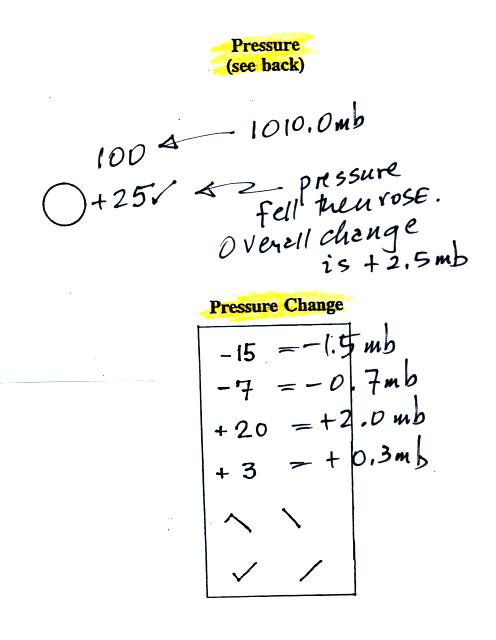

The sea level pressure is shown above and to the right of the center circle. Decoding this data is a little "trickier" because some information is missing. We'll look at this in more detail momentarily.

Pressure change data (how the pressure has changed during the preceding 3 hours) is shown to the right of the center circle. You must remember to add a decimal point. Pressure changes are usually pretty small.

Here are some links to surface weather maps with data plotted using the station model notation: UA Atmos. Sci. Dept. Wx page, National Weather Service Hydrometeorological Prediction Center, American Meteorological Society.

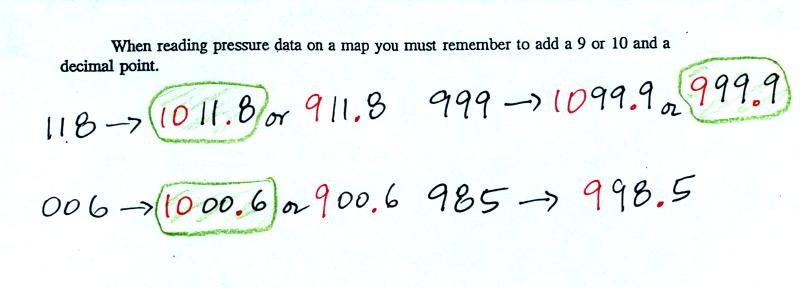

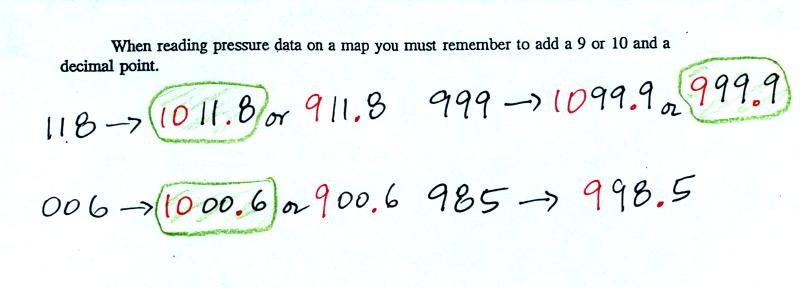

Here's how you can decode the pressure data.

