Tuesday Apr. 1, 2008

The Experiment #3 reports were collected

today. The controls

of temperature optional assignment was also due today. The humidity optional

assignment is due at the start of class on Thursday

The revised Expt. #2 reports have been graded and were returned in

class today.

There are lots of extra office hours this week. I'm thinking

ahead to next week's quiz. You really should be reviewing the

material on the Quiz #3 Study Guide that we have already covered.

Don't leave everything until next week, there is too much

material. If you're not doing as well in this class as you think

you should be you should come by my office hours and we will try to

figure out why that is the case.

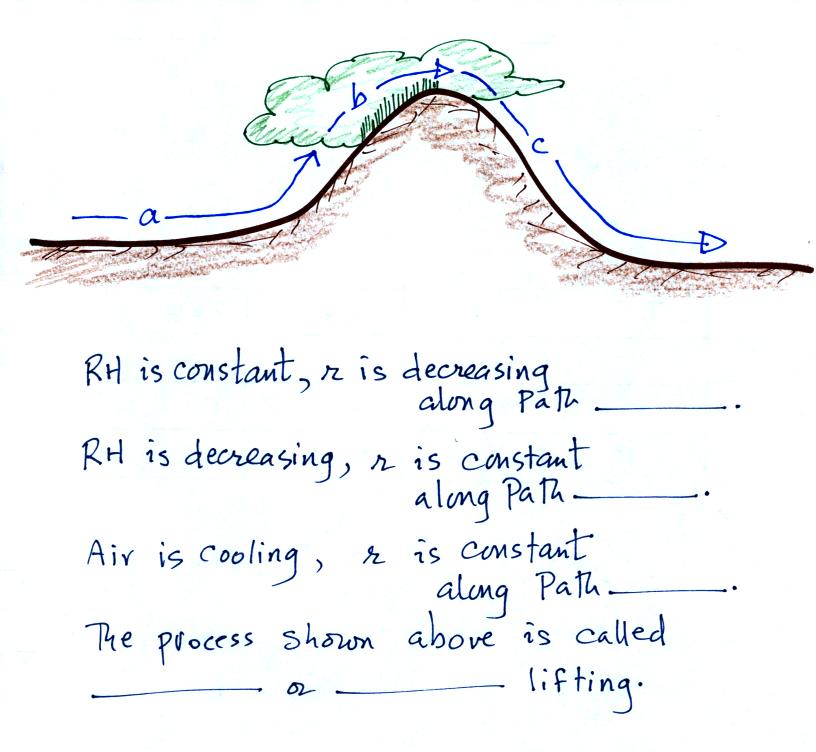

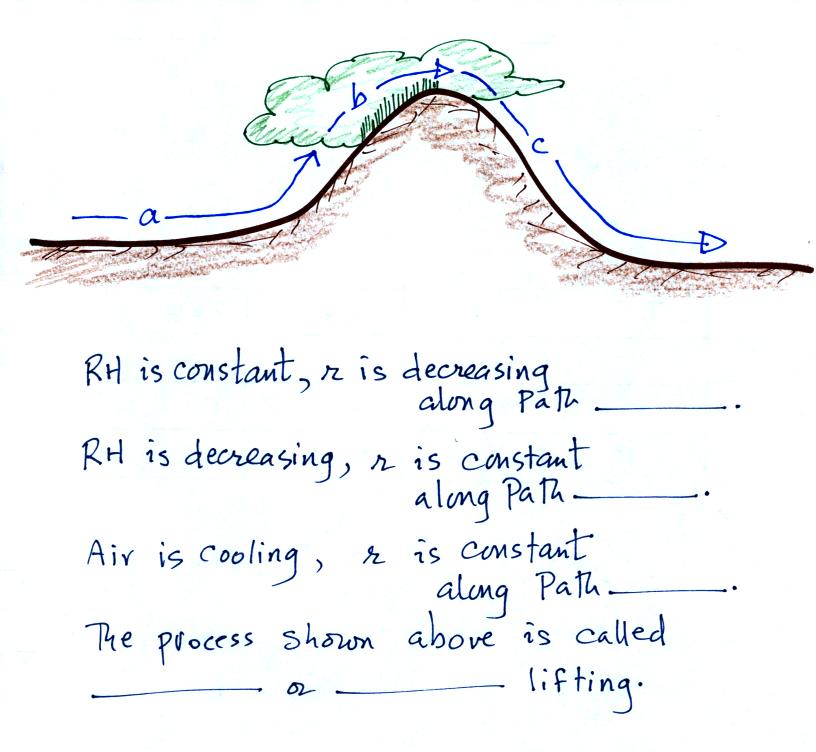

Here's a fairly tough humidity question that I put up on the screen at

the beginning of class. See if you know the answers to these

questions. If you don't then you might quickly review the

material on the study guide concerning humidity variables, drying moist

air, and the rain shadow effect (or read through the online

notes). You need to do that at some point before next week's

quiz. Once you think you understand that material a little bit

better then come back to this problem. You'll find the answers to

this question here.

Something

I forgot to mention last Thursday when discussing sling psychrometers

and measuring humidity.

You've felt the cooling when you step out of a pool on a warm dry

day.

You body tries to cool itself by perspiring during hot weather.

From

the text: "over ten million sweat glands wet the body with as much

as two liters of liquid per hour." When the relative humidity is

high, there might not be enough net evaporation to cool your

body. You might end up with heat stroke - a

potentially deadly

condition.

Just as wind and cold temperatures make it feel colder than it really

is,

a combination of high temperatures and high humidity make it feel

hotter than it is.

The wind chill temperature measures the effect of cold temperatures and

wind,

The heat index measures the effect of high temperatures and high

relative humidities.

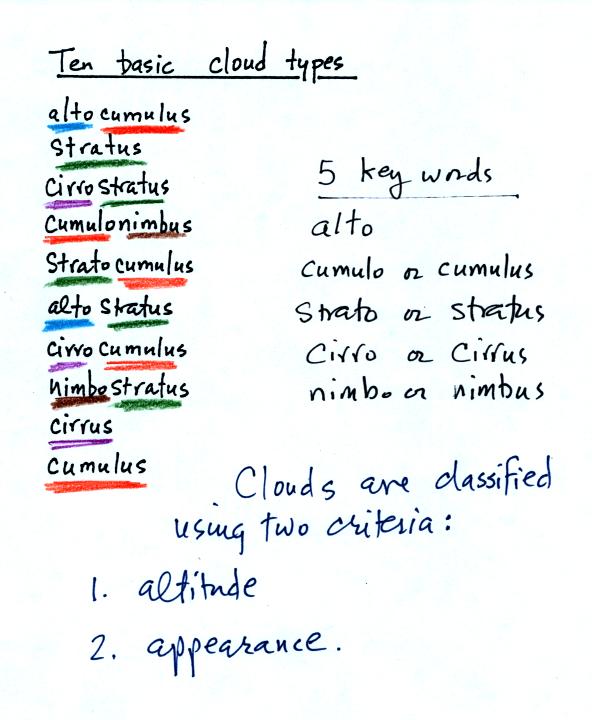

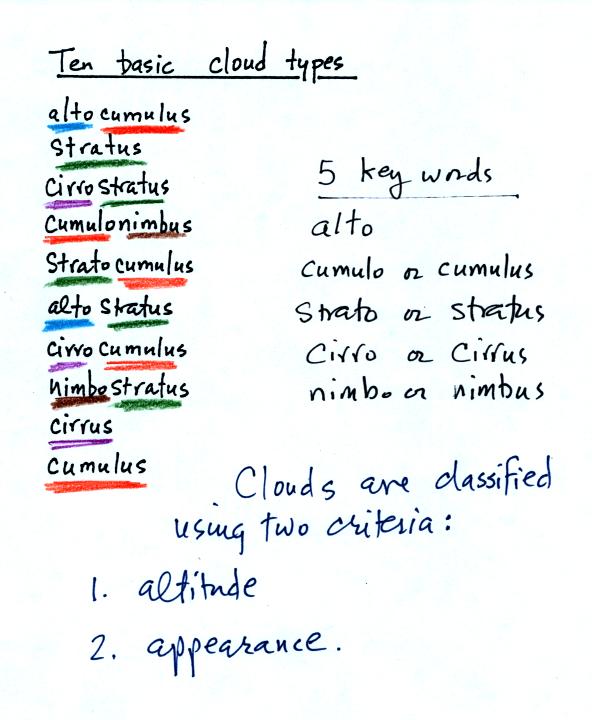

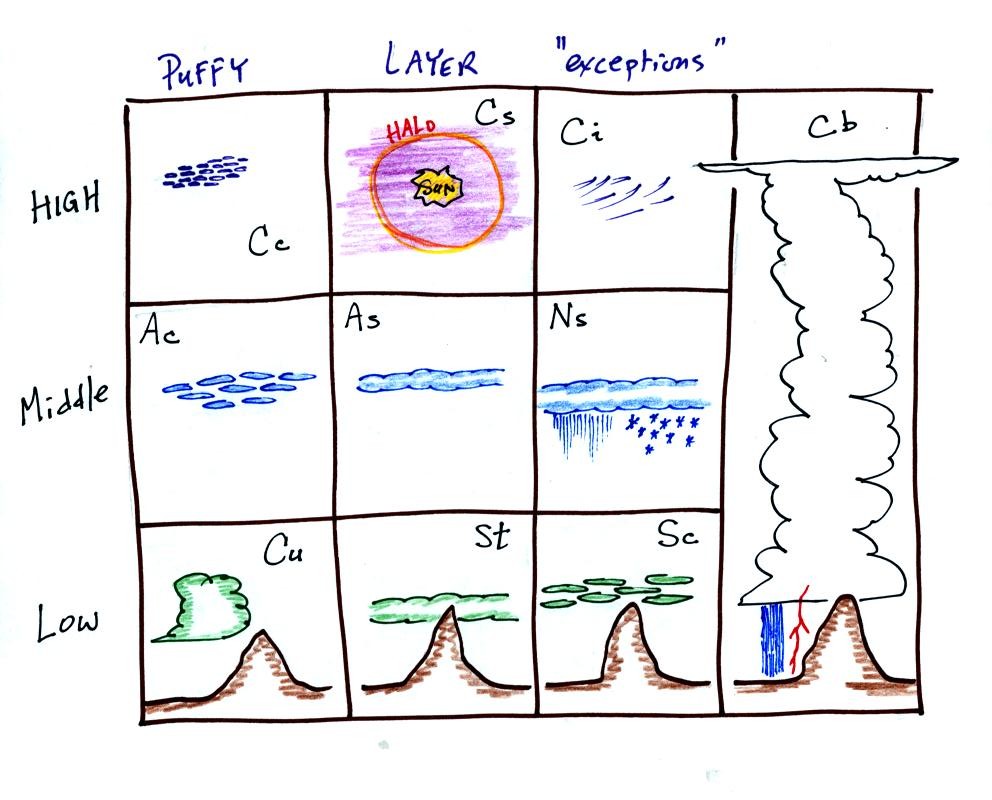

Today we

will be learning how to identify and name clouds.

