Tuesday Aug. 28, 2012

click here to

download today's notes in a more printer friendly format

Arrived in class a little early (after having gone to vote in

today's primary election) with lots of demonstration materials, a few

extra sets of Expt. #1 materials, and 3 songs from Brandi Carlile ("That Year", "I Will", and "Touching the Ground").

The 1st of the 1S1P

Assignments

was announced in class today. You can do 0,1, or 2

reports. What

you should be trying to do is earn 45 1S1P pts by the end of the

semester. There will be future assignments, so you don't have to

do any reports this time. But I would suggest you write at least

one report just so you can get a feel for how the reports are graded.

All of the names on the various experiment signup sheets should now be

online. You can check by clicking on the Report Signup Lists link.

We started by looking quickly at some information that was stuck

onto the end of the Thursday Aug. 23 notes

concerning some of the causes of death both in the US and around the

world. This was just to get an idea of how serious a threat air

pollution is.

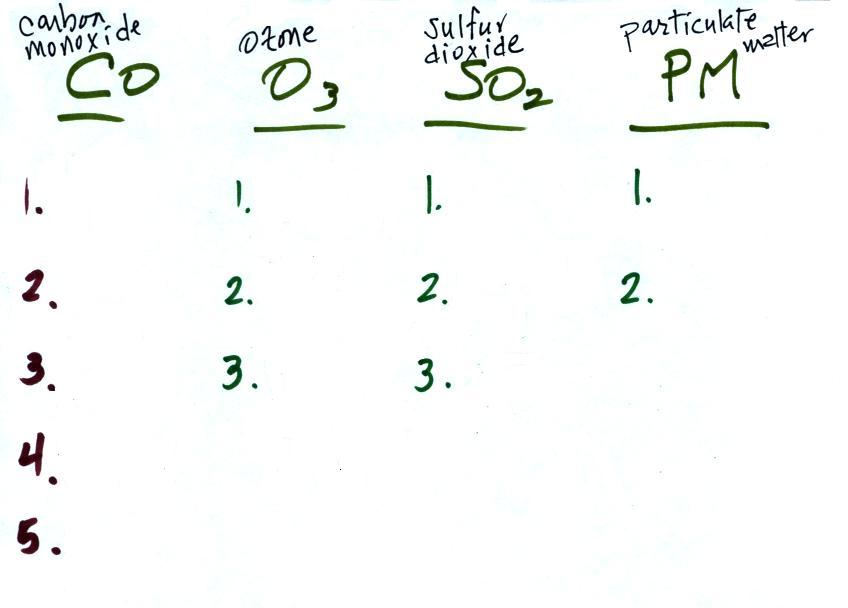

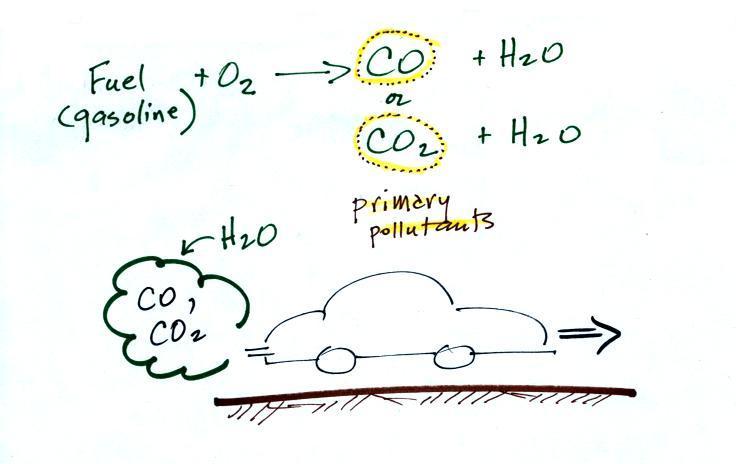

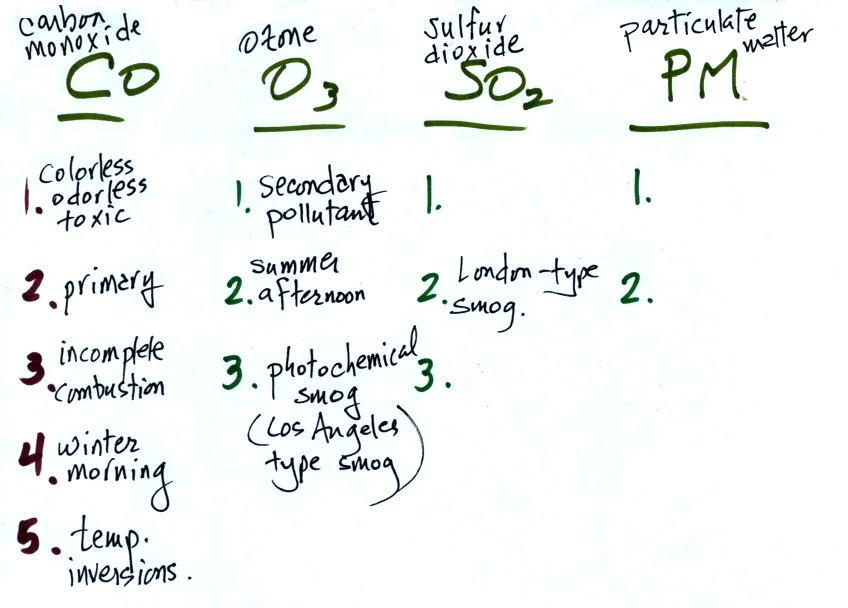

Today and on Thursday we'll be looking at four main air

pollutants, carbon monoxide, ozone, sulfur dioxide, and

particulate matter. They all have a unique "personality".

One way of distinquishing between these pollutants is make a table and

to list the main characteristics or properties of each pollutant.

We'll cover carbon monoxide and ozone today and you'll find this

same chart at the end of today's notes with the 1st two columns filled

in.

