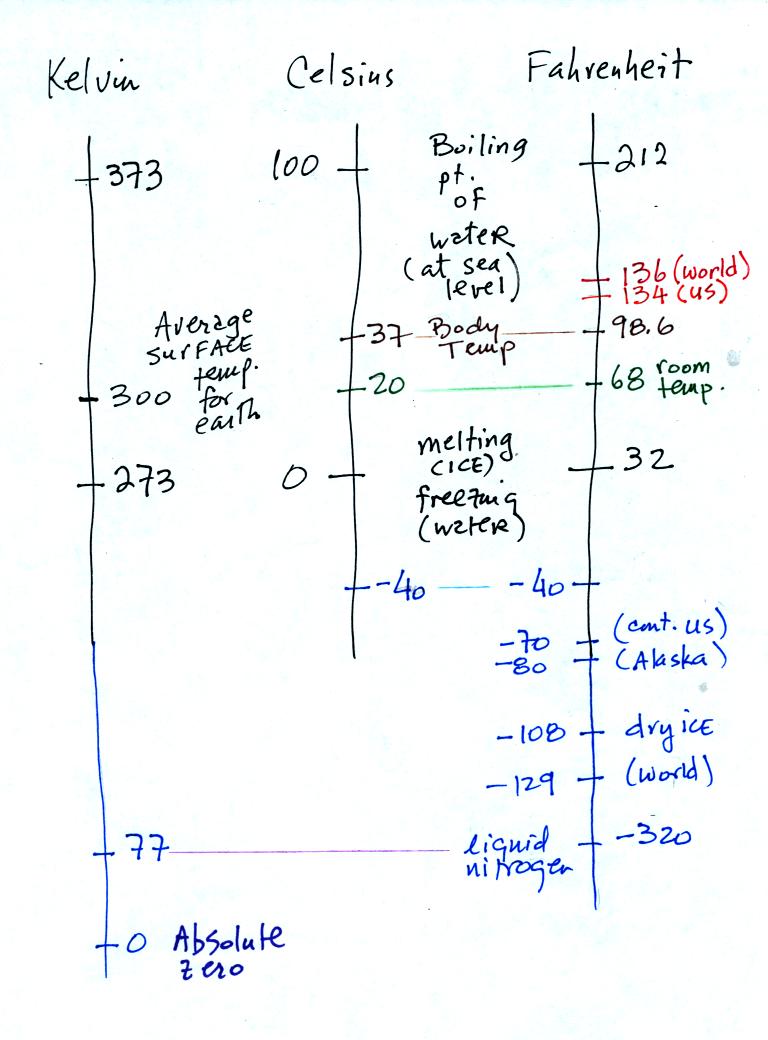

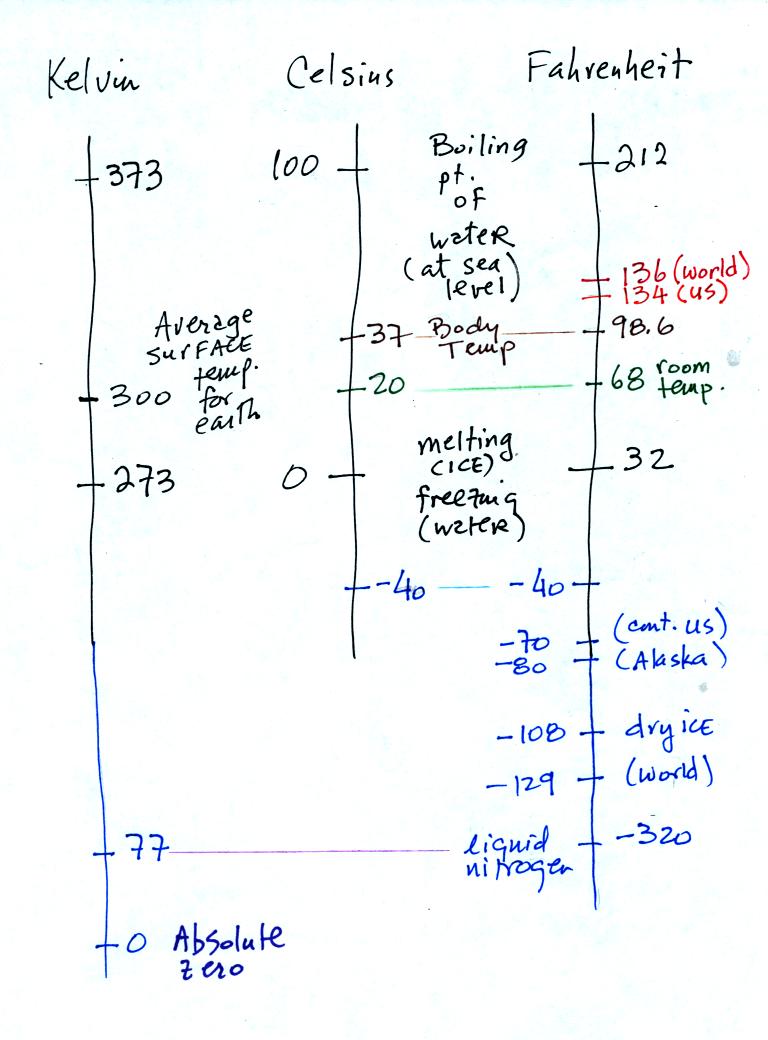

You certainly don't need to try to

remember all these

numbers. The world high temperature record was set in Libya, the

US

record in

Death Valley. The continental US cold temperature record of -70 F

was set in Montana and the -80 F value in Alaska. The world

record -129 F was measured at Vostok station in Antarctica. This

unusually cold reading was the result of three factors: high latitude,

high altitude, and location in the middle of land rather than being

near or

surrounded by ocean (water moderates climate).

