Tuesday Oct. 17, 2017

La Santa Cecilia "Losing Game"

(3:15), "La

Negra" (3:16), "I Won't Cry

for You" (3:40), "Odiame"

(3:40) and a selection or two

from the first all female mariachi band in New York City Mariachi

Flor de Toloache "Rhythm in

Motion" (3:26), "Dulces

Recuerdos" (3:37)

An In-class

Optional Assignment was handed out in class today. If

you weren't in class and would like to download the assignment,

answer the questions, and turn in the assignment before the quiz

on Thursday you can do so. You will earn at least partial

credit on the assignment.

How much of the sunlight arriving at the top of the

atmosphere actually makes it to the ground?

In the simplified explanation of the greenhouse

effect last week we assumed that 100% of the sunlight arriving

at the top of the earth's atmosphere passed through the

atmosphere and got absorbed at the ground. That would be a

reasonable assumption if sunlight were just visible light, but

it's not. We will now look at how realistic that

assumption is.

The bottom figure above shows that on average (averaged over

the year and over the globe) about half (50%)

of the incoming sunlight makes it through the atmosphere and

gets absorbed at the ground. This is the only number in

the figure you should try to remember.

About 20% of the incoming sunlight is absorbed by gases in the

atmosphere. Sunlight is a mixture of mostly visible and near

IR light. There are smaller amounts of far IR and

light. Ozone and oxygen will absorb most of the UV (UV makes

up only 7% of sunlight). Roughly half (49%) of sunlight is

IR light and greenhouse gases will absorb some of that.

The remaining 30% of the incoming sunlight is reflected or

scattered back into space (by the ground, clouds, even air

molecules).

Expt. #3 students take note.

The object of Expt. #3 is to measure the

energy in the sunlight arriving at the ground here in

Tucson. About 2 calories of sunlight energy pass through a

one square centimeter area every minute at the top of the

atmosphere. Since about 50% of that will reach the ground,

you should get a value of about 1 calorie/(cm2

min).

The first question on the In-class

Assignment follows up on what we have just learned.

|

|

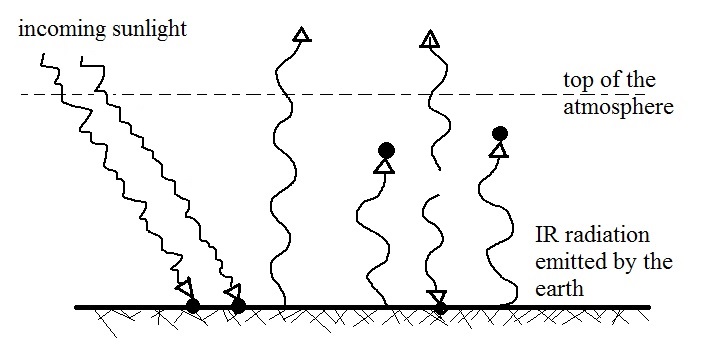

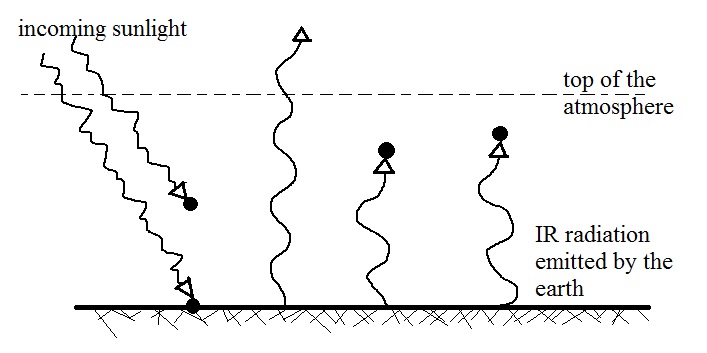

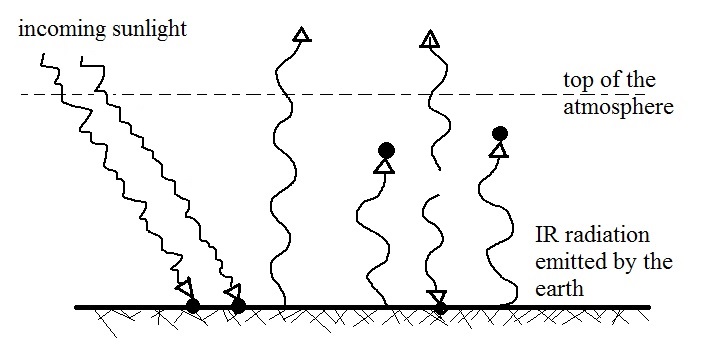

Here is our simplified

version of the greenhouse effect from the other day.

This figure is in energy balance

|

This is a more realistic

representation because it allows only half of the incoming

sunlight to reach the ground. The other half is

absorbed by the atmosphere.

As shown here the figure is incomplete and is not in

energy balance. The atmosphere is absorbing 3 units

of energy but not emitting any. We need to add 3

arrows of emitted energy. The question is what

direction to send them, up or down.