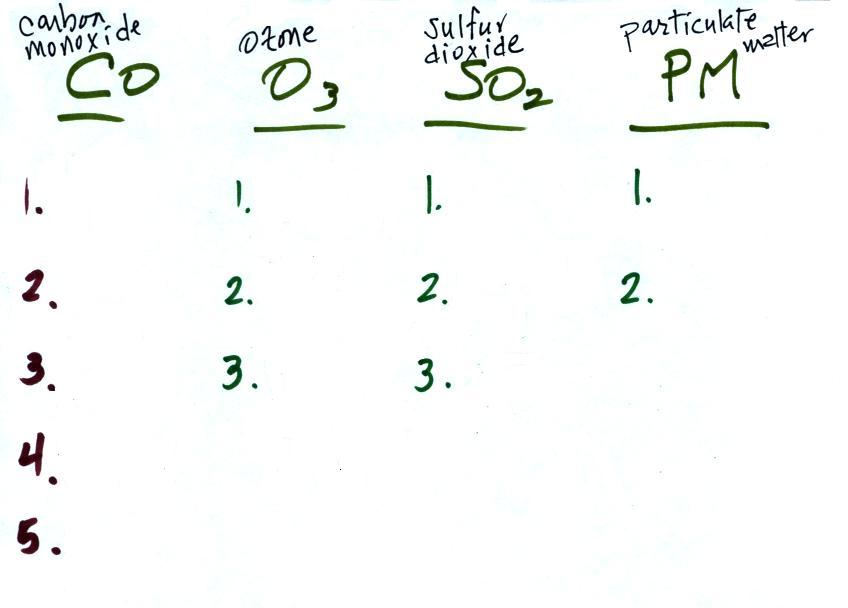

You've probably heard about carbon monoxide, we'll start with

that. You'll

find

additional

information

on

carbon

monoxide and other air pollutants at

the Pima

County Department of

Environmental Quality website and also at the US Environmental

Protection Agency

website.

We will mostly be talking about

carbon

monoxide found outdoors, where it would rarely reach fatal

concentrations. CO is a serious hazard indoors also where it

can (and does) build up to deadly concentrations. (several

people

were

almost

killed

in

Tucson

in

December 2010)

Carbon monoxide is insidious, you can't smell it or see it

and it can kill you (Point 1).

Once

inhaled,

carbon

monoxide

molecules

bond

strongly

to

the

hemoglobin

molecules

in

blood

and

interfere

with

the

transport

of

oxygen

throughout

your

body.

The

article

above

mentions

that

the

CO

poisoning

victims

were

put inside a hyperbaric (high pressure) chamber filled with pure

oxygen. This must force oxygen into the blood and displace the

carbon monoxide.

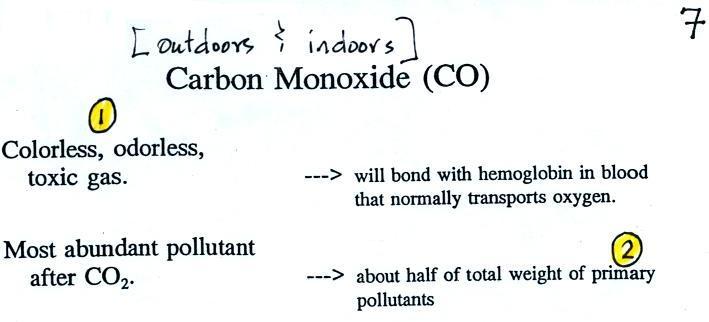

CO is a primary pollutant (Point 2

above). That means it goes

directly from a source into the air, CO is

emitted directly from an automobile tailpipe into the atmosphere for

example. The difference between

primary and secondary pollutants is probably explained

best in a series of pictures.

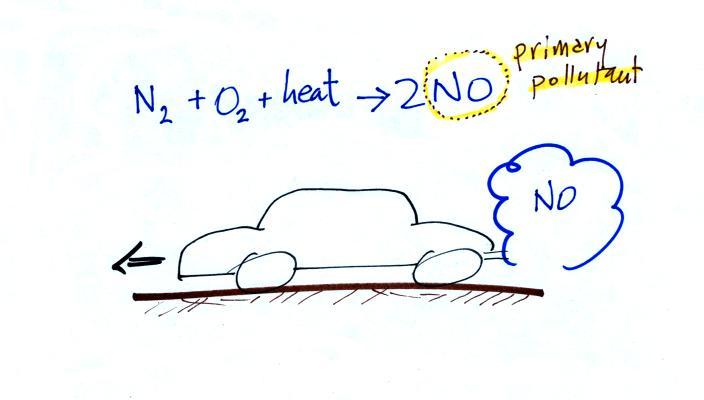

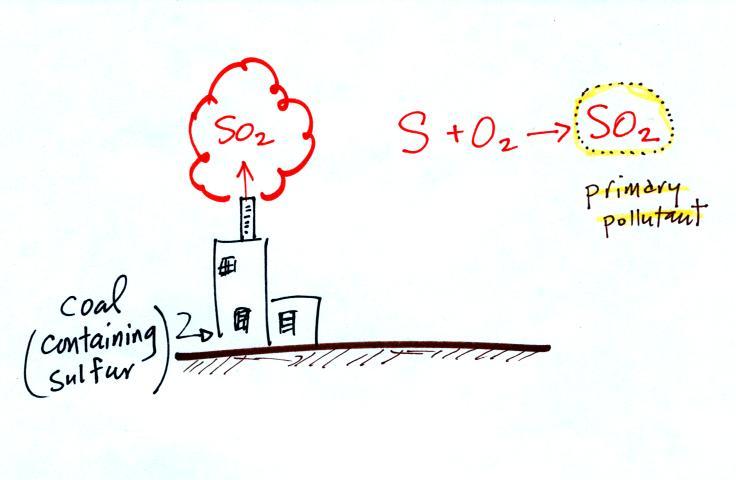

In addition to carbon monoxide, nitric oxide

(NO) and sulfur

dioxide (SO2), are also primary

pollutants. They all go

directly from a source (automobile tailpipe or factory chimney) into

the atmosphere. Ozone is a

secondary pollutant (and here we are referring to tropospheric ozone,

not stratospheric ozone). It doesn't come directly from an

automobile tailpipe. It shows up in the atmosphere only

after a

primary pollutant has undergone a series of reactions.