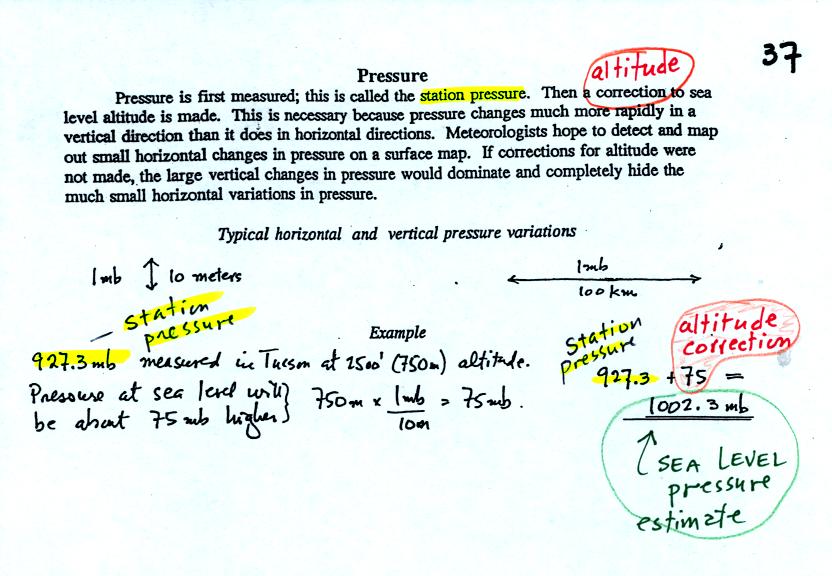

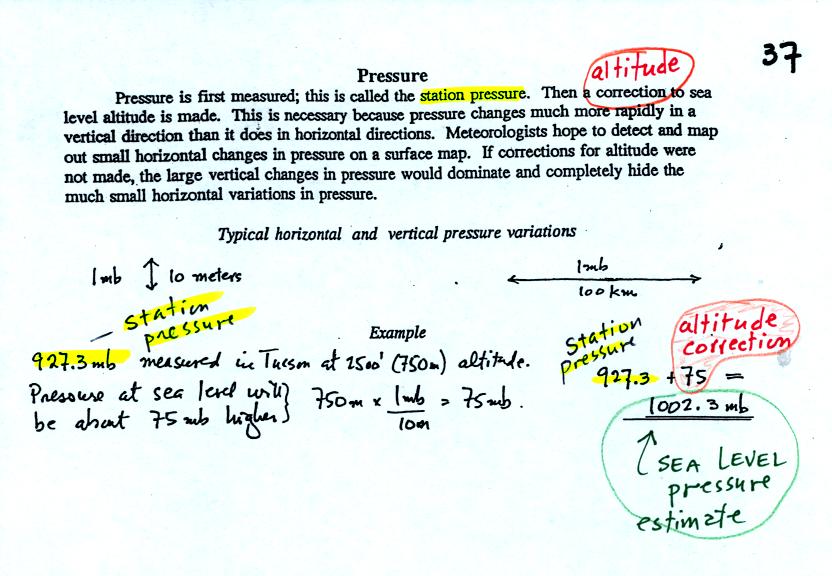

Meteorologists hope to map out small horizontal pressure changes on surface weather maps (that produce wind and storms). Pressure changes much more quickly when moving in a vertical direction. The pressure measurements are all corrected to sea level altitude to remove the effects of altitude. If this were not done large differences in pressure at different cities at different altitudes would completely hide the smaller horizontal changes.

In the example above, a station pressure value of 927.3 mb was measured in Tucson. Since Tucson is about 750 meters above sea level, a 75 mb correction is added to the station pressure (1 mb for every 10 meters of altitude). The sea level pressure estimate for Tucson is 927.3 + 75 = 1002.3 mb. This is also shown on the figure below

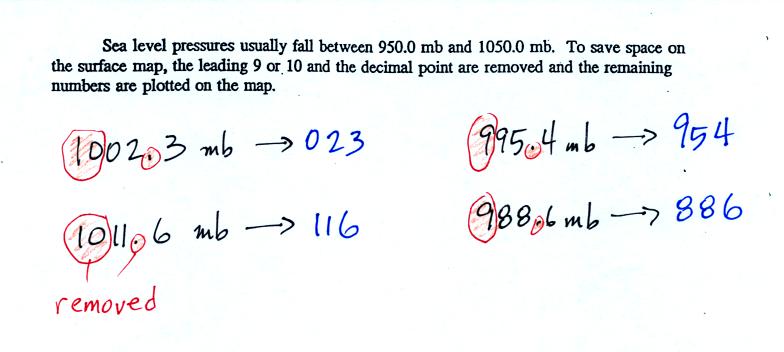

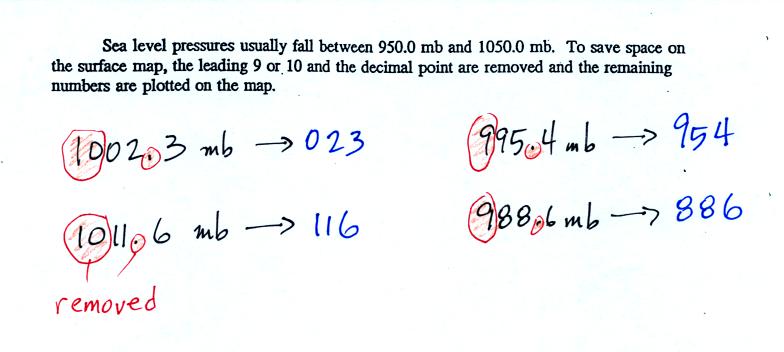

To save room, the leading 9 or 10 on the sea level pressure value and the decimal point are removed before plotting the data on the map. For example the 10 and the . in 1002.3 mb would be removed; 023 would be plotted on the weather map (to the upper right of the center circle). Some additional examples are shown above.

When reading pressure values off a map you must remember to add a 9 or 10 and a decimal point. For example

118 could be either 911.8 or 1011.8 mb. You pick the value that falls between 950.0 mb and 1050.0 mb (so 1011.8 mb would be the correct value, 911.8 mb would be too low).

Another important piece of information on a surface map is the time the observations were collected. Time on a surface map is converted to a universally agreed upon time zone called Universal Time (or Greenwich Mean Time, or Zulu time). That is the time at 0 degrees longitude. There is a 7 hour time zone difference between Tucson (Tucson stays on Mountain Standard Time year round) and Universal Time. You must add 7 hours to the time in Tucson to obtain Universal Time.

Here are some examples (not done in class)

to convert from MST (Mountain Standard Time) to UT (Universal Time)

2:45 pm MST:

9:05 am MST:

to convert from UT to MST

18Z:

02Z:

if we subtract the 7 hour time zone correction we will get a negative number.