Liquid

nitrogen is cold but it is still quite a bit warmer than absolute

zero. Liquid helium gets within a few degrees of absolute zero,

but it's expensive and there's only a limited amount of helium

available. So I would feel guilty bringing some to class.

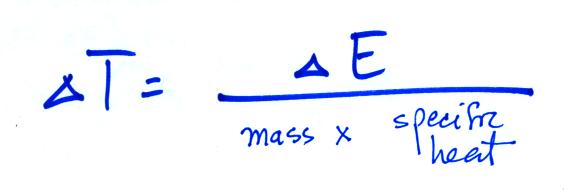

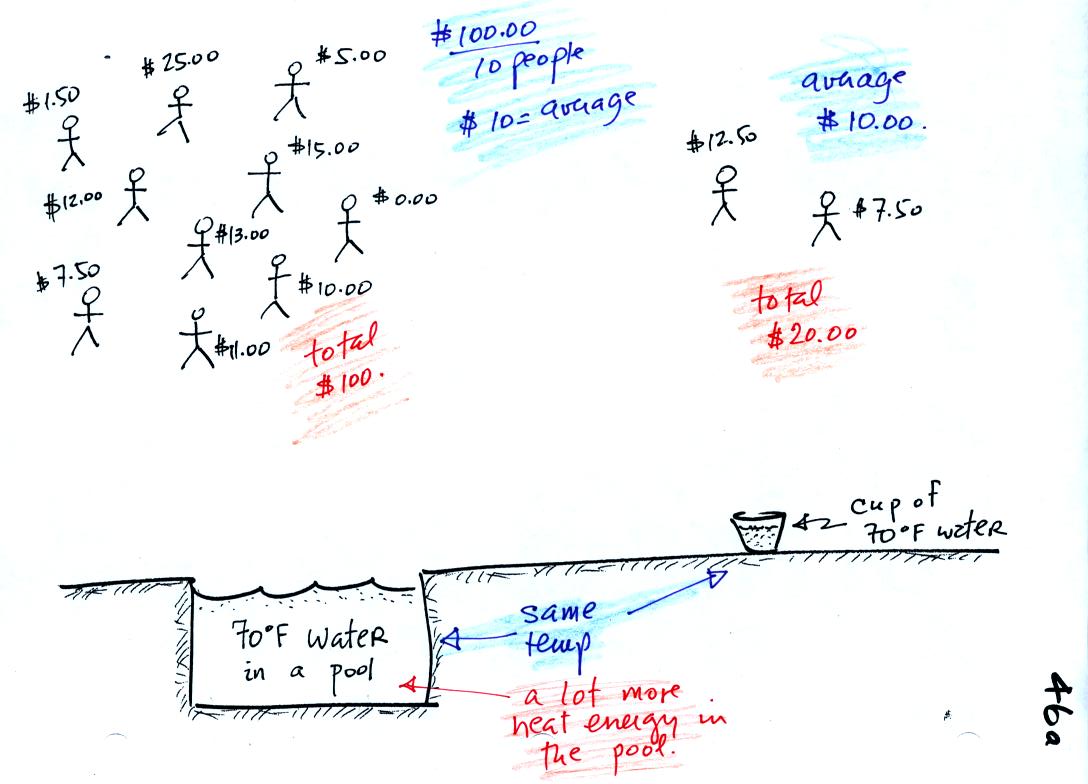

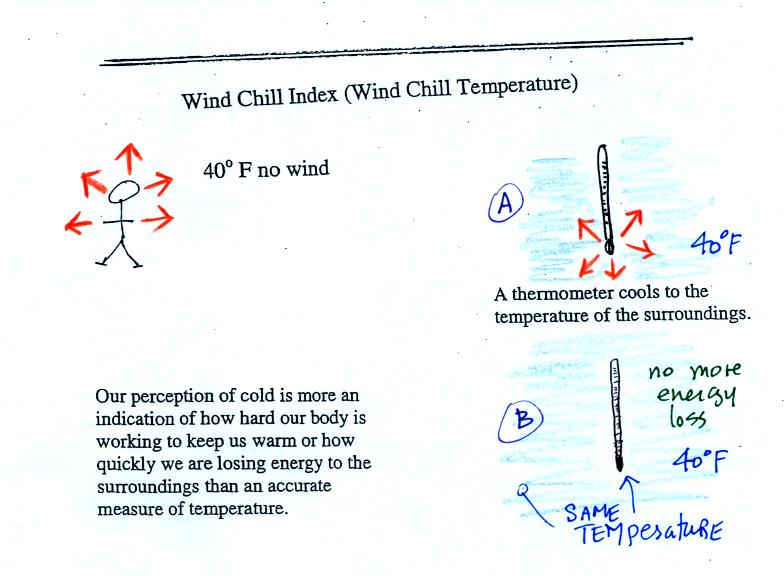

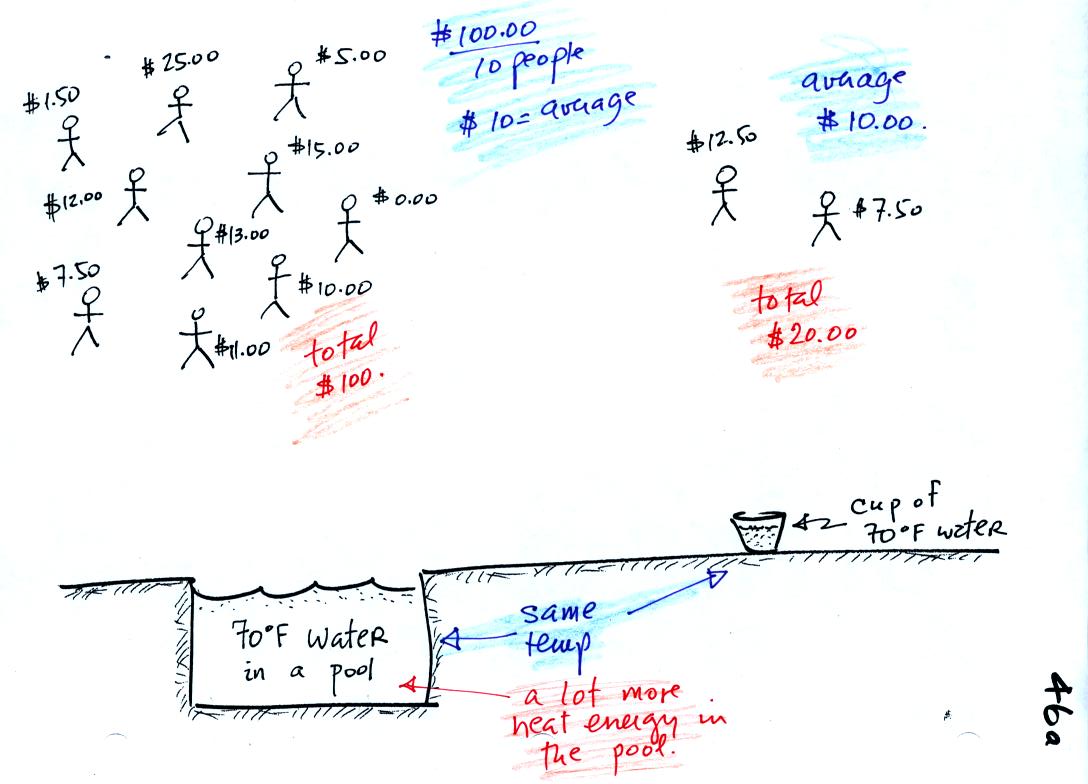

This next figure might make clearer the difference between

temperature (average kinetic energy) and heat (total kinetic energy).

A cup of water and a pool of water

both have the same

temperature. The average kinetic energy of the water molecules in

the pool and in the cup are the same. There are a lot more

molecules in the pool than in the cup. So if you add together all

the kinetic

energies of all the molecules in the pool you are going to get a much

bigger number than if you sum the kinetic energies of the molecules in

the cup. There is

a lot more stored energy in the pool than in the cup. It would be

a lot harder to cool (or warm) all the water in the pool than it would

be the cup.

In the same way the two groups of people shown have the same

average

amount

of money per person (that's analogous to temperature). The $100