|

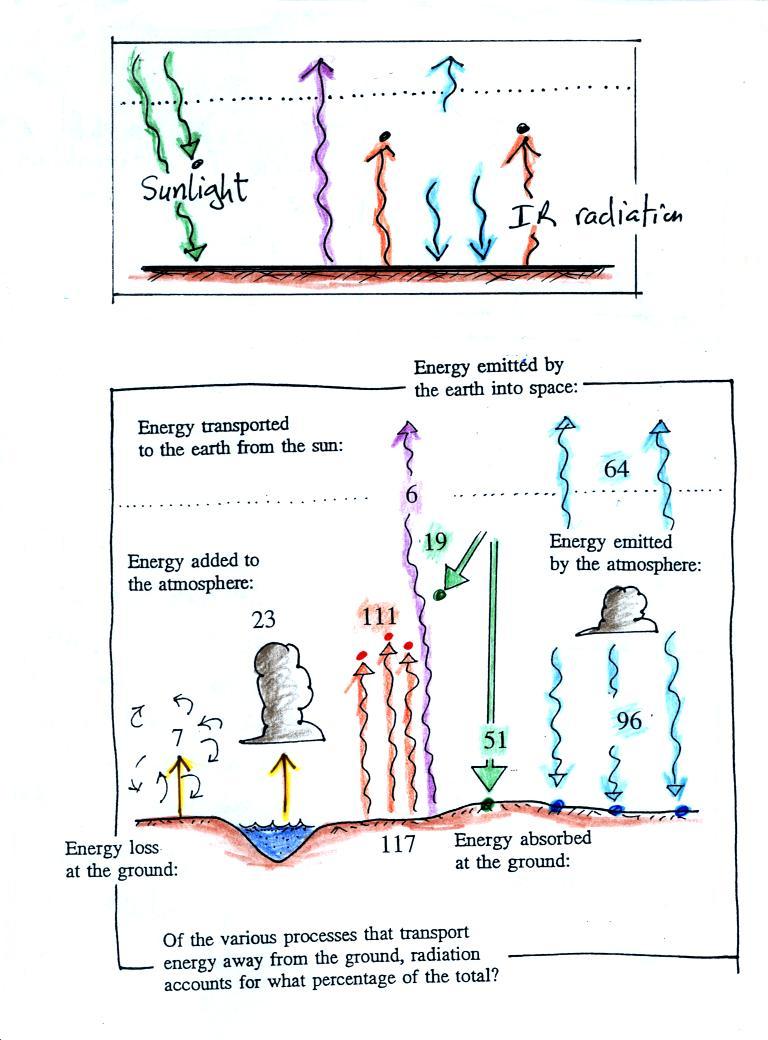

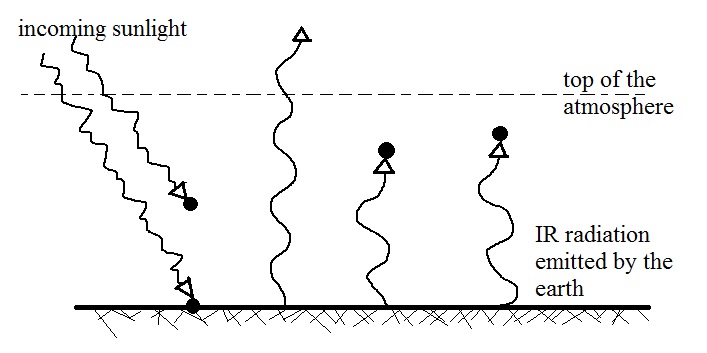

A more realistic picture of energy balance on the earth

The top part of the figure below is our new and improved but

still simplified representation of energy balance and the

greenhouse effect.

In the top figure you should recognize the incoming

sunlight (green), IR emitted by the ground that passes through the

atmosphere (violet), IR radiation emitted by the ground that is

absorbed by greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (orange) and IR

radiation emitted by the atmosphere (blue).

The lower part of the figure is pretty complicated. It would

be difficult to start with this figure and find the greenhouse

effect in it. That's why we used a simplified version.

Once you understand the upper figure, you should be able to find

and understand the corresponding parts in the lower figure (I've

tried to use the same colors for each of the corresponding parts).

The figure assumes that 100 units of sunlight energy are

arriving at the top of the atmosphere. About half of the

incoming sunlight (51 units in green, we rounded that down to 50

in an earlier figure) reaches the ground and is absorbed. 19

units of sunlight (we rounded that up to 20 in the earlier figure)

are absorbed by gases in the atmosphere. The 30 units of

reflected sunlight weren't included in the figure.

The ground emits a total of 117 units of IR light. Only 6

shine through the atmosphere and go into space. The

remaining 111 units are absorbed by greenhouse gases.

There were 3 somewhat surprising things to

notice in the figure.

(1). How can the

ground be emitting more energy (117 units) than it gets from

the sun (51 units ) and still be in energy balance?

The answer is that the ground isn't just receiving sunlight

energy. It is also getting energy from the atmosphere.

That's thanks to the greenhouse effect. Most of the energy

emitted by the ground is absorbed by greenhouse gases in the

atmosphere. The atmosphere then emits some of this energy

downwards. The ground gets back some of what it would

otherwise have lost.

If you're really paying attention you would notice that 117 units

emitted doesn't balance 96 + 51 = 147 units absorbed. The

surface is emitting 117 units but an additional 30 units are being

carried from the ground to the atmosphere by conduction,

convection, and latent heat (at the far left of the figure).

That brings everything into balance (117 + 30 = 147). Note

how much smaller the energy transport by conduction, convection,

and latent heat are compared to radiant energy transport.

(2).

Why are the amounts of energy emitted upward (64

units) and downward (96 units) different?

One reason might be that the lower atmosphere is warmer than the

upper atmosphere (warm objects emit more energy than cold

objects). But I think a better explanation is that there is

more air in the bottom of the atmosphere (the air is denser) than

near the top of the atmosphere. It is the air in the

atmosphere that is emitting radiation. More air = more

emission.

Note that the atmosphere is emitting more energy downward than

upward in our simplified version of the greenhouse effect.

(3).

The ground is receiving more energy from the

atmosphere (96 units) than it gets from the sun (51 units)!

Doesn't that seem surprising? I think the main reason for

this is that the sun just shines for part of the day (half the day

on average over the course of a year). We receive energy

from the atmosphere 24 hours per day, 365 days per year.

A common misconception about the cause of global

warming.

Many people know that sunlight contains UV light and that the

ozone layer absorbs much of this dangerous type of high energy

radiation. People also know that release of chemicals such

as CFCs are destroying stratospheric ozone and letting some of

this UV light reach the ground. That is all correct.

But then they conclude that it is this additional UV energy

reaching the ground that is causing the globe to warm. This is not correct.

There isn't enough additional UV light to cause significant

warming. The additional UV light will cause cataracts and

skin cancer and those kinds of problems but not global warming.

If all 7% of the UV light in sunlight were to reach the ground

it probably would cause some warming. But it probably

wouldn't matter because some of the shortest wavelength and most

energetic forms of UV light would probably kill us and most other

forms of life on earth. We wouldn't be around long enough to

have to worry about climate change. Ultraviolet Light is the

subject of one of the new 1S1P

Report topics.