We will add 24:00 to 02:00 UT then subtract 7 hours

02:00 + 24:00 = 26:00

26:00 - 7:00 = 19:00 MST on the previous day

2 hours past midnight in Greenwich is 7 pm the previous day in Tucson

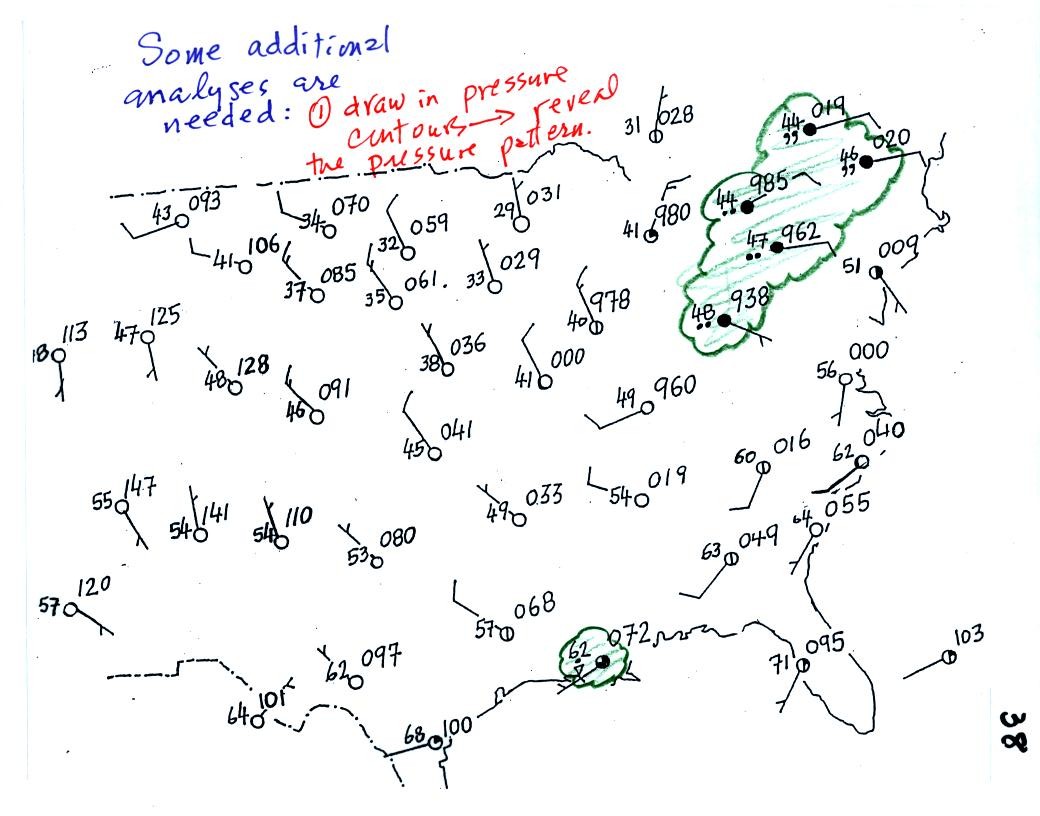

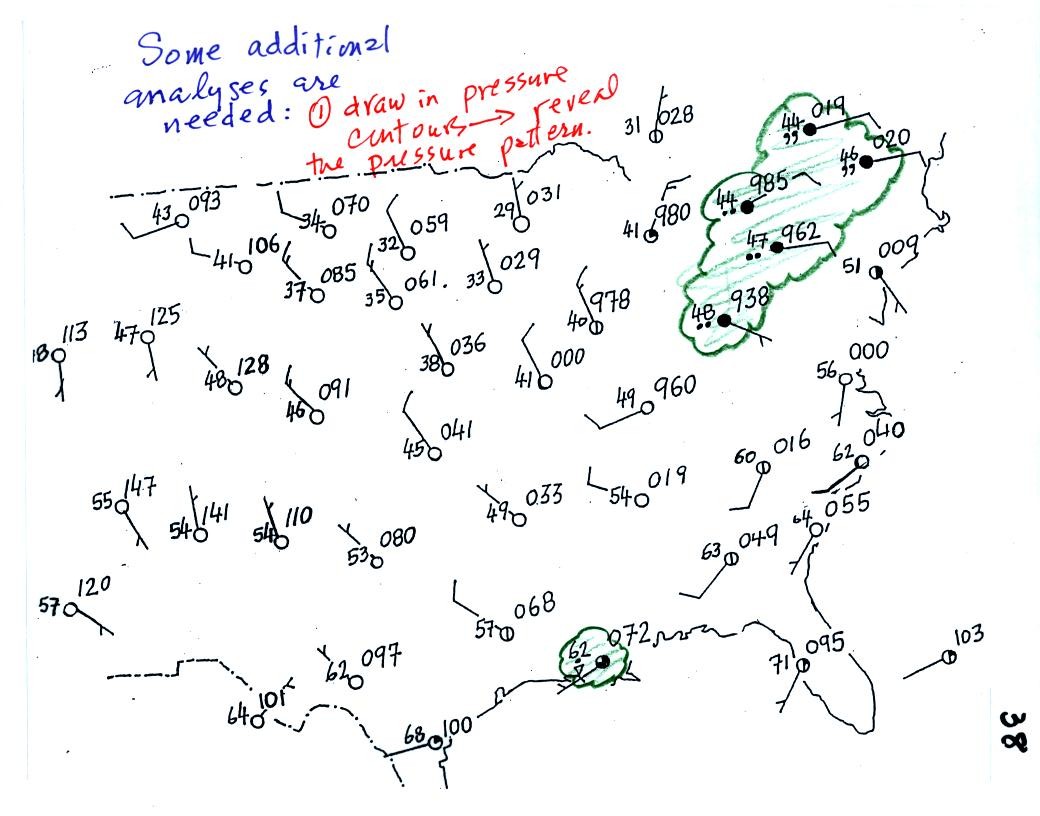

Plotting the surface weather data on a map is just the beginning. For example you really can't tell what is causing the cloudy weather with rain (the dot symbols are rain) and drizzle (the comma symbols) in the NE portion of the map above or the rain shower along the Gulf Coast. Some additional analysis is needed. A meteorologist would usually begin by drawing some contour lines of pressure to map out the large scale pressure pattern. We will look first at contour lines of temperature, they are a little easier to understand (easier to decode the plotted data and temperature varies across the country in a fairly predictable way).