The ten main cloud types are listed below (you'll find this list on p.

95 in the photocopied class notes).

You should try to learn these 10 cloud names. Not just

because

they might be on a quiz (they will) but because you will be able to

impress your friends with your knowledge. There is a smart and a

not-so-smart way of learning these names. The not-so-smart way is

to just memorize them. You will inevitably get them mixed

up. A better way is to recognize that all the cloud names are

made up of key words. The key words, we will find, tell you

something about the cloud altitude and appearance.

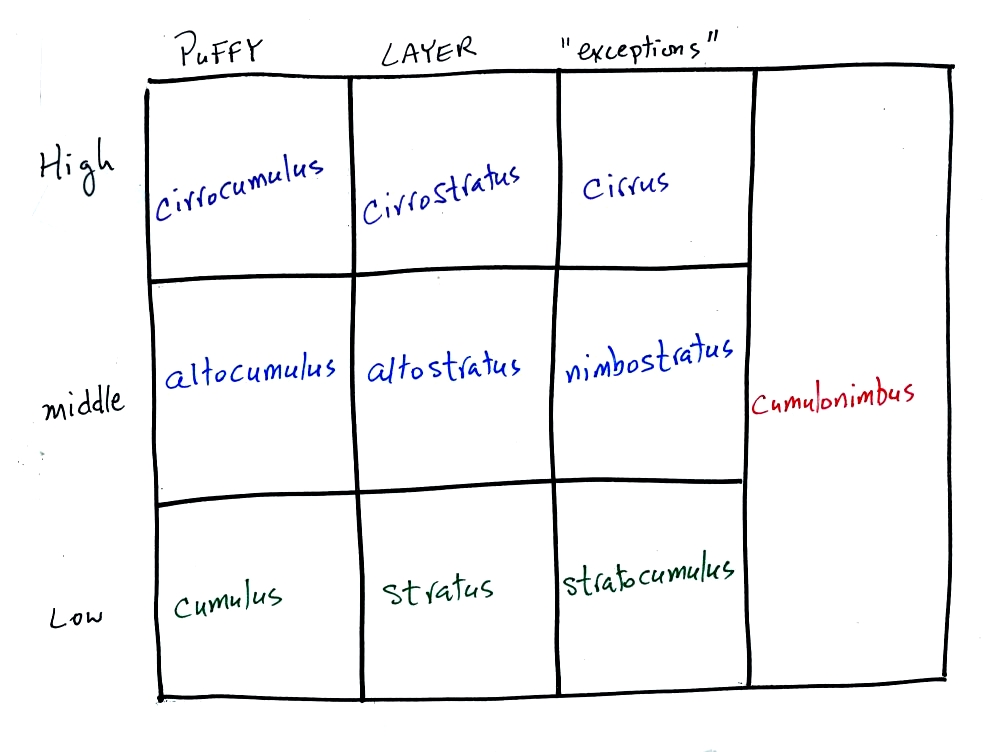

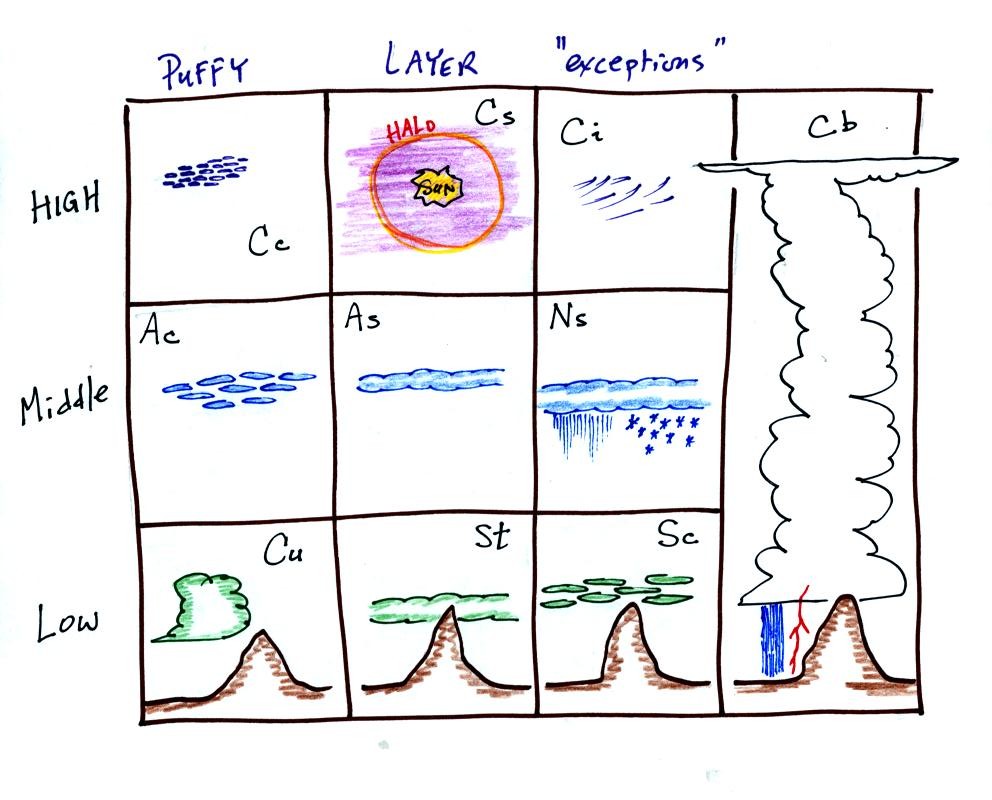

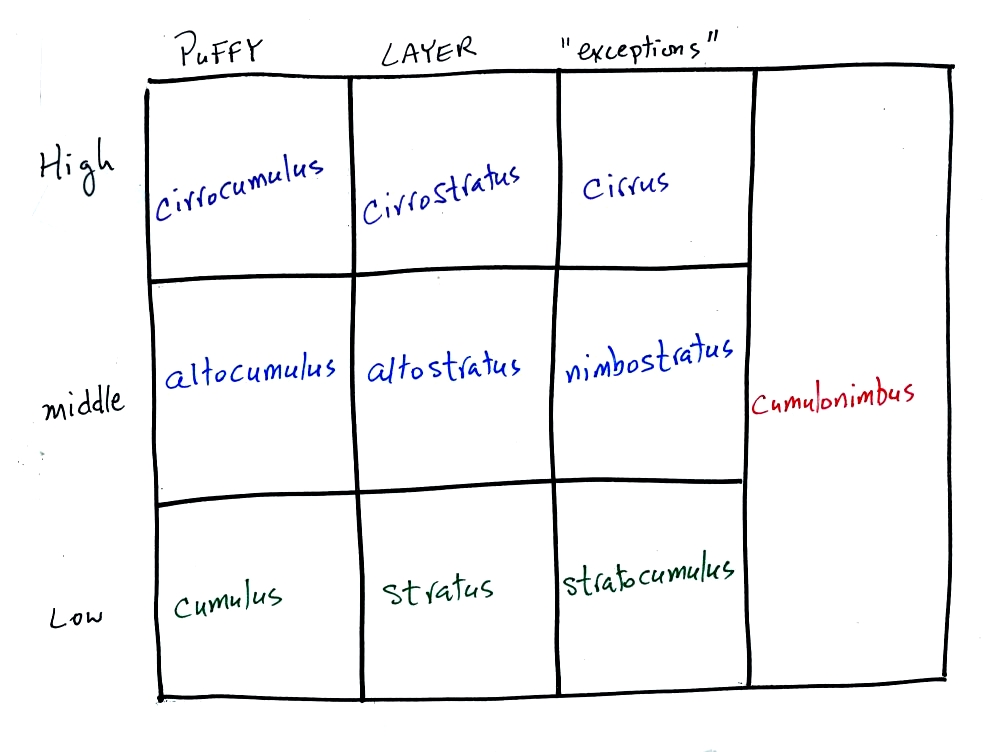

Each of the clouds above has a box reserved for it in the figure

above. Drawing a figure like this on a blank sheet of paper is a

good way to review cloud identification and classification.

Clouds are classified according to the altitude at which

they form and

the appearance of the cloud. There are two key words for altitude

and two key words for appearance.

Clouds are grouped into one of three altitude categories: high, middle

level, and low.

Cirrus or cirro

identifies a high altitude cloud. There are three types of clouds

found in the high altitude category..

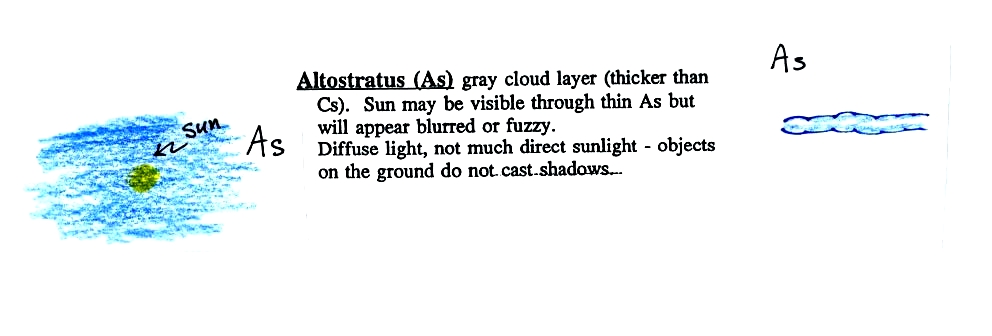

Alto in a cloud name means the

cloud is found at middle altitude.