held by the larger group at the

left is

greater than the $20 total possessed by the smaller group of people on

the right (total amount of money is analogous to heat).

Conduction

is the first of four energy transport processes

that we

will cover (and the least important transport process in the

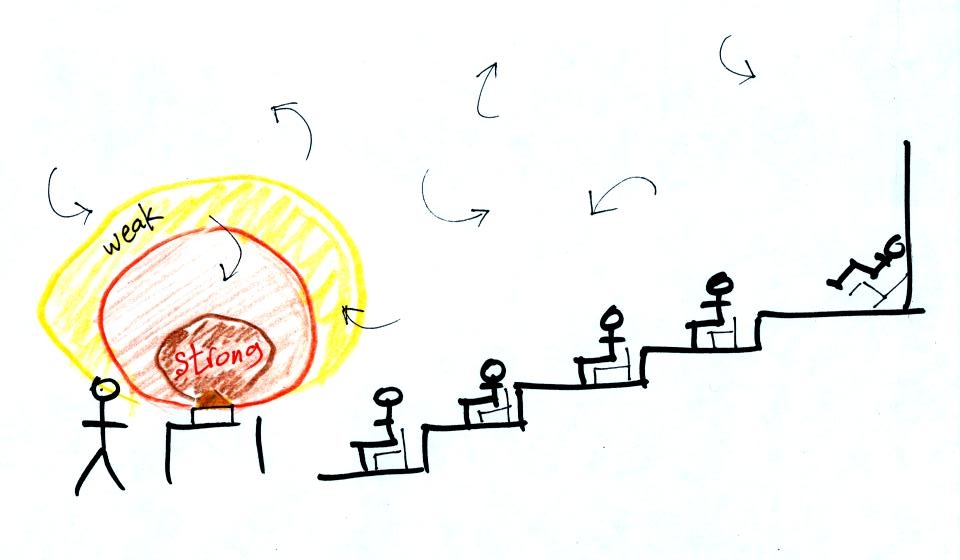

atmosphere). The figure below illustrates this process. A

hot object is stuck in the middle of some air.

In the top picture some of the

atoms or molecules near the

hot object have collided with the object and picked up energy from the

object. This is reflected by the increased speed

of motion or increased kinetic energy of these molecules or

atoms (these guys are colored pink).

In the middle picture the

initial bunch of

energetic molecules have

collided with some of their neighbors and shared energy with

them (these are orange). The neighbor molecules have gained

energy though they don't

have as much energy as the molecules next to the hot object.

In

the third picture molecules further out have now (the yellow ones)

gained

some energy. The random motions and collisions

between molecules

is carrying energy from the hot object out into the colder material.