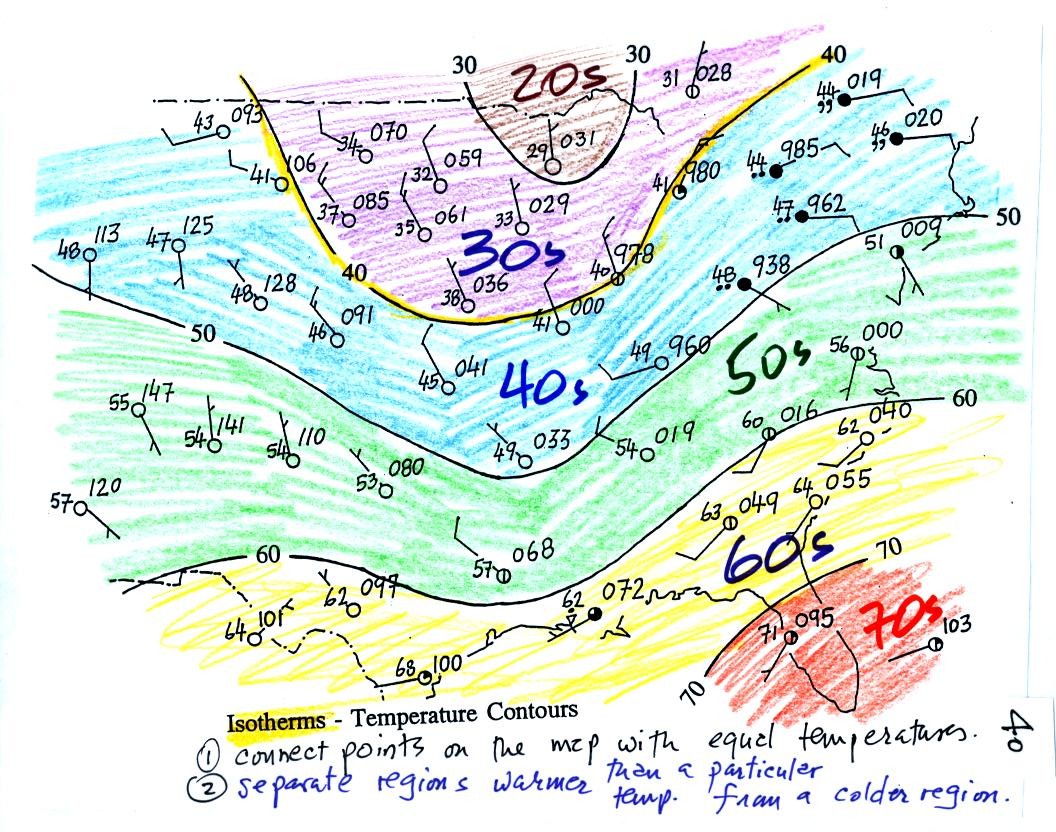

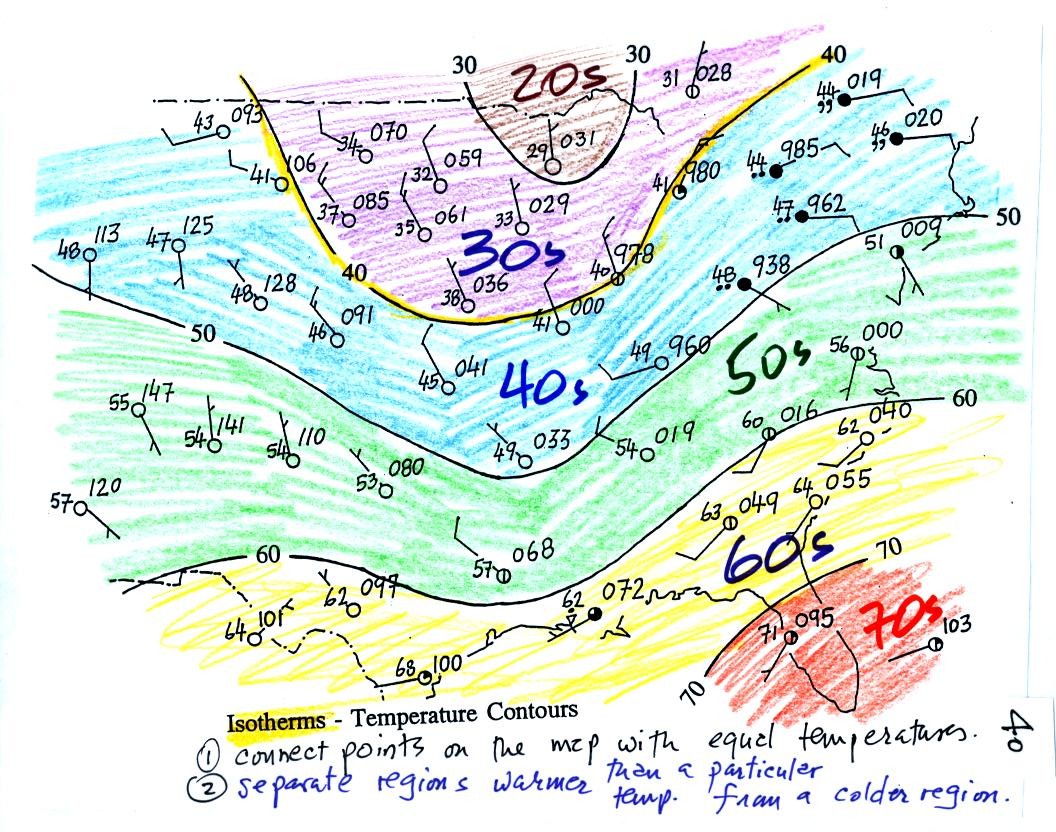

Isotherms, temperature contour lines, are usually drawn at 10 F intervals. They do two things: (1) connect points on the map that all have the same temperature, and (2) separate regions that are warmer than a particular temperature from regions that are colder. The 40o F isotherm highlighted in yellow above passes through a city which is reporting a temperature of exactly 40o. Mostly it goes between pairs of cities: one with a temperature warmer than 40o and the other colder than 40o. Temperatures generally decrease with increasing latitude: warmest temperatures are usually in the south, colder temperatures in the north.

