An interesting survey of the costs of various

types of lightning damage was on a handout distributed in class.

This came from the first 3 or 4 pages in Chapter 2 of Uman's The Art

and Science of Lightning Protection. Here are a few of the

figures on the handout:

The 1977 power blackout in

Estimates of the costs of lightning damage to

insurance companies range from 1/3 to $1

billion. In total about 5% of insurance claims involve lightning

(50%

in

30,000 house fires caused every year by lightning. About half of the 20,000 wildfires every year are caused by lightning. The cost of fighting wildfires was about $1.5 billion in 2006 (a record year).

Lightning damage to commercial airlines costs

~$2 billion per year. Damage to military aircraft is comparable.

Lightning causes damage to perhaps 100,000 computers/year.

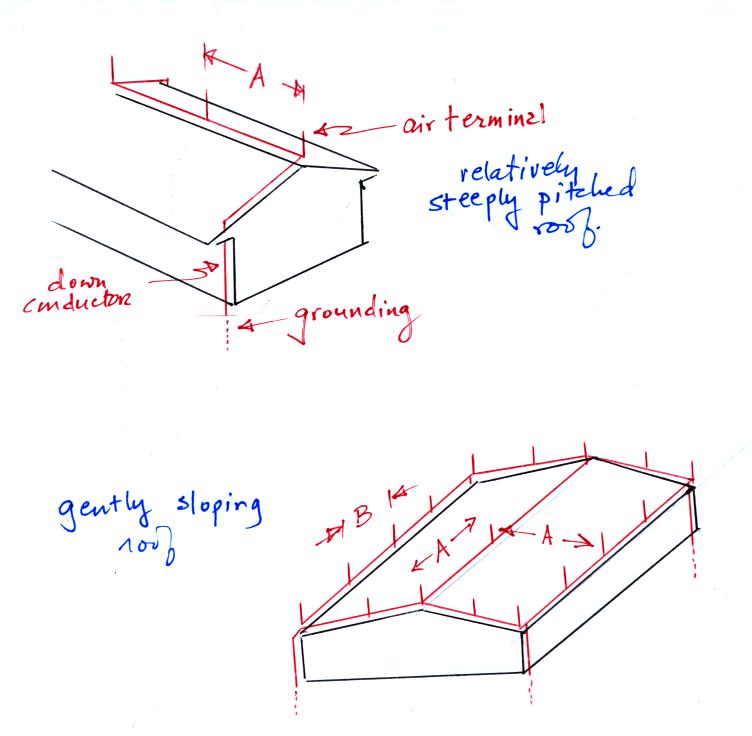

Lightning protection for a house or

building usually consists of 3 components:

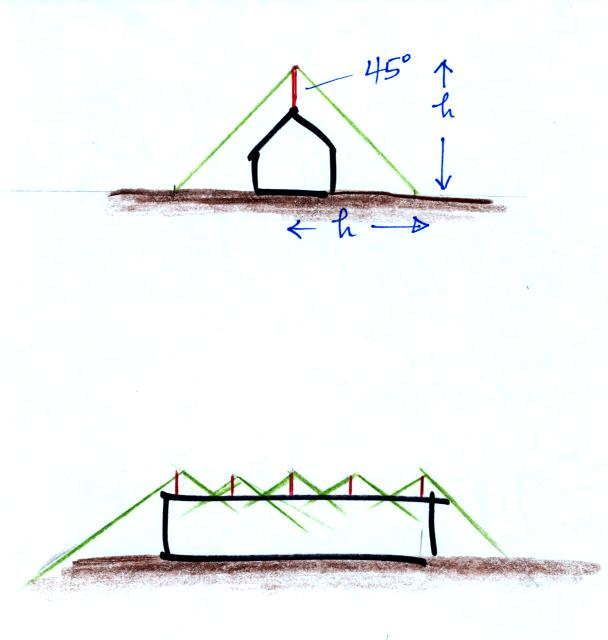

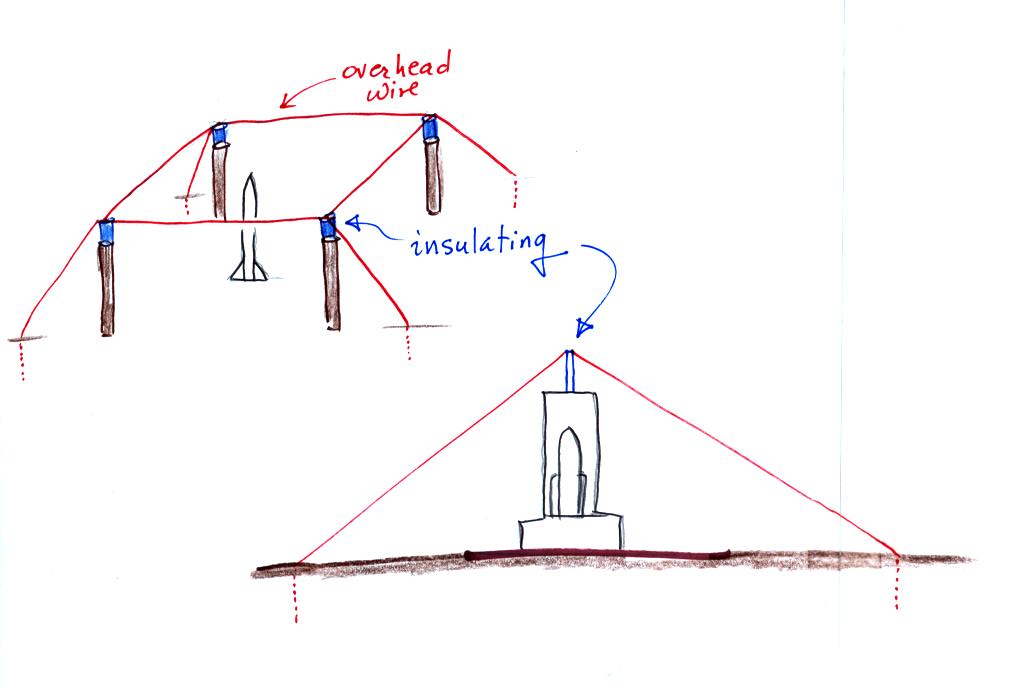

For structures less than 50 feet tall

a lightning rod provides a 45o

or 60o cone of

protection. The 45o

A larger structure can be protected with

multiple rods with overlapping zones of protection.

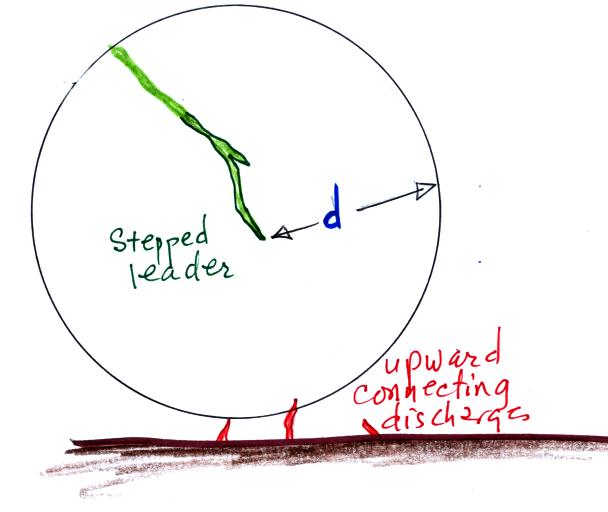

A different approach is used for larger structures. We need

to recall that the striking distance, d, is the distance between

the leader tip and the moment upper connecting discharges are initiated

at the ground. The leader can potentially strike anything withing

a d of the leader tip.

In the rolling sphere method, you imagine rolling a sphere of radius d

(d is the striking distance) over the building being evaluated for

lightning vulnerability. Parts

of the building touched by the sphere are at risk. Portions that

aren't touched are safe.

The height of the building at

left is less than or equal to d. The sides of the building aren't

touched by the sphere, the top is. Lightning protection would

need to be installed on the roof. The building at right is quite

a bit higher than d. Much of the sides as well as the roof can be

struck by lightning. Protection would need to be installed on the

top sides of the building and the roof. Fragments of building

materials knocked off the sides of buildings by lightning are

apparently a serious hazard to people on the street below.

The designers could make metal window shades and window frames part of

the lightning protection system by connecting them to the down

conductor.

Note the spacing of the air

terminals must be such that the rolling sphere doesn't touch the roof

in between adjacent lightning rods.