Enhancement of the greenhouse effect and global warming

Here's the real cause of global warming and the reason for

concern (this is also the last time you'll see these

energy balance pictures)

The figure (p. 72b in the photocopied Class Notes) on the left

shows energy balance on the earth without an atmosphere (or

with an atmosphere that doesn't contain greenhouse

gases). The ground achieves energy balance by emitting

only 2 units of energy to balance out what it is getting from

the sun. The ground wouldn't need to be very warm to do

this, only 0 F.

If you add an atmosphere and greenhouse gases, the

atmosphere will begin to absorb some of the outgoing IR

radiation. The atmosphere will also begin to emit IR

radiation, upward into space and downward toward the

ground. After a period of adjustment you end up with a

new energy balance. The ground is warmer and is now

emitting 3 units of energy even though it is only getting 2

units from the sun. It can do this because it gets a

unit of energy from the atmosphere. This is what I refer

to as the beneficial greenhouse effect. It makes the

earth more habitable by raising the average surface

temperature to 60 F.

In the right figure the concentration of greenhouse gases

has increased even more (due to human activities). The

earth might find a new energy balance. In this case the

ground would be warmer and could be emitting 4 units of

energy, but still only getting 2 units from the sun.

With more greenhouse gases, the atmosphere is now able to

absorb 3 units of the IR emitted by the ground. The

atmosphere sends 2 back to the ground and 1 up into

space. A new balance is achieved but the earth's surface

is warmer. How much warmer? That's the big

question. An even bigger question is what effects that

warming will have.

Don't worry about all the details in this figure, just notice

the trend. As greenhouse gas concentrations increase,

the earth warms.

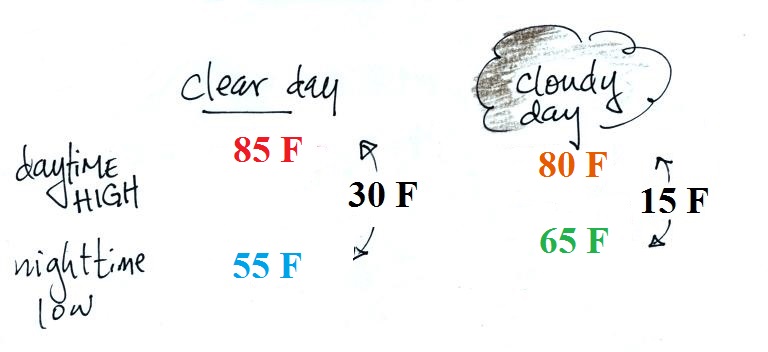

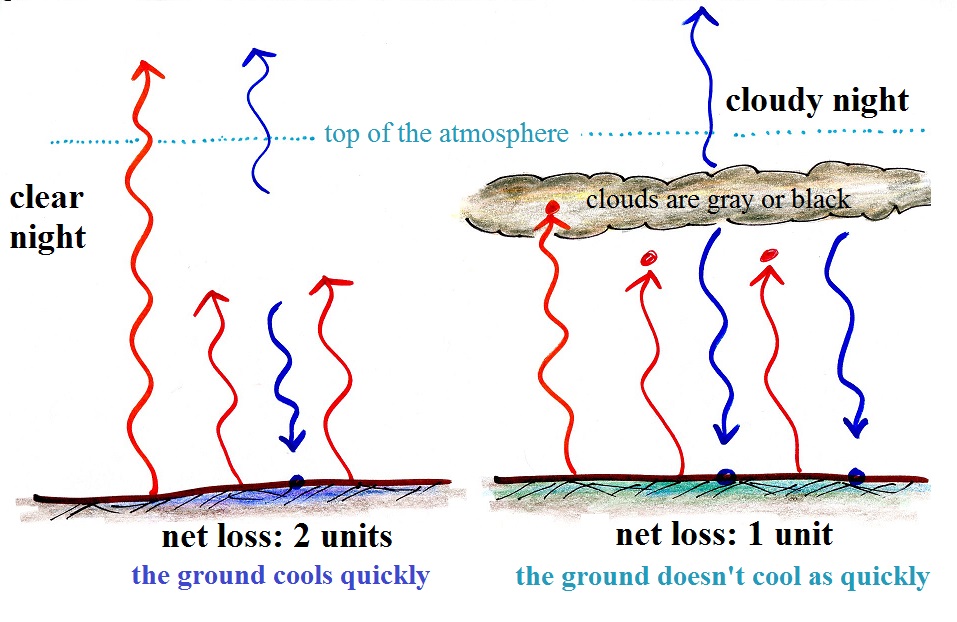

The effects of clouds on daytime high and nighttime low

temperatures

This is a topic that I often "beat to death." I want to

keep it as short and simple as I can this semester.

Here are some pretty typical high and low temperatures for this

time of year in Tucson (we've been running well above normal for

the past week or so). Notice the effects that clouds have:

they generally lower the daytime high temperature (it doesn't get

quite as hot on a cloudy day as it would on a clear day) and raise

the nighttime low temperature (it doesn't get quite as cold on a

cloudy night as it would on a clear night).

Sunlight is what warms the earth during the day. Sunlight is

mostly visible and near-IR light. Clouds are good reflectors

of visible and near IR light (clouds appear white). A

smaller fraction of the incoming sunlight will reach the ground on

a cloudy and it won't get as warm.

