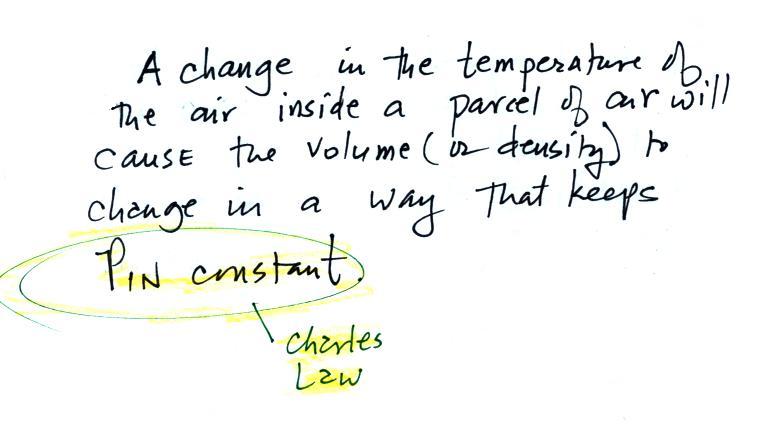

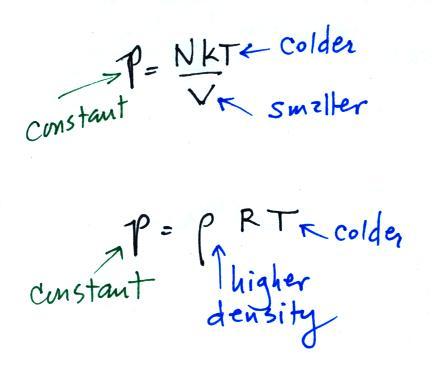

In Charles Law we assume that the

pressure of a parcel of air will remain constant (parcel is just

another word for volume). Changing the temperature of a volume of

air will cause a change in density and volume and pressure will stay

constant. This is an important situation because this is how

volumes of air in the atmosphere behave.

The explanation

below is a little more detailed and more carefully illustrated version

of what was done in class.

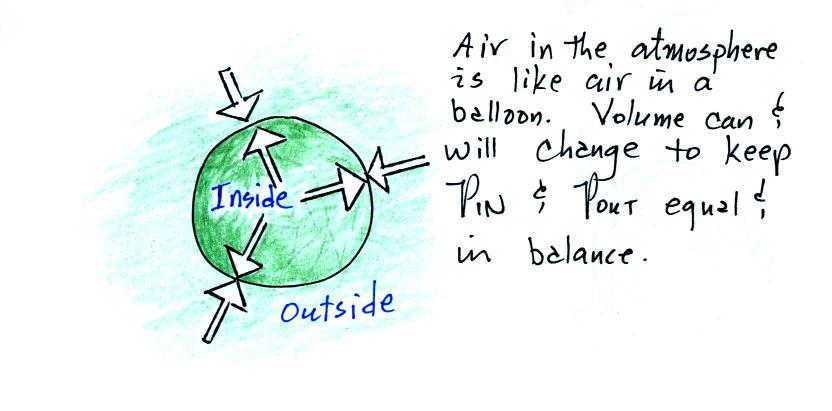

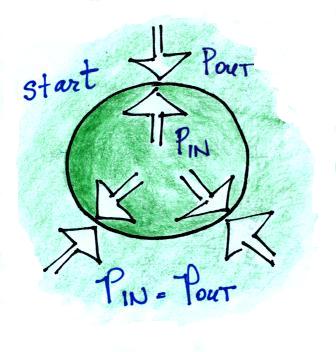

We start with a balloon of air. The air inside and outside

the balloon (or parcel) are exactly the same.

Note the pressure pushing inward is balanced by the pressure of the air

inside the balloon that is pushing outward. If we change

something inside the balloon that upsets this pressure balance, the

balloon would expand or shrink until the pressures were again in

balance.

Volumes of air in the atmosphere will always try to keep the

pressure of the air inside the parcel constant (P

inside is always trying to stay equal to P outside). That's why

we say air in the atmosphere obeys Charles' Law.