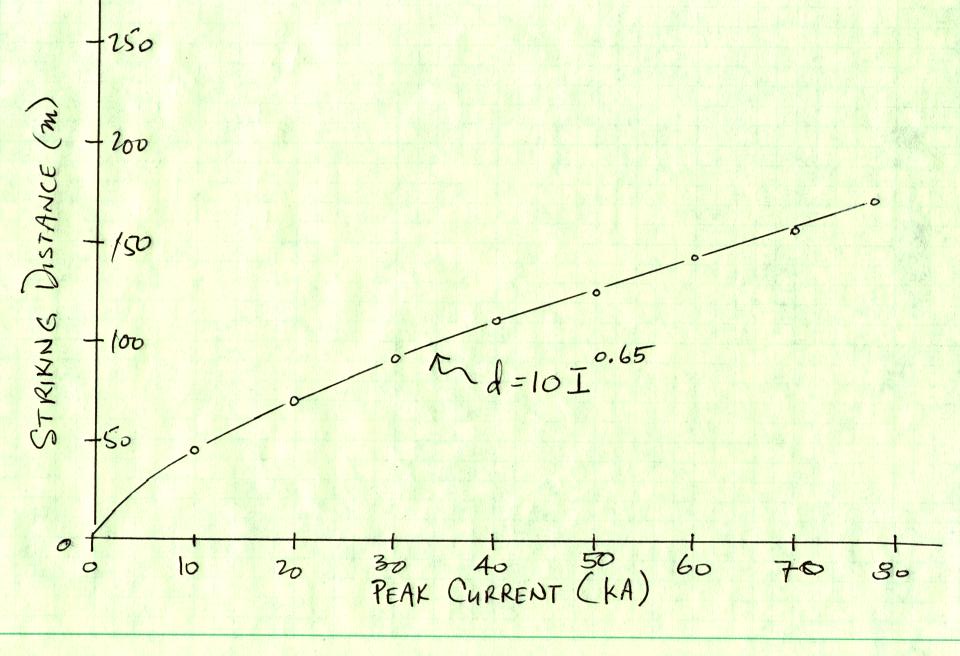

What value of d should be used? Researchers have tried to relate

the striking distance to the amplitude

of the peak return stroke that follows. Generally an expression

of the form

is used. A class handout

showed curves drawn using the most commonly assumed values for A and

b. I've one of the curves on that graph below

| protection level |

d |

minimum peak I |

% rs>Imin |

| I |

20 m |

3 kA |

99% |

| II |

30 |

5 |

97 |

| III |

45 |

10 |

91 |

| IV |

60 |

16 |

84 |

Protection of a

roof

A roof can be protected by multiple lightning

rods. An old question whether pointed rods or blunt rods

work

best. Some recent research (two articles by Moore et al, 2000 in

the class articles folder) suggest that the blunt rods might be more

effective. The NFPA allows either type to be used. Rods

should be at least 10 inches tall.

So called "unconventional" rods that use radioactivity or high voltage

to try to initiate an "earlier" upward connecting discharge are

generally not thought to be any more effective than conventional

"Franklin" rods.

A wire mesh covering

the roof of a building or vulnerable installation

on the ground can be used instead of lightning rods. A wire mesh

covered the administration trailer at the rocket triggered lightning

site in Florida for example.

The following table gives recommendations for the spacing of the wires

in a wire mesh (based on Table 4.2 in Uman's "The Art and Science of

Lightning Protection")

| protection level |

d |

mesh spacing |

| I |

20 m |

5 m x 5 m |

| II |

30 |

10 x 10 |

| III |

45 |

15 x 15 |

| IV |

60 |

20 x 20 |

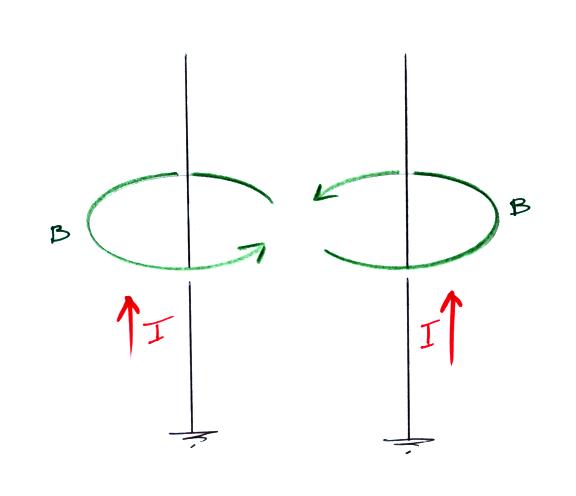

Air terminals should be connected to as many

down conductors as possible. Lightning rods on a house should be

connected to at least two down conductors (at opposite corners of the

house for example).