Conduction transports energy from hot to cold. The

rate

of

energy

transport depends first on

the temperature

gradient of temperature difference. If the object in the picture

had been warm rather

than hot, less energy would flow or energy would flow at a slower into

the surrounding air.

The rate of

energy transport also depends on the material transporting energy (air

in the example

above). Thermal

conductivities of some common materials are listed. Air is a very

poor conductor of energy. Air is generally regarded as an

insulator. Water is a little bit better conductor. Metals

are generally very good conductors (cooking pans are often made of

stainless steel but have aluminum or copper bottoms to evenly spread

out heat when placed on a stove). Diamond has a very high

thermal conductivity. Diamonds are sometimes called "ice."

They feel cold when you touch them. The cold feeling is due to

the fact that they conduct energy very quickly away from your warm

fingers when you touch them.

Transport of energy by conduction is similar to the

transport of a strong smell throughout a classroom by diffusion.

Small eddies of wind in the classroom blow in random directions and

move smells throughout the room.. For our demonstration we used

curry powder.

With time the smell should have

spread

throughout the room. It didn't seem to though. Next time

maybe I'll trying frying some smelly fish of something like that.

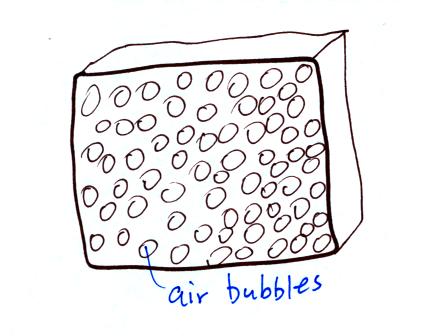

Because

air has such a low thermal conductivity it is often used as an

insulator. It is important, however, to keep the air trapped in

small pockets or small volumes so that it isn't able to move and

transport energy by convection (we'll look at convection

shortly). Here are some examples of

insulators that use air:

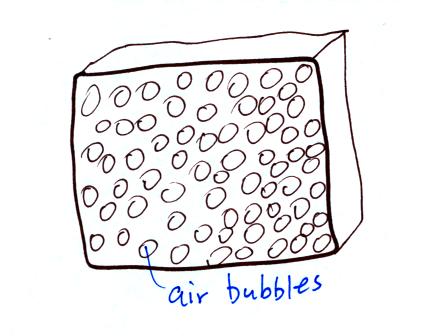

Foam is

filled with lots of small air bubbles, they're what provides the

insulation.

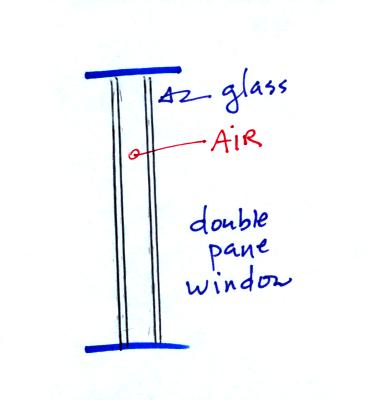

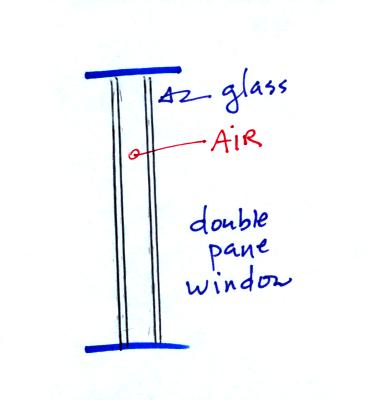

Thin

insulating layer of air in a double

pane window. I don't have double pane

windows in my house. As a matter of fact

I leave a window open so the cats can get in and

out of the house (that's not particularly energy

efficient). And the stray cats have found out about it and come

in to eat my cat's food (and pee on the furniture). Maybe

sprinkling curry powder on the carpet will keep the stray cats out.

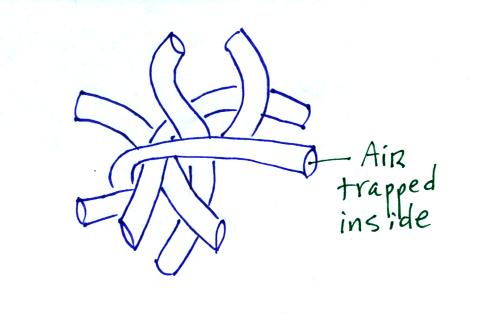

Here's another example

that I didn't

mention in class. Hollow fibers

(Hollofil) filled with air used in

sleeping

bags and

winter coats. Goose feathers

(goosedown) work in a similar way.