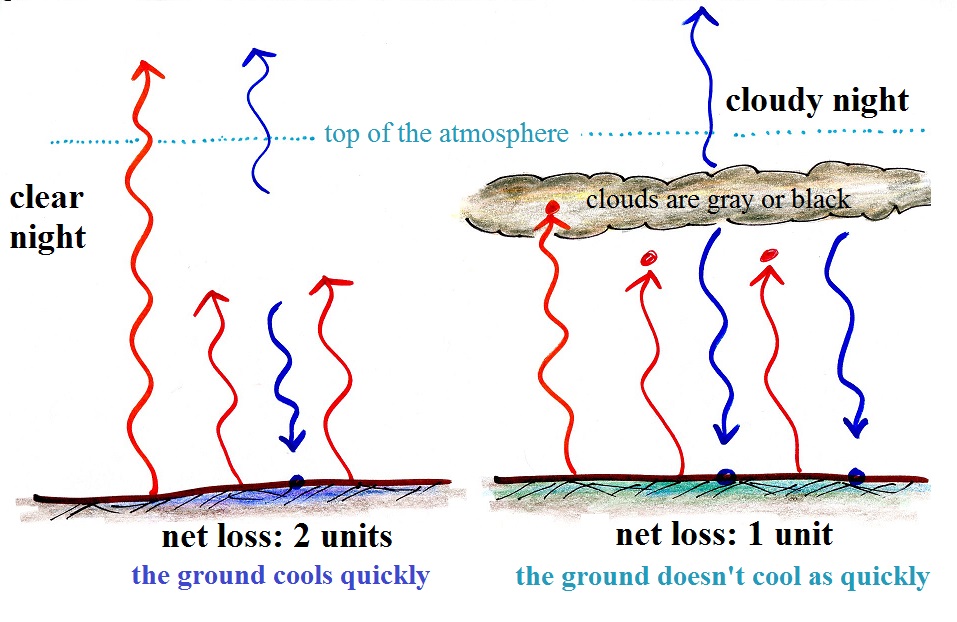

The situation is different at night. The sun is no longer

in the picture. The ground cools by emitting far-IR

light. Without an atmosphere at all this IR energy would

travel out to space and the ground would cool very quickly and get

very cold. Greenhouse gases absorb some of this IR light

emitted by the ground and re emit a portion of it back to the

ground.

It turns out that clouds are good absorbers of far-IR light too

(they absorb some of the wavelengths that greenhouse gases do

not). I've colored the cloud layer grey in the right picture

above. If our eyes were sensitive to far IR instead of

visible clouds would appear gray or black. I've also added

some orange to the gray cloud because clouds also emit far IR

light. Some of this emitted IR light is downward to

the ground and reduces the rate at which the ground cools.

It doesn't get as cold on a cloudy night as it would on a clear

night.

This is the end of the material that

will be covered on Quiz #2 coming up on Thursday this week.

The next block of material we will be

covering includes humidity variables. These are ways

of measuring and tracking the amount of moisture in the

air. We'll learn a little bit about how clouds form

and will learn how to identify and name clouds. Only 2

of the 10 basic cloud types are able to produce significant

amounts of precipitation. It's not as easy to produce

precipitation as you might think. This is something

else we'll be looking at.

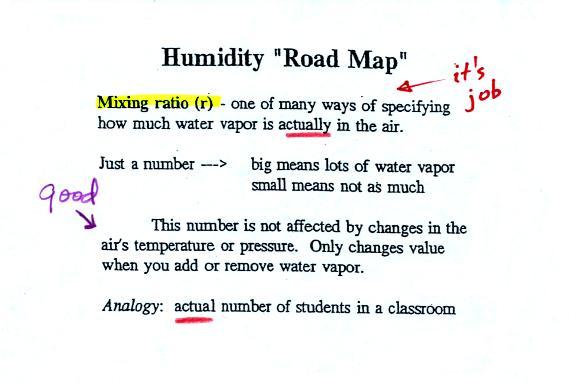

Today: introduction to humidity variables

This topic and the terms that we will

be learning are probably new and might be confusing.

So here's an introduction. We will be

mainly be interested in 4 variables:

Your task will be to learn the

"jobs" of these variables, their units, and what can cause them

to change value.

The back page of today's In-Class

Optional Assignment covered this topic.