There are several reasons for this:

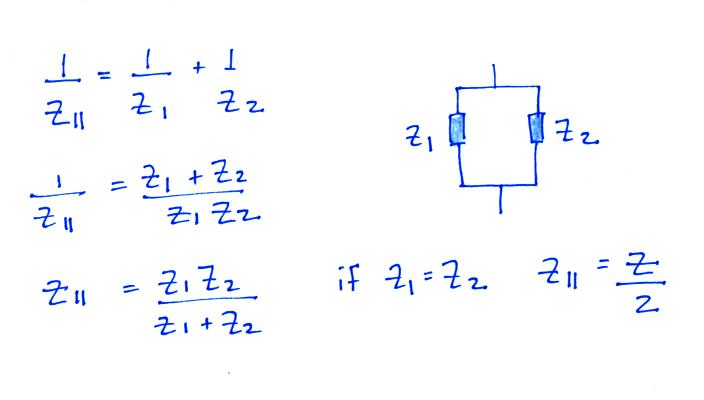

(i) reduce impedance (connecting inductors or

resistors in parallel reduces the combined impedance)

(ii) reduce B fields inside the structure

(the B fields from two down conductors positioned on opposite sides of

a building will point in opposite directions in the interior of the

building)

The recommended minimum crossectional area is about 50 mm2 for copper (that correcponds to a radius of 4 mm, a diameter of 8 mm or roughly 1/3 inch)

3 x 106 V/m is need to breakdown air at sea level

500 kV/m is the average field needed for propagation of negative

polarity leaders

300 kV/m is the average field needed for positive leader propagation.

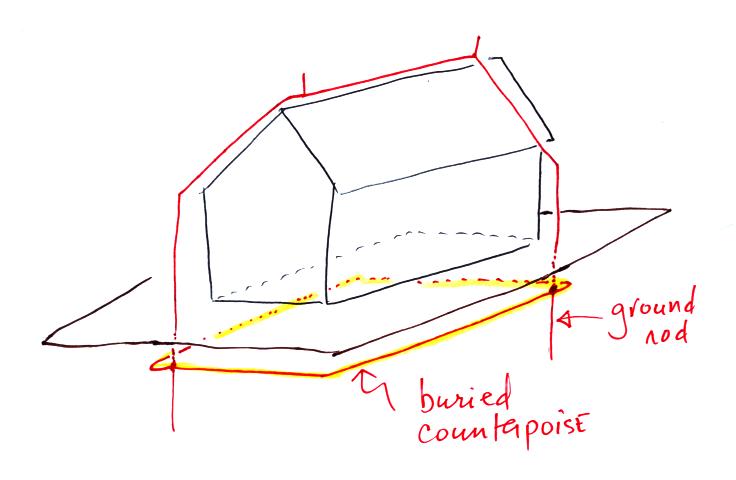

A couple of sections of copper clad grounding rods were shown in

class. Grounding rods should be at least 8 feet long and the

bottom end should be at least 10 feet deep.

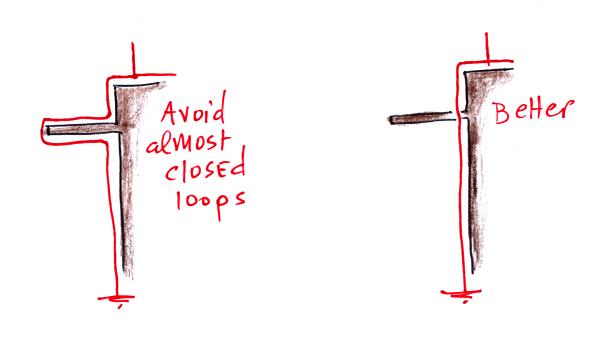

Grounding can be improved by connecting grounding rods to a

counterpoise, a loop of grounding wire that encircles the

structure. This reduces potential differences inside the loop.

A handout had a table of resistivities of various materials (Table

5.1 in Uman's "The Art and Science of Lightning Protection").

material

resistiviy in ohm-meters

ocean water

0.1 - 0.5

ground, well & spring

water

10 - 150

lake & river water

100 - 400

rain water

800 - 1300

commercial distilled water

1000 - 4000

chemically clean water

250000

clay

25 - 70

sandy clay

40 - 300

peat, marsh &

cultivated soil

50 - 250

sand

1000 -3000

moraine

1000 - 10000

ose (calcereous remains)

3000 - 30000

| rod length |

resisitivity 100 ohm-meter |

resistivity 1000 ohm-meter |

| 3 m |

35 ohms |

350 ohms |

| 6 |

22 |

220 |

| 9 |

15 |

150 |

| wire length |

resisitivity 100 ohm-meter |

resistivity 1000 ohm-meter |

| 50 m |

4.0 ohms |

40 ohms |

| 100 |

2.6 |

26 |

| 200 |

1.4 |

14 |