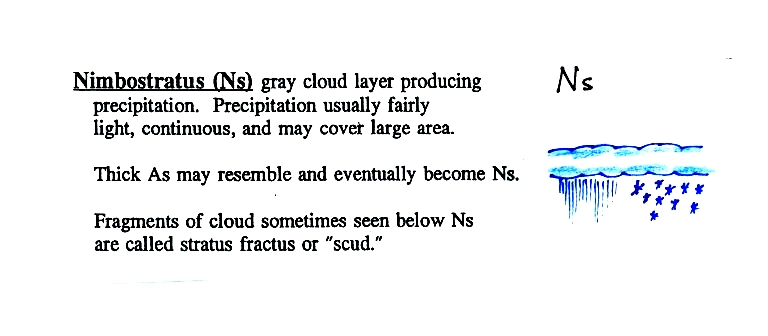

The arrow connecting altostratus and nimbostratus indicates that

they are very similar. When an altostratus cloud begins to

produce rain or snow its name is changed to nimbostratus. A

nimbostratus cloud is also often somewhat thicker and lower than an

altostratus cloud.

It is very hard to just look

up in the sky and determine a cloud's altitude. You will need to

look for other clues to distinquish between high and middle altitude

clouds. We'll learn about some of the clues when we look at cloud

pictures later in the class.

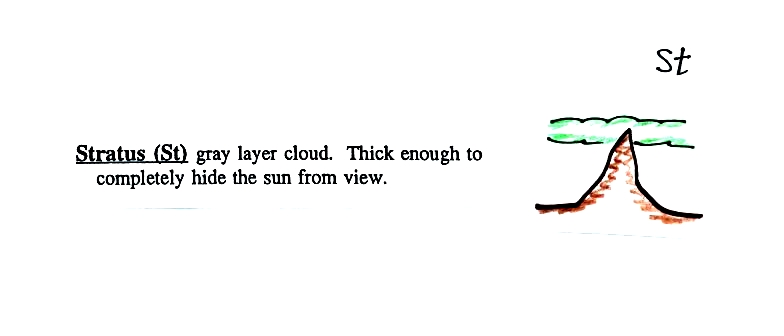

There is no key word for low altitude clouds. Low

altitude clouds

have bases that form 2 km or less above the ground. The summit of

Mt. Lemmon in the Santa Catalina mountains north of Tucson is about 2

km above the valley floor. So low altitude clouds will have bases

that form at or below the summit of Mt. Lemmon.

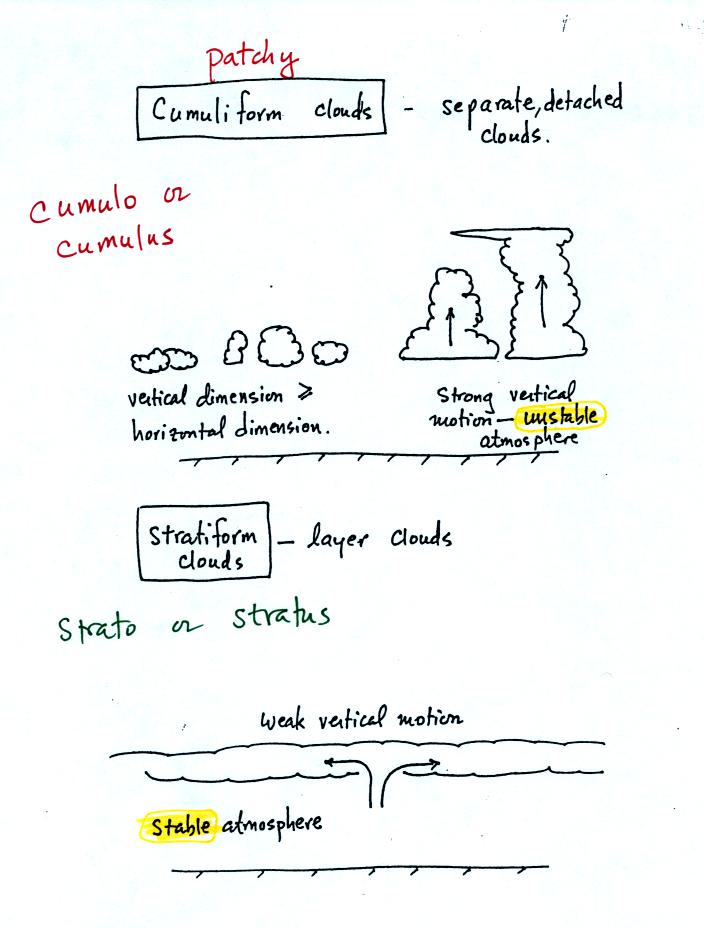

Now we will look at cloud appearance.

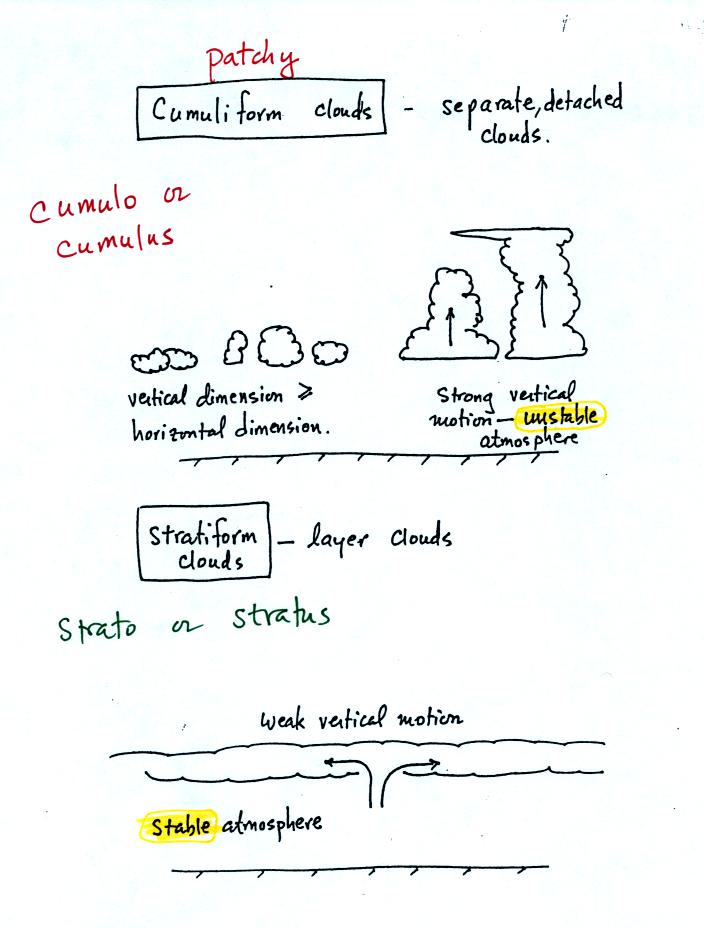

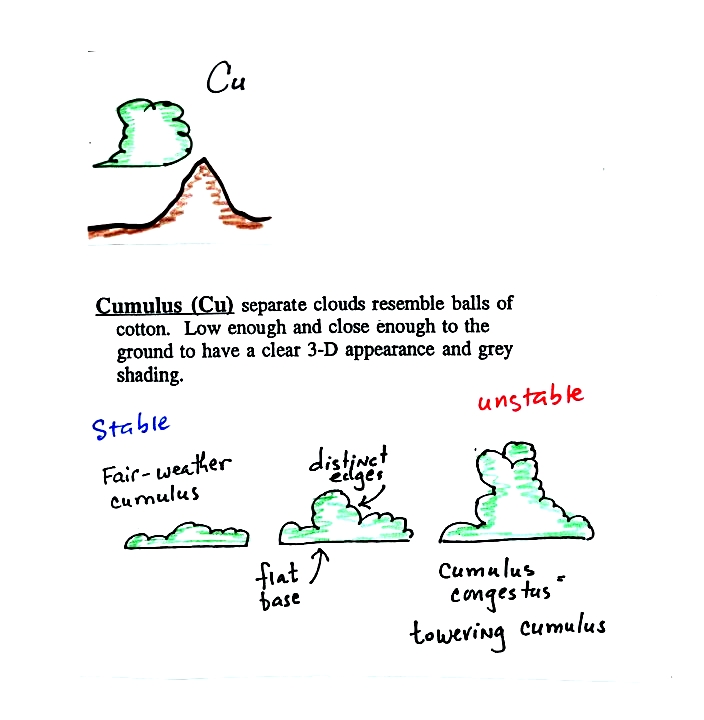

Clouds can have a patchy of puffy (or lumpy or wavy)

appearance. These are cumuliform clouds and will have cumulo or

cumulus in their

name. In an unstable atmosphere cumuliform clouds will grow

vertically.

Stratiform clouds grow horizontally and form layers. They form

when the atmosphere is stable.