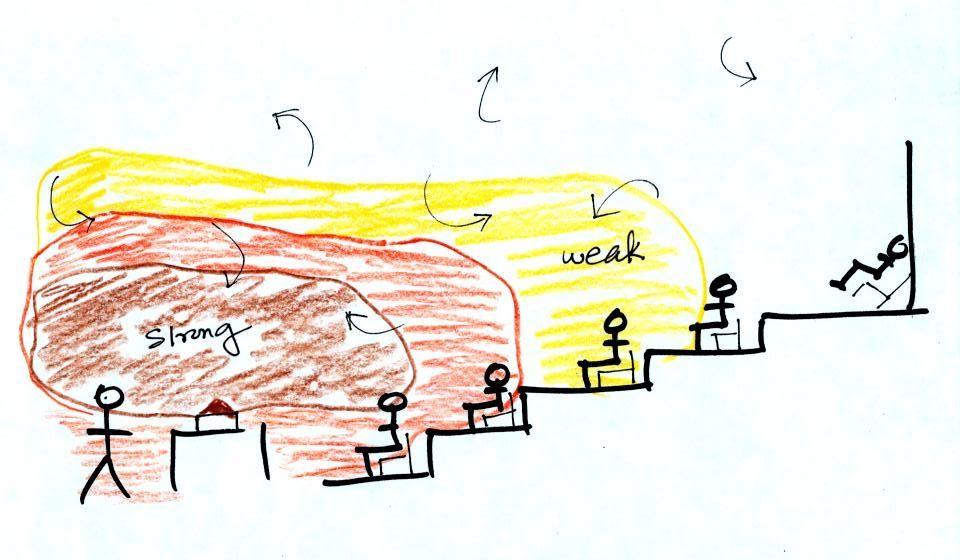

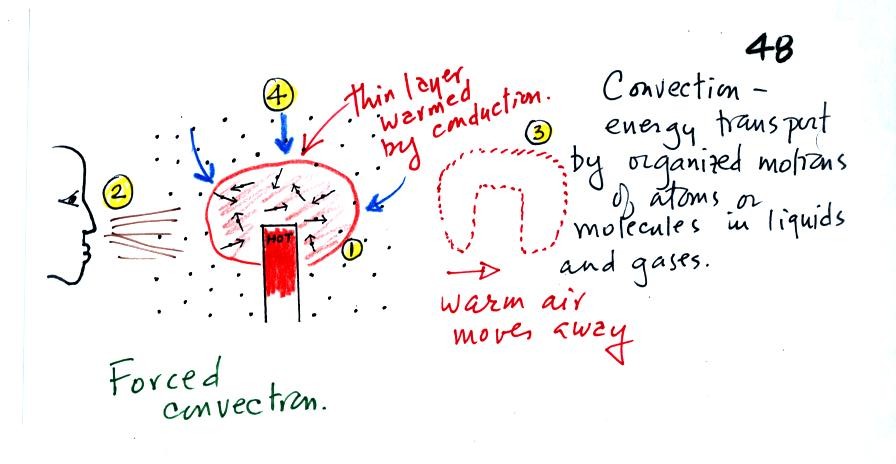

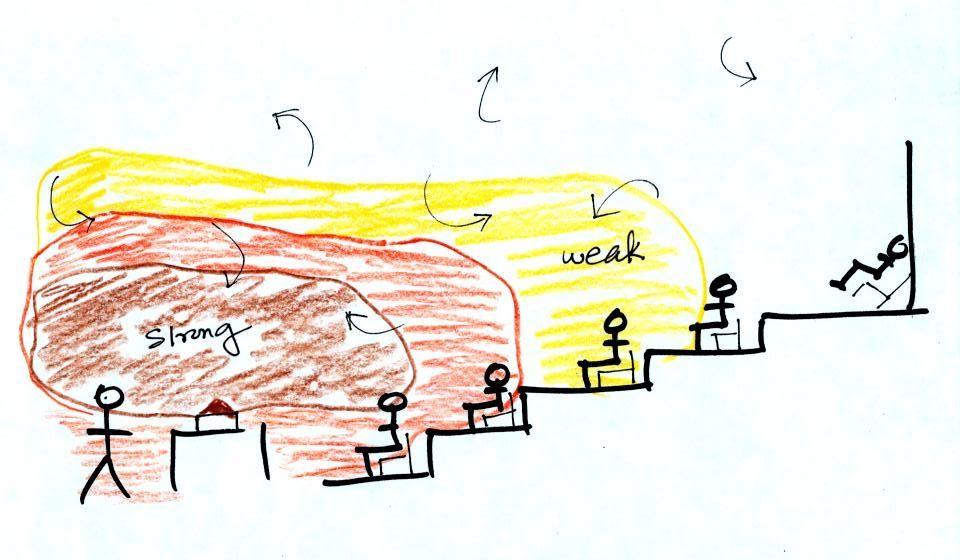

Convection

was the next energy transport process we had a look at. Rather

than moving about randomly, the atoms or molecules move together as a

group (organized motion). Convection works in liquids and gases

but not

solids (the atoms or molecules in a solid can't move freely).

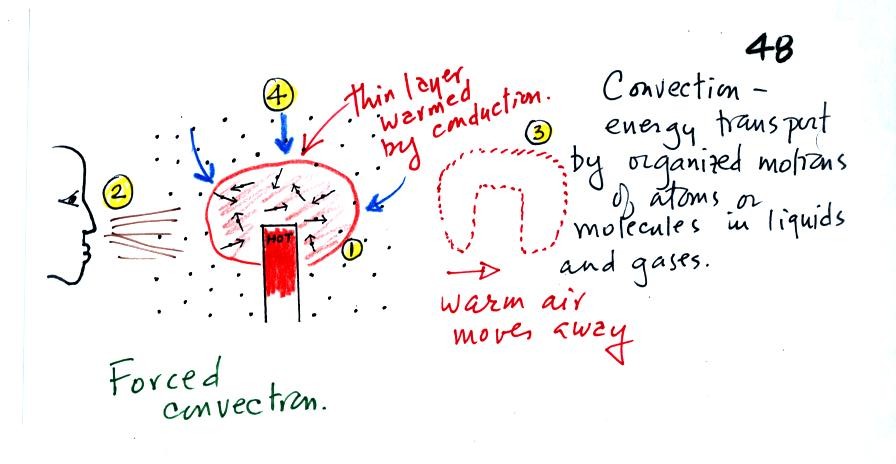

At Point 1 in the picture above a

thin layer of air

surrounding a hot object has

been

heated by conduction. Then at Point 2 a person (yes, that is a drawing

of a

person's head) is blowing the blob of warm air

off to the right. The warm air molecules are moving away at Point

3 from the

hot object together as a group (that's the organized part of the

motion). At Point 4 cooler air moves in and surrounds the hot

object and the whole process can repeat itself.