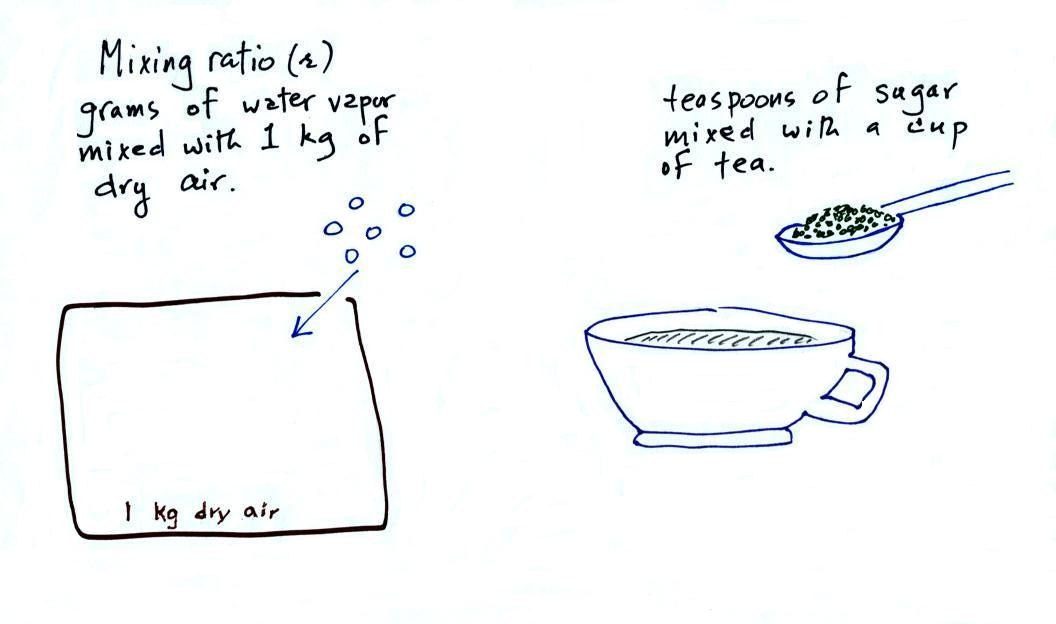

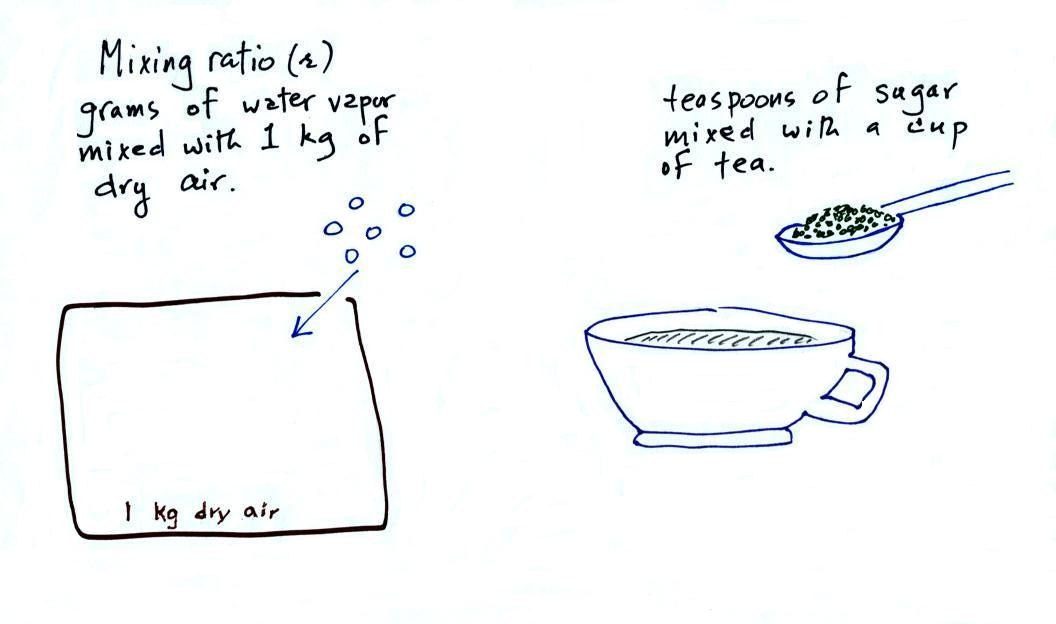

Mixing ratio ( r )

The bottom half of the figure below can

be found on p. 83 in the ClassNotes.

Mixing ratio tells you how much water vapor

is actually

in the air. Mixing ratio has units of grams of

water vapor per kilogram of dry air (the amount of water vapor

in grams mixed with a kilogram of dry air). A kilogram

of air is about one cubic meter of air (about one cubic yard

of air). Mixing ratio is basically the same idea as teaspoons

of sugar mixed in a cup of tea.

The value of the mixing ratio won't change

unless you add water vapor to or remove water vapor from the

air. Warming the air won't change the mixing

ratio. Cooling the air won't change the mixing ratio (with one exception

- when the air is cooled below its dew point temperature and

water vapor starts to condense). Since the mixing

ratio's job is to tell you how much water vapor is in the air,

you don't want it to change unless water vapor is actually

added to or removed from the air.

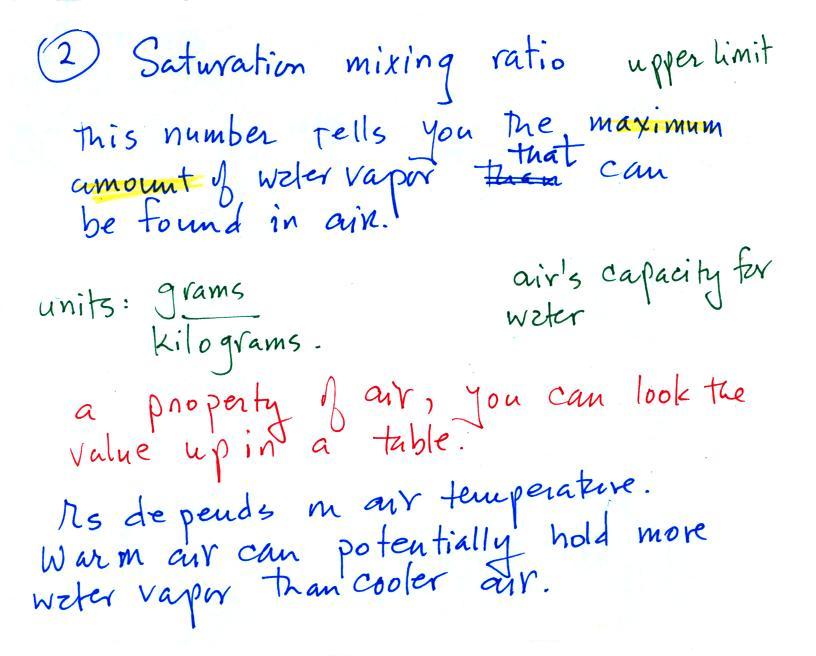

Saturation mixing ratio ( rS )

Saturation mixing ratio is just an upper limit

to how much water vapor can be found in air, the air's capacity

for water vapor. It's a property of air and depends on

the air's temperature; warm air can potentially hold

more water vapor than cold air. It doesn't

say anything about how much water vapor is actually in the air

(that's the mixing ratio's job). This

variable has the same units: grams of water vapor per kilogram

of dry air. Saturation mixing ratio values for different

air temperatures are listed and graphed on p. 86 in the

ClassNotes.

The sugar dissolved in tea analogy is still

helpful. Just as is the case with water vapor in air,

there's a limit to how much sugar can be dissolved in a cup of

hot water. And not only that, the amount depends on

temperature: you can dissolve more sugar in hot water than in cold

water.

The dependence of saturation mixing ratio on air

temperature is illustrated below:

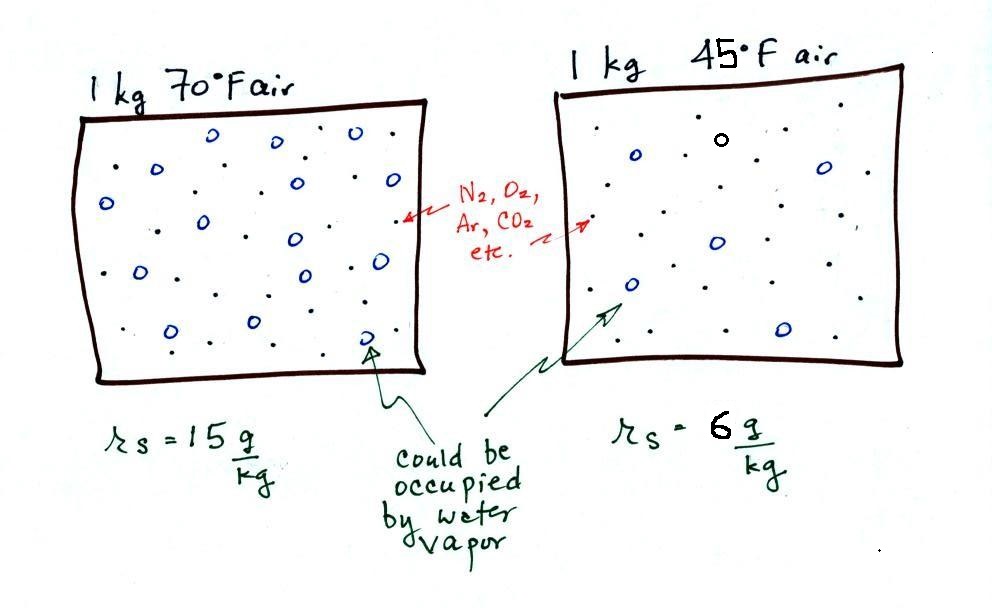

The small specks represent all

of the gases in air except for the water vapor. Each of

the open circles represents 1 gram of water vapor

that the air could potentially hold. There are 15 open

circles drawn in the 1 kg of 70 F air; each 1 kg of 70 F air

could hold up to 15 grams of water vapor. The 40 F air

only has 5 open circles; this cooler air can only

hold up to 5 grams of water vapor per kilogram of dry air.

The numbers 15 and 5 came from the table on p. 86.

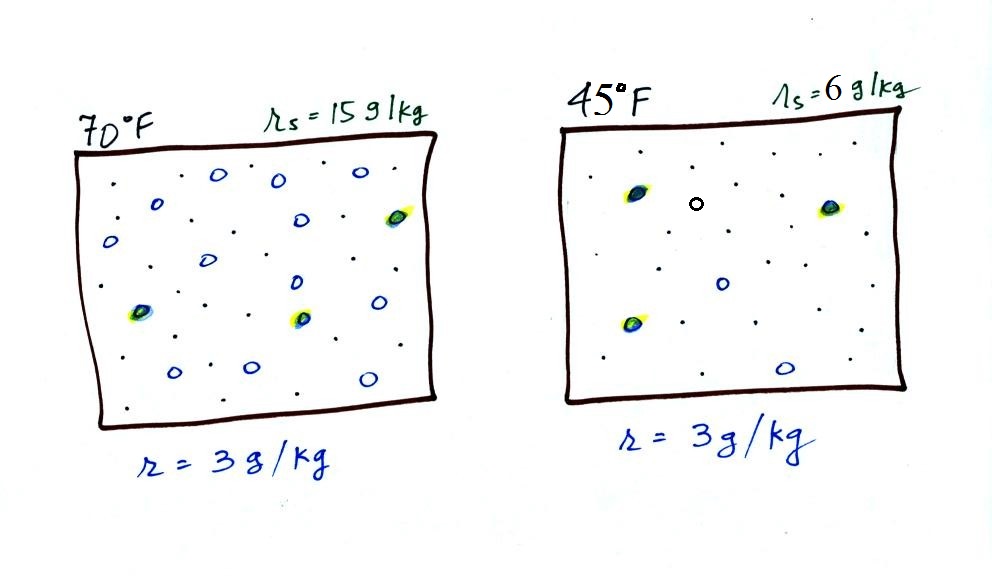

Now we have gone and actually

put some water vapor into the volumes of 70 F and 40 F air (the

open circles are colored in). The same amount, 3 grams of

water vapor, has been added to each volume of air. Three

of the open circles have been colored in. The mixing

ratio, r, is 3 g/kg in both cases. One of the

figures is almost filled to capacity, with water vapor the other

is not. That's basically what the 3rd humidity variable,

relative humidity, tells us

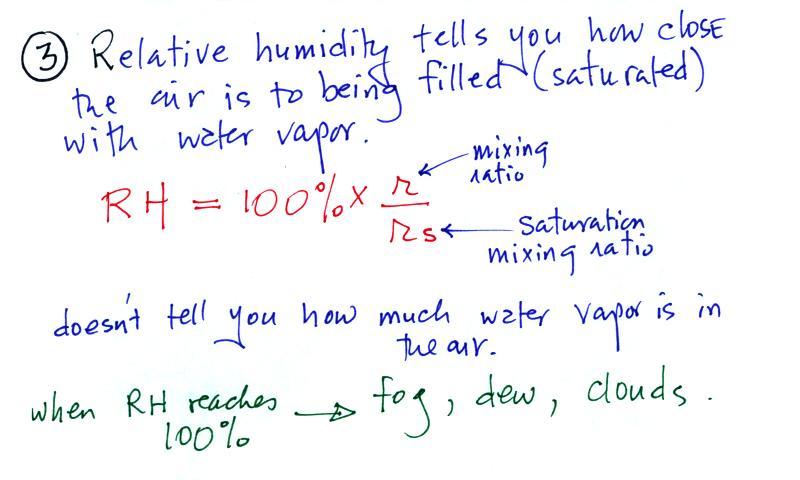

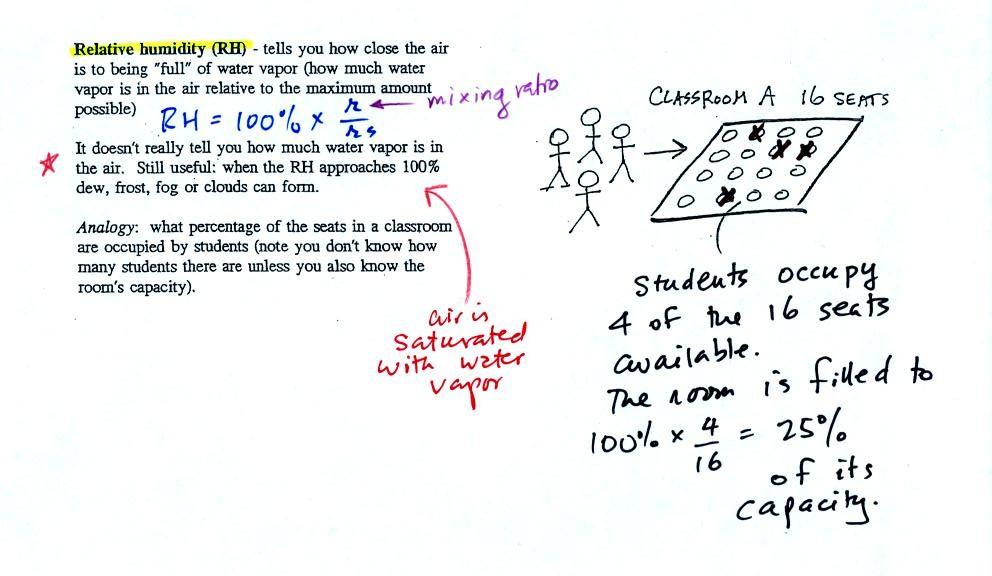

Relative humidity (RH)