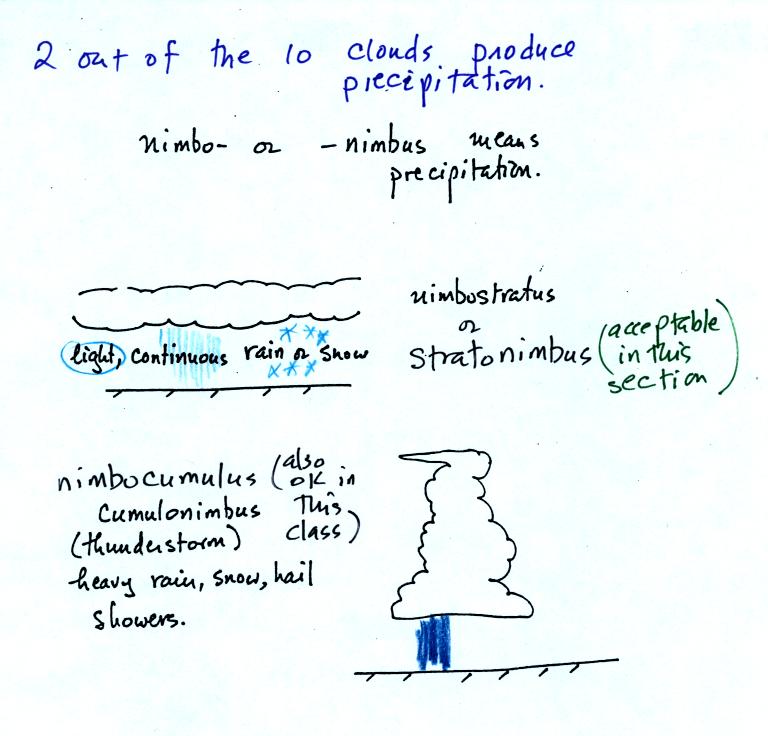

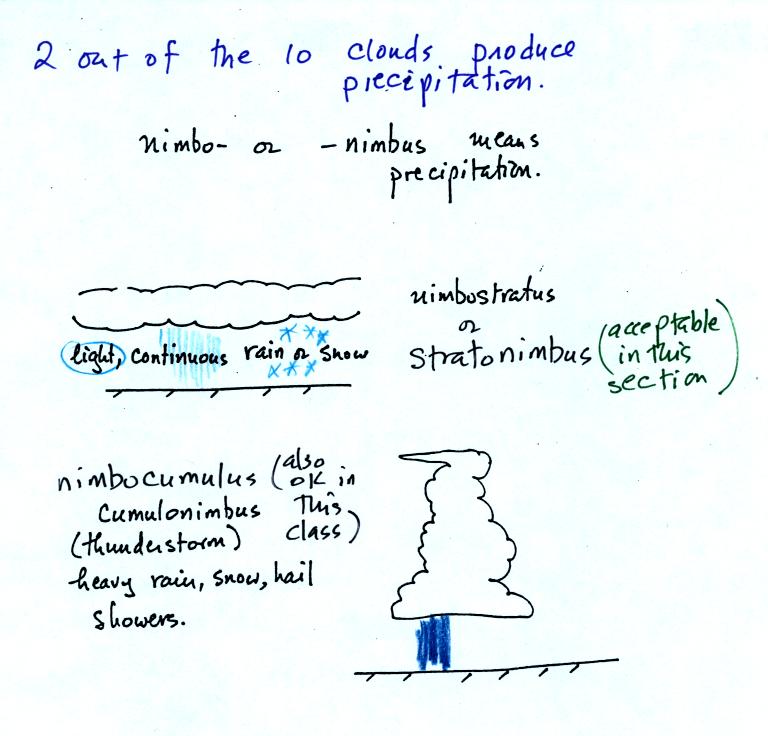

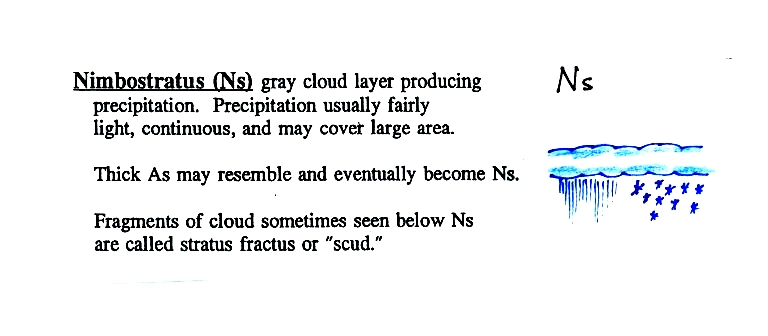

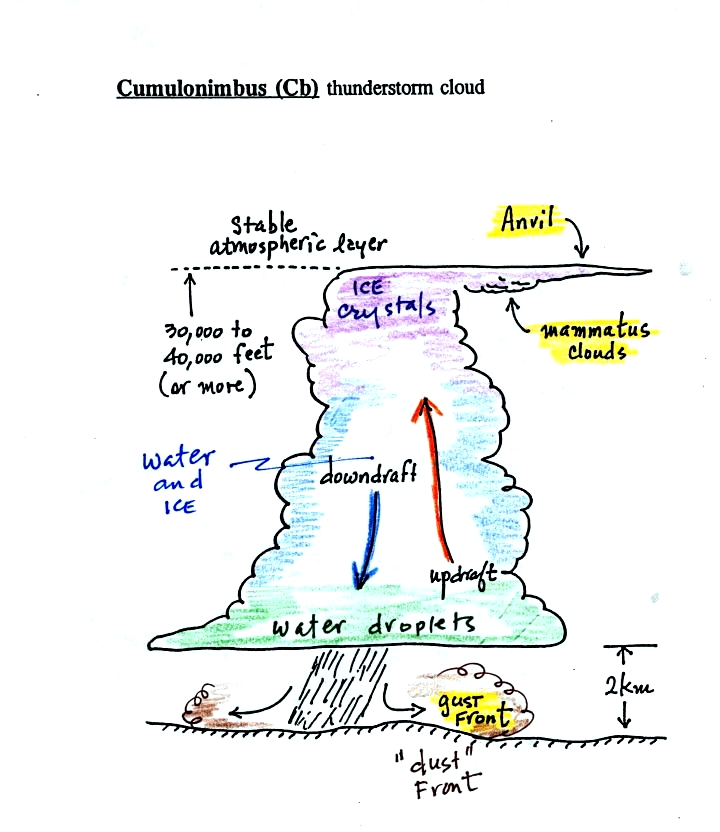

The last key word, nimbo or nimbus, means precipitation. Two of

the 10 cloud types are able to produce (significant amounts of)

precipitation.

Nimbostratus clouds tend to produce fairly light

precipitation over a large area. Cumulonimbus clouds produce

heavy showers over localized areas. Thunderstorm clouds can also

produce hail, lightning, and tornadoes. Hail would never fall

from a Ns cloud.

While you are still learning the cloud names you might put the correct

key words together in the wrong order (stratonimbus instead of

nimbostratus or nimbocumulus instead of cumulonimbus). You won't

be penalized for those kinds of errors in this class.

Here's the cloud chart from earlier. We've added the three

altitude categories along the vertical side of the figure and the two

appearance categories along the top. By the end of the class we

will add a picture to each of the boxes.

Next we

looked at 35 mm slides of most of the 10 cloud types.

Good

photographs of the ten cloud types can also be found in Chapter 4 of

the text and in a Cloud Chart at the end of the textbook. You'll

find the written descriptions of the cloud types in the images below on

pps 97-98 in the

photocopied notes.

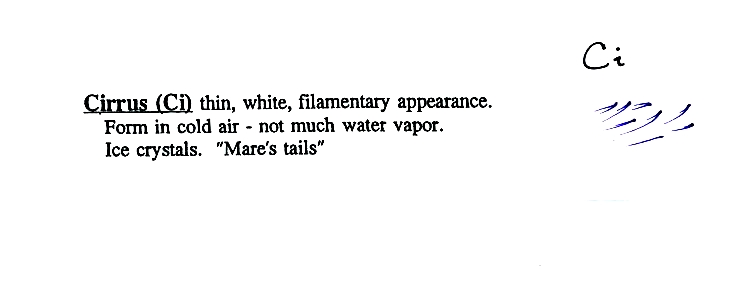

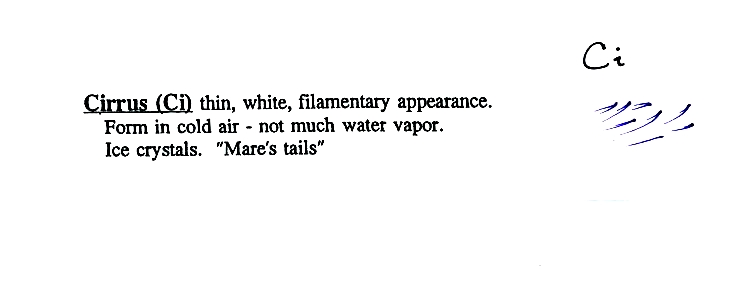

High altitude clouds are thin because the air at high

altitudes is

very cold and cold air can't contain much moisture (the saturation

mixing ratio for cold air is very small). These clouds are also

often blown around by fast high altitude winds. Filamentary means

"stringy" or "streaky". If you imagine trying

to paint a Ci cloud you would dip a stiff

brush in white paint brush it quickly and lightly across a blue colored

canvas.