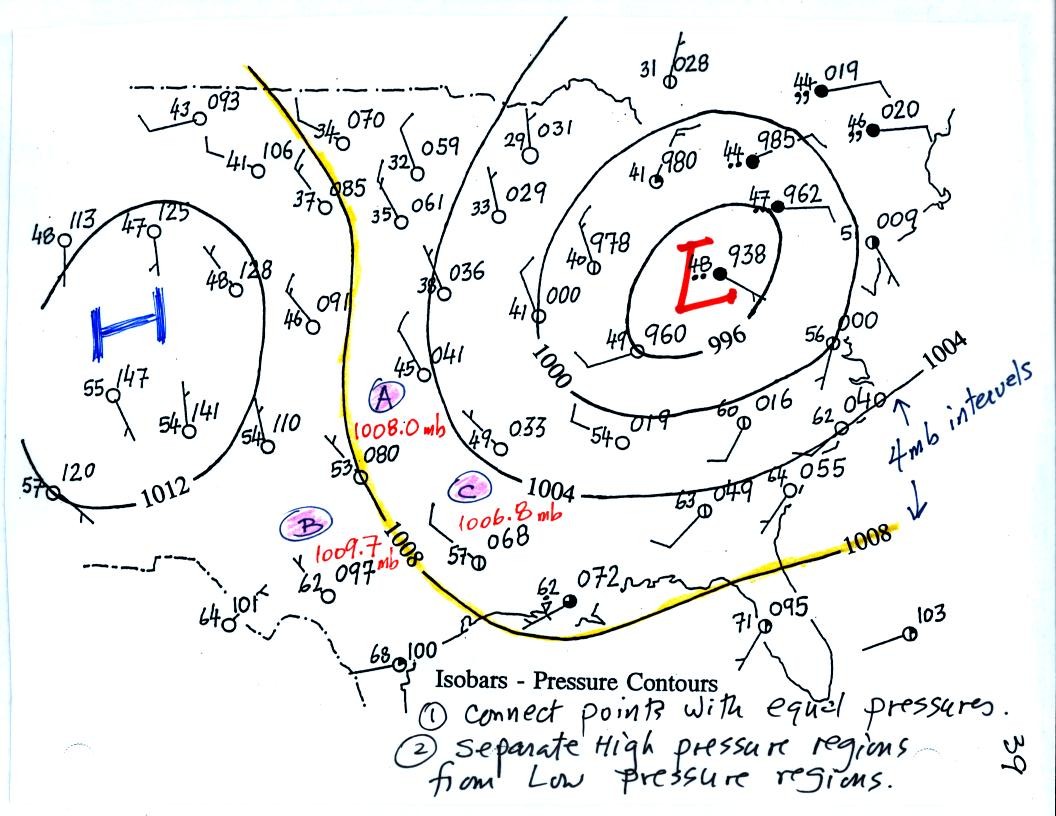

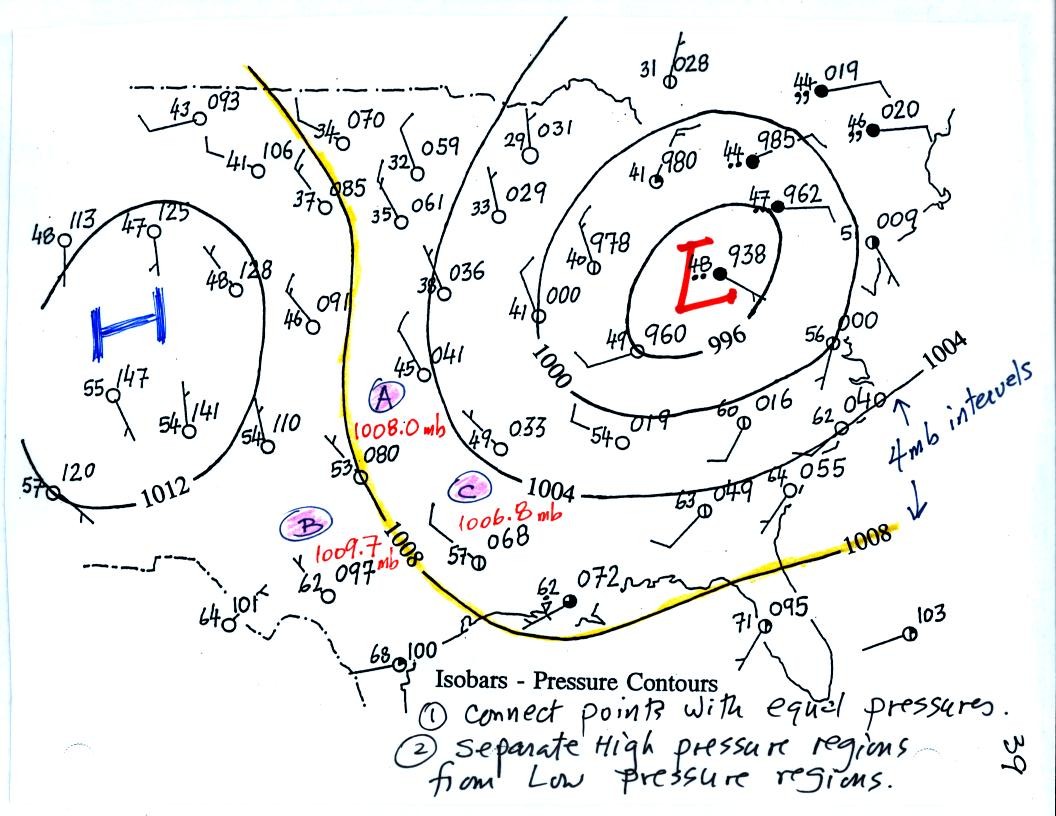

Now the same data with isobars drawn in. Again they separate regions with pressure higher than a particular value from regions with pressures lower than that value. Isobars are generally drawn at 4 mb intervals. Isobars also connect points on the map with the same pressure. The 1008 mb isobar (highlighted in yellow) passes through a city at Point A where the pressure is exactly 1008.0 mb. Most of the time the isobar will pass between two cities. The 1008 mb isobar passes between cities with pressures of 1009.7 mb at Point B and 1006.8 mb at Point C. You would expect to find 1008 mb somewhere in between those two cites, that is where the 1008 mb isobar goes.