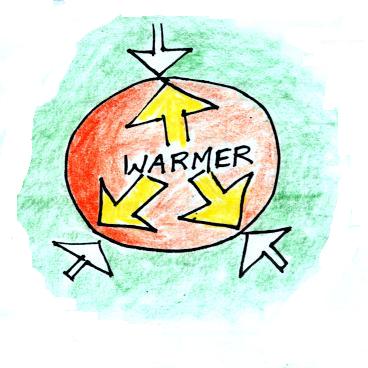

First let's imagine warming the air inside a balloon. We'll won't

change the temperature of the air outside the balloon.

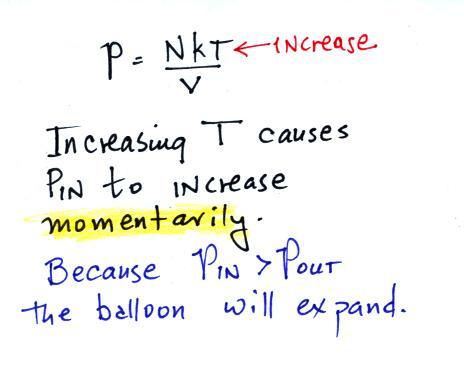

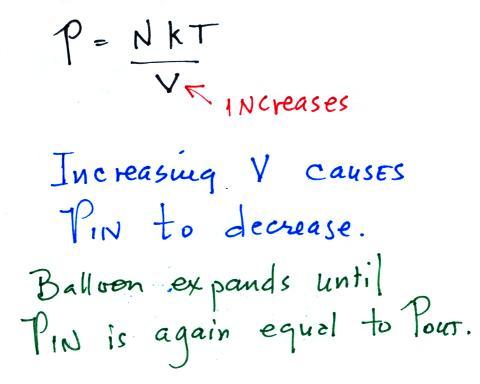

Increasing the temperature will momentarily increase the

pressure. This creates an imbalance. Now that P inside is

greater than P outside the

balloon will expand.

Increasing the volume causes the pressure to start to decrease.

The balloon will keep expanding until P inside is back in balance

with P outside.

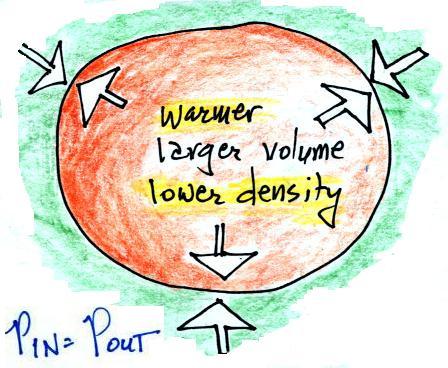

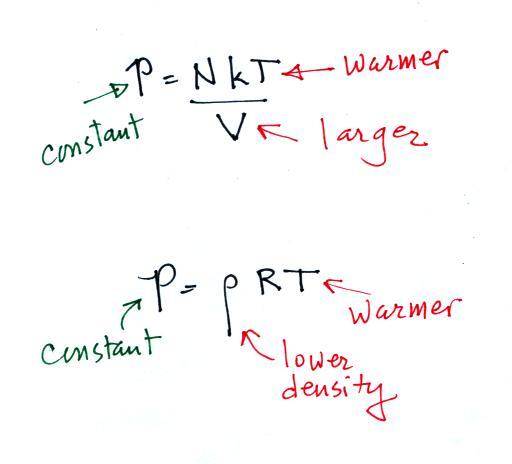

We're left with a balloon that is larger, warmer, and filled with lower

density air than it was originally.

The pressures inside and outside are again the same. The pressure

inside is back to what it was before we warmed the air in the

balloon. You can increase the temperature and volume

of a parcel together in a way that keeps pressure constant (which is

what Charles' law requires). Or you can increase the temperature

and decrease the density together and keep the pressure constant.l

We can go through the same kind of reasoning and see what happens

if we cool the air in a parcel. I've included all the steps

below; that wasn't done in class.

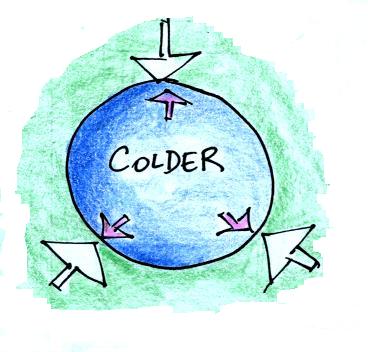

We'll start with a parcel of air that has the same temperature and

density as the air around it.

We'll cool the air inside the parcel. The air outside stays

the same.