This is forced

convection. If you have a hot object in your hand you could just

hold onto it and let it cool by conduction. That might take a

while because air is a poor conductor. Or you could blow on the

hot object and force it to cool more quickly. I put a

small fan behind the curry powder to try to help spread the

smell faster and further out into the classroom.

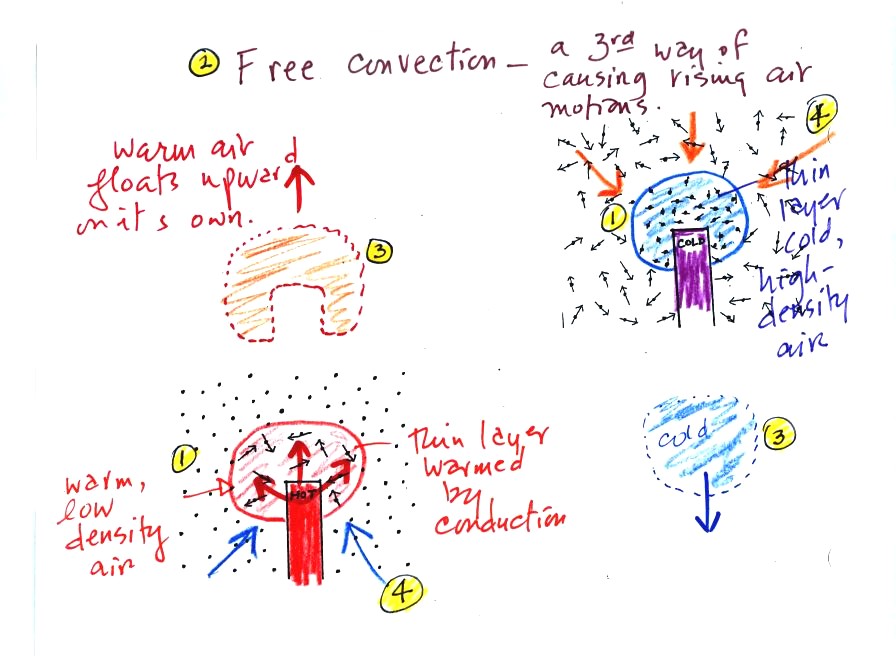

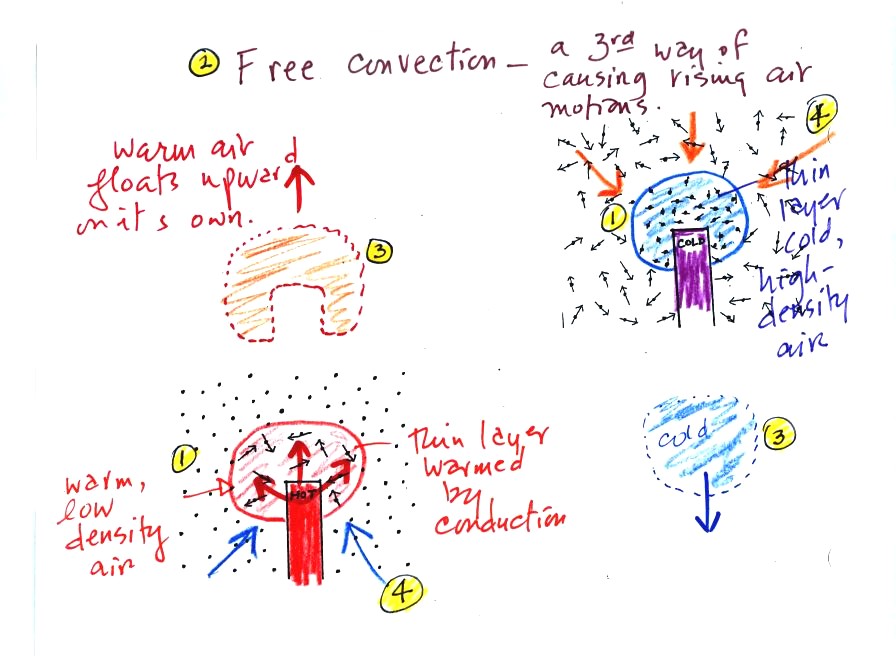

And actually you don't need to force convection, it will often happen

on its own.

A thin layer of air at Point 1 in

the figure above (lower

left) is

heated by conduction. Then because hot air is also

low density air, it actually isn't necessary to blow on the hot object,

the

warm air will rise by itself (Point 3). Energy is being

transported away

from the hot object into the cooler surrounding air. This is

called free convection. Cooler air moves in to take the place of

the rising air at Point 4 and the cycle repeats itself.

The example at upper right is also

free convection. Room temperature air in contact with a cold

object loses energy and becomes cold high density air. The

sinking

air motions that would be found around a cold object have the effect of

transporting energy from the room temperature surroundings to the

colder object.

In both examples of free convection, energy is being transported

from

hot toward cold.

Now some

what I think are some fairly practical applications of what we have

learned about conductive and

convective energy transport. Energy transport really does show up

in a lot more everyday real life situations than you might expect.

