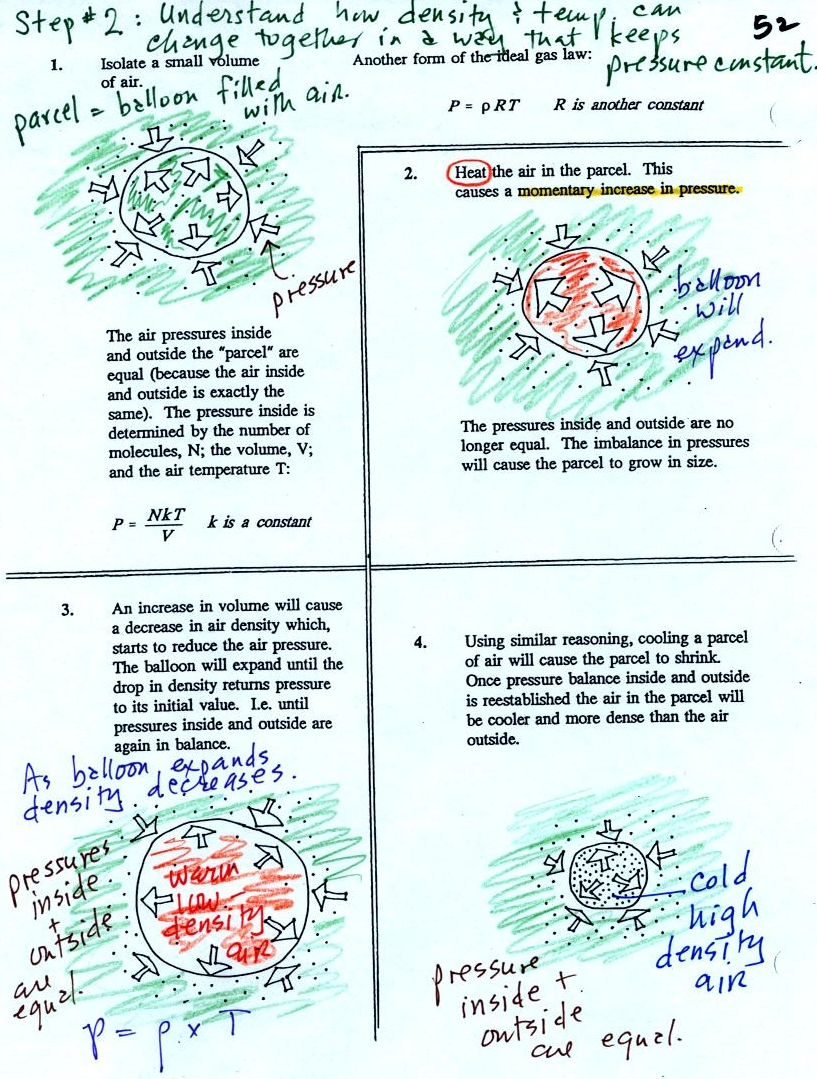

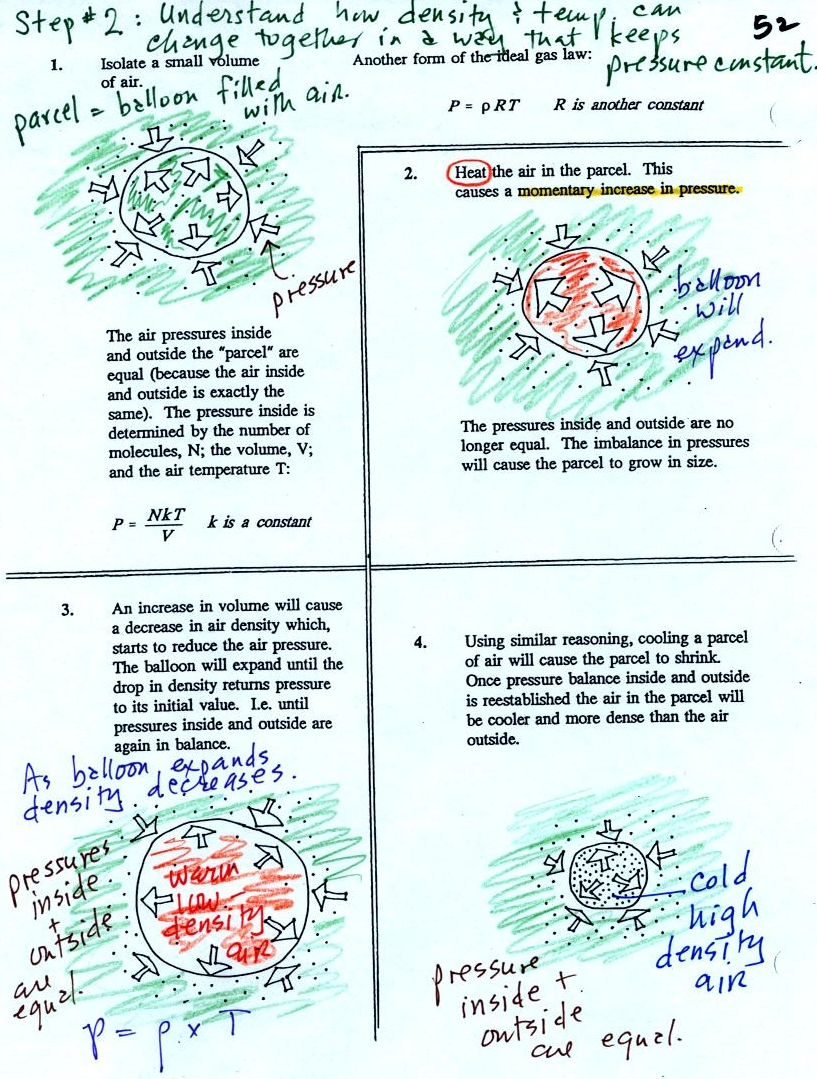

Read through the explanation on p.

52 in the photocopied

Classnotes.

These two associations:

(i)

warm air = low

density air

(ii) cold air = high density air

are important and will come up a

lot during the remainder of the

semester.

Click here if you

would like a little

more detailed, more step-by-step,

explanation of Charles Law. Otherwise proceed on to the Charles'

Law demonstration that we did in class.

Charles

Law can be demonstrated by dipping a balloon in

liquid

nitrogen. You'll find an explanation on the top of p. 54 in the

photocopied ClassNotes.

The balloon had shrunk down to practically no volume when

pulled from the liquid nitrogen. It was filled with cold high

density air. As

the balloon warmed the balloon expanded and the density of the air

inside

the balloon decreased. The volume and temperature kept changing

in a way that kept pressure constant.

Here's a summary (not shown in

class)