Point 3

explains that CO is produced by incomplete

combustion of fossil

fuel (insufficient oxygen). Complete combustion would produce

carbon dioxide,

CO2. Cars and trucks

produce much of the CO in

the

atmosphere in Tucson.

Vehicles must now

be fitted with a catalytic

converter that will change CO into CO2

(and also NO into N2

and

O2

and hydrocarbons into H2O

and CO2).

In

Pima

County

vehicles

must

also

pass

an

emissions

test

every

year

and

special

formulations

of

gasoline

(oxygenated fuels) are used

during the winter months to try to reduce CO emissions.

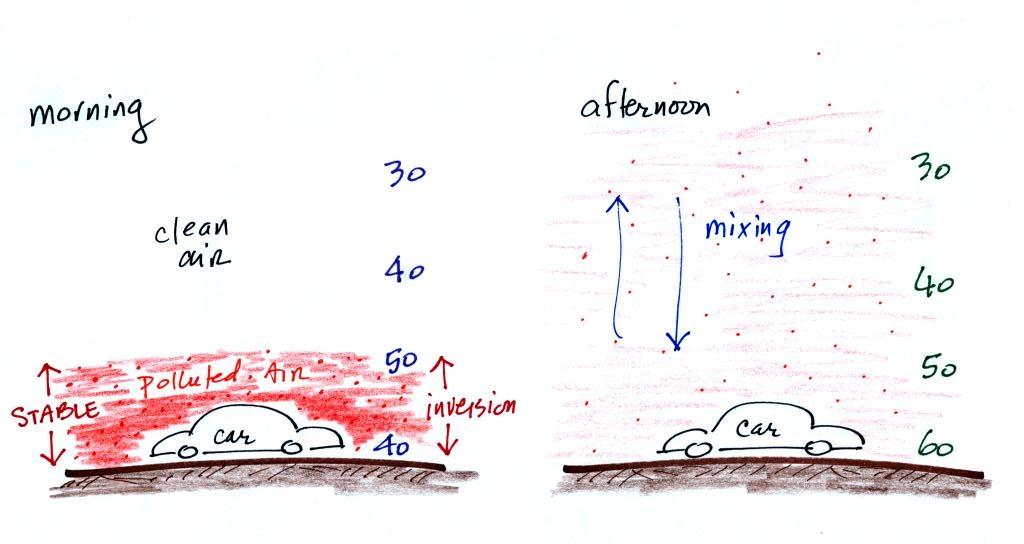

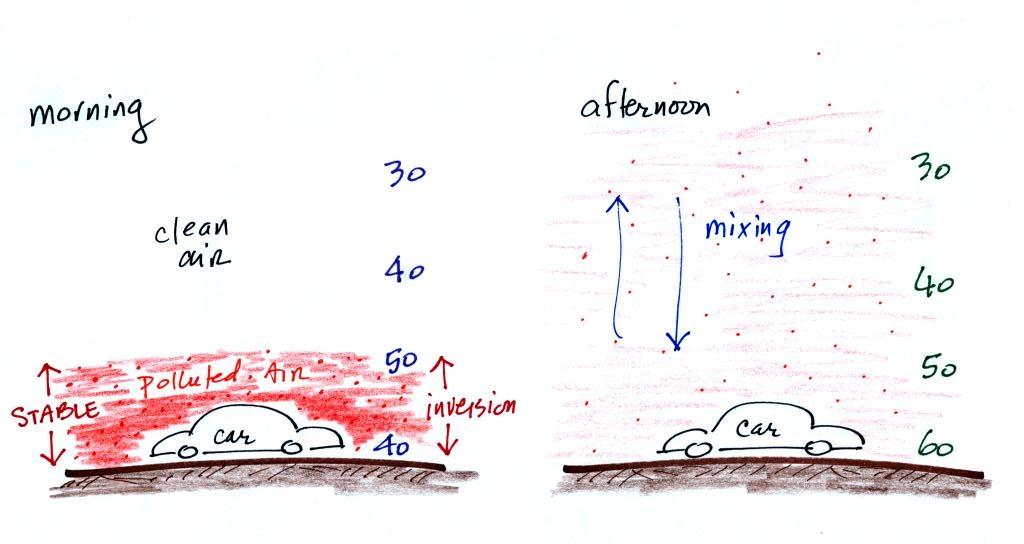

In the atmosphere CO concentrations peak on winter

mornings (Point 4). The

reason for this is surface radiation inversion layers. They are

most likely to form on cold winter mornings.

In an inversion layer (Point 5)

air temperature

actually increases with increasing altitude which is just the opposite

of what we are used to. This produces stable atmospheric

conditions which means there is little up or down air motion. Air

at the surface can't mix with cleaner air above.

By afternoon the ground and air in contact with the ground has

warmed. Temperature decreases with increasing altitude above the

ground, the inverison layer is gone. Pollutants are emitted into

a much larger volume of air and the concentration doesn't get as high.

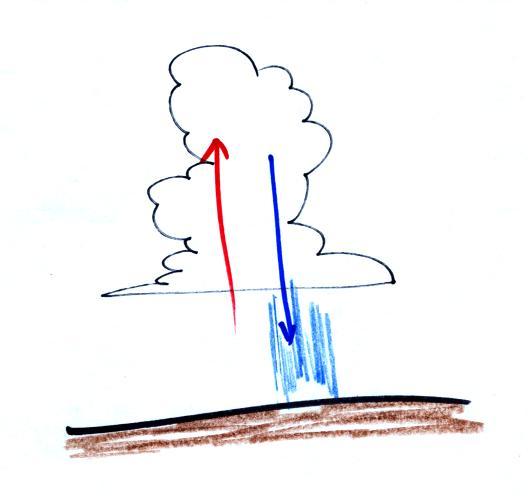

Thunderstorms

contain strong up

(updraft) and down (downdraft) air motions. Thunderstorms are a

sure indication of unstable

atmospheric conditions.

We have a little more information to cover about carbon monoxide

but we'll postpone it until Thursday.