|

The relative humidity is the

variable most people are familiar with. It tells you how

"full" the air is with water vapor, how close it is to

being filled to capacity with water vapor, how

close the air is to being "saturated" with water

vapor. RH has units of %.

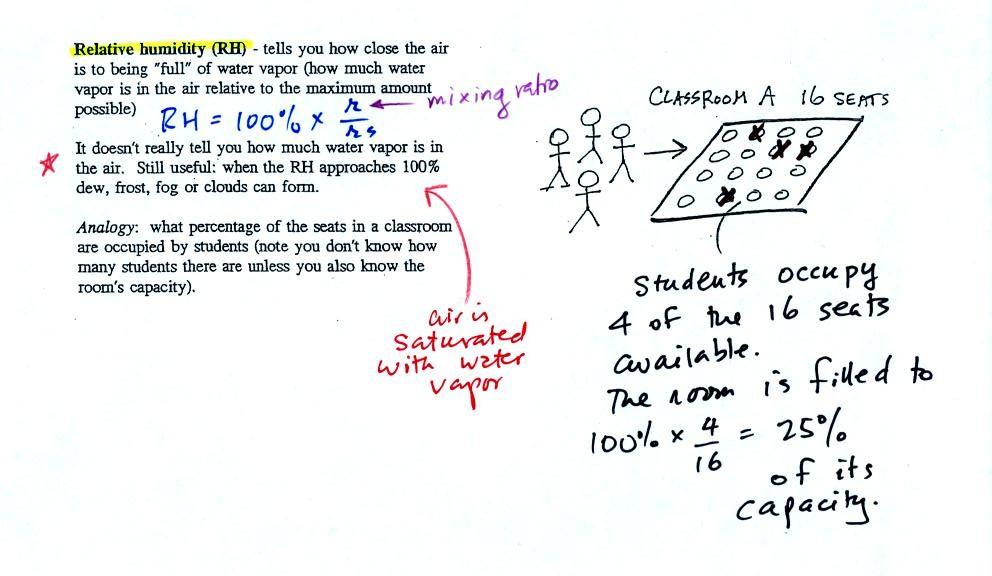

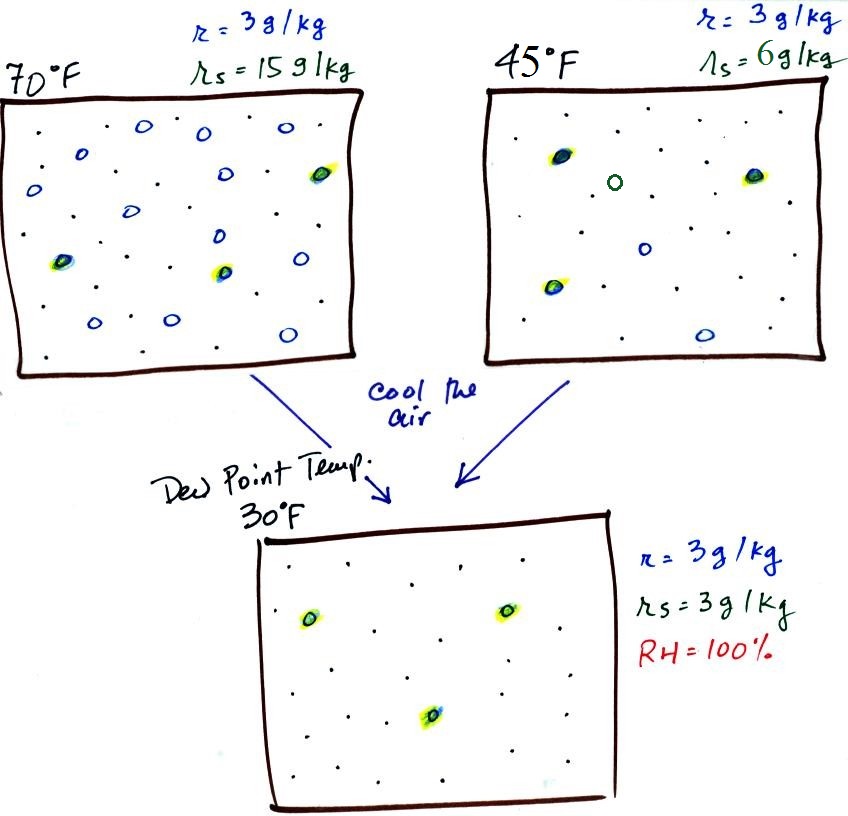

In the analogy (sketched on the right hand side of p. 83 in

the photocopied notes) 4 students wander into Classroom A which

has 16 empty seats. Classroom A is filled to

25% of its capacity. You can think of 4, the

actual number of students, as being analogous to the mixing

ratio. The classroom capacity is analogous to the

saturation mixing ratio. How full the room is is analogous

to the relative humidity.

The figure below goes back to the volumes (1 kg each) of 70 F

and 40 F air that could potentially hold 15 grams or 5 grams of

water vapor.

Both the 70 F and the 40 F air each contain 3 grams of water

vapor. The 70 F air is only filled to 20% of capacity (3 of

the 15 open circles is colored in) because this warm air's

capacity, the saturation mixing ratio, is large. The RH in

the 40 F is 60% even though it has the same actual amount of water

vapor because the 40 F air can't hold as much water

vapor and is closer to being saturated.