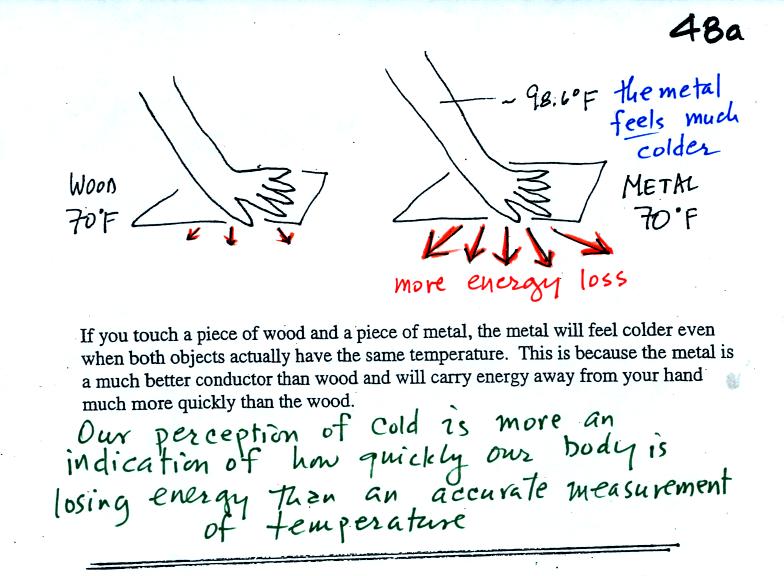

Note first of all there is a temperature difference between

your hand and a 70 F object. Energy will flow from your warm

hand to the colder object. Metals are better conductors than

wood. If you touch a

piece of

70 F metal it will feel much colder than a piece of 70 F wood, even

though they both have the same temperature. A

piece

of 70 F diamond would feel even colder because it is an even better

conductor

than metal.

Something that feels cold may not be as

cold as it seems. Our perception of cold is more an

indication of how

quickly our hand is losing energy than a reliable measurement of

temperature.

Here's a similar situation.

It's pleasant

standing outside on a nice day in 70 F air. But if

you jump into 70 F pool water you

will

feel cold, at least until you "get used" to the water temperature (your

body might reduce blood flow to your extremeties and skin to try to

reduce energy loss).

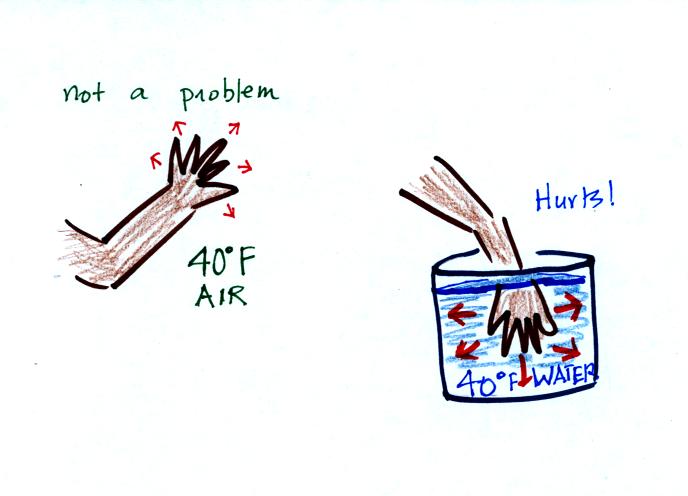

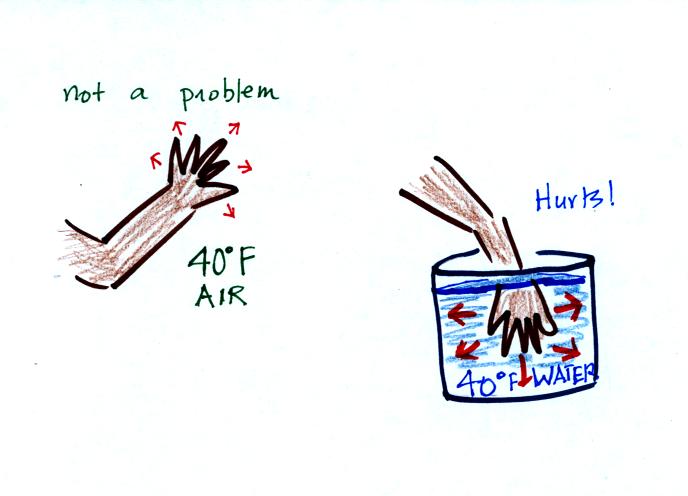

Air is a poor conductor. If you go out in

40 F

weather you will feel colder largely because there is a larger

temperature difference between you and your surroundings (and

temperature difference is one of the factors that affect rate of energy

transport by conduction).

If you stick your hand

into a bucket of 40 F water (I probably shouldn't, but I will suggest

you try this), it will feel very

cold (your hand will

actually soon begin to hurt). Water is a much better conductor

than air. Energy flows much more rapidly from your hand into the

cold water. Have some warm water nearby to warm your cold hand

back up.