You are able to see a lot of things

in the atmosphere (clouds,

fog, haze, even the blue sky) because of scattering of light. I'm

going to try to make a cloud of smog in class later todeay.

The

individual droplets making up the smog cloud are too small to be seen

by

the

naked eye. But you will be able to see that they're there because

the droplets scatter light. So we took some time for a

demonstration that tried to show you

exactly what light scattering is.

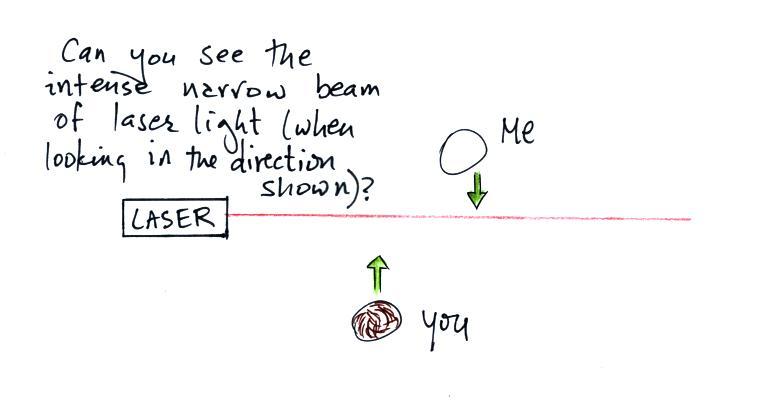

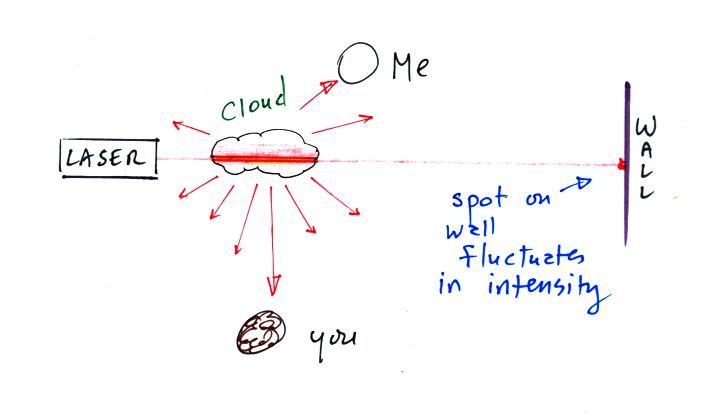

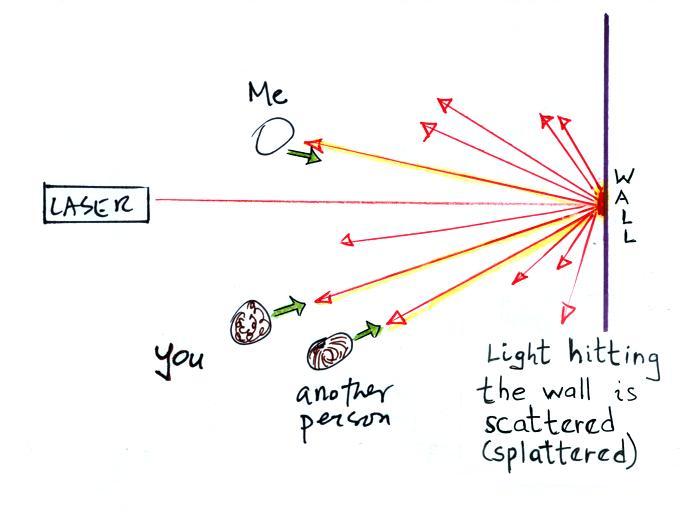

In the first part of the demonstration a narrow beam of intense

red

laser light was directed from the middle of the classroom toward the

wall

Looking down on the situation in

the figure above. Neither

the students or the instructor could see the beam of light.

To be able to see something rays of light must travel from the object

straight toward you. Nobody could see the beam because there

weren't any rays of light

pointing from the laser beam toward the students or toward the

instructor.

The instructor would have been

able

to see the beam if he had stood at the end of the beam of laser light

and looked back along the beam of light toward the laser. That

wouldn't have been a smart thing to do, though, because the beam was

strong

enough to possibly damage his eyes (there's a warning on the

side of the laser).

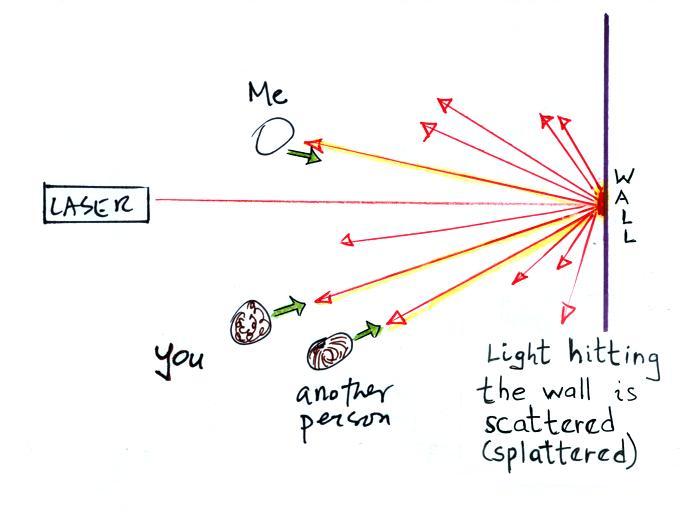

Everybody was able to see a bright red spot where the laser beam

struck

the wall.

This is because when the intense

beam of

laser light

hits the wall it

is scattered (splattered is a

more descriptive term). The original beam is broken up into a

myriad of weaker rays

of light that are sent out in all directions. There is a ray of

light

sent in the direction of every student in the class. They see the

light because they are looking back in the direction the ray came

from. It is safe to look at this light because the original

intense beam is split up into many much weaker beams.