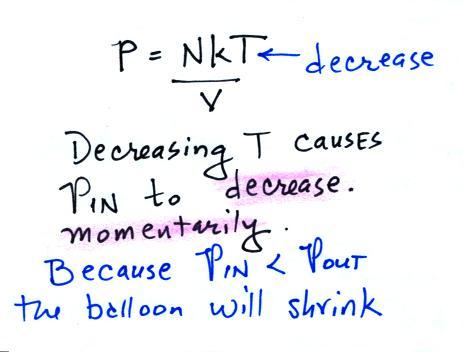

Reducing the air temperature causes the pressure of the air inside

the balloon to decrease. Because the outside air pressure is

greater than the pressure inside the balloon the parcel is compressed.

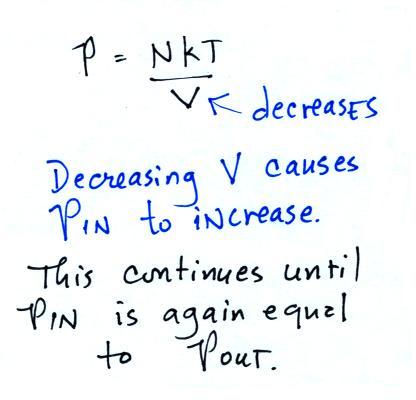

The balloon will get smaller and

smaller (and the pressure inside will get bigger and bigger) until the

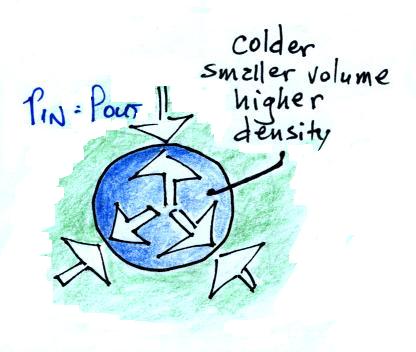

pressures inside and outside the balloon are again equal. The

pressure inside is back to the value it had before you cooled the air

in the parcel.

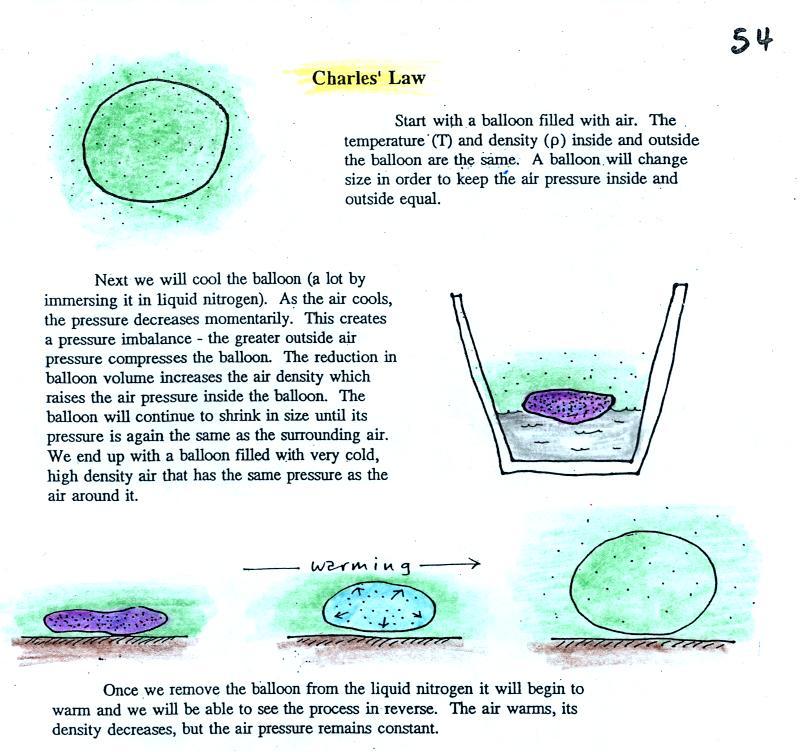

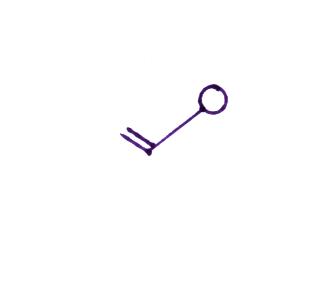

If you want to skip all the details and just remember one thing,

here's what I'd recommend (a statement that I

didn't show in class)