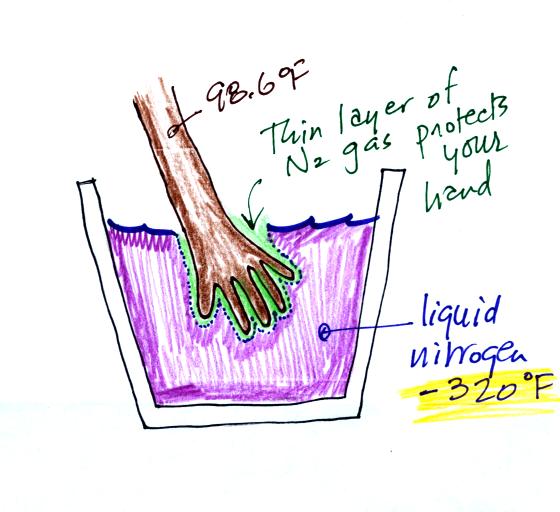

You can safely stick your

hand in liquid nitrogen for a fraction of a second. It doesn't

feel particularly cold and doesn't feel wet. Some of the liquid

nitrogen quickly evaporates and surrounds your hand with a layer of

nitrogen

gas. This gas is a poor conductor and insulates your

hand from the cold for a very short time (the gas is a poor conductor

but a

conductor nonetheless; if you leave your hand in the liquid nitrogen

for very long it will freeze and your hand would need to be amputated).

Our

perception of cold is a better indicator of how quickly our body is

losing energy rather than an accurate measurement of temperature.

This basic knowledge puts us in a perfect position to understand the

concept of wind

chill temperature.

Your body works hard to keep its core temperature around

98.6 F. If you go outside on a 40 F day (calm winds)

you will

feel

cool; your

body is losing energy to the colder surroundings (by conduction

mainly). Your body will be able to keep you warm for a little

while anyway (maybe indefinitely, I don't know). A thermometer

behaves differently, it is supposed to cool to the temperature of the

surroundings. Once it reaches 40 F it won't lose any additional

energy. If your body cools to 40 F you will probably die.

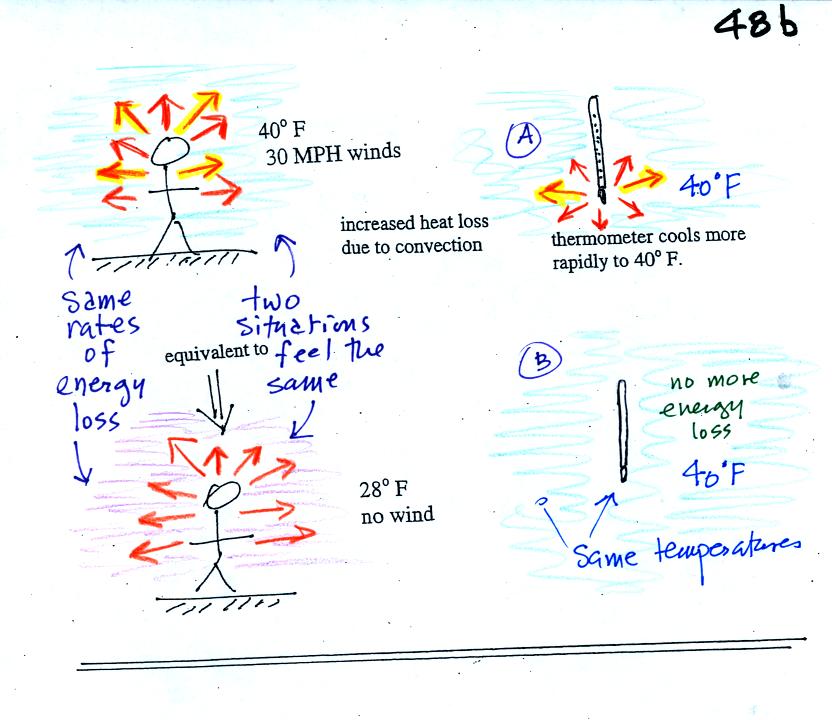

If you go outside on a 40 F day with 30 MPH winds your

body

will lose

energy at a more rapid rate (because convection together with

conduction are transporting energy away from your body). Note the

additional arrows drawn on the figures above indicating the greater

heat loss. This

higher rate of energy loss will make it feel colder

than a 40

F day

with calm winds.

Actually, in terms of the rate at which your

body loses energy, the windy 40 F day would feel the same as a 28

F day without any wind. Your body is losing energy at the same

rate in both

cases. The combination 40 F and 30 MPH winds results in a wind

chill temperature of 28 F.

The thermometer will again cool to the

temperature of its surroundings, it will just cool more quickly on a

windy day. Once the thermometer reaches 40 F there won't be any

additional energy flow. The

thermometer would measure 40 F on both the calm and the windy day.

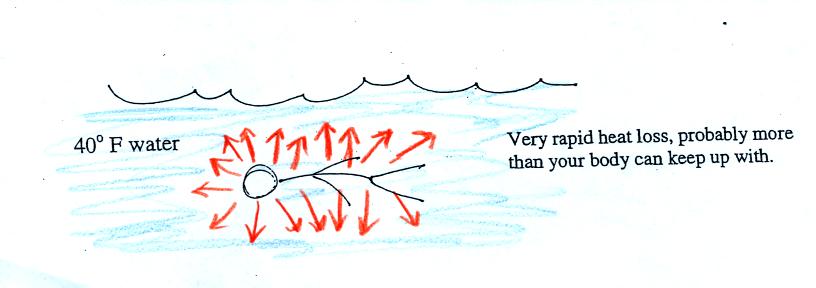

Standing outside on a 40 F day is not an immediate life

threatening

situation. Falling into 40 F water is.

Energy will be conducted away from your body more quickly

than

your

body can replace it. Your core body temperature will drop and

bring on hypothermia.

Be

sure

not

to

confuse

hypothermia

with

hyperthermia

which

can bring on

heatstroke and is a serious outdoors risk in S.

Arizona.