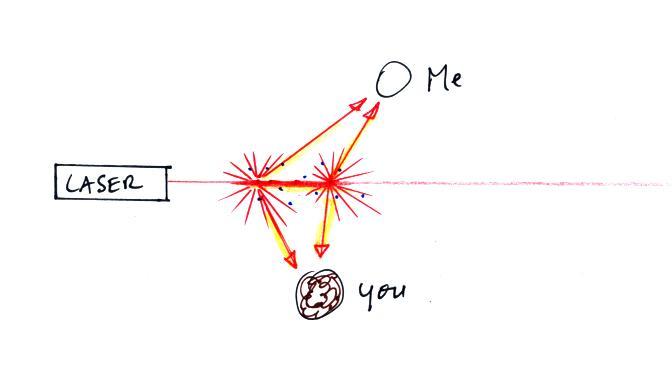

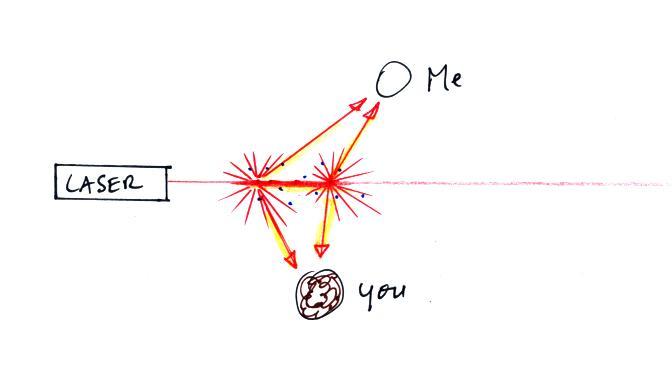

Next we clapped some erasers together so that some small

particles of chalk dust fell into the laser beam.

Now instead

of a single spot on the wall, students

saws lots of

points of light coming from different positions along a straight

segment of the laser

beam. Each of these points of light was a particle of chalk, and

each piece of chalk dust was intercepting laser light and sending light

out in all directions. Each student saw a ray of light coming

from

each of the chalk particles.

We use chalk because it is white, it will scatter rather

than absorb visible light. What would you have seen if black

particles

of soot had been dropped into the laser beam?

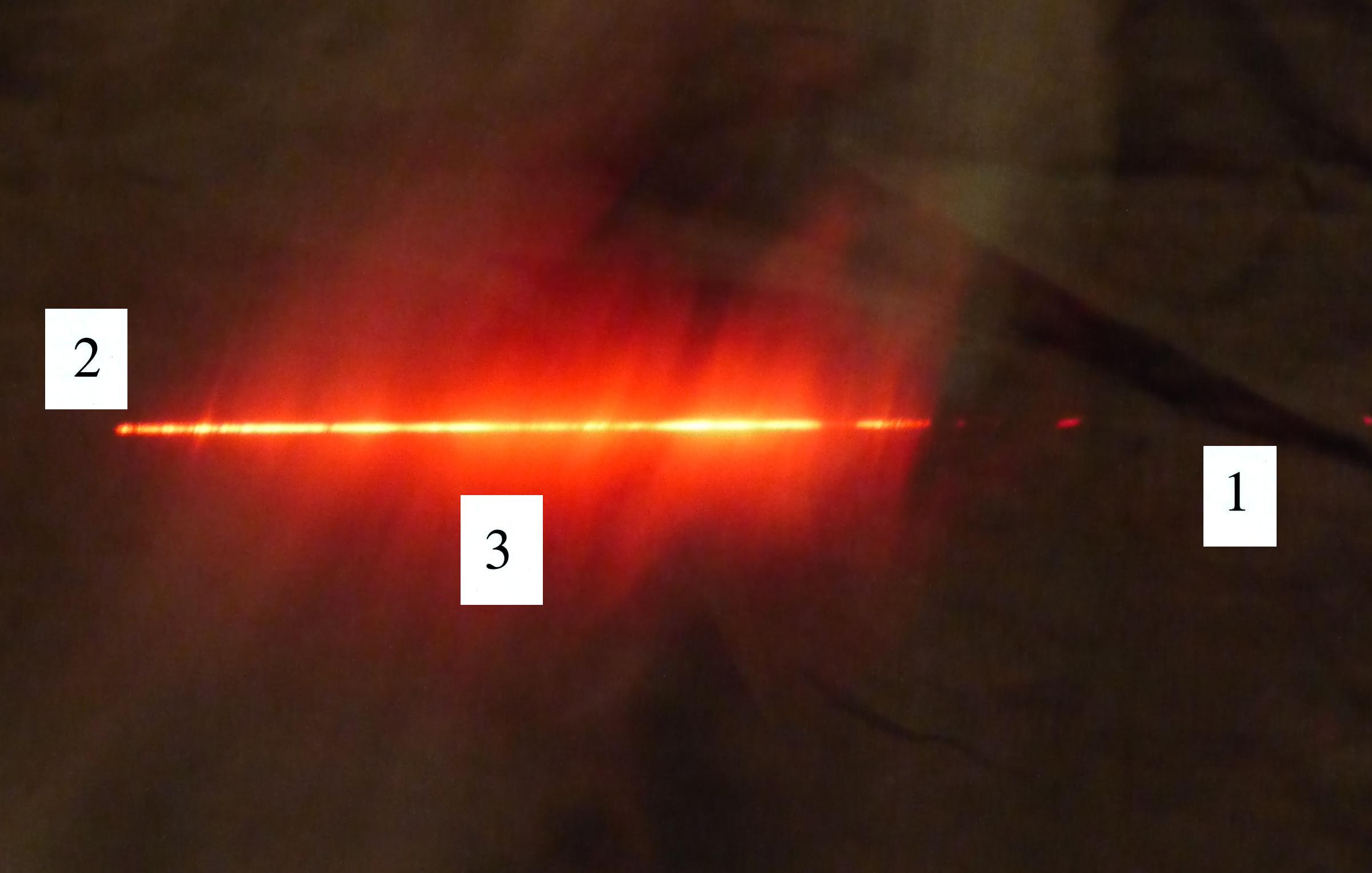

In the last part of the demonstration we made a cloud by

pouring some

liquid nitrogen into a cup of water. The cloud droplets are much

smaller than the chalk particles but are much more numerous. They

make very good scatterers.