Something important to note: RH doesn't

really tell you how much water vapor is actually in the air.

The two volumes of air above contain the same amount of water

vapor (3 grams per kilogram) but have very different values of

relative humidity. You could just as easily have two volumes

of air with the same relative humidity but different actual

amounts of water vapor.

What is the RH good for if it doesn't tell you how much

moisture is in the air? When the RH reaches 100% dew, fog,

and clouds form. RH tells you whether clouds or fog are

about to form or not.

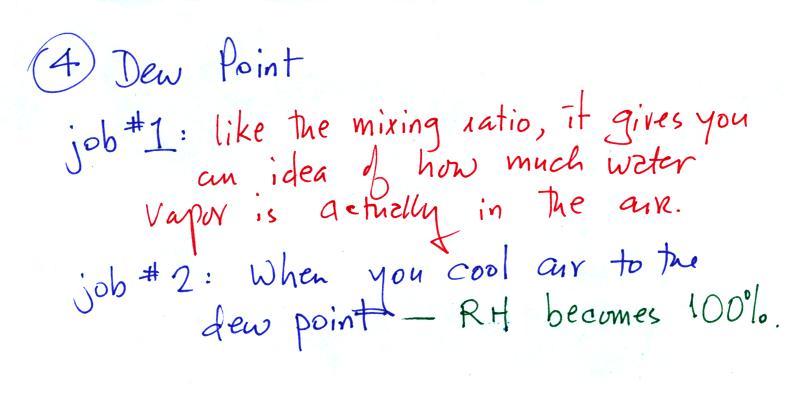

Dew point temperature

The dew point temperature has

two jobs. First it gives you an idea of the actual amount

of water vapor in the air. In this respect it is

just like the mixing ratio. If the dew point temperature

is low the air doesn't contain much water vapor. If it is

high the air contains more water vapor. This is something

we learned early in the semester.

The dew point is a temperature and has units of

oF or oC

Second the dew point tells you how much you

must cool the air in order to raise the RH to 100% (at which

point a cloud, or dew or frost, or fog would form). This

idea of cooling the air until the RH increases to 100% is

important and is something we will use a lot.

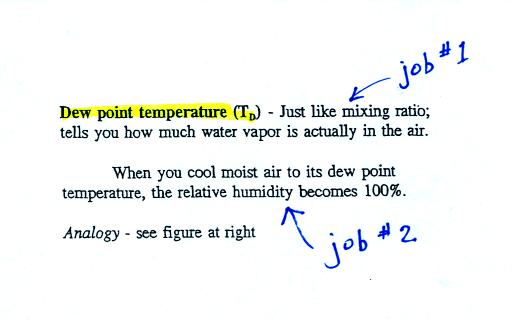

If we cool the 70 F air or the 40 F air to 30

F we would find that the saturation mixing ratio would decrease

to 3 grams/kilogram. Since the air actually contains 3

g/kg, the RH of the 30 F air would become 100%. The 30 F

air would be saturated, it would be filled to capacity with

water vapor. 30 F is the dew point temperature for 70 F

air that contains 3 grams of water vapor per kilogram of dry

air. It is also the dew point temperature for 40 F air

that contains 3 grams of water vapor per kilogram of dry air.

Because both volumes of air had the same amount of water

vapor, they both also have

the same dew point temperature.

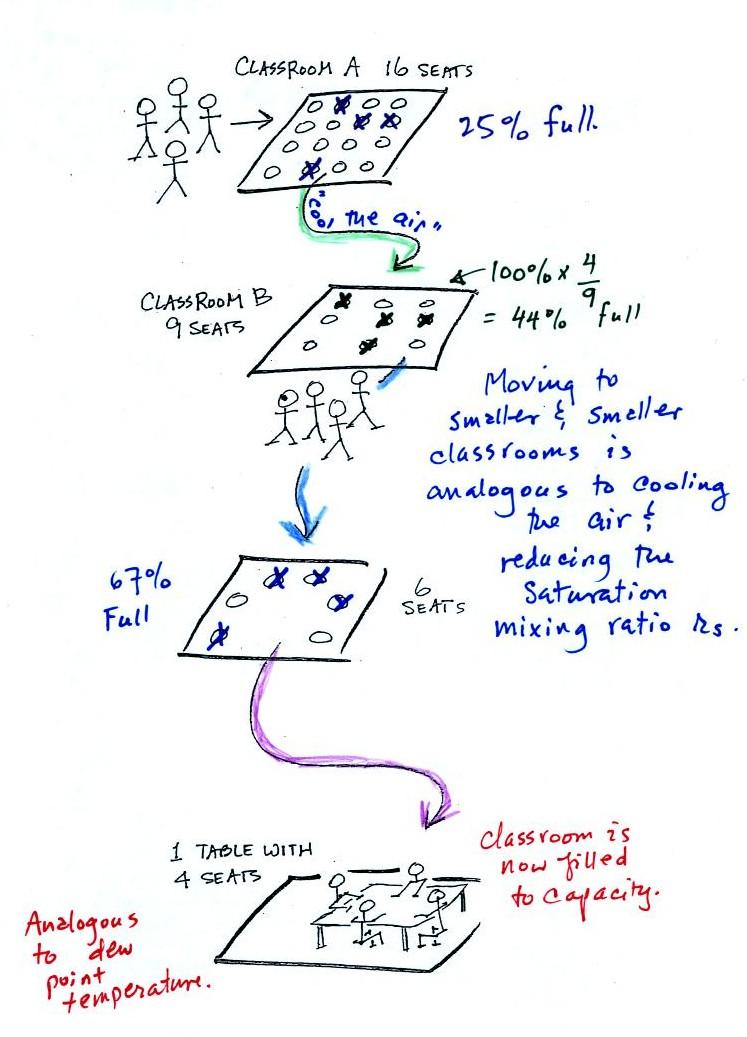

Now back to the

student/classroom analogy.

The 4 students move into classrooms of

smaller and smaller capacity. The decreasing capacity of

the classrooms is analogous to the decrease in

saturation mixing ratio that occurs when you cool air.

Eventually the students move into a classroom that they just

fill to capacity. This is analogous to

cooling the air to the dew point.