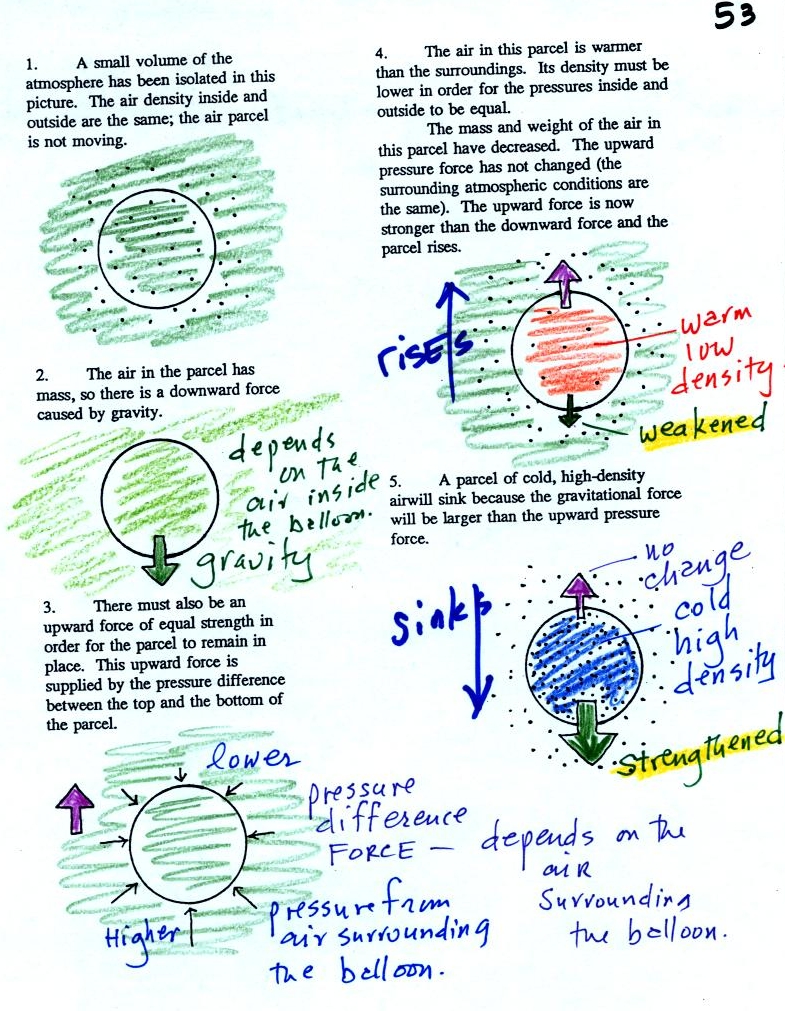

Now

finally on to step #3. Found on p. 53 in the photocopied

ClassNotes.

Basically what it comes down to is this - there are two forces

acting on a parcel (balloon) of air:

Gravity pulls downward. The strength of the gravity force depends

on the mass of the air inside

the balloon.

There is an upward pointing pressure difference force. This is

caused by the air surrounding the balloon.

When the air inside a parcel is exactly the same as the air outside,

the two forces have equal strengths and cancel out. The parcel is

neturally bouyant and doesn't rise or sink.

If you replace the air inside the balloon with warm low density air, it

won't weigh as much. The gravity force is weaker, the upward

pressure difference force wins and the balloon will rise.

Conversely if the air inside is cold high density air, it weighs

more. Gravity is stronger than the upward pressure difference

force and the balloon sinks.

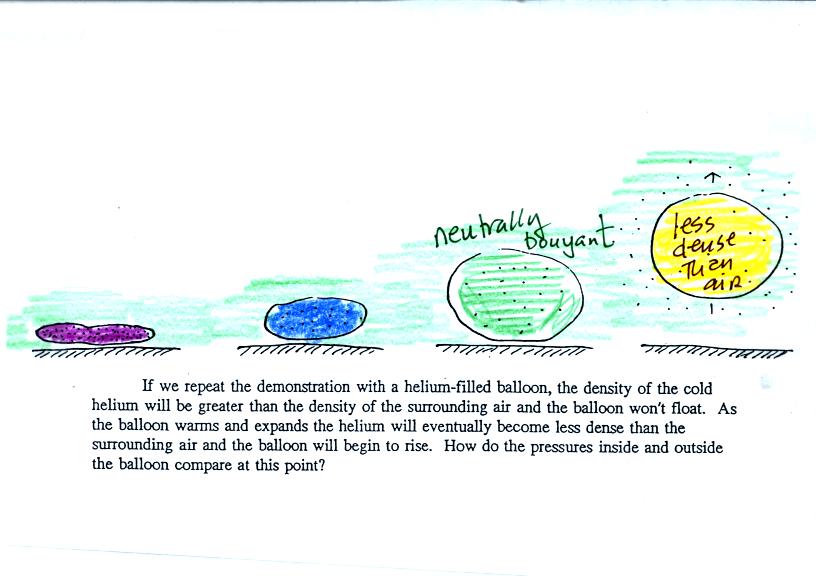

To

demonstrate free convection we modified the Charles Law

demonstration. We used

balloons filled with hydrogen instead of air (see bottom of p. 54 in

the photocopied Class

Notes). Hydrogen is less dense than air even when the

hydrogen has the same temperature as the surrounding air. A

hhydrogen-filled balloon doesn't need to warmed up in order to rise.

We dunked the helium-filled balloon

in some liquid nitrogen to cool

it

and to cause the density of the helium to increase. When

removed

from the liquid nitrogen the balloon didn't rise, the gas inside was

denser than the surrounding air (the purple and blue balloons in the

figure above). As the balloon warms and expands

its density decreases. The balloon at some point has the same

density as the air around it (green above) and is neutrally

bouyant. Eventually the balloon becomes less dense that the

surrounding air (yellow) and floats up to the ceiling.

Here's an example of where something like this happens in the

atmosphere.

At (1) sunlight reaching the ground is absorbed and warms the

ground. This in turns warms air in contact with the ground

(2). Once this air becomes warm and its density is low enough,

small blobs of air separate from the air layer at the ground and begin

to rise (3). This is called free convection; many of our summer

thunderstorms start this way.