The beam of laser

light really lit up as it passed through the small patches of

cloud. The cloud droplets are small but there are many of

them. So

much light was scattered

that the spot on the wall fluctuated in intensity (the spot dimmed when

lots of

light was being scattered, and brightened when not as much light was

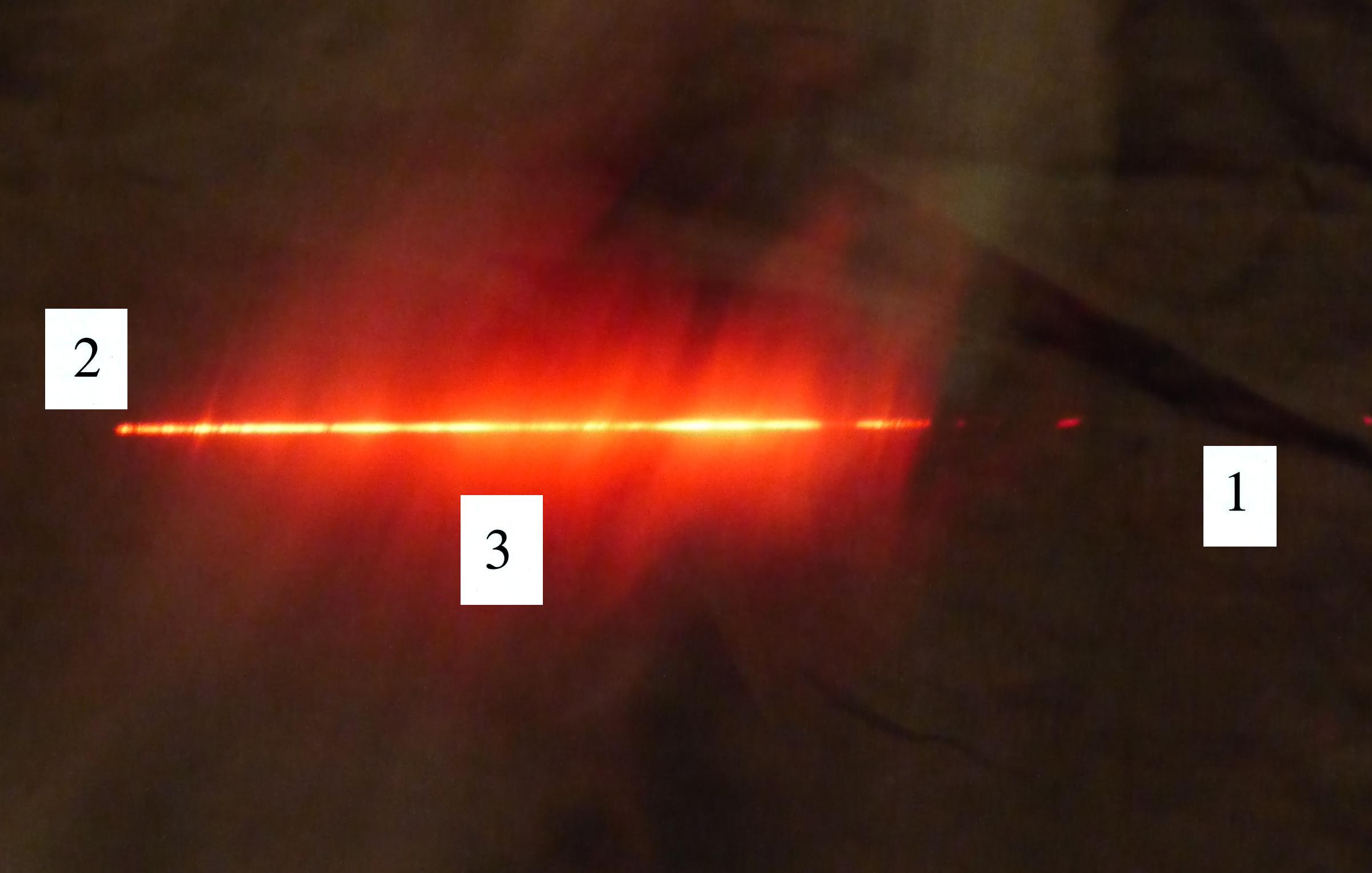

scattered). Here's a photo I took back in my office.

The laser beam is visible in the

left 2/3 rds of the picture

because it is passing through cloud and light is being scattered toward

the camera. There wasn't any cloud on the right 1/3rd of the

picture so you can't see the laser beam over near Point 1.

There's something else going on in this picture also. We're

not just seeing the narrow beam of laser light but some of the cloud

outside the laser beam is also visible.

Up to this point we've just considered single scattering. A

beam

of light encounters a cloud droplet or a particle of chalk and gets

redirected and then travels all the way to your eye or to a

camera. That's what's happening at Point 2. You just see

the narrow laser beam. But sometimes the scattered ray of light

runs into

something else and gets scattered again. This is called multiple

scattering. And that is what is illuminating the cloud alongside

the beam of laser light at Point 3. Light is first scattered by a

cloud droplet in the beam. As it leaves the beam it runs into

another droplet and gets scattered again. So now it looks like it

is coming from the cloud surrounding the laser beam rather than from

the beam itself.

Sunlight is

white light which means it's made up of a mixture of violet, blue,

green, yellow, orange, and red

light. Air molecules have an unusual property: they scatter the

shorter wavelengths (violet, blue, green) much more readily than the

longer wavelength colors in sunlight (yellow, orange, and red).

When you look away from the sun and look at the sky, the blue color

that you see are the shorter wavelengths in sunlight that are being

scattered by air molecules.

You shouldn't look directly at the sun. Direct sunlight is

too intense just as was true with the laser. But it is OK to look

at the blue sky. That's scattered sunlight and is much weaker

than direct sunlight and safe to look at.

We'll come back to

this concept of scattering of light in the next couple of lectures.