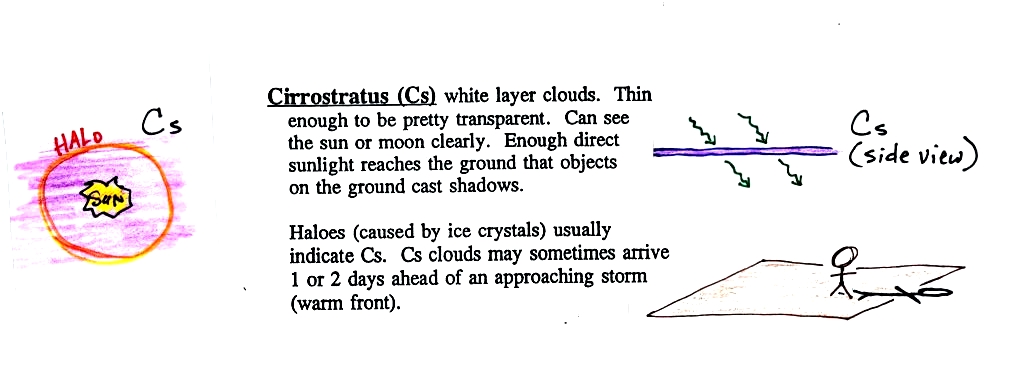

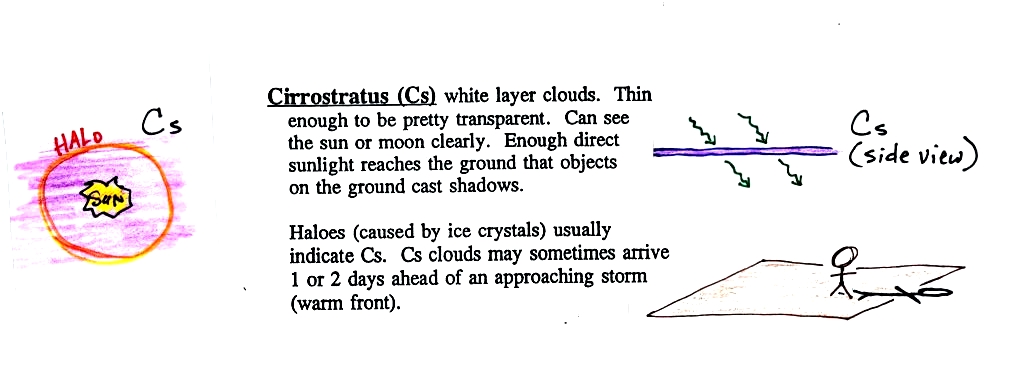

A cirrostratus cloud is a thin uniform white layer

cloud

(not purple as shown in the figure) covering

part or all of the sky. Here you might first dilute your white

paint with water and then

brush back and forth across the canvas. The thin white paint

might not be thick enough to hide the blue canvas but the white coating

on the canvas would be uniform not streaky like with a cirrus cloud.

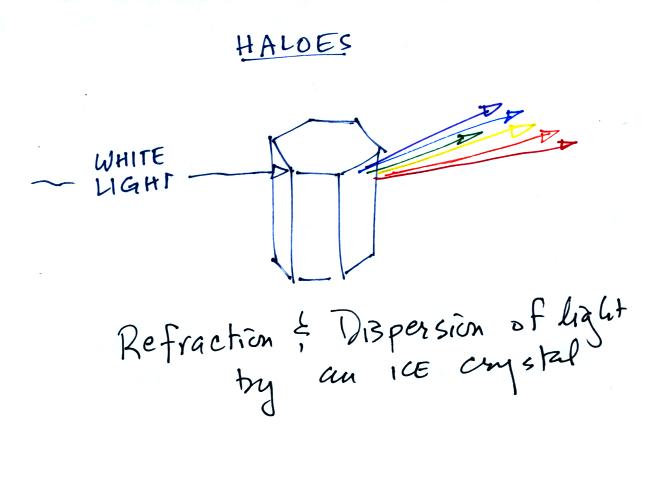

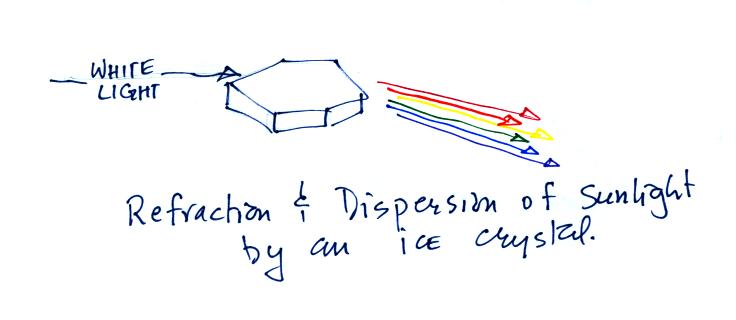

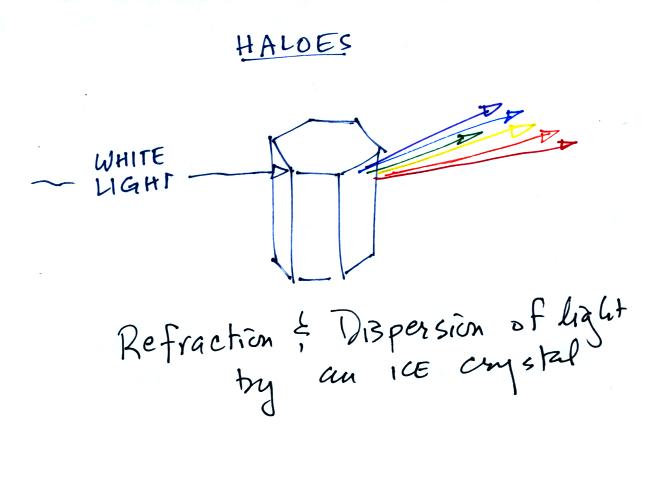

White light entering a 6 sided ice crystal is bent

(refraction). The amount of bending depends on the color

(wavelength) of the light (dispersion). The white light is split

into colors just as light passing through a glass prism. This

particular crystal is called a column and is fairly long.

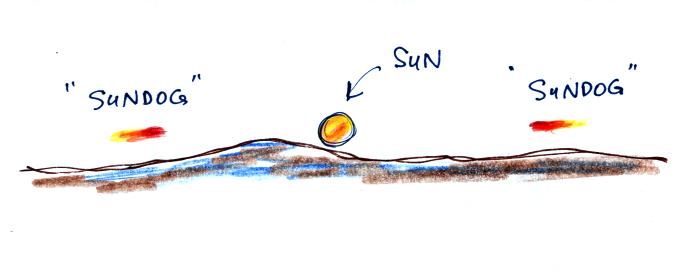

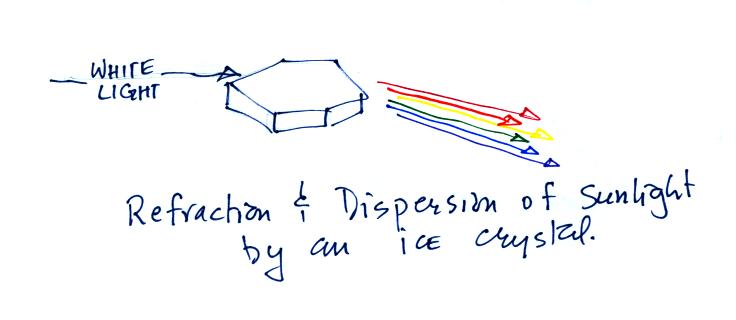

This is a flatter crystal and is called a plate. These

crystals tend to all be horizontally oriented and produce

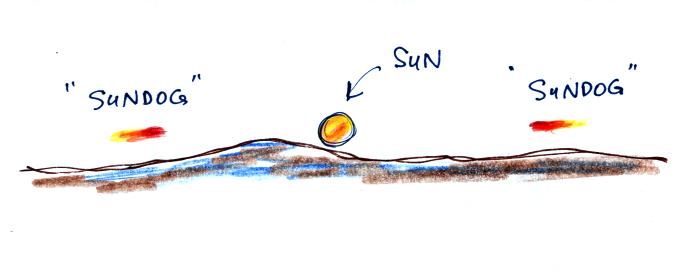

sundogs. A sketch of a sundog is shown below.

Sundogs are pretty common and are just patches of light seen to

the right and left of the rising or setting sun.

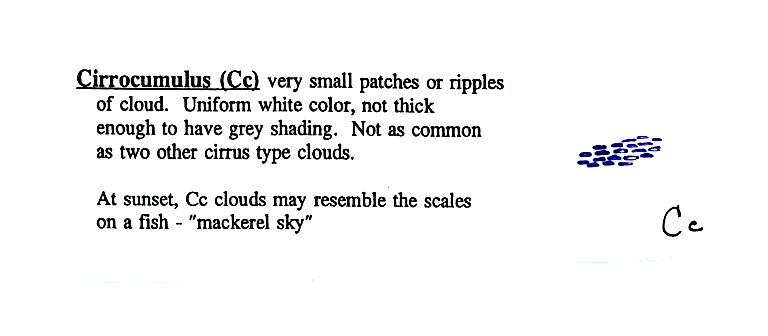

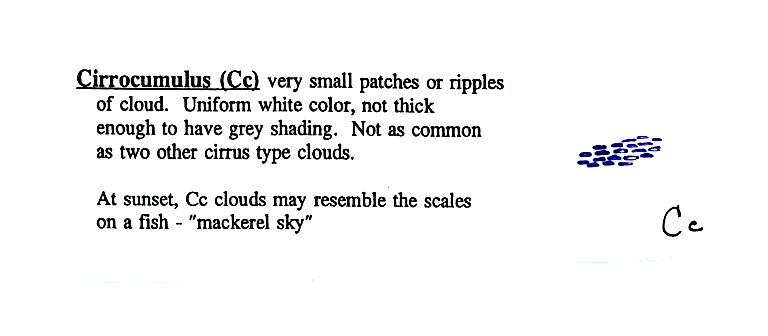

Cirrus and cirrostratus clouds are fairly common. Cirrocumulus

clouds are a little more unusual.

To paint a Cc cloud you would dip a sponge in white paint

and

press it gently against the canvas. You would leave a patchy,

splotchy

appearing cloud (sometimes you might see small ripples). It is

the patchy (or wavy) appearance that makes

it a cumuliform cloud.

If you spend enough time outside looking, you will see all of

these types of clouds.

Though, it's like wild animals, some are much more common than others.

Here are some animals that you are likely to see outdoors in the

Tucson area. Coyotes and javelina are pretty common.

Bobcats and skunks are a little less common. I'm not sure why I

put this in the online notes, it was just an impulse.