The pattern on this map is very different from the pattern of isotherms. On this map the main features are the circular low and high pressure centers.

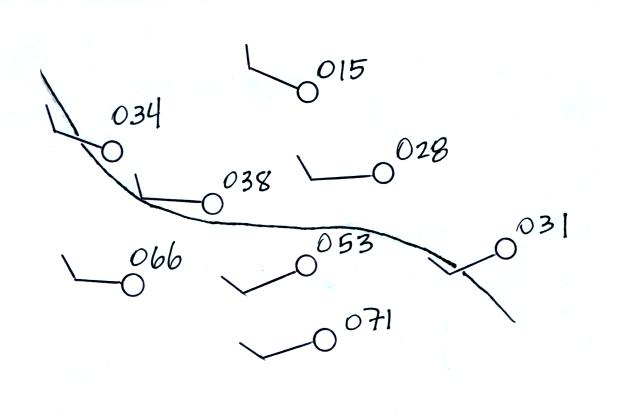

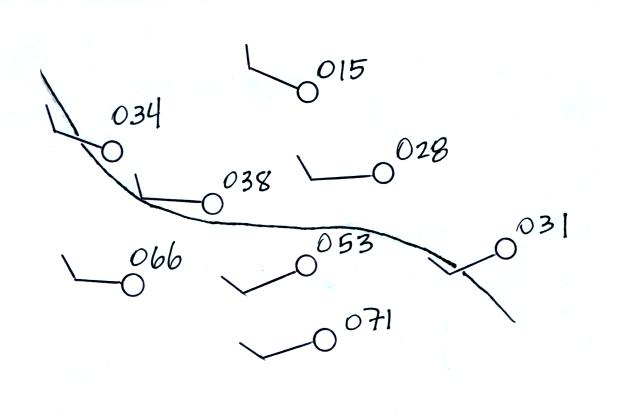

Here's a little practice. Is this the 1000, 1002, 1004,

1006, or 1008 mb isobar? (you'll find the answer at the end of today's

notes)

Just locating closed centers of high and low pressure will already tell you a lot about the weather that is occurring in their vicinity.

1.

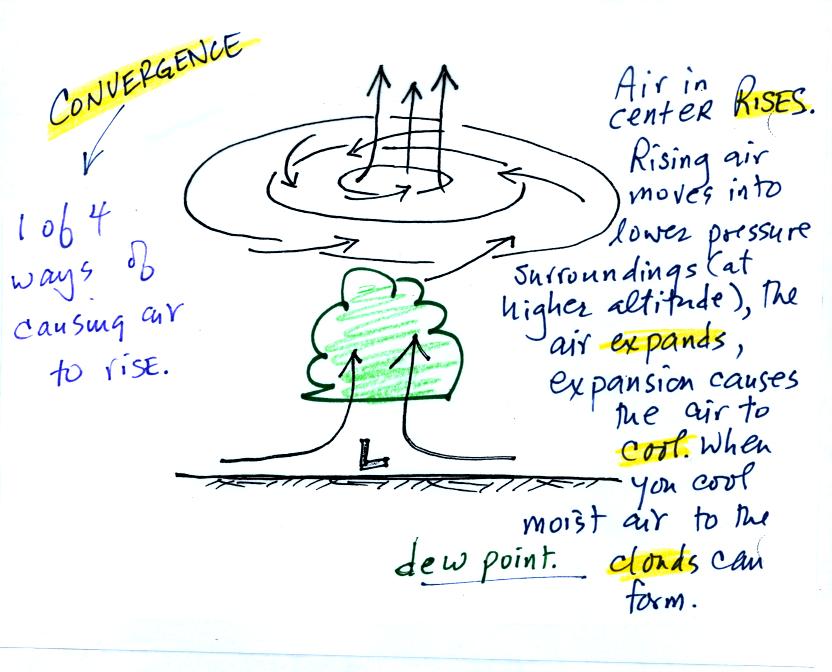

We'll start with the large nearly circular centers of High and Low pressure. Low pressure is drawn below. These figures are more neatly drawn versions of what we did in class.

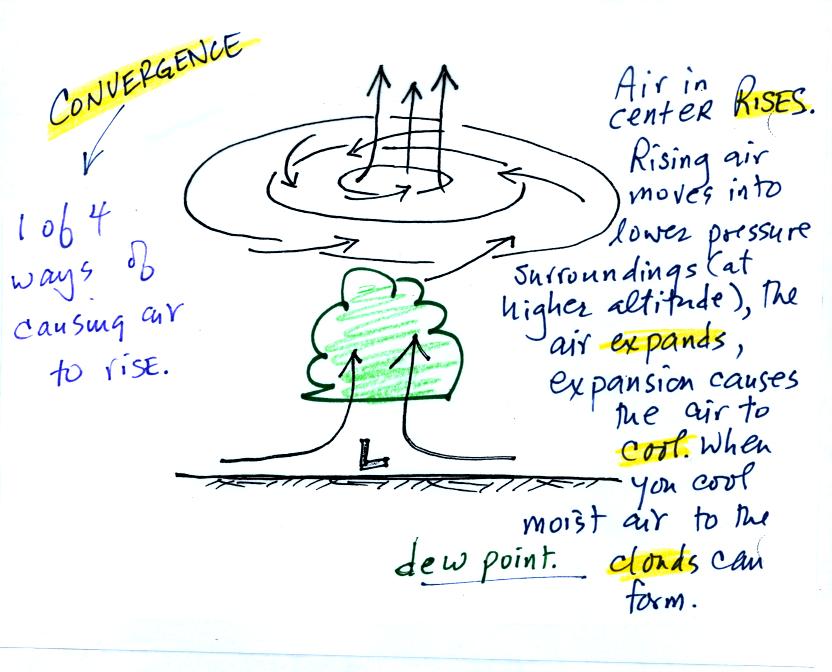

When the converging air reaches the center of the low it starts to rise. Rising air expands (because it is moving into lower pressure surroundings at higher altitude), the expansion causes it to cool. If the air is moist and it is cooled enough (to or below the dew point temperature) clouds will form and may then begin to rain or snow. Convergence is 1 of 4 ways of causing air to rise (we'll learn what the rest are next week). You often see cloudy skies and stormy weather associated with surface low pressure.