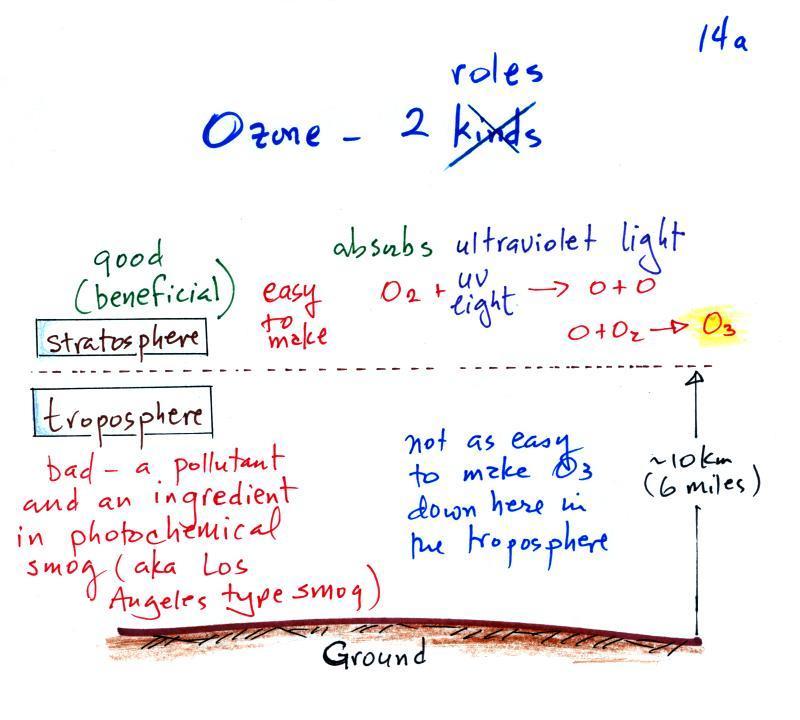

Now back to air pollutants - ozone.

Ozone has a kind of Dr.

Jekyll

and

Mr

Hyde personality.

The figure above can be found on p.

14a in the photocopied ClassNotes. The ozone layer (ozone

in

the stratosphere) is beneficial, it absorbs dangerous

high

energy ultraviolet light (which would otherwise reach the ground and

cause skin cancer, cataracts, etc. There are some types of UV

light that would quite simply kill us).

Ozone in the troposphere is bad, it is toxic and a

pollutant. Tropospheric

ozone is also a key component of photochemical smog (also known as Los

Angeles-type smog)

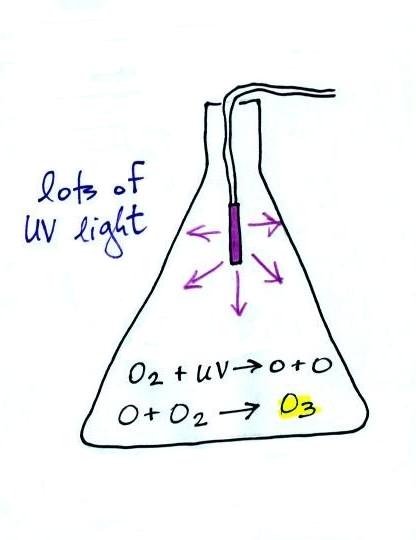

We'll be making some photochemical smog in a

class

demonstration. To do this we'll first need some ozone; we'll make

use of the simple stratospheric recipe (shown above) for making what we

need instead of the more complex tropospheric

process (the 4-step process in the figure below). You'll find

more details a little further down in the notes.