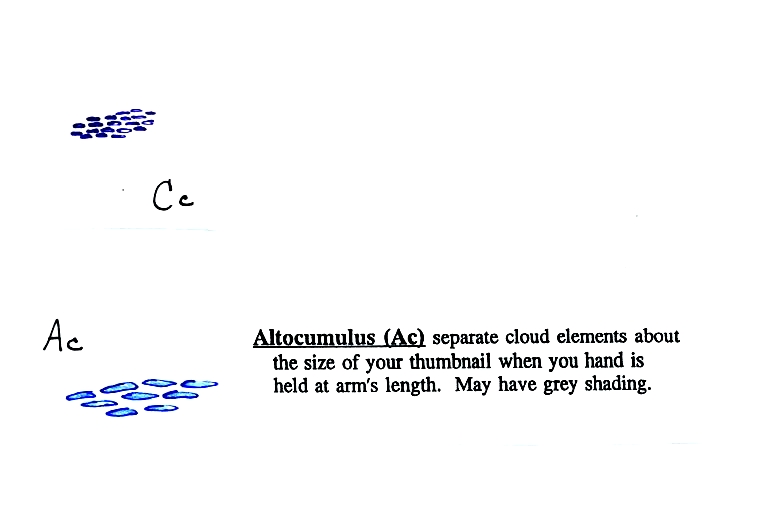

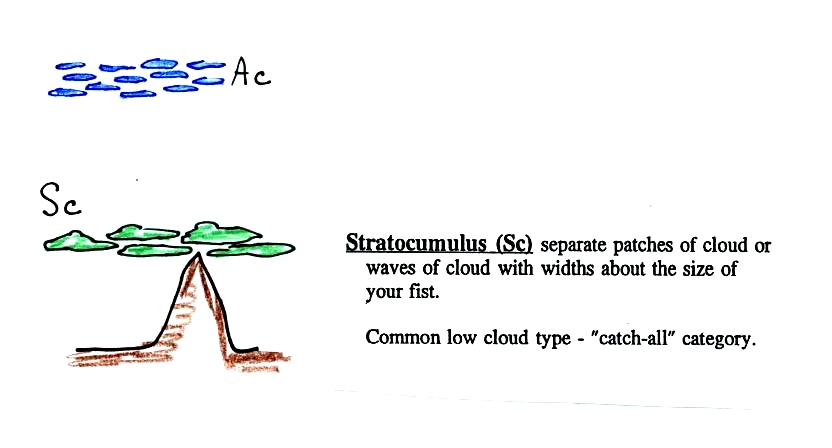

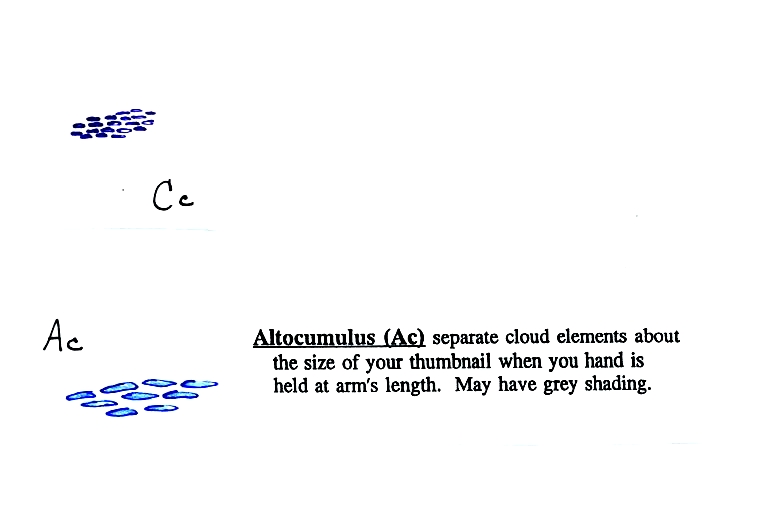

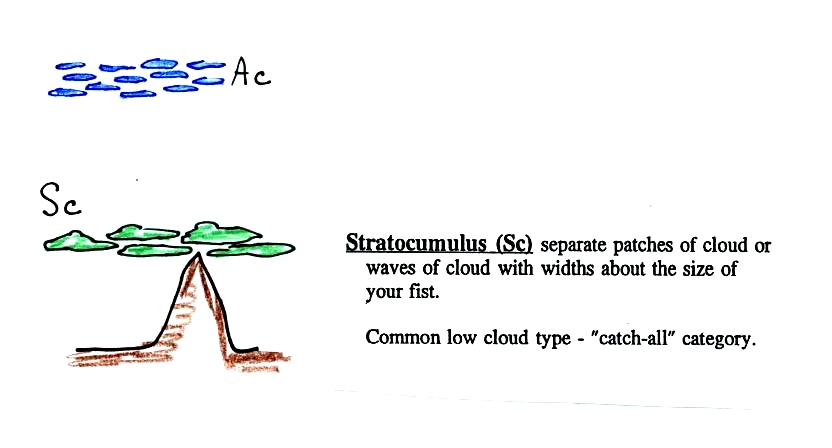

Altocumulus clouds are pretty common. Note since it is hard

to accurately judge altitude, you must

rely

on cloud element size to determine whether a cloud belongs in the high

or middle altitude category. The cloud elements in Ac clouds

appear larger than in Cc because the cloud is closer to the ground.

Lenticular clouds (see Fig. 4.33 on p. 105 in the text) are a special

type of altocumulus cloud.

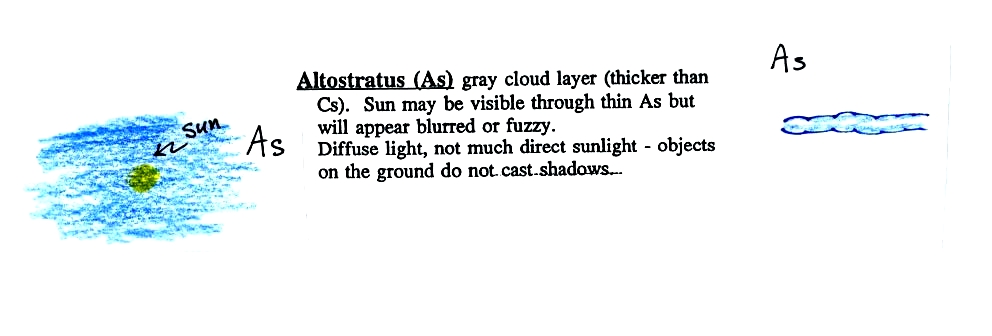

When (if) an

altostratus cloud begins to produce precipitation, its name is changed

to nimbostratus.

This cloud name is a little unusual because the two key

words for cloud

appearance have been combined. Because they are closer to the

ground, the separate patches of Sc are about fist size. The

patches of Ac, remember, were about thumb nail size.

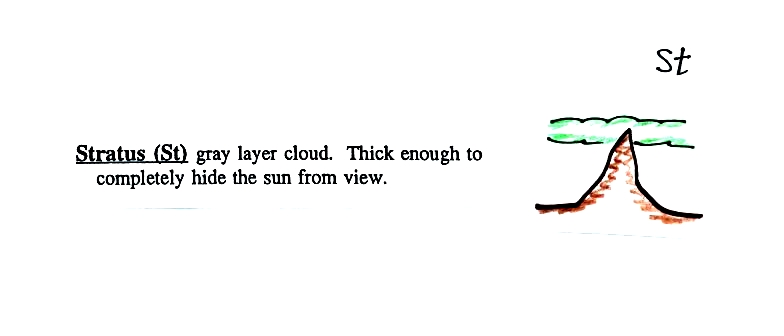

No pictures of stratus clouds were shown in class.

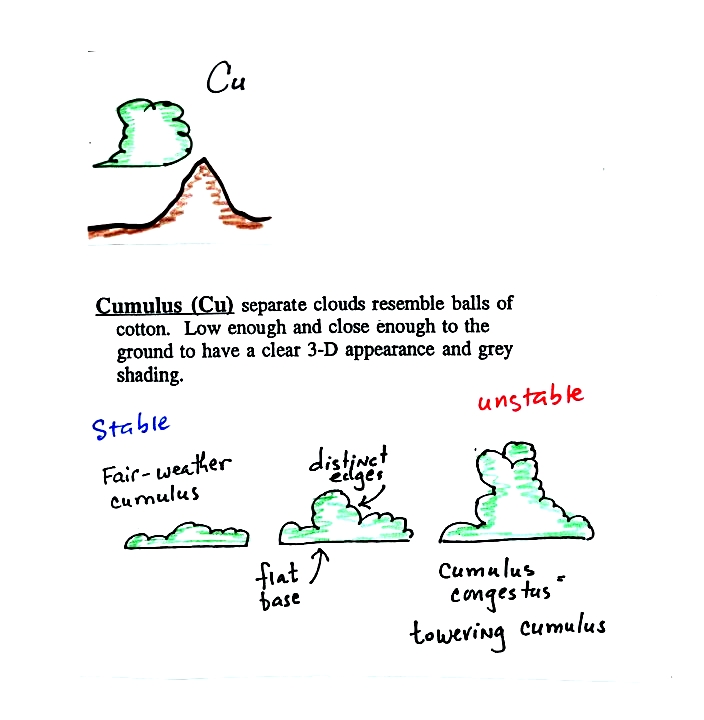

Cumulus clouds come with different degrees of vertical

development. The fair weather cumulus clouds don't grow much

vertically at all. A cumulus congestus cloud is an intermediate

stage between fair weather cumulus and a thunderstorm.

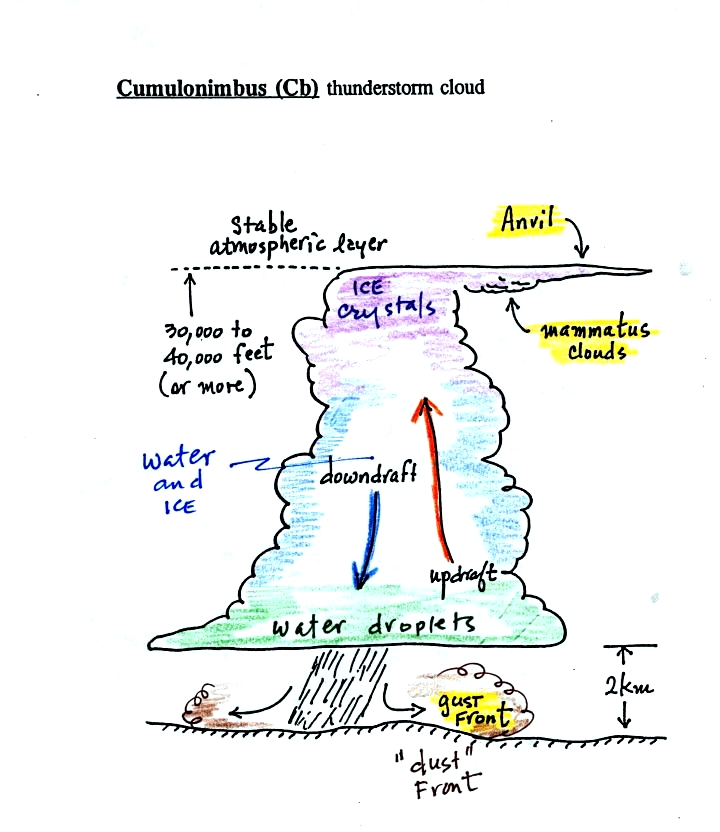

There are lots of distinctive features on cumulonimbus

clouds including the flat anvil top and the lumpy mammatus clouds

sometimes found on the underside of the anvil. Cold dense

downdraft winds hit the ground below a thunderstorm and spread out

horizontally underneath the cloud. The leading edge of these

winds produces a gust front. Winds at the ground below a

thunderstorm can exceed 100 MPH, stronger than many tornadoes.