Everything is pretty much the exact opposite in the case of surface high pressure.

Winds spin clockwise (counterclockwise in the southern hemisphere) and spiral outward. The outward motion is called divergence.

Air sinks in the center of surface high pressure to replace the diverging air. The sinking air is compressed and warms. This keeps clouds from forming so clear skies are normally found with high pressure (clear skies but not necessarily warm weather, strong surface high pressure often forms when the air is very cold).

Answer to the station model question: the temperature is 75 F, the dew point is 45 F, haze is being reported (the infinity symbol), winds are from the east at 5 knots (5 MPH), 1/8th of the sky is covered with clouds. the pressure is 1010.0 mb

Answer to the isobar question: 1004 mb isobar

The sea level pressure is shown above and to the right of the center circle. Decoding this data is a little "trickier" because some information is missing. We'll look at this in more detail momentarily.

Pressure change data (how the pressure has changed during the preceding 3 hours) is shown to the right of the center circle. You must remember to add a decimal point. Pressure changes are usually pretty small.

Here are some links to surface weather maps with data plotted using the station model notation: UA Atmos. Sci. Dept. Wx page, National Weather Service Hydrometeorological Prediction Center, American Meteorological Society.

Here's how you can decode the pressure data.

Meteorologists hope to map out small horizontal pressure changes on surface weather maps (that produce wind and storms). Pressure changes much more quickly when moving in a vertical direction. The pressure measurements are all corrected to sea level altitude to remove the effects of altitude. If this were not done large differences in pressure at different cities at different altitudes would completely hide the smaller horizontal changes.

In the example above, a station pressure value of 927.3 mb was measured in Tucson. Since Tucson is about 750 meters above sea level, a 75 mb correction is added to the station pressure (1 mb for every 10 meters of altitude). The sea level pressure estimate for Tucson is 927.3 + 75 = 1002.3 mb. This is also shown on the figure below

Here are some examples of coding

and decoding the pressure data. We tried to cover this in about

the last 5 minutes of class which meant rushing things a little bit ( a

lot actually ). So we'll review this at the start of class next

Monday.

To save room, the leading 9 or 10 on the sea level pressure value and the decimal point are removed before plotting the data on the map. For example the 10 and the . in 1002.3 mb would be removed; 023 would be plotted on the weather map (to the upper right of the center circle). Some additional examples are shown above.

When reading pressure values off a map you must remember to add a 9 or 10 and a decimal point. For example

118 could be either 911.8 or 1011.8 mb. You pick the value that falls between 950.0 mb and 1050.0 mb (so 1011.8 mb would be the correct value, 911.8 mb would be too low).

Another important piece of information on a surface map is the time the observations were collected. Time on a surface map is converted to a universally agreed upon time zone called Universal Time (or Greenwich Mean Time, or Zulu time). That is the time at 0 degrees longitude. There is a 7 hour time zone difference between Tucson (Tucson stays on Mountain Standard Time year round) and Universal Time. You must add 7 hours to the time in Tucson to obtain Universal Time.

to convert from MST (Mountain Standard Time) to UT (Universal Time)

2:45 pm MST:

first convert 2:45 pm to the 24

hour clock format 2:45 + 12:00 = 14:45 MST

then add the 7 hour time zone correction ---> 14:45 + 7:00 = 21:45 UT (9:45 pm in Greenwich)

then add the 7 hour time zone correction ---> 14:45 + 7:00 = 21:45 UT (9:45 pm in Greenwich)

9:05 am MST:

add the 7 hour time zone

correction ---> 9:05 + 7:00 = 16:05 UT (4:05 pm in England)

to convert from UT to MST

18Z:

subtract the 7 hour time

zone

correction ---> 18:00 - 7:00 = 11:00 am MST

02Z:

if we subtract the 7 hour time zone correction we will get a negative number.

We will add 24:00 to 02:00 UT then subtract 7 hours

02:00 + 24:00 = 26:00

26:00 - 7:00 = 19:00 MST on the previous day

2 hours past midnight in Greenwich is 7 pm the previous day in Tucson

A bunch of weather data has been

plotted (using the station model notation) on a surface weather map in

the figure

below (p. 38 in the ClassNotes).

Plotting the surface weather data on a map is just the beginning. For example you really can't tell what is causing the cloudy weather with rain (the dot symbols are rain) and drizzle (the comma symbols) in the NE portion of the map above or the rain shower along the Gulf Coast. Some additional analysis is needed. A meteorologist would usually begin by drawing some contour lines of pressure to map out the large scale pressure pattern. We will look first at contour lines of temperature, they are a little easier to understand (easier to decode the plotted data and temperature varies across the country in a fairly predictable way).

Isotherms, temperature contour lines, are usually drawn at 10 F intervals. They do two things: (1) connect points on the map that all have the same temperature, and (2) separate regions that are warmer than a particular temperature from regions that are colder. The 40o F isotherm highlighted in yellow above passes through a city which is reporting a temperature of exactly 40o. Mostly it goes between pairs of cities: one with a temperature warmer than 40o and the other colder than 40o. Temperatures generally decrease with increasing latitude: warmest temperatures are usually in the south, colder temperatures in the north.