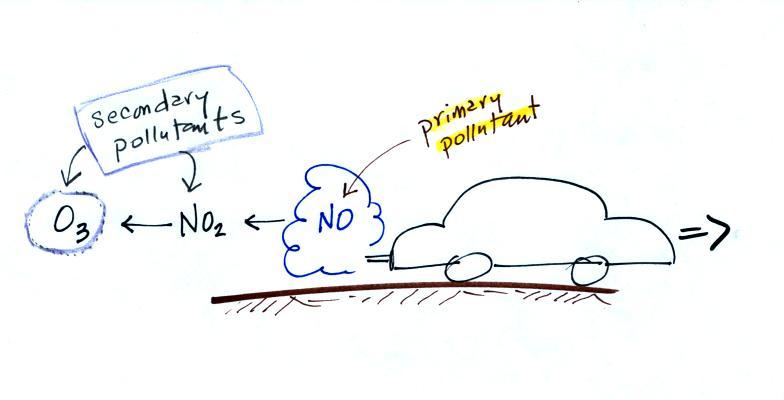

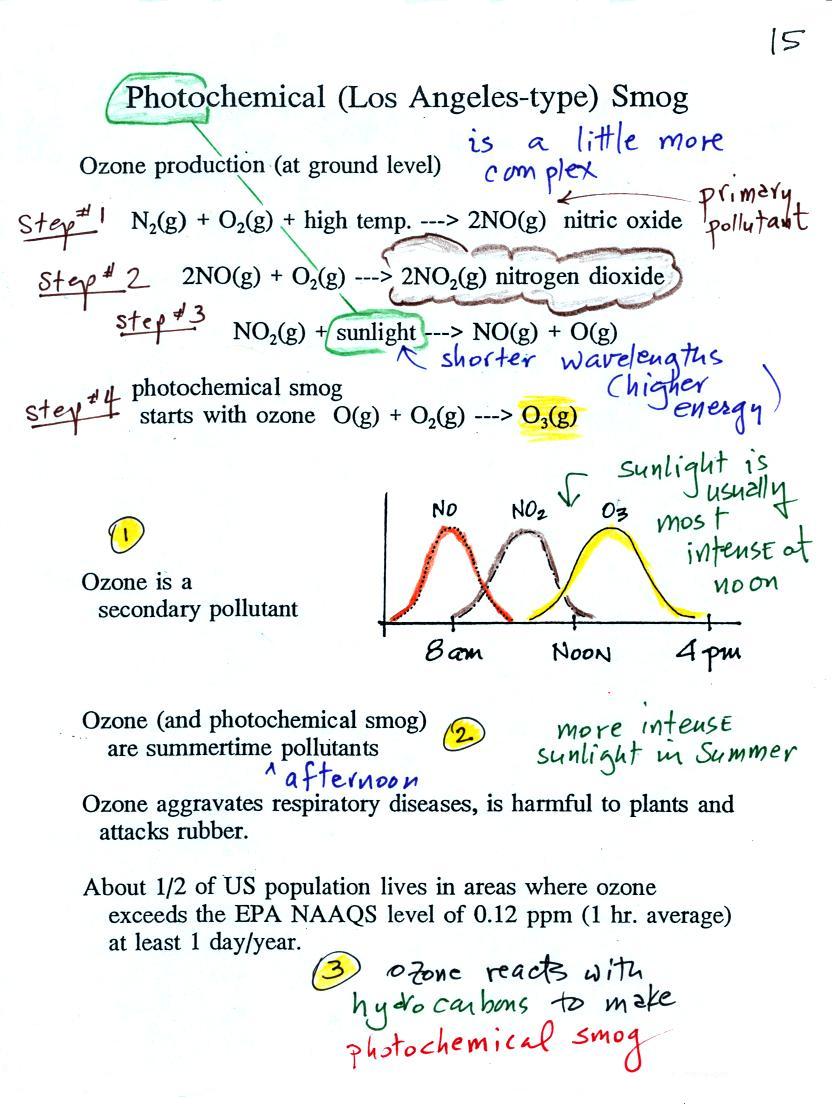

At the top of this figure (p. 15 in the packet of

ClassNotes) you see

that a more complex

series

of

reactions is responsible for the production of tropospheric

ozone. The production of tropospheric

ozone begins with nitric

oxide

(NO). NO is produced when nitrogen and oxygen in air are heated

(in an

automobile engine for example) and react. The NO can then react

with oxygen in the air to make nitrogen dioxide, the poisonous

brown-colored

gas that I've been thinking about making in class. Sunlight

can

dissociate

(split)

the nitrogen dioxide

molecule producing atomic oxygen (O) and NO. O and O2

react in a 4th step to make ozone (O3) just like happens in the

stratosphere.

Because ozone

does not come directly from an automobile tailpipe or factory chimney,

but only shows up after a series of reactions in the air, it is a

secondary

pollutant. Nitric oxide (NO) would be the primary pollutant

in

this example.

NO is produced early in the day (during the morning rush

hour).

The concentration of NO2

peaks

somewhat later. Because sunlight is needed in step #3 and because

sunlight is usually most intense at noon, the

highest ozone concentrations are usually found in

the afternoon. Ozone concentrations are also usually higher in

the summer when the sunlight is most intense.

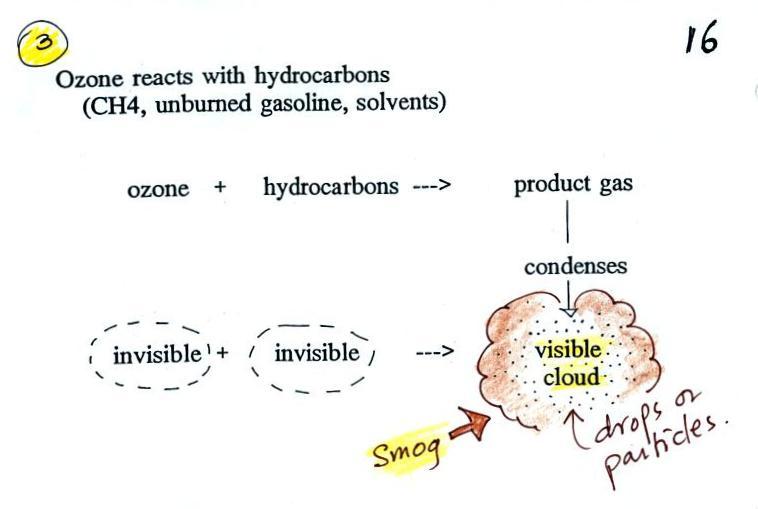

Once ozone is formed, the ozone can react with a hydrocarbon of

some

kind to make a

product

gas. The ozone, hydrocarbon, and product gas are all invisible,

but the product gas sometimes condenses to make a visible smog

cloud or haze. The cloud is composed of very small droplets or

solid particles. They're too small to be seen but they are able

to scatter light - that's why you can see the cloud.

Here's a pictorial summary of the photochemical smog demonstration.

We started by putting a small "mercury vapor" lamp inside a

flash. The bulb produces a lot of ultraviolet light (the bulb

produced a dim bluish light that we could see, but the UV light is

invisible

so we had no way of really telling how bright it was). The UV

light and oxygen in the air produced a lot of ozone (you could easily

have smelled it if you had taken the cover off the flask).

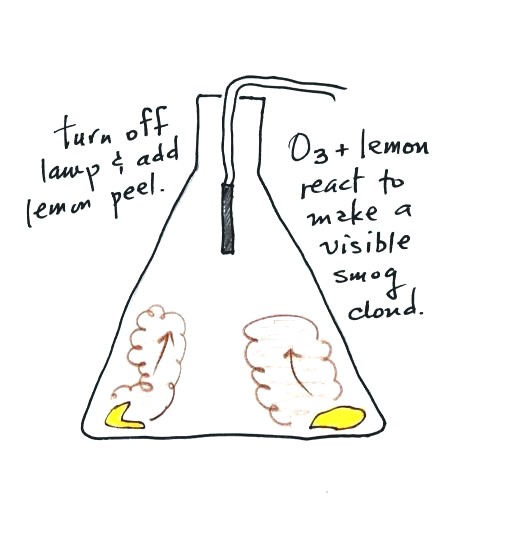

After a few minutes we turned off

the lamp and put

a few pieces of lemon peel into the flash. Part of the smell that

comes from lemon peel is limonene, a hydrocarbon. The limonene

gas reacted with the ozone to produce a product gas of some kind.

The product

gas

condensed, producing a visible smog cloud (the cloud was white, not

brown as shown above). I meant (but forgot) to shine the

laser beam

through the

smog cloud to reinforce the idea that we are seeing the cloud because

the drops or particles scatter light.

Here are the main points that we covered so far, for carbon

monoxide (CO) and ozone. We'll cover sulfur dioxide and

particulate matter later in the week and finish the table.