The top of a thunderstorm is cold enough that it will be composed of

just ice crystals. The bottom is composed of water

droplets. In the middle of the cloud both water

droplets and ice crystals exist together at temperatures below freezing

(the water droplets have a hard time freezing). Water and ice can

also be found together in nimbostratus clouds. We will see that

this mixed phase region of the cloud is important for precipitation

formation. It is also where the electricity that produces

lightning is generated.

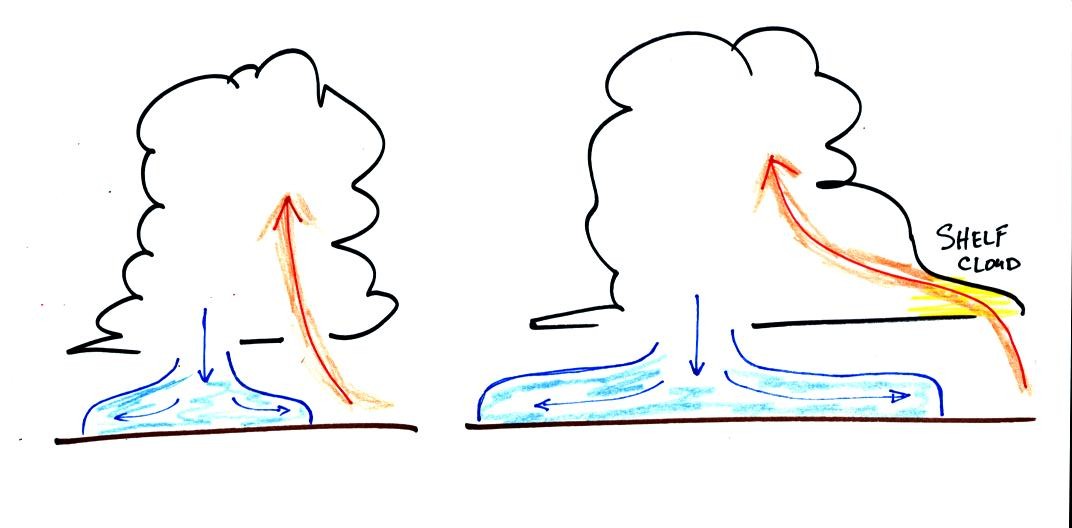

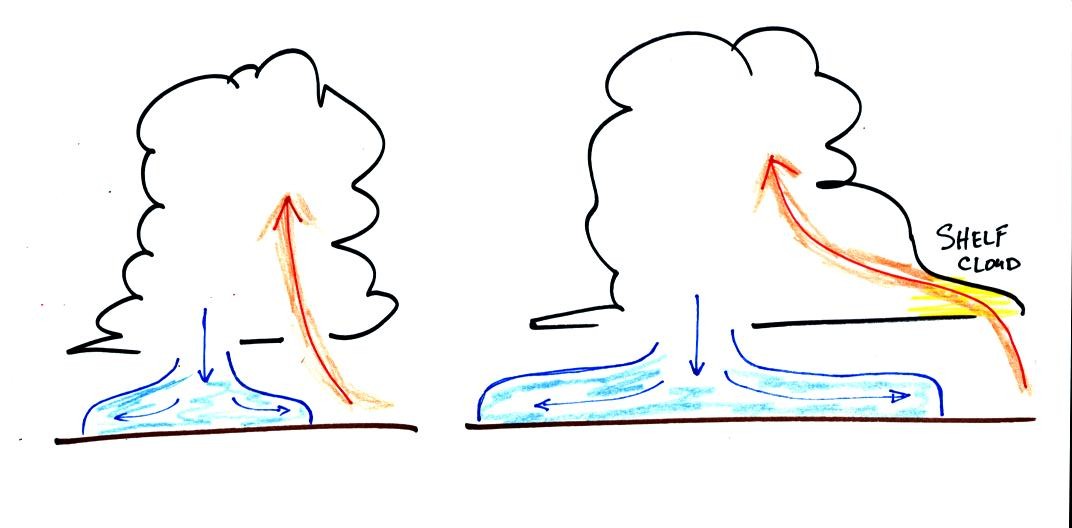

Here's one final feature to look for at the bottom of a

thunderstorm.

Cold air spilling out of the base of a thunderstorm is just

beginning

to move outward from the bottom center of the storm in the picture at

left. In the picture at right the cold air has moved further

outward and has begun to get in the way of the updraft. The

updraft is forced to rise earlier and a little ways away from the

center of the thunderstorm. Note how this rising air has formed

an extra lip of cloud. This is called a shelf cloud. You'll

find a good photograph of a shelf cloud in Fig. 10.7 in the text.

Here's our completed cloud chart with sketches of each of the

cloud types (cloud name abbreviations are shown here, rather than the

full cloud name).

We finished the class with a

quick look at the time and effort required to create a

thunderstorm. The following detailed discussion was intended to

prepare you and allow you to better appreciate a time lapse video movie

of a thunderstorm developing over the Catalina mountains. I don't

expect you to remember all of the details given below. The

figures below are more carefully versions of what was done in class.