Now the same data with isobars drawn in. Again they separate regions with pressure higher than a particular value from regions with pressures lower than that value. Isobars are generally drawn at 4 mb intervals. Isobars also connect points on the map with the same pressure. The 1008 mb isobar (highlighted in yellow) passes through a city at Point A where the pressure is exactly 1008.0 mb. Most of the time the isobar will pass between two cities. The 1008 mb isobar passes between cities with pressures of 1009.7 mb at Point B and 1006.8 mb at Point C. You would expect to find 1008 mb somewhere in between those two cites, that is where the 1008 mb isobar goes.

The pattern on this map is very different from the pattern of isotherms. On this map the main features are the circular low and high pressure centers.

Just locating closed centers of high and low pressure will already tell you a lot about the weather that is occurring in their vicinity.

1.

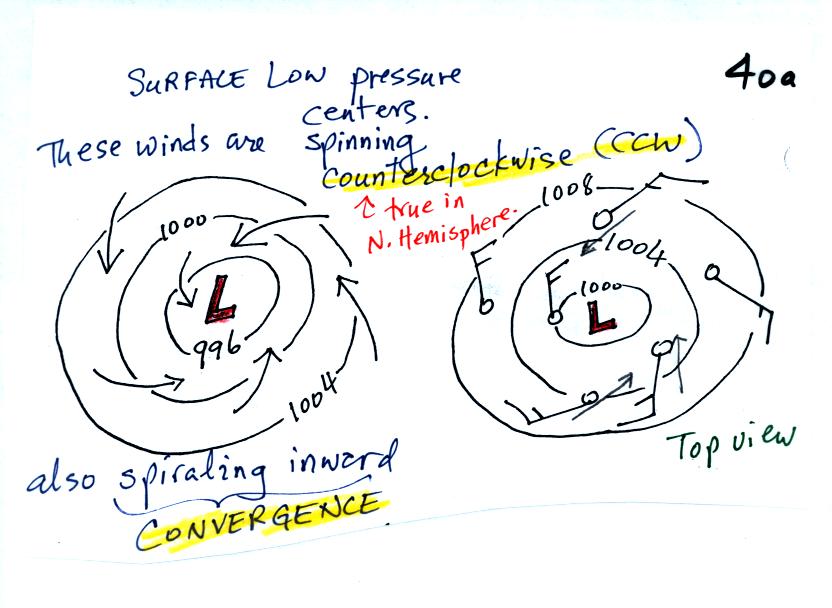

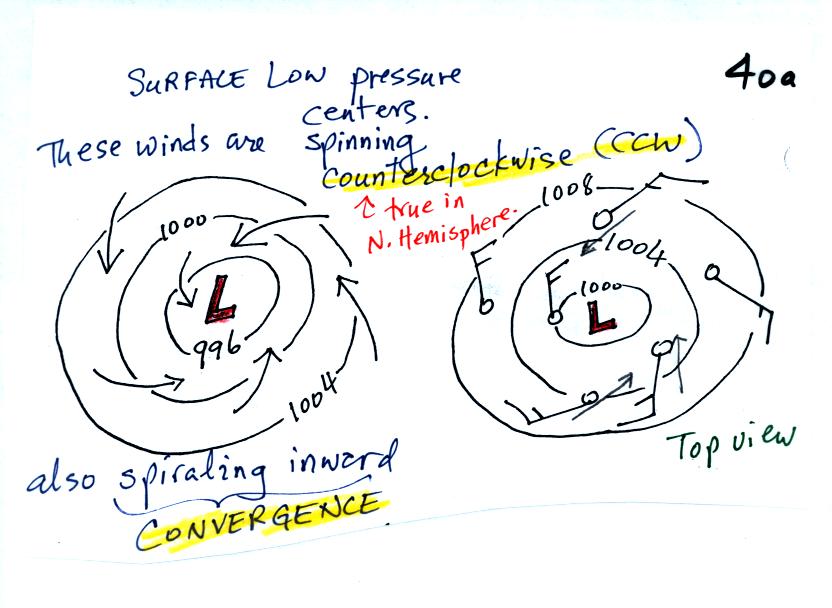

We'll start with the large nearly circular centers of High and Low pressure. Low pressure is drawn below. These figures are more neatly drawn versions of what we did in class.

Air will start moving

toward low

pressure (like a rock sitting on a hillside that starts to roll

downhill), then something called the Coriolis force will cause

the

wind to start to spin (we'll learn more about the Coriolis force later

in the semester). In the northern hemisphere winds spin in a

counterclockwise (CCW) direction

around surface

low pressure

centers. The winds also spiral inward toward the center of the

low, this is called convergence. [winds spin clockwise around low

pressure centers in the southern hemisphere but still spiral inward,

don't worry about the southern hemisphere until later in the semester]

When the converging air reaches the center of the low it starts to rise. Rising air expands (because it is moving into lower pressure surroundings at higher altitude), the expansion causes it to cool. If the air is moist and it is cooled enough (to or below the dew point temperature) clouds will form and may then begin to rain or snow. Convergence is 1 of 4 ways of causing air to rise (we'll learn what the rest are next week). You often see cloudy skies and stormy weather associated with surface low pressure.

Everything is pretty much the exact opposite in the case of surface high pressure.

Winds spin clockwise (counterclockwise in the southern hemisphere) and spiral outward. The outward motion is called divergence.

Air sinks in the center of surface high pressure to replace the diverging air. The sinking air is compressed and warms. This keeps clouds from forming so clear skies are normally found with high pressure (clear skies but not necessarily warm weather, strong surface high pressure often forms when the air is very cold).

Answer to the station model question: the temperature is 75 F, the dew point is 45 F, haze is being reported (the infinity symbol), winds are from the east at 5 knots (5 MPH), 1/8th of the sky is covered with clouds. the pressure is 1010.0 mb

Answer to the isobar question: 1004 mb isobar