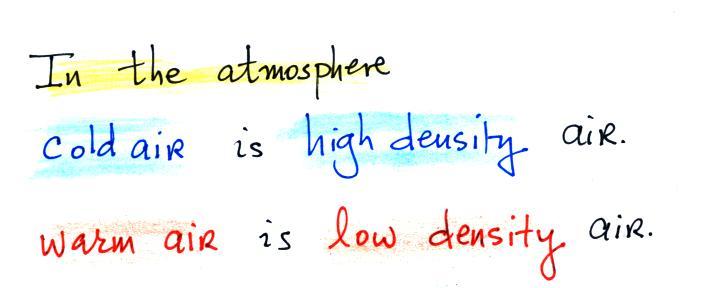

Charles

Law can be demonstrated by dipping a balloon in

liquid

nitrogen. You'll find an explanation on the top of p. 54 in the

photocopied ClassNotes.

The balloon shrinks down to practically nothing when dunked in the

liquid nitrogen. It is filled with very cold, very high density

air. When the balloon is pulled from the liquid nitrogen and

starts to warm up it expands. Density in the balloon

decreases. The volume and temperature keep changing

in a way that kept pressure constant (pressure inside the balloon is

staying equal to the air pressure outside the balloon).

Eventually the balloon ends

up back at room temperature (unless it pops while warming up).

Step #3 Vertical forces acting on parcels of air

And finally the last step toward understanding why warm air rises

and cold air sinks. We'll have a look at the forces that act on

parcels of air in the atmosphere. This information is

found on p. 53

in the photocopied

ClassNotes.

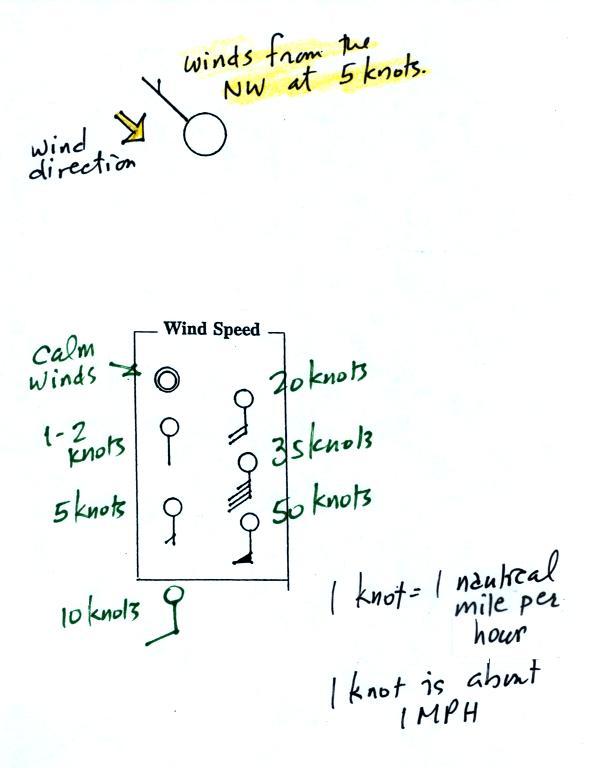

Basically it comes down to this - there are two forces

acting on a parcel of air in

the atmosphere. They are shown on the left hand side

of the figure above.

First is gravity, it pulls downward. The strength of the gravity

force

(the weight of the air in the parcel) depends

on the mass of the air inside

the parcel.

Second there is an upward pointing pressure difference force.

This

force is

caused by the air outside

(surrounding) the parcel. Pressure decreases with increasing

altitude. The pressure of the air at the bottom of a parcel

pushing upward is slightly stronger than the pressure of the air at the

top of the balloon that is pushing downward. The overall effect

is an upward pointing force.

When the air inside a parcel is exactly the same as the air

outside,

the two forces are equal in strength and cancel out. The parcel

is

neutrally bouyant and it wouldn't rise or sink, it would just sit in

place.

Now have a look at the right hand side of the figure.

If you replace the air inside the balloon with warm low density

air, it

won't weigh as much. The gravity force is weaker. The

upward

pressure difference force doesn't change (because it is determined by

the air outside the balloon which hasn't changed) and ends up stronger

than the

gravity force. The balloon will rise.