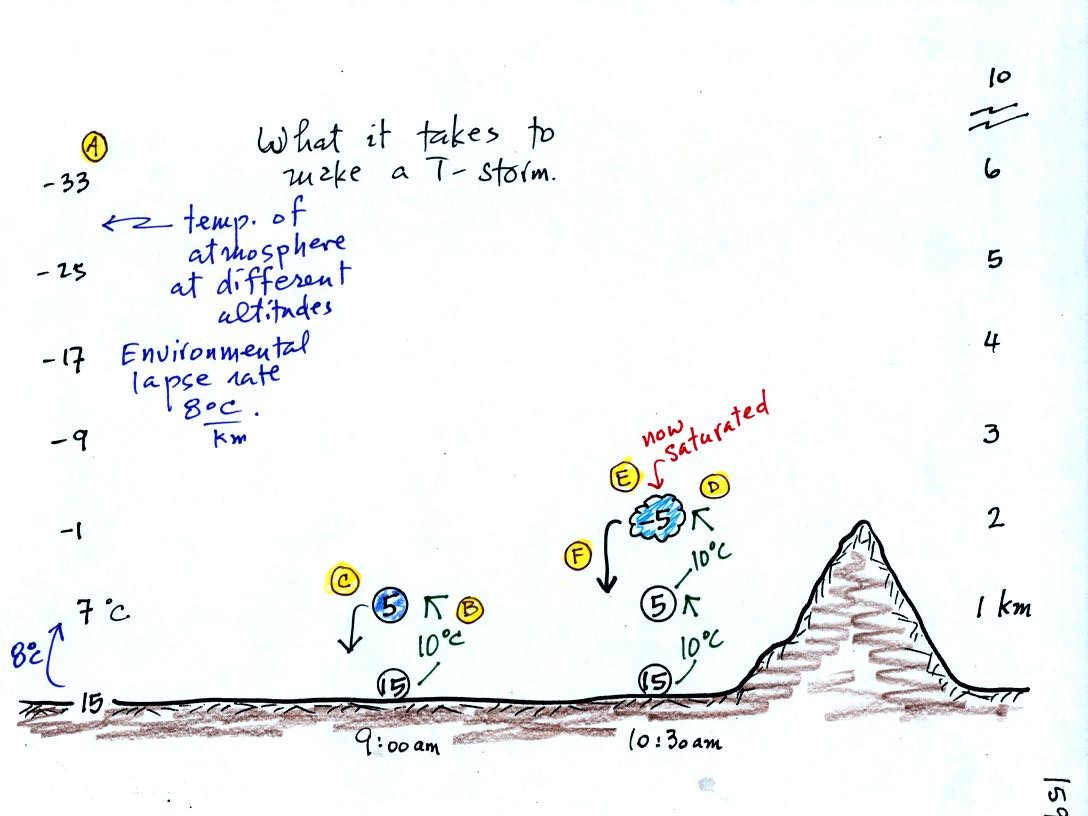

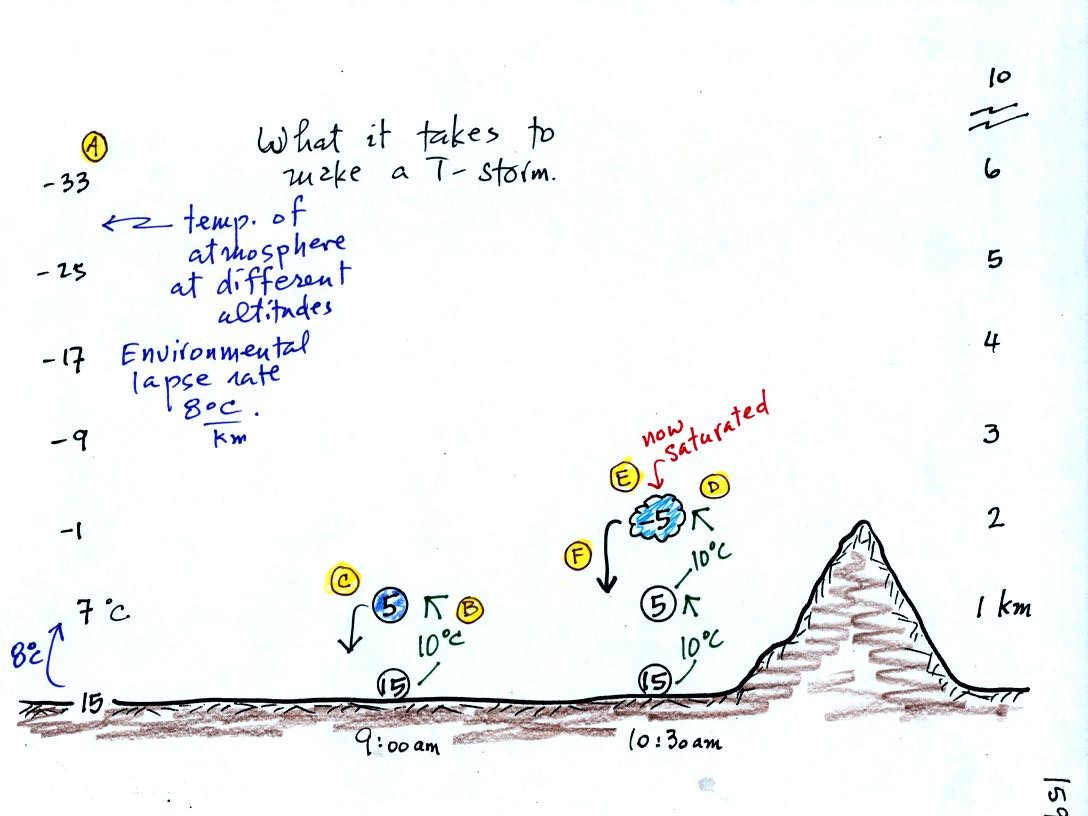

Refer back and forth between the lettered points in the

figure

above and the commentary below.

The numbers in Column A

show the temperature of the air in the atmosphere at various altitudes

above the ground (note the altitude scale on the right edge of the

figure). On this particular day the air temperature was

decreasing at a rate of 8 C per kilometer. This rate of decrease

is referred to as the environmental lapse rate. Temperature could

decrease more quickly than shown here or less rapidly.

Temperature in the atmosphere can even increase with increasing

altitude

(a temperature inversion).

At Point B, some of

the surface air is put into an imaginary container, a parcel.

Then a meterological process of some kind lifts the air to 1 km

altitude (in Arizona in the summer, sunlight heats the ground and air

in contact with the ground, the warm air becomes bouyant). The

rising air will expand and cool as it is

rising. Unsaturated (RH<100%) air cools at a rate of 10 C per

kilometer. So the 15 C surface air will have a temperature of 5 C

once it arrives at 1 km altitude.

At Point C note that

the air inside the parcel is slightly colder than the air outside (5 C

inside versus 7 C outside). The air inside the parcel will be

denser than the air outside and, if released, the parcel will sink back

to the

ground.

By 10:30 am the parcel is being lifted to 2 km as shown at Point D. It is still

cooling 10 C for every kilometer of altitude gain. At 2 km, at Point E the

air has cooled to its dew point temperature and a cloud has

formed. Notice at Point

F, the air in the parcel or in the cloud (-5 C) is still colder

and denser than the surrounding air (-1 C), so the air will sink back

to the ground and the cloud will disappear. Still no thunderstorm

at this point.

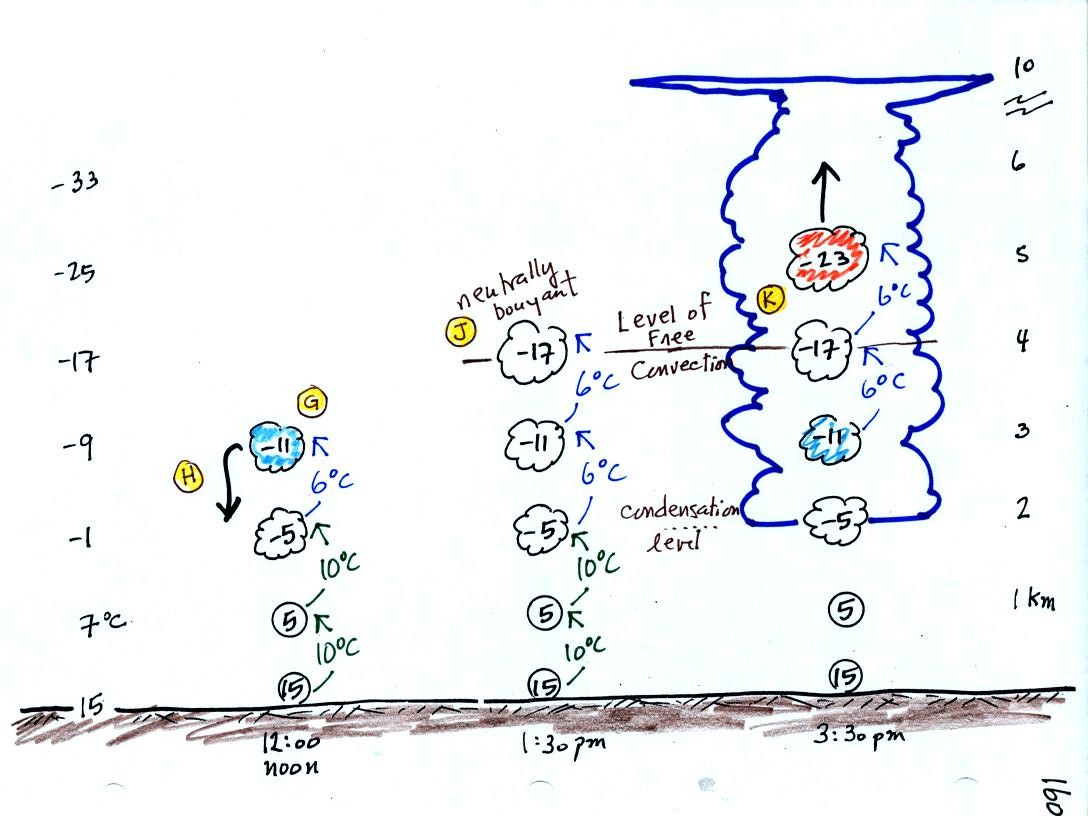

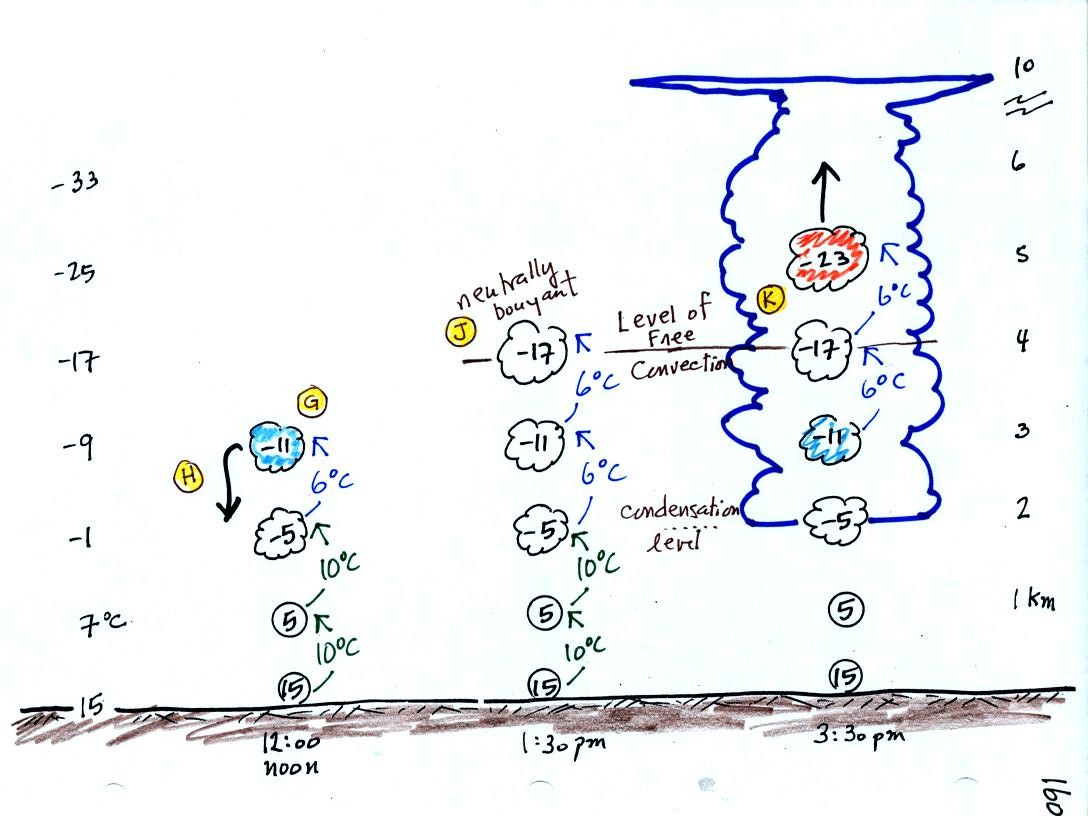

At noon, the air is lifted to 3 km. Because the

air

became saturated at 2 km, it will cool at a different rate

between 2 and

3 km altitude. It cools at a rate of 6 C/km instead of 10

C/km. The saturated air cools more slowly because release of

latent heat

during condensation offsets some of the cooling due to

expansion. The air that arrives at 3km, Point H, is again still

colder than the

surrounding air and will sink back down to the surface.

By 1:30 pm the air is getting high enough that it becomes neutrally

bouyant, it has the same temperature and density as the air around it

(-17 C inside and -17 C outside). This is called the level of

free convection, Point J in the figure.

If you can, somehow or another, lift air above the level of free

convection it will find itself warmer and less dense than the

surrounding air as shown at Point K and will float upward to the top of

the troposphere on its own. This is really the

beginning of a thunderstorm. The thunderstorm will grow upward

until it reaches very stable air at the bottom of the stratosphere.