Conversely if the air inside is cold high density air, it weighs

more. Gravity is stronger than the upward pressure difference

force and the balloon sinks.

It all comes down to how the density of the in parcel compares to

the density of the air surrounding the parcel. If the parcel is

filled with low density air it will rise. A parcel full of high

density air will sink.

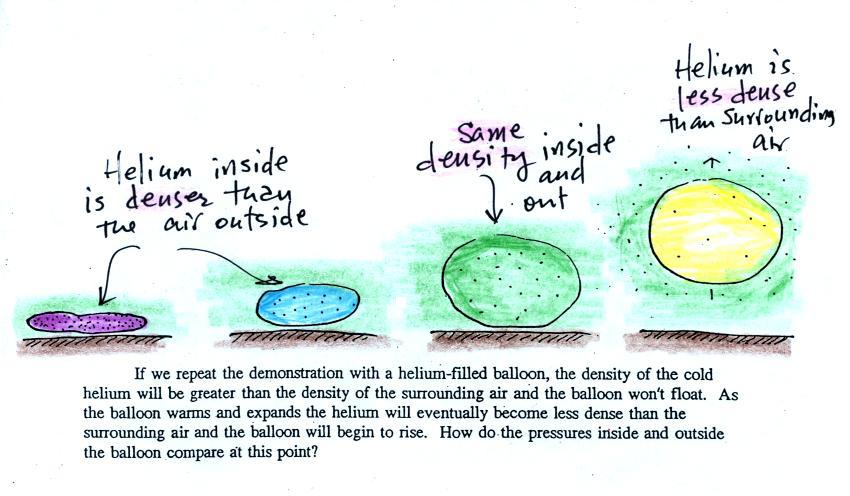

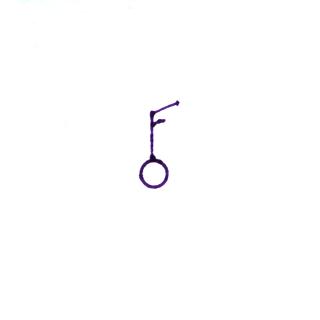

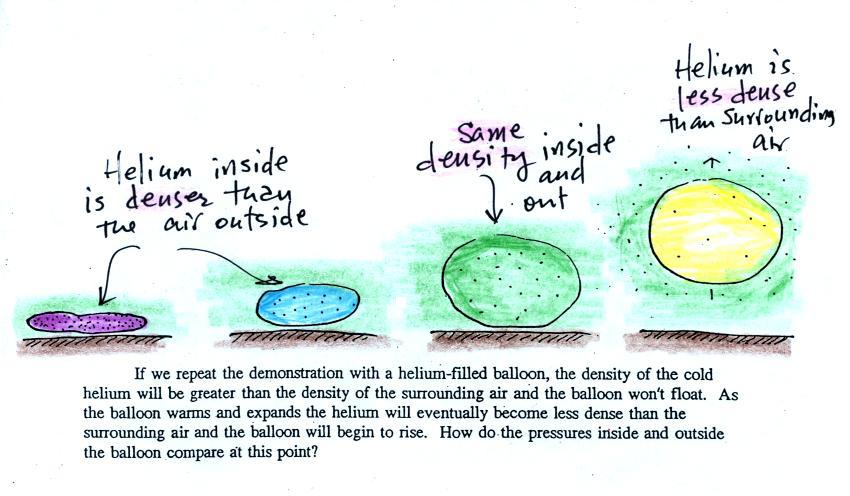

We did a short demonstration to show how density can

determine

whether an object or a parcel of air will rise or sink. We used

balloons filled with helium (see bottom of p. 54 in

the photocopied Class

Notes). Helium is less dense than air even when it has the same

temperature as the surrounding air. A

helium-filled balloon doesn't need to warmed up in order to rise.

We dunked the helium-filled balloon

in some liquid nitrogen to cool

it

and to cause the density of the helium to increase. When

removed

from the liquid nitrogen the balloon didn't rise, the gas inside was

denser than the surrounding air (the purple and blue balloons in the

figure above). As the balloon warms and expands

its density decreases. The balloon at some point has the same

density as the air around it (green above) and is neutrally

bouyant (it's still cooler than the surrounding air). Eventually

the balloon becomes less dense that the

surrounding air (yellow) and floats up to the ceiling (which in ILC 150

is about 30 feet high)

Something like this happens in the

atmosphere.